Authors

Małgorzata Dominik, MD, 1941–1979, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy.

Aleksander Teutsch, MD, 1918–1980, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy.Reports on psychiatric and psychological examinations of children whose parents survived Nazi oppression did not appear in the scientific literature until 1968. The studies paid particular attention to a specific negative impact that survivors’ psychophysical disorders exerted on family relations and on children born after their parents’ return from a concentration camp. Psychiatrists from many countries such as Canada, the USA and Israel found peculiar anomalies in the behaviour of these children in adolescence. From what we know thanks to developmental psychology, adolescence is a crisis point in life, very often marked by the onset of various behavioural disorders in young people, which oftentimes reflect inappropriate parental attitudes and the atmosphere prevailing within the family. Hence it is no coincidence that the first observations of survivors’ offspring involved adolescents.

Trossman (1968) presented a description of individual cases of behavioural disorders in survivors’ adolescent children. In the same year, Krystal observed the negative impact of survivors’ aggressive behaviour on their children’s personalities and the transmission of pathologies from a survivor parent to the next generation. On the basis of a few case studies of patients given psychoanalytical treatment, Blos (1968) and Kerstenberg (1974) observed that the children of survivors developed a marked tendency to identify with their parents, and that they had nightmares similar to those afflicting their parents, namely on the same subjects related to war and oppression. The children had the same nightmares, although the parents claimed they had never told them about their wartime experiences. Laufer (1970) and Brody (1971) wrote of the children’s strong sense of identification with the victimised parent. They described a number of psychopathological symptoms in their adolescent patients, such as infantile omnipotence disorders, inhibited aggression, body schema, body image disorders and phobias. All these symptoms could be directly correlated with the transfer of parents’ experiences to their children.

There was vivid interest in the specificity of disorders in survivors’ adolescent children at the 1969 International Congress of Psychoanalytic Associations in Rome, when a questionnaire was sent to 320 psychoanalysts from different countries. The aim of the questionnaire was to determine whether survivors’ children shared some specific features of character, differing them from the offspring of parents who had not been concentration camp inmates. The results of the questionnaire were summed up at the next Congress of Psychoanalytic Associations, which was held in Jerusalem. A similar questionnaire was distributed in 1969-1970 to members of the Association for Child Psychoanalysis, and in 1971 the issues raised in it were discussed at the conference organised by the American Psychoanalytic Association. Kerstenberg (1974) published the results of the discussion and the replies to the questionnaire. Respondents (mainly from the USA, the UK and Israel) provided very different answers; some expressed their doubts whether it was possible at all to relate the adolescent disorders of survivors’ children to their parents’ wartime experiences. Others said that no specific common traits could be established in survivors’ children (Rosenberg, 1970), and the only peculiarity was observed for their parents, who were overprotective and strongly committed to ensuring material security for their children. However, Blos, Laufer, and Brody did observe specific pathological behaviours in these adolescents. Some answers (e.g. Furman, 1971) took the view that the negative psychological consequences observed in the children of survivors resulted not so much from the pathological attitudes of their parents caused by their wartime experiences, but rather from the physical relocation of both parents and their offspring into a completely new cultural environment of post-war reality. Furman meant Jewish families from Eastern Europe who resettled after the War in the USA, Canada, or Israel.

This line of enquiry was continued by Kerstenberg (1974), who noted that people who had been oppressed on racial or ethnic grounds developed a sense of impairment in their new social group, as well as a sense of low self-esteem in relation to citizens of their new country. There was, therefore, a high risk that parents would transmit this disposition to their children, and view them with the same low esteem, as inferior – viz. less commendable and admirable, less talented, and less attractive than their peers. Another unfavourable attitude manifested by the parents were their excessive expectations of their children, i.e. expecting them to accomplish remarkable achievements in their lives, which could in a way compensate for their own non-achievement caused by their pathologically low self-esteem. Moreover, many survivors of Nazi German oppression constantly felt sad and had a sense of an irreversible depletion of their mental integrality, irretrievably lost during the war, which certainly had a negative influence on their family relations.

Lipkowitz (1974) made a similar observation, namely that people released from Nazi German concentration camps and prisons could not achieve a personality restitution sufficient for them to develop the right kind of emotional bond with another person, (in this case with their child), thus their post-camp mental changes – their concentration camp syndrome – passed down to the next generation (via the process of identification in early childhood). From what we know from the published psychoanalytic research, the factor which has the largest impact on the shaping of an individual’s personality is the way his parents communicate with him in his early childhood. The child assimilates the image of his parents through identification (introjection), thus making them a key part of his superego.

