Author

Roman Leśniak, MD, PhD, 1928–2003, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy. Member of the resistance movement during the Nazi German occupation of Poland.

A group examination of former prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, carried out by the Department of Psychiatry at the Medical Academy in Kraków in 1959-1961 (Leśniak et al., 1961; Leśniak, 1963; Orwid, 1964; Szymusik, 1964; Teutsch, 1964) revealed a strong sense of personality disorders in the majority of the subjects examined. Consequently, records from the examination of a group of 100 persons were subjected to a detailed analysis in order to ascertain the following facts:

1. Personality types the subjects had represented before their Holocaust experience,

2. Convergence between the subjects’ opinion of their personality disorders and the results of an objective medical examination,

3. Characteristics of possible personality disorders,

4. Factors that should be associated with such disorders.

The problem of the psychological after-effects of the Holocaust experience has frequently been discussed and analysed. Gradually, researchers have ceased to concentrate on organic etiology and pathogenesis of personality disorders, and an interest in the psychological aspects of this problem has arisen. A view of the advocates for a limited base of personality disorders were presented in detail by Szymusik (1964). In due course, increasingly more publications appeared that emphasised the significance of psychological traumas in the development of predominantly long-term psychological after-effects of these catastrophic events. Eitinger (1961) stressed the importance of psychological factors in the etiology and pathogenesis of permanent long-term psychological disorders in former concentration camp prisoners. Bettelheim (1962) described Nazi ‘brain washing’ methods in detail, and quoted his own case as an example. Strauss (1957), among others, states that the majority of his patients suffer from chronic depressive reactions. He believes that the most important reactive factors in his group of patients comprise the following types of psychological traumas that result from the Holocaust experience: constant uncertainty, fear of extermination, and necessity to repress emotional reactions when witnessing acts of torture executed on relatives or friends. Frankl (1947), an existentially oriented psychiatrist, maintains that personality disorders are mainly due to such factors as the brutal devastation of human relations (such as deportations, or deaths of relatives and friends), loss of confidence in other people, and the necessity to stay with others all the time. According to Engel (1962), a representative of psychodynamics, the permanent suppression of revolt and aggression caused changes in the psychopathology of concentration camp survivors, which resulted in overwhelming depression.

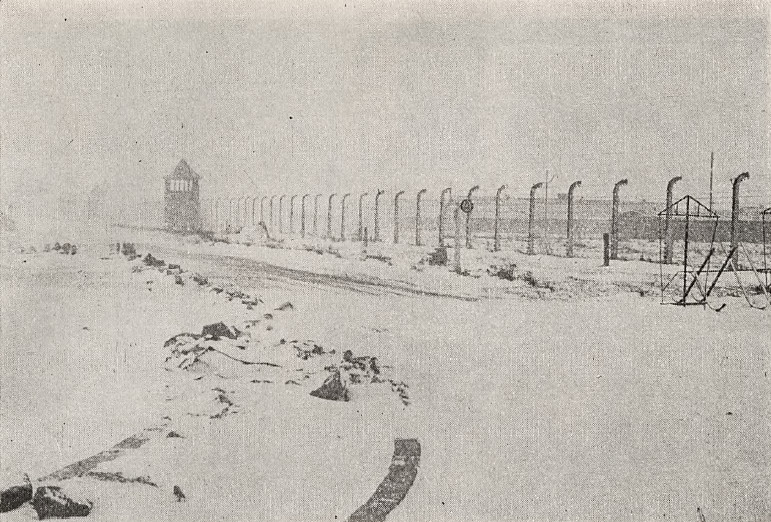

The Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp (27 January 1945)

Klein, Zellermeyer, and Shanan (1963) believe that such deep trauma as that experienced in concentration camps must lead to personality disorders, changes in self-perception, and disorders in the perception of the outside world.

The result of psychiatric investigation into the concentration camp experience were a reaction against classical views on psychological reaction, according to which even the most arduous experiences could not exert any permanent influence on the way an individual behaved and reacted unless a constitutional basis could be found in an individual. Both Venzlaff (1958) and Strauss (1957) maintain that the classical approach had to be changed in view of war experiences. Venzlaff (1958), as well as other authors, states that hard experiences may cause permanent personality changes of both a positive and a negative nature. Severe psychological trauma may be responsible for the development of new attitudes and a new value hierarchy as well as strengthening old attitudes and changing the approach to life in general. In various cases, the same traumatic factors may lead to personality disorders, or its stiffening and emasculating. Such disorders cannot be said to exceed the limits of the psychological norm, that is, they are not necessarily pathological (Venzlaff, 1958). The opinion that conventional psychiatric views on traumatic neuroses should be changed was also assumed by Baeyer (1961) and Matussek (1961). They accept the fact that concentration camp traumatic experiences are stronger and of a different nature than any other hitherto examined psychological trauma experienced by human beings. Therefore, the after-effects of the concentration camp should not be compared to the damage of any other psychological trauma (Matussek, 1961).

