Author

Stefania Perzanowska, MD, 1896–1974, participant of the Polish WW2 anti-Nazi resistance movement, survivor of Majdanek (camp no. 235), Auschwitz-Birkenau (no. 77368), and Ravensbrück (no. 107185), prisoner doctor and main organiser of the women’s camp hospital at the Majdanek concentration camp.

Although the purpose of all concentration camps was identical, and so was their internal structure, actually they differed a great deal. The differences stemmed from the specific features of each camp that arose due to particular situations and circumstances, and ultimately accounted for the local conditions.

Such was the case with the women’s camp at Majdanek (KL Lublin). It was established quite late, in January 1943.1,2 The first transports were of Polish political prisoners only. The Germans had no choice but to appoint them to various supervisory positions, especially as the camp had to take in crowds of new arrivals within a short time. That was a decisive factor for this place of detention.

The Lagerälteste was the timeserver Żenia Piekarska, who had been previously imprisoned in the Pawiak jail in Warsaw. As she claimed to be a Reichsdeutsche, at Majdanek she became the commandant’s confidante and rivalled her in beating and harassing other women prisoners—yet she did not manage to alter the relations already established in the camp.3 Though Piekarska was a leader of her pack of beasts of prey, they were a small and isolated group, because the vast majority of other functionary women prisoners were honest and friendly Poles, even showing concern for those whom they were supposed to supervise. Their attitude, which went hand in hand with that of most of the other Polish women, determined the ethically unambiguous atmosphere in the women’s section of the camp.4

These characteristics of Majdanek Frauenlager (women’s camp), briefly described above, to a large extent shaped the hospital that was being established and the work of all the medical staff.

By a strange and rare coincidence, for a few months I was the only woman doctor in the camp. Every day prisoners came to me with their problems, but I could neither examine nor treat them. Whenever I requested the commandant to give me the chance to treat them, she responded by yelling and swearing. After a few days a German male doctor turned up, and insulted me, calling me an “idiot,” because I dared to say one of the prisoners probably had typhus. Two days later, when the sick woman had developed a typhus rash, he had to grant my request: one barrack was to be converted into a hospital and I was to plan and oversee it. Therefore I had to find my staff, so I visited each of the barracks, inquiring if there were any prisoners who had the qualifications to join my future team.

I found some volunteers among the women from the Warsaw transport: Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko, a third-year medical student in the Polish underground educational system; Halina Cetnarowicz, a first-year medical student; Irena Todleben, a chemist and bacteriologist; and four certified nurses: Zofia Orlicka, Wanda Orłoś, Wanda Ossowska, and Maria Żurowska.5 A few of my staff had arrived in the Radom transport:6 Jadwiga Łuczak, a dentist; Józefa Wdowska, a pharmacist; and Stefania Sawicka from Skarżysko, who was trained as a nurse on the job. Also, about twenty more women volunteered to work in the hospital, though they had no formal training.

All of them formed my first staff. We discussed our work plan and our goals. The certified nurses and some of the unskilled prisoners were to be employed in the hospital; the others were to build up a sanitary unit to keep an eye on prisoners’ hygiene and fight the lice infestation.7 We naively hoped this unit could eliminate the harmful insects and keep the camp clean. Yet the realities prevailed over our plans and objectives: the camp had no sanitary infrastructure and no water supply, as the well was icebound, and the prisoners’ blankets were teeming with lice. Nevertheless, the sanitary unit worked hard and persistently, which produced the best results obtainable.

Initially, the camp’s German officials did not interfere with how our tasks were divided or who was employed in the hospital, which proved beneficial. The hospital that was being established was of no concern to them: all we got was an empty, unfurnished barrack of eight rooms. Left to our own devices, we either wangled or made three-tier bunks and mattresses, which we filled with wood shavings. Prisoners from other barracks gave us some blankets, bowls, spoons, and electric light bulbs. The hospital’s assets also included the first official assignment of equipment: a stethoscope, a thermometer, and a small batch of basic medicines.

When the first room was ready, it took in the first group of patients with typhus (by that time there were nearly twenty of them). Having converted the entire barrack, we could put up all the sick prisoners, and so in early February 1943 the hospital in women’s section V started to operate.

After ten days, at last the camp’s sanitary inspectors bothered to show some interest in the infirmary, and we received some thermometers, bed pans, syringes, an autoclave, and a second, very small batch of medicines. Afterwards, a few chairs, stools, and bowls arrived.

The women’s section had more and more prisoners because the transports, especially of Russians and Jews, were large and frequent.8 Consequently, the number of our inpatients grew and more hospital barracks had to be adapted. The typhus epidemic spread.

***

It has often occurred to me that “hospital” was perhaps too grand a word to denote the incredibly primitive place where sick prisoners were accommodated at Majdanek. In the camp jargon, it was referred to as the rewir (from the German word Revier). I did not like using German when it was not absolutely necessary, so I did not like the word rewir, either. This is why we called the establishment a “hospital,” although it did not meet the most rudimentary standards.

The buildings were simple wooden cowsheds and the beds were three-tier bunks. Every patient had a mattress and a blanket, but there were no sheets or pillows. It was highly inconvenient to have an unconscious typhus patient in a top bunk, but often there was no other way. There was no running water in the barracks, so it had to be fetched from the well. When the well froze up, we had to melt ice or snow. Bed pans had to be emptied into a pit latrine outside the building. So, working in such primitive conditions, which are not what you would normally expect in a hospital, we strove hard to be at least as professional and conscientious as the staff of a hospital worthy of the name.

This is why I needed to recruit good colleagues, and fortunately managed to find them. The work of experienced and dedicated nurses was truly invaluable, especially as they took care of feverish, often unconscious typhus cases. My unskilled staff showed as much commitment, being trained on the job by the professionals. We actually ran a kind of nursing school, though we had no lectures or training dummies, but instead, from the start, responsible work with people who were severely ill. When I had a spare moment, usually in the evening, I gave my staff short talks on anatomy and physiology, asepsis, symptoms of the most common illnesses, and the course and importance of some procedures. Using one another as a model, the girls learned how to take a patient’s pulse or even how to give injections. Some of them were not formally adults yet, because whenever I could, I offered hospital jobs to those teenage convalescents who seemed eager to stay on; I wanted to protect them from hard physical labour, beating and abuse by SS guards after a period of illness. One of those girls, her parents’ only child, was just fourteen when she saw the Germans shoot her father against the wall of their family home, which was in Warsaw. Afterwards, she was deported to the camp. Out of this group of my teenage trainees, four are now doctors and one has graduated from a nursing school in Warsaw.

Each hospital barrack had an appropriate number of its own nursing staff, depending on the number of patients in it. Their work was supervised by a ward nurse (whose function was comparable to the Blockälteste in the living barracks). The cleaners were treated as orderlies in a regular hospital. The hospital office registered the patients and kept their medical records.

All the nurses worked eight-hour day and night shifts according to a schedule. Those on duty took the patients’ pulse and temperature three times a day. The information was put down on the temperature charts we had drawn on our own and hung on each bunk. The nurses also took down the doctor’s orders during daily rounds. They washed the bedridden patients, combed their hair, and fed them. They washed the soiled shirts, as there was only one for each patient, and left them to dry on the stove. They changed the fouled mattresses, gave the patients bedpans, and went out to empty them. All these tasks had to be performed for the patients occupying three-tier bunks, so they involved quite a lot of climbing up and coming down. It must be remembered there was no water supply in the barracks. The nurses, warm-hearted and dutiful, also performed many other medical procedures.

