Author

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English.

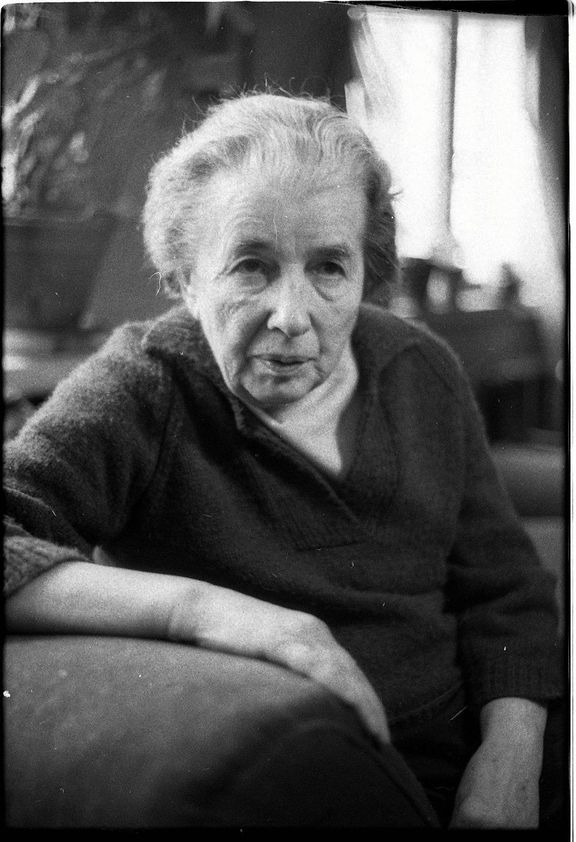

This doctor rendered distinguished and dedicated service to patients, especially children, and proved her mettle when the Nazi Germans imprisoned her and subsequently sent her to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Her name appears in many publications on the history of the women prisoners’ hospital in Birkenau, where she did a lot to improve its miserable standard of treatment. Under these conditions Dr Irena Białówna proved a tower of strength, undaunted, full of courage, goodness, and the ability to cope with little or no resources. Many survivors owe their lives to her. She was admired and regarded as a great authority not only by women who survived Auschwitz-Birkenau, but also by the people of Białystok, the city in which she practised as a physician for the rest of her working life after liberation.

Dr Białówna most certainly deserves to have her biography written up as fully as possible, with special attention to her wartime experience and work in the Nazi German prisons and concentration camps in occupied Poland. To keep this biographical article from reducing down to a mere catalogue of points in a dreary, soulless, official CV, I shall start by outlining the background to her life.

Irena Białówna was born on 3 November 1900 in Volgograd (USSR),1 then known as Tsaritsyn, in the family of Józef Biały, a railway engineer, and his wife Kazimiera née Kobylińska. Both of Irena’s parents were the children of physicians. She was one of the couple’s five children. Dr Jan Kobyliński, her maternal grandfather, a graduate of the Warsaw Principal College,2 was deported to Simbirsk3 (Russia) for treating wounded Polish insurgents in the 1863 Uprising.4

Irena’s sister Janina Krzyżanowska writes in an extensive letter to me dated 11 April 1982:

When our family was still living in Russia [under the tsars—S. K.] we observed the Polish traditions. Our house offered hospitality to many Polish people who were working in Russia. During the First World War our mother was head of the Polish committee for aid to refugees evacuated from Poland. She set up a Polish children’s home and school. We attended Russian secondary schools, but we also spoke fluent Polish and were familiar with Polish history and literature.

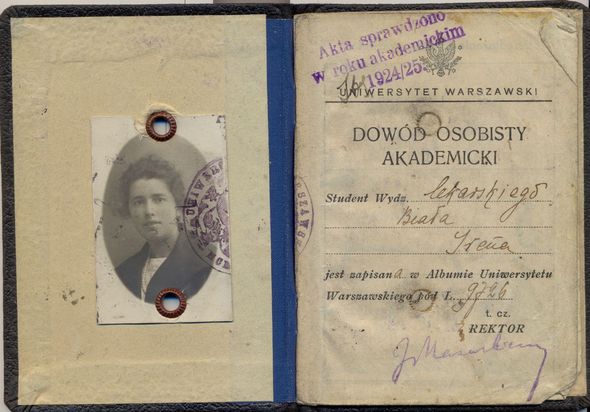

In 1918 Irena finished her grammar school education in Yelets, which was in the Gubernya of Orlov at the time, and is now in the Oblast of Lipetsk. After leaving school, she worked as a kindergarten teacher until 1920. By this time she was already committed to childcare. In 1920 she went up to Voronezh University for Medicine, and in August of the following year the family left Russia for Warsaw, where Irena continued her medical studies in the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Warsaw. When she was in her fourth year she was president of the students’ paediatric society attached to the children’s clinic directed by Professor Mieczysław Michałowicz. Irena Białówna graduated on 20 June 1927 and in September of the same year started out on her career in paediatric practice in the city of Białystok.5

