Author

Teresa Prekerowa, PhD, 1921–1998, a Polish historian, wrote about the rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust, honoured with the title of Polish Righteous Among the Nations in 1985.

Ethnic Poles started to help Jews as soon as the Germans began to make a distinction between these two groups of Polish citizens and to intensify their social and economic discrimination against the Jewish minority. Initially, aid was provided spontaneously, in individual cases, by relatives or friends who were “Aryans” in Nazi jargon. Jews were helped to stay in hiding and not to move out to the ghetto, or to obtain forged “Aryan” documents to rent accommodation or take up a job; some of them, especially children, found shelter in Polish homes; ethnic Poles tried to furnish their Jewish neighbours with provisions and money.

Soon similar attempts were being undertaken by the Polish underground political, social, and professional organisations. Their members, writers, journalists, and teachers, no matter whether their political sympathies were democratic, socialist, or communist, supported their Jewish colleagues and comrades, and their families, friends, and acquaintances. Practically every community could boast a team of brave and dedicated individuals who volunteered to take enormous risks, although Poland was growingly feeling the terror of German occupation, as its people faced the death penalty for giving food or lodgings to any Jewish person, and indeed more and more people were being executed for such acts.

As the War continued, aiding Jews proved to be an increasingly difficult task, if only for financial reasons. They were unable to earn a living for themselves, while all the resources they had stocked up diminished. The Poles were impoverished under Nazi German rule and found it harder and harder to share whatever they managed to procure.

1942 saw increased numbers of fugitives from the ghetto, who wanted to cling to life outside its walls, among the Poles. Mass deportations of Jews as well as rumours about the fate of those who were taken to Bełżec or Treblinka left no doubts: only those Jewish people could survive who could merge in with the general population.

At that time several centres of the resistance movement put forward a suggestion that a special organisation should be formed in order to help this neediest of communities, drawing upon Polish underground social funds, i.e. subsidies from the Polish government-in-exilea in London. In September 1942 the Government Delegation for Polandb (Delegatura Rządu na Kraj) endorsed the initiative and set up the Provisional Committee to Aid Jews (Tymczasowy Komitet Pomocy Żydom), most of whose members were Catholic or democratic activists. This body was headed by Zofia Kossak-Szczucka and Wanda Krahelska-Filipowiczowa and it dispensed aid to around 180 persons.

After a few months, in December 1942, the Committee was dissolved and replaced by the Council to Aid Jews (Rada Pomocy Żydom), codename Żegota, the members of which represented a wider social and political spectrum of Polish society. The chairperson was Julian Grobelny, aka Trojanc of the Polish Equality, Freedom, Independence Socialist Party (PPS-WRN), and his deputies were Tadeusz Rek (Sławiński) of the agrarian People’s Party (Stronnictwo Ludowe, SL) and Leon Feiner (Mikołaj, Lasocki) of the General Jewish Labour Bund. The treasurer was Ferdynand Arczyński (Marek) of the Alliance of Democrats (Stronnictwo Demokratyczne, SD), and later of the Alliance of Polish Democracy (Stronnictwo Polskiej Demokracji, SPD), when the former party split up. The position of secretary was held by Adolf Berman (Borowski) of the Jewish National Committee (Żydowski Komitet Narodowy, ŻKN). Other members of the board were Emilia Hiżowa (Barbara) of the Polish Democratic Organisation (Polska Organizacja Demokratyczna) and later of the Alliance of Polish Democracy; Ignacy Barski, and Władysław Bartoszewski of the Front for the Rebirth of Poland (Front Odrodzenia Polski, FOP), a Catholic social and educational organisation.1

Following its establishment, the Council to Aid Jews immediately set up its office, which was run by Zofia Rudnicka (Alicja) and Janina Raabe-Wąsowiczowa (Ewa); both of them were members of SD, and later of SPD. They were joined by two couriers, Celina Jezierska-Tyszko (Celinka) and Władysława Paszkiewicz (Władzia).

