Author

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English.

As yeta. there has been no biography of Dr Janina Kościuszkowa, a woman who was much appreciated and widely known not only in Kraków but also in other circles before, during and after the War. She was an exceptional individual, with a strong character, firm moral principles and a special ability to face adversity. These characteristics proved useful during the German occupation of Poland, especially when she was imprisoned in the Montelupich jail and in several concentration camps. That’s why I am focusing on this episode of her life. The delay in writing her biography was caused by difficulties in finding sufficient sources. I had to limit myself to indisputable information and material which would allow me to depict the personality of Dr Kościuszkowa as well as to show the background to her activities.

In her written and oral accounts of topics concerning concentration camps, Dr Janina Kościuszkowa depicted the camp situation and other people in a vivid and precise way, but when she described her own experiences she was very brief, which came from her innate modesty. Her publications do not contribute much to her biography—they are not very autobiographical.

If you set out to write potted biographies of the medical doctors who were prisoners in the Nazi German concentration camps you could limit yourself to presenting the bare facts, as often happens when you don’t have suitable source materials and documents. But then you would lose the rich background as well as the particular ambiance and atmosphere of the reign of terror in the camp; you would also miss the psychological aspects of prisoners overcoming this terror, which showed that these physicians testified to their calling and became legends in the annals of history. Accordingly, it is important to make a moderate amount of reference to the usually unpublished stories and recollections witnesses have related. If you consider this deeper background you may unearth invaluable, more general ethical and moral values.

Janina Kościuszkowa, daughter of August Aydukiewicz, was born in Chrzanów on 17 May 1897. She graduated in Medicine from the Jagiellonian University Faculty of Medicine in 1924. After graduating she worked as a school doctor and taught hygiene in various schools in Kraków, including S. Münnichowa’s Girls’ School, a private lower secondary school located at ulica Andrzeja Potockiego (now Westerplatte) 11. She decided to become a paediatrician. She married the renowned judge Adam Kościuszko. They had a son Wojciech, born on 1 August 1927, who like his mother became a medical practitioner (he graduated from the Medical Academy of Kraków in 1952).

Before the War Dr Kościuszkowa ran a nursery that belonged to the state‑owned alcoholic spirits factory in the Kraków district of Dąbie. One of her colleagues at work was the nurse Janina Boguszowa (wife of Prof. Józef Bogusz), who not so long time ago spoke about her work with Dr Kościuszkowa (Boguszowa died in 1980). Dr Kościuszkowa continued to work in this nursery during the War, before her arrest, and her boss was a German, Dr Kammerer, originally from Austria. She got on well with Dr Kammerer, as he was an exceptionally moral person and kind to the Polish employees. Despite these good relations Dr Kościuszkowa did not avoid being arrested. She described her arrest, investigation and period in prison in her report entitled “Przez rok w więzieniu Montelupich” (A year in the Montelupich Prison; 1972). Below are some details concerning her prison experiences.

The Gestapo arrested her on 22 February 1942 when she entered the apartment of Dr Ernestyna Michalikowa, ill at the time, at ulica Grodzka 52. The Gestapo had set up a kocioł (decoy) in the flat and had already trapped some forty people who had walked in, and they were still waiting for more victims. Two hours after Dr Kościuszkowa’s arrival the German police began transporting the nearly 80 people who had been caught in this flat to their headquarters on the Pomorska street. As Kościuszkowa reported, “in the Gestapo headquarters we had a baptism of fire—a short interrogation accompanied by yells and violence. Late at night we were transported to the Montelupich Prison and crammed two or three people in a cell. After two days we were allowed to have a bath and disinfection. The arrested women were sent to the Helclów old people’s home, which the Germans nicknamed the Frauenkloster (nuns’ convent) and turned its basement, ground and first floor into a women’s prison.”

Dr Kościuszkowa was put in cell 39, together with 36 women who had just been arrested, in extremely primitive conditions: little space, cold, hunger, lice, and no water, soap or combs. These conditions have been described in many publications. The other inmates included Dr Maria Żebrowska, Ludwika Bormannowa (from Warsaw), Pelagia Lewińska, Helena Fikowa, and afterwards Stanisława Jamroz. Life in this cell was made even harder for them because of the presence of a group of prostitutes suffering from venereal diseases. A big help for them—also from the psychological point of view—came from the food packages delivered by the Patronat (Patronage) Society for the Care of Prisoners and the Rada Główna Opiekuńczab. (Central Welfare Council), thanks to the efforts of Maria Zuzulowa and Zygmunt Klemensiewicz.

Ludwika Bormannowa confirmed Kościuszkowa’s testimony, adding in her letter of 17 November 1978, “I only think that Dr Jankac. Kościuszkowa’s article should be supplemented by facts which she herself omitted completely. Namely, the specific atmosphere that she created in our cell. She was our authority from the very beginning, even when she held no special function. When new prisoners entered the cell, most of them, particularly those from Kraków, recognised Dr Kościuszkowa, who stood in the middle of the cell. As soon as they saw her they were at ease, and a smile lit up their faces. Dr Kościuszkowa acted as our ‘hostess’ and managed to introduce the newcomers to the other inmates in a very tactful way. She was not leader of the cell, yet she organised various activities, assigning responsibilities to maintain order and hygiene, which was very important not only for the sake of the hygienic conditions in the cell and also to keep the inmates in good spirits.”

