Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English.

Far more seems to have been written so far on the prisoner-doctors of Auschwitz I than on the Polish medical staff incarcerated in Auschwitz II (Birkenau). Hence it would certainly be worthwhile to consider the persons who rendered distinguished service in the prisoners’ hospitals of Birkenau, especially the women doctors. One of them was Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska, who died in Zakopane on 14 July 1976 and was laid to rest two days later in the distinguished persons’ cemetery in that town.1

Dr Łaniewska came from a medical family. She was born on 27 April 1899 at Cezarówka, Podolia, as one of the 13 children of Jarema Wołk-Łaniewski, a physician and social activist, and his wife Eugenia née Żywult. Katarzyna attended Russian schools and passed the Russian school-leaving examination2 in 1918, and when the family moved to Warsaw, she took a Polish matura (school-leaving examination) for external candidates at the mathematics grammar school for boys on plac Lelewela. On 15 May 1920 she married Stanisław Łaniewski, the adopted son of her paternal uncle Mikołaj Wołk-Łaniewski.

On 27 April 1929 she graduated in Medicine, obtaining a Doctor Universae Medicinae3 degree (Certificate No. 2047) from the University of Warsaw. In 1928–1932 she was an intern, working in several Warsaw hospitals, including the First Internal Diseases Clinic of Warsaw University Hospital4 under the supervision of Prof. Witold E. Orłowski,5 and in the Wolski Hospital6 under the guidance of Dr Kazimierz Dąbrowski7 for the practical part of her internship. She also completed Prof. Witold E. Zawadowski’s8 radiological course and a course on tuberculosis and its prevention. When her father died, the family’s financial situation deteriorated and Katarzyna had to help out with the maintenance of her siblings. To make matters worse, she fell seriously ill herself and had to keep to her bed for a year, but she did not give up her studies and even had a daughter.

She worked in several TB advisory centres in Warsaw (from 1932 at the one on ul. Marymoncka, and from 1935 to 7 May 1943 at No. 12, ul. Srebrna), and in Prof. Zdzisław Gorecki’s9 lung disease ward in St. Stanislaus’ Hospital,10 where she was in charge of the X ray station. In 1935 she left her job in this hospital for an appointment in the First Internal Diseases Clinic, when Prof. Gorecki succeeded Prof. Orłowski as its chief physician. She ran the Clinic’s lung diseases ward, providing treatment for suppurative diseases, pneumonia, and tuberculosis, and continued in this job until the day of her arrest.

As I have been informed by Dr Łaniewska’s daughter, in August 1939 she was recalled from her holiday leave to set up an emergency rescue and sanitary centre in the Holy Spirit Hospital,11 at No. 12, ul. Elektoralna, Warsaw, which would be needed in the event of the outbreak of war. And that is indeed where she was working when the War broke out. From then on, Dr Łaniewska spent most of her time there, on continuous, 25-day spells of duty, practically living there but with only short spells of sleep. She was overburdened with a heavy workload, but persisted in dispensing treatment to the sick and wounded, casualties of artillery fire and air raids, trying not to slip on the blood clots that littered the floor. She wore a helmet a soldier had put on her head. At this time she broke a metatarsal bone and her foot swelled up, but remained undaunted, put on an elastic bandage and carried on despite the pain, dressing wounds and working with the surgeon Dr Jokiel and Prof. Kaczyński,12 who continued to operate; or if there were too many casualties to operate, all they could do for them was to administer large doses of morphine.

Already on 4 September, a bomb hit the hospital’s storage facilities, so there were tremendous problems with providing food for the patients, wounded, and hospital staff. Yet despite this setback, they continued to manage for the long spell of Warsaw’s defence ahead of them. On 25 September a heavy air raid left the Holy Spirit Hospital in utter ruins. Many of the wounded and staff were killed. Those of the wounded whom the staff managed to evacuate were moved to Mirów Market.13 Elzbieta Łaniewska-Łukaszczyk recalls:

Mother and I, Dr Halina Monczarska and her daughter, Dr Stein,14 who was later killed in the ghetto, and many other people were partially buried under the debris. When we managed to get out, we had a trek of over half a day through the burning city to plac Teatralny. That’s where we were when Warsaw surrendered.

Under the German occupation of Poland, Dr Łaniewska continued to work with Prof. Gorecki in the nursing college building on ul. Koszykowa, and quite soon joined in the secret operations of BIP,15 whose commanding officer was Col. Jan Rzepecki16 (nom-de-guerre Prezes). On 23 April 1943 Dr Łaniewska’s husband, who was in the underground resistance movement as well and used the nom de guerre Dach (“Roof”), in a unit called Wachlarz (“Fan”), was arrested in Kiev, brought to Lwów,17 and confined in the ul. Łąckiego prison. On 7 May 1943 the Gestapo arrested Dr Łaniewska, taking her from her home in the Żoliborz district of Warsaw.

