Authors

Elżbieta Leśniak, PhD, born 1939, psychologist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy, Centre for Crisis Intervention.

Roman Leśniak, MD, PhD, 1928–2003, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy. Member of the resistance movement during the Nazi German occupation of Poland.

Introduction

Polish psychiatric-psychological bibliography dealing with the aftereffects of concentration camps in former prisoners of the concentration camps is rather extensive. The problem of escapes from the camps, however, is usually discussed only in memoirs and works of fiction, for instance, in Dymy nad Birkenau (Smoke over Birkenau) by Szmaglewska, 1971, and in Anus mundi by Kielar, 1972. Rarely do scientific studies deal with the topic; it has only really been taken up in Ucieczki oświęcimskie (Escapes from Auschwitz) by Sobański, 1966, and in “Ucieczki więźniów z obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim” (“Escapes of prisonersfrom the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau,” Zeszyty Oświęcimskie, vol. 7) by Iwaszko, 1963, or in Auschwitz 1940-1945. Central Issues in the History of the Camp (vol IV) by Świebocki, 2000. The works in which escapes from the concentration camp are mentioned usually describe the ways in which escapes were prepared and performed, personal experiences of the fugitives and those who helped them, their emotional experiences and also the fate of their families who were very often victimised on account of the so‑called group responsibility introduced by the Nazis.

There are very few works dealing with the psychiatric-psychological aspects of such escapes. We have not encountered any broad study of this problem. In fact, we could only find incidental remarks. For instance, the work by Z. Ryn and S. Kłodziński (1976) on suicide among the prisoners includes the statement that the majority of suicidal acts resulted from unsuccessful attempts to escape from the camp.

The consciousness of those who dared to attempt escapes from places as strictly isolated as Nazi camps, prisons, and transports may constitute an interesting study not only for a writer of memoirs, sociologist, or concentration camp historian, but also for a psychiatrist and a psychologist. The psychiatric-psychological analysis of the prisoners who escaped from the camps, survived until the liberation, and thus were able to become the subjects of direct analyses made many years later, cannot ignore the existing multidirectional results of the psychiatric examinations, even though such examinations did not directly deal with the subject of escapes.

In the Kraków centre alone, the examinations mentioned above (Leśniak et al., 1973) provided the basis for several doctoral theses and numerous scientific papers. A. Teutsch (1964), for instance, in his doctoral thesis in the fiel of psychiatry concerning the experiences of 100 former prisoners of Auschwitz arrived at the conclusion that the first reaction to imprisonment in the camp or a lack of such a reaction was not enough to condition either a better or worse frame of mind in the prisoner or the level of his adjustment to the camp conditions. Some prisoners managed to adjust “well” to camp life despite the fact that they went through the initial reaction and others adjusted “poorly” although they did not experience any initial reaction. This phenomenon is to some degree inconsistent with the reactions observed in prisoners by Bettelheim (1953, 1962), Cohen (cf. Teutsch, 1964) and Frankl (1962). According to A. Teutsch, the inconsistency is probably connected with the fact that the majority of the examined subjects spent a long time in prison even before they were incarcerated in the camp. Moreover, the decrease in sensitivity was different in relation to different traumatic stimuli and the states of decreased sensitivity did not protect the prisoners from apathetic-depressive reactions of a breakdown type.

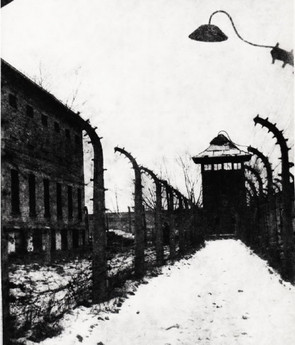

The electric fence and a guard tower at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Photograph by T. Dołżkiewicz

The camp conditions emphasised the psychosomatic unity of the human organism; regardless of the character of a traumatic stimulus, the organism reacted as a whole: physically and psychologically. Correlation between the reason of imprisonment and the adjustment to the camp was statistically proved; those who were arrested for political reasons managed to adjust better. The indirect significance of this fact is that some individual characterological features such as willpower, activity, ability to make decisions, ideological commitment, etc., proved to be essential, and helped to overcome difficult camp situations. The personality of “an ideal conspirator” might have been helpful in adjusting and surviving the camp as well (Szymusik, 1964).

M. Orwid (1964) described a number of adjustment processes in the post-camp life of the same group of camp survivors. A. Szymusik (1964) made an analysis of psychosomatic camp stress and the correlation between such stress and KZ‑Syndrome, or progressive asthenia. A. Kępiński (1973) emphasised the fact that already in the first period spent in the camp the situation was so different from the outside reality that everyone confronted with it must have experienced a shock. Later, a phase when all purposeful activities were paralysed could be observed alongside fear and helplessness reactions. Those who were not able to fight for their right to live, who could not overcome fear, hunger, pain and did not manage to think of something other than the surrounding reality at least from time to time, usually died as passive, automatically fighting organisms, deprived of all their power, reduced to the Muselmann state. Similar mechanisms and reactions were described by Frankl (1962) in former prisoners of the concentration camps.

Strauss (cf. Leśniak, 1965) described personality changes in the former prisoners caused by reactive factors; in many subjects such changes could not be observed immediately after leaving the camp but only after a longer or shorter period of time. Bayer (1961) stated that after a period of latency an asthenic-depressive phase came at the time when the former prisoners, burdened with camp memories, were exposed to the emptiness and strangeness of the surrounding world.

