Author

Antoni Kępiński, MD, PhD, 1918–1972, Professor of Psychiatry, Head of the Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Academy of Medicine. Survivor of the Spanish concentration camp Miranda de Ebro.

“The concentration camp taught me one thing: to hate discipline and order.” These words were said by prof. Jan Miodoński, a survivor of Sachsenhausen concentration camp, during a discussion at a meeting of the Kraków branch of the Polish Medical Association. This may seem a rather strange statement for an elderly speaker to make in the last years of his life, in view of the key role discipline and order play in the life of the individual and of society.

The word “discipline” comes from the Latin discipulus (“disciple,” “student”) and discere (“to learn”). From the very moment of birth we are all “students” of our social environment, and all the time we are learning new kinds of “order” which integrate the ways in which we behave. This applies to all manner of disciplines: from the discipline of feeding, of the functions of excretion, locomotion and manipulation; through the discipline which involves the highest form of movement, namely verbal communication, thanks to which we acquire a ready-made system for the registration of our thoughts and feelings, and for the observation of the world that surrounds us; to all kinds of social, cognitive, aesthetic, and moral orders which we encounter and espouse during our lives.

We do not know the definition of life, but if we assume after the physicist Erwin Schrödinger that life is something that is in continuous defiance of entropy, i.e. matter tending to a state of chaotic molecular movement, then order becomes the most crucial attribute of life.

Continuously exchanging energy and information with its surroundings in the process of information metabolism, every living organism – from the simplest to the most complex – tries to preserve its own order. The loss of its order means victory for the Second Law of Thermodynamics (the entropy law) and spells death. Despite a living organism’s apparently stable condition, none of the atoms in it remains fixed; after a time it is replaced by another atom coming in from the outside. The only thing that remains stable is the structure of the living organism, the order specific for that organism. This specificity, in other words its individuality, applies both to its order at the biochemical level (viz. the specific nature of the organism’s proteins), on its physiological and morphological levels, as well as its order on the information level.

The type of order concerning information relates to the signals a living organism receives from the surrounding world and its specific reactions to them. Thanks to information metabolism not only my own body is “mine;” so, too, is the world around me, which I perceive, experience, and react to in the manner which is proper to me. As a living organism’s nervous system develops phylogenetically, its information metabolism starts to play a more and more important role with respect to its energy metabolism.

To maintain its specific order an organism has to make a continuous effort, on which its life depends. It may be spared some of the effort that has to be expended to withstand entropy, preserve life and fend off death. This happens through biological inheritance, thanks to which an organism’s specific order is handed down from one generation to another. Sexual reproduction ensures a greater variety of structures, for the genetic plan that is created when two reproductive cells are joined together is new, not a true copy of the parent cell’s plan, as happens in asexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction resembles technological manufacture, in which the models that come off the production line are exact copies of the prototype.

Apart from biological inheritance, humans also have social inheritance at their disposal, thanks to which they may acquire specific material and spiritual values. Straight after birth the human individual starts to assimilate the work of thousands of generations to develop speech, writing, knowledge of the world, moral and artistic values, technological progress etc. If he or she were deprived of this legacy there would be the need to start from scratch. Cultural development would be impossible.

There is an inherent link between order and power. To convert one’s environment to one’s own order and the structure of one’s organism, one must first subdue that environment, become its lord and master. The power struggle for control of one’s habitat is not only a human attribute, but is also found in animals and even in plants. Animals react aggressively or flee whenever an intruder tries to encroach on their territory, a trivial example of which is a dog growling at anyone who tries to take away its bone. Animal sociology supplies many interesting examples both of power struggles as well as of social hierarchies, for instance the familiar pecking order observed in a henhouse.

The phenomenon of power also occurs in multicellular organisms. There must be order in a “society” consisting of billions of cells. This order is encoded in the genetic matter that makes up the essential part of the nucleus of every cell. The nucleus is the cell’s “authority”, without which it could not exist. The endocrine and nervous systems perform as it were auxiliary roles in an organism with respect to its genetic plan and reinforce its integrating operations, modelling the organism’s activity plan depending on needs and environmental conditions.

A neoplastic disease could be described as the “rebellion” of a cell against the order prescribed in its organism. Having discharged themselves from general discipline, neoplastic cells pursue a right to a life of their own and the life of their new species, in total disregard of the rest of the host organism. They develop and replicate at the expense of other, “loyal” cells.

If we take a look at the organism as a whole we cannot miss the question of power, which makes an appearance even in organisms at the lowest phylogenetic levels. To live and reproduce, an organism must appropriate its surroundings. This issue, like many others that are fundamental to human life, occurs in a pathologically bloated form in schizophrenia as well. Especially in an acute phase of schizophrenia, a patient’s abnormal experiences will often make them oscillate between a feeling of divine omnipotence in which they can read other people’s minds, control their will, and determine the course of events on earth and in the universe; and a sense of utter loss of power, when others can read his or her mind, direct his or her movements, speech, and thoughts, as if he or she were a robot under the absolute power of the outside world. The lives of schizophrenia patients prior to the emergence of the illness are often marked by difficulties with finding a place for themselves in the world that surrounds them and a solution to the “I rule and am ruled” dilemma.

