Author

Zbigniew Wlazłowski, MD, 1916–1996, survivor of Buchenwald and Gusen (prisoner no. 49943), author of concentration camp history-related medical articles and memoirs.

Structure and organisation1

The Gusen prisoners’ hospital was designed and organised like other hospitals Nazi Germany set up in its concentration camps. It was a camp within the camp. The prisoners’ hospital in Gusen consisted of a group of barracks on the premises of the main camp, but it was surrounded by an additional barbed wire fence. There was a guard at the entrance, and his duty was to admit only the hospital staff and patients, who had to be escorted by an orderly or a kapo.

Patients and hospital staff were subject to the authority of the German Lagerarzt (SS camp physician), who had absolute power and control over all the hospital’s activities and undertakings. Even the camp’s commandant did not have the right to issue orders concerning the hospital without the Lagerarzt’s knowledge and consent. The Lagerarzt was assisted by two Blockführers (block leaders), who were SS non-commissioned officers serving as orderlies.

The hospital had its own office, called the Schreibestube, where the hospital clerks kept the patients’ and staff records as well as a register of deaths. They also sent death notices to the families of the deceased. Following the Lagerarzt’s order, they gave bogus causes of death, such as “died of a heart attack, pneumonia or in an accident at work,” on the death certificates of those killed in mass executions.

Separate roll calls were conducted in the hospital, in which the patients were counted first by the hospital clerks and then by block leaders, and the count was announced during the general roll call of the whole camp.

Although the patients’ food was brought in from the camp kitchen, it was slightly different from the rations for the remaining inmates. Besides soup, which was served to all prisoners, the patients received a small portion of white bread and a little “dietary” soup thickened with flour or over-cooked groats. These extra portions were provided primarily for propaganda reasons, since from time to time the camp authorities allowed the Red Cross commissions to visit the hospital.

The “hospital kapo” held the top job in the prisoners’ hierarchy and was a kind of hospital manager. He reported directly to the Lagerarzt. As master of life and death, the kapo had the right to decide the fate of the hospital staff and patients. He also supervised the block seniors (Blockälteste), who were in charge of the particular hospital barracks. In turn, the block seniors had two Stubendienst (barrack orderlies), each overseeing half of the barrack (every barrack was divided into two sections), and distributing the food rations. They delegated tasks to the block servants and cleaners. The servants distributed meals as well as bread, margarine, sausage or cheese, while the cleaners scrubbed the floor twice a day, cleaned the sickrooms, the kapo’s office as well as the block leaders’ rooms; they also brought the cauldrons of food from the kitchen.

A barber was employed in each barrack to shave and do haircuts for the block senior, orderlies and patients. Patients, camp staff and all the prioners alike sported the same hairstyle—short back and sides with a clean-shaven “centre aisle” 3 cm wide running all the way down the middle of their poll.

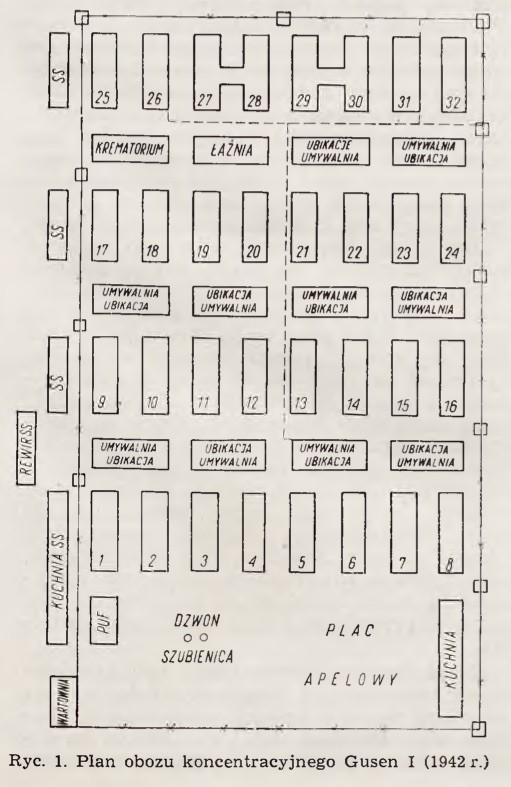

Schematic diagram of Gusen I concentration camp (1942). SS = SS barrack; rewir SS = SS hospital; krematorium = crematorium; łaźnia = bathhouse; ubikacja = latrine; umywalnia = washroom; kuchnia SS = SS kitchen; kuchnia = prisoners’ kitchen; puf = brothel; dzwon = bell; szubienica = gallows; plac apelowy = roll call square; wartownia = sentry.

The food was supplied to the hospital by the chief distributor, who brought the bread in from the storehouse and made arrangements with the kitchen manager for the quantity and type of patients’ dietary foods and extra rations.

All of the hospital’s qualified medical personnel—doctors, orderlies, dentists and dental technicians as well as lab technicians and pharmacists—were prisoners. The head of the sanitary staff was the chief physician for the prison hospital, and was under the authority of the Lagerarzt and hospital kapo.

This group of professionals was not assembled until the beginning of 1942. Initially, the hospital was located in one block, and actually it was a kind of sickroom. At this time, the kapo and Stubendienste (room services), who having no medical qualifications, did the work of physicians, making diagnoses, applying dressings and even operating as well as administering medicaments. There were a few doctors and medical students working in the hospital as servants or nurses, but they kept quiet about their medical qualifications because there was a prohibition on the employment of medical professionals—the hospital block was meant to be a venue for the selection and killing of prisoners.

The situation improved in 1942, when due to the development of the arms industry in Gusen, the Nazis changed their mind about the value of the skilled workers they needed for the armaments factories and V-1 rocket works. They started to employ doctors and medical students in the prisoners’ hospital. At this time, a surgeon was appointed head of the prisoners’ hospital, and specialist doctors were heads of the particular blocks.

A special commando, consisting of 10–20 prisoners, disposed of the corpses. But they were not subject to the authority of the hospital management.