R. Leśniak (1965) in his research into post-camp personality changes in former prisoners, observed three types of personality disorders: depressive, suspicious, and explosive. From 100 subjects examined, only nine did not suffer from any personality disorders. In addition to the types of personality mentioned above, the following changes in attitudes towards other people could be observed:

- avoiding people, underestimating them, a lack of confidence or better estimation of others: 96 subjects;

- changes in the attitude towards life such as increased tolerance and religiousness, emphasis on moral values, greater appreciation of life, need to make the most of life, overestimation of material values, disappointment, pessimism, conviction that life is senseless, cynicism, and lack of fear of death: 62 subjects;

- permanent changes such as irritability, tearfulness, an inferiority complex, too much attention paid to health problems, greater bravery, self‑dependence and activity: 79 subjects.

The same author concludes that neither should somatic traumas take any priority nor should psychological stress bear an exclusive importance in the development and picture of the post-camp personality changes.

Recently the problem of the concentration camp has been discussed also in connection with the works by Prof. A. Kępiński (1974).

The following issues connected with escapes from concentration camps appear to be interesting from the psychiatric-psychological perspective, especially since the literature on the subject is so narrow:

1. What was the family background and living conditions of those who escaped from the camp and what made them different from millions of other prisoners who also sometimes dreamt of escaping from the camp from the beginning of their imprisonment and even had definite plans prepared but never managed to carry them out;

2. What personality features were characteristic of such people;

3. What was the stress they experienced during their stay in the camp before, during, and after their escapes and what experiences were connected with their acts of escapes;

4. What helped them to make the final decision, so dangerous not only for themselves but also for their families and those whom they left behind in the camp and who were victimised to a smaller or greater degree in different phases of the war;

5. What was their present psychosomatic state, social status, and personality characteristics;

6. What was their present estimation of the motives of their escapes that often must have caused some moral conflicts connected with devolving responsibility on others?

Research method and groups of subjects

Twenty-one escapes from the concentration camp were examined. It should be added that escapes from the camp were understood not only as escapes made from the centre of the camp but also as escapes from work commandos that extended outside the camp, from different branches of the camp, during transports from one camp to another, and during transports or evacuation marches.

The subjects were usually directed to our department through the Kraków Auschwitz Society by Stanisław Kłodziński, MD, or Teresa Reguła, MA, who were former prisoners themselves and thus well-oriented in the problems tackled by this article. According to their estimation, there are still several hundred camp escapees in Poland and around 30 of them live in the Kraków area.

The basic method was a psychiatric examination comprising such data as childhood, personalities of parents as presented by the subjects themselves, relationships within the family and the family atmosphere, school years, interests, illnesses, traumas, possible cases of poisoning, atmosphere at work, basic personality structure and its possible changes, experiences during the examination and in the camp, illnesses and traumatic stress in the camp, life development after liberation, and the present psychosomatic situation.

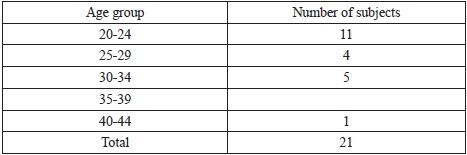

The psychological examination comprised an interview, observation, and a test method, that is, Eysenck’s Personality Inventory (EPI). The following facts were ascertained in the group described: male subjects constituted the majority of the group (19 persons) in comparison with female subjects (2 persons). At the time of their imprisonment, the subjects were from 20 to 44 years old. Age distribution is presented in Table I. As can be seen from the table, subjects who managed to perform escapes were young at the time of the imprisonment: they were from 20 to 24 years old. Out of the total number of 21 subjects, only one person was 42.

Table I: Age and number of subjects

At the time of their imprisonment, ten persons had secondary education and some of them completed their higher education after the war. Both women had secondary education at that time, two persons had higher education and nine persons elementary one.

The occupations in this group were various: there were ten manual workers, eight white‑collar workers, two persons were army soldiers, and one did not work professionally.

Single persons (17 subjects) were much more numerous than married ones (4 subjects).

At the time of the examination, the professional situation of the subjects was as follows: only five of them were pensioners. This had started only shortly before, and earlier all of them had been active and professionally effective, and only sudden outburst of numerous symptoms of disorders had prevented them from further professional work. Ten subjects worked professionally, were successful and appreciated in their environment. Six subjects not only had very important posts but also carried out charitable work.

Thus, apart from the five persons who became pensioners, the remaining subjects were professionally active and although they suffered from various and sometimes very painful and distressing ailments, they often fulfilled their duties better than their co-workers who had not had such life experiences.

Medical examinations resulted in the ascertainment of numerous ailments and disorders, and in the case of seven subjects, the disorders were very intense.

Personality

The analysis of the subjects’ pre-camp life, their interests, activities, and attitudes towards people and the surrounding world very clearly pointed to the fact that all the subjects, both in their own opinion and in the estimation of those who examined them, were extroverts.

When they described themselves, they usually used such adjectives as active, cheerful, sociable, popular, appreciating life, strong, fit, with many various interests, and sincere towards other people. A detailed analysis of their camp experiences allowed the statement that in addition to the characteristics mentioned above, the subjects could also be described as resistant to stressful situations, self-controlled and cool-headed when confronted with problems and difficulties, determined in their actions, competent and accurate, resourceful, and able to control their own movements no matter how quick or sudden they were.