The question of power is associated not only with an organism’s right to preserve its life, but also with the right to propagate its species and with its information metabolism. In the first case power is unidirectional, while in the second and third case it takes a two-way form. The part of the environment which has to be destroyed and absorbed to supply the organism with the energy it needs to live no longer has any power over it. But in sexual and erotic relationships power works in both directions. The partners are each other’s master and slave. In the exchange of signals with their environment each of them must accept the order of that environment while at the same time trying to impose his or her order on it.

The possessive adjective “my” defines three kinds of power over the surrounding world. Things like food, a home, money etc., objects needed to secure the right to live, are “mine.” “Mine” are also the persons who secure “my” right to propagate “my” species – in the immediate sense “my” sexual partner, and more generally the people who belong to “my” social group: “my” family, nation, religion, profession, class etc. The right to propagate the species lies at the very foundation of all manner of social relations. The family, which is the simplest and primal type of social relation, is a direct outcome of this right. Finally “my” personal experiences, impressions, emotions, thoughts, knowledge, decisions and actions are all “mine.” The signals I receive from the outside world are all arranged in a specific order, determining my specific reaction to them.

Information metabolism, which Pavlov defined as conditional and unconditional reflex, extends the organism’s range of power over its surroundings. What becomes the organism’s “own” is not only that part of the surroundings which it assimilates and absorbs, and not only that part with which its temporary union is the condition that determines the emergence of a new organism, but a much broader part of the surroundings, from which minute amounts of energy, too small to play any part in the metabolism of energy, serve as signals conditioning the organism’s behaviour. An organism’s information metabolism is the preliminary step before it embarks on assimilative and reproductive contact with its surroundings. Before the surroundings become “my own” in the sense of building up my organism or of sexual union, they have to become “my own” in the sense of my being able to find my way in them. The organism has to “know” how to move about in its surroundings in order to fulfil the two fundamental biological principles: to preserve its own life, and to propagate its species.

If by the essence of “life” we mean the observation of these two fundamental biological principles, then the life of an organism becomes more and more of a preparation for “life,” the more phylogenetically developed the information metabolism which exists in each of its cells in the form of their ability to receive and respond to stimuli coming in from the outside world. In multicellular organisms information metabolism becomes the domain of cells which specialise in this: receptor cells which receive stimuli, effector cells which respond to stimuli, and nerve cells which transport and put them in order. On the other hand in the simplest organisms all that life entails is the fulfilment of the fundamental principles of biology, and there is only a minimum of preparation. The simple organism only absorbs its surroundings into its own structure; its environment is entirely “its own” world; but, should the environment fail to meet this condition, it will pose a threat to the existence of the simple organism, an assault and devastation of its order, which is tantamount to death. If we could make an attempt to reconstruct the experience of living beings at this level of phylogenetics without lapsing into fantasy or speculation, we could suppose that they oscillate between a feeling of omnipotence and a sense of being threatened with death. The world would be either “fully theirs” or “absolutely alien,” and in the latter case it would spell death for them.

The satisfaction of the fundamental biological needs is associated with pleasant experiences, and failure to satisfy them is connected with unpleasant experiences. The organism finds “its own” world attractive, and is repelled by an “alien” world. Thus having power to control the outside world is a source of pleasure, whereas lack of power is a source of unpleasant feelings. An alien world gives rise to anxiety and aggression, the desire to escape or destroy it.

There is a certain analogy regarding power to control one’s surroundings between the situation of beings at the lowest levels of phylogenetics and the situation of a human at the very beginning of his ontogenetic development, when his signalling system is still at a very early stage of functional growth. Like the lowest life forms, a human foetus or infant is absolutely dependent on his environment, without it they would cease to exist. Their environment is entirely theirs; it wields absolute power over them for it satisfies all of their needs or, should it not do so, the baby is likely to die. Many psychiatrists, especially those whose work deals with the experiences of early infancy, believe that one of the experiences characteristic of infancy is the sense of omnipotence and the lack of a distinction between the baby’s own world and its surroundings. The fairly high incidence of experiences of this kind in schizophrenia is regarded as the patient’s regression to the earliest stages of development. Despotism is generally considered an axial symptom of emotional infantilism. Absolute power is associated with absolute dependence. Like the baby deprived of its mother, the prince cannot exist without his subjects. Also, he is liable to fail to notice the boundary between himself and the surroundings subject to him, in line with Louis XIV’s famous dictum L’état c’est moi and in contrast to King Canute, who knew he had no power to command the tide of the sea to stop.

As the signalling system develops, the organism becomes less dependent on its environment. Contact with its surroundings does not mean that the organism is obliged to take full possession of and absorb them into its own system; neither does it mean the opposite, that the living organism is transformed into the structure of its surroundings.

The developed organism’s contact with the world is not marked by such a clear-cut “win‑or‑lose” alternative. Its success does not entail the annihilation of its surroundings; neither does the prevalence of its environment spell death for the organism. Its struggle against its surroundings continues, for this is the sense of life, if by “life” we mean the living being’s endeavour to preserve its own order at the expense of the order of the outside world. Nonetheless its successes and its setbacks lose the dramatic “either‑or” aspect of “to‑be‑or‑not‑to‑be.” Instead they turn into more of a make‑believe battle, a game against the environment. In this game the organism can lose against the environment without having any penalties inflicted on it other than the imposition of the environment’s order. In effect this is what discipline means in the sense of learning the order of one’s environment. Or the organism can be the winner, in which case it imposes its own order on its environment without the need to entirely destroy it as in the metabolism of energy. These “games” played with the surrounding world tend to turn into an end in themselves. They may be observed even at low stages of phylogenetic development. Huizinga’s concept of homo ludens (“man at play”) appears to be applicable not only to humans.

