Author

Wanda Półtawska, MD, PhD, born 1921, psychiatrist, Professor Emerita of the Chair of Psychiatry at the Kraków Medical Academy. Formerly Director of the Institute of the Theology of the Family at the Kraków Pontifical Academy of Theology. Ravensbrück survivor, No. 7709.

Introduction

In 1974-1976, former prisoners were examined for disability certification purposes. Since the new pension act allowed some former prisoners to qualify for the group of disabled soldiers, the purpose of the examination carried out 30 years after the war was to reveal the long-lasting effects of the concentration camp experience. One hundred and fifty former concentration camp prisoners (75 men and 75 women), in the majority of cases imprisoned in Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, were the subjects of the examination. Some of the subjects were imprisoned in several different camps. The length of the period spent in the camp ranged from half a year to almost five years, and the average time spent in the camp was two and a half years. The examination resulted in diagnosing the “KZ‑Syndrome” of a varying intensity and different clinical manifestation in all the subjects, and all of them were qualified as war invalids. None of the subjects proved to be healthy. Although some of them still work professionally, all exhibit pathological symptoms and disability awareness.

Psychiatric examinations revealed a variety of symptoms that made the diagnosis even more difficult. Many different pathological units could be observed in one person. Special attention was paid to the so-called “Targowla Syndrome”, which appeared to be especially characteristic for KZ-Syndrome. Although the classical Targowla Syndrome was observed only in subjects with a large number of progressive asthenia symptoms, some traces of this syndrome were present in all subjects.

Clinical manifestation

Psychopathological symptoms of various types were found in all the subjects. In some cases, at the beginning of the examination, the subjects claimed that they could observe no symptoms at all and it was only during conversations, once good interpersonal contact had been established and the subjects had become more open, that they admitted increasingly numerous ailments.

Characteristically a great variety of symptoms were revealed. In some cases, the following symptoms were present simultaneously: chronic depression, encephalopathic disorders, symptoms characteristic for progressive asthenia, and psycho-organic syndrome. In such a situation, classification into different diagnostic groups appeared to be impossible and therefore introduction of the term KZ-Syndrome appeared appropriate, as it might include the whole variety of symptoms.

In order to facilitate the analysis, however, three diagnostic groups were distinguished: a) chronic depression; b) progressive asthenia; and c) psycho-organic syndrome. It should be emphasised again that each group included a variety of symptoms. The subjects were classified in a given group based on the dominant symptoms they represented. The majority of authors emphasise five destructive factors in camp life; starvation, fear, cold, lack of air, and mechanical traumas, especially skull injuries. Based on clinical manifestations, it would be impossible to state exactly which symptoms were the results of starvation disease, and which were caused by other factors. Moreover, clinical manifestations were even more complex because of the process of ageing. It had already been proved that the former prisoners aged quicker than other people, and that they died earlier, as statistical data suggested.

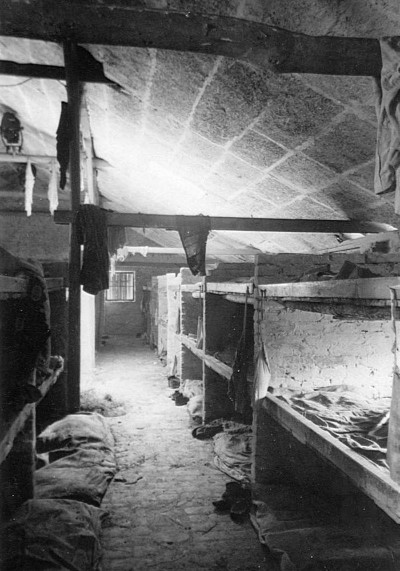

An abandoned brickwork block at Auschwitz after liberation, 1945

The process of ageing was characterised by typical defects of memory, which led to particularly distinct paroxysms of hypermnesia. In comparison with examinations made 15 years ago (an article on the so-called “Auschwitz children” in Przegląd Lekarski, 1967;24: 89), the present paroxysms of hypermnesia, especially in elderly people, were connected with affective insufficiency and a tendency to be loquacious. Stronger emotional reactions and an increasing sense of having been wronged could also be observed. Symptoms of depression appeared alongside with the decrease of physical strength and increased tiredness. Camp recollections could not be eliminated from the memory of the former prisoners and appeared increasingly frequently, accompanied by the need to discuss the events of that period. Whenever camp stories were told, strong emotional reactions could be observed, the subjects cried, felt uneasy; and still manifested reactions of anxiety.

