Author

Wacława Zastocka (1913–2002) served in the rank of captain in the office of the high command of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), the main Polish underground resistance force, during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. Sources: www.1944.pl; krakowianie1939-56.mhk.pl.The work published over the past 33 years1 on the medical profession during the War has given us the biographies of numerous admirable military physicians who kept their faith to the very last to the principles of medical ethics and the soldier’s oath. One of the personalities who certainly merits a place in the pageant of Polish “white coats” who may and ought to be regarded as shining examples of patriotism and the heroic mentality is Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa.

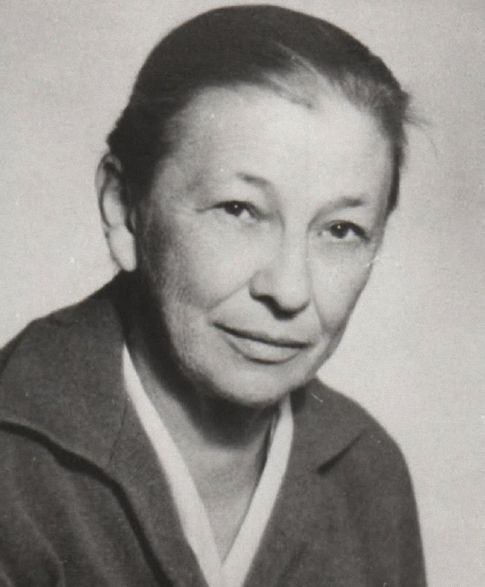

Dr Baraniecka Szaynokowa. Source: Ciesielska, M. Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau, Warsaw 2015.

She was born on 6 December 1898 in the village of Rudenka near Kiev.2 Her father, Ignacy Baraniecki, was a forest ranger and administered the Branicki family estate.3 She attended Peretiatkowiczowa’s4 Polish grammar school for girls, and completed her secondary education in 1915, going up to Kiev University for Medicine. The developments in Ukraine that followed the outbreak of the October Revolution were not conducive to further study. Baraniecka managed to complete two years of Medicine at Kiev. At the age of twenty she witnessed the civil war in Ukraine, the cruelty and reign of terror perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists and the brutality of the German occupying forces. She saw Kiev passing from the troops of one to another of the many belligerents, and the memory of those years would haunt her for the rest of her life.

Wanda Baraniecka had been brought up in the Polish patriotic spirit and commitment to the struggle for Poland’s independence, and was one of the first to join the women’s division of the Kiev branch of POW5 (in 1918) and contribute to its pro-independence work. Having been separated off from her family, she managed to overcome daunting obstacles and leave Kiev. In April 1920 she arrived in Warsaw, where she wanted to continue her interrupted medical studies. She enrolled for the third year of Medicine at the University of Warsaw. At the same time she started work in Piotrków Trybunalski military hospital, and was a resident of that city until 1921.

Wanda continued her activities in the patriotic student milieu, keeping abreast of the rapid military and political developments of those times. On 14 March 1921 she boarded a train for Silesia for persons with the right to vote in the forthcoming Plebiscite6 and left for Zabrze to dispense medical assistance. This is what she wrote in her autobiography about that period in her life:

In Zabrze I was put up in Dr Hager’s7 house, and on the following day I went to Bytom to report at the hotel where the Polish Plebiscite Committee had its headquarters. I naïvely declared out aloud that I had come for the Plebiscite and Uprising, and met with a very severe response. I was so mortified I went out into the corridor and cowered in a corner, not knowing what to do. I was still hoping that someone would turn up and endorse my belief in the need for an uprising. Then a man came up to me (it was Mr Przedpełski,8 as I later learned; I don’t remember his nom-de-guerre). “Were you in POW?” He asked. “POW NK3, Kiev,” I said. He told me to come in the afternoon to Mrs Chmurska’s9 in Zabrze. Halina Wojciechowska10 and her future husband Władysław Sołowij (nom-de-guerre Jan Falk) had lodgings there. Przedpełski and Grażyński (Borelowski)11 arrived for a briefing and took the oath from me. My task was to supply the 2nd Kościuszko Infantry Regiment (stationed in Zabrze) with medical dressings, kits, and instruments. There was no problem with recruiting qualified paramedics and nurses; there were plenty of them, trained by the Germans in the army, coal mines and steelworks. Antonina Rokicka-Niedbalska12 and Bożena Sołtys-Schayer13 had been training nurses for some time already. I did a bit of travelling over the area, getting to know the commanders of the battalions and companies and their deployment. I got to know the network of courier and liaison girls, who were managed by Halina Wojciechowska-Sołowijowa. Finally, in the second half of April I was ordered to report to Szopienice to collect medical and sanitary supplies. . . . Finally, at 2 a.m. on 3 May [1921] I set off with the Zabrze company for the Sicherka.14

Wanda Baraniecka’s dedicated service and contribution to the Third Silesian Uprising did not go unnoticed. Dr Alfred Kolszewski,

A decade later, Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa published an article in Dla Przyszłości, the monthly magazine of the Women’s National Defence Training Organisation16 to mark the tenth anniversary of the Third Silesian Uprising. She concluded her recollections with the following remark:

It was not the fault of those anonymous, rank-and-file heroes that they were ordered to retreat. They had done their duty—they had yet again soaked the soil of Silesia with their blood, which neither enthralment nor Prussian boots had managed to deprive of its Polish character. Today, on the tenth anniversary of the Uprising, I pay tribute to you, People of Silesia, because I know you and love you, because I went through that blood-soaked chapter of our history together with you.

Baraniecka’s patriotic stand in defiance of German aggression had matured already by 1921 and the Third Silesian Uprising.