***

In 1940–1941, the hospital was located in Block 24, which did not differ very much from the other camp barracks. It consisted of two big wards that could house about 300 patients lying next to each other on straw mattresses on the floor. In room B there was a timbered precinct called Himmelkommando (“Commando Heaven”), where the feeblest patients were put to die. They were left on their own, with no medical assistance and no food, left to die in their own excrement.

On one side of the block there were patients suffering from bloody diarrhoea, and patients with hunger oedema, phlegmons and boils on the other side. Between the two wards there was a group of rooms called the Stuben, comprising a dispensary and the residential quarters of the kapo and his assistants.

In July 1940, the hospital was extended to include two more barracks, numbered 29 and 30. Block 29 accommodated surgery, admissions, and an outpatient clinic, and Block 30 housed an internal diseases unit. Block 24 was used for patients suffering from diarrhoea. Block 27 was used as a mortuary.

Admissions, surgical outpatients, a pharmacy, a primitive physical therapy room and a laboratory were located in Stube A in Block 29. The equipment of the surgical room consisted of a field treatment table and a cabinet with a small number of surgical and dental instruments. The physical therapy room had a quartz lamp, a Sollux lamp and a Lichtkasten,2 while the laboratory had a microscope and the basic reagents.

***

The hospital was reorganised again in late 1941 after the construction of the whole camp had been completed, and could house about 20 thousand prisoners accommodated in 32 overcrowded barracks. It was given extra accommodation in Barracks 27-32, and the whole area was fenced off with barbed wire. In front of the entrance there was a precinct half the length of a barrack with a concrete floor and cold water taps installed on the outside of the building. This place was the infamous “bath,” where invalids were killed with ice-cold showers.

Block 27 was turned into a surgical unit. Half of the barrack was a recovery room with iron beds and bedclothes, for patients with injuries, the other half was intended for post-operative care. In the middle of the barrack there was a small room for nurses.

In Block 28 there was a large pathological anatomy room and a collection of anatomical exhibits and specimens. There were two adjoining rooms: a dental surgery and prosthetics lab, and a small darkroom which was used as an analytics lab. It accommodated an X-ray apparatus and physiotherapy equipment. This barrack also contained a bathroom with running hot and cold water, a pre-operative room, an operating theatre with large windows and a surgical lamp, an autoclave and surgical instruments. There were two pharmacy rooms, along with the clerk’s office, and the quarters of the kapo, Stubendienst, and his deputy.

There was a sort of wide passageway connecting Blocks 27 and 28 at their midpoint. This was where patients were admitted, but it was also the place where on several occasions poison jabs (lethal injections into the heart) were administered to large numbers of patients. Block 29 accommodated patients with internal diseases (except for those suffering from diarrhoea). Half of the block was for lung diseases, and the other half for other internal diseases. Between the patients’ rooms there was a staff residential area, and meal services, where the food supplied from the kitchen was divided into portions.

In Blocks 27 and 28, the patients had single iron beds and clean bedclothes. These blocks, surgery, and operating room were the “representational” part of the hospital, which was shown to the sanitary committees and Red Cross representatives who visited the camp from time to time.

Blocks 30 and 31 were for patients suffering from phlegmons (acute inflammation of the soft tissue) and diarrhoea. They were put in three-bunk wooden beds two or three to a bed with no bedclothes, just thin, filthy mattresses and torn, threadbare, foul-smelling blankets. As in the other hospital barracks, in between the patients’ rooms there was a staff residential area with two flush toilets.

Block 32 was located on the premises of the hospital, but it was not managed by the hospital administration. It was a barrack for invalids, where large groups of emaciated inmates known as Muselmänner were left to starve to death, waiting to be sent to the gas chamber, or put on some other kind of “transport.”

There was also a Russenrevier, a hospital for Soviet POWs, which operated in Block 16 from October 1941 to March 1942. When it was closed down, the camp staff killed 40 patients with hydrogen peroxide or petrol jabs, and gassed 164 POWs. Its doctors and hospital staff lost their jobs or were sent to other camps.

In May 1944, another sub-camp, Gusen II, was built next to the main camp. One of its barracks was turned into a hospital and two medical students and several orderlies were sent there from the main hospital, to work as doctors. Conditions in the new hospital were as bad as those in Gusen I when it was being built.

The Lagerarzt was in charge of this new hospital and the SS hospital, which was located outside the camp, close to the Jourhaus (administrative and commandant’s offices) and the entrance gate to the camp. The SS hospital employed two cleaners, a masseur and a kapo who also served as its clerk. Every day, a prisoner working as a lab technician came in from the prison hospital to collect samples for medical tests from the SS hospital.

Concentration Camp Funeral. Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click to enlarge.

Admissions

A prisoner who wanted to report for admission to the hospital had to be qualified by four officers. The first reviewer was the block clerk, who decided whether the applicant could be sent to see a doctor. His duty was to make a list of sick prisoners every evening, and he could decide not to register a prisoner without giving him a reason for the refusal. The second officer was the block senior, who called prospective patients up to the middle of the barrack and asked what their symptoms were. When he considered them trivial, he “treated” the prisoner with a few slaps in the face.

Sick prisoners who passed the preliminary hurdles had to wash, shave, and have a haircut. On the next day, when all the prisoners had gone out to their jobs, those who had been qualified as sick were ordered to stand in a line to be inspected by the commandant. Here again a good number of them were deemed not sick enough, and were immediately sent to work in the quarry, from which many never returned.

After the commandant’s inspection, the orderlies took the sick prisoners to the hospital. Before being admitted to hospital, they had to go through yet another inspection, this time by the hospital kapo. Rain or shine, winter or summer, they had to strip. The kapo was furious with any prisoner who was not clean enough. He yelled at them, beat and kicked them; many a time he killed them with a clog or anything else that was at hand; he ordered the “dirty ones” to take a cold shower using a scrubbing brush.

Only now could those who had qualified be presented to the SS doctor. They were lined up in a double row in admissions, all in their birthday suits. With the help of interpreters, the SS doctor asked the prisoners what their ailments were; sometimes he used his stethoscope to examine them. Then he decided which of them to admit and to which block to send them, and which to send for outpatient treatment.