An examination made with the Eysenck’s Personality Inventory method resulted in establishing the following information about the subjects’ post‑camp personalities: extroversion was ascertained in all cases in the pre‑camp period, in the post‑camp period intensified extroversion could be observed in four persons, extroversion in eight persons, introversion in eight persons, and intensified introversion in four persons.

Personality changes in the subjects with intensified extroversion comprised tension, impatience, violent reactions, and creating conflicts within their environment without which the subjects could not imagine their lives. Personality changes in subjects with introversion and intensified introversion could be described as frequent cases of total seclusion from their environment, depression, lack of interest, exhaustion caused by psychological experiences and anxiety. In 16 subjects, personality disorders resulted in either intensified extrovert features (four subjects) or changes in the system of personality features from extroversion to introversion (12 subjects).

Regarding the parents of the examined subjects, mothers were usually very active, dominating the rest of the family, resourceful, very closely connected with the family, and at the same time sincere and protective. Consequently, the subjects could always be sure of their moral support. Such mothers were often demanding and consistent in their educational methods. Fathers were usually also sincere, paying attention to their homes and families, but with a different attitude towards life. The subjects usually complained that their fathers were too engaged in their professional work and sometimes abused alcohol.

In general, there was usually very close emotional contact in such families, everybody was ready to help one another, and the atmosphere was patriotic and religious. Such families not only provided strong emotional support but also demanded a lot. This, however, was done in such a way that no difficulties in pursuing individual interests and talents were raised, and sports and activities in different organisations were especially encouraged.

It was characteristic that almost all the subjects practised at least one or more sports, which enabled them to be fit all the time. Most of them became hardened by the lives they led, and later by self-education, earlier difficulties, and problems (for example, orphanhood, or financial problems in the family).

Almost all of the subjects emphasised their active attitude towards life, bravery, and the ability to properly estimate their capacities. Moreover, all of them had many talents, could be described as people of decision and resourcefulness, and they were all consistent in their actions. For many male subjects the period of their military service as well as fighting in 1939 and their underground activities provided the chance to prove their abilities.

In a situation of extreme psychological and biological stress, distressing humiliation, injustice, physical torture, and all the evil brought by the concentration camps, the majority of the subjects did not lose their faith in survival and thought of escaping. They prepared plans, were determined and consistent, and able to overcome their anxiety and fear of death in the camp conditions. Confronted with situations of imminent danger and obstacles that appeared impossible to eliminate, they were able to concentrate and plan carefully, and control their reactions and desires even if their situation appeared to be hopeless. Some of them were stimulated by danger, which forced them to concentrate to the maximum and be ready to perform any reasonable action.

Except for two persons, all the subjects started to plan their escapes immediately after their imprisonment and analysed every possibility that might be taken into consideration in camp conditions. As a rule, their greatest concern was the thirst for freedom they dreamt about day and night. Some of them had the chance to escape earlier but did not because they worried about their families and fellow prisoners who might be victimised later.

The desire to save their lives and regain freedom was the most frequent motive for escape (seven subjects). However, there were also prisoners who were aware of the fact that they would very soon die of some illness or because they would approach the Muselmann state if they did not escape. In those cases their psychological state was so bad that they were not able to understand simple logical facts such as that they did not have any real plans for escaping, that they did not organise any help from the outside that might be offered to them after the escape, or that their families and colleagues would have to bear the responsibility (six subjects). Six subjects knew that they were important witnesses for the Gestapo and that they would have to die after the interrogations. Two subjects explained that their motives were to do something great, exceptional, and commonly regarded as impossible to perform. These people maintained that they wanted to inform the world about the real situation in the concentration camp.

More than a half of the subjects made several escape attempts but those ended in failure. Some of these escapees went back to the camps where they were punished “appropriately” but not killed; others were imprisoned in different camps under different names, because they managed to convince the Nazis that they were different people.

The following example illustrates the personality and traumatic experiences of one of the fugitives. It might be worthwhile to quote all the details presented by the subject since the events he describes, although real, might make one think that they could not have happened.

Prisoner K. Ch. was 54 at the time of the examination. His father, a Polish State Railways supervisor, was sincere, open, and sociable. Sometimes it was impossible to argue with him. His mother was placable, hardworking, understanding, and cheerful. The parents got on well. The subject, the youngest of the four children, had a brother and two sisters. Although he was much younger than the rest of the family, they all lived in unity and the atmosphere at home was “sunny and religious.”

The subject developed normally, finished elementary school, and then completed his secondary classical education. Although he received low marks and even had to repeat the sixth grade, as he neglected his duties at school, he was popular with his schoolmates. After he finished secondary school, he became a student in a military college. Then the war broke out. He took part in the 1939 Defensive War and then returned home. At first, he did not work but in 1940, he undertook the job of a manual worker in a quarry. Later he changed his place of work several times. In the meantime, he became a member of the ZWZ (Polish Związek Walki Zbrojnej, Union of Armed Struggle) and was a platoon officer. Having been arrested in 1942, he was interrogated and tortured every day since the Germans expected him to give away the pseudonyms and names of other members of the organisation. The tortures included whipping and the use of the infamous “pole with handcuffs,” by means of which he was raised and hung, and when he fainted, the perpetrator would free him from the handcuffs and bring him round to kick him. After such examinations carried out by the notorious torturer Haman, he admitted he was guilty but he gave nobody away.