This period of training was difficult but fruitful. During the year following the establishment of the women’s camp and hospital, there were often as many as ten barracks full of sick people, while we had about one hundred nurses. But later their work was much more efficient, because they had become experienced hospital staff, loyal colleagues, good friends, and kind carers. The hospital operated for about a year and a half and in that time there was only one occasion when I had to intervene to stop an argument between two nurses. They had to work in different barracks to avoid misunderstandings. It was possible to achieve such harmony, because I was not pressured while I was organising the hospital and recruiting the employees, so I believed I was choosing the best candidates.

However, the German functionaries did not approve of the “excessive” number of staff and of the fact that the nurses worked eight- and not twelve-hour shifts, like the rest of the prisoners. Lying to the SS men and manipulating the schedule, we managed to keep working in the usual way for as long as the hospital was in operation.

At the beginning some nurses were quite reserved in their attitude towards me. We had not known one another before, because I came from Radom, while most of them were from Warsaw. At work, I require a lot from my subordinates, I tend to be bossy while giving my decisions, and do not show my preferences and feelings until I know my colleagues well. But once that had happened, my collaborators and I understood one another readily, made friends, and remained really close. We communicated instantly, sometimes without words. Entering a barrack, I could read the nurses’ faces and immediately knew whether the situation was fine or serious.

***

While the number of the nursing staff was fairly adequate, the number of doctors was highly unsatisfactory in the entire history of the hospital. In the early stages, actually, I was the only doctor. My assistant was Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko, a third-year medical student in the Polish underground educational system.9 She was nice, clever, and hardworking, and showed some surgical skill, but definitely her knowledge of medicine was not enough to let her work unsupervised. Nevertheless, she was a great help, especially during minor surgeries and wound-dressing, and we did the daily rounds together. After a few months Hanna was released from the camp thanks to the determined efforts of her family.

Soon afterwards, in early May 1943, a young doctor arrived from Lublin jail. Her name was Aglajda Brudkowska. We worked together for as long as the hospital was open, i.e. until April 1944. Aglajda, nicknamed Ada, was the exact opposite of Hanna. Both of them were young, but Hanna, dark-haired and ruddy-faced, was bubbling over with energy, although she had been imprisoned in the Pawiak jail and then in the camp. She was kind-hearted and glib, impulsive and lively. Hanna talked a lot, so I knew all about her baby daughter, mother, and husband, as well as her longings and worries. Ada, on the other hand, was a blue-eyed blonde, pale, thin, timid, and taciturn. She hardly ever expressed her feelings, and upon arrival in the camp looked utterly exhausted, both physically and mentally. She must have had serious secondary anaemia, as she was barely able to walk and suffered from frequent migraines. Both Hanna and Ada were honest, sincere, and hardworking, but Ada had to put much more effort into her duties, which was the more endearing and praiseworthy. Hanna was interned in the camp for just a few months, while Dr Brudkowska worked there for over two years, growing more and more asthenic, emaciated, and grey in the face. Both of them survived and are still working as doctors: Hanna in Warsaw and Ada in Puławy.

Shortly before Hanna was released and Ada arrived, the German nurse Reinerzt10 brought a young Jewish doctor, Maria Marder,11 but the orders were that she was allowed to work only as a sanitary inspector in the barracks and washroom, because before long she was to join one of the “transports.”12 Maria, whom we called Niusia, lived with us, but at the beginning she did not talk to us at all and moved about as if she were in a trance. Her face, unlike the faces of most Jewish women, did not express fear, only dejected bewilderment. One night after she had been with us for a few days, I heard her crying, so I went up to hug and stroke her. Then she started talking. She had been taken to Majdanek from Treblinka, where she saw her mother, also a doctor, and her little son being taken to a gas chamber to be killed. She wanted to join them and die too, but the Germans forcibly parted them and sent her to another camp.

Niusia was not “put on a transport.” She became our colleague and friend, and after a while recovered her healthy looks and will to live. She was polite, kind, and supportive. After a bad spell of typhus, just when she came to me and we decided she would go back to work the next day, because she was feeling fine—she was killed on 3 November 1943, with all the other Jews.

***

After the Uprising in the Warsaw Jewish Ghetto had been crushed on 16 May 1943 and the whole Jewish district razed to the ground, Majdanek received a large transport of Jews and the hospital found about twenty new doctors and nurses: the staff of the Jewish Hospital in the Warsaw district of Czyste.13 SS doctor Blancke14 allowed all those women prisoners to work in different barracks, but within a few days the majority of them went down with typhus: they must have arrived in the camp during the incubation period. They recovered, but on 3 November, which the Germans called Erntefest (“harvest festival”), the day when all the Jewish internees were murdered, they were still in hospital as convalescents.

In the afternoon of that nightmarish day, all the Jewish patients and medical staff were ordered to board trucks (to take them to the place of execution). I told the Jewish doctors and nurses, also the convalescing ones, to put on their white coats and to wear their Red Cross armbands, vainly hoping that the emblems of their profession might change their fate. On that horrid day their uniformed white column left the camp in rows of five. 18 thousand Jewish prisoners were killed.

By sheer luck, Dr Alina Brewda15 avoided the massacre. Before the war, she had been head of the maternity ward in the Jewish Hospital in Warsaw. The Germans kept a meticulous record of the doctors in all their camps, so when the Jewish ghetto transport arrived at Majdanek, they registered both the number of the doctors and their specialities. Dr Brewda became one of the hospital staff and, due to her speciality, was in charge of minor surgeries and obstetrics, which was a relief to me, as I did not like delivering babies. She did not serve in that capacity for long, because the commandant received a letter from Berlin, saying that Dr Alina Brewda, a surgeon and gynaecologist, was to be immediately transferred to Auschwitz. Alina did not want to go, as no one liked to venture into the unknown, and Auschwitz was not considered a better place than Majdanek. We petitioned the SS doctors, but without success. Dr Brewda left the camp sad and confused. Apparently, as the orders had said, she was escorted by the commandant Else Ehrich.16 Thanks to that journey, Dr Brewda’s life was saved. When we met again in April 1944 at Auschwitz, she was unable to grasp the fact that all her colleagues from the Warsaw Jewish Hospital had been killed. Alina survived, and is living and working in London.

Helped by various people and institutions, I tried to make a full list of the Jewish medical staff who were murdered at Majdanek. However, I cannot be sure it is complete, and my sources were not sure, either. We tend to remember heinous deeds, but some names are forgotten after a while. Those that I managed to save from oblivion are given in alphabetical order. The doctors were: Braule-Hallerowa,17 Folmanowa, Irena Gradzińska,18 Maria Marder, Najster, Najburzanka,19 Przeworska,20 Irena Rubin, Orlis,21 and Wdowińska.22 The nurses were: Altszul,23 Rysia Bielicka, Dora Cukier, Dziubas, Fryd,24 Frydman, Gryll, Helena Gallowa,25 Ickowicz, Izerlis,26 Nina Najdycz, Nebel,27 Odes,28 Podlipska, and Próżańska.

***

In late 1943 the overcrowded women’s section at Majdanek, where 10 thousand prisoners were interned, had to take in more transports. Usually the deportees were Russian women, scrawny, emaciated peasants, totally helpless and vulnerable.29 They vegetated in abject misery: imprisoned so far away from their home villages, their received no food parcels, and being so defenceless, they were constantly beaten up and harassed by the German functionaries.

Lastly, just before the hospital was evacuated, we received ten helpers, young Russian doctors, who worked with us for just a few days and then we were all transferred to Auschwitz.

Once a small Russian transport arrived; the deportees looked different. They turned out to be women guerrilla fighters, treated as POWs. There were four doctors among them who volunteered to work in the hospital, where they stayed for a few months before they were sent to Ravensbrück.30 The Russian doctors were diligent and cooperative, but found it hard to communicate, as they spoke only their mother tongue. I can remember two names: Lidia Simbirtseva and Nadia Pavlenko.