For the first three years after graduation she worked as a volunteer6 in St. Roche’s Hospital (the municipal hospital of Białystok), at the same time engaged as a school doctor in several local educational and childcare institutions. She enhanced her professional qualifications in the Children’s Clinic of the University of Warsaw, under the supervision of Prof. Michałowicz, who was one of the pioneers of Polish paediatrics. She also engaged in social work on a voluntary basis on behalf of the Polish Red Cross and the Women’s Military Training Organisation.7 On 1 January 1939 she took up an appointment as a paediatrician for the Białystok branch of the Social Insurance Institution.8

Dr Białówna had already been called up for military service by the time the War broke out. She was in charge of the sanitary station serving the LOPP anti-aircraft defence unit, but was forced to disband the unit after five days due to a staff shortage. On 8 September 1939 the head of the surgery ward at St. Roche’s Hospital asked her to join the medical team attending to casualties. Her assistance was indispensable due to the fact that many of the junior doctors had been called up, while there was a large influx of patients and wounded soldiers following the evacuation of the local military hospital. Dr Białówna gave her full commitment to her work standing in for the ward physician of the infectious diseases ward, who was in the army. She also worked in a local children’s clinic. In late September 1939 when the German forces occupying Białystok retreated from the city, she resumed her former job as chief physician of children’s ward in the Paediatric Division of the Second Białystok Municipal Polyclinic.9

On 26 June 1941, after five days of combat in the border zone following Nazi Germany’s invasion of the USSR, the Wehrmacht entered Białystok. At the time Dr Białówna was again tending to the wounded and sick, and even performing nursing duties because she had allowed two of her nurses who were Jewish to retreat with the Red Army to save them from Nazi German repressions. In addition, she was also working as a physician in a TB hospital in the vicinity of the Polyclinic.

On 15 July 1941 the Germans closed down the Białystok outpatient services for children, and Dr Białówna was transferred to the children’s ward in the municipal hospital on ul. Fabryczna. On 26 July, when a ghetto was set up in this part of town, the ward was moved to a facility at ul. Warszawska 15, and Dr Białówna continued to work there until 12 March 1942, the day on which she was arrested. Her sister Janina Krzyżanowska writes in her letter that Irena was a member of the Polish ZWZ-AK10 resistance movement, serving as treasurer and quartermaster of the local AK unit, and organiser of the medical team of the local Women’s Military Forces.11 She took the AK oath in late July 1941.

Dr Białówna’s ZWZ nom-de-guerre was Bronka. Her immediate superior was the chief quartermaster for the Białystok unit. She was ordered to make direct contact only with headquarters, and for contact with the organisation’s outside delegates visiting the area to avail herself of the services of liaison girls using passwords that changed over time. Her familiarity with the topography of the city and its environs, and the fact that she knew a lot of local people predisposed her to find hideaways for liaison men and officers who came in from outside, and facilities where meetings could be held safely. Another of her duties was to keep the HQ’s correspondence and blank forms issued by authorities such as the Social Insurance Institution, road services, etc. These forms were to be ready to be filled in, for use whenever needed on orders from the local commanding officer.

In September 1941 the Central Board of the Polish Red Cross offered Dr Białówna the job of managing its Białystok branch. Her superiors in the ZWZ gave their approval, and she accepted the offer, which was communicated to her by the secretary of the Białystok branch of the Polish Red Cross. Her task was to provide financial aid for the dependants of ZWZ combatants who were away on duty. The Polish Red Cross permitted her to allocate part of these funds for the purchase of extra food for the children in the home for babies and infants attached to the hospital, as she later wrote in one of her CVs. These children had been lost along the roads by refugee families evacuating from combat areas, and had not been claimed by their parents for several months.