The organism’s interaction with its surroundings in the sense of its reception of signals from the outside and its response to them – an exchange of signalling in which it is alternatively winner and loser – is a necessary condition for the saturation of its information metabolism, without which its energy metabolism and reproductive contact with its environment could not develop in the right way. In other words, the living organism cannot attain the essence of life, the satisfaction of the two fundamental biological principles, unless it passes through an insulating zone in which it toys with the outside world, and in which contact with the outside consists in the mutual exchange of information. As I have already said, as the signalling system develops this insulating zone expands. In extreme cases of schizophrenic autism, that is when a disruption occurs in a person’s information metabolism, disturbances may be observed in his or her energy metabolism, for example the patient may stop eating; and practically in all such cases the principle of species propagation is blocked, too.

The evolutionary advance charted by the emergence of humans generally applies to the incommensurably advanced development of their signalling system, as compared to other systems in their body. This advanced state pertains especially to the part of the human signalling system which is responsible for the integration of incoming and outgoing signals, that is the cortex of the human brain. Billions of cortical cells give the human individual an incredible plethora of means (functional structures) whereby he or she can exchange information with his or her surroundings. Only a small fraction of these are used during an individual’s lifetime, in accordance with the principle of prodigal economy, which is pretty widespread in the living world. On the same principle only a small percentage of nature’s genetic plans eventually develop into mature organisms.

And on the same principle, too, the body organs work at only a fraction of their maximum efficiency. Environmental pressure, especially from an individual’s social environment and inheritance, force him or her to develop only those forms of interaction with the surroundings which are approved in the given culture and historical period. Maybe chaos would ensue if we did not have this external pressure and social discipline. Perhaps due to a subconscious anxiety of chaos, from the very origins of their existence human beings have always striven to create all manner of devices to restrict the freedom of the people, animals and plants they comes into contact with, and to limit their own freedom as well. Wherever there are chains and fetters you can be pretty sure you are dealing with the handiwork of humans.

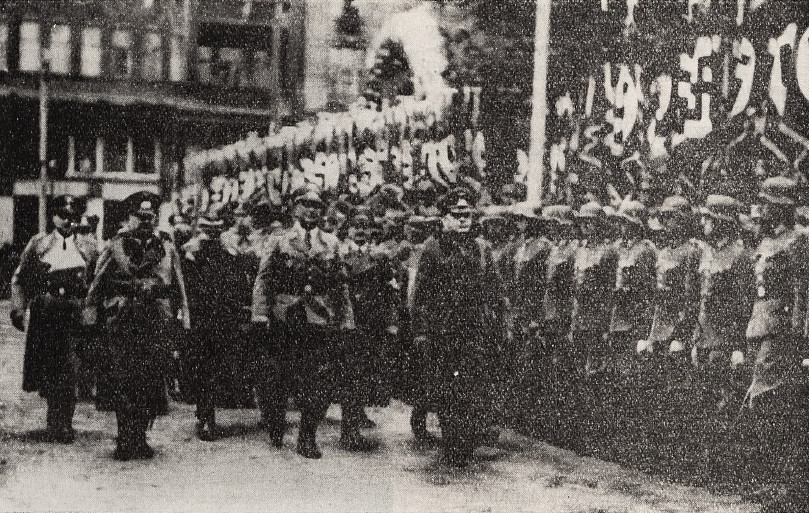

If we try to look at the question of order and discipline through the eyes of concentration camp survivors it’s hard not to agree with prof. Miodoński’s words quoted at the beginning of this article. In those places the effort to impose order and discipline achieved the climax of gruesome absurdity. Even when the Third Reich was about to fall its death factories were still working efficiently, they were even increasing their “productivity.” The main idea of Hitler’s Mein Kampf survived for the longest time in them; they were its quintessence. The Nazi concept of how to improve the world was exceptionally simple: destroy everything that was a threat to the racial purity of the Übermensche, above all exterminate the Jews. After this act of destruction was accomplished a “paradise for the magnificent” was to ensue. The concept was by no means novel in human history, but never before had it been formulated in so simple a manner and carried out so persistently.

In every social ideology – and there have been quite a few over the ages – there is always an element of aggression with respect to whatever is not in compliance with it, primarily to those who are not its adherents. The world is simplified to a black-and-white picture, and people are divided into “believers” and “non-believers.” The former are the good guys and the latter are evil. The inner struggle between the various potential activities, which an individual tends to perceive as the battle between good and evil, is externalised. By accepting a readymade formula for activity, the individual reduces the extent of his or her misgivings and is good for as long as he or she abides by the formula. Whatever is outside the formula and not in agreement with it is bad. Acceptance of the readymade structure that is provided from the outside facilitates the individual’s inner integration; his or her dynamic order changes into a static order, and the frail reed turns into a monumental pillar of strength. The model human propagated by the Third Reich was such a monument, marching straight ahead towards the goal set by the Führer, destroying and trampling underfoot everything that stood in the way.