On 21 January 1942, he was transported from the prison in Tarnów to Auschwitz. It was very difficult for him to adjust to the camp conditions because he knew that nobody was supposed to leave the camp alive. In his first period there, he suffered a difficult case of tonsillitis with a high temperature and then he was offered help and sympathy from his fellow prisoners who instructed him how to avoid dangers in everyday camp life. One of the prisoners taught him a very important and basic principle, “Remember you have to survive until the end of the day.” And he did. Due to the help of his colleagues and the knowledge he got from them, he was moved to a commando where he could work with a roof above his head and without such strict control.

In August, he was moved to Neuengamme with a large transport of prisoners and then to the camp in Bremen where he worked in a formed tractor factory until the time of several air raids. The work there was very strenuous because he had to pull out 11 kg cartridge‑cases, 17 sets a day. Heavy work and very small food rations almost brought him to the Muselmann state; he realised that he would have to die. He was saved by an air raid after which the prisoners had to live in barracks without roofs, exposed to snow and rain with smaller and smaller food rations. He planned an escape in Bremen but did not want to escape on his own. His friends thought his plan was hopeless because they would all have to travel for a long time through areas inhabited by Germans. Later, he made another decision to escape with 10 other prisoners. Somehow, the Germans learnt of his plan, and two Russians from their group were taken and interrogated. They did not betray the rest of the group.

When he finally realised he would never be able to survive, he decided to escape on his own although he was full of doubts and anxiety. He made clothes for himself from an old blanket but they fell apart and he could not use them. In the meantime, his plan was ready. During the previous air raid, the fence surrounding the camp had been damaged and it was enough to wait for the next air raid. It came at a convenient moment when he and other prisoners were trying to lift a log. In the confusion in the camp, he managed to hide in the ruins of a bunker under a pile of bricks until the evening. The night was very bright and he had to pass a number of “stands”. He decided to take a very risky route across a potato field near the guards and he was in the middle of the field when he noticed a commandant. He thought it was the end and waited in the field, but he was not noticed.

He reached a railway station which had also been bombed. When a train arrived, he got into a brake van but there was a German conductor on the other side of it who made him leave. He spent many hours waiting and when the train was leaving he got on it again. Unfortunately, the train made only a short journey and went back to Bremen. Next, he got on a freight train. He had no food and was still wearing his striped camp clothing. After three days of travelling by freight train he arrived at Halle and there changed for a train to Wrocław. In Wrocław he saw a Bahnschutz [German “railway guard”] and later a gendarme which scared him so much that he spent the whole night among the pipes of the running gear. In the morning, he set out on foot to Chrzanów because his brother lived in the area. His legs were bleeding, he was exhausted and hungry.

That night found him in a forest. He was so tired that he kept falling over all the time. He knew he would freeze if he stayed in the forest but also knew that people were dangerous for him. At one moment, he saw he was surrounded by many lights. When he approached them, however, they disappeared. After several experiences like that he was convinced he was seeing things. He walked farther on and finally saw a factory and two people in front of it who advised him to disappear from that area. But he had already seen a room with a warm stove and people, and was not able to walk away although he was aware of the danger. He invented some story and stayed with the workers. When, after a quarter of an hour, gendarmes rushed into the room and aimed their guns at him, he was indifferent. He was even glad that everything would end. However, one of the soldiers realised that he must have been an Auschwitz fugitive and the next day, after a night spent in the cellar with rats he was no longer able to defend against, he was transported to Auschwitz.

There he met Boger, a German, who swore, “You’ll be hanged.” He accepted the statement without any emotions. He was put in Block 11 and examined in the political section of the camp the next day. They asked who helped him to escape. He stayed in Block 11 until 18 January 1945, the time of the evacuation. During the evacuation, despite all his past experiences, he escaped from the column of Block 11; he went to a doctor who helped him to find a hiding place and changed his camp number. By 20 January 1945, there were no guards in the camp and he decided to leave his hiding place and look for some food. Unfortunately, he was caught by a Gestapo soldier who selected ill prisoners to be shot in the camp. Somehow, he managed to escape from that group again, hid himself in Block 16, and waited there until liberation. The day of liberation has since been the one he considers the happiest one in his life.

The subject was always an optimist: cheerful, active, sociable, popular, and open to contact with others. The escapes described above point to other characteristics in his personality as well. His consistency should certainly be emphasised as well as his uncompromising attitude in the fight for life, his resistance, and bravery. The experiences he managed to live through might also be an illustration of the psychological capbilities of a human being who had to overcome the most serious, dangerous, and difficult situations in a strange and hostile world without the possibility to communicate in a foreign language, without the proper clothes, food, or money.

It should be emphasised that the escapes were usually performed in groups, sometimes quite numerous (several people). Group escapes were made in 12 cases among the examined subjects; the rest had escaped on their own. Many of those who participated in escapes were quickly killed. Those remaining continued their escapes individually, scattered all over the area. Often they were unable to act according to their earlier plans, or follow the routes or contact the people they had intended to. In group escapes, those who could communicate in German, knew the country and the people, were the most important.

For psychological reasons group escapes were better than solitary ones. The group offered support, help, and community spirit, although there were also cases of various conflicts among the members of the group resulting from contradictory aims or conflicts between individuals.

Everyone who planned an escape was in permanent danger; one of the subjects said, “In the camp one was punished even for thinking of an escape”; all of them had to suffer the sight of prisoners and also their families who were tortured and murdered as a punishment for someone’s escape. The situation described by subject W.C. may serve as an example of the stress the prisoners preparing escapes were confronted with.