Sigal and his associates (1971, 1973) used these assumptions as a point of departure for a broader research project on the offspring of survivors. Sigal proposed a hypothesis that a person who went through a spell of profound deprivation in childhood or adolescence developed traits which affected both his own development and personal relations, as well as his attitude to his family, including his children. He examined 32 Jewish families from Central and Eastern Europe currently living in Canada. The examination revealed that members of these families found it more difficult to control their conduct, both with respect to themselves and their children, than a peer group. Other phenomena he reported included a higher incidence of quarrels and arguments between siblings than what was reported for a peer group; the parents’ particularly strong attachment to their children, and the children’s perception of their parents as extraordinary people. Sigal also carried out psychological tests on 144 children aged 8-17 from survivors’ families. The study encompassed healthy individuals as well as children admitted to the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal for neurotic disorders. The clinical control group consisted of 219 children from families which had not suffered Nazi German oppression. The most significant differences between the children from the examined group and the clinical control group were observed for the 15–17 age group, i.e. in pubescence. A characteristic feature of adolescents from the examined group was a sense of alienation, especially when with other family members, but not when among other members of their social group, followed by uncontrolled, aggressive behaviours and conflicts that could even give rise to destructive consequences for the family.

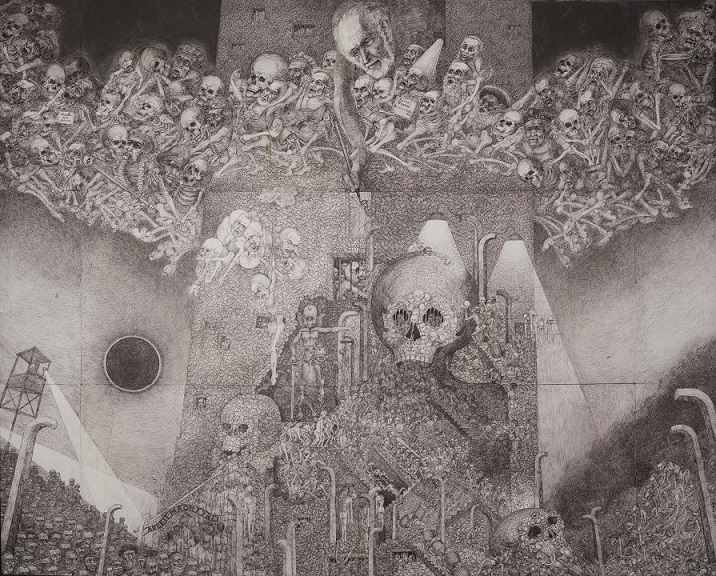

The Tower of Babel. Marian Kołodziej

The recent research presented at the 6th FIR International Medical Congress in Prague in 1976 included a noteworthy study by Edel, a Viennese,, who identified disorders among survivors’ children, evidenced by delayed pubescence and neurotic disorders in crisis situations (e.g. school, choice of an education and a career). These problems induced some of these children to run away from home or leave the country. Edel examined and treated the children. He stated that in these cases pharmacological and psycho-therapeutical treatment was not enough and advised close cooperation between the psychiatrist and the child’s parents, teachers and his supervisors at work.

Heftler, a French author from Paris, was interested in psycho-sociological research on survivors’ children born after their parents’ return from concentration camps. She asked a group of 50 people to answer a questionnaire. Some of her most interesting results include the following: 78% of the respondents said their parents were “different” from their friends’ parents, describing them as nervous and impulsive; 66% did not see themselves as any different from their peers, whereas 34% felt different but could not put it into words, though they said they had a sense of belonging to a “clan” of survivors and their families; 57% had a sense of pride because their parents were survivors, but 23% were embarrassed because of it, and 12% said it did not matter to them; 66% said their parents’ ordeal had an impact on their lives. Striving for social advancement was explicitly indicated in the statements made by children of Jewish survivors, whereas the feeling prevalent in children of survivors who had been imprisoned for their activity in resistance movements was a sense of pride.

Kahn reported adverse psychosocial symptoms in the children of Auschwitz survivors after examining a group in which she noted higher than average numbers of divorcés, individuals who stayed single (viz. remained unmarried) by deliberate choice, drug addicts and offenders who committed violence and theft.