The development of the signalling system in humans, and especially of its supreme, verbal mode gives them far more scope than animals have at their disposal for the use of readymade functional structures. Instead of having to start from square one, the human individual simply learns these structures from his or her environment. Discipline is a necessary condition for the individual to be able to assimilate these patterns of behaviour from that environment. Their acceptance is rewarded, and their rejection is punished. An external system is established to control the individual’s behaviour, perceived by him/her as “the social mirror” (“what will they think of me?”).

As the assimilation of the new functional structure proceeds, the external system of control is internalised and integrates with the individual’s system of self-control. The power to judge passes from the environment to the individual, who becomes his or her own judge. The social mirror is internalised and becomes part of the individual’s conscience, the Freudian superego or the Socratic daimonion.

The conscience of Third Reich man was his Führer’s command. He experienced a sense of guilt if he failed to carry out that command adequately. The neurosis Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz, suffered from in the camp was an outcome of his feeling of guilt not for killing hundreds of thousands of victims, but for not carrying out the extermination as efficiently as was required. His neurotic symptoms diminished when the extermination methods were enhanced by the use of the gas chambers. The fact that the war criminals notoriously lacked any sense of guilt was a consequence of their internalisation of the Führer’s command. Conversely, one could as well wonder at anyone who should feel innocent if accused of behaving in compliance with the Ten Commandments.

Adolf Hitler and his officers

One of the essential properties of every signalling system, both technological and biological, is its ability to exercise self-regulation. In its basic scheme such a system may be described as follows: arriving external signals are transformed into the system’s special language (e.g. an electrical impulse is received by an electronic device, or a nerve impulse by the nervous system). Transformed signals are then integrated according to a plan, which is fed in from the outside as software in the case of electronic devices, but is developed internally in the case of biological systems. The result of the integration is transmitted in the form of a command to the effectors (e.g. the muscle cells in biological systems). Here the intrasystemic signal is processed into an externalised signal, in other words the language proper to the system is translated into a language comprehensible for the system’s environment. The final stage of the exchange of signals is feedback, and this is the phase which determines the system’s ability to exercise self-regulation. Feedback means that some of the signals transmitted by the system into its environment come back to it. Thanks to this the system’s plan is never permanently fixed. It changes in accordance with the returning signals, which carry information on how the plan has been carried out and what changes it has effected in the environment. There are numerous examples of feedback in the nervous system. At the highest level of integration of the nervous system’s functions, the level at which a given activity is performed consciously, the counterpart of feedback is perceived as the system’s ability to exercise self-control. The “social mirror” would correspond to those feedback signals which report the effects of our behaviour on the environment; while “conscience” would be evoked by the integration of feedback messages with our most general, and hence conscious, plan of activities (viz. by internalisation).

For the inmates finding themselves in a concentration camp was tantamount to the shattering of the “social mirror” they had been used to hitherto. Everything that they had been until that time no longer mattered; now they were just numbers. They had three options to choose from: 1) to perceive themselves through the eyes of an alien environment, viz. to be just numbers in the camp; 2) to preserve their old images of themselves, which was unrealistic but to a certain extent mitigated the dreadfulness of the first option; or 3) to identify with the group in power and adopt their modes of behaviour, turning from a number into a commander, at least in the eyes of fellow prisoners. Life in the concentration camp forced prisoners to oscillate between the three options, especially between the first two of them.

One of the phenomena of life is a fluctuating equilibrium between changeability and permanence. An organism’s activity plans are changing all the time, yet its basic line of development remains the same. The more frequently a plan (functional structure) is carried out the more it becomes established and is performed automatically. A toddler stumbles and falters as it walks, it needs to exert a lot of effort to walk; but after a time walking becomes a mastered, automatic function, performed strictly in accordance with a specific scheme. But we must not forget that the scheme is subject to continuous modulation depending on feedback signals, especially proprioceptive signals, and hence it has a certain degree of inherent lability. However, the level of uncertainty is not very high, for the nervous system need not be fully engaged in the performance of the plan of the motor function. That only happens when the implementation of the plan becomes hedged with difficulties for some reason or other, e.g. due to tiredness or an unusual terrain. At such times every step is a conscious operation. Awareness, that is the full engagement of the nervous system, is as it were held in reserve for the most difficult activities.

Moreover the adoption of a particular social ideology reduces the individual’s sense of insecurity associated with the very fact of existence and the need to select the right way to behave out of many potential options. The higher an organism’s evolutionary level, the greater the number of potential options of behaviour (functional structures) an individual has to choose from, and hence the greater the sense of insecurity, the more his/her balance fluctuates. This human state of insecurity and indecision is expressed by the Cartesian maxim, Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”).

However, while on the one hand the evolution of the living world in its resistance to entropy is proceeding towards the creation of new, richer morphological and functional forms better adapted to life (and has its greatest creative freedom in the functional forms that are described as thinking); on the other hand the opposite tendency may also be observed in Nature, a tendency to slow down the dynamics of evolution, as if frantically holding on to old forms, often no longer well-adapted to life, and sometimes overtly dangerous. This phenomenon illustrates an idiosyncratically conservative streak in Nature, her immutability in a sea of constant flux and change, one might even say her inertia, her shunning of creative effort.

Humans, who consider themselves the peak achievement of evolution on this planet (though perhaps not without grounds), thanks to the development of their nervous system and especially of their cerebral cortex, have at their disposal an infinite potential for the creation of new functional structures. If new functional structures are the benchmark of the rate of evolutionary progress, then on the principle of counterbalance in processes running in opposition to each other there will also be a marked tendency for reverse trends to occur, i.e. retardations in evolutionary progress curtailing the creation of new functional structures. So it is by no means a coincidence that all the diverse clamps on freedom, prison chains and fetters etc., are a specifically human feature.