Those admitted had to be registered, washed, dressed in hospital garments and sent to the appropriate blocks. Those rejected were sent to the invalids’ barrack, where they waited to die, be sent to another camp, or to work in one of the commandos. Those with suppurating phlegmons, minor injuries or a slightly raised temperature were sent to outpatients; they were excused from hard labour for a few days and could stay in their own barracks.

Conditions treated in the hospital

Most prisoners’ diseases were due to starvation, excessively hard labour, violence, and insanitary conditions. After a few weeks in the camp, inmates, except for a small group of kapos and Prominente (big shots), looked like a bag of bones. They began to develop oedemas and suffer from bloody diarrhoea, caused by the extremely exhausting toil and poor food rations consisting of half a litre of soup made of nettles, spinach, or swedes, 250 g of black bread and a slice of sausage or a teaspoon of curd cheese. Their legs were monstrously bloated, their scrota were red and swollen, and the tight skin was prone to infection; as a result, phlegmons could easily develop. In addition, scabies and fleas, which were widespread in the camp, caused furunculosis (boils on the skin) and made their joints and limbs swell up.

The severe emaciation was attended by psychiatric disorders such as apathy and inertia. Some prisoners started to confabulate.

The extremely hard labour in the quarries generated a lot of sick prisoners, but also the kapos and their assistants made a considerable contribution to the rising number of injuries. Every day their brutality resulted in scores of broken arms, legs, heads, wounds, and general bruises.

Prisoners with pneumonia and pleurisy, tonsillitis, pharyngitis and tuberculosis constituted another group. The tuberculosis patients were killed, especially in 1940 and 1941, by being drowned in a barrel, beaten with a hard tool, starved, “jabbed” or gassed. Starting from late 1942, they were selected for pseudo-medical experiments with a new substance called “101”; some groups were transported to Hartheim or other euthanasia centres where they were murdered en masse.

A small percentage of inmates suffered from heart diseases. Those with an impaired cardiovascular system died during interrogations or transportation in terrible conditions or of extremely hard labour.

However, the diet, i.e. starvation rations, was not conducive to the development of gastric and duodenal ulcers. There were surprisingly few cases of this disease in ordinary prisoners; more cases were observed in well-nourished functionaries. The occurrence of diseases of the liver and bile system was slightly higher; cases of cancer were sporadic.

In 1942, an epidemic of typhus and typhoid fever broke out in the camp and affected not only the prisoners but also the SS men; in both groups the death toll was high. The epidemic raged in the Soviet POW hospital as well. Infected prisoners congested all the wards, and there were plenty of them in other blocks, too. Quarantine, disinfection, and delousing did not stop the epidemic, which soon began to spread beyond the camp. During a large-scale Entläusung (delousing) campaign, SS men used cyclone B gas to kill the lice and insects—along with all the infected patients from the invalids’ barrack (Block 32) and from the Soviet POW hospital (Block 16). The hospital staff managed to save only a few patients whom they had diagnosed with non-communicable diseases and removed from the block just before the gassing began.

The day’s work in the hospital

The daily routine in the hospital and the whole camp started with the 5 a.m. bell. The walking patients got up, made their straw mattresses and beds, and went out to wash using the taps installed along the wall of the barrack, while the orderlies were busy helping the most seriously ill patients and scrubbing the floors in the wards.

In the diarrhoea blocks the orderlies had to wash the patients and dispose of the excrement and soiled mattresses and blankets. In the hospital’s first period this was done in the following way: the walking patients were ordered to take their weaker fellow inmates out of the barrack. Then all the patients gathered in front of the barrack and were hosed down with cold water. Many did not survive those ice-cold showers. Those who endured this morning “toilet” trudged back to their dosses.

Breakfast was served around 6 a.m.: half a litre of coffee made of ground cereals or Sonderkost—“special food,” soup thickened with flour. Meanwhile, the hospital clerks inspected the wards, examining patients and recording the deaths.

The roll call was held at 6:30 a.m. A Blockführer, kapo, and chief clerk went round the wards and counted the bedridden patients, who were ordered to have their arms by their side. During the inspection all the hospital staff stood at attention in a double row.

After the roll call, the doctors began their activities: examining patients, applying plaster casts and performing surgeries. The orderlies distributed medicaments, made dressings using paper or rarely muslin bandages and bands, and administered various medical treatments. The hospital dispensary was equipped with a sufficient amount of different types of ointment and medications.

After the morning admissions, the SS doctor and prisoner-doctors performed surgeries in the operating theatre. Alternatively, he would visit other hospital blocks to examine patients and decide about their fate.

The laboratory, pharmacy and dental surgeries opened at 7 o’clock. From 7 to 8 patients with gastrointestinal problems had X-rays done, and chest X-rays were done after a break from 12 noon to 1 o’clock for the midday meal. A portable X-ray device was used for bedridden patients. In the afternoon and evening after roll call the lab served as a physiotherapy room, dispensing diathermy, quartz lamp, Sollux lamps, and Lichtkasten treatments to in- and outpatients.

After the patients’ midday meal, which consisted of one-third of a litre of soup, the staff did the same duties as in the morning. At 5 o’clock (or at 6 in summer) there was an evening roll call followed by supper, which consisted of one-third of a kilo of bread, a smattering of curd cheese, marmalade or margarine, a thin slice of sausage, and half a litre of unsweetened black coffee; diarrhoea patients got half of litre of soup thickened with flour.

Lights-out for the hospital was at 8 p.m.

SS physicians and kapos3

In the course of Gusen’s operations, about a dozen SS officers served as its prison hospital’s Lagerarzt (chief SS physician). Some supervised the hospital for a few weeks, others for several months or more. Each of them will be remembered for his characteristic way of treating patients. Some were feared as monsters, others behaved like human beings. All of them were accountable to the Lagerarzt of Mauthausen main camp and had to obey his orders. However, they carried out his instructions in very different ways.