Such provisionally employed staff were of immense help, but because they stayed with us for a short time, we were unable to divide our tasks differently in the long run. For a few months there were no other doctors but Ada Brudkowska and myself. As we could not get any other physician to support us, the number of nurses we had exceeded the Konzentrationslager standards, and made things easier.

We were permanently overburdened with work. In mid-1943, during the peak of a typhus epidemic, the hospital was housed in six barracks and had 500–800 inpatients. Our shift began at dawn and ended late at night. In the morning we worked in the dispensary, but after the evening roll call we had to examine those women who fell ill during the day, put dressings on leg wounds, caused by wearing clogs, or on injured heads or shoulders of those prisoners who had been beaten. The morning examinations and admissions in the dispensary were followed by our daily rounds in the barracks. The nurses described the condition of the sick and took down our current orders. With crowds of inpatients, we had to continue until the late hours, and we also worked Sundays and holidays.

We considered it our priority to keep those daily rounds as similar to regular hospital visits as possible and to rouse the women from the stupor and misery of their existence in the camp: we wanted to tap their survival instinct. The conditions were incredibly primitive, the quantity of medications far from adequate, and the terror in the camp appalling, so we wanted to have a good atmosphere in the hospital and to show we were experienced professionals, in order to make the patients believe it was possible to tough it out and recover. Of course that conviction, to a large extent, had to stand in for proper treatment.

***

It was impossible to forget we were confined in a concentration camp. Every day could offer plenty of awful surprises, and it was the Germans’ ambition to torment even the hospital staff and patients.

Whenever we had a sudden inspection by the commandant Else Ehrich, which happened very often, she would regularly come down on us and on almost every occasion a member of the staff was beaten up. She was always discovering that we had transgressed the camp regulations, e.g. by boiling a bowl of water for the thirsty patient, that a nurse had a stooping posture while she should be standing at attention, that the stove was too hot, and a blanket not smooth enough on a bunk. Such “offences” definitely deserved to be punished with physical and verbal violence, and the bowl of boiling water had to be furiously kicked off the stove.

Such inspections, luckily, did not take place daily, and they tended to be brief. Actually, the most awful nuisance were the SS orderlies, who were officially the hospital’s employees, so they lazed around all day long. In practice, their only occupation was harassing the patients and disturbing the staff’s work. When they got into a frenzy of “tidying up” or “reorganising” the hospital, they would trail their fingers on the ceilings to show they were dusty; empty the shelves and cabinets in the dispensary, throwing the equipment on the floor, because it “needed rearranging;” tear up the “wrongly filled in” medical records; force us to discharge “malingering” patients or to transfer them to a different barrack. Their chicanery was getting ever more malicious and absurd, while their inventiveness was unfailing.

Two unsurpassed harassers were Reinertz and Mußfeldt.31 The latter was head of the crematorium and a hard drinker. When intoxicated, he would take out his revolver and keep shooting at the floor or at the stool legs or really at anything. Once, drunk, he dragged me to the crematorium, promising to finish me off for sabotage and disobedience. Yet an hour earlier, the deadly facility had broken down and was closed.

The third SS orderly, named Konietzny,32 took it out on Jewish prisoners during selections in the washroom. He was even crueller than his workfellows, and after a selection all of them would return to the hospital with a rich loot of watches, jewellery, and gold – the victims’ possessions. Reinertz’s favourite procedure was abscess incision, and the prisoners had plenty of abscesses because of lice bites and scabies. Reinertz operated on the patients with his unwashed hands, and he liked to wipe a sterilized scalpel against his dirty trousers. Fortunately, the frightful trio did not stay with us for as long as the hospital functioned; they were replaced by Havenith, a male nurse who never got drunk and never started rows, so we were able to work in relative peace.

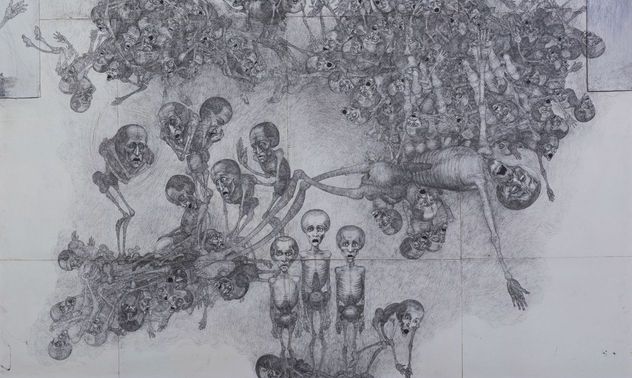

Apotheosis of Death. Marian Kołodziej. Click to enlarge.

The hospital was supervised by the German doctors. Their head was Bodmann33 and his deputy was Blancke,34 who had an assistant called Rindfleisch.35, 36 They showed no interest in the treatment as such, perhaps with the exception of the young assistant. Such a situation was not unique: generally German doctors in concentration camps would not degrade themselves with the chores of medical care, but what really inspired them were selections, tantamount to pronouncing death sentences. So the fact that at Majdanek the German doctors did not interfere with the business of the hospital was a true blessing, e.g. they did not control the admissions and discharges, which proved beneficial both to the staff and the patients.

It is hard to grasp why it was the doctors in Nazi German concentration camps who had to act like mass murderers. Why was the grim task not assigned to the rank and file SS executioners? Why would qualified doctors and nurses become involved in such crimes? For they had been trained to realise their job was to save lives, cure and provide medical aid and emotional comfort – not to send anybody to certain death. What is more, German doctors in the camps pursued their bloody occupation without any qualms, but with a vicious grin on their faces – like Blancke, an evil twinkle in the eye—like Mengele,37 or a terribly bored face—like Fischer38 at Ravensbrück. Blancke shot Jewish women when they tried to leave the column marching to the gas chamber. With my own eyes, I saw Mengele first taking out tiny Jewish babies from the prams that were lined up on the Auschwitz ramp and then tossing them into the ditches full of burning bodies. Doctors Gebhard39 and Fischer carried out wide-scale, pseudo-medical experiments on young Polish women in Ravensbrück. I always shrink from calling those criminals “doctors.”

Still, at the Majdanek women’s hospital they did not check who was admitted. What was even more puzzling – and propitious – they never carried out selections of Jewish patients there. The selections took place either in the washroom or outdoors within the perimeter, but not in the hospital. But I know that the hospital in the men’s camp witnessed several selections by the German doctors, not only of Jewish patients, but of any nationality.

“Selection” is an innocent word, and reference books explain it involves an act of finding out and choosing. In the camp, “selection” became heavy with its new lethal meaning. Blancke laughed and the SS orderlies yelled when they pulled out selected women out of the rows of five: they separated those prisoners from their fellows, and sentenced them to death. The next stage was the gas chamber. Blancke liked peeping in through the small window to see his victims in their terminal convulsions. When the “business” was over, the dead bodies were taken to the crematorium, and a coda to the crime was the choking smoke belched up by the chimney.40

***

A typical example of the absurdity of the camps’ operations as well as of their brutal treatment of the prisoners, was the transfer of 800 malaria41 patients from Auschwitz to Majdanek in the spring of 1943. All of them, Jewish women from Greece and just a handful of Poles, had to be admitted immediately and they were a pitiful sight. They kept trembling – both because of the cold climate and their illness. They huddled together in small groups and scanned the neighbourhood with their fearful eyes. Famished and thirsty, they scavenged for any food or drink they could find. But then summer came and the temperature went up, and when our Greek patients were at long last better fed and more adequately treated thanks to the humanitarian aid of the Polish Red Cross and the RGO,42 they changed and improved. They did not shiver any more, but recovered their girlish appearance and prettiness, from time to time ventured a smile, and were not so fearful, but more trusting and open. Precisely when they were rediscovering their humanity, and perhaps their will to survive, they were all killed on that dire day, 3 November 1943.