The discipline of upbringing and education depends to a large extent on prohibitions. Only a few of the many potential functional structures have the right to develop, others must be repressed. That we walk, talk, write etc. in a particular way is not only due to the fact that these are the forms of behaviour which have been developed through education, but also that other potential forms have been inhibited. The learning process may be described most readily on Pavlov’s stimulation and disincentive scheme. When a toddler learns to walk, at first he or she makes many unnecessary movements, which are then gradually discarded. A preschool child’s drawings are usually richer both subject-wise as well as in terms of form than the drawings of a child of school age, who has been introduced to the specific forms of expression used in drawing. The variety of schizophrenic experiences may be explained as a discharge of behavioural forms inhibited in a patient’s life prior to the outbreak of the illness. The training of Hitler’s Übermensche entailed the repression of humane emotions and the stimulation of aggressive and sadistic emotions.

Social ideologies, which to a greater or lesser extent aspire to the shaping of the whole of human behaviour, involve the encouragement of some forms of behaviour and the deterrence of others – just as learning less integrated activities does. What makes them dangerous is their all-embracing character. When a baby learns to walk and occasionally goes back to an ontogenetically earlier type of locomotion such as crawling it is still the same child, for the motor functions are only a segment of its behaviour. Environmental pressure in such a case is limited to approval of one form of behaviour and rejection of another behaviour. But in an all-embracing assessment of the behaviour of an individual who transgresses a social norm it is the individual as such who is rejected by the group for breaching any of its rules.

Of course an all-embracing assessment is hardly ever truly all-embracing. Often a minor detail – a different skin colour, a hooked nose, a strange kind of apparel, a foreign language – will prove sufficient to cast someone out beyond the pale of what is familiar and understandable, to brand him an alien, or even an enemy. It’s hard to answer the question where this facility in the assessment of another person comes from, whereby on the basis of just one trivial feature he or she may immediately be separated off from the sheep and put with the goats. Perhaps this extreme, sometimes even grotesque scheme is an expression of the biological tendency to delimit borders between different systems. For instance, cells which perform a specific function and have a specific structure separate themselves off from other groups of cells with different functions and structures by a wall of connective tissue, one of the functions of which is to serve as a boundary dividing up the billions of cells in an organism into smaller communities of cells for the various functions and tasks. On the other hand the tendency to set up barriers is counter‑biological, because it impedes natural evolution, which can only proceed if the diverse life forms can coexist alongside each other in harmonious interdependence, and if related life forms can mate, giving rise to new life forms. Therefore in the biological sense boundaries are never hard and fast; they are always penetrable in some way or other, allowing for the mutual influence of life forms of one kind by another kind.

As a rule, all-embracing assessments of another person as a result of which he or she is automatically ascribed a place on one or other side of the boundary and becomes either “one of us” or “one of them,” carry a strong emotional charge. This kind of division corresponds to the fundamental orientational tendency, in which the individual can assume one of two attitudes to his/her environment: either the “towards” attitude, or the “away from” attitude. In humans this tendency is steered mainly by the phylogenetically older parts of the nervous system (the rhinen- dien- and mesencephalon) and it is associated with a strong vegetative discharge, and subjectively with a feeling of anxiety and hatred in the case of the “away from” attitude, and desire in the “towards” attitude. In such situations the gnostic functions, which in humans are associated primarily with neocortical activity (in the youngest phylogenetic part of the nervous system), are down to a minimum. The differentiated image of the world is simplified down to the objects which are to be avoided or destroyed, and those which are to be espoused – in sexual union, or at any rate in the bonds of a closely-knit tribal, national, ideological etc. community. Once the emotional tension associated with the fundamental orientational attitude is over and the gnostic process can again proceed, the individual is often surprised to find that the object he or she had desired was not so beautiful after all, and the object stirring up his or her anxiety and hatred was not so repugnant.

Social ideologies have another appealing feature apart from an externally imposed order which reduces the individual’s sense of chaos and insecurity. They offer the individual the opportunity to “let off steam” – release his/her positive emotions on fellow-believers, and his/her negative emotions on non-believers.

We are not able to acquire a knowledge of everything that surrounds us, and one of the peculiarities of human relations makes us incapable of passing each other by indifferently, since indifference is itself a negative attitude, treating another person like an inanimate object. We are forced to make a fundamental assessment and label other persons as belonging either to “us” or to “them,” sometimes on the grounds of the most superficial evidence. In times of war decisions whether to “approach” or to “move away” turn into “comrade-at-arms” or “enemy” labels, and mistakes in the identification of friend or foe may prove fatal. Wearing a uniform becomes a necessity.

The romantic appeal of a uniform and esprit du corps, concepts which lost some of their glamour during the Second World War, are nothing more than a sign that the individual has become an integral part of a social group, that he has lost his individuality, “I” has been replaced by “we,” and instead of each of them exercising their own will, they follow the will of their commander, who carries the full burden of responsibility for their actions. The appearance of a different type of uniform may be a signal for them to attack or to flee.