He was 56 at the time of the examination. He described his father as a wise and tactful man, always ready to help and give advice, and fond of homelife. His mother was explosive, intolerant, and always to the point. The parents lived harmoniously; despite the difference in their characters the atmosphere at home was peaceful. The subject was a good pupil. He was often described as “a restless creature.” He was cheerful, happy, open, active, and politically committed. In 1939, he became a member of ZWZ, and in 1941, he was arrested because of an informer in the organisation. He did not admit anything during the interrogations, and in May 1941, he was moved to Auschwitz where he was examined three times more and severely beaten. On one occasion, he lost consciousness. He experienced a short loss of consciousness three more times under psychological stress. His first year in the camp was very difficult; he could not adjust to the living conditions. By November 1942, he was completely deaf and had swollen fingers that looked like sausages. Then, with the help of his fellow prisoners, he was moved to a so-called geodesist commando.

Barracks at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp

He had dreamt of an escape since the beginning of his imprisonment. However, it was only when he had the chance to go out with other prisoners to make measurements and sometimes met people outside the camp that his escape plans became more realistic. Due to the type of work he performed, he knew every little piece of land around the camp. The escape was planned with “mathematical precision”; he did not escape initially because he was aware that his family and fellow prisoners would be severally punished afterwards. He planned his escape for several months, extremely sensitive to everything that took place around him in the camp. He planned to escape with some other prisoners and he brought his plan into practice only after he learnt that the Russian army had overtaken the area where his family lived.

All the fugitives had civilian clothes and were waiting in a barrack outside the camp until the evening. At night, they decided to cross the outer Postenkette [German “sentry cordon”]. They were deeply convinced that they would be successful and despite various difficulties and many hours of constant danger, due to their self-control and the fact that they were familiar with the area, they managed to reach a safe place outside the camp and, later, their homes.

It was a very risky but precisely planned escape. Although it was successful, even at the time of the examination the subject was haunted by nightmares about difficulties and failures connected with fleeing from the camp. Such dreams bring back the threatening atmospere and uncontrollable anxiety. He is afraid even to talk about those experiences since he knows his anxiety would automatically grow stronger.

The most traumatic moment that the subject will never forget took place several months before his escape and is presented below.

As a punishment for an escape organised by another group of prisoners, his commando was decimated. Prisoners were taken to be shot both at roll calls and during work time. He and his friend were the only ones who survived from among the older prisoners. One day he looked through the window of his block and saw a prisoner overseer, a kapo, who usually selected prisoners to be killed and who was approaching the block. Terrified, he watched the kapo’s movements. Then, they all heard him coming into the block and going in their direction; when the door handle moved they understood he was coming into their room.

When the subject saw the kapo he felt as if he had been already dead and those had been the last moments of his life. He reported to the kapo and could not understand that the German was asking for some details connected with the work they had performed recently. When the kapo left, he felt so weak that he fell on a chair and for a long time he could not get rid of a painful tension and general psychological discomfort. Also, he could not believe he was still alive. In comparison to the long-lasting psychological tension experienced while preparing to flee, the subject was very calm and fearless during the escape itself. He was very consistent in his actions, ready to undertake any risk that would offer a chance to save his life.

Among the group escapes, there were also cases of mixed group attempts. We can quote a record of an escape performed by a prisoner, a kapo, and an SS-man, described by prisoner E.P. who was 63 at the time of the examination. They went on foot from Auschwitz to Krzeszowice where they were caught. An accidentally encountered farmer provided them with the food they asked for and they paid for in marks. The same farmer, however, informed on them to the police immediately afterwards.

The subject who presented this story believed that they were able to survive their return to Auschwitz only because his father, a kapo, had the opportunity to plead with the authorities for his son and knew how to defend him. When they were brought back to the camp the first order they heard was that they would be killed with sticks. They were beaten, kicked, and forced to crawl for three days and nights and were constantly afraid that they would die. After the subject was released from the underground cell in which he was kept, the most difficult and exhausting work was assigned to him.

Solitary escapes often contained elements of psychological danger that were not foreseen by the escapees. The result was that when liberation came they felt isolated and lonely instead of feeling happy. Solitary escapes that were organised by prisoners who were in a danger of immediate death either because they were Muselmänner or worked over‑excessively were particularly desperate. Such escapes were frequently the last possible effort the prisoners could make, and were usually performed in quite accidental circumstances, without any basic food supplies. Extreme psychological tension, the inability to communicate in a foreign language and a complete lack of knowledge of the country usually contributed to the failures of the escapes. Psychological reactions to hunger, cold, and isolation made the prisoners ignorant of their environment and they desperately tried to escape or to finish their life and misery. We noticed many indications of such a state when we analysed the story told by prisoner K.Ch.

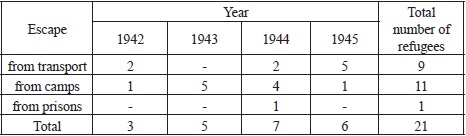

It would be impossible to compare the escapes from the perspective of the time and the circumstances in which they were organised. An attempt to classify the escapes, however, should be made. The subjectss examined at our department attempted to escape from the camp, a transport, or a prison, and the attempts took place between 1942 and the end of the war.

Table II includes data concerning the years and places from which the examined finally escaped. An analysis of the data concerning the circumstances of the escapes pointed to the fact that 12 subjects tried to escape only once and, for 10 of these, this was the first and successful escape. In four cases, the escapes were made from the camp, in five cases from transports, and in one case from a prison. Two subjects attempted an escape but their plans failed and after the punishment they received, they never tried again.