***

The sanitary inspectors in the camp were never short of surprising ideas. At the height of the typhus epidemic in early June 1943, the hospital received an order from the main office: no more cases of the disease were to be reported. We did not know how to respond, having two barracks full of patients with typhus. The next morning, Mußfeldt appeared in the dispensary. He entered when I was examining a woman who had been brought in from one of the barracks. Seeing her rash, he enquired: “Typhus?” When I confirmed the diagnosis, he ordered the staff to take the woman to an empty storeroom, went in, and locked the door. Several minutes later he left the place and told me to look inside: the poor soul was dead. He had killed her with an IV injection, probably of phenol. Pointing to the body, he kept shouting: “No more typhus cases in the women’s hospital! Understood?” Indeed, I realised the danger to any patient with typhus and the consequences of reporting a case. I instantly figured out that one more spectacle of hypocrisy was to be played in the camp’s macabre theatre.

My staff and I spent the whole night rewriting all the medical records and temperature charts for the patients in both “typhus” barracks. The next morning, those two buildings housed patients with any plausible diagnosis except typhus. It was such an instant and radical way to stop the epidemic! And I was never asked what happened to those cases of typhus that had been reported two days before.

However, one more electrifying surprise was in store for me shortly thereafter. We were informed a board of medical inspectors from Berlin was due to arrive in the camp. A group of six Germans, led by Blancke, turned up, and I had to show them round. In the “typhus” barracks, I recited the catalogue of made up diagnoses, but feared that the ruse would be exposed, because the patients’ appearance was clear evidence of the “unmentionable” disease. Yet the inspectors just hurried through, never stopping to look at any woman. Finally, they just wanted to make sure: “Kein Fleckfieber auf Lager?” (No typhus in the camp?) My reply was quick and dutiful: “Jawohl, kein Fleckfieber.” (No, sir, no typhus at all.) The show was over, and the patients, regardless of their diagnoses, were left in peace to recover.

The reason why we were not permitted to report typhus cases testified, yet again, to the Nazi German partiality to outward show: the Majdanek commandant had received a letter from Berlin in which she was told that all leave for the SS personnel would be cancelled if a typhus epidemic broke out.

***

In July 1943, due to the intricacies of Nazi logic, the camp had to take in several hundred women and children from the regions of Zamość and Biłgoraj.43 We saw three women with little bundles in their arms: babies they had given birth to the previous night, travelling in overcrowded cargo trains. The umbilical cords had to be bitten off and the infants were swaddled in items of their mothers’ clothing. The day following the birth was spent walking from Lublin to Majdanek, which is several kilometres away. We admitted those women, though they were not too eager to stay in hospital. Soon, the postpartum period was over and the babies were fine. After the transport of the Zamość women had arrived, we delivered several of them. As there were no baby clothes, we used paper bandages at first, but the prisoners working in the sewing unit provided us with tiny shirts and nappies. Many of the older children went down with measles or chicken pox, and at the peak of the epidemic the Zamość prisoners were released from the camp.44 Amid our protests, children with a fever and a rash were taken away from the hospital by their mothers, because the most important thing was to leave the godforsaken place as soon as possible, together. Providentially, that summer day was warm and sunny.

In September, following a track of similarly twisted logic, all the women’s camp was moved to section I. There was chaos and plenty of work when the patients were being transferred: we had to clean up the assigned barracks, which were extremely dirty and infested with fleas, and to find our way in the new location. On the face of it, section I was not very different from section V: the same buildings, the same muddy street with a gallows in the middle. However, there was a valuable addition to the camp “infrastructure:” section I had a water supply and sewerage system. At the back of each barrack, there was a washroom with troughs and taps as well as a few primitive toilets: a real luxury in comparison with the unroofed pit latrines in section V.

The hospital was arranged in six barracks. The first one housed a dispensary, an office, pharmacies, two patients’ rooms, and a dental surgery, which, sparing no effort, we had managed to equip still in section V. It was run by Jadwiga Łuczak from Radom, an experienced dentist. Józefa Wdowska, who held a master’s degree in pharmacy and had also been deported from Radom, was head of the pharmacy. Both were patient and careful. We also acquired a quasi-lab, which was run by Irena Todleben, a chemist and bacteriologist. The “lab” occupied the space of a table in barrack IV and included a microscope, the most basic analytical kit, and an electric stove.

Our collaborators were the sanitary unit, who found it so convenient to have access to running water in the barracks. It was now much easier to keep the buildings tidy. As a result, the typhus epidemic started to subside. When it was stopped altogether at the beginning of 1944 and we were looking forward to less work at last, in early February a huge transport of 780 severely ill women arrived from Ravensbrück.45 Although, as veteran prisoners, we had become habituated to the cruelty of the camp, we were absolutely shocked to see them.

All the new arrivals were wafer-thin, and their pale, greyish faces looked like masks whose only expression was that of utter exhaustion. It seemed impossible for those skeleton frames to still be able to stand up, walk, and talk. They had been travelling in cold cargo trains for two and a half days without any food or drink. In Lublin they were tossed onto trucks, like unfeeling logs, one layer upon another. All of them were seriously ill. They told us that the previous week, Ravensbrück had seen a large-scale selection in all the barracks. Because of their bad condition, they were selected to be killed by gassing. But then the crematorium broke down. After two days of waiting, they were sent off to Majdanek.46 This is how we came to know why the faces of those prisoners, condemned to death, had turned into lifeless masks.

Ada Brudkowska and I spent two days from dawn to dusk examining the poor creatures. Then we admitted them to various barracks and they had to be put up even in the recently acquired common washroom. Initially they were unable to understand that they could get some medical aid, that somebody would take care of them, treat them, and help them survive. And we were able to treat and feed them relatively well thanks to the Polish Red Cross and the RGO, as well as several selfless inhabitants of Lublin.47

We had a multitude of different diagnoses. Many patients, especially young Polish and Yugoslav women, had tuberculosis. There were cases of arthritis and spondylitis, which led to bone deformations, of chronic heart failure and, consequently, swollen limbs, of kidney and bladder diseases, of severe diarrhoea, and even seizures due to typhus complications. For instance, we treated a nice elderly Dutch woman who had a spastic seizure after typhus, and a young Belgian girl with extrapulmonary TB of the spine and paresis. The girl had suffered terribly, lying on the floor of the truck and bearing the weight of other bodies on her.

It was difficult to treat such serious, chronic cases and took a lot of time, the more so as the patients were in a stupor or felt constant anxiety for many days. However, gradually, there were fewer oedemas and diarrhoeas, the TB patients improved, and the partial pareses receded. The Belgian Peggy Solemé48 got a special plaster cast cradle. Some of those patients accompanied us in April, when the hospital was evacuated to Auschwitz, while the convalescents were discharged and stayed in the Frauenlager, only to be sent back to Ravensbrück when Majdanek was closed.

***

By February 1944 the Majdanek women’s hospital had as many as ten barracks. It had been functioning for two years and had treated thousands of women. This huge number was connected with the multitude of diseases prevalent in the camp.

At Majdanek, as in all the camps, the most common and also the most severe illness was typhus. We had typhus cases from the very start of our work in the hospital. The incidence waxed and waned, depending on the intensity of infestation with lice.49 There was an epidemic in 1943, lasting all year long, which subsided when the winter came and stopped completely in early 1944. It was a real achievement of the sanitary unit, which systematically eliminated pediculosis.