The process of ageing is always accompanied by a lower immunity level, and an increased tendency to tire easily, which is related to paroxysmal hypermnesia states. Consequently, the fact that such states become increasingly more intense with time results in a sense of increased disability. The former prisoners usually gave up medical treatment at that point, as they became convinced that their ailments were incurable. Although in the majority of the cases, they had tried to obtain some medical advice earlier, at some point they gave up all hope of improving their health and became convinced of the hopelessness of their situation. This, in turn, led to a feeling of bitterness. They felt different, not understood, and increasingly lonely. As a result, states of depression could be observed in all examined persons with different degrees of intensity. The decision to give up medical help was usually followed by an attempt to find a remedy on one’s own; thus, different defensive mechanisms that corresponded to different dominant symptoms could be observed at that stage.

As was stated above, all subjects were divided into three diagnostic groups.

1. Chronic depression.

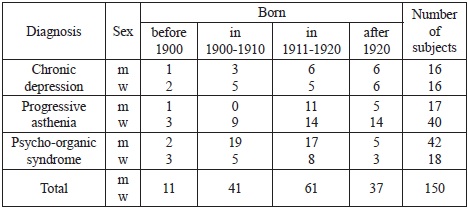

Thirty-two subjects of different ages were classified in this group (equal numbers of men and women). The group included some subjects who were born after 1920. No correlation could be found between clinical manifestation and age. It was astonishing, however, that this group included 21 subjects who spent more than two years in the camp, and only three subjects a year or less (cf. Table I). Sixteen men who qualified for this group, in addition to their states of depression, also exhibited psycho-organic symptoms. Similarly, 13 women from this group suffered from symptoms of nervous system injury. Despite this, however, they were placed in the group of chronic depression since symptoms of depression were dominant in their clinical manifestations.

Table I: Age of the subjects

All the subjects were fully aware that they were not able to find any reason for their states of depression and that they had lost their joy of life. They were convinced, however, that those symptoms were connected with their camp experiences. Some of them stated, “something broke down inside me” or “my nervous system is damaged”. They were less active and were not able to establish contact with others. They never spoke about their problems and thus others might not be aware of their state. The majority of the former prisoners suffered from insomnia and often remembered the camp period during their sleepless nights.

Hypermnesia did not appear in paroxysms, in its classical form described by Targowla, but the former prisoners who suffered from it were in permanent states of depression in which they experienced “compulsory” memories of the camp. Hence, such a situation might be referred to as a state of hypermnesia, and not as a paroxysmal hypermnesia. At the same time, subjects could be described as deprived of defensive mechanisms. They described their states in the following way: “This is not real life but vegetation. One forces his way through it and waits for the end of it”. They felt unable both to perform professional work and to cope with life in general. Helplessness, hopelessness, and bitterness were dominant characteristics of their condition. It should be stressed that no pharmacological means could help in such cases.

2. Progressive asthenia

The group comprised 57 subjects with a majority of women (40 women and 17 men). In general, progressive asthenia appeared to be more frequent in women than in men. It was also characteristic that this syndrome appeared in younger people (Table I).

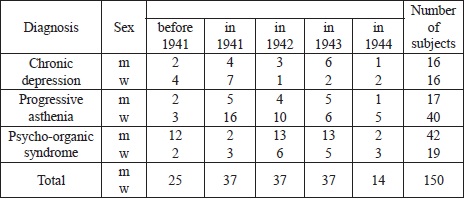

Regarding the period spent in the camp, the subjects from this group usually spent a long time in the camp, (more than three years; cf. Table II). Periodic states of depression could be observed in the men.