The mission of the Council was to support the Jews who lived in hiding outside the ghetto or were detained in slave labour camps. The Council’s charges were supported financially from funds provided by the Government Delegation for Poland, given ID documents to enable them to function outside the ghetto or camp, and offered accommodation or a hiding place. Jewish children were taken care of by Polish families and orphanages, both secular and ones run by religious congregations. Moreover, the Council endeavoured to foster favourable attitudes to get more people involved in dispensing humanitarian aid; it published underground leaflets with appeals to the Polish population, and sought to punish and prevent the activities of criminals who took advantage of wartime corruption to blackmail Jews in hiding. In order to accomplish such tasks efficiently, the Council’s board established special sections and appointed their managers.

The Council to Aid Jews did not set up its own local networks, but instead relied on the connections of those organisations whose representatives sat on its board, the more so that previously aid had been provided via their structures. In other words, the Council’s networks were based on those formed by PPS–WRN, SD, SL, FOP, ŻKN, and Bund, and several other individual groups, such as those who worked for the Bureau for Information and Propaganda of the Polish Home Army.

From the beginning, the Council wanted to operate not only in Warsaw, but also in other cities. However, it managed to create only two more branches, in Kraków and in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine) in the spring of 1943.

The Kraków board2 was chaired by Stanisław Dobrowolski (Staniewski) of PPS-WRN. The treasurer was Anna Dobrowolska (Michalska) of SD; the secretary was Władysław Wójcik (Żegota, Żegociński) of PPS–WRN. Its other members were Maria Hochberg-Mariańska, a representative of the Jewish community; Tadeusz Seweryn (Socha) of SL, and Jerzy Matus of ZMW Wici, a peasant youth organisation.

The Lwów branch had to work in the most difficult conditions because it had to reckon with potential reprisals not only from the German occupying forces but also from Ukrainian nationalists collaborating with the Germans. It was led by Władysława Larysa Chomsowa (Dionizy) of SD, and the treasurer was Przemysław Ogrodziński (Stanisław) of PPS–WRN. Though no formal board was appointed, the Council had dedicated supporters: Adam Ostrowski, as of March 1943 Lwów representative of the Polish émigré government; Justyna Wolffowa of PPS–WRN; Marian Wnuk; Artur Kopacz; Marian Pokryszko, and Adam Pokryszko.

It is estimated that the Council to Aid Jews provided financial welfare to about 4,000 persons in Warsaw, 1,000 in Kraków, and between 100 and 200 in Lwów (the available data give different figures). Many other Jews in hiding were beneficiaries of other kinds of aid.

The operations of the Council’s Warsaw branch are described in more detail in my book Konspiracyjna Rada Pomocy Żydom w Warszawie 1942–1945. Below I quote an excerpt to show the connections between the Council members and the Warsaw health service, and their joint effort to protect their most vulnerable dependants.

Providing medical aid to those who “looked Semitic” was an extremely taxing enterprise, as they were unable to go out into the streets outside the ghetto, or to make appointments in doctors’ or dentists’ surgeries. They always needed home visits, wherever they happened to be staying. Any medical tests or even surgical procedures that were necessary had to be arranged secretly, sometimes in primitive conditions.

If those who lodged Jews that ostensibly “looked Semitic” had no friends working in the health service, they found it almost impossible to provide any medical help. They were afraid to turn to strangers, realising that their attitude could be hostile, especially that some Poles [of German origin] registered as Volksdeutsche. Revealing the address where a Jew was hiding could have catastrophic results. On the other hand, even the most helpful doctor could be worried that a person requesting help for an ailing Jew might be an agent provocateur.