Table II: Time and place of the final escape

The remaining nine subjects undertook attempts to escape at least twice. Three subjects failed every time even though they sometimes managed to remain outside the camp for several months, and sometimes were arrested within a step of their second or third attempt. Their way to freedom, however, was very long.

S.M., 53 at the time of the examination, described his escape that might be an illustration of the difficulties met by the escapees. His father was a supervisor, good-tempered, sociable, sincere, open, and could talk about everything. His mother was cheerful, good‑tempered, self‑controlled and it was her that ruled the house. The parents got on very well: there was a good and warm atmosphere at home. The subject was the youngest of several children. He developed normally, was a good pupil, active at school, popular with school friends, and performed various functions in the student government organisation. By the time the war broke out, he had managed to complete his secondary education and passed the final examinations. He was sociable, cheerful, energetic, enjoyed playing cards, making long trips, never thought of himself as of “an individual.” He was arrested in September 1943 for membership in an underground organisation. He was imprisoned for two days in Krzeszowice, then in Montelupi, and finally transported to Auschwitz and in 1943 to Buchenwald. During the prison interrogations, he was tortured and beaten until he lost consciousness. The first period spent in the camp was very difficult, especially when he had to stand barefoot for many hours at roll calls. Later he was beaten by an SS-man and kapo because he was falsely suspected of queuing for food twice. All the time he suffered from cold and hunger.

He had considered the possibility of escaping from the camp since almost his first moment there; he was constantly afraid that he would not manage to survive. He made his first attempt in April 1944, after an air raid. He escaped together with a group of other prisoners. They only managed to make several kilometres before they were caught by the Selbstschutz [German “paramilitary defence unit”]. He pushed a German and tried to escape but unsuccessfully. All the fugitives were severally beaten and lost consciousness before they were brought back to the camp where they were questioned and beaten again. On their way back to the camp, they could see other escapees killed during their attempts to escape.

After the period of questioning and interrogation, he went back to his everyday work. He worked with bricklayers who would leave the camp everyday to build a cottage in the forest. In October 1944, he tried to escape again; he did not even hope that he would reach his homeland, but rather that he might have been able to get to the German‑American frontline, which was 70 kilometres from the camp. He escaped with a Forarbeiter [German “overseer”] since he knew German. He had a “civilian” sweater but his trousers and jacket were striped prison clothes. During the escape, his companion left him unexpectedly.

At the beginning he was so weak that he could not walk, later he felt slightly better and got a jacket that he found on a scarecrow. He did not have anything to eat; he met a Pole working in the field that introduced him to a Bauer [German “farm owner”] as his cousin and asked for a job for him. The Bauer’s wife, however, called the police and showed them the new worker. The subject thought the message about his escape had come from the camp. He was arrested and taken to Solingen where he said he was a farm worker who had escaped from Aachen after an air raid. A Gestapo man who questioned him decided that he should be taken to a concentration camp; the fugitive “prayed to God that it would not be the camp he escaped from.” Finally, however, he was taken to a labour camp. He had a Ukrainian baptismal certificate for the name “Nestor Ślusarczyk” and on this basis he was given a work certificate and sent to work in Hanover.

He went there but on his way to the camp, he met some Polish people who gave him bread and money with which he bought a ticket to Bytom. When he was approaching his train an SS-man stopped him. He was terrified and thought he would be caught again but the SS-man only asked for matches. His documents were checked several times but he managed to arrive in Katowice. He stayed with his brother for a short time, but was ill, weak, and unable to undertake any work. His weighed 45 kg. He had nightmares about his escape every night: he was hiding somewhere and then was caught to be killed. He still suffered from such nightmares at the time of the examination at the Department of Psychiatry. He maintained that he had escaped because he was scared, “it seemed to me that I had a greater chance to survive if I escaped, it was not bravery, it was done out of fear, the punishment was a sentence to be shot.”

The subjects experienced different feelings connected with the fact that they regained freedom; sometimes they felt so passionate, surprised, and paralysed that they were unable to do anything.

An example of such an experience was provided by subject K.W., 74 at the time of the examination. His father was an engine driver, good‑tempered, sociable, sincere, and open. His mother made all the decisions in the family; she was cheerful, hospitable, and energetic. He was the middle child in the family and had a very good childhood. The atmosphere at home was warm. He was a good pupil, completed technical school of mechanics, and at work was promoted from a printer to a supervisor. He married when he was 21. From the beginning of the Occupation, he took part in the underground movement. After a “give-away” his wife and elder son were arrested. When he learnt about their death in the camp, he fainted. He quickly adjusted to camp conditions; his knowledge of German helped him a lot. Constant humiliation, a sense of helplessness, and the necessity to “bow” to SS-men, however, were most difficult to accept. He managed to live through all the difficult moments because of his great hope; he was popular with young prisoners since he was full of energy and humour.

As he worked in a camp printing house, he was able to prepare documents for himself and to make contact with civilians working in the camp. With their help, in turn, he made contact with nuns and was provided with some food and clothes.

The plan of his escape was very simple: he was to go outside the camp with other workers, wearing his civilian clothes, and then to be helped by the prioress of the local monastery. He put his plan into practice at the first convenient moment. When he found himself outside the camp gate, however, he was struck with a sudden thought, “It was so easy to get out of here and still I lived in that nightmare for so long,” he stood rooted to the spot, “I was sweating bullets, unable to move, I saw a German at the gate who knew me and could recognise me easily, but I could not move.” It was only when one of the workers touched his shoulder and said “You gotta go or it won’t be nice at all,” that he made a great effort and walked on. But he could not get rid of the feeling that he would be arrested any moment.