There is also a description of Kościuszkowa’s attitude to inmates in a letter I received from Stanisława Jamroz, who was full of admiration for Dr Kościuszkowa’s efforts to get her companions out of their depression, and stressed her skill in using all the available means to activate them, first of all to keep the cell tidy. She encouraged the inmates to clean the floor, beat the blankets, catch fleas and lice; she examined the hair of the newcomers and, if needed, used Sabadil vinegar as a delousing treatment; she even badgered one of the young women into cutting off her plait because it was infested with lice; and she let other prisoners use her soap.

Dr Kościuszkowa remained in the cell until Dr Szczepan Kruczek, also a prisoner, managed to get her out. When he learnt that there was a medical practitioner imprisoned in that cell, he called for her help on so many occasions that the Gestapo eventually agreed to make her his deputy. When Dr Kruczek was deported to Radom prison, she was appointed physician both for the Frauenkloster and for the main building of Montelupich prison. Then she managed to get journalist Ludwika Bormannowa, a fellow‑inmate from cell 39, a job as a qualified nurse. So once she improved her own lot, Dr Kościuszkowa thought of her fellow‑prisoners and did her best to help them.

Dr Kościuszkowa tried to remedy the primitive conditions and appalling shortages in the outpatients’ casualty room by applying a variety of activities to compensate for the lack of ordinary hospital treatment. She made soothing wraps for bleeding wounds caused by torture. Sometimes she managed to get altacet (aluminium acetotartrate) disinfectant for patients. She gave pain relievers to prisoners who had been beaten during an interrogation. She also managed to persuade patients that their pills were far more effective than they were in reality. In fact, Dr Kościuszkowa’s most effective treatment was the psychological influence she had on her patients—her kindness, her smile, generosity, cheerful disposition and sensitivity. Although she was a paediatrician, she sometimes had to serve as a midwife delivering a baby at night, in darkness and in the worst conditions. This was the situation in which she attended prisoner Maria Kopeć’s labour.

Dr Kościuszkowa used subterfuge to get extra food for patients, for example by bringing them porridge which “needed to have fish‑bones removed from it.” She managed to keep those prisoners under interrogation in the hospital ward for a few days, to give them a respite. Whenever she wrote prescriptions for medicine which was to be supplied by Patronat chemists, she passed information on about prisoners’ health problems. As Stanisława Jamroz recollected, when she prescribed a bellyband she was in fact informing them that one of her patients was pregnant.

In her account of 19 April 1971 Bormannowa recalls that “Dr Kościuszkowa set up an outpatients’ clinic in a small room. Later she managed to obtain another room for her patients. Of course this was still not enough, and there were only a few beds in these rooms, but what counted was that there were some beds for sick prisoners to lie down on, and not on straw mattresses on the floor—and in the cells it was two prisoners for a mattress. The beds brought them some relief. But we had a shortage of medicines. . . .” The Central Welfare Council and the Polish Red Cross supplied medicaments, but not very much.

As Dr Kościuszkowa’s “nurse” Bormannowa wrote, she could go to the cells, find the sick and those who needed medical advice, and “craftily” bring them to the outpatients’ clinic. She dispensed medicaments, applied cupping glasses to their skin, washed them, treated their wounds, put on soothing wraps and provided extra food for the most starved. She heated food up on an electric cooker hidden in a large wardrobe. The prison cooks brought food in from the kitchen. Bormannowa witnessed Dr Kościuszkowa’s daily routine. For example, she remembers how Dr Kościuszkowa saved the life of Krystyna Makowska, who was lying on her stomach because she had been beaten up so brutally that her buttocks were lacerated. Kościuszkowa used a boiled rubber tube from the gas cooker to drain off the pus.

Dr Kościuszkowa treated patients in the Montelupich Prison three times a week. The outpatients’ clinic was run by Aleksander Bugajski, a young prisoner whom the Germans regarded as a sports physician. Bugajski was a clever and courageous Kedywd. agent. He and Stanisław Marusarze. were famous for their successful escape from the Montelupich Prison; later he was shot and wounded by the Gestapo and re‑arrested. Dr Kościuszkowa was admired in the Montelupich prison for her friendly and cordial attitude as a physician and companion, especially to her patients. After the War survivors and former prisoners remembered her for her courage. In her book Za murami Monte (Behind the walls of Montelupich) Wanda Kurkiewiczowa wrote laconically, “Kościuszkowa saved many prisoners’ lives.”

On 26 February 1943, after being imprisoned in the Montelupich for a year, Kościuszkowa was sent to Auschwitz‑Birkenau. She arrived at the camp with 62 male and 43 female prisoners. Her camp number was 36319. Danuta Czech noted in her Auschwitz Chronicle 1939–1945 that this was the time when the first transport of Roma from Germany arrived in Birkenau. At this time RSHAf. deportation trains were bringing Jews from Berlin who were sent straight to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived on the ramp.