Even Jews sometimes failed to keep the security rules. Oblivious of the danger or completely dejected, some tried to be admitted to hospital, or went to see any specialist, sometimes immediately upon leaving the ghetto and with no “Aryan” ID documents on them. However, no cases are known of a doctor or hospital staff reporting such patients to the police or other German authorities. On the contrary, such Jews were given shelter and treatment, and put in touch with the necessary helpers. At the same time, they were advised not to act on an impulse next time, as the outcomes could be disastrous for them, the doctors, and any other parties involved.

Dispensing secret aid to Jews required adequate networks. The first underground organisation to set them up was the Joint Committee of Democratic and Socialist Doctors (Komitet Porozumiewawczy Lekarzy Demokratów i Socjalistów), established in the second half of 1940 in Warsaw. Its aim was to launch a resistance movement in the medical milieu and to counteract regulations imposed by the Germans which prohibited doctors from treating underground activists, those on the Gestapo’s wanted list, and Jews, both in and outside the ghetto.

Dozens of representatives of the medical professions were members of this Committee. Its regular operations were based on a system of threes. In each team of three doctors, only one could contact a higher-level threesome. The top-down arrangement was that each member of a particular team formed and supervised his “own” group of three, passing on to them the orders he had received from his superiors. In this way, each Committee member knew only five or six other members and, conveniently, had no information about the remaining teams and the Committee as a whole.

The Committee published its own, untitled journal, which was dubbed Alfabet Lekarski, literally “Medical Alphabet,” as subsequent issues were marked with different letters of the alphabet. Its editorial board of three comprised Dr Ludwik Rostkowski, an ophthalmologist, Dr Tadeusz Stępniewski, a dermatologist, and the leader of the team, Dr Jan Rutkiewicz, an internist. Its articles condemned the Nazi discrimination of the Jews: “The well-informed communities of Poles and Jews,” Ludwik Rostkowski Jr., a medical student, wrote in the spring of 1942, “should perceive each other as allies in their fight against the common enemy. In particular, they should stand up against the harmful anti-Semitic propaganda which is trying to lay scientific foundations for its dirty political and financial dealings [by accusing Jews of spreading typhus epidemics – TP]. A physician should see a sick person first and foremost as a human being.”3

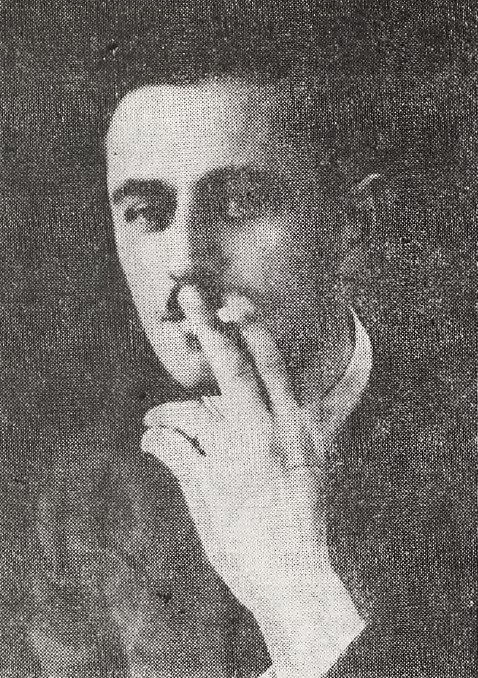

Fig. 1 Dr Ludwik Rostkowski (d. 1973), head of the medical section of the Council to Aid Jews

The Jews were helped not only by general practitioners, but also in several Warsaw hospitals, such as the Ujazdowski hospital, the Praski hospital, the Chocimska infectious diseases hospital, the Brzeska railway company hospital, the Kopernika children’s hospital, and others. Whenever possible, Jewish patients were admitted to isolation wards, which the Germans tended not to inspect for fear of contracting a disease.

