Author

Tadeusz Karolini, MD, PhD, 1907–1976, microbiologist, internist, pharmacologist, and epidemiologist, survivor of Dachau and Gusen (prisoner no. 6706).The sub-camp in Gusen, and especially its sanitary issues, has already been discussed in a number of papers published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. One of the authors of these publications was Dr Zbigniew Wlazłowski, who gave a detailed account and bibliography related to this camp in his memoirs entitled Przez kamień i kolczasty drut. In June 1966, I sent him my description of the beginnings of the prisoners’ hospital in Gusen. The present paper is based on my own notes and correspondence and on the three-part recollections of Stanisław Nogaj entitled Gusen – pamiętnik dziennikarza.

Nogaj recounts that since ancient times there have always been stone quarries called “Gusen” at Langenstein, in the district of Perg, Upper Austria. There is also a small river of the same name that flows into the Danube south of the quarries past the village of Langenstein. In 1939, Langenstein had a population of 1,800; up to that time the Gusen quarries were privately owned by several local farmers. During World War II, the quarries and the adjacent area were acquired by DEST (Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH, the German Earth & Stone Works Company), an SS-owned business. DEST began mining the quarries using the slave labour of prisoners from Mauthausen, a concentration camp three kilometres (just under 2 miles) away from the Gusen quarries. DEST did not care about work efficiency, since the chief aim of the SS use of this quarry was to murder prisoners from the concentrations camps in the neighbourhood.

In 1940, DEST purchased more property in the environs of the Gusen quarry and erected administrative and residential barracks. Also, they decided to build a special camp for Polish prisoners there. The new sub-camp was to accommodate 10 thousand prisoners. Barracks for SS troops were set up outside the camp. The prisoners’ camp had 32 barracks, each for 300 inmates; latrines and washrooms were built between the barracks, and bathhouses and a crematorium at the back. A prisoners’ kitchen was located next to the roll call square.1 In 1944, the number of prisoners’ barracks rose to 36. The influx of new prisoners was so high that a second camp for another 10 thousand was built west of the original site. It was called Gusen II, a sub-camp of Gusen I. It was difficult to get in touch with the inmates of Gusen II because they were separated off from the rest of prisoners in Gusen. In 1944, another small camp was set up in Lungitz, with a bakery employing 250 prisoners.

Prisoners’ labour was also used to build a large complex of industrial and residential estates for over 2,500 German soldiers and non-commissioned officers, offices, SS kitchens, canteens and SS officers’ messes. The whole complex, designed and constructed by prisoners exploited to the maximum, was located in the environs of the camp. The prisoners’ labour force was also used to build a large housing estate for SS officers’ and non-commissioned officers’ families, and numerous civilian specialists in the town of St. Georgen (3 km west of the camp). Sports grounds, shooting ranges, and special barracks for foreign workers were also set up.

DEST expanded, growing into an enterprise worth millions of reichsmarks. The company bought the Kastenhofen and Pyrchbauer quarries and erected what they said was the world’s largest Schottersilo (stone crushing plant), as well as huge administrative buildings, workshops and spacious stone processing halls in Gusen and St. Georgen.

In 1943 the Steyr, Messerschmitt, Rüstung Wien und Esche industrial and armaments companies started business in Gusen. Dozens of giant production halls were built (some of them underground) for a workforce of 16 thousand prisoners. A railway line was laid connecting St. Georgen with Gusen and Wiener Graben.