For some time the Gestapo had been sleuthing underground resistance activities in the area. In December 1941 Dr Białówna was warned by the secretary of the Polish Red Cross treatment centre that the organisation’s courier who used to bring funds from Warsaw was under surveillance. Dr Białówna notified the Central Board of the Red Cross, asking for them to withdraw this courier’s services. It was not until later, when she was in prison, that she learned that this girl was also liaising for a secret organisation known as Szaniec (Barricade).12 However, in February 1942 the girl brought another cache of money and insisted that the allegations concerning her had been disproved. She arrived again on 10 March. Dr Białówna and her trusted co-workers promptly distributed the money to the soldiers’ families in receipt of the welfare and handed over the sum set aside for the children to one of the carers in the children’s home. Without further ado, she completed all of her duties, just in time as it turned out, because on 12 March the Gestapo arrested her from her home and put her in prison.

Her imprisonment put a stop not only to her intensive professional work, but also to her activity in the resistance movement; however, I should add, not for the entire period of her confinement, since, as we shall see, even when she was in prison and concentration camps she was able to provide medical care and save lives, and also to engage in clandestine activities, regardless of the risk of reprisals or even death.

Irena Białówna’s academic ID. Source: Ciesielska, M. Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942–1945), 2015. Click the image to enlarge.

First she was held for six months in the Nazi German police and Sipo13 prison at No. 15 on the street then known as Erich-Kochstrasse (now ul. Sienkiewicza) in Białystok. This jail was overcrowded all the time, but for her first month there she was kept in solitary confinement. She was not interrogated until after two months, so she had plenty of time to collect information on her case before the interrogations started. She learned that her discovery was the outcome of the arrest of the Red Cross courier who also liaised for Szaniec. Thanks to sporadic contacts with other prisoners and wardens’ conversations she happened to overhear, she gathered that none of the people she knew were in the prison, except for a nurse, the supply manageress and the former secretary of the Red Cross Hospital. This made it easier for Dr Białówna to devise a line of defence for the difficult interrogations ahead. Perhaps she might have been released had it not been for the disclosure of some of the members of the ZWZ resistance group in Białystok.

The next four months of her imprisonment were easier. She and the nurse were assigned the job of keeping the prison tidy, cooking, and washing prisoners’ laundry. That was when she discovered an opportunity to acquire extra food to supplement prisoners’ starvation rations. She was assisted in this venture by a Jewish man known to her only by his nickname Michał. He came in from the ghetto for work in the piggery.

Now relatively free to move about the prison and its yard, around the end of August 1942 she saw one of the prisoners commit suicide. He was in chains, but managed to swallow a poison pill. He was one of the members of the ZWZ group, dozens of whom were arrested after the Gestapo extracted information from a liaison boy they had caught. The man who committed suicide was his friend, and most of the other detainees were later shot. After a few weeks she saw some of her pre-war acquaintances in the prison yard, but had no chance to talk to them. She learned that on 5 September a group of around a dozen young prisoners, including two women, had been taken to a place called Jeziorko near Łomża and shot. She got this information a few weeks after the incident, after her transfer to another prison.

On 25 September 1942 she was moved to the prison under the authority of the SD14 and security police chief in Białystok. This jail was located in the building of the pre-war prison on ul. Kopernika. There she learned from Ginterówna, a girl from the ZWZ’s municipal HQ for Białystok, that during a house search the Gestapo had landed on the ZWZ’s archive and found a warning note advising members to cease contacts with Dr Białówna following her arrest. So she realised that although she had got through the investigation against her fairly well, her situation now was much worse and she could be interrogated and tortured any day. What saved her was an epidemic of typhus raging in the prison. Even the governor had gone down with it, but when she cured him, he was so grateful that he offered her a job in the prison hospital. Typhus made the Germans panic-stricken, and that is why he was so considerate to her. In the circumstances the investigation against her was brushed aside.

As she was attending typhus patients, Dr Białówna was able to get dinners, cigarettes, and medical handbooks brought in from outside. The prison hospital was run unofficially by a Jewish doctor who was brought in from the ghetto for a few hours every day. He was going through a mental breakdown and was scared of coming into contact with patients who were dirty and lice-ridden. Dr Białówna was shocked at the state of the hospital. Its walls were peppered with bullet holes, as the previous group of prisoners with typhus had simply been shot. The manager of the hospital, a prisoner serving a sentence for criminal offences, ordered patients who were barely able to stand up on their feet to attend to the bedridden. There was only one nurse, another prisoner, and she had already contracted the disease herself.