The basis of the present research work was both psychiatric and somatic examinations, with a special emphasis on neurological conditions. Whenever possible, both medical records and interviews were taken into consideration. A detailed description of the examination method, including the characteristic features of the examined group (concentration camp experiences), was discussed in other works (Orwid et al., 1964; Leśniak et al., 1978).

This paper can only present an attempt to discuss some aspects of methodological characteristics. These include an attempt to classify pre-camp personality types and post-camp personality disorders.

There appeared to be two alternatives that could possibly have been chosen: one was to accept an established typological classification and a method of defining various types used in a given taxonomic system; the other alternative was to ignore established classifications and search for a classification that would best reflect empirically observed events in the examined group.

A taxonomic system would result from a detailed analysis of the material. But the second alternative was accepted as, in this way, the risk of falsifying observed events – which might be caused by accepting the established pattern beforehand – could be diminished. Next, pre- and post- camp personality characteristics were registered according to the frequency of their occurrence with special attention paid to phrases used by the subjects themselves. In such a way, pre-camp personality characteristics and changes resulting from Holocaust experiences were specified and listed.

Numerous attempts were made to classify the data concerning the quantity and quality of pre-camp personality disorders. In effect, it resulted that the type and quality of given personality characteristics could best be embodied by a Jungian classification (Jung, 1950). It should be emphasised that this classification was not accepted beforehand but arrived at through an analysis of the data obtained by using open questions. That means the questions were not asked in view of any previously accepted typology of “normal personalities”.

The estimation of post-traumatic personality disorders, as well as defining pre-camp personality profiles, was based on opinions expressed by the subjects themselves. Whenever possible, data from case histories and interviews were taken into consideration along with objective analyses of post-camp ways of life (family conflicts, conflicts at work, behaviour codes,etc.). The possibility of direct medical observations of Holocaust survivors – greater than in the case of estimating pre-camp personality profiles – eliminated a subjective factor.

In many cases there were great differences in the intensity of personality disorders, thus, two main types of disorders were distinguished:

1. Post-camp personality disorders that are obvious but cannot be classified as pathological,

2. Post-camp personality disorders of a pathological type.

In the attempt to estimate pathological and non-pathological disorders, both medical and social criteria were considered. According to medical criteria, personality disorders were classified as pathological either if they had ever made the subject seek medical advice, or were based on direct medical observation. Social criteria were taken into consideration if the subject did not try to contact a psychiatrist in his post-camp period and was not clinically treated, though it was clear from an analysis of his lifestyle that experiences and new codes of behaviour had caused serious problems of adaptation to the environment.

Each individual was classified as a given pre-camp personality type and ascribed to a proper group of personality disorders. The classification was repeated several times over a long period. In order to verify the classification, a “competent judgement” method was applied which allowed only a small percentage (8 percent) of discrepancy between our own medical estimation and the judgement made by “experts”.

The next phase of the investigation included the preparation of collective tables for specified groups of personality disorders. The tables, which are not presented in this paper for technical reasons, comprise indispensable data for a statistical analysis of the material.

The examined group consisted of 70 male and 30 female subjects. Seventy persons in this group were incarcerated in the concentration camp between 20 and 40 years of age. Three occupational groups were established: manual workers (44 subjects), white-collar workers (38 subjects), and highly qualified white-collar workers (18 subjects). Forty subjects had primary education, 39 had secondary, and 21 higher; 76 subjects were imprisoned for political reasons (participation in conspiracy, independent action against the occupiers, etc.), 19 were imprisoned incidentally (in street roundups, as hostages, etc.), five for racial reasons (Jewish origin). One subject spent less than a year in the concentration camp; 5 subjects spent from one to two years, 27 subjects spent from two to three years, and 67 subjects spent from three to five years. The average period of incarceration in the concentration camp was calculated with a weighted mean at 3.4 years.

The first step in analysing data concerning the pre-camp personality profiles of the subjects was to establish what personality characteristics were mentioned most often by the subjects themselves. Subjects mentioned a total of 29 characteristic features of their pre-camp personalities (numbers in brackets refer to the number of subjects who mentioned a given feature): sociability (67), cheerfulness (47), calmness and self-control (41), energy (26), cheerfulness (24), religiousness (24), sincerity (22), frankness (22), sporting activities (22), resourcefulness and caution (21), mobility (15), diligence (15), social acceptance (13), unsociability (12), slowness (11), irritability (8), vehemence (8), ambition (8), confidence in others (7), honesty (7), domesticity (7), passivity (7), resistance (6), sensitivity (4), inclination to dominate (3), naiveté (3), reservedness (3), vivid imagination (3), thrift (3).

A detailed analysis of the above-mentioned features and the records from the examination of the concentration camp survivors indicate that the 100-person group included 73 extroverted and 27 introverted subjects (according to the Jungian classification).