On leaving Silesia, Wanda Baraniecka married Władysław Szaynok, a student of Lwów Technical University and a veteran of the Silesian Uprising. They settled in the city of Lwów,17 where she completed her medical studies, graduating from Lwów University in 1925. At this time she continued her social work as a member of a women’s civil organisation.18 After three years of work in a hospital, she was appointed a school physician and also ran a school advisory service for problem children.

At an information meeting held in 1928 for the women’s military training movement, she met its activists, women veterans of the First World War, the Polish War, POW members, representatives of the Women’s Voluntary League19 and other organisations, and learned of the achievements of the Social Committee of the Women’s National Defence Training Organisation. That was when she became fully committed to the service of this organisation, both as a doctor and as a social activist. Her first duty was to serve as the doctor attending its summer camp at Garczyn near Kościerzyna; subsequently she completed an instructor’s course, which qualified her to become the leader of the Organisation’s Lwów branch.

In 1929 she completed a sports medicine course and became a pioneer in the field, running an advisory service for a physical and military training centre in Lwów. She observed an urgent need to improve the physical fitness of young working women, and set up a summer training camp for factory girls at Skole near Lwów. To keep them fit on a continuous basis, she trained a group of leaders to conduct 15-minute gym sessions for girls in their workplaces.

The specific features of Wanda’s character, her honesty, profound sense of responsibility, modesty, sincerity, openness, vivacious temperament, and her straightforward, sympathetic attitude to people earned her respect and made her popular with her colleagues at work and her “dependants.” The way she spoke, with the lilt characteristic of the speech of the inhabitants of Poland’s Eastern Borderlands, her great sense of humour, and forthright manner in relations with colleagues and patients made her an outstanding and well-liked persona. After giving a talk on chemical warfare during the summer camp, she earned a nickname, Iperyt (Mustard Gas), that stuck to her for many years. During the summer months she was always available for duty as a Women’s National Defence trainer. In 1930 she served as leader of Garczyn camp; in 1931, 1932, 1933, 1935, and 1936 she performed the same duty at the Skole camp, and in 1934 at a camp in Rozewie on the Baltic coast. Her experience and continuing education for the theory (an advanced instructor’s course) qualified her for the leader’s appointment in the Przemyśl branch of the Women’s National Defence Training Organisation (1933).

In 1934 her husband Władysław died, leaving her with their daughter Halina, who was still a small child. Wanda was extremely busy professionally and dedicated to her social work, but she did not look after her own health properly, which put her at risk of contracting tuberculosis. Out of concern for her daughter’s welfare, she decided to send Halina to stay with her grandparents in the Lublin region of Poland, but she did nothing to modify or reduce her work schedule or her social commitments.

Important new developments in Wanda’s life came in 1936. The Women’s National Defence Training Organisation sent her to Berlin as an observer for the 1936 Olympics, from which she brought back a host of apt remarks and profound reflections on the way the Nazi Germans were educating young people. On her return from Berlin she was transferred to Warsaw and appointed officer for Dr Jordan’s Parks20 in the Department for Women’s Physical Education and Military Training at the National Office for Physical Education and Military Training in the Ministry for Military Affairs.

In the 1937-1938 school year a new subject was put on the curriculum of all the secondary schools in Poland—civil defence. The Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment21 needed someone who was fully professional to supervise the women’s auxiliary service course now compulsory for vast numbers of girls in Poland’s secondary schools. The Headquarters of the Women’s National Defence Training Organisation recommended Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa for the appointment of school inspector, and this is the post she was in when the War broke out in September 1939.

She was called up on 1 September and sent to the women’s battalion of the Auxiliary Military Forces22 in Lwów to serve as the battalion’s physician. On her way from Warsaw to Lwów she stopped in Lublin, where the head of the local garrison’s medical service appointed her physician of the casualty dressing station. After the evacuation of the commanding officer of the garrison’s medical staff, Dr Szaynokowa stayed in Lublin and took part in the voluntary operations carried out by the Lublin Defence Company23 in the section near the cemetery and later in Hrubieszów, where the Company joined in the defence of a local bridge. The developments that followed forced the Company to disband.

In late October 1939 Dr Szaynokowa returned to Warsaw and immediately reported to Maria Wittek, who was the commanding officer of the Women’s Military Forces24 in the underground SZP–ZWZ–AK25 Headquarters and former commanding officer of the Women’s National Defence Training Organisation, declaring readiness for service in the Polish underground resistance forces. At the same time she dispensed medical services free of charge for the inhabitants of the Czerniakowska and Zagórna area of Warsaw, where she lived, for her colleagues from the Women’s National Defence Training Organisation, for people she knew and their friends—in short, for all who needed such assistance. I am personally indebted to her. In 1942, when I was absolutely exhausted and suffering from anaemia, she provided me with the right medical treatment without being asked. A couple of Campolon26 injections which she procured for me and administered, as well as her sympathetic and friendly attitude put me back on my feet.

In 1940–1941 she worked first in the distribution department, and subsequently in the medical sector of the Women’s Military Forces in ZWZ–AK headquarters, training medical teams for the underground resistance army. In 1942, on completing a special training course, she started work as a Department 227 courier and emissary of the AK headquarters for the eastern territories (Belarus and Ukraine) under German occupation. On two occasions she and I made a courier expedition together to Kiev. She used ID documents made out to a Halina Sobolewska, and her nom-de-guerre was “Dunia.”

