Author

Wanda Półtawska, MD, PhD, born 1921, psychiatrist, Professor Emerita of the Chair of Psychiatry at the Kraków Medical Academy. Formerly Director of the Institute of the Theology of the Family at the Kraków Pontifical Academy of Theology. Ravensbrück survivor, No. 7709.

The psychiatric research we have initiated on the youngest prisoners of Auschwitz and the infants that were born in the camp is to establish whether those who spent their early years or months in Auschwitz have been mentally affected by their imprisonment, and to analyse the types of impact it has left on their personalities.

So far we have examined those patients who were under eight when the camp was liberated; the majority of these children were under five.

It is impossible to specify the exact number of children in Auschwitz. Witnesses giving evidence at the Nuremberg trial attempted to produce rough estimates; some of them referred to the number of prams that had been left in front of the crematorium. Also, at present it is impossible to determine beyond all doubt how many of the Auschwitz children still live in Poland. All the archives of the Auschwitz museum, which have been made available to us by the curator, give records of about fifty children, while more precise documents list thirty-eight (eighteen boys and twenty girls).

Our initial investigations helped us to define the scope of future research. As more and more materials emerged, several problems started to surface which needed to be examined from the psychiatric, psychological and sociological points of view. The first issue seems to be whether the camp imprisonment was a decisive factor in the children’s development, and how deeply it affected their lives. It is not our intention to delve into the camp experience of the children, which is familiar to the adult survivors anyway. For the sake of this analysis the duration of imprisonment is fairly irrelevant because the earliest camp experiences appear to be completely erased from the children’s memory. No survivor from this group can recollect what happened to him or her in the camp. Only two can offer vague memories of leaving the place; one says, “We saw a long bridge there,” and the other, “There were many of us and we were waiting.”

Generally, the children of Auschwitz were placed in orphanages after the liberation of the camp, and later adopted. Some were put in an orphanage while the camp was still in operation, and taken home by their adoptive parents even before the camp was liberated. The adoption was mostly an informed decision of the couples, most of whom were childless. However, there were also other cases, e.g. a young lad ran to the [liberated] camp and brought back “little sis,” who then stayed with the family.

The personality of the parents is definitely a decisive factor in shaping the child’s mind and fortunes. People who adopted the Auschwitz children tended to do so of their own accord; there was no pressure or disaffection to the children. The adoptive parents’ statements are sometimes movingly simple, but there is plenty of devotion behind this simplicity. One of the mothers, whose child is an adult man now, summed up her attitude to her son in the following way: “Well, perhaps I was too lenient, and spoilt him too much, but what I always had at the back of my mind was that this child had not had a mother’s tenderness and had gone hungry.”

The aim of our further analyses was to compare the Auschwitz children with a control group of adopted children in order to find out whether camp imprisonment proved an obstacle to forming a bond between the child and the adoptive parents. The preliminary findings are that the child-parent relationship was better than on average in families where the adopted children come from a regular children’s home. It seems that the parents, who had been aware of the child’s tragic past, were more patient and understanding towards the boys or girls who were not their biological offspring and often proved hard to manage.

The information concerning the earliest phases of development was usually provided by the adoptive parents or some other person in their environment because the children themselves tend not to remember the first months after liberation.

The analysis of the development of the Auschwitz children in this first period concerns both their physical and mental well-being. When the camp was liberated, all the children were cachectic (severely emaciated); some of them were extremely thin and seemed to weigh just as much as their bones, while others had oedemas. With all the children it was necessary to define their age arbitrarily on the basis of their medical examination. As it turned out, their actual age, which was discovered in a few cases later on, was higher, but had been miscalculated because of the weight loss. All the children had eye conditions, such as bacterial conjunctivitis or keratitis. Several mothers claimed that “some harm must have been done to their eyes.”

The children were suffering from boils, which was a common ailment in all camp survivors, and their skin was bruised, often along the veins, which again made the mothers repeatedly suggest that “their blood had been drained.”

Some of the children had bone or lymph node tuberculosis.

In almost all the cases the first months following the adoption meant a real struggle to keep the child alive. The mothers describe that period very briefly, saying that they were lucky to have managed to save the children and attend to them.

When the children were restored to health, they tended to develop normally. One may risk a statement that in a propitious environment they soon recuperated physically. A more complex aspect is their psychological growth and vestiges of the trauma in the nervous system, which was there for a very long time, and sometimes is still visible today. The early psychiatric symptoms always contained an element of anxiety. The medical histories of all the children invariably included one sentence: “The child was frightened, filled with irrational fear, mad with fear, ready to run for his life for fear.”