Since the estimation of psychological trauma, as many authors state, is very difficult, we concentrated on stress of both a somatic and emotional character, which are more easily definable. They include:

1. Heavy somatic traumas, especially to the head, accompanied with the loss of consciousness.

2. Serious and difficult infectious diseases such as typhus fever, malarial fever, dysentery, or others.

3. Serious psychological stress such as danger of being exterminated, anxiety, humiliation, or selection.

Although post-traumatic stress was not taken into consideration when attempting the correlation, its great importance in the origin and development of psychological disorders was fully appreciated when the psychiatric estimation of subjects was performed.

Medical examination aimed both at defining the intensity of post-traumatic somatic and psychological trauma and at specifying personality changes induced by such traumas.

The attempt to specify the frequency of occurrence of a given characteristic feature was the first step in analysing post-traumatic personality disorders. There were 32 characteristic features (numbers in brackets represent the number of subjects that mentioned a given feature): irritability (41), problems with establishing contact with others (39), suspicion towards others (30), anxiety (31), apathy (27), tearfulness (18), inability to appreciate material values (15), underestimating other people (18), a feeling of the senselessness of life (14), greater tolerance towards others (13), bitterness (13), conflict with one’s environment (12), appropriate estimation of others (9), subjective positive estimation of traumatic experiences (8), indifference to the misfortune of others (8), living from day to day (8), great importance of moral values (8), restlessness (7), pessimism (6), increased religiousness (6), inferiority complex (6), greater bravery (6), desire to make the most of life (4), lack of fear of death (4), increased life energy (4), emphasis on ethical problems (3), breakdowns (3), memory deterioration (3), stronger self-dependence (3), preoccupation with health problems (3), increased activity (3), cynicism (3).

As can be observed, the post-traumatic personality disorders were of various natures and their diffusion in the whole 100-person group was very wide. Therefore, they were classified according to conventional topical criteria. Certain authors have followed such a convention (e.g. Paul and Herberg, 1963) and do not divide personality disorders into specific groups but put special emphasis on their quality and frequency of occurrence. In such a way, the following classification of post-traumatic personality disorders in the 100-person group was arrived at:

1. A change in relationships with other people, either of a negative nature, as observed by the subjects themselves (avoiding other people, 39 subjects; suspicion, 30; under-estimating others, 18 subjects) or a positive nature (increased love for people, 9 subjects).

2. An altered attitude towards other people and the outside world – of a positive nature (increased tolerance 13 subjects; emphasis on moral and ethical values, 11; increased religiousness, 6), of an exaggeratedly positive nature (higher value for life, 4 subjects, overestimating material values, 4 subjects), of a negative nature (bitterness and pessimism, 19 subjects; aimless “living from day to day”, 22 subjects; cynicism, 3 subjects; lack of fear of death, 4 subjects).

3. Permanent character changes – of a negative nature (irritability, 41 subjects; tearfulness, 18; inferiority complex, 6; preoccupation with health problems, 3) and of a positive nature (increased bravery, 5 subjects; stronger self-dependence, 3 subjects; increased activity, 3 subjects).

After a consideration of the general nature of the post-traumatic stress disorders in concentration camp survivors, a detailed psychiatric analysis (qualitative and quantitative) was made, and all data obtained from the objective medical observation during the investigation was taken into consideration. Then, paying appropriate attention to the frequency of disorders as well as to their significance and impact on general psychological life, four groups (types) of personality disorders were specified. Group division was based on the character and intensity of given symptoms and features. Generally, the following personality groups were distinguished:

I. Depressive, 33 subjects.

II. Suspicious, 19 subjects.

III. Explosive, 16 subjects.

IV. Depressive-suspicious, 23 subjects.

Group V included nine subjects in which personality disorders were not found either by subjective or objective medical examination.

Subjects with “positive” aftereffects of the concentration camp experience appeared to comprise a separate group. As was later found, however, subjects who believed in a positive impact of the Holocaust experience might also be included in one of the previously mentioned groups of personality disorders, or in the group that did not experience such disorders at all.

Characteristics of the specified groups can be presented in the following way: The main criteria of classifying subjects as members of group I (depressive personality) were as follows: fixed moods of depression, general pessimistic attitudes combined with the belief that life was aimless, and tearfulness. Different sorts of anxiety, restlessness, bitterness, breakdowns, inferiority complexes, etc., were regarded as additional symptoms. Differences in the intensity of these symptoms never reached the level of psychotic disorders. On the other hand, their quality and intensity constituted a basis for classifying the subjects into the “pathological personality” group (16 subjects) or “non‑pathological personality” group (17 subjects) in the previously described sense.