However, in 1943 typhus was so common a condition that only a handful of prisoners did not catch it. It is considered one of the most serious contagious diseases, because initially patients run a high temperature, become unconscious or hallucinate, and feel anxious; after a while, when their temperature drops, they are very weak. While working in the camp, I noticed there were fewer complications following typhus than after typhoid. The latter was a constant presence too, but the incidence was much lower. Treating either condition, we were mainly concerned about the heart muscle, because we had no particular medicines to treat the disease as such. With convalescents, it was of vital importance to keep them in hospital as long as possible and, with typhoid patients, to follow a special diet.

The second most frequent and most serious health problem in the camp was diarrhoea (Durchfall). Hardly anyone avoided a spell of it, and many prisoners had it repeatedly. The first year of imprisonment was critical. The course depended on your general health. The weaker and more emaciated a woman was, the more severe her diarrhoea. Usually it was persistent, quickly left the sick person dehydrated, and impaired the functioning of the heart. I suppose one of the main causes was the camp food, with little fat or protein, and no vitamins. Also, the prisoners had to eat half-raw and sometimes half-rotten swedes in cold soup. This diarrhoea was not starvation diarrhoea yet – we saw that after we had been confined for longer: it was always accompanied by pronounced oedemas and proved much more difficult to treat. Obviously, in some cases one type of diarrhoea followed the other, or they were comorbid.

The hardest thing to do was to stick to a diet. The Polish Red Cross and the RGO sent us vats of dietary soup twice a week, which was a great help, like food parcels from home. They were a true blessing, as I was to find out later: at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück diarrhoea knackered the sick women out, because they just had to go on without any food for several days.

Scabies was a very common condition, bound to appear in any camp due to infestation with lice, no hygiene, and no sanitary installations. In autumn and winter, when it was too cold for most women to wash, the problem was at its worst. The most frequent complications were furunculosis, large abscesses, or purulent infections of the scratched skin.

At one point there were dozens of cases of erythema nosodum, whose course, however, was rather mild and uncomplicated. Interestingly, all the infected women belonged to the same unit of potato peelers.

TB was another disease prevalent the camps. Usually it affected the lungs, but sometimes also the bones and spine or the skin. Obviously, no X-rays or lab tests were available.

As for contagious diseases, there was a short epidemic of measles and chicken pox among the children from the region of Zamość, and we had about 800 cases of malaria in prisoners who had been deported to Majdanek from Auschwitz. I remember several cases of tonsillitis and one, surprising case of diphtheria. Moreover, there were numerous internal medicine problems, such as chronic cardiovascular failure accompanied by limb swelling and sometimes ascites.

Some unexpected health outcomes were also observed. For instance, women who had had problems with their stomach, liver or bile duct, felt their symptoms subsided. What apparently helped was the fatless food, as well as absence of tea, coffee, or broths in the diet.

Venereal diseases were rare. Even though every concentration camp had a brothel, the group of clients was small and included the SS men, those prisoners who were Reichsdeutsche or Volksdeutsche, or some Kapos for “distinguished service.” At Majdanek, in the spring of 1943, the camp’s chief physician informed me that the Wasserman tests and cervical smears were a must for women who volunteered to work in the Puff. During the morning roll call the commandant announced such an establishment was to be opened and candidates were required to report at the dispensary for tests. The samples were sent to a lab in Lublin, and the results were dispatched to the hospital. To my surprise, dozens volunteered. They kept inquiring when they were going to commence work, but in fact the brothel never started its operations. Wasserman tests were also done monthly for those women who worked in the SS kitchen.

Our major concern were the mentally ill. We had over ten of them and the group always grew after mass executions, beatings, or frequent selections. They had schizophrenia, severe manic depression, and other problems. What was surprising, though, was that neurotic disorders or female hysteria were practically absent.

A common psychophysiological abnormality was amenorrhea. Women stopped having their menstrual periods when in jail, and this condition continued for the rest of their imprisonment in the camp. I knew very many girls and women who never had a period in all those years that they spent behind the wire fence, but started menstruating again just a month after their release. Amenorrhea was often concurrent with many other symptoms, such as persistent migraines, hot flushes, pain in the lower abdomen, and increased irritability.

It was only in the camps that I came across so many cases of vitamin deficiency. The onset occurred after a long period of detention. Only those prisoners who were deported from Russia had already developed vitamin deficiency problems. Also, the Greek internees who had arrived from Auschwitz suffering from malaria, had scurvy of various types and intensity. When we started receiving extra food from the Polish Red Cross and the RGO, for instance brined cabbage, which was one of the requisitioned provisions, their scurvy receded in no time at all. I would never have believed advanced scurvy could be treated so quickly, if I had not seen it with my own eyes. There were also skin and eyesight problems caused by vitamin deficiency. Many symptoms of deteriorating health ultimately turned out to be just consequences of a vitamin-deficient diet.

***

The number of inpatients depended on the overall number of the camp’s prisoners and on whether we were having an epidemic or not. In mid-1943, when the hospital had six barracks, there were 500–700 inpatients on average. After the Ravensbrück transport arrived, that number grew to 1,300 and the sick women had to be put up in ten barracks. And we were evacuated to Auschwitz with about 700 patients. 50

The mortality rate in the women’s hospital, considering the appalling conditions, was not too high, and it tended to change with the incidence of typhus. Talking about the mortality rate, I often think of dead people, because one of the many horrors of the camp was lack of respect for their bodies. Human beings were held in contempt when alive, and even more when dead. The only trace of the women who had been killed in the gas chambers and burnt in the crematorium was the nauseating smoke. The bodies of those who died in the hospital were also taken to the crematorium. Another barbarity was the order to remove gold dental caps from the teeth of the dead. For a while, this procedure had to be performed by a doctor from the men’s camp, and then by the dentist from the women’s hospital, supervised by an SS orderly.

On the other hand, clothing was considered valuable, so the dead bodies had to be stripped naked and only then piled up on the ground behind the barrack. In section I, they were laid in the washroom. Every morning, a team of corpse removers arrived from the men’s camp. Equipped with a wheelbarrow, they took the bodies away, traversing the camp. The wheelbarrow was small and shallow, so the limbs of the dead people dangled over the rim or trailed along the ground. When one of the nurses lost her mother, she and her colleagues wanted to take the dead woman out of the hospital on a stretcher and dressed in her striped camp gear. Blancke and Ehrich bawled them out.

I was haunted by nightmares about the camp for several years after the war. In some of them, I again saw the arms of my dead patients banging against the sides of the wheelbarrow or their legs dragging over the ground.

***

The multiplicity of health problems as well as the number of prisoners who needed medical aid were in stark contrast to what we could offer as treatment, especially in the first month of our imprisonment at Majdanek. No access to medicines was a constant and painful predicament in all camp hospitals and exemplified the perfidiousness and duplicity of all Nazi German regulations. The barracks were full of the sick, while we had practically no pharmaceuticals to administer: that was our reality and our constant worry.

Every week, we were supposed to write an official requisition, also reporting the number of patients, and send it to the main pharmacy in the men’s camp. However, we received next to nothing. A weekly assignment for a few hundred poorly women included just some painkillers and anti-fever pills such as acetylsalicylic acid or sulphonamides, especially the popular Prontosil; activated charcoal and bolus alba to fight diarrhoea; and for heart problems, valerian drops, Cardiamid, caffeine, and camphor, three vials of each. We were also supplied with about ten paper bandages, a packet of gauze or cellulose wadding, and some ointment.

Obviously such supplies were far from the minimum needed, and the situation seemed difficult, not to say hopeless. Fortunately, the sick prisoners were helped out by the magnanimous inhabitants of the Lublin region. Although the camp was an isolated place, they had some information about what was going on behind the barbed wire fence.51 So those honest and open-handed people launched a charity project. Ludwik Christians, the indefatigable chairman of the Polish Red Cross in Lublin, worked hard to obtain permission to provide weekly supplies of medicines and provisions to the sick Polish internees,52 and his request was granted in March 1943. This generous help, which came as a surprise, could not meet all the needs, but it was definitely life-saving and received with much appreciation and gratitude.