Initially, such reactions occurred both at night and during the day. The children were scared of the dark and night, loud voices, uniformed people and men in general, and sudden movement. The perplexing thing was that they were afraid to eat. When served a meal, they did not touch it, and instead waited for everybody to leave the room. Only then did they dare either to gobble up the food or, ignoring the plate, meticulously picked up crumbs from the floor.

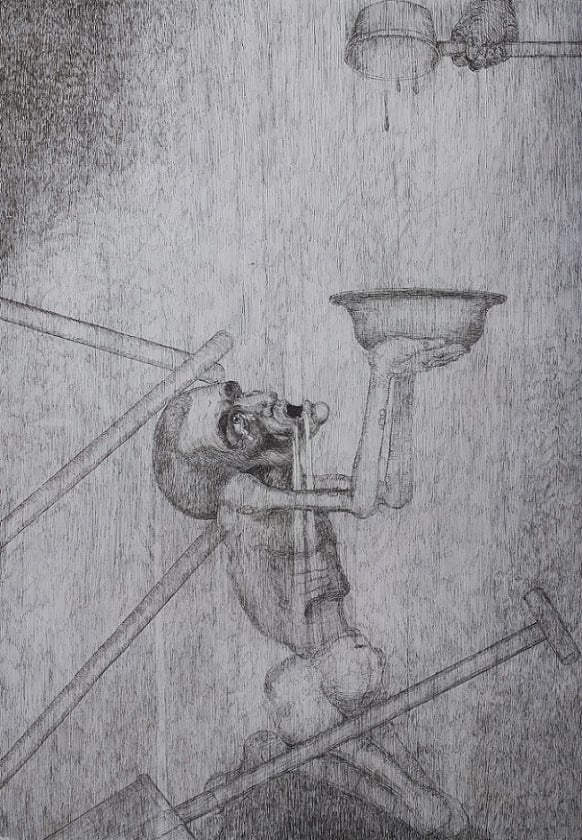

Request granted. Marian Kołodziej

When unexpectedly touched, the children would jerk and shout, or jump up and run away. In some of the older ones, especially boys, anxiety turned into aggression, so in the early days, when touched, they would hit the hand that had stroked them. On one occasion a five-year-old boy grabbed a gun and held it on any man he saw in a uniform. Generally, daytime anxiety was accompanied by the flight response: the children hid under the bed or the duvet, ran off anywhere, etc. At night, they woke up shouting and trembling. Some of the nightmares must have held glimpses of memories of the camp. The name “Mengele” was reiterated in sheer fright.

As for social relations, initially the parents concealed the fact that the child was an Auschwitz survivor, and even that their ward had been adopted. Yet, all the children very soon realised they were not the biological offspring of their adoptive parents, and knew they had spent their earliest years in the camp.

How the children received the fact that they had no parents is quite understandable, as a similar response is observed in all adopted children. The first comparisons with the control group show that the camp detention left its indelible mark on the subjects’ awareness. They seem to experience the question of their unknown origin in a more acute manner than those adopted children who did not have such a traumatic childhood.

When child survivors, now adult, are asked, “What do you know about yourself?” most of them unwaveringly answer, “Nothing.” Obviously, later on it turns out they do have some bits of information about themselves, yet they are overwhelmed by what is unknown.

Another conspicuous reaction, also connected with their unknown origin, is their attitude to Germans, which is much more aggressive than what we observe in adult survivors. In everyday contact this approach is not ostensible, but the subjects’ own reflections show they have a feeling of having been badly harmed, for which they put the blame on the entire German nation.

Of course, particular persons think differently about the fact that they are somebody else’s child. The majority learned about their time in the camp from the adults’ conversations, or sometimes from their school friends, especially when they were asked about the prisoner number tattooed on them. The youngest children had their number on their leg, so as they grew up, it became more and more obliterated and illegible.

An intriguing thing is that the children did not try to obtain any information about their biological parents. Whenever efforts were undertaken to find them, the initiative came from adults. When questioned, the young people said, “I was absolutely convinced none of my relatives had survived,” “If they were alive, they would have found me,” or “If they had survived, they would have been looking for me.” This last thought later turned out to be the starting point for the trauma-dictated response to their biological parents when found.