On 13 January she was arrested in Kiev, in the residence of “Tomasz,” head of Polish intelligence for Ukraine. His apartment had been set up as a trap (everyone who came to it was arrested). That was when I lost touch with her: I last saw her at 8.30 a.m. on 13 January 1943, as she was leaving my lodgings in Kiev, to deliver some documents for me to Tomasz. I didn’t see her for the next two decades, as it later turned out. Once she entered his apartment, she was caught in the trap, but managed to keep her cool, stick it out, and handle the first interrogations well enough to avoid the disclosure of her true identity and mission. The Kiev branch of the Gestapo removed her from the large group of Polish intelligence agents apprehended at the time in that city and other places in Ukraine, and kept her for two months in prison in Kiev. During the rest of the investigation she kept steadfastly to what she had said in the first interrogation and put up with torture, confinement in a dungeon, and hunger. Her mind was concentrated and watchful. She observed her fellow-prisoners carefully. In her recollections written in 1948, five years after her arrest, she gave an account of the period, leaving an invaluable record of the events, because she was the only one of the Polish intelligence agents arrested in Kiev in 1942 and 1943 to survive. All the rest were executed. This is what she wrote:

“Take her away to the prison!” Hauptmann Fischer ordered. I was led down. In my imagination I saw images of dark, damp dungeons. We came up to a door with iron bars over it. A key clinked, the door opened, and I was astonished to see a corridor brightly lit up by electric lights. On one side there was a line of windows with curtains drawn up over them, and on the other side a row of doors with peep holes covered up with little metal guards. Rather like hospital doors, except for the peep holes. Suddenly the figure of a stocky woman in a white hospital coat rose up in front of us. She exchanged a few words with the guard. “Any lice?” she asked quite sensibly in Russian. “None!” “Then there will be,” was the authoritative remark I got. The last in a long line of doors opened. I entered the cell and slumped down on a bed. Suddenly I was surrounded by a group of women, most of them in shoddy clothes. “What’ve they arrested your for?” “What’s the weather like?” “Is it very cold?” “What do the papers say?” they asked in a torrent of clamorous questions. I replied in monosyllables. I hadn’t yet got over the shock caused by the interrogations, which had gone on all day and night, and another day almost without a break, or my attempt to get run over by a passing vehicle, and I was thinking that this was the end, of my mission and my life.

I was sitting on a narrow iron bed, looking around half-consciously, taking in the situation and scanning the people around me. There were fifteen women of different ages, shapes and sizes, all milling around the long, narrow cell with four beds in it. A Gypsy woman’s raucous song was coming from the neighbouring cell. In “our” cell there were people shouting, singing several songs all at the same time, and even dancing. As I later learned on comparing conditions in other prisons from personal experience or from what fellow-prisoners told me, there was a fair degree of freedom in the Kiev jail. Its prisoners were completely isolated off from the outside world. No news and no parcels. You were as good as dead. But you were allowed to indulge in loud conversations, singing, or even dancing in your cell.

Finally, when the noise got unbearable, Tamara, a tall woman with a haggard face and wearing a grey gown that was too long, quietened down her companions. She must have enjoyed some kind of authority, because the noise subsided, and after a while one of the young girls started to sing Ukrainian songs. She had a pleasant, melodious though untrained voice, and after a while I was under the spell of her songs. Slowly my apprehensiveness started to fade, and my mind was lulled by the song, which carried me far back to the irretrievable past of childhood and early adolescence. I was lulled by that song, which glided over the immeasurable expanses of Ukraine and had been the companion of my childhood and young years. And now, in that Kiev jail, it was soothing and comforting me, like the dear hand of someone who had long since passed away… The song finished, and gone was the enchantment. The cell’s inmates started to retire for the night.

That was a very complicated task: you had to put sixteen people to bed on four narrow, metal bedsteads. This is how the problem was resolved: six people slept two a bed on three of the beds. The thin mattress was removed from the fourth bed and used as a head rest for all the other inmates. It was put on the floor by the radiator, with two blankets spread out next to it, and the rest of the inmates dossed on it in order of “seniority,” that is the length of time they had spent in prison. I was on the end, with no mattress and no blanket under me. So I just lay down on my coat and somehow managed to make it through that desperately long night. A grey, winter break of day came, lazily seeping in through the gaps in the wooden boards covering up the window. The cell started to liven up, with people getting up, dressing, tidying the mattresses and blankets and making the beds. We got a hot beverage supposed to be coffee and a slice of bread made of millet, not more than 150 g each. Then we waited to be taken out to the washroom and toilet, and eventually for lunch. Lunch! Half a litre each of millet groats, watery and overcooked—you were lucky if you found half a potato in your portion. There was no supper, or more precisely, another helping of millet groats was what was served for supper to Volksdeutsche,28 children, and inmates who had been inside the longest and were beginning to swell up due to starvation. The rest had to look on…

One day the door opened and there stood dear old Mucha S. Frau Bigosch, the hygienist prison warden, asked her usual question, “Know her?” We gave each other the eye, and the two of us said, “No!” Mucha was animated. She told the nosey parkers that she had been arrested for bootlegging and gleefully explained what her purported still looked like. She plotted a course to reach me and uttered just a single word, “When?” “13 January, from Tomasz’s,” I replied. That was all we could say. We had to be careful. A couple of days passed. Now and again we could exchange a word or two, but it wasn’t exactly a good way to communicate. We were helped out by Hela. She was sitting on a bed, talking to Mucha. Suddenly she said to me, “Halina, why are you sitting there on your own? Come up to us and let’s talk.” I came up and sat down next to her. Hela embraced us and whispered, “Now you can talk to each other. I’ll keep watch.” Then she started to chatter. Mucha and I had a quick, nervous conversation. After a while I knew everything. We made an arrangement that we did not know each other, and had never met before. Done! Poor Mucha. She couldn’t even deny the facts. That traitor Jorgis knew all about her. But he didn’t know about me. He’d never seen me. My instinct was right to warn me of him. If the courier didn’t bring those photos of me which I had left with Piotr for a new ID card, perhaps they’ll not manage to prove I was involved in this job...

A fortnight after my arrest I was called up for questioning. The interrogator was Fischer, who did it elegantly, sitting in a chair with a cigarette. He asked a series of tricky, intelligent questions. I stuck to what I had said before. Finally he gave up and said, “You don’t want to come out with the truth,” and then his voice turned hard and he hissed, “but please remember that the Gestapo has methods that make the Inquisition look like child’s play.” And with that nice little promise I was escorted back to our cell. Then it was Mucha’s turn. She was back after about half an hour and packed her things in silence. They moved her to another cell. We exchanged glances to say farewell—forever...