After a few months we managed to establish secret correspondence with Ludwik Christians and immediately asked for larger quantities of a bigger range of medications. Those were dutifully sent, and so our treatment options improved considerably. The Red Cross workers were benevolent and clever people, always eager to help. For instance, we successfully transferred a few pregnant women whose babies were due soon, as well as a few more who had just been delivered, to a hospital in Lublin. The Red Cross sent us straw to fill in mattresses after I had voiced such a need in one of the secret letters. Also, the patients got food parcels for Christmas and Easter. I should really name some of those most willing helpers: Ludwik Christians, Zofia Orłowska, Elżbieta Krzyżewska, L. Jurek; as well as doctors: Cyprian Chromiński, Michał Voit, Aleksander Rybiński, and Sobaczewski.

In autumn 1944 this humanitarian aid campaign was joined by the RGO, the other charity organisation operating in Lublin. Twice a week, we received nourishing dietary soup, rolls with artificial honey, milk, sugar, and the required medications, in large quantities. The RGO also employed people who deserved much respect. I am deeply moved whenever I recall Janina Suchodolska, who used to bring us the provisions and, although she was closely watched by the SS guards, tried to pass on the latest political news. Her resourcefulness and ingenuity were matchless. Acting as a representative of her organisation, she obtained the commandant’s permission to appear in the camp off the schedule, on Christmas Eve, fetching lots of beautifully decorated Christmas trees, Christmas food, and Christmas wafers.53 Janina Suchodolska and Hanna Huskowska smuggled in books for the patients as well as their secret letters, hidden under loads of rolls; the latter job was performed also by their male colleague, L. Jurek from the Polish Red Cross. The efforts of both charity organisations went far beyond their statutory tasks.

Apart from legal charity work, there were also illicit undertakings to save Majdanek prisoners. One of the noble and courageous people who were willing to risk their lives was Saturnina Malmowa, the fearless initiator and leader of all those ventures. In early 1943 she established secret correspondence first with the men’s, then with the women’s camp. The prisoners asked for food, medications, and information. Malmowa got together a team of heroes, who did their best to send in parcels with provisions and pharmaceuticals, sometimes even medical instruments, vaccines, and, importantly, news of the political situation. As our needs were constantly growing, their efforts intensified, and they helped us for the whole time the camp was in operation. Those people had to invest money, time, and work, but also to show dedication and bravery. It required immense persistence and determination to continue such work for a long time, especially as the most lenient punishment, if caught, would have been imprisonment in a concentration camp. Help was provided regularly and unfailingly, in response to the requests made by the prisoners.

Majdanek detainees appreciated not only the courage and commitment of their helpers, but also their manifest kind-heartedness. This is why in their letters to Saturnina Malmowa they addressed her as their “Dearest Caregiver” or “Dearest Mum” (see Figs. 1, 1a, 2, 2a). Some illicit messages of this kind, as well as heartbreakingly modest gifts, sent from the camp as tokens of gratitude, have been preserved.

Charity work was done by many other people as well, who are still practically anonymous, so perhaps I should list their names here: Saturnina Malmowa (aka Mateczka, meaning “Mummy”), Elżbieta Krzyżewska (Córcia, “Daughter”), Antonina Grygowa (Ciotka, “Aunt”), Dr Teodor Lipecki, Dr Michał Voit, the Janiszewskis, the pharmacist Józef Wójcik, Dr J. Adamczyk, Dr M. Woskowski, Jan Supryn, M. Pniewski, J. Dąbrowski, G. Bąbolewska, and Stanisława Warda. Those helpers who are now deceased were Sister Jadwiga of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, and the pharmacist Migurski. My list may be incomplete, so if I have not mentioned some members of Saturnina Malmowa’s team, I beg their pardon: it is difficult to recall all the facts after the lapse of twenty-two years.54 We, survivors of Majdanek, will never forget how much we owe to the local people.

***

Though sketchy and fragmentary, this description of the women’s infirmary at Majdanek clearly shows that we worked in more propitious conditions than could be found in other camp hospitals. The untypical facts were that the SS doctors did not interfere with the treatment, and that we were able to admit and discharge patients at will, which was of paramount importance. While at Majdanek, I thought the situation in other camps was similar. But at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück I saw SS doctors taking an active part in the admission and discharge procedure. I remember the hassle of examining patients in the admission room under the supervision of ferocious SS doctors, the earfuls I got from Mengele and König when the number of discharged patients was “too low,” Mengele’s hospital selections and him sending seriously ill people back to their working units. When my Auschwitz colleagues and I had to live in constant fear for the fate of the patients in our care, I realised that the passivity of the SS doctors in the women’s hospital at Majdanek was beneficial.

This lack of involvement was a rare phenomenon in the camps, and I did not see it in Auschwitz or Ravensbrück. At Majdanek we did not worry so much that our patients could be annihilated, except for the fateful 3 November 1943. Therefore I look up to my Auschwitz colleagues with reverence and admiration, for they worked so hard in the most hostile of environments.

The second asset of the Majdanek women’s infirmary was that it received tremendous humanitarian aid from the region of Lublin. During the last eight months of the hospital’s operations, we had almost all the necessary medications and the women were fed better, some at least in part on the diet that was right for them. The third advantage was that Polish political prisoners arrived on the first women’s transports to Majdanek, and so I was able to recruit good staff: professionally trained and committed, loyal and friendly people of strong moral character.

When we started our work in February 1943 in just one barrack in section V, I had a team of about fifteen people. After a year, the hospital was housed in ten barracks, and I had a staff of almost a hundred. For a few months there were no other doctors but Ada Brudkowska and I, and we would not have managed if it had not been for the highly cooperative nursing staff. The nurses were paragons of diligence and professionalism, and saved many fellow prisoners. So I would like to list their names: Wanda Albrecht-Kowalska, Maria Bielicka, Maria Szczepańska, Stefania Błońska, Kazimiera Bojakowska, Danuta Brzosko-Mędryk, Halina Cetnarowicz, Danuta Cichawa, Zofia Chlewicka, Danuta Czajkowska, Zofia Baseliak, Maria Dworakowska, Janina Despot-Zenowicz, Anna Fularska, Zofia Fabowska-Grzeżutko, Helena Gallowa, Janina Grabska, Wiesława Grzegorzewska, Irena Hołownia, Alina Jankowska, Maria Jaroszewicz, Alicja Kamińska, Jadwiga Korwin-Kamińska, Józefa Kobyłecka, Joanna Kozera, Zofia Krasińska-Leśniakowa, Eugenia Kucierzyńska, Jadwiga Lipska-Węgrzecka, Irena Lipińska, Krystyna Mostowska, Eugenia Matuszewska-Wagnerowa, Hanna Mierzejewska, Barbara Narbutowicz, Antonina Nieszczyńska, Aleksandra Nostitz-Jackowska, Zofia Orlicka, Wanda Orłoś, Wanda Ossowska, Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko, Irena Pełka, Alina Paradowska, Alina Pleszczyńska-Bentkowska, Danuta Plutecka, Irena Peters, Maria Polkowska, Hanna Protasowicka, Maria Rosner, Stefania Rożek, Julia Rodzik, Stefania Sawicka, Zofia Sierant-Wójtowicz, Iwona Stembrowicz, Wanda Ślusarczyk, Janina Ślusarczyk, Halina Śliwińska, Halina Stypułkowska, Stanisława Sobieska, Maria Stpiczyńska, Irena Todleben, Tatiana Trojanowicz, Maria Ulatowska, Ludwika Wiśniewska, Wiesława Warchałowska, Józefa Wdowska, Maria Wierzbicka, Janina Wierzbicka, Matylda Woleniowska, Irena Wartasiewicz, Bronisława Wasiak, Jadwiga Wolska, Irena Zatrybowa, Karolina Żurowska, Maria Żurowska, Hanna Żurowska, Daromira Żenczykowska, and Maria Żupańska.

