Author

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English.

During epidemics of typhus in Auschwitz many prisoners were observed to fall into a profound state of anxiety verging on panic; so overwhelming was their dread of contracting the disease that they were disheartened and their immune system seemed to be diminished. Survivors remember numerous cases of complications and deaths of typhus patients who were sure that if they caught the disease they would not survive. One of the victims of this condition was Dr Zofia Kączkowska, a prisoner-doctor who rendered distinguished service in the prisoners’ hospital at Birkenau.

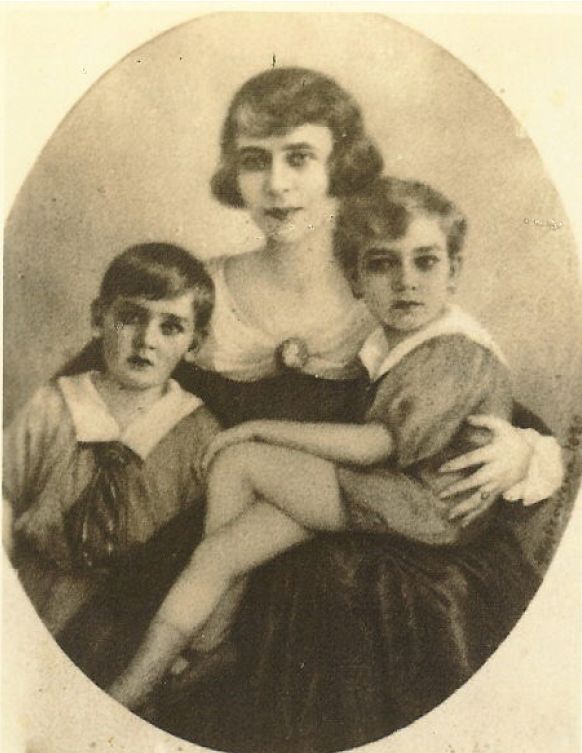

Zofia Kączkowska with her sons: Jan and Zbigniew. Source: Ciesielska, M. Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau, Warsaw 2015.

Zofia Kączkowska née Kraeutler was born on 16 April 1893 in Kraków. She went up to the Jagiellonian University, Kraków, to read Medicine, and continued her studies at Charles University, Prague, graduating in October 1918 with a Doctor Medicinae Universae degree.1 In 1920 she married Leszek Kączkowski, a mechanical engineer. She was an assistant physician to Prof. Aleksander Rosner, head of the Jagiellonian University Gynaecology and Obstetrics Clinic. Zofia and Leszek had two sons, Zbigniew and Jan. After a few years in Królewska Huta (now Chorzów) and Bydgoszcz, the family moved to the new port of Gdynia.2

In Gdynia Dr Kączkowska took up an appointment as a school physician. She was a self-sacrificing and hard-working doctor and social activist, full of care and concern for her young patients, with an enthusiastic sense of duty, and profoundly patriotic. She supplemented her formal duties with talks on hygiene and educational matters for the pupils of her school and their parents. She took an active part in the scouts’ and guides’ movement, attending a number of camps and jamborees.

Dr Kączkowska ran sanitary training courses for PWK, a women’s military training organisation. For many years she was the secretary of Towarzystwo Szkoły Średniej w Gdyni (the Gdynia Secondary School Association). She was a modest, truly caring person, characterised by a kind-hearted dignity. She loved poetry, especially the works of the Polish Romantics and the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) poets, and liked to recite many of the poems of Mickiewicz, Wyspiański, Kasprowicz, Przerwa-Tetmajer and other Polish poets off by heart.

Zofia Kączkowska had a personal charm that made people like her. Her home was a venue for social occasions attended by scholars and artists; her regular guests included celebrities like Professor Michał Siedlecki3 and his son Stanisław, travellers distinguished explorers, the Cracovian sculptor Jan Raszka4 Dr Wanda Czerwińska née Bobkowska,5 and many others.