Two months later, Dr Baraniecka-Szaynokowa and several others were sent to the Łąckiego jail in Lwów, under an escort of five German guards. The other arrestees were Ada Zielińska, a Polish intelligence agent arrested in Homel;29 and three other prisoners rounded up in Kiev in April 1942 (one of them was Capt. Stanisław “Dach” Łaniewski, head of the Polish intelligence cell in Kiev and husband of her friend Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska,30 Auschwitz prisoner No. 64200). Their train journey took 40 hours. She was deeply moved to recognise one of the scrawny prisoners, a man with blazing eyes, who was in the same group of prisoners escorted to the prison in Lwów. It was “Łaguna,” a comrade-in-arms from the Kiev branch of the POW, aka “Dach,” who people in Warsaw said had been executed in Kiev in 1942.

She spent 7 months in the Łąckiego jail. On 3 October 1943 she was sent to Auschwitz. She did not break down during the rest of the investigation. No evidence was found to prove that she was in the Kiev spy ring. In Auschwitz-Birkenau she was registered as Halina Sobolewska, prisoner No. 64267. After quarantine in Block 25 she was put in Block 24, the Durchfall31 ward, and in November was sent to work as a nurse in the Revier32 (Block 22), looking after sick Russian children. The scenes from this period that sank deep in her memory are shocking. The headings of the chapters in her memoirs for this time—“Lepers,” “Auschwitz smells of cadavers,” “The Durchfall block”—recall the horror of the way this Nazi German death factory operated. There have been many memoirs and recollections with survivors’ records of their first impressions and experiences of the Auschwitz reality. It would surely be risky, I think, to try to generalise on the matter, and a truism to say that every inmate, whether a man or a woman, went through the first few hours and days in the camp differently, in his or her own, unique way. This is how Dr Szaynokowa described her first experiences and impressions of Auschwitz, in a passage of her memoirs entitled “Lepers”:

After completing all the traditional Auschwitz formalities, such as having my prison number tattooed on my arm, having all my belongings taken away, stripping and having the hair on my head and other parts of my body shaved off, I found myself in a large hall with benches arranged the way they are in an amphitheatre or lecture hall. This was the antechamber to the washroom. I was sure that I would have to go through all of these rituals in any case, so I was in no hurry and let women who were jostling and pushing their way up to the front in a kind of pathological hurry pass me by. I was one of the last to enter the washroom. The sight was so weird that I burst out laughing, to the disgust and annoyance of my companions. It took me a long time to calm down. I guffawed every time I looked at the assembled community. Dear old Mutti,33 Cecylia S., a veteran from the Legions34 with a keen sense of humour, laughed with me. Just imagine about 400 naked women, all of different ages and with clean shaven polls. I must have been just as pretty. But that’s not what I was thinking about at the time, I was just amused by the sight of that bizarre menagerie.

Finally our turn came. It was delightful to take a warm shower and wash off the nasty resinous substance we had had our heads smeared with for reasons of hygiene. We were issued with clothes and undergarments—a short vest, a skirt and a blouse that was so short that every time you moved it came out of your skirt. No stockings or scarves for our bare heads. Two men’s shoes, both for the same foot and at least three sizes too big. A typical outfit for a Zugang or Muselmann.35 After what seemed like an endless wait to get our numbers and triangular badges and letters,36 which stood for the inmate’s nationality and offence, we were marched off to our block. Block 25, where we had been quarantined, was the notorious Death Block; its inmates were women who had been selected in the camp or the prisoners’ hospital and were waiting to be taken to the gas chamber. Unlike other blocks, it was surrounded by a brick wall with barbed wire on top.

We were kept out in the yard until late. Supper was delivered—“herb tea,” a piece of bread (the full daily ration), and a sliver of margarine. At last we were ordered to go into the block. Inside there was a row of bunk beds, all built of bricks. Theoretically, each bunk was for two occupants, but in practice slept 10 to 12 women, due to the overcrowding. The worst bunks were those on the “bottom deck”—they were low, dingy, and full of mud, because at the time the flooring was just hardened earth, not brickwork or cement. We went to bed and made an arrangement that we would sleep on our sides and all turn at the same time “on command.”

After the morning roll call and another dose of “herb tea” with no bread, we were not allowed back into our block. The block senior, a petite, vivacious, pretty and raucous Jewish girl from Slovakia, said we were to go to the Wiese, the meadow, which made us think of a stretch of land still green, though perhaps slightly withering at this time of the year (early October). But there was nothing meadowy about the Wiese in Auschwitz, except the name. It was quite a small area, bordered on one side by barbed wire, and on the other sides by the kitchen, toilets and washrooms, and Block 25. In the middle there was a small building, the mortuary. The ground was clayey and well-trodden by thousands of feet, giving rise to a stretch of slippery, gooey grunge in which you got stuck. The mud in the Wiese was exceptionally foul and stinking for a very simple reason. You could go to the toilet only twice a day, in the morning and in the evening, with a group. If you tried to use the toilet at any other time, you were in for trouble. A couple of old hags sat in the building, and if they spotted a dupe heading for the toilet, one, two or three of them would jump out with sticks and shoo her away, noisily rattling off a string of abuse at her at the top of their croaky voices in the finest Auschwitz dialect. You could come off unscathed only if your legs were still strong enough to dodge the blows. Those old hags were functionary prisoners, usually Jewish women from Slovakia.