Different responses were observed to their imprisonment in the camp. Some children who continued to live in its vicinity sneaked out of the house to revisit the premises in order to look for “vestiges of their old selves.” And on the contrary, others preferred not to acknowledge their past. One of the children sat down and tried to recall his mother’s face. He recollected “she was pretty, with dark plaited hair.” From then on, this image visited the child’s memory and there was no way of knowing if he had really remembered his mother or if it was just wishful thinking. In their relationship with their adoptive mothers, the children displayed a typical attitude whenever they landed up in a conflict or were punished: “If you were my real mother, you would act differently.”

The awareness of being somebody else’s child hinders rapport in any family, also in the families who adopted the children in the control group, namely those who used to live with their biological parents or in children’s homes. This knowledge, however, did not seem to be a serious obstacle for the subjects, although there were misunderstandings, particularly between the children and the adoptive mothers. In general, there were not so many conflicts with the adoptive fathers, maybe because quite naturally they spent less time with the children.

Another issue is the search for the biological families. Auschwitz children, who are now growing up and settling down to run their own lives, studying or working, are encountering a new problem, which is also a source of conflict. After a turbulent adolescence, which either ruined or fostered the subjects’ relationship with their adoptive parents, we are witnessing a campaign, mounted by the press, radio, and television, to find those children’s biological parents. The subjects sum it up with a sense of injury: “Much too late.”

This response may throw some more light on the psychological and sociological aspects of developing a national identity. Some of the children’s parents have been identified, so now their origin is known. Yet, the conflict is still there, and it is even becoming more aggravated: the children do not want to be anyone else than who they have been so far. None of the Auschwitz children whose parents have been found have decided to change their nationality. Those who have been brought up in Polish families want to go on living in their social environment and they feel Polish.

The subjects reacted in different ways to the family search campaign. Some enjoyed the sensational aspect, while others were shattered to discover “that my mother’s not at all like what I thought she was.” What followed was disillusionment, regardless of whether the children found their biological parents or not.

With the new disappointment, the survivors felt a new grudge against their fate and the Germans. This obstacle was dealt with in various ways. Some subjects wrote open letters to newspaper editors, whereas others kept themselves to themselves, so as not to be disturbed. To onlookers, their experience is uncomplicated, but the subjects view it as a horror, sometimes saying, “I’d have to think what would be better.”

The family search campaign does not leave the adoptive parents unperturbed either, although appearances may be misleading. One of the mothers confided in a one-to-one conversation, “And yet I was shaken indeed to realise there is another woman she [the daughter] can call ‘mother.’” On the face of it, the adoptive parents are unaffected, but the relationships get tense. The young people’s thinking now follows a double course, which does not help them to lead a balanced life.

As this is a mental health paper, these preliminary remarks about our research so far should contain an assessment of the present condition of the Auschwitz children. Their traumatic past marked by incessant conflict, and the present, with its emotional double loyalty, work in tandem, increasing the subjects’ anxiety. Although none of them was diagnosed with any mental illness in the strict sense during their psychiatric examination, no mental health specialist who learns their biographies, hears their statements, or sees the results of additional tests can ignore the aspect of anxiety. All too frequently the subjects are described with phrases like “vulnerable,” “oversensitive,” “unlike other people,” “often deep in thought,” “looks away and seems to be somewhere else,” “hard to maintain contact with.” It is difficult to say whether all this can be classified as evidence of withdrawal, or perhaps something more serious.

Also, the results of EEG tests are deeply worrying. There is still not enough evidence to draw reliable conclusions, and the control group is too small. However, one is tempted to consider that the subjects’ course of life, and the traits that feature in other people’s descriptions may point to some serious damage that was caused, for instance, by starvation when the children were in the intense period of development. Nerve cells are harder to regenerate than other cells in the body.

The EEG tests show many abnormalities such as desynchronised patterns, infrequent slow wave activity, short theta rhythm patterns, irregular waveforms, temporal, frontal and generalised desynchronisation, and even sharp spikes recorded by various electrodes. To sum up, we obtain readings with characteristics indicative of moderate or acute pathology. It is impossible to determine if they are the effect of starvation, physical injury, or undiagnosed and untreated encephalitis. Nevertheless, we are sure those patients require special treatment, as they spent their earliest years in absolutely inhuman conditions, and this period in their lives proved to be highly detrimental and brought far-reaching consequences.

Our research is in progress. We are getting to know more and more Auschwitz children and facing ever more problems that should give us pause for thought.

Translated from the original article: Półtawska W.: Z badań nad „dziećmi oświęcimskimi” Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1965.