As Dr Białówna noted in one of her unpublished CVs, in that hospital she had no medications at her disposal except for a handful of digitalis leaves. She had no one to help her, since even the doctor contracted typhus and died. But she did not give in; she proved her resourcefulness and ingenuity. First she managed to get the criminal replaced by a young prisoner who was a railwayman, and find two women prisoners to work as orderlies. She also managed to isolate off the typhus ward. In a biographical account she wrote,

Gradually I managed to persuade the governor of the prison that it was absolutely necessary to isolate the hospital off. The entrance to the hospital was double-locked, on the outside by the guards, and by me on the inside. So there was always a brief spell between the time when the bell rang and the time it took me to get to the door, which let me keep my cool and calmly relocate patients, not only in accordance with the seriousness of their condition, but also with the need to keep them in hospital for a longer period.

We got permission to have dinners brought in from town for the patients, and the privilege was extended to apply to some of the prisoners in the cells. The governor allowed the families of prisoners to send in medicine on individual prescriptions. My patients had no change of underwear or bed linen, so the families were allowed to send in blankets and underwear, but on condition that they would not be able to reclaim them. Some of the families did not agree to this. We were also allowed to start an outpatient service in the prison building and doctor’s visits to patients in their cells. This gave us the opportunity not only to provide medical treatment for them, but also to establish the right sort of contact with inmates.

At this time the prison was considered to be on the verge of an outbreak of an epidemic. There was no torture in this prison, so we did not have any patients who had sustained injuries during interrogations. Some people even regarded staying in the prison hospital as a kind of respite.

I should add an aside to this interesting description of the hospital in a Białystok jail. The following year there was indeed a typhus epidemic, due to the bad sanitary conditions. The typhus epidemic along with other contagious diseases caused the death of thousands of prisoners.

As we see, Dr Białówna encountered disastrous sanitary problems when she was held in prison. The experience of coming to grips with them served her well later, when she was a concentration camp inmate of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Gross-Rosen, Ravensbrück, and Neubrandenburg.

She would soon be sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Meanwhile, in late October 1942, after five weeks of working in the typhus ward of the prison hospital, she went down with the disease herself. It took a particularly severe course. She was ill for two months. At first, there was no one to attend her at all. Luckily, after a few weeks the nurse who had been sick returned to work, and later there was also a male prisoner who had been an army paramedic.

At this time the prison regime became much more stringent. This was because one of the guards had released a group of prisoners from the Gestapo jail and shot a German office he happened to meet. 25 political prisoners were shot in retaliation. Given this situation, after she had recovered from typhus, Dr Białówna did not return to work in the prison hospital, in any case she was still very weak, and in late December she developed an unspecified and untreated neurological infection, which put her out of action for a further two months.

Since November 1942 she and a group of five other women prisoners had been due fir deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau, which had become a widely known establishment by that time. The decision had been taken by the Gestapo, but its execution was postponed, first by her illness, and subsequently by the clever assistance she was given by fellow-prisoners taking advantage of the fact that she was so exhausted after her illness. The women due to be deported with her were sent off in December 1942, while she herself did not reach Auschwitz-Birkenau until 26 April 1943, on a roundabout route via prisons in Königsberg, Warsaw, Katowice, and Kraków. On arrival she was registered as political prisoner No. 43117.

As she writes in a 1979 account of the history of the prisoners’ hospital in Birkenau,15 she was sent to work in the prisoners’ hospital straight after the sauna, when she declared that she was a doctor. She was told to report to the admissions room in the afternoon. She had received verbal abuse in quarantine and in the sauna, but as soon as she got to the hospital admissions room she was given a courteous welcome by Monika Galicyna and Helena Matheisel, the Polish secretaries working there. She spent the next two days in Block 23, purportedly staying there as a patient in a very serious condition. On the following day she went to Block 24 to help Dr Janina Kowalczykowa.

As we learn from Danuta Czech’s Auschwitz Chronicle,16 at the time there was a small transport of 18 male and 47 female prisoners (Nos. 118870–118887 and 43075–43121 respectively) in the block. Selections and the mass extermination of large transports in the gas chambers had been going on for some time already, at this point chiefly involving Greek Jews. The Roma family camp was in operation, and SS physicians were performing criminal experiments, mostly in Block 10. The underground resistance movement in the camp was conducting its secret operations, sending reports to their outside contact centres, usually to Kraków, and organising successful escapes.