Table II: Length of the stay in camp

All the subjects placed in this group, that is, with a diagnosis of progressive asthenia, were aware of their psychological disorders and were convinced that “they were not quite normal”. In such cases, the states of paroxysmal hypermnesia had their full classical form. They consisted of symptoms of tiredness and could be caused by various associated factors. As it is already known, a paroxysm of hypermnesia consists in the pressure of recollections, which do not appear as thoughts but as a sequence of very vivid scenes of events that happened in the past. The recollections are accompanied by a number of vegetative symptoms such as trembling, becoming pale, tachycardia, sweating, and others. From the psychiatric perspective, anxiety states should also be mentioned. Such paroxysms usually come at night and are preceded by anxiety dreams. To some degree, they are similar to symptoms of an epileptic type. Some of the subjects exhibited epileptic symptoms. All such subjects were aware of the irrationality of their experiences. Earlier they had asked for medical advice, and psychopharmacological means were used in the majority of cases. Such treatment, however, proved to be unsuccessful and most of the subjects gave it up. Later, they tried to hide their symptoms and those around them were usually ignorant of their problems, especially due to the fact that the subjects also had generally good periods.

Most frequently, a sudden breakdown came unexpectedly, which might explain the changeability of pathological symptoms. With time, the states of bad mood appeared increasingly often and physical strength continually lessened. The usual reaction of self-defence was an attempt at a conscious reflection on the irrationality of the experiences and excessive activities undertaken in order to forget about unpleasant experiences. The states of increased activity, however, led to total exhaustion, which, in turn, resulted in paroxysmal states of depression. Over time, periods of excessive activity became shorter and periods of depression longer. It resulted in inability to work systematically, and the need to rest longer and more frequently.

In light of the foregoing research, it may be stated that the progressive asthenia syndrome should be viewed as a result of starvation disease and excessive psychological trauma. This can explain the fact that the progressive asthenia group included the majority of subjects who spent a long time in the camp where they suffered from starvation. This can also account for the fact that the majority of women in this group were psychologically more sensitive than men.

3. Psycho-organic syndrome

The group comprised 61 subjects with a majority of men (42 men, 19 women). If we consider the fact that there were 14 men in group I who also manifested the symptoms of the psycho-organic syndrome, then we may assume that this syndrome is more frequent in men that in women. This observation is consistent with the experience of general medicine, which points out that men age earlier than women and that premature senility can frequently be observed in former concentration camp prisoners. This phenomenon is most probably connected with cranial injuries. Based on the material collected we may state that men were more frequently exposed to head traumas than women, both during prison examinations and during their time in the camp. Therefore, they more frequently suffered from the symptoms of organic injuries of the central nervous system. Moreover, they also exhibited symptoms of premature senility in the form of symptoms of apathy, affective insufficiency, and defective memory.

In the majority of such cases, states of depression appeared alongside a dominant sense of having been wronged. The subjects represented an attitude of complaint, which was sometimes accompanied by lowered self-criticism. Some of them developed a feeling of rancour towards the whole world. Regarding Targowla Syndrome, its typical form could not be found among the members of this group. Although paroxysms of hypermnesia were quite frequent, they were not accompanied by affective insufficiency. The subjects would burst into tears, were easily deeply moved, could not help talking about their experiences, constantly returned to camp recollections, which made them intolerable to others. The impression was that they would never be able to break free of their recollections. This talkativeness should be interpreted as one of the defensive mechanisms.