From the very outset, the Council to Aid Jews wanted to facilitate contact between Jewish patients and doctors. Each team recruited its own doctors among friends, either of the members or of the Jews in hiding. For instance, Grobelny of PPS–WRN co-operated with Hanna Kołodziejska-Wertheim (who later became a professor of oncology) and Krystyna Staweno. The doctors who co-operated with the ŻKN team are listed in Barbara Temkin-Bermanowa’s diary.4 They were Dr Feliks Kanabus, Professor Stanisław Kapuściński (who died in Auschwitz as prisoner number 139007), Dr Kowalski, Dr Ignacy Oleśnicki, Dr K. Szalewska-Wojtowicz, Dr Stanisław Śwital, Dr Szczepan Wacek, and “Dr Tadeusz” (probably Dr Tadeusz Stępniewski). The fact that Bund established its own medical unit is recorded by Vladka Meed (born Fejgele Peltel).5 It “consisted of a few Polish and Jewish doctors, humanitarian enough to help Jews in hiding and provide them with medication. Dr Anna Margolis6 of Łódź was an absolutely exceptional person. Sporting a nurse’s outfit and a medical bag, she did not hesitate to visit even the most remote shelters.”

Other medical teams in the Council to Aid Jews, representing all the political organisations working for the Council, dispensed medical assistance in a similar way.

Also the youngest wards of the Council had their own paediatricians. Since the Jews who “had the wrong sort of looks” usually had to be hidden in crammed and dark premises, took no outdoor exercise, and were poorly fed, as the wartime provisions were meagre, “the children fell ill frequently,” wrote Irena Sendlerowa,7 an employee of Warsaw’s municipal department for welfare and social assistance, supervisor of the Council’s children’s section as of 1943 and distinguished for her service saving Jewish children. “Therefore we had to form a special medical unit. I would like to name some of its members: Prof. Andrzej Trojanowski, Prof. Mieczysław Michałowicz (whose home was always a refuge for people in need and who was helped by his daughter-in-law), Dr Zofia Franio from the Wola district of Warsaw, Dr Hanka [surname not given] from the Ochota district, and Dr A. Meyer from the Stare Miasto district. Sometimes it was necessary to take the children to hospital. They were treated by this group of doctors and nurse Helena Szeszko (Sonia), who was truly invaluable, as she had many useful underground contacts and was full of initiative.”

Other accounts of medical care for Jewish children add Dr Aleksander Landy and Dr Juliusz Majkowski to the list.

Post-war testimonies include the names of surgeons who performed foreskin reconstruction, mainly Feliks Kanabus and Andrzej Trojanowski (each performed about fifty such operations), as well as Prof. Józef Dryjski, Prof. Stefan Wesołowski, Prof. Janina Radlińska, and Leszek Aleksandrowicz, Tadeusz Baziak, Stanisław Białecki, Sergiusz Boruszewski, Stanisław Grocholski, Kazimierz Kozłowski, Józef Kubiak, Stanisław Michałek-Grodzki, Mieczysław Tylicki, and Wojciech Wiechno. Rhinoplastic operations (for nasal hump removal and nose shortening) were carried out by Edmund Mroczek, Dr Skórski, and Dr Staszewski, as well as a few of the surgeons listed above. Dr Grodzki and Dr Trojanowski performed otoplastic operations to correct protruding earlobes.

The doctor’s care had to be supplemented with equally risky and often equally necessary nursing care. The nurses tended to work anonymously, and the post-war recollections do not name many of them. However, we know that whenever a doctor who helped Jews was married to a nurse, she was involved in his mission too. Such was the case of Janina Rostkowska and Natalia Rutkiewiczowa.

It is clear that the list of physicians who used various connections to come in contact with the most threatened dependants of the Council was fairly long. At the same time, those Jews who did not have prominently Semitic features used the general healthcare system available to Poles. Yet the Council’s members were planning to set up a general medical unit to serve all the teams, to enable any Jewish patient or his carer to contact either a general practitioner or a specialist without unnecessary delay.