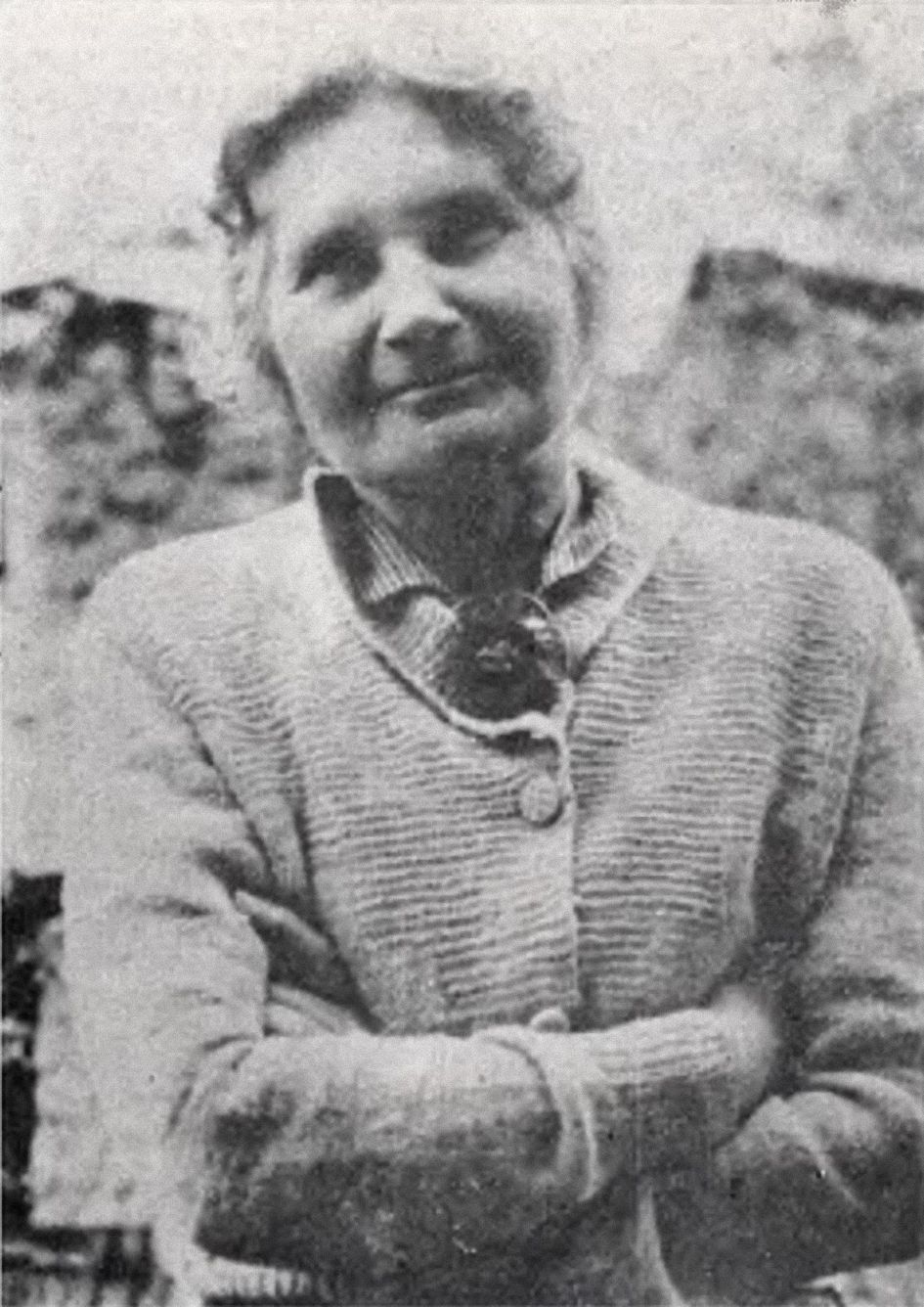

Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska. Source: Ciesielska, M. Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau, Warsaw 2015.

She was held in solitary isolation in the Pawiak jail until 29 May 1943 and an investigation was held with a series of ruthless interrogations in the headquarters of the Gestapo on ul. Szucha. On 29 May, the day of a mass execution in the Pawiak jail, she was taken to Lwów and put in the ul. Łąckiego jail, where again she was tortured during interrogations. She had nearly all her teeth knocked out, and her jawbone was broken, leaving her with a ruptured eardrum. But she did not disclose any names. Then she was put through a confrontation with her own husband, but the Gestapo did not learn they were man and wife and thought she was just Dach’s cousin.