When he finally dragged himself to the nunnery where he was to be instructed where to look for further help, he was sweating, his hands were shaking, and he was sure that his appearance must have looked suspicious to the doorkeeper. He could feel the sweat all over his face and in his shoes, and all his clothes were wet. Despite the fact that he was in a safe place, he was afraid and could not stop sweating for a long time. He had anxiety nightmares about his escape, he dreamt that he was tortured, standing during roll call and waiting for punishment.

Before the end of the war, when he gradually became used to his new situation and more and more often would leave the house in which he lived, he had to live through one more dangerous moment. At the market square in Kęty, he met his direct superior from the camp and was recognised. Paralysed with fear he obediently followed him to a restaurant for Germans where his prosecutor bought him a beer. The subject could not stomach it and could not believe in any good intentions on the part of the German. All the time he watched the German’s movements carefully and wondered what would happen to him. He did not want to be killed in the last days of the war, after all he had experienced: he thought intensely about what he should do. When the German let him free after they left the restaurant, he walked like a lunatic, awaiting a shot at every moment; he got to the corner with great difficulty and then started to run convinced that he had to escape from the danger that was still awaiting him.

It was clear from the subject’s life history that he was always resourceful, energetic, and emotionally connected with other people. He was always ready to offer help, liked to have others around, appreciated life and was always patriotic. He had never experienced fear and anxiety until he found himself in the camp. When he was questioned and tortured in the camp, he was happy if he was able to overcome pain and misery.

A psychiatric-psychological estimation of the escapee supports the statement that he managed to adjust quickly to the camp conditions mainly because of his knowledge of German; it enabled him to undertake work in the camp printing house, which prevented him from the psychosomatic loss of his strength. The deaths in his family, anxiety, and the desire to be free were the motives of his escape. Despite the most favourable conditions, he experienced a short reactive episode during the escape, when he was not able to walk any farther, and he would probably have never managed to escape if it were not for his colleagues. He lived through a similar episode again after he regained freedom: when he was in Kęty and met the SS-man who knew and recognised him.

It might be worthwhile to take a clear look at the subject of escapes from transports, although the conditions in which such escapes were made were very different from the specific situation of the escapes from the camp.

An illustration of an escape made from a transport and its permanent aftereffects in the personality of the former prisoner can be seen in the example of J.K. She was 31 at the time she was arrested with her mother for political reasons in January 1942. She had developed normally. Both parents were extroverts, and her father was very strict with his only daughter.

Before imprisonment the subject was cheerful, open, sociable, talented, but a bit lazy. She swam and played volleyball; she was energetic, resourceful and trusted other people. She started to work professionally after she completed her secondary education.

After she was arrested, she was often beaten during interrogations. In the Montelupi prison, two of her teeth were knocked out. Her most difficult moments in the camp came when she was beaten by female German guards, when she had to live without water and in squalor that she could never manage to become used to. In Auschwitz, she soon suffered from Durchfall [German “diarrhoea”] and typhus fever with normal progression but serious aftereffects: since that time, she had often had flu, tonsillitis, and colds. In the camp she worked in an SS‑laundry; she was then selected for a small “sick room” and was vaccinated intramuscularly with bacteria. After the vaccination she came out in a rash, her skin was covered with eczema and she had to spend three weeks in the sick room; afterwards she returned to Birkenau.

In her opinion, she was able to survive due to her very deep faith, the possibility of contacting her mother and later, when she was moved to a “better” commando at Rajsko, food supplies provided by her friends.

She decided to escape from the transport to Germany together with two fellow prisoners who were also convinced that they would die in Germany among strangers. At the beginning, they went to Wodzisław on foot. The road was full of dead bodies. When the route column was formed at 6 o’clock in Jastrząb and it turned out that twenty prisoners were missing, the fugitives were immediately discovered in a barn and beaten with riffle butts. One of them was killed. The rest rushed out and pretended they wanted to join the column. They witnessed many other executions but finally managed to hide in dung where they spent a cold winter night.

They escaped hidden in a herd of cows so that SS-guards did not notice them. They came to a cottage where people spoke a Silesian dialect and pretended that they were on their way back from Germany. They stayed in the cottage for two months, until the time the frontline reached them. The subject returned home, stayed with a friend for three weeks, and then managed to obtain the keys to her own flat. She started professional work. At the end of 1945, her mother returned from Ravensbrück and in 1947, her father joined them.

In 1948, she married a former prisoner whom she had met in the camp. She thought he was a man who would be able to understand her. They both frequently met with other camp survivors.

Her personality changed after the camp experiences: she no longer cared about “the details”; “I want to eat at least once a day,” she said, “sleep in my own bed – everything else is of secondary importance.” The memories of the camp nightmare haunted her incessantly and became stronger with the course of time; she could not sleep well for several years, had nightmares, lived through her escape repeatedly, and woke up in tears convinced that she had just been caught. Death could not impress her: “Nothing matters much; I still live in the camp.”

In 1957, she received the second-group disability benefit, because of a long chronic rheumatic fever that dated back to the camp period.

Finally, it should be added that none of the subjects talked about his or her escape as of an act of heroism; many of them felt guilty towards their fellow prisoners and that feeling was manifested both in their dreams and in various difficult memories. Many of the former prisoners, including those who managed to escape successfully, suffered from nightmares and recollections about either the details of their escapes or the punishment they were to receive for attempting escapes. They usually woke up in panic a moment before they were to be tortured or killed after they were caught in their dreams.