Group I, of a depressive personality, was the most numerous: 33 subjects (22 males and 11 females). Not all subjects with symptoms of depression were included in this group since depression was also characteristic of group IV and was placed there alongside suspicion. Thus, depression characterised 56 subjects altogether, which makes more than half of all subjects. This observation is consistent with statements made by the majority of authors (e.g. Paul and Herberg, 1963; Strauss, 1957) who claim that depressive neurotic symptoms are dominant in the concept of long-term aftereffects of the Holocaust experience.

Manual workers with primary education statistically significantly dominated the depressive personality group. They were usually imprisoned for political reasons. Their average age on imprisonment was 31 years, the same as the general mean value.

The following is an example of post-traumatic personality disorders of the depressive nature.

A.J. (record no. 3/L), a craftsman with primary education, married, imprisoned at the age of 34 during a street roundup in 1940. Before incarceration, he had been quiet, self-controlled, cheerful, sociable, honest, open, and trustful towards others. The analysis of his pre-camp lifestyle pointed to a good and normal family atmosphere. He married at the age of 33 and his family situation was changeable. Generally, he did not have any serious health problems besides a difficult case of angina at the age of 24. He was imprisoned for five years. In the concentration camp in 1942, he underwent an operation for appendicitis. In 1944, he was heavily beaten by a prisoner-overseer who hit him on the head with a stick. Since that time, A. J. has often suffered from a buzzing in the ears that intensifies when he bends down or has a higher temperature. Concentration camp experiences led him to the Muselmann state. He experienced a complete loss of energy, and was constantly tired. In 1945, he returned home and when he learnt that his wife had been unfaithful to him, he divorced her. After a year, he remarried. The first five years of his second marriage was a happy period for both him and his wife. Afterwards, however, they often argued and his wife claimed that he did not take proper care of her. Since the time of his incarceration, A.J. has constantly been depressed, restless, and irritable. Those with contact with him noticed that A.J.’s character underwent a significant change in comparison with the pre-camp period. Medical examination resulted in the discovery of a 6 cm long scar on the cranial vault, which was painful when touched. Since 1954, he has been under neurological observation because of a backache, from which he has suffered since the time of the assault. In 1959, he became a disability pensioner. He was classified as a member of the depressive personality group because of both medical consideration and competent judgement method. The symptoms were very clear, permanent and very intense, which meant that they were pathological.

The following are the main symptoms, based on which subjects were classified as members of group II (suspicious personality): suspicion towards others, shunning relations with other people, significantly more problems in establishing contact with others, and distrust. Additionally, underestimating others, anxiety, a high tendency to conflict with one’s environment because of the personality features mentioned above, and a distinct sense of being wronged were also taken into consideration.

The suspicious personality group included 19 subjects (13 males and 6 females). Symptoms characteristic for this group were also recorded in group IV, in addition to depression in 42 subjects. It was obvious that the Holocaust experience led to mistrust and suspicion towards other people in the majority of survivors. The suspicious personality group mainly consisted of white-collar workers with secondary education. The average age at the time of imprisonment was 33 years, more than the general mean value. Also, different arbitrary causes of incarceration were statistically dominant in this group. The average period of incarceration in this group was 3.3 years, slightly shorter than the general mean value of 3.4 years.

The following is an example illustrating personality disorders in the suspicious personality group:

A white-collar worker (record no. 20/L), imprisoned in 1941, at the age of 31, for political reasons. Before imprisonment, she was sociable, energetic, cheerful, and popular among relatives and friends. She trusted other people, had artistic interests, and was patriotic. She adapted to camp conditions after a year of incarceration. However, she never managed to lose the fear of death and thoughts of suicide. In her own opinion, she managed to survive due to an intense desire to witness Nazi defeat, to live in an independent Poland, and her strong religious faith. During her incarceration, she suffered from an illness accompanied by high fever. When she returned home, she could not work professionally for a year, and during that period, she underwent medical treatment. Since 1946, she has worked in her profession. Since the time she left the concentration camp she has changed significantly: she has lost confidence in other people and now is afraid of them, and she is scared by the necessity of establishing new contacts: “When I am among people I feel as if I were left naked among wolves”. She has become suspicious, which is the reason for many conflicts with her environment. She confides only in former Nazi concentration camp prisoners. Other people scare her and she tries to limit her contact with them. She feels she is above their understanding: “I think people are wicked and heartless.” She is restless, excitable, and suffers from sleep disturbances. Already before incarceration, medical examination revealed neuropathic aspects of her personality. This, however, did not have any negative influence on either her private and professional life, or her social status. Suspicion and loss of confidence came after the Holocaust period and led to many conflicts with her environment. Moreover, she began to suffer from general asthenia, which was often accompanied by depressive moods and emotional tension. She did not suffer from any strong somatic trauma during her incarceration. Despite this, however, her personality changes were medically classified as pathological.