The plan was put into practice in the autumn of 1943. In the early days of October Ferdynand Arczyński (Marek) established contact with a representative of the Joint Committee of Democratic and Socialist Doctors, who promised his own and his colleagues’ gratuitous medical assistance. The Council’s board asked him to lead their medical section and appointed board associates Emilia Hiżowa (Barbara) and Celina Jezierska-Tyszko (Celinka) as his co-workers. All the involved parties met in the backroom of a restaurant in Warsaw’s Krakowskie Przedmieście. Although the Joint Committee’s representative was introduced only by his nom de guerre, Celinka immediately recognised him as Dr Ludwik Rostkowski, whom she had met before.

Dr Rostkowski accepted the position offered to him by Marek on behalf of the Council. Guidelines were formulated for the co-operation between the Council and the Committee, and they remained in force until the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising [on 1 August 1944]. They were as follows:

A few times a week Celinka checked all the dead letter boxes to collect messages from team leaders with the addresses and symptoms of Jewish patients. She passed the messages on to Lutek, that is Ludwik Rostkowski Jr., who delivered them to his father. Sometimes she sent copies to the board office as well. If the description was not specific enough to show what specialist was needed, Lutek saw the patient first, before notifying Rostkowski Sr.

Dr Rostkowski arranged regular meetings with Emilia Hiżowa to discuss general everyday business, usually in the room at the back of the restaurant. Sometimes there were other participants, the architect Romuald Miller who was one of the leaders of SD; and the brother of Tomasz Arciszewski of the right wing of the Polish Socialist Party. Often they brought information on patients in need of a home visit.

Once he knew which specialist was required, Dr Rostkowski dispatched him to the patient using the system of threes or contacting a Committee member directly. His son Lutek was of immense help, sending the doctors and nurses out as fast as possible.

Years later (in 1967), Drs Rostkowski and Stępniewski described their wartime work as follows:8

The participants in our mission were the following physicians: Kazimierz Bacia, internist; Jerzy Hruzewicz, neurologist (deceased); Feliks Kanabus, surgeon; Tadeusz Kaszubski, surgeon (deceased); Janina Krajewska, internist (died during the war); Jadwiga Pągowska, internist; Ludwik Rostkowski Sr., ophthalmologist; Tadeusz Stępniewski, dermatologist; Alina Przerwa-Tetmajer, surgeon;9 Ludwika Tarłowska, oncologist; Zofia Tyszkówna, gynaecologist; Andrzej Trojanowski, surgeon (deceased); Maria Wideman, internist (may still be alive); Helena Wolff (Dr Anka), internist (fought and died in a partisan unit); medical students: Ludwik Rostkowski Jr. (deceased), Aleksander Majda, and Mirosław Krajewski (who died during the war); as well as nurses Hanna Burakiewicz, Zofia Kryńska, Janina Lipińska-Rostkowska, Maria Pągowska, T. Romanowska, Natalia Rutkiewiczowa, Stanisława Trojanowska, and Maria Zachertowa.

What was needed during the visit was not only the usual doctor’s or nurse’s equipment, such as a stethoscope, syringes or dressings, but also medicines, and often clothes, food, and money provided by Żegota [the Council]. (...)

We had to pay very many home visits. Dr Rostkowski says the numbers oscillated between a few and dozens per month for each of the doctors. In some periods not a day passed without our doctors seeing “non-Aryan” patients.

On the basis of several testimonies, we can say that the medical unit worked efficiently, facilitating the work of the carers and assuring its Jewish patients that they need not worry if a health problem arose; they knew they would receive help from competent and devoted doctors.

On the other hand, there are no accounts of any large-scale, organised system of dental care. We know that individual dentists were approached when the need arose, and probably that satisfied the demand, as the matter was never discussed during a board meeting. Neither did it appear in the post-war memoirs of the people involved.