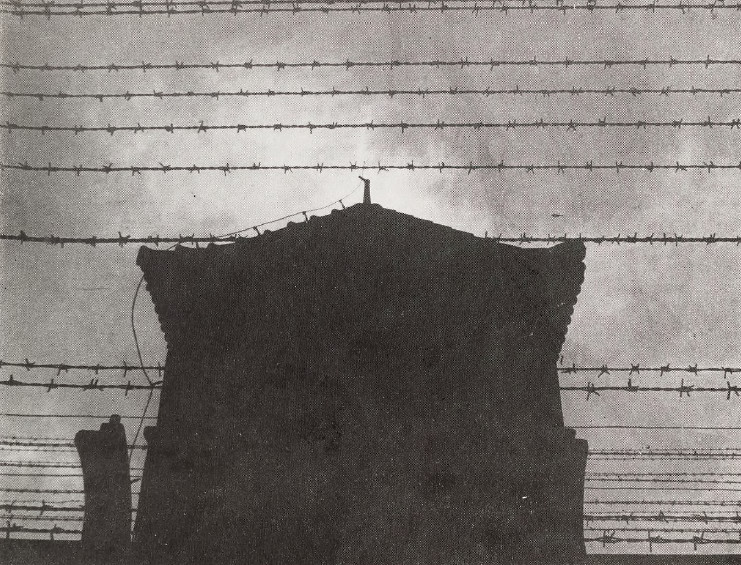

The electric fence and a guard tower at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Photograph by C.O. Mostowski

The slightest association, a remark about the Occupation made during a conversation, in films or books, forced many recollections. Associations were made especially easily when German was heard. Others could not understand this and thus the subjects developed a sense of resentment, and felt that their past experiences were not understood or appreciated. That resulted in a feeling of bitterness towards their environment, and especially towards those who were responsible for their misery. They were not able to forget. Such states appeared inconsistent with the progress of defective memory, which became poorer and poorer whereas camp recollections were increasingly vivid. Physical strength was also weaker over the course of time and this increased the sense of helplessness and weakness, and resulted in symptoms of depression. All such symptoms were of a progressive character and became more intense with time. Therefore, subjects consigned to this group were unable to perform any systematic work.

Targowla Syndrome did not appear in its classical form but in a changed version. It might be said that a permanent readiness to remember could be observed, recollections that could always be very easily evoked.

The members of all three groups, regardless of their pathological symptoms, suffered from different somatic illnesses. The variety of somatic illnesses in the former prisoners is emphasised in many works. The symptoms of somatic illnesses obviously make the moods of depression more intense. Case histories of such subjects pointed to the fact that from the time of liberation until the present time they had never completely managed to return to health. Regarding Targowla Syndrome, it should be emphasised with reference to all groups, that such reactions were evoked in different ways over the course of time. It appeared sensitivity to visual stimuli was weaker than to acoustic stimuli.

It was interesting that despite such a long period, subjects still suffered from anxiety reactions, especially those who were placed in group II, that is, the group of progressive asthenia. It should also be emphasised that the states of paroxysmal hypermnesia resulted in emotional reactions towards those who provoked them, towards Germans. Separate studies should be devoted to this topic since it was characteristic that the negative emotional reactions were still vivid despite the long period that had passed since the war. A whole scale of sensations could be observed, ranging from fear and a sense of having been wronged to aggression and hatred.

The whole of the examined group were classified as war invalids, since all of them were largely unable to perform permanent work, and many of them required constant medical care.

Conclusions

1. In the light of the foregoing research, it should be stated that the symptoms of hypermnesia can be observed in all former prisoners and that they are more intense when accompanied by states of exhaustion.

2. Hypermnesia has the form described by Targowla only in persons with the symptoms of progressive asthenia.

3. Hypermnesia has a character of the constant recollection of traumatic experiences in subjects with chronic depression. Permanent readiness to recollect the tragic past is much more frequently observed in such cases than a paroxysmal character.

4. Subjects with psycho-organic syndrome exhibit hypermnesia symptoms despite the fact that they also suffer from defective memory.

5. The character of hypermnestic paroxysms has changed over the course of time. Optical stimuli are less important as the source of paroxysms, whereas acoustic stimuli, and especially the German language, bring immediate associations with the traumatic past.