Dr Białówna thought it was better for her to arrive in Auschwitz in the spring rather than, say, in the winter, because it was easier to adjust to the inhospitable conditions in the camp when it was getting warmer outside. She had already been through typhus, so she had developed immunity to the disease, epidemics of which were rife in the camp and very dangerous for prisoners. Dr Białówna was sent to work as a physician in Block 24, the diarrhoea ward of the Birkenau prisoners’ hospital, replacing Dr Kowalczykowa, who was transferred to Auschwitz I. In her new job Dr Białówna met fellow-prisoners who were helpful and ready to undertake the challenge of working with a large number of very sick and dying patients. She described the situation in the block in an article published in the 19th edition of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (p. 164–175).17 For just a fortnight in October 1943 she was working in paediatrics, her favourite branch of medicine, in the children’s ward in Block 16, looking after children sent to Auschwitz from places like Vitebsk.18 Of course, these hospitals and the work in them were nothing like the normal conditions in hospitals.

In one of her letters to me (dated 14 August 1974), Dr Białówna made some important and original observations on the fate of the child prisoners of Birkenau—a research issue that has not been fully examined yet. The predicament of these children shocked her and made a deep impression on her memory. She managed to hide some of these children in Block 24 and save their lives. Her letter is a very important record, so let me quote a long passage from it:

At the time of my arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau in April 1943 there were no children in sectors B IIa and IIb. The Jewish children were with their mothers in the camp for new arrivals from Theresienstadt and in the Roma family camp on the other side of the ramp. All of those children were killed along with their parents. Children from the Zamość region19 of Poland and from Belarus—and perhaps from other parts of the USSR as well—did not start to arrive in our part of the camp until the early autumn of 1943, and in greater numbers in 1944. The ones who arrived in the autumn of 1944 came with the women deported from the Warsaw20 Uprising.

As the influx of children grew, a block was set up to accommodate them, followed by another children’s block. Conditions in these blocks in respect of bed linen and equipment, washing and feeding the children were no different than in the blocks for adults, though of course children are far less able to fend for themselves than adults. I don’t remember whether the babies who were breast-fed by their mothers stayed with their mothers in these blocks after leaving the hospital, or whether they were sent to blocks for adults. The mothers of older children tried to keep in touch with them, but it was not always possible.

Women prisoners tried to help these children in a variety of ways. The children’s blocks were virtually inaccessible to the hospital staff, who were only allowed in to see a child if it was sick. We tried to give a few of these children a fictitious job in the hospital, but in most cases this depended on the good will of the block senior. We managed to give a few children the possibility of getting better food and sleeping conditions. To give an example, I’ll mention Haneczka Wróblewska, aged four,21 who was in our block and whom the secretary’s office helped to “employ” as a messenger. Haneczka had arrived in Auschwitz in a trainload of women deported from Warsaw in the aftermath of the Uprising. When the women were being made to board the train she was separated from her auntie and granny, who were looking after her, and put on the train. She spent the journey in the care of strangers. I met her by chance on the premises of the hospital, after she had run away from the children’s block to look for the lady who had looked after her on the train.

Sick children came with their mothers to outpatients, and in late 1943 they had 24 two-storey children’s bunks reserved for them in a section of Block 16 and separated off from the rest of the building. On orders from the camp’s management, women prisoners painted pretty little tableaux from children’s stories on the walls and beds. Höss22 used to come in to admire the conditions in the children’s ward; however, its equipment and resources were poor. The beds were fitted out with new, warm blankets, but a very small amount of bed linen and nappies. The children had a small extra amount of milk, milk soup, and kissel.23 Other than that, their food was no different than the ordinary ration prescribed for adults. Moreover, the staff, maybe more numerous than in the rest of the blocks, were not professional health workers, a considerable number of them selected on a preferential basis for individuals who wanted an easier job than work out of doors. I remember and am full of admiration for Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa,24 who worked in the children’s ward. In the camp she used a false name, Sobolewska, and had been arrested in Kiev for her involvement as a liaison officer.25 Dr Baraniecka-Szaynokowa kept quiet that she was a qualified physician and worked as an orderly. She was an invaluable caregiver for the children; unfortunately, after a short time she was sent to another camp.