Kempisty is one of the Polish authors who have been examining the issue (1973, 1975, 1976). The aim of his medical and sociological research was to answer the question on the extent to which survivors’ psycho-physical idiosyncrasies influenced the life and health of their children. On the basis of examinations and observation of 620 survivors and 346 replies to a questionnaire given by their children and 241 replies from their doctors, Kempisty and his associates observed the following: a high degree of social disorganisation in the families; for 42.2% of the children there were problems with upbringing due to excessive aggressiveness or timidity, emotional detachment, a poor school record, truancy and running away from home, juvenile delinquency and even theft. They also noted poor school performance and high rates of staying down at school as well as suicide attempts. For the small children, they recorded a high frequency of bedwetting, which was an indicator of childhood neurosis. Most of the doctors who responded to the questionnaire wrote that the main source of the neuroses of the children and young people in their care were the psycho-pathological conditions of their survivor parents due to their concentration camp past and its consequences.

My research

The research which I describe below relates only to people seeking treatment for neurotic disorders and represents the initial stage of a large research project which started in 1975 to determine whether there are any specific psychological traits in survivors’ children.

I examined four women and three men aged 20-28, all from the educated class families resident in Krakow. Both parents of one of my patients were concentration camp survivors, one of the parents of another five patients was a survivor, and the mother of one man had to spend the whole period of the Nazi German occupation of Poland in hiding because she was Jewish. Three patients had no siblings, the rest had either one, two, or even three brothers or sisters.

Three people were inpatients at the Medical Academy Psychiatric Clinic in Krakow, and four were treated as outpatients between 1973 and 1975. Four were diagnosed with both personality disorders and depressive neurosis or neurasthenic depression. Two patients were diagnosed with personality disorders only and showed no symptoms of neurosis, while one patient was diagnosed with neurosis only, with no personality disorders. Three were suffering from depressive neurosis and another three were diagnosed with neurasthenic depression, one was suffering from psychosomatic disorders as well.

All the patients I examined had high ambitions and wanted to be successful, but at the same time they were reclusive and had difficulties with establishing social relations due to social anxiety. Their emotional bonds were weak and few in number. They were lonely and felt the people around them did not understand them. They had a low self-esteem and problems in sexual relationships. These patients were very intelligent and had a lot of interests. Two of them showed symptoms of neurotic hyperactivity, engaged in difficult and dangerous activities to improve their low self-esteem. They sought intensive professional work and community activities to compensate for their emotional problems.

The remaining five patients decompensated very easily if they failed in an undertaking in education or their erotic relationships. Neurotic decompensation was usually a long-term process in these individuals.

Another striking landmark in the research was an observation of the children’s guilt complex with respect to their parents, particularly to the survivor parent. They were only partially aware of their sense of guilt. They saw this parent as a hero, whom they could neither match nor satisfy his or her expectations, which, by the way, were usually very realistic and achievable. Their sense of guilt was often accompanied by feelings of aggression, probably partially evoked by their inability to meet the expectations of the survivor parent and in part by the same parent’s excessive care and overprotectiveness, interference in the child’s personal matters, and patronising interventions whenever the child experienced a failure or a setback. Quite obviously, the child’s resulting reactions and aggressive feelings aggravated this sense of guilt (“my parent suffered so much, is so caring for me and I am such a bad child”).

Only one of my patients, a 28-year old woman, has managed to fulfil her ambitions without significant disruptions or serious difficulties with adaptation. One man has succeeded in completing his higher education and lives away from his parents with his wife and a child, but even he has not been able to become emotionally and financially independent of his parents.

The remaining five people still live with their parents and face difficulties with completing their higher education and are still socially, emotionally and materially dependent on their parents.

With the exception of one patient, all the people I examined were born in full families. Four families had an ongoing overt marital conflict between the parents that appeared to be conditioned by personality changes in one of the spouses (viz. the concentration camp syndrome). All the survivor parents had some personality changes, and four of them were periodically receiving psychiatric treatment.

Significantly, in the families with more than one child, mental disorders (neuroses or personality disorders) were diagnosed in the child with the strongest emotional attachment to the survivor parent. Also, in families with an only child, his emotional attachment to the survivor parent was much stronger than in the children who had siblings.

Two patients whose survivor parents focused on professional and community work after liberation and were constantly busy as if trying to make up for the years lost in the concentration camp showed more drive, resourcefulness and pugnacity than others. Conversely, the rest of the patients, namely children of survivors with clear signs of post-camp asthenia, decreased vitality and lowered mood, showed traits similar to those of the parent. They also had a very low frustration tolerance, were passive and withdrawn, and had long-term symptoms of neurotic decompensation.