So when Dr Kościuszkowa arrived at Auschwitz, the situation in the camp was especially tense. Her first days in Birkenau must have been a tremendous shock. This is how Danuta Czech described those days in the Auschwitz Chronicle:

“At 3:30 p.m. [28 February 1943, two days after Kościuszkowa’s arrival—author’s note] there was a general roll call in the Birkenau women’s camp. Work stopped in the whole camp. The order also applied to the camp hospital, but patients were to stay in their beds, while the medical staff and assistants attended the roll call in the camp. First all the prisoners were made to stand in rows in the order of their numbers and then they were sent out to the meadow adjoining the camp. Each prisoner’s identity was confirmed as she went through the gate. In the meadow they were made to stand in columns of 200. During the roll call around 1,000 Jewish women were selected and sent to their deaths in the gas chambers. The roll call ended at 5 p.m. and the prisoners were commanded to run back to the camp. The old, sick and weak prisoners who could not run were pulled out with sticks. All of the prisoners who were pulled out were directed to Block 25 in the women’s camp and subsequently transported on lorries to the gas chambers.”g.

The mortality rate in the camp was very high; for instance, the underground resistance network in the camp estimated from 1 to 28 February 1943 a total of 3,094 tattooed female prisoners were killed in Birkenau, 1,690 of them were gassed, not counting the unregistered victims sent to the gas straight from the train ramp.

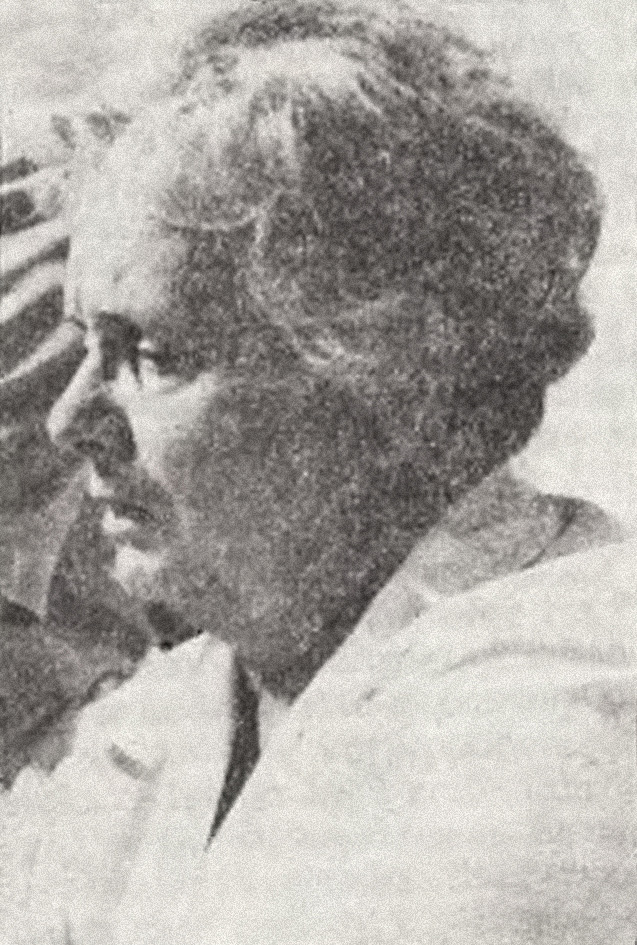

Dr Janina Kościuszkowa

Dr Kościuszkowa’s name appears quite frequently in the literature on the camp, both in the published texts and manuscripts. One of the prisoners of Birkenau was Dr Stefania Kościuszkowa, who did not survive. Her sister‑in‑law Janina Kościuszkowa wrote a brief memorial for her published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim in 1961. The two women were related by marriage. A typical observation on Janina Kościuszkowa occurs in Janina Komenda’s typescript: “Dr Janina Kościuszkowa from Kraków, a medical practitioner from the diarrhoea block (No. 20), evacuated to Dresden in a trainload of patients; after the War head of the Kraków home for infants.” She is also mentioned in many books on concentration camps, including Józef Garliński’s book, in which she is on record as a courageous doctor working with the camp resistance movement.

Straight after arriving at Birkenau, Kościuszkowa was assigned to the Auschwitz I camp to work in the Stabsgebäude (staff building), which was located outside the men’s camp on the site of the former tobacco factory. Very little has been written about this aspect of the camp. So on the basis of my correspondence with Zofia Burghartowa, one of Kościuszkowa’s fellow‑inmates, I shall explain that the staff building housed female prisoners employed in the Politische Abteilung (political department). In its basement there were rooms for the SS‑Wäschereikommando, a group of about 40 female prisoners who did the SS‑men’s laundry, and for those working in the ironing room and sewing facilities, for women employed in Bauleitung (the construction management office), for Jehovah’s Witnesses who cleaned the SS‑men’s accommodation located outside the camp, for the manicurist and hairdresser who performed services for the SS female guards, and for a few Polish women who cleaned the accommodation of the guards living upstairs, over the female prisoners’ quarters in the basement and the premises where Kościuszkowa, Burghartowa and other women worked. All these female prisoners could use a small hospital room with nine beds for patients and one bed for Kościuszkowa, who was the inmate doctor here from February 1943.