The attributes of power may be listed in the three following points: responsibility, solitude, and dependence. The burden of responsibility is an outcome of the fact that the commander’s functional structures become the functional structures of his subjects, thereby being replicated and amplified. Every gesture or facial expression the commander makes, every word he utters becomes meaningful; they matter because they are immediately taken up by the members of the group under his authority and put into practice. Thanks to their manifold reproduction by the group, the commander’s ideas are readily turned into action. One of the aspects in the education of commanders and leaders such as hereditary princes, diplomats, military commanders, princes of spiritual power etc. was training the prospective leader to keep the expression of his emotions under control, for the slightest twitch on his face could have far-reaching consequences. The leader’s face would often be hidden behind a mask and unfathomable, and his gestures scant and well‑rehearsed. The democratisation of power brought down internal discipline in this respect.

Arthur Greiser, one of the organizers of the Holocaust

The ability to replicate its functional structures is a property shared by all steering systems, whether technological (as in the automation of production) or biological (DNA and RNA reproduction, the generalisation of the functional structures in the nervous system). This ability gives a commander a feeling of power, but on the other hand it deprives him of a sense of ease and individuality. His exchange of signals with the outside world ceases to be a game, for the very fact that his signals are reproduced many times over carries serious consequences. Perhaps that is why kings and princes liked to have jesters in their courts and sought respite in entertainment that sometimes was quite orgiastic; in this way they could free themselves for a while from the gravity of their signals.

A commander has to realise that his signals (words, gestures, facial expressions etc.) will be read and reproduced by many people, turning into commands for them and making them try to follow him. A commander cannot be himself, he is only what he is supposed to be in accordance with the idea he represents and with how his adherents want to see him.

According to the testimonials given by concentration camp survivors only a small fraction of the SS-men’s macabre cruelty was caused by their sadism; usually it was due to them wanting to show that they were “good Germans,” for whom Mitleid ist Schwäche (sympathy was a sign of weakness); it was an outcome of their anxiety not to be excluded from the ruling group, and showing weakness could be tantamount to a sentence of death. The cruelty of the capos in the camp, which often went beyond the pitilessness and implacability of the SS, was an outcome of their desire to “be as good” as the commanders, with whom they identified. It is well‑known that converts tend to be more zealous than old believers. On changing into civvies an SS-man could again turn into a “decent” German, especially as he had no pangs of conscience, since what he did in the camp was not due to his own will, but the will of his Führer.

The measure of a steering system’s reliability or soundness is its capacity to implement the plan which it represents. This applies to technological and biological systems alike. A refrigerator is good if it maintains a low temperature regardless of external conditions. The nervous system is working efficiently if it allows the organism to develop in the right way in spite of problems in its internal and external environment. A commander is good for as long as he is successful. Once the successes stop the idea turns into an illusion, which is what most people now consider the Nazi ideology to have been. A commander is sustained by his victories, without them he perishes. Victory is a proof that what he is fighting for is not make-believe. Victory turns the plan into reality. Usually a commander and his adherents find it hard to accept defeat as a fact, since it means that they have nothing more to live for. The idea which they lived by loses its sense: along with its implementers it has become useless, like a fridge that is out of order. Towards the end of the Second World War, when Germany’s defeat was only a question of time, many Germans along with their Führer held on to the illusion that victory was still possible. What’s more, even after defeat there are still people who harbour such a delusion. Every defunct ideology leaves its residue of diehards.

In an ideology the necessity to put the plan into practice implies a singular attitude to the environment, best characterised by the well-known saying “the end justifies the means.” What is most important is to accomplish the aim; any means which lead to that are good. The attitude to life adherents of an ideology exhibit is reduced to the alternative “victory or death.” This is the attitude characteristic of energy metabolism. What’s most important for a commander is not an abundance of functional structures, which is paramount in the metabolism of signalling, but the power he has. His power determines whether the aims he represents will win over the environment. The commander’s environment is either submissive to him and helps in the implementation of his plan; or it is resistant, in which case it is hostile and must be coerced or destroyed. The consequence of such an attitude to the environment is the need to fight it. From the point of view of evolutionary biology unremitting battle means a regression to the level of energy metabolism; life is divested of everything that in the course of evolution has acted as a shield against the cruel rigour of the “win or lose” principle. The need to fight for power is an outcome of the very nature of power, and by its very nature the struggle for power is merciless. Loss of power means annihilation, just as in the metabolism of energy an organism which does not transform the structure of its environment into its own structure is itself transformed by its environment, on the “eat or be eaten” principle. No wonder, then, that commanders deliberately or sub-consciously evoke wars, which are a test of their strength, and hence of the reality of their power.

In the eyes of the commander a human individual is worth as much as he or she is ready to carry out the commander’s aims. A worker’s value is determined by the extent to which they are carrying out the duties their boss has set them; a soldier’s value is determined by whether or not they are carrying out orders etc. Even in a concentration camp, where the individual was worth nothing at all since death was the destiny assigned him or her, there was still a hierarchy of value determined by the function a particular individual performed. Functions and duties played an important role in the organisation of the camp; some of the power of the SS devolved on some functions (e.g. the function of capo), which helped some of those who performed them to survive.