The founder of Gusen’s prison hospital was SS-Standortarzt Dr Richard Krieger, chief physician of Mauthausen, who only made an occasional appearance in the new sub-camp, making Kapo Franz Zach and Blockführer Heinrich Roth responsible for all the medical duties and carrying out his orders in Gusen. Krieger was the first to order the use of phenol jabs to kill patients. His order was carried out by Zach and Roth on 12 victims.

Krieger’s successor was Dr Fritz Schildbach, a habitual drunkard and rascal who specialised in hernia operations, and thereafter Dr Eduard Krebsbach, who was the chief physician of the Mauthausen camp hospital until its closure and managed Gusen prison hospital through a number of deputies, ordering all the mass killings in both camps, including a selection of 2,000 prisoners and sending them to the Hartheim euthanasia centre, where they were murdered in the Aktion H-13 operation. Every time Krebsbach appeared in Gusen prison hospital, it meant that a large number of patients would be gassed or sent to a death centre.

The first physician to run Gusen prison hospital independently was SS-Hauptsturmführer Sigbert Ramsauer, albeit he had to report to Dr Krebsbach. The son of an Austrian supreme judge, Ramsauer earned notoriety by ordering the killing of prisoners with distinctive tattoos; their tattooed skin was processed, tanned, and used to make handbags, bookbindings, lampshades, etc. Ramsauer carried out pseudo-medical experiments on prisoners, including healthy ones.

His successor, Dr Erwin Heschl from Vienna, performed similar experiments. He was interested in gynaecology, although he claimed to be a heart disease specialist.

The third pseudo-experimental scientist and physician was Dr Hermann Richter, infamous for “joining up the small and large intestine.” He operated on healthy prisoners. Following his pseudo-experiments, prisoners either died or became invalids and were sent to their deaths. Richter liked to take photos of the particular phases of his surgeries.

Drs Josef Jung and Erich von dem Hoff, a dentist, also had bad reputations, but the worst of all the hospital physicians was SS-Hauptsturmführer Hermann Kiesewetter, a slim, fair-haired man of medium height, aged about 28. He was appointed camp physician of Gusen in 1942 and it was during his term of office that most of the mass murders took place. He turned a blind eye to the abuses in the hospital and encouraged kapos Roth, Zach, and Kassandra to kill patients. In fact, he hated all the prisoners, especially the Poles, considering them criminals and enemies of Nazi Germany. Regularly drunk, he used to pay unexpected visits to the camp; he took those he came across on the way to the hospital block to operate on them. Many a time he did not complete the surgery, leaving the victim under anaesthesia with an open abdominal cavity and bowels drawn out. He conducted admissions while drunk, qualifying newly admitted patients for jabs or transferring them to the invalids’ block, which meant sending them to Hartheim, the infamous euthanasia centre and its gas chambers and experimental institute. He ordered and supervised 70 cyanide killings in Block 26, had the camps “disinfected” during a typhoid epidemic, gassed the typhus patients from Blocks 16 and 32, and sent many prisoners to their deaths by having them hosed down with ice-cold water.

Kiesewetter’s successors, Drs Schildbach and Eberhard Haas, were not remembered for any special deeds. In 1943, when SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr Karl Böhmichen was head of the hospital, there was no mass extermination of tuberculosis patients. They were put in the left wing of Block 29 and tests with a new medicament, “No. 101,” were done on them: a tablespoon of small red granules of it was administered to them three times a day. After a few days, patients started to suffer from nausea, vomiting, and headaches.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr Benno Adolf, a Wehrmacht officer in the rank of captain, was camp physician for three months in 1944. He had fought and was wounded in the Battle of Stalingrad, taken to hospital and left the Eastern Front. On recovering, he was assigned to Gusen for convalescence. There were no killings in the hospital during his term of office. He put a ban on extermination, “jabbing” and gassing patients, and refused to send invalids out of the camp. He managed to secure bigger food rations for patients and extra food for convalescents. He spent all his free time in the hospital and made friends with the doctors and staff. During meetings in the lab he often shared his own experiences, describing the horrors of the war and the situation of the German troops at Stalingrad. He also predicted the imminent fall of Nazism and encouraged, comforted, and helped the inmates. Since Dr Adolf had frequent and violent arguments with the camp commandant and the SS-men, standing up against the abuses, segregation, and violence against prisoners, it was not surprising that after a few months he was declared not fit to run the hospital and sent back to the front.

After his departure, SS-Hauptsturmführer Helmuth Vetter restored the ancien régime of the hospital’s first years. He hated the prisoners and did his damnedest to them. He disliked the hospital staff, and was always emphasizing his superiority. He and other SS-men left Gusen a few days before it was liberated.

The first hospital kapo was Franz Zach, whose assistants were Blockführer Heinrich Roth and Stubendienst Karl Kofferbeck. These three criminals and butchers ruled the hospital with an iron rod, “treating” patients and terrorising patients and other prisoners alike. Before the war, they had been serving long prison sentences for assault and other criminal offences; and when given absolute power in the camp and encouraged to kill prisoners who were apparently “political criminals” accused of starting the war and murdering defenceless German citizens. Now the three monsters could give vent to their instincts and flaunt their proficiency as killers.

Depending on their mood and the circumstances, they used all sorts of methods to murder inmates selected for death. Their usual methods were to beat victims to death with a stool or clog, or drown them in a bucket or barrel of water. They starved those with bloody diarrhoea to death, which they considered a kind of diet and the right treatment; or they hosed them down with ice-cold water to wash the excrement off them. Of course, the “medical treatment” they dispensed was not effective at all (in the medical sense). At night Zach and his companions indulged in drunken orgies, during which Zach made a show of his sexual prowess.

One night their yelling was so loud that it was heard in the SS barracks and infuriated Zach’s superiors. He was dismissed and sent to a penal commando. However, after a few months, when the Soviet POW camp was set up, he was back again, appointed kapo of the Russian hospital. There he applied his “best practices.” He took a part in the mass jabbing and gassed all the inmates of Block 16. The prisoners’ underground resistance movement in the camp sentenced him to death and carried out the sentence in 1943, though the cause of his death given officially was tuberculosis.