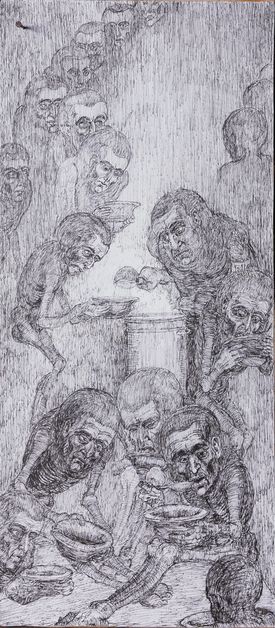

Over 200 thousand prisoners from thirty-one nations were held in Gusen in the course of five years. Over 40 thousand prisoners of various nationalities, including over 20 thousand Poles, were murdered there in 1940–1945. In the opinion of Antoni Gościński, one of the prisoner-doctors in Gusen, the SS camp authorities used 80 different methods of mass killing. In fact, every square inch of the land around Gusen was soaked with the blood and tears of countless prisoners; their torment and suffering hallowed virtually every spot in Gusen.

The land around Gusen is fertile and rich, as for five years its soil was “enriched” with the ashes of the prisoners’ bodies burned in the crematorium and the smoke emitted into the atmosphere from its chimney. Yet, the name “Gusen,” is not to be found on the map of the world, and hardly anyone has heard of it. Nonetheless, the place has gone down in history as the Mauthausen–Gusen concentration camp. On 1 January 1940, Gusen was classified as a third-degree Vernichtungslager, the heaviest category of the death camps. Its prisoners did not even receive new numbers, they wore the old ones from their previous concentration camps.

Gusen was liberated by American troops at 5:00 p.m. on 5 May 1945. To commemorate this event, every year on the fifth of May Mauthausen-Gusen survivors meet at five in the afternoon in Katowice, Poland. They gather around the 30 cm x 20 cm cylindrical bell with a characteristic clapper, which was forged by prisoners and hung in the roll call square in Gusen. After the liberation of the camp, survivors brought the bell to Katowice. Now it tolls in tribute to their murdered fellow inmates. It carries a beautiful symbolic, thought-provoking inscription:

Day or night

Always with might

The bell rings:

It’s a sign:

Your duty begins.

Ob Tag ob Nacht

Stets mit Bedacht

Der Glocke Ruf erklingt

Ein Zeichen

Deine Pflicht beginnt.

In the abnormally heavy working and living conditions calling to mind the circles of Dante’s Inferno, every prisoner struggled to maintain their strength and save their life, to survive and see the longed-for freedom. So it is not surprising that their eyes looked to the prisoners’ hospital for solace and security. Initially the hospital was an infirmary and an outpatient emergency centre. The beginnings of the Gusen hospital were closely related to the larger and larger transportations of prisoners brought to the camp.

Stanisław Nogaj wrote in his diary that when he arrived in Gusen on 26 May 1940, in the first transportation of Polish prisoners from Dachau, the sick inmates were left in their barracks. When the second transportation arrived from Dachau on 6 June 1940, in which I came to Gusen, the hospital was already working in Block 24, which was no different from other prisoners’ barracks. It consisted of two rooms, A and B. Room A was on the side facing Block 16 (the penal commando), room B was opposite room A. Patients lay next to each other on straw mattresses spread out on the floor; the entire block could accommodate 300.

At the entrance there was a simple toilet facility consisting of barrels outside the block. The penal commando carried out the contents in tanks. In room B there was a timbered precinct called Himmelkommando (“Commando Heaven”), where patients suffering from bloody diarrhoea were put to die: they were killed with petrol injections given intravenously or into the heart. Room A accommodated surgical patients; its Stubedienst was Franz Zach from Schwarzwald near Vienna, a “green triangle”2 who was a butcher by profession, convicted for stabbing his foreman at work.

Room B was for diarrhoea patients, and the block leader was Heinrich Roth, a political prisoner with a red triangle,3 known for his violence and brutality to inmates. In July 1940, the hospital got two extra blocks. A surgical ward and dispensary were established in Block 29, whereas Block 30 housed an internal diseases unit. The whole of Block 24, which was called the Scheisserei (the shit-house) was left for patients suffering from severe diarrhoea; its block leader Roth ran it for a year until his death. According to Nogaj’s notes, Roth developed a high fever and was killed with a phenol injection on orders from SS physician Kiesewetter.