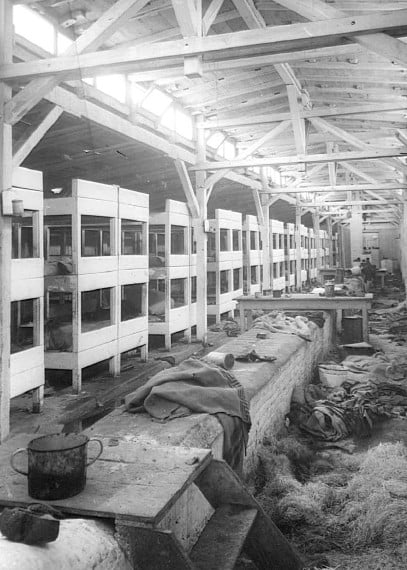

Barracks at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Photograph by A. Kaczkowski

The main criteria for classifying subjects into group III (explosive personality) were as follows: irritability, explosiveness, and restlessness. Such symptoms often resulted in conflicts with one’s environment (in family, at work). Moreover, excessive emotional reactions to even unimportant stimuli, greater self-confidence, self-dependence, and energy as well as a cynical attitude to life were also observed.

The explosive personality group comprised 16 subjects, including 14 males and 2 females. It might be assumed that in this case, post-traumatic stress disorders were conditioned by the relatively young age of the subjects at the time of their incarceration – 27 years, which was the lowest average age of all groups. This observation differs from the one made by some other authors (e.g. Paul, Herberg, 1963; Strauss, 1957) who emphasise paranoia inclination and frequent cases of infringing the law by individuals imprisoned in concentration camps in their younger days. It should be added, however, that all such observations were based on larger material and the age of imprisonment was often much lower than in the group of explosive personality types discussed here. This group included mainly individuals with higher education, usually imprisoned for political reasons and with an average of 3.4 years of incarceration.

The following example illustrates personality disorders characteristic for explosive personalities:

A man with higher education (record no. 16/M), was one of five children, developed normally in his childhood, was a good pupil, and never suffered from any serious diseases. He was a cheerful, sociable, energetic, and popular man, actively interested in sport and technology. He married on the first day of the war, then took part in the September campaign, and worked professionally. In 1942, when he was 35, he was arrested by the Gestapo because he had been denounced as a saboteur by a Volksdeutsch. He spent three months in prison where he was frequently beaten and tortured. Despite the fact he never admitted having done what he was accused of, he spent the rest of the war in a concentration camp. He was incarcerated in Auschwitz and then Buchenwald. He went through difficult psychological and physical experiences, had a strong fear of death, witnessed the execution of 250 prisoners, several times suffered from pneumonia, pleurisy, and typhus fever, and was frequently beaten. In his opinion, he managed to survive due to the help of his fellow prisoners, positive examples of heroism, and his religious faith. After the end of his incarceration, he quickly managed to return to Poland without any help, found his wife and a daughter and began professional work again. As he himself and those around him noticed, he changed a lot: he became very explosive, irritable, and even attacked people when very angry. He became fond of home-life and was easily tired by wider company. He could not help making unpleasant remarks to his superiors, even though he knew that he was acting against himself. An objective analysis of his post-camp life revealed that he often changed work because of many conflicts with his environment. Somatic examinations revealed arterial hypertension. His pre-camp personality was medically classified as extrovert. Somatic stress in the Holocaust period (traumas and infectious diseases) was defined as serious and his post-traumatic personality disorders as pathological.

Group IV (depressive and suspicious personality) included subjects with personality disorders that were the basis for classifying them in both group I (depressive personality), and group II (suspicious personality). This group consisted of 23 subjects (14 males and 9 females). Their average age at the time of imprisonment was 34 years, the highest of all groups. Statistically essential was the fact that subjects with secondary education, white-collar workers, imprisoned mainly for political reasons or because of their Jewish origin, constituted the majority of the group. The analyses of group I (depressive personality) and group IV (suspicious and depressive personality) point to the fact that symptoms of depression and suspicion could be found in individuals who were older than other subjects at the time of their internment.

The following is an example of personality disorders characteristic for group IV:

A manual worker with primary education (record no. 4/L), developed normally, a good pupil, never suffered from any serious illnesses except for appendicitis. She was cheerful, nice, sociable, sincere, open, honest, religious, sentimental, and sensitive though she never used to worry for a long time. In 1942, she was caught during a street roundup and after two months of imprisonment, she was incarcerated in Auschwitz-Birkenau where she spent three years. During her incarceration, she had a constant fear of death. She was selected for extermination many times and always managed to escape death due to the help of others. She showed great emotional tension and cried every time she talked about these experiences.