Zach was succeeded by Heinrich Roth, whose exploits surpassed those of his predecessor, and he went down in the history of the camp and in the memory of prisoners as “The Red Phantom.” With a face looking like a pug’s muzzle, and pale blue, bulging eyes showing tell-tale signs of the last stage of syphilis, Roth revelled in inventing and using newer and newer methods of killing. Each of his outbreaks of fury bordered on insanity. Every day he butchered several prisoners. None of the hospital staff, nor even his colleagues dared to raise any objections, fearing his reaction. He ruled the hospital for several months. In January 1942, one of the SS doctors who had been warned that Roth might attack him, killed him with a dose of cyanide injected intravenously.

Thereafter the office of hospital kapo went to Josef Bobrowski, a Volksdeutsche from the Poznań region who had worked as an orderly in Jarocin hospital before the war. In the camp he was nicknamed “Kassandra.” He was first employed as a cleaner and then as an orderly. In the initial phase of his term in office he was quiet and friendly and listened to the advice and tips of Dr Gościński, ex-head of Jarocin hospital and Bobrowski’s former boss. But things changed when Kassandra became the immediate superior not only of the chief physician but of the entire hospital staff as well.

After some time, absolute power, being flattered by his companions and the fear of losing his privileged position made Bobrowski adopt and follow his predecessors’ conduct regarding patients. Despite Dr Gościński’s objections, he began treating patients, making diagnoses, prescribing treatment, and even selecting those whom he considered incurable and sending them to their deaths. He took part in jabbing procedures and sent 70 patients from Block 27 to the gas chamber. His response to warnings from doctors and colleagues was to regard them as enemies and take every opportunity to harass them. In the end, he threatened that he would inform the SS men of the inmates’ secret resistance movement in the hospital, as he did not want to lay his head on the block for anyone.

Consequently, Bobrowski had to be eliminated, as he had tarnished the honour and dignity of a political prisoner and betrayed the patients’ hopes, but most importantly, his threats posed a great danger for the underground resistance movement. The camp authorities heard that Bobrowski had been trafficking in drugs and alcohol stolen from the hospital, which he had exchanged for cigarettes and gold. With an SS interrogation and dismissal looming over him, and fearing being sent to the penal commando and work in the quarry, the over-ambitious Kassandra committed suicide by taking cyanide.

The last hospital kapo was Emil Zommer, a Sudeten German who regarded himself a Czech, and in fact spoke fluent Czech. He had been arrested for belonging to a communist organisation. In the camp he had various jobs. When he was hospital kapo, he was friendly towards the inmates, treating them fairly and standing up against violence in the hospital and camp. Moreover, he was involved in the inmates’ resistance movement, especially in the group collaborating with the Czech and German prisoners.

Medical staff

Undoubtedly, the most interesting and prominent individual among the prisoner-doctors was the surgeon Dr Antoni “Toni” Gościński, chief physician of the prison hospital. He happened to start working in the hospital by sheer chance. In a desperate attempt to take his life after being beaten up and having his right arm broken, he was walking straight for the barbed wire. But on his way, a fellow prisoner who worked in the camp hospital stopped and took him to the dispensary, treated the fracture, gave him some food and managed to register him as a patient. After recovering, Toni became an unofficial adviser to the hospital kapo and SS physician, and was subsequently appointed chief physician and hospital surgeon.

His self-sacrificing service and dedication to the needs of the sick went down in the history of the camp and are cherished memories for numerous prisoners thankful to him for helping them survive the worst period of their lives. Having earned the respect and trust of the SS personnel and doctors, he tried to deter them from implementing their brutal methods. He was also one of the main organisers of the resistance movement in the camp.

Another remarkable figure was Dr Feliks Kamiński, formerly a lecturer in descriptive and pathological anatomy at Poznań University. Having survived the ordeal of the penal commando and hard labour in the quarry, he was sent to work in the hospital early in 1942. He was commissioned to take over the management of the pathological anatomy department and create a museum of anatomical specimens.

He performed post-mortems on deceased patients and prepared anatomical specimens, some of which were sent to medical centres in Germany. Dr Kamiński’s assistants were Stefan Malost, a medical student from Kraków, an expert in histopathological techniques; Edmund Wierzchowski, a prosecutor by profession; and Piotr Pawłowski, who held a master’s degree in pharmacy. They handled all the arrangements. Dr Kamiński and his assistants all belonged to the underground resistance movement in the camp, so the post-mortem room was often used for secret meetings and discussions.

In his leisure time Dr Kamiński pursued his hobbies, music and painting. He was in touch with many prisoners who did various jobs in the camp, and did his best to help them, especially the musicians, painters, and scientists. Many of them owed their lives to him.

I should also mention two internal medicine specialists, Drs Józef Markiewicz and Adam Konieczny, who played a vital role in the history of the camp hospital. Both were excellent doctors, courageous members of the underground, and simply good friends. Every day they risked their lives treating patients, keeping double records of their illnesses, and ignoring the SS doctors’ medical recommendations. Both the patients and hospital staff respected them and appreciated their help. Markiewicz and Konieczny contributed to the organisation of the resistance movement and were very actively involved. On 24 April 1945, just a few weeks before liberation, Dr Konieczny had a nervous breakdown and took an overdose of drugs because he could not bear the pressure of camp life any longer. His death was a shock for all his friends and inmates; their farewell and tribute to him was a silent manifestation of the inmates’ solidarity. Dr Markiewicz was transferred to another camp.

Mieczysław Lisiecki, a medical student from Poznań, and Józef Sabuda from Silesia, who had just finished grammar school, worked as paramedics under the supervision of Drs Markiewicz and Konieczny. They and other doctors and nursing staff developed their professional medical skills, attending the clandestine courses run by prisoners who were specialists in a variety of disciplines. They learned various methods of treatment and followed their fellow doctors’ recommendations.