Block 29 consisted of rooms A and B. A had around 70 beds for surgical cases. Dr Antoni Gościński, a prisoner doctor from Poznań working as an orderly, had a small cubicle and bed there. Room B served as an outpatients’dispensary and admissions room; it had a separated off area with a simple surgical table, a cabinet with surgical and dental instruments, and a pharmacy dispensing medicines and dressings. There was also a small physiotherapy room with a Solux lamp, a small quartz lamp, a Lichtkasten,4 and a lab table with several reagents for testing urine and sputum, and a microscope.

The hospital kapo Franz Zach, his Schwung5 cleaner Staśko Pecko from the Suwałki region, the hospital barber Klemens from Gdańsk, and Jankowski from Poznań, who was the barber’s assistant and worked as an orderly, lived in a “private” precinct screened off with a curtain of blankets. There was also an external orderly, Józef Pończa, a surgeon from Bielsko, who worked part-time in the hospital from July to mid-August 1940. Later he was released and allowed to return home.

Block 30 housed patients suffering from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as patients with tuberculosis, whose condition was carefully kept secret since such patients were likely to get a petrol or phenol injection to eliminate the source of infection. There were also patients with oedemas all over their body, especially hunger oedemas, patients with urological problems, and numerous other prisoners who were extremely emaciated and devoid of any vital strength from overwork.

Albin Garbień, a gynaecologist from Cieszyn, worked as a part-time orderly in room A and as the chief orderly in Block 24 (the diarrhoea unit). He was released in September 1940. Another inmate, Wiktor Gospodarczyk, a miners’ foreman from Karwina Frysztat,6 lived and worked as an orderly and cleaner in room A. Władysław Duława, a doctor from Jaworze near Bielsko, was employed as an orderly in Block 13 and part time in room A of Block 30. He started working in the hospital in late August 1940. I am still in touch with all of them. Our friendship started in the camp, where we did our best to save patients in the prisoners’ hospital and to support other prisoners. Block 30 had between 70 and 80 beds in each room. Blocks 29 and 30 had separate toilets in the hallways at the entrance; the sewage tanks were under the floor and were emptied by the penal commando.

The hospital, then consisting of three blocks, Nos. 24, 29 and 30, was managed by the hospital kapo, Franz Zach, who lived in Block 29. The hospital clerk was Johann Gruber, who held doctorates in philosophy and theology, and had been a lecturer in the Linz seminary. He was a “red triangle” (a political prisoner) and was on friendly terms with Polish inmates. According to Nogaj, Gruber died a cruel death: he was beaten up and hanged on 7 April 1944.

Prisoners’ bodies were disposed of by the Leichenkommando (corpse unit) supervised by the block leader Roth, who lived in Block 24. The kapo of this commando was Henryk Kolon from Katowice, who collected all the corpses in Block 27 for transportation to the Mauthausen crematorium in reusable coffins which were kept in that block as well as in Blocks 29 and 30 next to it. The Leichenträger (corpse carriers) were Pusz from Strumień near Cieszyn; Tadeusz Twardzik, a commercial college graduate; and Władysław Buliński, an industrial college graduate; both of them came from Czechowice-Dziedzice. In August 1940, they were moved to Block 29 to work as cleaners for kapo Franz Zach; they lived in Block 13, where I made their acquaintance. Prisoners were made to dig foundations for a crematorium which was to be located between Blocks 25 and 17, and between Blocks 26 and 28, and foundations for a bathhouse between Blocks 27 and 19, and 28 and 20—it was the notorious bathhouse where prisoners were killed with cold water showers.

The last blocks, 31 and 32, were the Effektenkammer, a store-house for prisoners’ personal clothes and possessions, prison gear, uniforms, as well as shoes dispensed to prisoners when the need arose. It was the place where prisoners due for release were issued with civvies. In addition, those who were transferred to other camps or sent to Mauthausen to be shot had to report in these blocks before transportation.