When the War broke out, Dr Kączkowska was in Gdynia, working as a physician in the municipal hospital on plac Kaszubski, and attending to wounded soldiers and civilians during the combat that occurred in the Polish coastal region. When the Nazi Germans occupied Gdynia, they started their “resettlement” (deportation) plan for the local Polish population. Zofia Kączkowska put her own life at risk to help people who were being deported in large numbers, illicitly providing them with food, medicines, and clothing for the journey. She spent many days out of doors comforting people who had been evicted from their homes and were sleeping out on skwer Kościuszki, and narrowly missed being resettled herself, only because as a doctor she was still needed by the Polish inhabitants who were still in the city. She was allowed to leave Gdynia in late October 1939, when the resettlement programme was drawing to a close. In March 1940, after staying a few months in a small place called Orenice near Piątek (Central Poland), the family moved to Warsaw, and Zofia took a job as a doctor.

In June 1941 Zofia and her son Zbigniew, who was using the false name “Kaczanowski”, moved to the Biała Góra region of Powiat of Kozienice. The area was full of underground resistance men and their activities, so again Zofia was helping the sick and wounded in danger of being caught by the Germans. One of her patients was a wounded Russian resistance fighter who had gone into hiding in a neighbouring village.

At dawn on Sunday, 11 April 1943, the Kączkowski family found themselves trapped by thousands of Germans on a manhunt for resistance men. A total of about four thousand Gestapo and SS men, Bahnschutz, blue police and other units were taking part in a gigantic round-up, under the command of Fuchs,6 the chief of the Gestapo unit stationed in Radom. The resistance men managed to get away (except for one wounded man), but over a hundred local people, including a few who were members of the AK,7 were arrested. At a farm called Marynki in the locality the Germans discovered a weapons cache of 17 guns and ammunition.

Zofia and Zbigniew were put on a train and taken to Radom jail. On the way they managed to speak to each other and agree on what they would say in the interrogations that were ahead of them. Dr Kączkowska was arrested under her real name, but her son was arrested as Kaczanowski. However, the Germans knew they were related, so they were both beaten up already during their first interrogation. The investigation continued until 24 June 1943. On that day in the morning lorries were waiting to take them to Radom railway station. Prisoners were told to leave their cells, had their coats returned to them, and their hands were tied behind their back. At the station they were made to board a freight train, a hundred in a carriage, and the doors of all the carriages were locked and bolted. The train set off, and in the late evening arrived on the ramp of Birkenau.

As they alighted from the train, the prisoners were given a welcome by SS men yelling at them, hitting them with whips and rifle butts, and terrorising them with growling dogs. Zbigniew managed to glimpse his mother standing in a row of five in a column of prisoners. She had arrived on the same train from Radom. Incidentally, page 11 of the Polish version of Danuta Czech’s Auschwitz Chronicle8 says that the 94 women prisoners (Numbers 46431–46524) who arrived on this train had travelled from Kraków, and the same erroneous information is in a letter dated 29 February 1969 from the Red Cross International Tracing Service at Bad Arolsen to Zbigniew Kączkowski.

At Birkenau Dr Kączkowska was registered as No. 46442 and soon after arriving was sent to work as a prisoner-doctor in Birkenau prisoners’ hospital. She had to work on Block 22, which accommodated German women prisoners who were sick. She often said she regretted she was not looking after her compatriots, but cheered herself up by saying that the German hospital block was “more decent,” better equipped and not so congested, the hygiene was better and it was not so lice-ridden, so she’d be less likely to catch typhus.

Dr Kączkowska lived in Block 23 with the other Polish women prisoner-doctors, and was a tremendous companion. Survivor Dr Irena Białówna recalls that she was cheerful, loved to sing and recite poetry, and was optimistic that the war would soon end. She tried to get girls in the hospital blocks to hold soirée entertainments after the evening roll call. She conjured up a pleasant, family atmosphere at the prisoners’ get-together for Christmas Eve9 1943. She entertained them singing Polish Christmas carols and patriotic songs.

For a time she managed to keep in touch clandestinely with her son Zbigniew, who was an Auschwitz prisoner (No. 125727), but was first held in Birkenau. They sent secret messages to each other. Later, when Zbigniew was in Auschwitz I working as an orderly in Block 21, it was much harder to stay in touch, but they managed to get news of each another in a roundabout way, via their Warsaw home. But thanks to the fact that both mother and son were working in the prison hospitals, they did manage to meet on two occasions, hug, and have a chat. Dr Kączkowska managed to come over to the X ray unit in Auschwitz I, bringing a group of patients with her, and make use of the opportunity to see her son.

Pencil drawing of Dr Zofia Kączkowska in 1943, made when she was a prisoner in Auschwitz-Birkenau, by an anonymous artist and fellow-prisoner.Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (Medical Review – Auschwitz), 1977.. The original is preserved in the State Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum collection.