Her most unpleasant recollections of the Holocaust were being forced to carry corpses, a deadly fear at the sight of a Nazi, and constant fear of becoming a Holocaust victim. For three months, she suffered from abdominal fever, then from malarial fever, and often lost consciousness. She was exhausted and suffered from starvation swelling. Her weight was 36 kg when she left the camp. During incarceration, she was hit with a stick on the head by an SS-man and since then she has suffered from frequent headaches and vertigo as well as from body-balance disturbances. In her own opinion, she managed to survive due to “fate, religion, faith, and the help of campmates.” She believes she never adapted to camp conditions. She had a strong desire for revenge although she did nothing at liberation. For several months after liberation, she did not feel well, suffered from insomnia, then “somehow I managed to adapt.” Since the Holocaust period, she has lost confidence in other people, she does not trust them anymore, and she is generally more suspicious: “It seems to me that people are wicked and unfriendly.” Further, she is constantly depressed, “she lost her cheerfulness.” She talks about her Holocaust experience very reluctantly, and often pretends that she does not remember past experiences. She is frequently anxious in her dreams, which bring reminders of the Holocaust: “The same situations are repeated in my dreams - I am selected for extermination, to be burnt.” When she meets other Holocaust survivors she tries to talk about something else because “[W]henever I talk about the concentration camp, I have horrible dreams afterwards, I become sad, I cry, or rather, I cannot help crying.” She has become less communicative, avoids people, cannot sleep properly, and can be woken easily. Regarding somatic aspects, an objective medical examination pointed to pressure sensitivity in the left supratemporal area with decreased touch and pain perception, which, in the subject’s opinion, were caused by the traumatic experience in the camp. Her right pupil was slightly irregular but both pupils reacted to light and convergence. In the area of the right hypochondrium, tenderness to pressure was also observed. Emotionally the subject showed suspiciousness, periods of depression, and often cried when she talked about the Holocaust.

Group V (subjective and objective lack of personality disorders) includes nine subjects (6 males and 3 females) who could not be classified in any of the aforementioned groups. Nine subjects did not suffer from any personality disorders and this fact was confirmed both by subjective opinion and by objective medical examination. The majority of this group were subjects with higher education, including seven persons who were imprisoned for political reasons. Despite the fact that their average period of imprisonment was the longest (3.8 years) and six of them were subjected to severe somatic traumas and stress similar to those discussed in other groups, members of this group did not show any personality disorders, as was confirmed by their own opinion. It may be assumed that the controlled social and patriotic attitudes of these subjects, which were expressed in their underground activities, made the members of this group more resistant to the camp conditions.

The following is an example illustrating lack of personality disorder:

A woman with higher education (record no. HIT), developed normally with a happy and cheerful childhood. Before incarceration, she had suffered only from standard childhood diseases (measles, scarlet fever) with typical course. At school, she was a good pupil and after graduation, she worked professionally. Cheerful, friendly, witty, sociable, sensitive, sincere, and open, she easily made contact with others. In the autumn of 1941, she was imprisoned for political reasons at the age of 23. After several months of imprisonment, she was transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp where she was incarcerated until the end of the war. The Holocaust period was especially difficult for her since she was aware that her parents were also incarcerated. In the spring of 1943, her mother was exterminated. In her own opinion, she managed to survive due to friendly and helpful campmates and the conviction that she was indispensable for her family. She suffered most because of the permanent imprisonment with other people. After liberation, she rested for a couple of months, went back to her professional work, and was promoted. She travelled a lot. In the initial period after her liberation, it was difficult for her to establish contact with people who had not lived through the Holocaust. She could not understand the troubles and worries of others. Gradually, however, she managed to adapt to the life of her environment. As she herself states, she feels well both psychologically and physically after living through the Holocaust. She does not think the concentration camp experience caused any permanent changes to her personality. An objective medical examination based on both pre- and post-camp personality analysis as well as the data obtained from direct observation made during the examination allow for the assumption that the subject is a self-controlled, cheerful, psychologically resistant person without any personality changes that might have resulted from her Holocaust experience.

The examples described above illustrate the cases of all 100 subjects in groups I to V. In the course of examination, it turned out that some of the respondents felt subjectively that the incarceration period had a positive impact on their personalities. Since I had never met a description of such a group in international literature, I gave it my special attention.

An abandoned wooden barrack at Auschwitz-Birkenau after liberation, 1945

Concentration camp survivors estimating their Holocaust experience “positively” claimed that they did not notice any negative changes in psychological or physical spheres. Although several subjects admitted that they still suffered from various negative consequences of the Holocaust, they maintained that the positive influence of the concentration camp experience was much more important. The positive influence, in their opinion, was mainly that they were able to know themselves and other people better, that their attitude towards the outside world had become much more definite, that they became hardened, and established deep-rooted relationships with others, which had been impossible before their incarceration. Some of them lost neurotic problems that had made their life difficult in society, such as uncertainty, inferiority complexes, timidity and shyness, and the inclination to shrink into oneself. In one case, the positive estimation of the Holocaust period was based on clearly psychotic experiences. This was the case of a woman who was taken ill with a schizophrenic type reaction and the following psychotic symptoms can still be observed in her personality: delusions, hallucinations and general unusual behaviour. She believed that she was incarcerated in a concentration camp according to God’s will, in order to strengthen her religious faith. And, she believed, such was the case. As many subjects stated, difficult concentration camp conditions gave all of them a chance to test their positive reactions in difficult situations. It should also be taken into consideration that it might be difficult for some individuals to accept the fact that they may suffer from various personality disorders. Despite the fact that eight subjects (five males and three females) understood the influence of the Holocaust on their personality in such a way, objective personality disorders were recorded in five of them, and they could be classified into the appropriate groups. The remaining three subjects were qualified for group V (no personality disorders). This is why we did not feel group VI, that is, individuals with a positive influence from the Holocaust, should be treated separately.