In these circumstances, there was no option but to use the more secluded spots on the Wiese. It always entailed a risk of meeting with the boot or stick of a passing functionary for “unhygienic and inappropriate behaviour.” As a large part of the inmates had diarrhoea, the notorious Auschwitz Durchfall, you can imagine what the Wiese was like. In any case, there were crowds on it. Skinny, dirty, ragged creatures strolled along it, on their own, in pairs or threes, holding a variety of items: a sweater, a blouse, underwear, ski trousers etc., or a piece of margarine, sausage, or liver sausage wrapped in a piece of dirty, greasy paper. Next to them sat others who were just as gaunt, holding one of those renowned Auschwitz red bowls containing slices of half-mouldy, soaking wet cabbage leaves. Still others put on display a couple of boiled bones, meatless and slimy. That was the Auschwitz street market. The currency at this time was a ration of bread.

This was the time when big trainloads of Russians were arriving from the territories under German occupation, and before the mass transportation of Jews from Western Europe and Hungary. There was widespread hunger in the camp, and bread was expensive. For a chunk or two of bread in the rationed amount37 you could get a thick ski sweater or ski trousers. People went hungry to protect themselves against the cold. Usually their enjoyment of warm clothes or underwear was short-lived, lasting only to the next inspection or delousing spree, when they would lose it all and revert to the official ragged prison gear. So they had to start all over again, “organising”38 things, or if they couldn’t “organise” them, they had to buy new things in exchange for the all-powerful bread ration. Actually, the heyday of the “bread ration” period was drawing to a close. The typhus epidemic which broke out in November 1943 spread so vehemently that by December there was a surplus of bread in Birkenau. For a short spell in the spring of 1944 the bread ration recovered its former economic leverage. But it was wiped out by the arrival of huge, well-stocked transports of Jews from Western Europe and Hungary which started in May 1944. But that’s another story...

Szaynokowa continues her story with a description of the other people out on the Wiese:

Next to the traders there were groups of particularly emaciated individuals. Clad in dirty, grey robes that hung down loosely on them, they looked like skeletons. The colour of their hair, which had grown since their heads had been shaved clean, was dark or a golden russet, as if tinted by the sun somewhere else in the world. Most of the faces were young, livid-grey, some still with traces of an earlier, striking beauty. The majority had dark, cavernously deep-set eyes. They stood together in groups of thirty or more, clinging to one another or in fact leaning on each other’s backs, warming themselves. The bare legs sticking out from under their frocks were covered with bloated scabs with pus oozing out of them. The same with their arms, which were bare up to the elbows. From time to time they would scratch their arms, legs, all over their body, not caring at all that they were tearing off the scabs with their dirty fingernails, and there’d be little rivulets of blood trickling out from under the damaged skin. They just stood there, swaying monotonously to and fro and uttering something that sounded like a song mixed with a moan. They were girls from Greece, most of them Jewish, the last 200 out of a big transport that had arrived in Auschwitz in the spring of 1944. Not a single one of them survived. All that remained of them was the touching tune of a song about their mother, as well as a few expressions, such as klepsy, klepsy (meaning theft), and Saloniki extra prima, a jocular phrase for something that was especially good and fine. They were devoured up by the climate, hunger, and scabies.

Could anyone have imagined before Auschwitz that you could die of scabies? It turned out you could. Women with untreated scabies, with no chance to change their clothes or underwear, take a bath, or even have a wash, died after a few months of emaciation and additional purulent infections. The whole of their bodies, except for their faces and necks, were covered with oozing scabs. These little clusters of scabbed, miserable creatures were like some sort of nightmarish phantasm depicting a leper colony in the remote Middle Ages. These children of the southern sun were just standing there, warming themselves on each other’s scrawny bodies, casting their woeful song into the cold, grey sky of autumn. The crematorium chimneys were belching up their smoke. Perhaps tomorrow, perhaps next week, or next month at the latest, you, O child of sunny Hellas, inhabitant of the leper colony, will be part of that greasy column of smoke.

The writings and recollections Dr Wanda Szaynokowa alias Halina Sobolewska has left us present a description of her conduct, which was remarkable in the conditions prevalent in Auschwitz. She was preoccupied with thinking how to help helpless child inmates, fellow-prisoners who were weaker and not so resilient to the inhuman conditions; and with putting her ideas into action. She did not write about herself, her tribulations, worries, or her anxiety. In her work in the hospital block for Russian children she focused all her attention on carrying out her duty as a nurse. She was a fully dedicated caregiver, probably doing much more than her superiors in the camp expected, but in accordance with her conscience as a Polish doctor. In her memoirs when she mentions her work, she treats it as something ordinary, steering clear of lofty language and distancing herself off from it, often resorting to irony and humour to highlight dramatic situations. Her keen sense of observation and tendency to ponder on the humanitarian aspect let her describe incidents, situations, and phenomena that others failed to notice. Her own spiritual condition is best shown in what she wrote a few years after her return to normal life:

It was one of those glistening, frosty November mornings just before the crack of dawn. Even Auschwitz was still fast asleep in a heavy, breathless slumber. I was working at the time as a nurse looking after sick Russian children, and I slept in Block 24, the Durchfall block. I tried to rise as early as possible to be first in for work on the day shift. The reasons for this were simple in the Auschwitz way. The children had to be washed, and there were only three basins to cater for the little ones, about three score of them. The one who was first in could take even two of the basins. Those who were late had to wait and could not tidy up their part of the block before breakfast and the doctor’s round. Secondly, there was no running water in the blocks, or in fact at this time it was available in only two of the hospital blocks, Durchfall and the “German” block. So you had to hurry and come in before the others arrived, because as a result of the endless rain and the perpetually potholed passageways being full of wet clay, staff coming into the blocks privileged enough to have running water brought huge quantities of clay into their vestibules. This eventually made the all-powerful block seniors, who were extremely punctilious about cleanliness, fly into a rage. They would rush out, shouting at the top of their voices, which did not make much of an impression on prisoners, who were used to the block functionaries’ continual yelling. However, to back up their verbal arguments, they wielded a big stick, and were deft hands at applying it whenever the need arose. And that was persuasive enough. So folks just scrammed with empty buckets, and the kids were not washed. Having left my dirty and smelly block, in a while I would be dropping into the noise and smell of another block.