6. Defensive mechanisms in persons with progressive asthenia take the form of intensified activities; in persons with psycho-organic syndromes, they appear as a tendency to talk excessively about camp life; and persons with symptoms of chronic depression do not have any defensive mechanisms at all.

7. Progressive asthenia appears more frequently in women that in men and it is often noted in persons who were starved for long periods.

8. Organic brain injuries and the resulting psycho-organic syndrome appear more often in men than in women.

9. All symptoms commonly referred to as KZ-Syndrome have a progressive tendency and are more intense after 30 years than before, which leads to the conclusion that they should be treated as the effects of organic changes.

Translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1978.

References

1. Apfelbaum-Kowalski E. The Clinical Examination of Circulatory System Pathology in Starvation Emaciation. In: Choroba Głodowa. [English edition translated by Osnos, M. as Hunger disease: studies by the Jewish physicians in the Warsaw ghetto. New York: Wiley; 1979]. Warsaw; 1946: 190-225.2. Ărztekonferenzen der Internationalen Föderation der Widerstandskämpfer. Die chronische progressive Asthenie. Materialen der Internationale Konferenzen von Kopenhagen und Moskau, zusammengestellt vom Ärztlichen Sekretariat der Internationalen Föderation der Widerstandskämpfer. Band 1. F.I.R.

3. Baeyer W. Erlebnisbedingte Verfolgungsschäden. Der Nevrenarzt. 1961;32: 534.

4. Baeyer W., Hafner H., Kisker K.P.. Psychiatrie der Verfolgten-Psychologische und gutachtliche Erfahrungen an Opfern der national-sozialistischen Verfolgung und Vergleichbares Extrembelastungen. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1964.

5. Bieńka S.: Stan zdrowia byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych żyjących obecnie w Wielkopolsce w świetle ich obozowego doświadczenia. W 20 lat po wyzwoleniu [The state of health of former Nazi concentration camp prisoners, presently living in the Wielkopolska region in light of their camp experiences, 20 years after liberation]. Pamiętnik II krajowego zjazdu lekarzy ZBoWiD. Warsaw: PZWL; 1969: 59-71 and 85.

6. Cohen E.A. Uwagi o tzw. „KZ-syndrome” [Remarks on the so-called “KZ-Syndrome”]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1972;29: 21-23.

7. Desoille H. Comment Preserver la Santé des Invalides de Guerre, Resistants et Deportes. Comm. La conf. F.I.R. Moskau; 1957: 2.

8. Von Matussek P., Grigat R., Haibeck H., Halbach G., Kemmler R., Mantell D., Triebel A., Vardy M., Wedel G. Die Konzentrationslagerhaft und ihre Folgen. Berlin Heidelberg: New York; 1971.

9. Dominik M. Sytuacja zdrowotna i bytowa byłych więźniów oświęcimskich w świetle ankiety [Health and living conditions of former Auschwitz prisoners in light of a questionnaire]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1967;24: 102-104.

10. Eitinger L. Pathology of the Concentration Camp Syndrome. Arch. General Psychiatry. 1961;4: 371-379.

11. Eitinger L. Concentration Camp Survivors in the Post-War World. Am. Journ. Orthopsychiatry, 1963, 4, 334.

12. Fejkiel W. Choroba głodowa w obozie koncentracyjnym na podstawie własnych pięcioletnich obserwacji [Starvation disease in the concentration camp on the basis of my own five-year observations]. In: Pamiętnik XIV Zjazdu Towarzystwa Internistów Polskich we Wrocławiu w roku 1947. Wrocław; 1948: 369-373.

13. Fliederbaum J. Observations on the Starvation Diseased. In: Choroba Głodowa [English edition translated by Osnos, M. as Hunger disease: studies by the Jewish physicians in the Warsaw ghetto. New York: Wiley; 1979]. Warsaw; 1946: 81-171.