Three members of this group, Hanna Narkiewicz-Jodko, Zofia Orlicka, and Maria Stpiczyńska, were released from the camp. Danuta Cichawa, Helena Gallowa, Anna Żurowska, and Maria Żupańska died in the camp. Hanna Protasowska, Zofia Sierant, Kazimiera Bojakowska, Maria Rosner, and Tatiana Trojanowicz died soon after the war. Our certified nurses are still professionally active, except for Wanda Orłoś, who is unable to work because of poor health. Six of the teenagers who came to value a carer’s work while in the hospital have become doctors; they are Wanda Albrecht, Danuta Brzosko, Halina Cetnarowicz, Hanna Fularska, Maria Jaroszewicz, and Irena Wartasiewicz. Joanna Kozera, a teenage prisoner from Radom, is now a certified nurse.

I hated Majdanek and it still gives me nightmares. Yet I fondly and vividly remember the hospital, the patients, and my staff. Nearly twenty-five years have passed, but the friendships that developed in the camp stand firm, as they did at Majdanek. Such relationships are invaluable, because the price we paid for them was inestimable.

In the camp, where most women had to perform backbreaking physical labour, working in the hospital was considered a light job, and rightly so. We stayed indoors, where the temperature was bearable, so we did not get wet or freeze outside for hours, we were not beaten by SS supervisors and did not have to do useless, stupefying, and exhausting tasks. The most important thing was that we were able to use our professional skills to help fellow prisoners recover. This understanding gave us moral strength, because we could find some significance and sense in our camp life. Therefore it can be said our profession allowed us to survive, which we fully appreciated. This realization was with us then, and has stayed.

Perhaps it was only in the camp that we so palpably felt the value of our medical profession. But on the other hand, in no other place and at no other time did we feel as much helplessness and inner protest as when we saw our vulnerable patients being sent to their deaths or, when dead, being treated disrespectfully. Death was a common thing in the camp, and so was contempt for a dead body. But that did not diminish the dignity of the persecuted prisoners, quite on the contrary, their deaths seemed even more majestic and sublime.

No camp survivor can ever forget that.

Translated from original article: Stefania Perzanowska, “Szpital obozu kobiecego w Majdanku.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1968.

- This date refers only to the establishment of the women’s camp. The men’s concentration camp at Majdanek was established in the autumn of 1941 and the first prisoners were Russian POWs. From May 1942 the camp’s main purpose was the extermination of Jews. At that time the number of registered internees was about 40,000, and most of them were Poles. But those who were sent straight to the gas chambers were never registered, and their bodies were burnt either in the crematorium or in Krępiec Forest nearby. Out of the overall number of 300,000 prisoners at Majdanek, about 160,000 died. Also, 200,000 Jews were killed there. On 3 November 1943, 18,000 of Lublin’s Jews perished during what the Germans called Erntefest (“harvest festival”).a

- January 1943 was the month when the first Polish female political prisoners from the Radom, Częstochowa, Kielce, Skarżysko-Kamienna, and Warsaw prisons arrived at the camp. The decision to establish a women’s camp in Majdanek was taken in the late August 1942. The first women to be interned there in October 1942 were persons displaced from Dziesiąta and Wieniawa (quarters of the town of Lublin). The men’s camp was initially intended for Soviet POWs and its construction started during the autumn of 1941. Until late 1942 only prisoners fit for work, mostly Jews and Polish hostages, were interned there. Gas chamber killings started in September 1942 and the first victims were typhus patients and the extremely emaciated. Death selections of entire families and murdering of Jews considered unfit for work, including children and the elderly, commenced in November 1942. In total, there were about 150,000 prisoners of various nationalities interned at the camp. The Jews, amounting to almost 80,000 people, were the largest group, with about 35,000 Poles being the second largest one. Conservative estimates of the camp’s death toll include about 78,000 people, including almost 60,000 Jews.b

- The women’s camp field, as well as the four men’s field, were all subject to one camp commandant. Oberaufseherin (chief overseer) Else Ehrich enjoyed the greatest authority in the women’s field, with all the other female overseers held accountable to her.b

- At Majdanek, a section of the camp was called a “field” (Pol. pole).a

- A transport of political prisoners, including women, from the Pawiak prisoner, arrived at Majdanek on 18 January 1943.b

- This so-called Radom transport included persons from prisons and jails in Kielce, Skarżsko-Kamienna, Częstochowa, Radom, and Piotrków. They arrived at Majdanek on 7 January 1943. This was the first official transport of political prisoners to the camp.b

- The tasks of the prisoner medical team included providing simple care for the less severely ill in the residential barracks, assisting childbirths, dealing with the women’s transport arriving, and with the women’s bathhouse. The team was initially directed by Hanna Protassowicka, and later by Zofia Chlewicka.b

- Since late April 1943 the Jewish women from the Warsaw Ghetto were the majority of the women prisoners of Majdanek. Right after the transports from the Warsaw Ghetto, in May 1943 about 11,000 women were imprisoned in the camp, which constituted the greatest numbers of women detained there at the same time. The number then decreased to 8,000 in June and 6,000 in August.b

- When the Germans occupied Poland, they closed down all the secondary schools, colleges and universities. The Polish underground resistance movement set up a system of secret education, which was illegal from the German point of view.c

- His actual full name in a correct spelling was Wilhelmi Reinartz. An SS orderly in Majdanek since August 1942, he was one of the very few performing this function who actually tried to help the prisoners. Reinartz brought books and medicines from the inhabitants of Lublin to the prisoners, which was later brought to his defence by witnesses during his first after-war trials. Later Reinartz was brought to court again as part of the trial against the SS staff of Majdanek in Düsseldorf but he was released due to illness.b

- Actually Anna Marder. A medical student from Vilnius, in mid-April 1943 she was transported from the Grodno getto to the Treblinka extermination camp alongside her husband and mother, Szejna Orlis. Having survived the death selection there, Marder and her husband were sent to Majdanek, while her son and Szejna Orlis had been killed.b

- An ambiguous expression, which may mean she was to be moved to another camp, but it could also mean she would be sent to the gas chamber.c

- Transports of the families from the getto due to its liquidation took place between 28 April and mid-May 1943.b

- Max Blancke, SS-Hauptsturmführer and doctor of medicine, from July 1940 on performed the function of an SS physician in a number of concentration camps (Dachau, Buchenwald, Oranienburg, Ravensbrück, Natzweiler). He was the SS Chief Physician of the KL Lublin (Majdanek) concentration camp from April 1943 to January 1944. Afterwards he was sent to KL Plaszow, where he worked as an SS physician until August 1944.b

- Alina Brewda, a practicing gynaecologist before the war, was transported to Majdanek after the fall of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Afterwards she was moved to Auschwitz (in January 1943), and later (1944) evacuated to Ravensbrück and Neustadt-Glewe.b

- Else Ehrich (1914-1948). War criminal. Worked in several concentration camps as an SS-Aufseherin. After the war put on trial before the Lublin court, sentenced to death, and hanged in 1948.c

- Anna Braude-Heller, a paediatrician, was not a Majdanek prisoner. She worked in the Warsaw Ghetto Hospitals and was one of the first to investigate the hunger disease. She died in the first days of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.b

- Actually Irena Grodzieńska, a Warsaw internist.b

- Najburzanka (also known under the name Najbużanska), an assistant surgeon at the Leszno hospital in Warsaw.b