Jews who were provided for by the Council did not pay for doctors’ consultations or medications. Medical supplies were usually obtained from social assistance organisations recognised by the Germans, e.g. the Central Welfare Council (Rada Główna Opiekuńcza), or other institutions, such as the National Institute of Hygiene (Państwowy Zakład Higieny), where Zofia Kołodziejska, mother of Dr Hanna Kołodziejska-Wertheim, was employed. Other medicines had to be bought. The extant financial report of the Council for the last quarter of 1943 says that the medicines purchased for Jewish patients cost 10 thousand Polish zł.d

Treatment was just one of the forms of aid provided by the doctors. Importantly, they also issued several types of certificates, e.g. exemptions from obligatory typhus immunisation. Many Jews in hiding wanted to avoid the crowds during mass vaccinations, but if they did not present an exemption, they could not get food coupons and were likely to run into trouble. Also other Council members procured similar documents. For instance, the courier Sylwia Rzeczycka obtained dozens of them for people who were provided for by the team representing ŻKN. One of her acquaintances was a doctor who had registered with the Deutsche Volksliste but did not want to lose favour with her Polish environment.

Doctors’ help was indispensable to arrange for the “funerals” of people who had to go underground. The “burial ceremony” could take place only after a death certificate had been issued. Such documents were prepared by resistance movement doctors or the legalisation section of the Council, whose real task was to forge all kinds of official papers and certificates.

Fig. 2 Dr Tadeusz Stępniewski, one of the most active members of the medical section of the Council to Aid Jews

Finally, the doctors acted in their regular capacity to handle additional jobs such as distributing money or arranging clandestine meetings for members of the resistance movement. Their waiting rooms and surgeries were perfectly suited for that purpose because of the steady influx and turnover of patients. Especially Dr Stępniewski, one of the Council’s pillars, enjoyed a lot of freedom in this respect: he received patients in his parents’ spacious flat, located on Marszałkowska Street in the centre of Warsaw. Vitally, the building had four exits leading out into neighbouring streets, two into Moniuszki (through the passageways at Numbers 9 and 11), and two into Sienkiewicza (via the passages for Numbers 10 and 12 on that street). As Dr Stępniewski said goodbye to one patient and called the next one, in his waiting room he always saw the familiar faces of people who were charges of the Council. The courier girls used another stairwell and entered through the kitchen. One of them was Zofia Honowska, who always dropped by after meeting B. Bermanowa at St. Saviour’s Church to collect subsequent batches of allowance money. Another courier was Aleksandra Mackiewicz (daughter of the writer Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz), who worked for the Social Self-Defence Organisation (Społeczna Organizacja Samoobrony), FOP, and thereby for the Council. The money brought by these two couriers was promptly distributed according to the payroll to the individual Jews coming for their appointments, or delivered to those who could not turn up in person. The latter group included the wife of Adam Czerniaków, head of the Judenrat in the Warsaw ghetto. On 23 July 1943, hearing that mass deportations from the ghetto to death camps were imminent, he committed suicide.

In all probability, Tadeusz Stępniewski was not the only doctor to use his surgery in such a way.

The information I have presented does not do full justice to the self-sacrificing dedication and courage these Varsovian doctors had to show to save the lives of those who were humiliated, discriminated against, and doomed to perish under the Nazi German occupying regime. I have only described the systematically organised aid offered by Polish organisations. Yet there were other helpers who worked individually, of their own accord. Several recollections in the volume Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej (“He is my compatriot”) name professors of medicine like Rajmund Barański, Stanisław Popowski, and Maria Wierzbowska, and many other physicians, such as Drs Witold Horodyński, Franciszek Litwin, Wiktor Orzechowski, Paweł Szaniawski, and Dr Więckowski, who moved to Warsaw from Lwów. The 1942 summer issue of Abecadło Lekarskie says:

On 21 July 1942, (...) Professor (Franciszek) Raszeja was killed while performing his duty. He was an eminent scientist [who worked at the University of Poznań before the war – TP]. His achievements and dedicated work for the community brought him the respect and recognition of academia, his colleagues, and patients. (...) On that ill-fated day he was summoned to see a sick person in the ghetto and during the examination he, his patient, and some Jewish doctors were killed by Nazi German thugs [actually the victims were Prof. Raszeja, his patient Abe Gutnajer and his family, a nurse, and another Polish doctor – TP]. He died a doctor’s death.