In early September 1940, while I was working full-time in Block 12, I was sent in to work as a part-time orderly in the hospital under the supervision of kapo Franz Zach in Block 29. Compared to my previous hard labour in the Kastenhofen, Gusen and Westerplatte quarries, the job in the prisoners’ hospital was like a dream come true, despite the great risk of being harassed if you tried to offer any form of help, not only medical assistance. Now I could start a new chapter in my medical career in the camp, this time in an official medical facility, although at the time prisoner-doctors could only work as orderlies and kept quiet about their medical qualifications, so as not to let the SS know—there was a prohibition on the employment of medical professionals.

The admissions and methods of treatment followed a camp-specific daily procedure. The day began with an early roll call in the square. Patients who had been shortlisted in the barracks walked to the hospital and stood in a line in front of Block 29. Kapo Franz asked each of them the same question, “Hast du Scheisserei?” (Have you got the shits?); those who said yes were immediately sent to Block 24 (the diarrhoea unit). The kapo qualified the rest for outpatient or emergency care. All the SS doctor did was to confirm the new admissions when he made his rounds of the patients’ rooms. Next the medical staff conducted surgeries. Franz was quite good at surgery, for example, when he assisted the SS doctor during operations he had no trouble stopping a vascular haemorrhage.

The instruments were not sterilized by boiling, but wrapped in lignin and immersed in a lysol solution for immediate use, just as barbers do with shaving razors. The gauze bandages were not sterilized, either; patients got pieces of gauze ready for immediate use in surgery. No wonder that purulent infections proliferated.

After the midday meal, when prisoners went back to work, outpatients came in to have their dressings changed or for a tooth extraction. These minor surgeries were performed by kapo Franz himself. The staff dispensed antipyretics and sulphonamides. We could count on our fellow inmate Henryk Grzęda, a former student of Gdańsk University of Technology, who was employed in the SS pharmacy and often managed to smuggle medications such as vitamins, cardiac agents as well as antiseptics and disinfectants into the prisoners’ hospital.

Bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infectious skin diseases spread in the camp, since prisoners could not take a bath; their underclothes were washed every two or three weeks, but even then, they were still lice-ridden. We tried to apply various ointments to treat skin diseases effectively, always with Franz’s consent. Of course, we had to convince him we were using the right methods of treatment and administering them skilfully. Outpatients were exempted from work for a certain period of time, and had to show Franz a Stubendienst certificate that they were off work. We had to use various tricks to persuade Franz to keep extremely emaciated inmates on less strenuous jobs, such as cleaning their barracks, for a longer time.

Diverse treatment was used in the prisoners’ hospital: medications were administered orally and as injections, especially given to patients suffering from oedemas. The most effective treatment was high-calorie food, like oatmeal and rice pudding cooked in milk, as well as quiet and rest, a toilet nearby, i.e. not having to go outside and risking a beating on the way to the latrine. In such relatively good conditions patients recovered from extreme emaciation. However, in Block 24 (the diarrhoea unit) the death toll was very high, especially during the autumn epidemic of dysentery. Our colleagues did their best to save as many lives as possible in this block, and many patients evaded certain death at the hands of the brutal block leader Roth. At this point, I would like to mention the work of the field orderly Józef Wałach, a doctor from Bielsko, who used to take a bag full of dressing materials to help prisoners working at the Kastenhofen outcrop. In this job, he avoided violent assaults by the brutal functionaries, while at the same time providing professional assistance to prisoners liable to sustain various types of injuries in the quarry.