The pencil portrait of Dr Kączkowska, drawn by one of the women prisoners, comes from this period. It is a good likeness, showing her with her hair cropped and a somewhat lacklustre look in her eyes.

Just before New Year 1944 Dr Kączkowska started to run a high temperature. Dr Białówna diagnosed her with the typhus fever she had dreaded so much. At first her condition seemed to be taking a mild course. She wanted to see her son. SS Obersturmfürher Dr Hans Wilhelm König, who was a Lagerarzt (SS camp physician) at the time and sympathetic to her, promised he would make her wish come true. Alas, already on 1 January 1944 Dr Kączkowska’s condition deteriorated considerably. She lost consciousness and kept mumbling something the people around her could not understand. The left side of her face was paralysed, and her right arm developed a tremor. Dr König did not keep his promise, and Zbigniew was not brought in to see his dying mother. Her friends, the Polish, Czech, and Jewish women prisoner-doctors cared for her lovingly. They took turns constantly attending by her bedside. They washed her and helped her drink, and “organised” clean bedlinen, nightclothes and underwear brought over from “Canada”10 for her. For much of the time she was unconscious. They prayed for her.

When she died her colleagues, the female physicians, wrapped her body up in a white sheet serving for a shroud, put it on a stretcher with the sprig from a fir tree and a white chrysanthemum for a wreath, carried her out of the hospital block and put her on a car which took her to the crematorium in an unprecedented ceremony for a concentration camp, showing how loved and respected she was. “She went up in smoke through the chimney into the freedom she longed for so much,” they said. It all happened on 13 January 1944. She left a lasting memory with her fellow-prisoners.

***

This biographical note was compiled on the basis of the following source materials:

- Information from Dr Kączkowska’s son, Prof. Zbigniew Kączkowski, survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau (No. 125727), Buchenwald-Dora (No. 79279), and Ravensbrück (No. 14298);

- The account dated 26 March 1975 I received from Dr Irena Białówna, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor (No. 43117);

- Passages from the unpublished memoirs of Janina Komenda, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor (No. 27233);

- An excerpt from a 1945 letter from Jadwiga Leszczyńska, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor (No. 21170) to Izabela Mandukowa;

- Bronisława Petecka’s letter of 22 November 1975 to me;

- Father Józef Szarkowski’s letter of 22 November 1975 to me;

- Information sent on 21 February 1969 by the Red Cross International Tracing Service at Bad Arolsen to Prof. Zbigniew Kączkowski.

***

Translated from original article: Kłodziński, S., “Dr Zofia Kączkowska.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1977.

Notes

- Doctor Medicinae Universae—the degree awarded in Austria to students graduating in Medicine, corresponding to the American MD degree. Until 11 November 1918 Kraków and Prague were in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and their educational systems followed the Austrian scheme.

- In the 1920s the Polish government established a large, modern port at Gdynia, on the Polish stretch of the Baltic coast.

- Michał Siedlecki (1873–1940)—Polish zoologist and expeditionist; died in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

- Jan Raszka (1871–1945)—Polish sculptor, painter, engraver and medal designer; worked in the Modernist, Cracovian Secession, and art deco styles.

- Dr Wanda Bobkowska (1880–1948)—historian of education, biographer, and women’s social activist, one of the first women to hold an academic appointment as a lecturer and tutor at the Jagiellonian University.

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Paul Fuchs (1908–1983)—SS and Gestapo officer. During the invasion of Poland in 1939 served in an Einsatzkommando (German task force for the elimination of Polish citizens on the Herman wanted list). Later head of SS counter-intelligence for Distrikt Radom. Believed to have worked for the West German and American intelligence services after the War.

- AK—Armia Krajowa (the Home Army), the largest underground resistance force operating against the Germans in occupied Europe.

- Danuta Czech’s Auschwitz Chronicle 1939-1945 (1997; original Polish title Kalendarz wydarzeń w KL Auschwitz, first edition 1992) gives a timeline for the history of Auschwitz based on extant records.

- Traditionally in Poland the main Christmas celebrations are held on Christmas Eve, with a special family dinner.

- “Canada” was the prisoners’ name for the warehouse in which the belongings confiscated from new arrivals to Auschwitz were stored.

All notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.