Another group of doctors, Czeslaw Budny, Kazimierz Miłoszewski, Jan Krakowski, Leon Królak, and the sanitary assistants of Block 30 and Block 31, worked miracles, applying their courage and ingenuity to treat severe diseases with the primitive means they had available. All of them followed the orders of the resistance group operating in the hospital. It needs to be said that they fulfilled the hopes and expectations made of them, helping to improve conditions in the camp and save lives.

Marian Filipiak, a medical student from Poznań, was one of the most respected and appreciated individuals in the camp. Initially, he worked in the internal section, and later in the operating theatre as chief assistant to Toni, Prof. Podlaha, or the SS doctor who happened to be operating. He was fully committed to the resistance movement in the hospital and often risked his life for the sake of the hospital community. He was also one of the few who stayed in the camp after its liberation to attend to patients; later he cared for them during their transportation to Poland.

I cannot enumerate all the merits of the hospital staff who cared for the suffering and weak with profound dedication. Let me mention at least some of their names: Eugeniusz Pięta-Połomski, Bernard Drahaim, Feliks Mocny, Tadeusz Twardzik, Leon Zynda, Wladyslaw Cybulski, Jan Zblewski, Wiktor Gospodarczyk, Alojzy Młodyszewski, Zygfryd Mielcarewicz, Franciszek Zieliński, and Staś Tasarek.

Beside the people who were committed to their work in the hospital, there were also sinister characters, common criminals and villains, notorious for their violence and extreme sadism, just like Zach and Roth.

The worst was Karl Kofferbeck, initially Stubendienst of Block 24 when Zach and Roth were hospital kapos. Later he was block senior of the Soviet POW hospital and finally block senior of Block 31. He had been convicted of multiple murder. Kofferbeck was a giant with pale blue eyes and an insensitive look on his face, and he moved like a gorilla. In a word, he was the epitome of evil. He was involved in every murder committed in the hospital. Moreover, he ignored all the reprimands given him by the doctors, inmates, and staff. He died of TB at the beginning of 1944.

The hospital’s cultural and social life

Almost all the hospital staff considered themselves a close and well-knit family. They realised that their specific working conditions obliged them to carry out their duties as conscientiously as possible. They all knew that their chances of survival were slim.

To keep themselves from succumbing to despair and loss of hope, they created a programme of social, cultural, and scholarly events—just as the inmates in the rest of the camp did. Almost everyone started learning foreign languages, primarily Russian, Spanish, and English. The prisoner-doctors conducted training courses for medical students and paramedics. In fact, they managed to implement a university syllabus, covering almost all the specialist fields of medicine.

Dr Kamiński lectured on descriptive and pathological anatomy, Prof. Franciszek Adamanis gave physiological chemistry and pharmacology lectures, Dr Gościński lectured on surgery and gynaecology, Dr Konieczny and Dr Markiewicz gave lectures on internal medicine and infectious diseases, and Dr Budny lectured on dermatology. They did their best to pass their knowledge and experience on to their “students,” who took in all the theory, trying to put it into practice in the hospital dispensary, wards, and treatment rooms.

The hospital staff established a network of contacts and working relations with prisoners distinguished in their field—scholars, including eminent personalities; poets, painters and musicians, and did all they could to help them. In return, these persons were happy to share their artistic work, giving concerts for the patients, organising literary soirées, or lecturing on a variety of subjects.

Poets Grzegorz Timofiejew, Zdzisław Wróblewski, Konstanty Ćwierk, Włodzimierz Wnuk, and composer Gracjan Guziński gave poetry readings and music recitals to an enthusiastic audience—the patients. Such events invigorated and helped them to persevere and survive the camp, bolstering their confidence that they would recover their freedom. There were also choral performances given outside the hospital block by a number of prisoners’ choirs conducted by the distinguished musicologist Lubomir Szopiński. Stanisław Grzesiuk’s group of vocalists sang to cheer up the bedridden patients. Organist Józef Pawlak and violinist Heinrich Lutterbach gave solo recitals, and composer Gracjan Guzinski conducted a large camp orchestra. Other vocalists and actors who gave frequent performances included Tadeusz Faliszewski, Wacław Gaziński, Zygmunt Malinowski, and Witold Jelenski, as well as some Spanish, Italian and French prisoners whose names I cannot remember.

There were also painters and sculptors who managed to create their works in secret—for instance, there was Prof. Aldo Carpi of the Brera Academy in Milan, Zbyszek Filarski, Gutkowski, Mieczysław Lando, Maksymilian Chmielewski, Nikiel, and Nowicki. The staff managed to save Henryk Kołodziejczyk, the only prisoner to survive the winter “invalid bath.” He was put in Block 30, where he could make his models of vintage corvettes.

Many of the doctors and hospital staff were talented artists. Dr Kamiński painted and played the zither, Stefan Malost and Dr Gościński played the violin, and I sculpted. Some tried to develop their vocal skills.

The monotony of our camp life was interrupted by the arrival of women of different nationalities, prisoners from Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, who agreed to work as prostitutes in an all-male camp in return for a promise to be released. Almost all the Polish prisoners and the majority of the other inmates boycotted this newly created institution, located in a sturdy, purpose-built house. However, the block seniors, kapos, clerks, and other big fish enjoyed patronising the brothel. Earlier they had indulged in mass killing and perverse orgies; now they turned their affections to those ten women locked up in the brothel, rivalling one another in courtesy and showing off their masculine virtues.

Every week the girls were brought into the hospital and Dr Gościński had to examine them for VD, and I had to do the lab tests. So I had the opportunity to learn something about their predicament. Most of those women were Germans arrested for vagrancy or “insubordination to the German Nation.” There were a few Frenchwomen and one Polish woman. All of them had been promised that after three months of service in the camp (ten customers a day) they would be set free. As it turned out, after three months they were killed and replaced by another group of girls.