Conversations about the reign of terror took place on a daily basis in the families of the examined patients, who had witnessed such talks from an early age. Consequently, it does not come as a surprise that three of the patients had nightmares related to the subjects discussed in these conversations. All the patients were very interested roughly until adolescence in topics related to the wartime occupation of Poland. Two of them continued to be interested in the subject in later life, while the rest experienced a radical shift in their attitude, manifested in consistently avoiding such topics in conversations, not watching films or reading about the Nazi German occupation of Poland. Five of the examined still show a distinct aversion to anything related to Germany.

To make things plainer for the reader, I will now present a summary of three of my patients’ medical histories (they concern two men and one woman). For obvious reasons, I have changed or omitted the personal data which could have disclosed their identities.

1. A 24-year old man, treated several times for mental disorders, neurasthenic and depressive neurosis and alcoholism. Both parents were prisoners of concentration camps. The relationship between the parents was good. The mother is in psychiatric treatment due to post-camp asthenia; she is overprotective of both of her children, born after her return from the camp, and especially of the patient, who is the younger child. On returning from the camp the father focused on professional and community work as if he wanted to make up with his hyperactivity for the years lost in the camp. The patient, i.e. the younger son, was given excessive care also by his father, who tried to protect him from difficulties and setbacks, endeavouring to handle even small issues related to the son thanks to his contacts with a community of survivors. The patient is characterised by timidity, striving for success; he was good at school, which pleased his parents, and showed artistic interests. He was very attached to his parents, especially to his mother, and competed with his sister for their love. The first symptoms of neurosis occurred when he went up to university. He tried various faculties but did not succeed in completing the first year in any of them. Periodically he took up jobs but was unable to adapt to his new environment. He felt a growing sense of guilt toward his parents, showed signs of depression and alcoholic tendencies, and isolated himself off socially. His self-esteem fell, although he had a high level of personal ambitions. He engaged in sexual relationships from the age of 19 and maintained a long-term relationship with one girl, which came to an end when he left for another city. Subsequently, he had a few short-term relationships which he considered unsatisfactory. Recently he has been on his own all the time, feeling insecure in relations with women. He was inoperative and undecided in undertaking action; he was inactive and his vitality was low. His behaviour was like his mother’s, namely passive-dependent and submissive. The prevalent conversation topic in this patient’s family home was the Nazi German occupation of Poland and camp survivors were frequent visitors. The patient was very interested in the subject of concentration camps, as evidenced by the subjects of his amateur artworks. He viewed his parents as heroes and wanted to be as courageous and determined as they had been.

2. A 26-year old man, treated both as an inpatient and as an outpatient for personality and anxiety disorders, with prescription drug addiction and intoxicant abuse. His mother is a concentration camp survivor. She still shows signs of a depressive syndrome nowadays and has been treated as an outpatient. She has always been overprotective in relations with her children, namely her son (my patient) and his younger sister. She tried to meddle in their affairs even when they grew up. The marriage of the patient’s parents was harmonious. During adolescence, the patient engaged in the hippie movement, which was on the rise at the time. He did this because he wanted to develop close emotional relationships with other people, as he had been a loner since early childhood, felt inferior to his peers, but was very ambitious. He had always been very timid, poor at speaking and nervous in new situations. He was hospitalised due to an overdose of drugs and finished school after his treatment. He started a course of higher education three times, but never managed to complete the first year, mostly because of excessive examination anxiety. Unable to complete his higher education, he took up a job, yet still dreamed of graduating from a university. He asked for outpatient treatment due to stuttering, excessive blushing, and a tendency to develop diarrhoea in social situations. He also suffered from frequent nightmares on subjects connected with the war he knew from his mother’s stories. As a child, he showed a keen interest in subjects connected with the war and concentration camps but gave up this interest in recent years. On one hand, he viewed his mother as a heroine and felt a constant sense of guilt for not meeting her expectations. On the other hand, he also had strong feelings of aggression to her for her over-protective attitude.

3. The sister of Patient 2., a 23-year old woman, treated as an outpatient for anxiety disorder. Her home situation was the same as her brother’s. Her first onset of neurotic symptoms occurred in the last years of high school and took the form of lowered mood, unmotivated anxiety, difficulties in establishing relations with other people, and vegetative symptoms. These symptoms prevented her from starting higher education in spite of her significant ambitions and high aspirations. She was able to develop a lively emotional relationship with a man, but it was not accepted by her mother, who tried to break it up and develop a sense of guilt in her daughter for not graduating from university and for taking a job below her intellectual capacity.