The supply of medications was next to nothing; for the most part we had to avail ourselves of all the usual methods practised in the camp to get medicines. The most common illnesses were serious cases of pneumonia and diarrhoea; patients with infectious diseases were put in the general infectious block. As the number of sick children was rising, they had to share a hospital bunk with several other children. Many of the mothers did not trust the caregivers and tried to keep their children. As a result some children came to us when they were on the verge of death. Children were so ill and the conditions in the ward so bad that mortality was very high. At first, the overwhelming majority of the children in the ward were Belarusian; later there were Polish children as well. I was the first doctor to work in the children’s ward; a few months later a Russian doctor, Olga Nikitichna, was sent to work in the block. She was a paediatrician from Kiev (I don’t remember her surname).26 At first, there were the two of us; later I was transferred back to the diarrhoea block. The separate children’s ward was closed down when the Russian doctor left; I don’t remember when exactly it happened; subsequently Dr Janina Kościuszkowa looked after the children in Block 22. . . .

Birkenau survivor Janina Komenda (now deceased) wrote in the unpublished passages of her recollections that when the notorious SS physician Dr Mengele was conducting his experiments, chiefly on children, including twins, sometimes he would send his victims to Dr Białówna, telling her to treat them using the best medications, which he provided.

I should explain that of the two sectors of Birkenau I have mentioned above, B IIa was left of the ramp at the end of the railway line, sectors c, d, etc. were to the right of the ramp. Dr Białówna made a sketch of how the Birkenau prisoners’ hospital evolved. According to her diagram, there were several rows of barracks on the left hand side of the end of the railway line, at a right angle to it. Blocks 28, 29, and 30 were to the right of the entrance to sector B IIa between the road and the railway line; Blocks 22, 23, and 24 were in the next row, and until the spring of 1943 made up the women’s hospital. The third row comprised Blocks 16, 17, and 18, which were added to the hospital by the autumn of 1943. Finally, in 1944 a fourth row was added, with Blocks 10, 11, and 12; and a fifth row (Blocks 4, 5, and 6). Dr Białówna wrote that she worked in Blocks 24 and 16.

Later she and the patients of Block 24 were moved to other hospital blocks. Moves were carried out allegedly in connection with insect control or the redecoration or overhaul of the block, changes in the hospital structure, and they were always a nuisance for the patients and the prisoner medical staff. The moves were done at a breakneck speed and in a primitive way with no safeguards for the welfare of the patients, exposing them to the cold and putting them at risk of shock or even death. During such moves Dr Białówna usually lost some of the prisoners she had befriended and trained to work as medical staff. However, she always managed to resolve the problem, as she was full of energy and very resourceful, and soon her new block was busy carrying out its tasks.

Block 24, where it was Dr Białówna’s lot to work, was managed by the notorious Schwester Klara, a green triangle27 who was a midwife by profession convicted for murder and infanticide. She didn’t care at all what happened to patients and stole their belongings. Block 24 was one of the worst hospital blocks, especially as regards its dreadful sanitary facilities. It was ravaged by selections, but even in such hopeless conditions Dr Białówna bravely risked her own life trying various ploys to save women selected for death. On three occasions she was successful and managed to save some of the women listed for extermination.

One of the prisoners who was a patient and spent quite a long time in Dr Białówna’s block said the following about her:

Dr Irena Białówna from Białystok, a Polish woman prisoner, was the permanent doctor in Block 24. I remember her slim figure in striped prison gear and her benevolent, charming smile which earned our trust. Dr Białówna had practically no medicines at her disposal, but she used to clamber up to the top bunks and patiently listen to our moans and groans. Her very presence, the compassionate care and words of comfort she gave us, and her sympathetic attitude had a soothing effect on sick prisoners.

That is a typical opinion of this brave doctor.

Dr Białówna stood out among her fellow-prisoners in the hospital blocks for her authority, conduct, level-headedness, calmness, and courage. She was the leading figure among the Polish prisoner-doctors, who made up a sizeable group; and she had a good effect on the fate of large numbers of women patients. She worked, and often shared living quarters with many other women prisoner-doctors, such as Katarzyna Łaniewska, Alina Tetmajerowa, Celina Choynacka, Jadwiga Hewelke, Jadwiga Jasielska, Władysława Jasińska, Ernestyna Michalikowa, Wanda Starkowska, Zofia Kączkowska, Janina Kościuszkowa, and the Austrian Ella Lingens. I should add that even the SS doctors had a certain respect for Dr Białówna and sometimes recognised her professionalism and the efforts which she never spared to help patients.