The prison hospital was supervised by the Lagerarzt (SS physician). According to Nogaj’s diary, in July 1940, this appointment was held by Krieger, who limited his duties to signing death certificates. Untersturmführer Schildbach was appointed to the job in August 1940, and promoted to the rank of Sturmführer in October. Hauptsturmführer Krebsbach served as an SS consulting doctor, and usually came in from Mauthausen once a week. As a rule, he operated on patients with severe phlegmons (acute inflammation of the soft tissue) and examined certain other patients. Dr Schildbach performed surgeries on an everyday basis, assisted by Kapo Franz, who helped very skilfully to stop the bleeding from injured organs. “Incurable” patients were killed with petrol jabs by the Kapo himself. Of the non-commissioned officers who were the SS doctors’ assistants, I remember one who did not want to believe me that I was only a nurse by profession—he observed me administering an anaesthetic and arranging surgical instruments. He was sure I was a doctor.

It was not until evening that the tense atmosphere relaxed and the hospital became a relatively quiet and restful place. The Prominente (big shots), such as kapos, block leaders, and even Dr Kammerer,7 looked in for advice. They were very worried if they had to undergo minor surgery and could not stand the sight of blood or were afraid of pain. But they listened to us and followed our medical advice. Many of these butchers were taken down a peg or two after a surgery, but once they recovered they went back to their old tricks. In the evening there was choral singing; someone played the harmonica, which was soothing both for the patients and the medical staff; even the guards’ faces softened up. This was the time when medications and surplus food could be smuggled into the blocks. We were in touch all the time with prisoners working in the camp kitchen, so we could count on supplies of vegetables: onions, carrots, cabbage, and bread, which we exchanged for medicaments, to help our patients stave off vitamin deficiency. Our medical skills and services helped us keep our jobs in the hospital. Kapo Franz suffered from keratitis (long-term corneal inflammation) of his left eye and had to wear an eye patch. I tried to treat his eye condition as well as his paroxysmal arrhythmia and tachycardia. Apart from drug treatment, Franz needed to take vitamins.

All the deals had to be conducted in absolute secrecy. Although the kapo of the kitchen and the kapo of the hospital were our friends, they didn’t want to know about our barter business. Our main concern was not to get caught, otherwise we would have been sent to the penal commando in the quarry. This happened to a doctor from the Poznań region who was working as an orderly in the hospital but did not take due care, and got caught red-handed with a couple of aspirins from the pharmacy on him.

Moreover, we liaised with fellow inmates working in the politische Abteilung (political department). They came by in the evening, passing on the information that had been added to our files; they let us know when someone who was a friend of ours was due to be released. Usually it was our colleague Duława who brought the good news to the inmate about to be released. He told him jokily that his news was like fortune-telling, but it always turned out to be true.

In November 1940, when the quarantine for dysentery was over, many prisoners were released or moved to the main camp in Mauthausen. Later we learnt that they had all been executed. They were prisoners from Warsaw, and they all had a death sentence. That was the fate of my friend Stefan Smolec, a lawyer who had been president for three terms of office of Bratnia Pomoc, a students’ union [and fraternity benefit society—Website Editor’s note] at the Jagiellonian University, Kraków before the war, and was later employed in the Polish Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare in Warsaw. He was arrested on 11 April 1940 in Warsaw, sentenced for his underground activities and shot on 21 November 1940 in Mauthausen. Groups of these prisoners were in the shoddiest prison gear when they were taken to an unknown destination. The SS authorities denied rumours that they had been shot. Speaking about it was prohibited and punishable. All the Varsovians deported to Gusen were killed—there were a few dozen of them. Only one is believed to have survived and returned home. Apparently, he told Stefan Smolec’s family in Kozy near Bielsko-Biała that Stefan had been killed. Stefan Smolec will be remembered as an outstanding student activist of the Jagiellonian University and one of the pioneers of its Oleandry hall of residence.8

One of our riskiest secret practices in the hospital was to hide the unhealed injuries of patients who were to be released. It was a challenge for us to present a patient ready for discharge from the hospital, so that the SS doctor would not notice the camouflage of his injuries. Although Franz was on our side and let some prisoners be released, our practice, which was strictly prohibited, could have been exposed. We made all the released prisoners promise not to tell anyone how they got their injuries and to lie to their families about them. Otherwise we would have ended up on the beam,9 hung up by the arms and flogged to death.