In every steering system some of the “the royal grace” passes down to the lower levels of the hierarchy, thanks to which each of the links in the long chain of events from the plan to its full implementation is a representative of the main idea. This principle relating to the reproduction of the plan and devolution of power applies to all steering systems regardless of whether they are technological, biological or sociological. The plan encoded in a self‑steering machine is implemented in successive stages, each of which brings the task forward and closer to completion. At each stage the plan passes down to lower levels of execution representing the whole or part of the central plan. Each of the machine’s components is steered by a component higher up and nearer the central plan; at the same time it steers a component which is lower down and nearer the final effect. The genetic code in the structure of the DNA in the cell’s nucleus controls the synthesis of RNA, which in turn controls the synthesis of the cell’s proteins and enzymes, and they in turn control the cell’s physiological and biochemical processes. Before the commander’s plan is achieved it has to pass down all the levels in the hierarchy. Each level acts as a commander with respect to the level below, and a servant with respect to the level above. The commander, who has no superior over him, generally tends to be responsible “to God and history.” In human relations the hierarchical nature of power is a convenient way to release pent-up feelings of aggression, in accordance with the pecking-order rule observed in animals. Hence there is a natural tendency for the individual to climb the ladder of power, which gives him more chances to peck and saves him from being pecked. Individuals who managed to be appointed to a function in the concentration camp enjoyed the usual privileges associated with power, such as better working conditions and better food, but they were also protected against some of the impact of the aggression that was the lot of all prisoners; hence functionaries stood a better chance of survival. On the other hand they were often faced with a severe moral conflict: how could they resist the carrying out of Hitler’s extermination plan if they were themselves a link in its implementation? Moreover it called for a huge amount of willpower and feelings of benevolence on the part of such functionaries to withstand the temptation to exercise their power on those who were weaker, as usually happens in such situations.

One of the properties of biological steering systems is their high degree of flexibility, viz. their ability to change their plan depending on needs and the current situation inside and outside the organism. Recent discoveries in molecular genetics have shown that the genetic plan has a high level of flexibility, and the activity plans (functional structures) of the nervous system have for a long time been known to be labile. Despite the advances made in feedback devices, technological steering systems are still far behind as regards achieving such a high level of flexibility, and their capacity to adapt is not as good as in biological systems. The level of flexibility in sociological steering systems seems much closer to the technological rather than the biological systems. The ideas, social standards, attitudes etc. that govern the life of large human groups tend to be rigid and immutable despite the changeability of the conditions in which people live and the diversity of the human types which have to abide by them. Perhaps this is due to the very nature of the human mind, which holds on tightly to its old, conventional ways, as if it were fending off a potential abundance of diverse forms.

Unrelenting struggle exacerbates the inflexibility of a social ideology. Even a slight departure will turn the dissident into a heretic or enemy who has to be destroyed. The situation is like a vicious circle: in order to make the idea a reality, not a fantastic dream, you have to fight for it; the atmosphere of battle rigidifies it; and inflexibility intensifies the atmosphere of hostility.

Inflexibility is associated with implacability; there is no possibility of any kind of change in the plan, it has to be implemented at all costs. The situation is like the steamroller which concentration camp inmates had to pull or be crushed by it. Absolute discipline is required at all levels of the hierarchy; you have to carry out your orders and see to it that those who are subordinate to you carry out theirs. The assessment criteria for an individual depend on how well he or she carries out his task. The other qualities do not count. The power system impoverishes the image of other individuals, and hence also the diversity of human relations. Above all it disables freedom of choice, turning the individual into a robot. The vital effort associated with the continual creation of new forms and the need to make a choice out of them, which entails hesitation, uncertainty and perpetual anxiety, is reduced to the acceptance of just one form, while the individual’s anxiety is generated not by the difficulty of choice but by the apprehension that they are not properly carrying out the form which they have adopted or had imposed on themselves, which spells their condemnation and expulsion from the group subject to the given power system. Often it will mean their destruction, for whatever is not in line with the system’s aims is automatically hostile.

The solitude of the commander is an outcome of their attitude to the environment, which can be imagined in geometric terms as a plane. That plane is always slanted. The commmanders have the plan of action before their eyes, and the environment is the fabric from which the plan is to be effected. Thus they look downwards on the environment, they have it within the range of their power. Should the environment rise and stand up to them, they will become anxious and aggressive. Creativity will turn into war.

Relations with one’s environment are far richer if the plane of attitude is horizontal, when there is no need to impose anything on the environment, or indeed adopt anything from it against one’s will. The principle of freedom of choice, not coercion, prevails in a horizontal plane, whereby the environment becomes more familiar, because one has to understand it before one can accept or reject any of its forms. Contact with one’s environment is more like a game or a dialogue (to use a fashionable word) rather than a battle in which one is either a winner or a loser. On the other hand a potential structure becomes real only if it is externalised and becomes part of the environment. Thus the tendency to transform the environment becomes a necessity without which life would be merely a dream. The concentration camp inmates were subjected to such severe pressure from their environment that deliberate activity as a result of their free choice was out of the question, at least in the initial stage. They were like robots, pushed about and beaten by all. The reality surrounding them had something of a nightmare about it, despite their very painful contact with it. Deliberate withdrawal from activity leads to a state of nirvana in which the boundary is blurred between the individual and the world around, between the world of dreams and reality.

Finally we must not forget that we cannot learn about the world that surrounds us unless we take action and transform it. A child takes up an object that it finds interesting and tries to look inside it. The scholar behaves likewise. Frequently the cognitive process involves the subjugation and destruction of the object under observation. In this type of cognition our capacity to control a given phenomenon is a measure of how much we know about it. But there is also another kind of knowledge, the aim of which is not control of the environment but logical construction. As Einstein wrote, “The object of all science, whether natural science or psychology, is to co-ordinate our experiences and to bring them into a logical order.”