After the War she did not forget her fellow-prisoners, both those who were and those who were not doctors, and kept in touch, meeting with them and writing letters. She was of service, helping them with her advice and kind words, as may be seen in correspondence and a variety of publications on concentration camps. She herself made numerous comments and provided materials for such articles, especially biographical ones published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. She could write stirring character studies of her medical colleagues, for instance of Dr Ernestyna Michalikowa, who died in Birkenau (this biographical note has not been published yet).

There are many mentions of Dr Białówna in publications on concentration camps. In the manuscripts she is highly commended by Janina Komenda, a fellow-inmate of Birkenau (No. 27233) I have cited above. She spent almost the entire period of her imprisonment in Birkenau in the women’s hospital, chiefly in the block Dr Białówna looked after, and in the unpublished part of her recollections she writes the following:

Dr Białówna was the heart and soul not just of our block, but of the entire prisoners’ hospital. She never refused help to those in need in other workforce or quarantine blocks. Countless times on a dark, cold or wet night after the roll call, she would be making her way in the thick mud with injections or medicines to other blocks. Dr Białówna never raised her voice; she was never impatient or angry; always calm and with a smile on her face, she would ask politely when in fact she should have been issuing orders.

Under her influence, the atmosphere in the block slowly started to change. The swearing and name-calling that used to occur in the morning petered out, the staff on duty in the block started to work better and more diligently, and the block senior took better care of the block. Thanks to Dr Białówna we managed to get more blankets, a change of mattresses, and even sheets; and there were fewer and fewer patients with no nightshirt. Dr Białówna enhanced the stock of medications; she acquired needles and syringes for injections. Thanks to her efforts after some time our diarrhoea block, which used to be regarded as the worst and dirtiest, became the model block, and even the Germans were impressed because it was so clean and the care patients received struck the eye.

Not only did our block’s outer appearance change under the influence of Dr Białówna; there was also a fundamental inner transformation in human relations. By early 1944 things that patients had never managed to obtain before, not even for money, became the normal, matter-of-course situation. Every day patients were washed, each one had a clean basin of water to herself; they had their hair combed and their nightshirts and bed linen laundered by the cleaners. In addition they were seen by the doctor every day, and given the best nursing care and medical treatment possible with the resources available.

The figures show the importance of the changes Dr Białówna introduced, notwithstanding the short supply of the resources. In the winter of 1943/44 the death rate in the block was about 50 per day, whereas in the winter of 1944/45 there were days when no one died, with over 300 patients in the block.

Dr Białówna worked indefatigably. Every day she admitted dozens of new patients and examined them all meticulously. In addition, she examined all the bedbound patients, administered injections and changed dressings herself, assisted in these duties first by Olga Śmieszkiewicz and later by Helenka Niesołówska. Her work was not easy—there were ulcers, phlegmons, burns, cases of frostbite, and wounds due to vitamin deficiency, dreadful bedsores, and oozing abscesses that needed treatment . . . as well as conditions caused by tuberculosis and other diseases, which called for a lot of effort and self-sacrifice when dressings had to be changed. . . .

Dr Białówna always had a lot of inmates “on her conscience” after they had recovered but still needed to be kept in hospital. She had the ability to quickly gauge the situation, imperceptibly order the staff to remove their medical cards and get the patients involved out of the SS doctor’s sight.28

It needs to be said that at this time the SS doctors for the women prisoners’ hospital in Birkenau were Werner Rohde, Fritz Klein, Hans Wilhelm König, and Joseph Mengele, and for a short time Heinz Thilo. The Luftwaffe physician Horst Schumann was already carrying out his experiments. So a strong and select gang of criminals, absolute lords of the life and death of masses of victims had gathered in the women’s hospital, making it all the more difficult for the prisoner staff to work and continue their secret operations.

Dr Białówna resorted to the most elaborate measures to look after the children and save their lives. For instance, she managed not only to “employ” six-year-old Haneczka Wróblewska,29 a prisoner who had arrived from Warsaw in the aftermath of the Uprising, with no one from her family to look after her, but also—with the help of other women—to save her life during the Death March evacuation of the camp on the night of 17/18 January 1945.