The resistance movement and its activities in the hospital

The idea to organise resistance against the terror, killing, and abuses in the camp and hospital was first put forward on 23 December 1941. That evening numerous invalids and severely ill patients were killed. Their yells could be heard all over the camp. At that moment the three of us (Toni Gościński, Mariusz Filipiak and I) met in the laboratory and resolved to do something about the terror. We pledged to put up resistance to the perpetual acts of genocide and lawlessness, and concluded that our first task would be to improve relations in the hospital and make the patients feel secure by providing them with as much care as we could. We also pledged to counter SS attempts to kill our patients. To begin with, we intended to get rid of Zach and Roth. Next, we wanted to use all our contacts to bring as many doctors and medical students as possible into the hospital. The first inmates who were informed of our plans were Pięta, Drahaim, Mocny, Twardzik, and Zynda. We held our meetings in the lab, where we had an easy alibi in case of questions—we were waiting there to carry out medical examinations or for test results.

When Kapo Roth died in 1942 and was replaced by Kassandra Bobrowski, and a large number of medical students were sent to work in the hospital, our scheme could expand. The Polish doctors (Kamiński, Markiewicz, Konieczny, Budny) and orderlies joined us. We also involved Prof. Adamanis, Prof. Podlaha, Gruber, Pablo del Rio and M. Kushayev in the inmates’ underground resistance movement. We discussed how to save TB and “incurable” patients, and decided to keep a double set of medical records and to recommend the seriously ill for treatment in the hospital blocks.

Although many of the big fish, kapos and Vorarbeiter (foremen) noticed the shortcomings of the hospital staff in the performance of their duties, they preferred to live in peace with us, in case they were denied medical care if they got sick. They all remembered the deaths of Zach, Roth, and Kofferbeck. Also, they knew that Van Losen and Bocker were seriously ill and that a few brutal kapos in charge of the work in the quarries had died of typhus. So the functionaries wanted to have the medics on their side as friends, not as enemies. In addition, sometimes they could count on getting pills or injections to enhance their strength and potency, or on getting their rheumatism treated under the lamps. They could even wangle some alcohol or meths, which was considered as good as vodka.

We exploited this close interaction in various operations. For example, we struck a deal with the kapos and staff of the prison and SS kitchens, and the managers of the food warehouses and the SS officers’ mess, with the result that the hospital began receiving more food, bread, and extras; the quality of the cooked meals improved. Cybulski, the chief food administrator, was particularly clever at “organising” and delivering food to the patients.

Our efforts to provide food, protect prisoners at work, and get less strenuous jobs for those inmates who needed them, especially for young prisoners, proved successful. A kapo who wanted some benefits from the hospital staff did not dare to use violence against a prisoner who was our “protégé”; on the contrary, he gave him a better job or turned a blind eye to misdemeanours. Block seniors usually refrained from exercising their power over those prisoners we wanted to protect. Some cooks, the staff working in the officers’ mess, the SS canteen and food warehouses, as well as the Stubendienste even provided extra rations for groups of prisoners recommended by the doctors or orderlies. The hospital personnel tried to use their contacts first of all to help the convalescents whose health could deteriorate again due to malnutrition and extremely hard labour, and those inmates who “deserved” special support or were completely helpless in the terrible camp conditions.

Naturally, we, hospital conspirators, collaborated with the resistance group operating in the other barracks. When large groups of prisoners of other nationalities, chiefly Russians, Yugoslavs, Hungarians, and Italians, started to arrive in the camp and were put in quarantine, we worked with the resistance movement in the rest of the camp to help them by providing medications, food and other kinds of support. Whenever we could, we helped to assign them better jobs. Thanks to that, a large number of army officers, scientists, engineers, and other prisoners avoided immediate death and subsequently they could help their fellow countrymen. They gradually adjusted to the conditions in the camp and were assigned better jobs, so they, too, began organising resistance groups in their communities. In this way, the underground network covered prisoners of all the nationalities confined in the camp.

Prisoners worked in the SS barracks and the secretariats located outside the camp, and were in touch with local people, so the resistance movement expanded significantly. Inmates had access to the latest news from the fronts. In turn, they could pass on information to the outside world of the violence and mass murders committed in the camp.

Liberation and the closure of the hospital

The imminent liberation was heralded by the withdrawal, or more precisely getaway, of the SS camp authorities and guards. The camp was left under the control of the ancillary police. The inmates breathed a sigh of relief because they knew the SS had been planning to exterminate all of them.

They were to be exterminated during an alert for everyone to go down into the tunnels and passages in the quarries, in which everything was ready for the gas to be let in. The chief SS physician issued an ordinance for the alert, establishing the order in which the patients were to be transported to the quarry. No one would be allowed to remain in the hospital during the alert.

The prisoners decided not to give in too easily. They had made detailed maps of the tunnels and placed stolen sticks of dynamite in a few places in the quarry. They had also collected weapons, while the laboratory staff, supervised by Prof. Adamanis, had started to produce explosives from the chemicals available to them. These explosives were distributed to inmates in the know, who were to perform the sabotage. Fortunately, the SS plan failed.

Although the spectre of mass extermination vanished when the SS made their escape, the prisoners were now confronted with the threat of hunger. The fleeing SS had looted the camp warehouses, and the new guards could not cope with managing and maintaining order in the camp. In this situation, the secret hospital bunkers with a secret cache of food were opened.

Now the hospital was supervised only by the prisoner-doctors and sanitary assistants, since the SS chief physician and most of the functionaries had fled.

At night, excited prisoners watched the lights flashing over the camp and kept their ears open for the detonations coming from the approaching front. They awaited the longed-for liberation.

At 4.30 p.m. on May 5, a sudden confusion overwhelmed the prisoners gathered in the roll call square. But soon cries of joy and cheering could be heard; thousands were singing the Polish national anthem. The patients and hospital staff realised that liberation had come. But as the shouting intensified, it was evident to those in the hospital that the hated oppressors were being lynched. After a few moments, we saw the camp’s chief clerk Jahnke running for the hospital gate, chased by a crowd of prisoners. Before he managed to take shelter in a safe hideout, he was killed and literally pulled to pieces by the raging mob. A similar fate befell 34 block seniors, kapos and other functionaries, all of them hated oppressors.