Józefa Kaleta‑Kiwała (No. 6792), a prisoner in this Kommando, wrote of this camp hospital that “only female prisoners with minor illnesses such as a cold [rhinitis] or a sore throat could stay there. Those diagnosed with contagious diseases had to be sent to the hospital in Birkenau right away.” Kiwała describes Kościuszkowa’s attitude to patients in the staff building: “She was absolutely devoted to her professional work and saved the lives of many inmates. Although the SS physician often came to supervise her, she took risks which could have meant serious consequences for her. If she diagnosed a case of typhus, she entered a fake disease on the patient’s medical card or hid the sick woman in the main ward before the SS‑doctor arrived, to save her from being sent back to Birkenau.” Another survivor who confirms this is Burghartowa, who writes that Kościuszkowa saved patients from death selections by falsifying the results of their medical examinations and recording fake diagnoses, and that she was not afraid of the consequences should any of the German prisoners or SS hospital personnel catch her at it. Death took a heavy toll in the Birkenau hospitals due to frequent selections and the extremely primitive conditions.

Moreover, Kiwała recollects that when Dr Kościuszkowa was working in the staff building she was in regular contact with the inmate doctors and pharmacists from the men’s camp, and thanks to that she got and smuggled medicines into “her hospital,” drugs that were hard to obtain in the camp, for example Weigl’s anti‑typhus vaccine. From the very beginning of her imprisonment in the camp she enjoyed the reputation of an inmate who was courageous, helpful, resourceful and willing to bring relief and comfort to fellow‑prisoners. Her whole attitude helped her distance herself off from the horror of the camp. However, her inmates noticed that she was worried about the fate of her husband and son, who were living in Kraków.

Kościuszkowa’s work in the staff building did not last long. Alina Przerwa‑Tetmajer, another prisoner‑doctor, explains why she was transferred to Birkenau. Przerwa‑Tetmajer also describes Kościuszkowa’s appearance:

“Janka was punitively removed from the Stammlager (main camp) and sent to Birkenau for her illicit medical help (she administered injections using drugs smuggled into the camp in parcels etc.). Despite the hunger in the camp, her rather stout figure did not fit in the striped prison gear which she had been issued in the Central Sauna. I saw her trembling with cold and terrified, but her big blue eyes were still smiling as she said, ‘I am happy that here I can look after the children.’ She knew that there was a children’s block for those deported from the Zamość region. The first thing I managed to procure for her was a big pair of bloomers made from a blanket. Those knickers entered the annals of history, as in her recollections of the camp, Janka never forgot to mention that the most wonderful present she had ever been given were those unmentionables: ‘you saved my life, for I felt I was dying of cold, and when I put on those bloomers I came back to life. I felt that I was a doctor again and not a fagged out prisoner.’”

In her brief, unpublished account Dr Irena Białówna mentions Dr Kościuszkowa’s sudden transfer to Birkenau and her own part in Kościuszkowa’s placement in the camp hospital. Białówna was struck by Kościuszkowa’s appearance, so very untypical for the camp. She was obese and had wavy hair, which made her very different from other inmates, who were emaciated and had shaven heads. She was sitting on a stool in the outpatients’ room, dozing and very tired. She was assigned to work in Block 22, to look after German inmates. Although this job helped her survive, it did not last long and made her sad, as she could not help her compatriots. However, this changed when new female prisoners and children arrived from Warsaw after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising.

In another unpublished note, Dr Irena Białówna wrote of Dr Kościuszkowa’s arrival from the staff building:

“I remember how pale Dr Kościuszkowa was when she was being registered in Birkenau. She did not want to talk about her job in the main camp. She did not go into details and just said that in general it had been very tiring. Her transfer to Birkenau was very sudden: she was called out and ordered to collect her things, not knowing where she would be taken. In Birkenau she was brought to the women’s hospital and accommodated in the outpatients’ facilities. . . . I woke her up and remembered I had promised Dr Michalikowa that I would help Kościuszkowa; unfortunately, in the camp conditions my help was limited to introducing her to our team, especially those who had better jobs or important friends, and I helped her settle in. Presumably thanks to her reputation as a good medical practitioner and her fluent German she was sent to work in the German inmates’ block.”

Alina Przerwa‑Tetmajer confirms that Dr Kościuszkowa was assigned to the block for anti‑social German prisoners (i.e. criminals, prostitutes, etc.), adding that “the block got somewhat better treatment from the SS‑men. Thanks to her fluent German, Janka often managed to obtain better food or medicines that would be smuggled into the children’s block.”

Dr Ella Lingens, a German prisoner‑doctor and a friend of Dr Kościuszkowa’s in the camp and after the War, remembers her very well. Lingens recollected their stay in the small room shared by several doctors (Irena Białówna; Jadwiga Hewelke; Ernestyna Michalikowa; Ella Klein, a Jewish doctor from Prague, and others). Dr Kościuszkowa occupied the lower bunk because of her weight (“well, she was not a lightweight,” Lingens wrote in her letter). Lingens made friends with the other prisoner‑doctors who worked in Block 9 (the convalescent block), but quite slowly because of language problems. The Polish doctors spoke Polish to each other and Czech with Dr Klein. They didn’t like to speak German. After a few weeks Dr Lingens had picked up some of the basic words and expressions in Polish from her Polish colleagues and patients.