Conclusions

Based on the psychiatric-psychological examinations of former prisoners who managed to escape from concentration camps and the subsequent analysis of their experiences and consciousness, the following observations were made:

1. The subjects came from families with close emotional contact and a good atmosphere. Mothers were usually the central persons who consolidated the families and provided moral support. It was usually they who knew how to motivate their children to work and pursue their interests. Fathers were active and professionally skilful. The subjects usually described them as good, sincere, etc.

2. An analysis of their life developments resulted in the observation that in the majority of cases they were sociable, popular, energetic, resourceful, active, and capable of making reasonable plans for all their activities. Most of the subjects could easily cooperate with others, were persistent in overcoming difficulties they met, had deep respect for life and freedom; many of them were courageous or had an inclination to take risks.

3. The majority of the subjects were young at the time they were arrested (20 subjects were less than 34), they were strong, athletic, psychologically and physically fit.

4. Most of the subjects were arrested for political reasons because of their underground activities; they were examined and questioned before they were transported to the camp and both at that time and later they were exposed to serious psychosomatic traumas.

5. Three basic motives of the decision to escape were distinguished:

- 12 subjects stated that they attempted escapes because they were deeply convinced that they would soon die because they were either in danger of immediate extermination or close to the Muselmann state

- deep respect for life and freedom combined with a readiness to make any sacrifice in the name of those values were the motives for seven subjects who participated in various escapes made by various groups of prisoners;

- two subjects wanted to perform deeds commonly regarded as impossible and they escaped because they wanted to be able to tell the truth about the Auschwitz camp.

6. The majority of the subjects were starving during their escapes, were exposed to unfavourable weather conditions and constant fear that they might be caught (some of them were, in fact, caught).

7. From the psychiatric-psychological perspective, as was illustrated above by the detailed descriptions made by the subjects themselves, many of them suffered from strong anxiety neuroses and functional reactions up to psychoses accompanied by hallucinations.

8. In addition to the commonly known syndrome of progressive asthenia, serious states of anxiety connected with the escape that came both in nightmares and daydreams were frequent symptoms in many subjects.

Adapted and translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1976.

References

1. Baeyer W.R. Erlebnisbedingte Verfolgungsschaden. Der Nervenarzt. 1961;32: 530-538.2. Bettelheim B. Individual and Mass Behaviour in Extreme Situations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology. 1953;48: 534-538.

3. Bettelheim B. The Informed Heart: Autonomy in a Mass Age. New York: Free Press of Glencoe; 1962.

4. Frankl V.E. Psycholog w obozie koncentracyjnym [A psychologist in the concentration camp]. In: Apel Skazanych [Roll call for the condemned to death]. Warsaw: Pax; 1962.

5. Iwaszko T. Ucieczki więźniów z obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim [Escapes of prisoners from the concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau]. Zeszyty Oświęcimskie. 1963; vol. 7.

6. Kępiński A. Rytm życia [The Rhythm of Life]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie; 1973.

7. Kielar W. Anus mundi. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie; 1972.

8. Leśniak R. Poobozowe zmiany osobowości byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Translated as “Post-Camp Personality Alterations in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1965;22: 13-20.

9. Leśniak R., Orwid M., Szymusik A., Teutsch A., Gątarski J., Dominik M. Resume der Krakauer Psychiatrischen Untersuchungen Ehemaliger Konzentrationlager-haftlinge. In Ermedung und vorzeitiges Altem. Folge von Extrembelastungen. V. Internationaler Medizinischer Kongress der FIR 21. bis 24. September 1970 in Paris. Medizinischen Komission der FIR, J. A. Barth, Leipzig; 1973: 201-203.

10. Leśniak R., Orwid M., Szymusik A., Teutsch A., Gątarski J., Dominik M. Review of the Krakow Psychiatric Studies of Former Prisoners of Concentration Camps. International Congress of Social Psychiatry, Vol. 2, Zagreb; September 1970: 265-267.

11. Leśniak R., Masłowski J. Psychiatryczna problematyka obozów hitlerowskich w pracach Antoniego Kępińskiego [Psychiatric problems of the Nazi camps in the Works of Antoni Kępiński]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1974;31: 13-18.

12. Orwid M. Socjo-psychiatryczne następstwa pobytu w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim-Brzezinka [ Socio-psychological aftereffects of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964: 21, 17-23.

13. Ryn Z., Kłodziński S. Z problematyki samobójstw w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Translated as “Suicide in the Nazi Concentration Camps”. Przegląd Lekarski. 1976;33: 25-46.

14. Sobański T. Ucieczki oświęcimskie [Auschwitz escapes]. Warsaw: MON; 1966.

15. Szmaglewska S. Dymy nad Birkenau [Smoke over Birkenau]. Warsaw: Czytelnik; 1971.

16. Szymusik A. Astenia poobozowa u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu. Translated as “Progressive Asthenia in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 23-39.

17. Świebocki H. Auschwitz 1940-1945. Central Issues in the History of the Camp. Vol IV. Oświęcim; 2000.

18. Teutsch A. Reakcje psychiczne w czasie działania psychofizycznego stressu [stresu] u byłych 100 więźniów w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Translated as “Psychological Reactions to Psychosomatic Stress in 100 Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 12-17.