- Actually Alicja Piotrowska-Przeworska née Glazer. She was a paediatrician at the Leszno hospital in Warsaw. She was not a Majdanek prisoner and survived the German occupation.b

- Szejne Orlis, A. Marder’s mother, was killed in the Treblinka extermination camp.b

- Antonina Wdowińska née Berger, a stomatologist.b

- Possibly a reference to Mrs Altszul (or Aldszuld), a medical nurse from the Leszno hospital in Warsaw.b

- A senior nurse from Warsaw, she was probably transported to the Treblinka extermination camp in January 1943.b

- While in Majdanek, Hellena Gallowa was able to hide her Jewishness with the help of falsified documentation. She was employed in the office of the camp hospital. When the Germans looked for the hiding Jews after the Erntefest executions, an investigation revealed Gallowa’s ethnicity. She was shot in the camp in January 1944.b

- A nurse. The correct spelling of the name is Isserlis.b

- A nurse. The correct spelling of the name is Mebel.b

- Actually Rosa Gilerowicz-Odesowa (Odess), a nurse.b

- A reference to the transports of families (about 8,000 persons, mostly women and children) displaced from Belarus between March 1943 and January 1944.b

- On 25 February 1944 a transport of POWs from the Chełmno extermination camp arrived at Majdanek. The transport included about 60 women, many of them doctors, orderlies, and medical assistants. Four doctors from the transport volunteered to work in the camp hospital (three names are known: Nadia Pawlenko, Lidia Simbircewa, and Maria Grigoriewna Andriejewa). All the four were transported to Ravensbrück in April 1944.b

- SS-Oberscharführer, baker by profession, member of the SS staff in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and Flossenbürg. He stayed at Majdanek from November 1941 to May 1944 and was the director of the crematorium and the leader of the commando which burnt the prisoners’ corpses there. He participated in the selections for gas chambers and executions. He was sentenced to death executed on 24 January 1948 in Kraków.b

- An SS orderly, he worked at Majdanek from 1942 to 1944. Konietzny was tried in the Düsseldorf trial (1975-1981) but he was granted a release due to illness.b

- Full name Franz Hermann Bodmann. An SS-Obersturmführer and doctor of medicine, he was an SS physician in Neungamme, Auschwitz, Majdanek, and Natzweiler. Bodman died by committing suicide in 1945.b

- Max Blancke. SS-Hauptsturmführer and doctor of medicine, from July 1940 on performed the function of an SS physician in a number of concentration camps (Dachau, Buchenwald, Oranienburg, Ravensbrück, Natzweiler). He was the SS Chief Physician of the KL Lublin (Majdanek) concentration camp from April 1943 to January 1944. Afterwards he was sent to KL Plaszow, where he worked as an SS physician until August 1944.b

- Heinrich Friedrich Rindfleisch (1919-1969). SS doctor; practised criminal experiments. After the war wanted by the Polish, French, and Belgian authorities for war crimes, but never brought to justice. Continued to practise medicine in West Germany after the war.c

- Full name Heinrich Rindfleisch. An SS-Obersturmführer and doctor of medicine, he was an SS physician in Ravensbrück, Majdanek, Kl Plaszow, Gross-Rosen, Mittelbau, Sachsenhausen, and Bergen-Belsen. After the war Rindfleisch was never tried and worked as the chief surgeon of the Rheinhausen hospital.b

- Josef Mengele, SS-Hauptsturmführer, SS physician in Auschwitz-Birkenau. He carried out the death selections and criminal medical experiments. Having escaped to Argentina after the war, Mengele was never tried.b

- Fritz Ernst Fischer, SS-Sturmbannführer, SS physician in Ravensbrück. Fischer assisted in Karl Gebhardts criminal surgical experiments on women prisoners. After the war he was tried in Nuremberg and received a life sentence, shortened to 15 years in jail in 1951. Granted a conditional release in 1950, in 1955 he was fully released.b

- Karl Gebhardt, SS-Sturmbannführer, Heinrich Himmler personal physician and president of the German Red Cross, responsible for criminal experiments on prisoners in Ravensbrück and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Gebhardt was tried in Nuremberg, sentenced to death by hanging, and executed afterwards.b

- The death selections in the women’s field included Jewish women only and they were the ones murdered in the gas chambers.b

- On 3 June 1943 there was a transport of Greek Jews suffering from malaria from Auschwitz to Majdanek, including 302 women.b

- Rada Główna Opiekuńcza, the Main Council of Relief, the only Polish charity organisation recognised by the Germans in occupied Poland.c

- From 30 June to 14 July 1943, 8566 persons displaced from the Zamość, Hrubieszów, Biłgoraj, and Tomaszów poviats were sent to Majdanek.b

- In July and August 1943 entire displaced families, amounting to 5,600 persons, were sent to perform forced labour in the Reich. The remaining 2106 were released from the camp thanks to the efforts of Rada Główna Opiekuńcza and the Polish Red Cross.b

- Between 12 December 1943 and 21 March 1944 the so-called sick transports were sent to Majdanek from the camps in the Reich. The transports amounted to about 7,000 prisoners for whom the Nazis intended to create a so-called reconvalescent camp. The transport of about 800 women from Ravensbrück arrived on 9 February 1944.b

- At that time there was not yet a gas chamber in Ravensbrück. Sending women prisoners to Majdanek was connected to the plans of establishing a “reconvalescent camp.” b

- Thanks to the efforts by the Polish Red Cross and Rada Główna Opiekuńcza, since February 1943 the camp authorities agreed to the receiving of food parcels (but only by the Polish prisoners).b

- Actually Marie-Josée Soleme, a nurse from Brussels, interned in Ravensbrück for her participation in the resistance movement. In the camp she was assigned to the commando pushing coal wagons, due to which she fell ill with spinal tuberculosis and paresis involving lower extremities. Deemed unfit for work, she was transported to Majdanek. Having been taken care of by Dr Perzanowska and her staff, Soleme’s health improved. Afterwards she was sent to Auschwitz where she stayed until the liberation.b

- An epidemic of typhoid fever broke out in Majdanek in the late 1941. It reached the women’s camp after the arrival of the first political prisoners.b

- According to the extant camp records the number was rather 230 women, including the ones from the Revier: 180 patients and 50 members of the staff.b

- There was illicit secret correspondence in the camp. Secret messages, known under the Polish name grypsy, were written on paper shreds and smuggled with the help of some non-prisoners working in Majdanek. This enabled communication between family members as well as between the interned resistance movement activists collaborating with conpiratory organisations outside the camp. If any grypsy were found, a prisoner in possession of them was whipped, and non-prisoner workers were imprisoned in the camp.b

- Only after the arrivals of political prisoners did the camp authorities agree to have the care extentded to the interned. On 26 February 1943, during the meeting of, among others, the vice-president of Rada Główna Opiekuńcza Henryk Woroniecki and Hermann Florstedt (Majdanek’s commandant at the time), it was agreed that the camp kitchen will be provided with food products in common boilers. Apart from that, there were to be provisions of straw for the pallets and medicines according to the requirements reported by the camp physicians. All the agreements concerned only the Poles imprisoned in Majdanek. The operation of helping them was conducted by Rada Główna Opiekuńcza alongside with the Polish Red Cross and its president Ludik Chrystians.b

- One of the Polish Christmas traditions is to “share wafers,” exchanging wishes on Christmas Eve.c

- The help provided to Majdanek prisoners was more often than not based on spontaneous acts of individual people, who often were not even in any kind of touch. S. Malmowa did not coordinate these actions.b

a—notes translated from the original; b—notes by Marta Grudzińska, a Medical Review Auschwitz Expert Consultant; c—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, the Head Translator.