The medical staff not only of Warsaw, but also of other Polish cities showed their solidarity and simple human kindness to their Jewish fellow-citizens. As yet, no in-depth studies are available on this subject, though the situation in Kraków has been described by Professor Julian Aleksandrowicz in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.10

Under the German occupation of Poland, doctors were one of the most oppressed professional groups. It is estimated that as many as 39% of them were killed,11 and the figure is so high because a considerable proportion of the medical profession (as well as the legal profession) were Jews. Yet among those who died there were also ethnic Poles, including doctors tending to Jews in hiding. In some cases, though any estimates would be risky, those activities must have been the grounds for their arrest, deportation or execution. Professor Franciszek Raszeja was definitely no exception.

Translated from the original article: Prekerowa T.: Pomoc lekarska ukrywającym się Żydom (w Warszawie, 1942—1944) Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1983.

Notes:

a. The wartime Polish government-in-exile left the country after Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded the country (1 and 17 September 1939 respectively), and operated first in France and (after the fall of France in June 1940) in Britain.

b. The supreme administrative body appointed by the Polish government-in-exile to operate secretly in occupied Poland.

c. All noms de guerre are given in brackets after family names

d. The German authorities continued to use the pre-war złoty currency on occupied Polish territories (the Generalgouvernement). The 500 zł. note was the standard payment for all manner of corrupt deals. See Piasecki, W. 2017. Jan Karski. Jedno życie. Warszawa: Insignis. See also entry "młynarki" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C5%82ynarki.

References

1. There were some personnel changes in the Council during the last months of its operations, but they had no significant impact on its work. I have presented the history of the Council to Aid Jews and its structure in my book entitled Konspiracyjna Rada Pomocy Żydom w Warszawie 1942–1945, published in Warsaw in 1982.

2. A comprehensive account of the Kraków branch of the Council to Aid Jews is presented in Tadeusz Seweryn’s article “Wielostronna pomoc Żydom w czasie okupacji hitlerowskiej,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1967, 162–183.

3. Quoted after Bartoszewski, W. and Lewinówna, Z., 1969, Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej. Polacy z pomocą Żydom 1939-1945. 2nd edition, Kraków, 243. The book includes more information, written down by L. Dobroszycki, on the Joint Committee of the Democratic and Socialist Doctors.

4. Temkin-Bermanowa, B., Dziennik podziemia, quoted after Mark, B., 1959. Walka i zagłada warszawskiego getta, 2nd edition, Warszawa, 164.

5. Meed, V., 1972. On Both Sides of the Wall. Tel-Aviv, 267.

6. Anna Margolis was a doctor and ŻKN member, who found a safe home with Stefania Sempołowska.

7. Ten jest z ojczyzny mojej… , 136–137.

8. Ibid., 153.

9. This piece of information about Dr Alina Przerwa-Tetmajer must refer to an earlier period, because on 21 July 1941 she was arrested, and deported to Auschwitz on 5 October 1943, (Domańska, R. 1978. Pawiak – więzienie gestapo, Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 339 and 359).

10. “Ludzie służby zdrowia w okupowanym i podziemnym Krakowie,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1963: 129–134. Other issues present biographies of some of the doctors mentioned in this article, that is Prof. Mieczysław Michałowicz, Prof. Franciszek Raszeja, Dr Kazimierz Błażej Bacia, Zofia Franio, Helena Wolff (Anka), and Janina Zachariasz-Krajewska.

11. Cienkowski, W. 1962. Straty wojenne Polski w latach 1939–1945. Poznań and Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Zachodnie, 90.