The following passage comes from the manuscript18 of Dr Łaniewska’s recollections of how and why she survived Auschwitz-Birkenau:

[T]he Łąckiego prison in Lwów trained me for the concentration camp. There were no bunks in the cells, you had to sleep on the bare floor, the food was poor and you went hungry; my fellow-inmates were so debilitated that they would faint during roll calls. Exercise occurred at irregular intervals of 10–12 days in a bleak prison yard paved with gravestones from the Jewish cemetery. You could wash at irregular intervals, too, once every 12–14 days. To get to the showers you had to pass through the SS-men’s room naked, and you got a variety of “fine” comments, you were pushed about and called names.

From the Łąckiego jail Dr Łaniewska was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Stanisława Gogołowska, a survivor who was put on the same train for the concentration camp, recalls that there were about 350 women and over a thousand men on it. At first, when a fleet of tarpaulin-covered lorries arrived in the prison yard, it seemed that—as usual— they would take the prisoners to Piaski,19 to be shot. There was turmoil, the SS men were lashing out at the women, who were praying and lamenting, while Dr Łaniewska’s dignified composure encouraged them to calm down to stop the humiliating treatment and the violence against them.

Their journey to Auschwitz took 5 days and 4 nights. As Gogołowska tells me, each of the cattle carriages on the train was jam-packed with 70 to 75 suffocating, hungry and thirsty women. The atmosphere was tense, nervous and full of uncertainty. Some got fits of hysteria, some quarrelled, some fainted. Gogołowska writes that in this situation

Łaniewska didn’t lose her composure, patience, and sympathetic understanding even for a while. She dispensed medical assistance to her fellow-prisoners, consoling and reassuring them. Her remarkable behaviour had a soothing effect, calming them down and offering a bit of optimism.

They arrived in Auschwitz on 3 October 1943. Łaniewska was registered as No. 64200. On finding herself behind the camp’s barbed wire, she went through a short-lived psychological crisis, which was quite understandable once she realised what kind of a situation she was in. In her unpublished account she writes how, on arrival in Birkenau, all the new women prisoners were herded into the sauna and ordered to strip. Their belongings were taken away from them, they were shaved, and rounded up in a large hall. She goes on to confess that

The sight of a crowd of naked women with their heads shaved and their pubic hair removed, was a nightmare . . . there were a lot of old ladies . . . it all had a horrendous effect on me, and this time I couldn’t take it, either, I was in a state of shock combined with hysterical laughter . . . the kapo (luckily, not a Polish woman) ran up to me and started beating me with a stick, and when I fell down she began to kick me. I think the pain must have revived me. Also my companions were quietly advising me to calm down, because they would need me, and that must have helped, too.

This graphic description shows how deeply she must have experienced this harrowing incident. The period of quarantine Dr Łaniewska spent in Block 25, Birkenau’s “Death Block”, was a nightmare, too. She writes about it in her recollections:

The block was built of bricks and its yard was closed off with a high wall. We were locked in and allocated bunks—apparently each bunk was supposed to sleep four, but we were put twelve a bunk, the overcrowding was dreadful! We took turns to sleep, six a time. The block senior was Adolf Taube’s20 lover, the notorious Cylka,21 who abused us with offensive language and physical violence, she used to order us to stand or kneel while she beat us up. We didn’t get any bowls or spoons from her… Apparently she just had 50 sets of them, so you had to eat your food up quickly and hand back the utensils. There were about 700 women prisoners in the block, the political prisoners accounted for just a small percentage. Dantean incidents occurred when the food pots were brought up. . . . After a few days in the block I went down with Durchfall (diarrhoea)—I was in despair… We were taken out to the toilet just a few times a day. And then—I don’t remember how it happened—Dr Janina Węgierska,22 a veteran prisoner, learned of my plight and smuggled some opium in for me.

After the short but distressing spell in “quarantine,” Dr Łaniewska got a job in the Birkenau prisoners’ hospital, first as a cleaner and later as a doctor in Block 24, the Durchfall ward. In the spring of 1944 she was transferred to Block 23, the internal diseases ward. Her unpublished recollections relate the following incidents which occurred before she was given a physician’s post:

I was working as a cleaner. I have to admit that I found carrying the pots very difficult, so I was pushed about, sworn at, and sometimes hit . . . until one day a miracle happened! A buxom, healthy-looking prisoner came up to me and said, “Dr Łaniewska! You’re here, and whatcha doin’? Carryin’ pots, and there’s no doctor on the block, ’cos our doctor’s sick. I can see you haven’t recognised me. I’m Kazia the orderly who was sacked from the clinic for stealing. I couldn’t find a job in Warsaw, so I moved to Płock and worked in the hospital, but it happened again… so I ended up here! Doctor, you should be treating people, and I’ll carry the pots for you, and scrub the floor.” After arranging things with Dr Wanda Starkowska,23 I stayed in the block working as a doctor, but without being officially appointed by the camp’s management. It was my first windfall. . . . Later I was officially appointed by Lagerälteste Orli24 Wald and an SS physician.