14. Hoffmeyer H. La Deportation dans les Camps de la Concentration Allemands et ses Sequelles. Ed. Croix-Rouge. Danoise; 1954.

15. Kępiński A. Tzw. „KZ-syndom”. Próba syntezy. [KZ-Syndrome: an Attempt at a synthesis]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1970;27: 18-23.

16. Kłodziński S. Swoisty stan chorobowy po przebyciu obozów hitlerowskich [A specific clinical state after imprisonment in the Nazi camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1982;39: 15-21.

17. Kowalczykowa J. Choroba głodowa w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu [Starvation disease in the Auschwitz Concentration Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1961;18: 58-67.

18. Leśniak R., Orwid M., and Szymusik A. Problemy psychiatryczne byłych więźniów Oświęcimia w świetle badań własnych [Post-camp psychiatric problems of former Auschwitz prisoners in light of personal investigations]. In: Pamiętnik XXVII zjazdu naukowego psychiatrów polskich. Krakow; 1963.

19. Leśniak R. Zmiany osobowości u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Doniesienie wstępne [Personality changes in former prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp (preliminary remarks)]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 29-30.

20. Michel M. Gesundheitsschäden durch Verfolgung und Gefangenschaft und ihre Spätfolgen. Berlin; 1955.

21. Michel M. Die Tiefe des psychologischen Traums bei Totalverfolgung. Comm. Laconf. F.I.R. Moskau; 1957: 2.

22. Münch H. Głód i czas przeżycia w obozie oświęcimskim [Starvation and the survival period in the Auschwitz Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1967;24: 79-88.

23. Nieludzka medycyna [Inhumane medicine]. Warsaw; PZWL: 1969. Commentary by Mitscherlich A., and Mielke F. (documents from the Nuremberg Trials).

24. Paul H., Herberg H.J. Psychiatrische Spätschäden nach politischer Verfolgung. Basel: S. Karger; 1963.

25. Półtawska W. Stany hipermnezji napadowej. Na marginesie badań tzw. „dzieci oświęcimskich” [States of paroxysmal hypermnesia. Supplementary remarks on the investigation into the so-called “Auschwitz children]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1967;24: 89.

26. Półtawska W., Jakubik A., Gątarski J., Sarnecki J. Wyniki badań psychiatrycznych osób urodzonych lub więzionych w dzieciństwie w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych [Results of psychiatric examinations of persons born or imprisoned in their childhood in Nazi concentration camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1966;23: 21-36.

27. Von Ritter W., von Baeyer W., Häfner H., Kisker K.P. Psychiatrie der Verfolgten. Berlin, Göttingen, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1964.

28. Richel C., Dreufus G., Fichez L. Les Sequelles des Etats de Misere Physiologique. Bull. Acad. Med.. 1948;37: 645.

29. Richel C. Pathologie de la Misere. S.D.M.S., Paris, 1957.

30. Strauss H. Besonderheiten der Nichtpsychotischen Störungen bei Opfern der Nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung und ihre Bedeutung bei der Begutachtung. Der Nervenarzt. 1957;28: 8, 344-350.

31. Szymusik A. Astenia poobozowa u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu [Progressive asthenia in former prisoners of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 23-39.

32. Targowla R. Les Sequelles Pathologiques de la deportation dans les camps de Concentration Allemands pendant la Deuxieme Guerre Mondiale’. Presse Med.; 1962: 29.

33. Targowla R. Syndrom der Asthenie der Deportierten. In: Michel, M., Gesundheitsscheden durch Verfolgung und Gefangenschaft und ihre Spätfolgen. Berlin; 1955: 30.

34. Waitz R. Zmiany chorobowe u byłych więźniarek obozów koncentracyjnych [Clinical changes in former concentration camp women-prisoners]. Translated from, ‘La Semaine des Hôpitaux’, 1941, 37, 1977-1984; La pathologie des déportés. Przegląd Lekarski. 1963;20: 41-50.