The psychiatric research I have conducted prompted a few ideas, which, nevertheless, could hardly be called hypotheses. Yet, perhaps they could serve as a starting point for further research on a broader scale to confirm certain regularities.

My research has led me to formulate the following questions:

1. Are there any particular personality traits in the children of concentration camp survivors which distinguish them from other young neurotic patients from families with no experience of wartime oppression?

2. Is the incidence of neurotic disorders more frequent in these children?

3. Do patterns and similarities between changes in the mental structures of survivor parents and their children really exist as these cases seem to suggest?

4. If so, does the basis for these patterns and similarities have its roots in an imitation or identification mechanism or in some other complex psychological mechanism?

5. Does a very strong, ambivalent emotional relationship with a survivor parent and long-term emotional dependence constitute an element characteristic for the mental structure of survivors’ children?

6. Does psychotherapeutic treatment for these patients require specific parameters as this is a controversial issue in the hitherto rather sparse psychiatric literature on the subject?

7. Finally, can we say that the psychological pathology of the parents resulting from their wartime experiences is reflected in the next generation and what is the transfer mechanism?

Translated from the original article: Dominik M., Teutsch A.: Nerwice u potomstwa byłych więżniów obozów koncentracyjnych. Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1978.

References

1. Blos, P. 1968. “Report on some experiences in a court clinic.” Paper delivered at the 1968 Convention of the American Psychoanalytical Association in New York (cited after 10.).2. Brody, G. 1971. “Analysis of a fugitive son.” Paper delivered at the 1971 meeting of the American Psychoanalytical Association in New York (cited after 10.).

3. Edel, E. 1976. “Zur Problematik der Behandlungsfähigeit der zweiten Generation.” Proceedings of the 6th FIR International Medical Congress, held in Prague, 1976.

4. Furman, E. 1971. “The Impact of Nazi concentration camps on the children of survivors.” Paper delivered at the 1971 meeting of the American Psychoanalytical Association in New York (cited after 10.).

5. Heftler, N.1976. “Étude sur 1’état actuel psycho-sociologique des enfantes nés apres le retour de deportation de leurs parents (pere, mere, ou les deux). ” Proceedings of the 6th FIR International Medical Congress, held in Prague, 1976.

6. Kahn, M.-L. 1976. “Les problemes de la seconde génération. ” Proceedings of the 6th FIR International Medical Congress, held in Prague, 1976.

7. Kempisty, C. 1973. “Wyniki socjo-medycznych badań potomstwa byłych więźniów obozów hitlerowskich.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 12–20 .

8. Kempisty, C.: 1974. “Stan zdrowia i losy dzieci — potomstwa byłych więźniów obozów hitlerowskich.” In Zbiór referatów wygłoszonych na II sympozjum naukowym komisji zdrowia Okręgu Warszawsko-Mazowieckiego ZBOWiD w Warszawie w 1974 r. Warsaw: ZBOWiD, 61–73 .

9. Kempisty, C. 1976. “Ergebnisse der soziomedizinischen Untersuchungen der Nachkommenschaft der ehemaligen KZ-Häftlingen.” Proceedings of the 6th FIR International Medical Congress, held in Prague, 1976.

10. Kerstenberg, J. 1974. “Kinder von Überlebenden der Nazivervolgungen.” Psyche 3, 249–256.

11. Krystal, H. 1968. Massive Psychic Trauma. New York: International Universities Press.

12. Laufer, M. 1970. “The analysis of children of survivors.” In The Children of the Holocaust Symposium, International Yearbook for Child Psychiatry and Allied Professions, Vol. 2. New York: Wiley.

13. Lipkovitz, M. H. 1974. “Das Kind zweier Überlebender.” Psyche 3, 231–248.

14. Rosenberg, L. 1970. “Children of survivors.” In The Children of the Holocaust Symposium, International Yearbook for Child Psychiatry and Allied Professions, Vol. 2. New York: Wiley.

15. Sigal, J.J., and Rakoff, V. 1971. “Concentration camp survival. A pilot study of effects on the second generation.” Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 16, 393–397.

16. Sigal J.J., Silver, D., Rakoff, V., and Ellin, B. 1973. “Some second generation effects of survival of the Nazi persecution.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 43: 3, 320–327.

17. Trossman, B. 1968. “Adolescent children of concentration camp survivors.” Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 2, 12 –122 .