Making use of her new opportunities, Dr Łaniewska immediately took steps to find out what had happened to her companions who had arrived with her from the prison in Lwów and visited them. They were in different blocks. Many of them have Dr Łaniewska to thank for giving them vital assistance, or even for saving their life. Survivor Gogołowska relates the following story illustrating Dr Łaniewska’s activities:

One day I told her about the tragic situation of the sick women in Block 26, which had the infamous sadist von Pfaffenhofen25 for its block elder. She did not let them report for admission to the hospital, beat and abused them. That very evening Kasia Łaniewska came to our block on the pretext of visiting me. She discreetly examined the sick women and managed to handle the matter so diplomatically, that von Pfaffenhofen allowed her to get the most seriously sick inmates to the hospital, and permitted her to give outpatient treatment to a large group of others. . . . For a long time Kasia sent medicines, especially anti-scabies medications, to Block 26, where inmates’ state of health was in a dreadful condition. I was Kasia’s go-between for this particular job.

According to Dr Łaniewska’s recollections, she was greatly helped in her work in the hospital by the parcels of medicine, syringes and hypodermic needles, etc. sent by her sister, Maria Łaniewska, who was a nurse. Luckily, the Aufseherin (guard) responsible for checking parcels never happened to spike any of these prohibited goods, Dr Łaniewska recalled. She had a lot of good ideas. For instance, she used glass tubes and flasks to distil water in which she could dissolve the powdered calcium and glucose that arrived in these parcels and were the basic materials for injections. Despite the primitive way these procedures were carried out, none of her patients ever developed septic shock, shivering, or rapid temperature changes following the administration of these injections. She also managed to set up a primitive thoracentesis apparatus.

She took a brave and ingenious approach to the camp authorities, as the following incident shows. One day, during an inspection of Block 24, the Durchfall ward, the inspector, SS Dr Werner Rohde,26 accused Dr Łaniewska of keeping unregistered typhus patients27 hidden in the Durchfall ward. In her mind she quickly ran through the list of about 700–800 patients in the block and told him there were 86 cases of typhus in the ward, which was much lower than the real figure. Rodhe warned her that if it turned out that this figure was wrong, the entire block would be sent to the gas chamber. Łaniewska resorted to a number of tricks28 to make the figures tally, saved the typhus patients and the entire block, and even earned Rohde’s respect.

Alina Szemińska, a Birkenau survivor, has written at length about Dr Łaniewska’s stance. Alina was an interpreter in Block 17, and later became one of the assistants of “our Doctor Kasia,” as the patients referred to Dr Łaniewska, appreciating her good nature, dedication, sympathetic attitude, and medical skills. Alina puts special emphasis on Dr Łaniewska’s ability to get things done on the quiet, “organise”29 medications and medical instruments, and her high success rate in saving prisoners’ lives by prolonging their stay in hospital. Here is a passage from Alina Szemińska’s letter:

Łaniewska kept a double set of medical records, one with a patient’s true diagnosis needed for her treatment but hidden away, and the official record to be shown to the German doctors. . . . Dr Kasia, such an honest and truthful person, was capable of presenting fake information to Dr Mengele when he came to do his round, and she did it with such ease that butter wouldn’t have melted in her mouth, though she was risking her life. Even when she contracted typhus and was confined to her bunk with a fever, she still tried to manage the medical work in the block and issue instructions on what we should do.

Alina Szemińska writes that Dr Łaniewska provided her patients with a wide range of services—she got extra food for the weakest, procuring potatoes, soup, and other foodstuffs from the kitchen block; she dispensed special care for the children and elderly; she hid patients with psychiatric disorders away from the notice of the Germans; she also engaged in psychotherapy by giving pep talks to her patients to bolster their morale, and by passing on illegal political news; and she got her patients to organise special events with singing and poetry recitals to celebrate holidays and national anniversaries.

She looked after the children in the camp, such as those who were deported there in the aftermath of the Warsaw Uprising.30 Survivor Helena Rozmanit31 remembers Dr Łaniewska asking women prisoners in the hospital block to make toys for these children out of things like bits of coloured blankets.