Lingens says that Dr Kościuszkowa was the first Polish woman who got across the barrier of distrust. They shared the bread and food from their parcels. In her letter Lingens writes how she ventured on her first sentence in Polish: “Tonight we will have your onion and tomorrow evening it will be my onion,” spelling it “phonetically,” as she didn’t know how to write it in Polish. She adds that “Then Dr Kościuszkowa and all the other doctors hugged me and said that I had been admitted into the Polish doctors’ group, and they were happy that I had made an effort to learn their language.” She tried to learn the basic Polish vocabulary. Her Polish fellow‑inmates corrected her, while Kościuszkowa comforted her, saying that she spoke Polish like a baby trying to be understood.

Lingens remembers that she learnt a lot from Kościuszkowa’s experiences of solving various medical problems, e.g. making diagnoses: “what was wrong with one of my female patients. Who would have thought that adults could contract children’s diseases like measles or scarlet fever, which could take a very severe form in the camp.”

Basically, Dr Kościuszkowa treated adult inmates, but when she left the hospital block she also treated children. Alina Przerwa‑Tetmajer remembers this, and says that “the children of Auschwitz had to thank Janka not only for food—she kept hunger away from them—and for medical care, milk and medicine, but also for her smile, since she made them smile on the many occasions when she brought them clothes and toys. Besides her regular, 12‑hour daily work shift treating adults, Janka examined all the sick children. She smuggled in mitigal, which was very difficult to get, trying to keep children from catching scabies. Janka loved children, and she loved them all her life. She made accurate diagnoses of their illnesses without any auxiliary tests or X‑ray examinations. She suffered when she was not able to help them in the camp conditions.”

Caring for children imprisoned in Birkenau was very hard. She managed to meet only some of their basic needs since, as we know, the SS‑men’s policy on children was outright extermination. Saving children, by means which were either partly or completely illicit, required solidarity and the joint effort of adult prisoners committed to the task and brave enough to risk their lives. I shall quote Dr Kościuszkowa’s article in one of the 1961 issues of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (this issue is practically unavailable nowh.):

“[O]ut of the blue large transports started arriving at the camp from the insurgent Warsaw: old women and babies, children and adults. Again, the children were separated from their mothers. Two brickwork blocks, those with the worst living conditions, were used for them. Three hundred children were accommodated in each block; ten to a bunk, so it was dark inside, as there were so many of them. Dirty, hungry, poorly clothed, tormented by the experience of the Warsaw Uprising and a long journey of several days, they started to contract diseases: pneumonia, scarlet fever, diphtheria. A tiny hospital room was arranged: 2 m x 3 m with two three‑storey bunks with 3 or 4 children on one bed.

“As the number of the sick children was steadily growing, they were accommodated in the hospital block for adults. No bedsheets and nowhere to do the laundry; no baby smocks or warm clothes. Our efforts would have been futile if it had not been for the inmates’ help. They brought us whatever they could spare, not only clothes; they could even turn up with a bucket of nourishing soup or fruit and vegetables that they had ‘managed’ to get working outside the camp . . .”

Let me quote Dr Kościuszkowa’s account published by Wanda Zakrzewska in her article (the reference is in the list of sources):

“The hospital block was out of bounds; it was surrounded by barbed wire. Prisoners were generally not allowed in. But what wouldn’t our inmates have done to overcome all the obstacles and barriers just to see and support their relatives or friends! There were two categories of patients: those who required immediate treatment, and those who were completely emaciated, tired, and weak: for them staying in the camp hospital was a respite from their strenuous labour, from long roll calls up on their feet—it was a time to recuperate their health and save their life. This was true especially of the older inmates, those over 50, knocked out completely by the unbearable toil and camp conditions. It was very difficult to admit them to our hospital block. Each Polish prisoner‑doctor employed in the outpatients’ room had a ‘guardian angel’—a German woman, usually a green triangle [a camp badge worn by convicted criminals] supposed to keep an eye on her to prevent her from helping our women. You needed to be very clever and determined to overcome this barrier. The last group consisted of hundreds of children; their numbers rose after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising. Since they were not used to living in concentration camps, hardship and poor food, a lot of them fell sick.

“The children in the hospital had slightly better conditions but no fresh air. ‘I wrapped their little heads with paper bandages,’ Kościuszkowa wrote, ‘I had no caps for them. I diagnosed otitis and let them stay outside the barrack. They were very happy to be out of doors, while I felt I had done the right thing.’

“‘The infamous Nazi criminal and camp physician Mengele, who performed deadly human experiments on prisoners, including children, was very much against our activities. He was exceptionally mean to us, but we were very clever. I think that when forced to tell lies, you must do it wisely. Mengele was suspicious about patients with a high temperature, thinking that the fever had been artificially evoked: “it’s all a swindle” [alles Schwindel] was his favourite saying. He never actually acted as a physician but as a military policeman. So we recorded slight fever conditions (37.1–37.3 degrees Celsius) to avoid his suspicion, and he fell for it. He was obsessed with ESR tests, and had them done on patients once a fortnight. High results were common in the camp, but there were women whose ESR was low. Mengele permitted those women who had a high ESR to stay in the hospital block; a high result even protected them from being transported somewhere else. So we made exact ESR tests, but in the records I put down readings two or three times higher, depending on the need.’

“‘Mengele was apprehensive of rashes of any kind at all. So we tore paper bandages into small pieces and stuck them at irregular intervals on the patient’s skin. After two days, an awful rash appeared on the skin, which was our new weapon.’