All was bleak and quiet. In the east the sky was just beginning to turn grey. I stopped to draw a whiff of the crisp, frosty air into my lungs. There was just one thing on my mind: it was cold, quiet, white and delightful; I wanted to be alone for a moment and take in an extra portion of fresh air. I stopped and gazed at the sky beginning to light up. I took a deep breath and suddenly froze in the middle of inhaling. Through the crisp smell of the cold I sensed another—the smell of corpses. Auschwitz smells of cadavers. Never again did I seek a fresh breeze in Auschwitz. There were none even in the spring, just as there were no birds, which flew well clear of the death camp...

The worst situation was with the bed linen and underwear. We did have sheets, nappies, baby vests and smocks, but far from enough. The ward nurse had from 12 to 20 children of various ages under her care. She had to keep the ward tidy, feed the babies and change their nappies, keep them clean, take their temperatures, carry out the treatments that the doctors ordered, bring in water, dispose of waste in a cesspool that was quite a long way off, and wash the nappies and baby clothes. All this work would have been far too much for one person in normal conditions, never mind the conditions in Auschwitz. The worst was the laundry. She could only do it in a small basin and with hardly any soap, because if she used the soap ration up on the laundry, she wouldn’t have had enough to wash the children. Getting cold water was difficult enough—hot water was absolutely out of the question—and if you went to fetch water, you risked at least a scolding from the block senior. Once you had done the washing, after all that fuss, there was nowhere to dry it. It was November and raining all the time, day and night. And in any case, if you left it out to dry unattended, it was sure to vanish, “organised” in the twinkling of an eye. So you had to hang the washing out to dry on the edges of the beds closest to the hot iron stoves. This was strictly prohibited, so when word went round the blocks that the SS doctor was coming,39 the laundry was promptly stashed away under the mattresses.

The mattresses—that was yet another chapter in the story of this hellhole! There was a lot of bedwetting, even the older and relatively healthy children who had not been properly trained to keep themselves clean wetted their beds. Wet mattresses would simply be turned “dry” side up, and were in a sorry state. It was impossible to get them completely dry. If you put them outside, they would only be soaked in the rain, and you could not change the straw (or more precisely, crumbled particles of straw) filling them. When I took over all these duties, whenever the weather was fine, I would take the mattresses out one after another, try to shake the filling a bit and remove the most putrid straw. Sometimes while doing this, my fingers would come across something soft, alive and moving about in the mattress—a ball of white, lazily wriggling worms. I would throw them out with the rotten straw, but I could never get the mattresses dry...

On 30 April 1944 Dr Szaynokowa was transferred to Ravensbrück, where she was registered as No. 73189. She already knew that Warsaw lay in ruins and the Uprising40 was drawing to an end. She informed the camp’s authorities that she was a physician, and with her usual dedication to saving lives set about keeping Jewish prisoners from selection and death.

Dr Irena Białówna41 is one of the survivors who remembers Dr Szaynokowa from Ravensbrück. They were reunited in that camp in early February 1945, following their evacuation from Auschwitz-Birkenau. Białówna relates that in Ravensbrück Szaynokowa got into serious trouble with the block senior and matron when she protested against the pilfering of patients’ Zulage.42 She wrote the following in a letter to me:

I think that the two of them [i.e. the block senior and the matron] were acting in collusion. Szaynokowa’s complaint to the Oberpflegerin43 against the block senior brought no effect, indeed, it only made matters worse, bringing more reprisals from the block senior.

She was “punished” by being put on a transport of 300 Jewish women condemned to death who were sent out from Ravensbrück on 7 April 1945 for Mehltheuer near Plauen,44 On the night of 15/16 April 1945 the group was liberated by American troops.

After a couple of weeks of being moved from place to place with other liberated prisoners, Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa eventually landed up in Wetzlar, where there was a camp with a group of Polish people whom the Germans had deported to Germany for slave labour. She stayed in this camp until 8 September 1945, working as a doctor. From there she travelled to Meppen, where General Maczek’s Armoured Division45 was stationed. Without taking a rest and disregarding her exhaustion due to confinement in German prisons and concentration camps, she immediately reported for duty in Meppen hospital. Now she could use her real name and when her status as a Home Army officer in the rank of captain was verified, she was granted combatant rights.

In May 1947 she left for England with the women’s battalion, serving as its physician. In late May 1947 she was demobilised and took a job in the internal ward of Chester Hospital.46 She wanted to work instead of drawing an ex-servicewoman’s pension. In 1950 she asked to be transferred to work in the hospital’s psychiatric ward. At this time she took an intensive course of English and passed the final test with flying colours. In 1954 she moved to Bridgend in South Wales and took up an appointment in a local mental hospital.47 She decided not to nostrificate her Polish medical degree, so she accepted the tough conditions imposed by the British National Health Service (much to the disapproval of the Polish ex-servicemen living in Britain after the War) and started work from the bottom rung of the career ladder as a pre-registration house officer,48 gradually rising to specialist registrar and consultant. During an epidemic of smallpox in 1960 she was the only doctor to stay on duty in her psychiatric ward, looking after six patients who had contracted to disease. She had not been vaccinated herself. The staff of the hospital and the people Bridgend were impressed and admired her for this.