Dr Alina Przerwa-Tetmajer, another Birkenau survivor, says Dr Łaniewska behaved in a truly remarkable way, she was persevering, kind-hearted, calm, and responsive to every sign of suffering. She enjoyed the reputation of a perfect physician with a lot of professional experience, and very many women prisoners owed her their life. She had a sophisticated sense of social service, for instance “she always knew how to organise something well, and how to distribute things fairly,” Dr Przerwa-Tetmajer writes. She was good at handling dangerous situations which threatened the women’s lives, such as Sortierungen (“sorting sessions”, i.e. SS doctors “selecting” sick prisoners and sending them to their deaths in the gas chambers). In such situations she acted bravely, quickly, and efficiently, hiding those who were at risk, changing diagnoses etc.

1944 came. Dr Łaniowska and the entire women prisoners’ hospital were moved to the Zigeunerlager.32 At the time she was a physician in Block 16, an internal diseases ward for Aryan patients. The women patients who were friends of hers, some of whom, known as “Daughters of Auschwitz” were in her special care, were lodged on the “third-floor” bunks. They decided to defy the Germans and the situation in the camp, and celebrate Christmas in the Polish way with a Christmas tree and a traditional Polish Christmas Eve dinner. An unexpected parcel sent to Łaniewska from Germany came in handy. It contained traditional Christmas wafers,33 a yeast-leavened cake, some onions, and two apples. At Łaniewska’s request, all the people in the block were invited to the dinner. They made a Christmas tree out of a green blanket and “organised” potato soup for everyone. They crumbled the Christmas wafers, diced the cake into little cubes, and sprinkled each cube with a pinch of the crumbs. There was carol singing, and Dr Łaniewska made a speech to cheer them all up. The Christmas tree is now in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

Meanwhile, the front was getting closer and closer. Dr Łaniewska only learned of the evacuation on the night of 17-18 January 1945. Having decided to stay in the camp with the seriously ill women prisoners, she provided the stronger ones who were about to leave for the gruesome journey ahead of them with the most rudimentary essentials, such as clothing, blankets, shoes, food, and medications.

After the evacuation transports had left Birkenau, Łaniewska looked after the patients still in the camp, feeding them, providing treatment, obtaining fuel for the heaters, and trying to keep some sort of order in the midst of the chaos of what remained of the prisoners’ hospital. Again she gave a show of courage, hiding the Jewish prisoners the SS men wanted to round up. She and other inmates cut the barbed wire around the camp’s perimeter, letting stronger prisoners escape.

After the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Łaniewska stayed on the site for a few days, whereupon she set off for Kraków, braving the hardships of winter and the shortage of transport. On arrival, she and a few other survivors did all they could to get the Polish Red Cross to arrange an expedition of qualified medical staff equipped with medicines, food, and clothing to the site of the concentration camp to take care of the thousands of sick and exhausted survivors still there. Only once this assistance had materialised did Dr Łaniewska feel discharged of further duties to her fellow-inmates still in Birkenau; only then did she set off to look for her beloved daughter. She did not know at the time that her mother was dying of pneumonia, or that her husband had been transferred from Lwów to Gross-Rosen and eventually to Buchenwald, where he died. But she found her daughter, who was seriously ill.

She started work in a tuberculosis advisory centre in Skarżysko Kamienna.34 To help her daughter recuperate, in 1946 she moved to Zakopane,35 where she was appointed chief physician of the Tytus Chałubiński Polish Red Cross Sanatorium.36 On 1 October 1948 she became the director of a new TB advisory centre in Zakopane.37 She continued working in both posts, which kept her busy practically all day long, right until she retired in 1972, at the age of 73.

Dr Łaniewska had good reasons to devote her post-war professional activities to the treatment of tuberculosis patients. Dr Alina Przerwa-Tetmajer says that one of those reasons was that she was deeply distressed to watch so many Auschwitz-Birkenau inmates die of TB and not be able to help them at all, because of the hopeless situation in the camp. In the Polish Red Cross Sanatorium she took special care of survivors of the Nazi German concentration camps with the disease. Right to the end of her life she never refused to attend patients who needed help.

Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska, a postwar photograph.. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (Medical Review – Auschwitz), 1978.

Dr Łaniewska was resolute and indefatigable in the post-war period as well. Dr Przerwa-Tetmajer says that there were no bounds to her dynamism and organising skills, and that whenever she could, she would expand and enhance her therapeutic methods, improve working conditions, etc. She always “spoke her mind and kept nothing back,” taking no notice of her interlocutor’s status, which sometimes made her resented, or even the butt of prejudiced opinion. She could not stand indifference to suffering, injustice, or wastefulness. She tried to see the good points in the character of every person she met and put these assets to good use for the whole of society. So no wonder that she was popular with, or even loved and respected by numerous survivors and other patients.