The following is an example illustrating the personality profile of a subject who subjectively estimated the influence of the Holocaust as positive:

A man with higher education (record no. T/4), works professionally. His pre-camp personality was psychasthenic. He was shy and hesitant, had a permanent sense of guilt, and an inferiority complex. He was imprisoned at the age of 33 and after a long time spent in prison was incarcerated in Auschwitz, where he was interned until liberation. During incarceration, he was severely beaten twice and had a heart attack, with the sensation of dying. In Auschwitz, he suffered most from sleep disturbances, thirst, and from the existence of a hierarchy between older and younger prisoners. In his opinion, he survived due to the help of his fellow prisoners, favouritism, and religious faith. Before liberation, during bombardment, he was buried alive in rubble and his backbone was injured. Soon after liberation, he started professional work.

When asked about the influence of the Holocaust experience on his personality, he stated: “I learnt to think, my personality became crystallised, I became intellectually mature.” He maintains that his incarceration in the concentration camp resulted in the enrichment of his spiritual life, as well as in making him more tolerant and understanding towards other people. He no longer suffers from a sense of guilt, and left the concentration camp with the conviction that people were righteous. He managed to lose both shyness and embarrassment towards other people, fear, and complexes; he became calmer, less irritable, and more self-confident. He believes that his Holocaust experience was positive: “That period led to the crystallisation of my own self, I found my place in the world, in life, and in my times.” An objective medical analysis suggested that the subject’s pre-camp personality was of a psychasthenic type. The analysis of his post-camp way of life, as well as observation during the examination, clearly shows that the symptoms characteristic for psychasthenia were much weaker: the subject had, in fact, fewer problems with establishing contacts with others, and became more self-confident. However, such symptoms as twitching and obsessions are still present, although the subject himself either does not notice or does not pay any attention to them. He has managed to adapt to the necessities of social, family, and professional life.

This case was a member of group V (no personality disorders).

After a detailed psychiatric analysis and remarks on particular groups (I – V), I would like to sketch general characteristics that include a clinical estimation and statistical correlation within each group as well as among different groups.

The majority of the group of 100 persons were male subjects (70), there were only 30 women in the group. In groups I, II and III, female subjects constituted one-third of the whole number. In the remaining groups (III and V), female subjects were much more outnumbered. Statistical analysis revealed that the gender factor was essential in the characteristics of particular groups. For statistical calculations chi-square was used with p = 0.05. Table chi-square was 0.488, calculated chi-square was 4.23. Thus, no statistical significance was found, which means that, as far as gender was regarded, the distribution of subjects in particular groups were uniform.

The average age on imprisonment was 31. In group I (depressive personality) and group V (no personality disorders) the average age at the time of imprisonment was the same as the general mean value in the whole group. The average age in groups II (suspicious personality) and IV (suspicious and depressive personality) was much higher that the general mean value, and in group III (explosive personality) the average age was the lowest.

Concerning the distribution of different professions, in group I manual workers were most important statistically, in groups II and IV white-collar workers, and in groups III and V highly qualified white-collar workers. The calculated chi-square was 16.24, and table chi-square at the confidence level of p = 0.05 was 15.507.

Attention should be paid to the consistency between this distribution and the distribution of education levels: in group I subjects with primary education constituted the majority, in groups II and IV it was subjects with secondary education, and in the remaining groups it was subjects with higher education.

The following distribution of different causes of imprisonment could be observed: taking the proportion of all groups into consideration, in group I, the majority of subjects were arrested for political reasons, and the minority arbitrarily, or because of Jewish origin. This observation is consistent with statistical calculation, which points to the significance of political reasons of imprisonment in this group: with p = 0.05 calculated chi-square =15.93, table chi-square =15.507. In group II chance and Jewish origin were most significant, and in groups III and IV, political reasons. In group V, seven subjects out of nine were imprisoned for political reasons.

The average period of incarceration was the same in groups II, III, and IV (3.3). In groups I and V it was higher than the general mean value: in group I it was 3.6 and in group V it was 3.5 years. However, if we excluded from group V a person who spent less than a year in the concentration camp, the mean value for group V would be 3.8, which would be the highest of all groups.

Both personal observations and statistical calculations indicate that “extroversion” and “introversion” were not significant for post-traumatic personality disorders.