At this stage of her life, Dr Szaynokowa visited Poland several times to see her daughter Halina, who had married by that time. After retiring in 1966 she repatriated and settled in Konstancin near Warsaw, committing her boundless energy and enthusiasm for social work to the service of a local welfare organisation.49

Dr Szaynokowa did not enjoy a long retirement. The life of this extraordinary woman was arduous and eventful. She had been a participant in the Silesian Uprisings, a physician and instructor working for the Polish Women’s National Defence Training Organisation, a pioneer of the sports and physical education movement for young working people, a Home Army combatant, a prisoner of the Nazi German prisons and concentration camps, and a doctor looking after British psychiatric patients. It would be hard to give an account in a few sentences of her remarkable, busy life, full of service for her country and humanity at large. Perhaps the best way to sum up her character is the following sentence from one of the testimonials written on the occasion of one of her decorations: “This distinction is conferred on Captain Wanda Szaynokowa, alias ‘Dunia,’ for outstanding valour in her service as a courier and emissary, constantly at risk of hostile enemy action ...” Indeed, “outstanding valour while constantly at risk of hostile enemy action…” But that was not all. There was something profoundly humanitarian about her attitude to people and life—simply the love of humankind and will to serve.

The Cross of Independence50 and the Silesian Ribbon of Valour and Merit (First Class)51 were conferred on her in 1921 for her part in the Third Silesian Uprising. In 1934 she was decorated with the Silver Cross of Merit52 for her achievements in her professional and social work. And finally the Military Order of Virtuti Militari (Fifth Class)53 was conferred on her for her contribution to the Polish war effort during the Second World War, along with the Army Medal,54 which she received four times.

General Jerzy Ziętek’s55 invitation for the unveiling ceremony of the Silesian Insurgents’ Monument and the conferral of a medal to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Third Uprising arrived four days after Dr Szaynokowa’s death. A minute’s silence was observed in tribute to her at the celebrations for St. Barbara’s Day56 on 4 December 1972. She was an honorary member of the Zabrze Association of Veterans of the Silesian Uprisings.57

Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa died suddenly on 6 June 1971 in Praga Hospital,58 Warsaw, after three months of treatment following a heart attack, on the day she was due to leave the hospital.

***

Translated from original article: Zastocka, W., “Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1979.

Notes

- The article was originally published in 1979.

- Under the Partitions (1795–1918), when Poland lost its independence and was partitioned between three neighbouring states (Russia, Prussia, and Austria), a large Polish community lived in Kiev.

- The Branicki, a Polish aristocratic family, had several large properties in the vicinity of Kiev.

- Wacława Peretiatkowiczowa (1855–1939) was the founder and headmistress of a Polish girls’ school in Kiev. See https://www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl/a/biografia/waclawa-peretjatkowiczowa.

- POW, Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, the Polish Military Organisation, operating clandestinely on Russian territory in 1914–1921, made a major contribution to the efforts for the restoration of Polish independence.

- Poland was restored as an independent state in 1918 at the end of World War I, but its borders were not demarcated, which led to a series of wars with neighbouring states. The dispute with Germany over its western border led to three Polish Uprisings for Silesia (1919–1921) and a plebiscite for Upper Silesia, held in 1921 under the auspices of an international commission.

- Dr Bronisław Hager (1890–1969), a Polish physician from Upper Silesia who took an active part in the region’s pro-Polish independence movement. See http://www.montes.pl/Montes_4/montes_nr_04_06.htm.

- Wiktor Przepełski (1891–1941), combatant and one of the main figures in the Silesian Uprisings.

- The Polish text gives the name “Cimurska”, which looks like a misprint.

- Halina Sołowijowa-Wojciechowska is on the list of Silesian Insurgents, and described as a courier and medical orderly serving in the Uprisings. See Encyklopedia powstań śląskich, Franciszek Hawranek et al. (eds.), Opole: Instytut Śląski, 1982, p. 611. Adam Rząsa, “Nauczycielka–powstaniec śląski z Rzeszowa. Sylwetki. Halina Wojciechowska-Sołowij.” Also Za Wolnośći Lud, 1984, no. 13, p.7.

- Michał Tadeusz Grażyński (nom-de-guerre Borelowski, 1890-1965). A major figure in the Silesian Uprisings and later Voivode of Silesia. See https://slaskie.naszemiasto.pl/michal-grazynski-kontrowersyjny-wojewoda-slaski/ar/c1-3015086.

- Antonina Rokicka-Niedbalska (1893–1975), a Silesian insurgent. See https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonina_Rokicka-Niedbalska and http://www.polskaniezwykla.pl/web/place/people,2523.html.

- Bożena Sołtys-Schayer (1895-1985), a Silesian insurgent. See Czesława Mykita-Gleńsk, “Córka Heleny i Joachima — Bożena Sołtys-Schayer,” Śląskie Miscellanea, 13(2000): 97-107. http://sbc.org.pl/Content/88158/ii499767-13.pdf and https://www.pilsudski.org/pl/zbiory-instytutu?catid=0&id=384.

- Sicherka, abbreviation derived from German Sicherheitspolizei, viz. the local (German) security police station. Cf. https://dzieje.pl/aktualnosci/iii-powstanie-slaskie.

- Alfred Kolszewski, 1885–?, Silesian insurgent. See http://mobi.nowiny.rybnik.pl/artykul,38202,koszty-trzeciego-zrywu; Krzysztof Brożek, Polska służba medyczna w powstaniach śląskich i plebiscycie, Instytut Śląski w Opolu: Wydawnictwo Śląsk, 1972, p. 89, 116, 134, 195, 237, 247, 271, and 324; and the same author’s article, “Kolszewski Alfred Antoni, pseud. Wilczek (1885-1944) — lekarz, uczestnik powstań wielkopolskiego, śląskiego i warszawskiego,” Śląski słownik biograficzny, Vol. 3. Jan Kantyka and Władysław Zieliński (eds.), Katowice: Śląski Instytut Naukowy, 1981 p. 158–159, http://www.gbl.home.pl/gbl/oddzialy/gbl_katowice4.pdf.