Apart from performing her professional duties, Dr Łaniewska was involved in social work. For over a decade she served as the chairperson of the branch of the health workers’ trade union38 in the Polish Red Cross Sanatorium. As of 1945 she was a municipal councillor in Zakopane; she also chaired the local health committee, served as an inspector for the prevention of tuberculosis, and was an active member of ZBoWiD,39 the main Polish war veterans’ association, and of the war invalids’ union;40 as well of professional associations (the Polish Medical Association41 and the Polish Association for Lung Diseases).42 In 1967 the latter association conferred its honorary membership on her.

In 1963 she had a serious operation, and in 1969 she had a heart attack. She lived only for two and a half years in retirement, but kept her old vivacity right to the end of her life.

She was always busy and full of concern for her patients, and fighting against obstacles, yet she also found time for scientific research. In 1936 she published a paper on diaphragmatic relaxation in the medical journal Polska Gazeta Lekarska. She also wrote on multiple myocardial infarction in pulmonary tuberculosis patients; a hyperglycaemic coma case; partial oxygen and carbon dioxide pressure in healthy persons and patients receiving bilateral pneumothorax treatment; and on the maintenance of mobility of the bronchi and bronchioles in healthy persons and patients receiving pneumothorax treatment. Her papers on the last two subjects were destroyed during the War.

Many survivors and other persons who have written to me have commended Dr Łaniewska’s post-war professional and social work. For instance, Sr. Magdalena Kaczmarzyk43 of the Albertine Sisters recalls Dr Łaniewska’s altruism and readiness to see patients without waiting to be asked, which the Albertines of Kalatówki, Zakopane, had plenty of opportunities to observe. You would have had no trouble to call Dr Łaniewska out to see a patient even in the middle of the night. She was not concerned for her own health; she did not insist on taking a rest or a holiday when it was due, or on keeping strictly to her schedule of working hours if patients needed her.

News of Dr Łaniewska’s death saddened her friends, acquaintances, and very many of her patients. Letters of condolence arrived from all over Poland and abroad. Władysław Bartoszewski44 wrote in his telegram: “For me news of her death comes as a personal shock. The fact that there was such a wise and good person was an inspiring certitude for me and probably for many others in Poland, too. One tries to fend off thoughts of the inevitability of someone like her passing away…” Dr Łaniewska’s obituaries were published in numerous Polish papers and magazines, such as Życie Warszawy, Gazeta Południowa, Dziennik Polski, Tygodnik Powszechny, and Przekrój, as well as in the British press.

Numerous medals and distinctions were conferred on dr Łaniewska, including the Medal for the Tenth Anniversary of the Foundation of the Polish People’s Republic45 (1955), the Distinction for Exemplary Work in the Health Service46 (1952), the Gold Cross of Merit47 (1957), the Victory and Freedom Medal48 (1959), the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta49 (1969), the Gold Badge of the Union of Health Workers50 (1969), the Gold Badge for Merit for the Region of Kraków51 (1971), and the Home Army Military Medal52 (awarded to her 4 times, 1971).

But the sincere and heartfelt memories Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska has left with thousands of people are surely the most valuable reward accorded for her merit and dedication.

***

I wrote this article on Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska on the basis of the following sources:

- Written records

- The manuscript of Dr Łaniewska’s curriculum vitae written by her own hand;

- Dr Łaniewska’s curriculum vitae compiled by her daughter Dr Elżbieta Łaniewska-Łukaszczyk on the basis of written records;

- Extensive relations Dr Łaniewska wrote on concentration camps and sent to me (one dated 8 December 1973, and three undated);

- A letter from Państwowe Muzeum w Oświęcimiu (current English name: the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum), No. IV-8521(2883)77, dated 5 July 1977;

- Dr Łaniewska’s obituary notice.

- Letters received from women survivors of Birkenau:

- Letter of 4 July 1977 from the journalist Stanisława Gogołowska;

- Letter of 22 April 1975 from Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska;

- Letter of 10 July 1977 from Dr Alina Przerwa-Tetmajer;

- Letter of 3 July 1977 from Prof. Alina Szemińska;

- A short letter dated 5 July 1977 from Dr Irena Białówna;

- A short letter dated 31 August 1976 from Irena Przybysz;

- A short letter from Helena Rozmanit (undated); and

- A short letter from Sr. Magdalena Kaczmarzyk (undated).

- Mentions of Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska in publications:

- Jadwiga Apostoł, “Wspomnienia z Brzezinki,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1970: 168.