“‘And so we continued fighting for our patients, trying to keep them in the hospital block for as long as possible, getting them an “easy job” or preventing their deportation.i. We knew that we could not keep patients too long in the hospital, so as not to risk their lives and ours. We could not let the SS‑doctor discharge patients. Then there was Lagerältester Ena [Weiss]. She was even worse than the SS‑doctor. She said she was a doctor although she was just a third‑year student of medicine. She gave us a really bad time! . . .’

“‘I had other challenging emotions when I heard that four little girls who had been miraculously saved had been separated from their mothers, put in the quarantine room and were to be sent somewhere. Oh, what weeping and lamenting there was! Yet it happened that I was sent to examine those little girls. Were they healthy? Could they be sent to Germany? With a clear conscience, I diagnosed them with whooping cough, and so they could return to their mothers.’”

A lot has been written about Dr Kościuszkowa’s conduct to the children and mothers in the camp, in foreign publications as well. In his book Menschen in Auschwitz [English translation: People in Auschwitz. Transl. Henry Friedlander. University of North Carolina Press: 2003] Hermann Langbein quotes her interesting remarks concerning the tragic situation of children (pp. 268–270), the abortions done on women brought to Birkenau, the abduction of Vitebsk and Dnepropetrovsk children from the mothers’ block (they were sent to Germany to be brought up as Germans, p. 270), the dreadful sanitary conditions, the congestion, hunger and other hardships suffered by the Birkenau children transported from Warsaw during the 1944 Uprising.

Dr Kościuszkowa is remembered as a good person. Her fellow‑inmates in Birkenau included Dr Alina Przerwa‑Tetmajer, Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska, Dr Irena Białówna, and Dr Stefania Perzanowska, and Zofia Krasińska (married name Leśniak). Krasińska, a nurse who worked with them in the hospital, wrote the following in the year Kościuszkowa died:

“I can summarise her conduct very briefly. [Kościuszkowa] was a person characterised by a very high level of morality; she helped others always and in every situation. She was cheerful all the time, smiling, calm and really helpful—that’s how I remember her. I was involved in the resistance network in the camp, and I brought her many secret messages and medicine for the sick; unfortunately, I do not know whether she was formally a member of the resistance movement and had taken the oath.”

In one of Dr Białówna’s notes we read the following about her fellow‑inmate:

“Dr Kościuszkowa developed all her medical and social skills, and was able to arrive at an accurate judgement of the value of a thing and the needs of every person she encountered, [doing all her best—S.K.] to help fellow‑inmates. After her strenuous daily work, she managed to help sick women in the camp [in Birkenau, not in the hospital—S.K.], those who for different reasons could not, or did not want to stay in the hospital. She was particularly caring for the children in the camp, often giving them food from the parcels she got. When they hugged her, she jokingly said that her pathological obesity had been aptly used at last. . . . I remember her coming to our block to have her lunch; she also used to sit with us in our little room in the evening when she wasn’t visiting patients in the camp. She always passed on heartening news to all whom she met on her way. She never talked about her personal matters at times of stress. She only mentioned her husband and son. In the late autumn of 1944 she was unexpectedly moved to another camp. After the War she told me that she had been sent to Dresden where she stayed in a camp till the end of the War. On her way home, she had to tackle part of the distance on foot.”

Dr Kościuszkowa left Auschwitz in the evacuation transport on 26 November 1944, for the sub‑camps of Flossenbürg: Neu Relau, Dresden, Zatschke and Pirna. Her photo from that camp has not been preserved.

The unpublished typescript of Janina Komenda’s camp memoirs mentions this period of Dr Kościuszkowa’s life:

“In November two Russian prisoner‑doctors, Zhenya Nochnikova from Krasnodar and Olga (I don’t remember her surname) from Saratov or Samara (present‑day Kuybyshev), were deported from our camp within an hour of each other; then Dr Elle Lingens from Vienna, an Austrian physician who was very cultured and supportive, was also transported to an unknown destination. But we were most grieved by the departure of Dr Kościuszkowa, who later managed to return to Kraków after having been kept in various horrible places, including Dresden, which had been heavily bombed.”

Her return home was a time of trouble, walking on foot, and travelling on a supply train or a coal wagon. It ended Dr Kościuszkowa’s most dramatic experience, which evokes the question how she could have endured it all. Here let me quote Alina Przerwa‑Tetmajer:

“Janka had a husband and son both of whom loved her very much. Thinking of them and having a very strong will made it possible for this woman, who had been accustomed to a comfortable life, had never done a blue‑collar job nor practised any sport, to survive the camp and its evacuation, and to endure the extremely hard working conditions in a Leipzig factory which was being bombed nearly every day. She managed to endure the long hours of roll call and had enough strength to come to the children’s block every day; she had to trudge through the mud and pass under the barbed wire, risking the worst repressions; she was seriously ill several times. Finally she crossed virtually the whole of Germany on foot, returned to her beloved city and was reunited with her family, which she had always dreamt of, and returned to her old surgery.”