- “W dziesięciolecie,” Dla Przyszłości. 5(1931), published by Organizacja Przysposobienia Kobiet do Obrony Kraju (Warsaw).

- Before the Second World War Lwów was on Polish territory. It is now known as Lviv and belongs to Ukraine.

- Związek Pracy Obywatelskiej Kobiet.

- Ochotnicza Legia Kobiet.

- A type of children’s outdoor playground devised by Dr Henryk Jordan (1842–1907), professor of gynaecology and obstetrics at the Jagiellonian University, Kraków. The first park of this kind was founded in 1889 in Kraków.

- The equivalent of a ministry of education.

- Pomocnicza Służba Wojskowa.

- Kompania Obrony Lublina.

- Wojskowa Służba Kobiet.

- SZP—Służba Zwycięstwu Polski; ZWZ—Związek Walki Zbrojnej, AK—Armia Krajowa (respectively: Service for Poland’s Victory, Union of Armed Struggle, Home Army)—the names of successive Polish resistance organisations.

- Campolon—a German drug for the treatment of pernicious anaemia, put on the market by Bayer AG in the early 1930s. See https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?cmd=Search&term=Campolon.

- Department 2—intelligence and counterintelligence.

- Volksdeutsche—persons with “German roots”, who were more privileged than non-Germans.

- Now Gomel, Belarus.

- See the biography of Katarzyna Łaniewska on this website.

- German for “diarrhoea.”

- German for “sick bay” or “infirmary,” used in the concentration camps for the prisoners’ hospitals.

- German for “Mummy.”

- Presumably an ex-servicewoman from Piłsudski’s Polish Legions during World War I.

- Zugang—German for “new arrival.” Muselmann (German for “Moslem”)—concentration camp term for an extremely emaciated prisoner on the verge of death. See Teetering on the brink between life and death: A study on the concentration camp Muselmann.

- Inmates of Nazi German concentration camps had to wear a badge on their prison gear. The shape, colour, and lettering on the badge classified them, for example, Jewish inmates wore a yellow Star of David, Polish “political” prisoners had a red triangle with the letter P, etc.

- In Auschwitz a prisoner’s daily food ration consisted of 300 grams of brown bread for supper, a bowl of “soup” with an unpleasant taste at midday, and a cup of ersatz coffee or herb tea for breakfast. The nutritional value of this diet was very low. See an article on the concentration camp diet on the Auschwitz Memorial website.

- In the Auschwitz jargon “to organise” meant to procure something by illegal or illicit means (i.e. to steal).

- Der Arzt kommt!

- The Warsaw Uprising of the summer of 1944, not to be confused with the Ghetto Uprising of April 1943.

- The English version of Dr Białówna’s biography is due to be published soon on this website.

- Zulage—German for “extra” or “perk,” meaning the small slice of sausage or minute portion of jam patients of the prisoners’ hospital sometimes received with their bread ration.

- German for chief nurse or matron.

- A sub-camp of Flossenbürg was located at Plauen (Saxony), and comprised three divisions located on different sites. See https://www.wikiwand.com/de/Liste_der_Außenlager_des_KZ_Flossenbürg or https://www.slpb.de/fileadmin/media/OnlineWissen/Dossier/NS-Terror_in_Sachsen/Anhang_C_-_KZ-Aussenlager_in_Sachsen.pdf.

- In late 1944 and early 1945 the Polish Armoured Division commanded by General Stanisław Maczek liberated Belgium and Holland from German occupation.

- Most probably the hospital now known as the Countess of Chester Hospital. See https://www.coch.nhs.uk/.

- Presumably either the hospital now (2020) known as Glanrhyd Hospital, or Parc Gwyllt Hospital.

- A now disused name for the status of a new medical graduate in UK hospitals (now known as a foundation doctor, equivalent to a medical intern in other countries).

- Komitet Opieki Społecznej w Konstancinie.

- Krzyż Niepodległości.

- Śląska Wstęga Waleczności i Zasługi I klasy.

- Srebrny Krzyż Zasługi.

- Order Wojenny Virtuti Militari V klasy.

- Medal Wojska.

- General Jerzy Ziętek (1901-1985) was a combatant in the Silesian Uprisings. During World War II he was deported to the Soviet Union and on his return to Poland was a member of the Communist authorities of the Silesian region.

- In Poland St. Barbara’s Day, 4 December, is the traditional holiday of the country’s miners, celebrated especially in Silesia.

- Koło Weteranów Powstań Śląskich w Zabrzu.

- Szpital Praski.

Notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator in the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

I have written this article on Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa on the basis of the following sources:

- Dr Baraniecka-Szaynokowa’s handwritten CV (the original document is owned by her daughter, Halina Szaynok-Szwykowska).

- Dr Baraniecka-Szaynokowa’s personal documents, including her graduation certificate for the medical degree (1925; owned by her daughter).

- Dr Baraniecka-Szaynokowa’s notes and recollections (owned by her daughter).

- Publications

- Krzysztof Brożek, Polska służba zdrowia w powstaniach śląskich i plebiscycie, Instytut Śląski: Wydawnictwo Śląsk, 1973;

- rhe 1929–1939 volumes of the monthly magazine Dla przysłości.

- Letter from the Director of the Auschwitz Museum to Dr S. Kłodziński, confirming that the Museum’s records hold an entry for Halina Sobolewska, Prisoner No. 64267.

- Extensive information from Halina Szaynok-Szwykowska.

- Letter of 14 June 1978 from Auschwitz-Birkenau and Ravensbrück survivor Dr Irena Białówna to Dr S. Klodziński.

- Data from Kazimiera Olszewska of Warsaw, collected by the committee on the history of women in the struggle for Polish independence affiliated to Towarzystwo Miłośników Historii w Warszawie (The Warsaw Society of the Friends of History) and other social organisations.

- My personal memories of Dr Szaynokowa, 1935–1971.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.