- Anna Czuperska-Śliwicka, Cztery lata ostrego dyżuru: wspomnienia z Pawiaka 1940-1944, Warszawa: Czytelnik, 1965 (First edition), 225.

- Stanisława Gogołowska, W Brzezince nie umierało się samotnie, Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1973, 213 and 221.

- Alfred Fiderkiewicz, Brzezinki: wspomnienia z obozu, Warszawa: Czytelnik (Third edition), 1962,

- Julian Kiwała, “Szpital w obozie żeńskim w Brzezince na przełomie lat 1942-1943,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1965: 114.

- Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, Z otchłani: wspomnienia z lagru, Częstochowa: Wydawnictwo Księgarni Władysława Nagłowskiego; Poznań: nakładem Drukarni św. Wojciecha, 1946, passim.

- Ella Lingens, “Problemy narodowościowe w szpitalu kobiecym w Brzezince,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1966: 111.

- Jan Masłowski, Pielęgniarki w drugiej wojnie światowej, Warszawa: Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich, 1976, 132 and 134.

- Irena Perkowska-Szczypiorska, Pamiętnik Łączniczki, Warszawa: Czytelnik, 1962, 256.

- Seweryna Szmaglewska, Dymy nad Birkenau, Warszawa: Czytelnik (Eleventh edition), passim. English translation: Smoke over Birkenau; transl. from the Polish by Jadwiga Rynas, Oświęcim: The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum; Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 2001.

- Seweryna Szmaglewska, “Sylwetki lekarzy, więźniów Oświęcimia,” Służba Zdrowia: pismo pracowników służby zdrowia (Warszawa: Lekarski Instytut Naukowo-Wydawniczy) 1963: 11, 4 and 12, 3.

- Leon Wanat, Za murami Pawiaka, Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1972, 504.

- Krystyna Wigura, Długa lekcja, Warszawa: Czytelnik, 1970, 225.

- Helena Grunt-Włodarska, “Ze szpitala kobiecego obozu w Brzezince,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1970: 213. English translation: “Recollecting the women’s hospital at Birkenau,” online at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz .

I am indebted and would like to express my heartfelt thanks to Dr Elżbieta Łaniewska-Łukaszczyk, who provided me with the largest amount of information for this article on the late Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska.

***

Translated from original article: S. Kłodziński, “Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1978.

Notes- Cmentarz Zasłużonych na Pęksowym Brzyzku, Zakopane.a

- At the time, Poland was still partitioned between three neighbouring powers, Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary, until 11 November 1918, when the country’s independence was restored.a

- Official name of the first-level medical degree in Poland at the time.a

- I Klinika Chorób Wewnętrznych UW.a

- Witold Eugeniusz Orłowski (1874-1966), Polish university professor of internal medicine. During World War II he served as dean of the Medical Faculty of the secret University of Warsaw, training students after the Germans had closed down all of Poland’s universities, colleges, and secondary schools. Source: https://www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl/a/biografia/witold-eugeniusz-orlowski.a

- Szpital Wolski, a hospital in the Wola district of Warsaw; see Stanisław Bayer, “Episodes from the story of the hospitals of the Warsaw Uprising,” on this website.a

- Dr Kazimierz Dąbrowski, director of Wolski Hospital as of 1927. “Kartki z historii” [History pages], Pneumonol. Alergol. Pol. 2006; 74: 431–4. www.journals.viamedica.pl.a

- Witold Eugeniusz Zawadowski (1888-1980), pioneer of Polish radiology.a

- Prof. Zdzisław Gorecki (1895-1944). See https://www.1944.pl/powstancze-biogramy/zdzislaw-gorecki,14696.html.a

- Szpital św. Stanisława.a

- Szpital św. Ducha.a

- Prof. Jerzy Ryszard Kaczyński (1916-2011). Physician and combatant (in the rank of lieutenant) in the Warsaw Uprising. See https://www.1944.pl/powstancze-biogramy/jerzy-kaczynski,19396.html.a

- Hale Mirowskie, a large street market in the Mirów district of Warsaw.a

- Józef Stein (?-1943), taught anatomy in the secret medical courses organised in the Warsaw Ghetto, directed the Jewish hospital on Umschlagplatz (jointly with Dr Anna Braude-Hellerowa) and died during the Ghetto Uprising. See https://www.umb.edu.pl/medyk/tematy/historia/tajne_nauczanie_medycyny_w_warszawskim_getcie_ and http://www.swieccyzydzi.pl/lekarze-getta-warszawskiego.a

- Biuro Informacji i Propagandy AK, the Information and Propaganda Bureau of the Home Army.a

- Jan Rzepecki (1899-1983) senior officer in the Polish AK underground resistance army during World War II. See https://www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl/a/biografia/jan-rzepecki.a