We could pass messages to our families and friends through the services of the released inmates, who had to memorise what they were to say to our relatives. Once a message to my wife could have boomeranged on me. Namely, she sent me a parcel with a warm pullover inside, and I had to make excuses in the political department that she had done it of her own accord, with the loving care she had always shown to me at home, so that I could have a warm winter garment. After listening to my story, the SS-man let me keep the pullover, but at the same time he warned me that he would not be so lenient with me the next time. I gave this pullover to Kapo Franz, which he accepted with great joy and satisfaction. I wanted him to continue turning a blind eye to what went on when prisoners were discharged.

1940 was a very hard year and a turning-point for all the prisoners confined in Gusen. What was the extent of our help offered to patients in the hospital? Without exaggerating, we may say that it was huge, but it also involved a colossal risk. We saved many lives in the hospital working in primitive conditions and with the poor means at our disposal. Let me give the example of Father Jan Masny from Grodziec near Skoczów. This ex-military chaplain was bullwhipped, receiving 139 strokes, and his buttocks looked like a chopped schnitzel. We treated him for three months and he recovered and was released from the camp; I was released with the same group of inmates.

It would be impossible to describe all our medical activities in the hospital. It should be remembered that doctors were not allowed to work there, so officially we were employed as medical assistants. As lab assistants, we had to identify blood types for the SS-men and tattoo them on the inside of their left arm. We were doing blood type tests already in September 1940.

The prisoner doctors working as paramedics were a clandestine medical team that organised a proper prisoners’ hospital and became its staff. Others observed our work and learned how to treat the sick and ensure the most effective help, especially in emergencies. This was how the auxiliary medical staff was trained. On the other hand, our instinct of self-preservation helped us avoid serious infections, urged us to observe the rules of personal hygiene and safety at work, and develop a sense of solidarity with one another.

The day of my release came. I was discharged with the largest group, a few dozen prisoners released on 28 November 1940. We left the camp with mixed feelings, which we later put into a song—the march of the erstwhile political prisoners, which has become the Gusen survivors’ anthem:

The terror ended

and the world’s face changed.

Our father’s house

awaits our return.

We will go there on a bright day

with new strength.

So say goodbye to

the world of stone blocks.

Finally, let me add that the lyrics were written by Konstanty Ćwierk, a Gusen prisoner who died in the camp, and the tune was composed by another Gusen prisoner, Gracjan “Jasio” Guziński.

Translated from original article: Karolini, T., “Początki rewiru w Gusen.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim; 1976.

Notes- For a schematic diagram of Gusen I concentration camp, see Wlazłowski’s article “The Gusen prisoners’ hospital.”a

- In Nazi German concentration camps prisoners convicted of criminal offences wore a green triangular badge on their prison gear.b

- Political prisoners and Poles wore a red triangular badge.b

- Lichtkasten—a chest fitted with light bulbs; a patient sat inside the chest and was given an electromagnetic radiation treatment with the light from the light bulbs.a

- A juvenile prisoner who was the kapo’s sexual partner.a

- Between the World Wars this part of Silesia was a disputed territory, claimed by Poland and Czechoslovakia, and straddled the border between the two countries. The Czech place-name is Karviná-Fryštát.b

- Dr Kammerer is mentioned in Stanisław Kłodziński’s article on Dr Janina Kościuszkowa.a

- For the history of the building, now known as the Żaczek students’ hall, see http://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/szklany-dom-3/.a

- The beam—a wooden structure similar to a gallows and used for torture.a

a—notes by Maria Kantor, translator of this article; b—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator of the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

- Wlazłowski, Zbigniew. Przez kamień i kolczasty drut. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie; 1974.

- Nogaj, Stanisław. Gusen – pamiętnik dziennikarza. Katowice and Chorzów: Komitet Byłych Więźniów Obozu Koncentracyjnego Gusen; 1945.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.