Wanda Zakrzewska’s article has the following reference to Dr Kościuszkowa’s words:

“We have heard so much about the appalling conditions, the squalor, harassment and constant threat of death that I don’t want to talk about it today. I remember that after having arrived at the camp every morning and every night I used to say to myself, ‘O God, thank you for keeping my dearest ones ignorant of how bad it is here.’ I reassured them in my letters, writing that I was healthy and fine. I have survived, and not just me but hundreds of my fellow‑inmates. Why? Only thanks to the goodness and generosity of my fellow‑prisoners. This is what I would like to talk about today, to tell you what great good human kindness can do with no material resources, just lots of good will . . . I would like to tell you briefly what that mutual assistance was like in the camp. It was like a chain of goodness: Pass it on! Right from my first day in the camp I experienced such goodness that I felt obliged to help fellow‑prisoners as much I could, even if there was not much I could do.”

After her return to Kraków on 19 May 1945, Dr Kościuszkowa started dispensing medical care to survivors and their children, as well as the young people who had survived the Nazi German prisons and concentration camps. She became involved in the Polish Association of Former Political Prisoners of Nazi Prisons and Concentration Camps, and when it was closed down she joined ZBoWiD (the Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy). For a time she was one of the Society’s executive officers; she was a member of its Chief Council. Her home and surgery at Number 11 on Krowoderska in Kraków were always open to those in need, especially children.

Dr Przerwa‑Tetmajer writes that Dr Kościuszkowa

“[E]nthusiastically set to work as a paediatrician. What with the post‑war shortage of physicians, she had to do her best to help hundreds of children. One of her duties was to run a small children’s home, which she did very efficiently, treating all the children in her care as if they were her own. Thanks to her efforts, many of them were adopted by good families and never experienced the bitterness of orphanhood. She was pleased whenever she managed to train a new nurse. She appreciated every piece of furniture or flowerpot she managed to get for that home. She used her authority to provide the very best for children. She went to obtain food supplies, underwear and medicine. Her presence guaranteed dedicated work and kept human relations at the best level. Her optimistic outlook made us optimistic and confident in goodness. Janeczka was always helping someone, bringing out the best in them. She was constantly making new friends and winning patients’ gratitude.”

She was always mindful of her prison and camp experiences and observations. She did not distance herself off from them and wanted to make a record about the truth about the camp, especially about the children’s and her fellow‑inmates’ misery. She published four articles in the 1961 and 1972 issues of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Furthermore, she delivered many lectures and addresses on these topics. She enjoyed the company of survivors and liked to entertain them in her house. She wrote obituaries for some of her former fellow‑inmates (e.g. Ernestyna Michalikowa). She attended several ZBoWiD conventions and events held by similar organisations during which she delivered a speech. She served as a witness in the trials of SS criminals who had committed murders in the Nazi German concentration camps.

After the War she testified in the trial of Rudolf Höss, the commander of Auschwitz‑Birkenau, and in the trial of 40 members of the camp’s staff before the Supreme National Tribunal of Poland. In their book Zbrodniarze hitlerowscy przed Najwyższym Trybunałem Narodowym [Nazi criminals before the Supreme National Tribunal], Janusz Gumkowski and Tadeusz Kułakowski quote her testimony on the dreadful sanitary conditions in Birkenau, the filth and slippery mud in the barracks, the congestion, starvation rations, as well as the emaciation of the prisoners and their harassment by SS‑men.

Shortly after her retirement Dr Kościuszkowa fell seriously ill. In one of her last conversations with Dr Alina Przerwa‑Tetmajer, she said, “I really miss caring for children.” Indeed, Dr Kościuszkowa offered medical care to several generations of children. As reported by Wanda Zakrzewska, Dr Kościuszkowa dedicated many years of her life to working in a home for mothers and children on aleja Pod Kopcem in Kraków, as well as in the nursery on ulica Żuławskiego.

Almost until the end of her life Dr Kościuszkowa continued to treat sick children in her surgery at Number 11 on Krowoderska. She did not talk about her own ailments even though she was suffering herself; on the contrary, she hid or masked her problems, always trying to be busy and working. Her face lit up with a smile whenever she entertained guests; in their opinion she was a perfect hostess. She died on 19 February 1974 after a short illness, and was buried in the family tomb at the Rakowicki Cemetery in Kraków.

Translated from the original article: Kłodziński, S. Dr Janina Kościuszkowa. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1983.

Notes:

a. As for 1983, when the article was first published.

b. Rada Główna Opiekuńcza—the only Polish charity organisation the Germans recognised and tolerated.

c. “Janka” or “Janeczka” are Polish diminutive forms of the name “Janina”, expressing the affectionate attitude of the speakers towards dr Kościuszkowa.

d. Kedyw—the Polish Home Army’s deception, sabotage, and propaganda unit.

e. Stanisław Marusarz, a Polish Olympic ski‑jumper who escaped from the Montelupich jail by jumping from a first‑floor window.

f. Reichssicherheits‑hauptamt, the Reich Main Security Office.

g. Translated from the Polish version in this article by Maria Kantor.

h. Nowadays all the original issues of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim are available here.

i. Viz. the abduction of “Aryan‑looking” children to Germany.

References

This article on Dr Janina Kościuszkowa is based on the following sources:

I. Documents

1. Kościuszkowa, J. Questionnaire for the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum (copy of 18 May 1982).

2. Kościuszkowa, J. Garść luźnych wspomnień z Więzienia Montelupich w Krakowie, 1942/43 (10½‑page typescript memoir of the Montelupich prison, unpaginated, spaced at 1.5 line intervals, undated; in S. Kłodziński’s archive).