- In the pre-war period the city of Lwów belonged to Poland. It is now in Ukraine, and known as Lviv.a

- The title of the manuscript is “Jak i dlaczego przeżyłam Oświęcim-Brzezinkę.”a

- Piaski, a sandy area in Lwów’s Jewish cemetery, during the War an execution site where the Germans killed many victims, mostly Jews from the Janowski concentration camp. See https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/miejscowosci/l/703-lwow/116-miejsca-martyrologii/47969-piaski-miejsce-egzekucji.a

- SS-Unterscharführer Adolf Taube (1908-?), Nazi German war criminal, served in the womens’ camp at Birkenau.a

- For more on Cylka (aka Cilka), see the testimony of Auschwitz and Ravensbrück survivor Stanisława Rachwał in Zapisy terroru. Chronicles of Terror, online at https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/publication/3713/edition/3694/.a

- See Maria Ciesielska, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschiwtz-Birkenau (1942-1945), 122-123. Online at www.polska1926.pl.a

- Wanda Starkowska (1897-1944), a doctor from Poznań, arrested and sent to Auschwitz in 1943. Maria Ciesielska, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-1945), 144-146. www.polska1926.pl.a

- Orli Wald (1914-1962), a German Communist and anti-Nazi imprisoned in Auschwitz.a

- Kapo Pfaffenhofen-Chłędowska is mentioned in the testimony of Auschwitz survivor Maria Świderska in Zapisy terroru. (Chronicles of Terror), online at https://zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra.a

- SS-Obersturmführer Dr Werner Rohde (1904-1946)—SS physician and war criminal; served in Birkenau. After the War he was apprehended, tried, and executed.a

- In the German concentration camps the official policy on typhus was to exterminate prisoners suffering from this disease.a

- The original article mentions the use “blood mixtures” (Polish “koktajle z krwi”), as one of the methods of saving prisoners. This unclear expression may refer to the practice of presenting to the SS the results of blood samples of healthy prisoners rather than those infected with typhus, to save the latter.b

- In the prisoners’ jargon, “organising” things meant procuring them by illicit or illegal means.a

- The 1944 Uprising, not to be confused with the Ghetto Uprising of April 1943.a

- Helena Kubica, “Pomoc dzieciom udzielana przez dorosłych więźniów w KL Auschwitz,” Pomoc dzieciom w czasie wojny. Sympozjum. Warszawa: Fundacja Moje dzieciństwo, 2002, p.78. Online http://www.mojewojennedziecinstwo.pl/pdf/sympozjum_2.pdf.a

- The Gypsy family camp, section BIIe, Birkenau, set up by Mengele, who conducted experiments on its Roma and Sinti inhabitants. On Himmler’s orders, on the night of 2-3 August 1944 all of them were sent to the gas chambers, leaving the whole section vacant. See http://auschwitz.org/muzeum/aktualnosci/63-rocznica-wymordowania-romskich-wiezniow-zigeunerlager,550.html.a

- The Christmas Eve dinner starts with a prayer and the exchange of these wafers and Christmas wishes.a

- Poradnia Przeciwgruźlicza w Skarżysku-Kamiennej.a

- Zakopane, in the Tatra Mountains, is a sports and health resort, popular with convalescents recovering from lung diseases.a

- Sanatorium PCK im. Tytusa Chałubińskiego w Zakopanem.

- Poradnia Przeciwgruźlicza Polskiego Instytutu Przeciwgruźliczego.a

- Związek Zawodowy Pracowników Służby Zdrowia.a

- Związek Bojowników o Wolność i Demokrację (the Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy).a

- Związek Inwalidów Wojennych.a

- Polskie Towarzystwo Lekarskie.a

- Polskie Towarzystwo Ftyzjopneumonologiczne; current name (since 2006) Polskie Towarzystwo Chorób Płuc.a

- Sr. Magdalena Kaczmarzyk of the Congregation of Albertine Sisters Serving the Poor (born 1917)—a historian of her religious congregation.a

- Władysław Bartoszewski (1915-2012), Polish historian, journalist, politician and social activist, World War II combatant and Auschwitz survivor.a

- Medal 10-lecia Polski Ludowej.a

- Odznaka Wzorowego Pracownika Służby Zdrowia.a

- Złoty Krzyż Zasługi.a

- Medal Zwycięstwa i Wolności.a

- Krzyż Kawalerski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski.a

- Złota Odznaka Związku Zawodowego Pracowników Służby Zdrowia.a

- Złota Odznaka za Zasługi dla Ziemi Krakowskiej.a

- Medal Wojska Armii Krajowej.a

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator of Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—note by Maria Ciesielska, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.