Severe traumatic experience was common to 33 subjects, and 21 suffered from infectious diseases. The remaining subjects — 18 in number — did not suffer from severe somatic stress during their incarceration.

Considering all the above criteria, post-camp personality disorders were defined as pathological in 45 subjects, and as non-pathological in 46 subjects. Statistical calculations made with the help of chi-square did not indicate any significance of somatic stress in classifying subjects in particular groups. The same can be said about the estimation of pathological and non-pathological disorders.

Statistical analysis did not suggest any correlation between post-camp personality disorders and the intensity of somatic stress. Eighteen subjects did not suffer from such trauma although personality disorders were observed in 15 of them, in 4 cases qualified as pathological and in 11 as non-pathological. It might sometimes happen that severe traumatic stress did not result in any visible personality changes (in 6 cases) or that such cases were noticed though not qualified as pathological (in 46 cases).

Evaluating the results of these analyses, it should be stated that both the observations made by the subjects themselves and the objective psychiatric examinations point to the fact that 91 out of 100 subjects, former prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, still suffer from personality disorders that result from their Holocaust experience. The disorders were widely discussed and various psychological and somatic reasons were included in the descriptions. Primary significance in the origin and concept of post-camp personality changes was ascribed neither to the negative influence of somatic stress nor to the impact of emotional shock.

The three main types of personality disorders – depression, suspicion, and explosiveness – may lead to certain analogies; namely, as is well known from psychiatric experience, acute phases of certain psychological illnesses frequently resulting in the same types of disorders, though they are usually of a much stronger nature.

The question is, do the three types of personality disorders represent a general tendency of personality development after experiences that exceed the limits of human endurance?

Translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1965.

References

1. Baeyer W. Erlebnisbedingte Verfolgungsschäden. Der Nervenarzt. 1961;32: 534-538.2. Bettelheim B. The Informed Heart: Autonomy in a Mass Age. New York: Free Press of Glencoe; 1962: 118-126.

3. Eitinger L. Concentration Camp Survivors in the Postwar World. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1962;32: 367-375.

4. Eitinger L. Pathology of Concentration Camp Syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;7: 371-379.

5. Engel W.H. Reflections on the Psychiatric Consequences of Persecution (An Evaluation of Restitution Claiments). American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1962;16: 191-203.

6. Frankl V. Ein Psycholog erlebt das Konzentrationslager. Vienna; 1947.

7. Jung C.G. Psychologische Typen. Zurich; 1950.

8. Klein H., Zellmeyer J., and Shanan J. Former Concentration Camp Prisoners on a Psychiatric Ward. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1963: 334-342.

9. Leśniak R. Poobozowe zmiany osobowości byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Translated as “Post-camp Personality Alterations in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1963;22: 13-20.

10. Leśniak R., Mitarski 1, Orwid M., Szymusik A., Teutsch A. Niektóre zagadnienia psychiatryczne obozu w Oświęcimiu w świetle własnych badań. II doniesienie wstępne [Some psychiatric aspects of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp in the light of personal research: 2nd preliminary report]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1961;18: 64-73.

11. Leśniak R., Orwid M., and Teutsch A. Untersuchungen an ehemaligen Häftlingen der KZ Auschwitz-Birkenau durchgeführt an der Psychiatrischen Klinik der Medizinischen Akademie in Kraków (1959-1976), [according to Bogusz J., and Jagoda Z]. VI International Medical Congress of FIR (Prague, 30.11 – 2.12.1976). Przegląd Lekarski. 1978;35: 228.

12. Matussek P. Die Konzentrationslagerhaft als Belastungssituation. Der Nervenarzt. 1961;32: 538-542.

13. Orwid M. Socjo-psychiatryczne następstwa pobytu w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim-Brzezinka [Socio-psychiatric aftereffects of the Auschwitz- Birkenau Concentration Camp’]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 21: 17-23.

14. Orwid M., Szymusik A., Teutsch A. Cel i metoda badań psychiatrycznych byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu [Purpose and method of psychiatric examination of former prisoners of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 9-11.

15. Paul H., Herberg H.J. Psychiatrische Spatschäden nach politischer Verfolgung. New York and Basel: Karger S.; 1963.

16. Strauss H. Besonderheiten der nichtpsychotischen seelischen Störungen bei Opfern der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung und ihre Bedeutung bei der Begutachtung. Der Nervenarzt. 1957;28: 344.

17. Szymusik A. Astenia poobozowa u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu. Translated as “Progressive Asthenia in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 23-29.

18. Teutsch A. Reakcje psychiczne w trakcie działania psychofizycznego stressu [stresu] u 100 byłych więźniów w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu-Brzezinka. Translated as “Psychological Reactions to Psychosomatic Stress in 100 Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 12-17.

19. Venzlaff U. Die psychoreaktiven Störungen nach entschädigungspflichtigen Ereignissen. Berlin; 1958.