The external expression of the solitude of a steering system is its isolation from direct contact with its surroundings. In technological devices the steering system does not take an active part in the machine’s energy exchange processes with its surroundings; it merely controls them, more or less isolated off from the rest of the machine’s parts. A cell’s steering system (its chromosomes) is separated off by the nucleus membrane from the rest of the cell. The blood-brain barrier separates off the nervous system from direct participation in the organism’s metabolic processes. In fairy stories and legends the king puts on a disguise to visit his subjects, but in reality a ruler only rarely comes into direct contact with his subjects, for his authority diminishes on close contact. By showing him to millions of viewers television may prove much more dangerous for his authority than all the attempts to democratise power hitherto.

For a person as a social being isolation is hard to bear. A prince is always surrounded by coteries, groups of intimate advisers, counsellors and jesters. The plane of contact between them and the prince is more or less horizontal; very often they are the ones who rule him. So even a prince cannot be free of the rules that govern human relations. One cannot merely control other people; one is inevitably controlled by others as well; one cannot only issue commands, since that would impoverish the exchange of information; one cannot look down on others all the time, for humans gaze in many different directions. To rule one must keep one’s distance. When the plane of view between a prince and a subject changes from an inclined gradient into the horizontal, often they will be mutually astonished to find that they are similar to each other, that they share the same human virtues and vices. The splendour of power will fade. The ruler and the ruled will again be human; no longer will the ruler be able to control the ruled like a robot, and the grandeur of the aims to be achieved will shrink on contact with the reality of another human life. The subjects will no longer see their lord as an implacable deity or a machine that will crush them at the slightest sign of resistance, but as a human who is trying to understand, or even to help them.

In the concentration camp every gesture, every grimace, every syllable uttered by its commanders could have meant a death sentence or excruciating torture for an inmate. Their very appearance was so terrifying that they grew in stature into apocalyptic beasts. However, it did happen that by a lucky chance an inmate would encounter their master on a less slanted plane and could make a deal with them, or even control them to a certain extent. At such times the master’s apocalyptic nature would disappear, and what remained was human paltriness. In the master’s eyes the number in prison rags would assume the features of a human being, wtih whom it would even be possible to have a conversation. From the perspective of organisation of a death camp it was right for the SS men to keep their distance. They generously “bestowed their royal grace” on certain carefully selected prisoners, usually criminals, investing them with the power to torture and kill – for in a death camp power was about killing. If the SS men themselves had come into closer contact with inmates, they might have discovered human beings in them, quite like themselves. This sometimes happened. The classic example is Höss’s gardener, a Polish inmate whom the supreme wielder of power in Auschwitz treated like a human.

In all steering systems there is a mutual dependence between the one who issues commands and the one who carries them out. Neither can the master exist without the slave, nor the slave without the master. A machine consisting only of a steering device without any operational components would be utterly useless. The nucleus cannot live without the rest of the cell, nor the cell without its nucleus. A brain cannot live on its own without a body; and conversely, the life of a higher organism is hardly imaginable without a brain. Bereft of his subjects, even the mightiest king will probably end up in a psychiatric hospital. Even in the smallest human groups there is a tendency to establish a leader who will embody the forces integrating the group. If deprived of its leader, the group will disintegrate.

However, the mutual dependence of the ruler and the ruled is not always correctly understood and implemented, and their relationship may become artificial. Convinced of having the right to rule, the masters may demand absolute obedience, forgetting that they are merely the representative of the tendency prevailing in the group subject to their authority, and that this tendency should find its expression in them. On the other hand, if a subject does not identify with the things they are expected to believe or do, they will rebel, either openly or in secret. In the former case they will incur the master’s anger; in the latter they will be hurting themselves, since by carrying out orders they will have to be at war with themselves. Or they will accept the scheme imposed on them and blindly carry it out, thanks to which they will feel they are part of the power structure, secure in a sense of order they were unable to work out for themselves. An artificial structure will have replaced their own structure. By forfeiting their freedom they will be spared the effort to set themselves in order, their chaotic condition will be replaced by an artificial order, and their insecurity and anxiety alleviated by unswerving confidence in the idea they have espoused.

Thanks to the development of the media and the historical disciplines, especially archaeology, mankind today has a much better chance than a century or even a few decades ago to learn about many different lifestyles. Hence an individual’s self-confidence in the chosen or inherited lifestyle is falling. He or she is not so keen to impose that way of life on others, especially as the memory of the last War brings it home where that could lead to. If Auschwitz and Hiroshima have become symbolic of that War, then due to them the problem of power and the associated problem of war have now reached a critical point, and call for reappraisal.

Translated from original article: Kępiński A.: “Refleksje oświęcimskie: psychopatologia władzy.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1967.

References

1. Einstein A. The Meaning of Relativity. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton, U. Press; 1955: 1.2. Huizinga J. Homo Ludens. Paris: Gallimard; 1925.

3. Schrödinger E. What Is Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1948.

4. Sehn J., Kocwa E. (Eds. and Trans.). Wspomnienia Rudolfa Hössa [Memoirs of Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz, translated from German into Polish]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Prawnicze (3rd Ed.); 1965.