3. Resistance movement records, Vol. VII, p. 485 (unpublished texts, preserved in the archive of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum).

4. a) Letter from the Auschwitz State Museum to S. Kłodziński, dated 5 July 1975, 1. IV-8520-271/5706/75;

4. b) Letter from the Auschwitz State Museum to S. Kłodziński, dated 18 May 1982, 1. IV-8520-81/1346/82, giving the basic data on J. Kościuszkowa’s period of imprisonment in Auschwitz‑Birkenau (from the Camp Letters Collection, sign. no. D‑AuI, and the Documents Collection, Vol. 127 “Questionnaires”) and the information that her camp photo has not been preserved.

II. Statements and letters (all the letters are addressed to Stanisław Kłodziński, unless otherwise stated)

1. Białówna, L. 1. a) on Dr Janina Kościuszkowa (1.5 pages, spaced at 1.5 line intervals, undated, compiled at the request of S. Kłodziński);

1. b) on Dr Janina Kościuszkowa (2 pages, spaced at 1.5 line intervals, undated (1975), containing recollections related to Dr Kościuszkowa, compiled at the request of S. Kłodziński).

2. Bormannowa, L .2. a) letter of 17 September 1978;

2. b) Bormannowa’s statement of 19 April 1971 (4½ pages, spaced at 1.5 line intervals, compiled at the request of S. Kłodziński).

3. Burghartowa, Z. Letters of 19 May and 4 June 1982.

4. Jamróz, S. Moje wspomnienie o dr Janinie Kościuszkowej [My memories of Dr Janina Kościuszkowa] (May 1982; 4‑page typescript compiled at the request of S. Kłodziński).

5. Kaleta‑Kiwała, J. Letter and statement of 3 May 1982, compiled at the request of S. Kłodziński.

6. Kłodziński, S. 6. a) unpublished biography of Aleksander Bugajski (typescript);

6. b) copy of a registered letter of 4 March 1980, to Dr J. Kościuszkowa’s son Dr Wojciech Kościuszko, asking for access to his mother’s personal documents for the biography (there was no reply; although I did my best I did not manage to access these resources).

7. Komenda, J. Wspomnienia z obozu Auschwitz II – Birkenau [Recollections from Auschwitz II camp] (typescript), pp. 104 and 145.

8. Leśniak, Z. Letter of June 1974 (no day date).

9. Lingens, E. Letter of 2 September 1980.

10. Przerwa‑Tetmajer, A. Wspomnienie o dr med. Janinie Kościuszkowej [Recollecting Janina Kościuszkowa, MD] (incomplete, two pages of standard typescript, dated 1 July 1977, compiled at the request of S. Kłodziński).

11. Sikorski, J. Letter of 28 May 1980.

III. Publications

1. Bratko, J. Z Pomorskiej na Kujawską droga była niedaleka. Gazeta Krakowska. 1982; 51: 3–4. So far no one has written about this event: in 1943 ago SS‑Obersturmführer Kurt Heinemeyer walked from the Pomorska to the Kujawska in Kraków to arrest the first Communists active in Kraków under German occupation.

2. Czech, D. Kalendarz wydarzeń obozowych. Zeszyty Oświęcimskie. 1960: 78–79 (published by the Auschwitz State Museum); English edition: Czech, D. Auschwitz Chronicle 1939–1945. New York: Henry Holt, 1990.

3. Garliński, J. Oświęcim walczący. London: Odnowa; 1974: 122, 126 and 281.

4. Gumkowski, J., and Kułakowski, T. Zbrodniarze hitlerowscy przed Nawyższym Trybunałem Narodowym. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Prawnicze; 1961: 110 and 125–126.

5. Jamrozik, T. et al. (eds.) (2nd edition). Spis fachowych pracowników służby zdrowia. Warszawa: Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich; 1964: 163.

6. Kłodziński, S. Krakowski “Patronat” więzienny. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1972: 168–176.

7. Kościuszkowa, J. Dr Stefania Kościuszkowa. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1961: 78.

8. Kościuszkowa, J. Dr Ernestyna Michalikowa. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1961: 80.

9. Kościuszkowa, J. Losy dzieci w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1961: 60–61.

10. Kościuszkowa, J. Przez rok w więzieniu Montelupich. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1972: 191–196.

11. Kurkiewiczowa, W. Za murami Monte. Wspomnienia z więzienia kobiecego Montelupich‑Helclów 1941–1942. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie; 1968: 83 and 171.

12. Langbein, H. Menschen in Auschwitz. Wien: Europaverlag AG; 1972: 268–270 and 273. English edition: Langbein, H. People in Auschwitz. Transl. Henry Friedlander. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press; 2003.

13. Madeyski, Z. Wspomnienia więźnia Montelupich. Zygmunt Klemensiewicz. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1982: 152–157.

14. Wroński, T. Kronika okupowanego Krakowa. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie; 1974: 188, item 1112.

15. Zakrzewska, W. Więzień nr 36319. Pamięci dr med. Janiny Kościuszkowej. WTK – Tygodnik Katolików. 1974; 21: 6–7.