All the hospital personnel were now free to walk about the camp without fearing anyone. It was the greatest sign of respect that the prisoners could give those who had cared for them.

Still on the same day, some of the patients who felt strong enough to walk and several members of the hospital staff left the camp. Those of the carers who stayed in the camp continued to look after the severely ill patients until they were handed over to the American evacuation hospital.

The Americans moved our hospital to the SS barracks. They set up surgical, internal medicine, diarrhoea, and pulmonary diseases wards, and a convalescents’ section. The head of the hospital was Captain R. Austin, and the chief internist was Captain S. Smith. Both of them as well as all the hospital personnel were very kind to the patients and made every effort to help them recover as soon as possible.

Dr Gościński and several doctors and orderlies went to nearby Linz on commission from the Red Cross to organise a new hospital for the survivors. The rest of the medical personnel were issued with khaki uniforms and worked in the hospital under the supervision of American doctors. They were all treated as friends and colleagues, and the only thing that distinguished them from the American officers was the red stripe on their sleeves with the inscription Poland.

After a few weeks of treatment, the patients were transferred to Mauthausen, from where they could go back home. The American evacuation hospital was closed and moved to carry out its mission in other places, and the story of Gusen prison hospital finally came to an end.

Translated from original article: Wlazłowski, Z., “Szpital w obozie koncentracyjnym w Gusen,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim; 1967.

Notes

- This article is an excerpt from a larger study in Polish on Mauthausen-Gusen.

- Lichtkasten—a chest fitted with light bulbs; a patient sat inside the chest and was given an electromagnetic radiation treatment from the light coming from the light bulbs.

- In this sub-chapter we have put in first names and corrected misspelled surnames. Presumably Dr Wlazlowski cited these names from memory, but did not have the opportunity to see them in written documents.

All notes come from Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

- Bellak, Giorgina, and Melodia, Giovanni. Donne e bambini nei lager nazisti. Milano: Associazione Nationale ex Deportati Politici nei Campi Nazisti; 1961.

- Bernard-Aldebert de, Joseph. Chemin de croix en 50 stations. De Compiégne a Gusen II en passant par Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Gusen I. Paris: Arthéme Fayard; 1946: 112.

- Bielecki, Wacław. Obozy śmierci. Moskwa: Związek Patriotów Polskich; 1944.

- De Boüard, Michel. Gusen. Revue d’histoire de la Deuxiéme Guerre mondiale. 1962; 45: 45–70.

- Cinca Vendrell, Amadeo. Mauthausen-Gusen 1940-1945. Lo que Dante no pudo imaginar. Saint-Girons: Descoins; 1946.

- Generowicz, Zbigniew. Prawda oskarża Niemcy hitlerowskie (3 lata obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Gusen). Poznań: Księgarnia Wydawnicza; 1945.

- Gostner, Erwin. 1000 Tage im KZ. Ein Erlebnisbericht aus dem Konzentrationslagern Dachau, Mauthausen und Gusen. Mannheim: W. Burger; 1946.

- Grzesiuk, Stanisław. Pięć lat kacetu. Warszawa: Ksiązka i Wiedza; 1962.

- Habrina, Rajmund. Gusenský pochod. Brno: GBS; 1945.

- Heim, Roger. La sombre route: souvenirs des camps d’extermination Allemand. Paris: José Corti; 1947.

- Jednodniówka wydana w 16-letnią rocznicę oswobodzenia hitlerowskich obozów koncentracyjnych Mauthausen-Gusen z okazji 8. kolezeńskiego spotkania w Bielsku-Bialej. Bielsko-Biala: Bielski Zakład Szop.; 1961.

- Jégo, Jean-Baptiste. L’enfer de Gusen. Chapître complémentaire é la vie de Marcel Callo. Rennes: H. Riou-Reuzé; 1948.

- Junosza-Dabrowski, Wiktor. Podróż przez piekło. Paryż: Elka; 1946.

- Liggeri, Paolo. Triangolo rosso. Dalle carceri di S. Vittore ai campi di concentramento e di eliminazione di Fossoli, Bolzano, Mauthausen, Gusen, Dachau. Marzo 1944 – Maggio 1945. Varese: Del Rovo; 1953.

- Liste officielle n°1 des décédés au camp de Mauthausen et kommandos. Paris: Bureau Nationale des Recherches (n.d.).

- Myczkowski, Adam. Poprzez Dachau do Mauthausen-Gusen. Kraków: Księgarnia S. Kamińskiego; 1946.

- Nogaj, Stanisław. Gusen. Pamiętnik dziennikarza, I–III. Katowice: Komitet Byłych Więźniów Obozów Koncentracyjnych Gusen; 1945.

- Ostrowski, Tadeusz. Więźniowie, czapki zdjąć! Pamiętnik dziennikarza z pobytu w obozach koncentracyjnych. Kraków: Czytelnik; 1945.

- Osuchowski, Jerzy. Gusen, przedsionek piekła. Warszawa: MON; 1961.

- Proudfoot, Malcolm J. European Refugees 1939–1952. A Study in Forced Population Movement. London: Faber and Faber; 1952.

- Sébille, René. Sans craintes ni murmures. Paris: Editions Du Myrte; 1945.

- Timofiejew, Grzegorz. Wysoki plomień. Wiersze z konspiracji i obozu. No place of publication: Książka; 1946.

- Wantula, Andrzej. Z doliny cienia śmierci. London. No publisher or publication date given.

- Wlazłowski, Zbigniew. Szpital Revier w niemieckim obozie koncentracyjnym w Gusen. Lata 1940–1945. Illustrated edition of the weekly Glos Wielkopolski. Poznań; 1947.

- Wnuk, Wlodzimierz. Obóz kwarantanny. Wspomnienia z Sachsenhausen. Kraków, Księgarnia S. Kamiński; 1945.

- Wnuk, Wlodzimierz. Byłem z Wami. Warszawa: Pax; 1960.

- Zalachowski, Feliks. Gusen — obóz śmierci. Poznań: Związek Byłych Więźniów Politycznych; 1946.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.