Dr Białówna was fully dedicated to her women patients and tried to provide them with a stand-in programme of cultural events to get their minds off the hopelessness and grim reality of Birkenau. She did not distance herself off from her patients but joined in their life in the block, supporting all their events, such as anniversaries, name-days,30 etc., which were to remind them of the traditions they had enjoyed when still free. At Christmas, when a prohibition was imposed on putting up a Christmas tree, Dr Białówna obtained a large Christmas crib for her patients. It was an elaborate cut-out made of paper, and she installed it over the stove, for all to see and enjoy.

As the front approached nearer and nearer from the east, the SS men in charge of Auschwitz-Birkenau hastily started to evacuate the camp. Various rumours went round, for instance that the children would be evacuated in a separate move to Łódź. Dr Białówna tried to stay with her patients. Meanwhile, the SS doctor ordered the transportation of her colleague A. Piotrowska,31 who had been her fellow-student at university. Dr Piotrowska had been rounded up in the aftermath of the Warsaw Uprising. She was using an “Aryan” ID document, but looked very Semitic. To protect her friend from impending danger, Dr Białówna volunteered to take Dr Piotrowska’s place for the transportation, and the SS physician allowed her to do so. Janina Komenda writes,

At noon [on Tuesday, 16 January 1945—S.K.] my friends and I escorted Dr Białówna to the gate. It was a fine, sunny though frosty day in January, which raised our hopes. Dr Białówna didn’t leave until the next day [in the evening]. We didn’t know that at the time, and as it turned out later, she attended the children, though they didn’t go to Łódź, but took quite a different direction for another destination.

In connection with this, in the account she wrote for J. Krętowski and F. Taraszkiewicz, Dr Białówna later recalled:

That journey was one of the most difficult ordeals in my life after my arrest. I reached Wrocław,32 with 35 children, including 5 babies in my care. The children were given no provisions for the journey, except for a tin of powdered baby milk. In Wrocław we boarded a slow passenger train for Łódź, which had already been liberated [by Soviet troops on 17 January 1945—S.K..

She continued her account with a description of how at one of the large stations on the way, the SS men guarding the train panicked and for a short while left the train unattended with the carriages open, but she could have hardly fled with all the children in a front-line area in the middle of combat.

They continued on the journey with many hardships on the way and on an empty stomach to Ostrów Wielkopolski, and from there turned back to Wrocław, and then spent a week in Gross-Rosen concentration camp. From there they spent a fortnight of travel in an unheated train in an unknown direction. The five babies died on the way. Finally, from Oranienburg station she and the surviving children walked to Sachsenhausen,33 which they reached during the night. The commandant drove them out of the camp, and they were put on another train. On 30 January 1945 they arrived at Ravensbrück concentration camp, where Russian women prisoners took over from her to look after the children. Dr Białówna was sent to Block 18, the prisoners’ hospital. In late March 1945 she was evacuated to Neubrandenburg,34 where she stayed until the end of April.

The conditions in Neubrandenburg were exceptionally hard and primitive. There was no SS doctor, so all the decisions concerning patients were taken by Schwester Lisa, a sadistic dilettante who made despotic pronouncements on who was to be admitted to the hospital, what kind of treatment was to be administered, and which patients were to be got rid of. Despite the obstacles, Dr Białówna managed to circumvent the official regime and admit some prisoners after the evening roll call, keeping them in the hospital at least for a few days as “emergencies.”

There was dreadful hunger. One loaf of bread had to be shared between ten prisoners, with a helping of stinking nettle soup. When the “healthy” prisoners were evacuated, Białówna stayed in the camp with the nurses and patients. There was no food at all, so the prisoners broke into the storage facility where it was kept and brought out food parcels for the patients. On the following day, Dr Białówna was able to speak (in the presence of SS men) to the representative of the Swedish Red Cross, who made a declaration that the women would be evacuated to Sweden.

On the same day she drew up a list of patients who were collected by several trucks and taken to the nearest port. Their departure was delayed because the drivers were tired and Allied bombing raids were going on. Eventually they sailed in a merchant ship from Lübeck for Trelleborg in Sweden. Once in Sweden, the patients were provided with sanitary care and the administrative formalities were done, after which the women were put up for a few days in one of the Swedish health resorts for a preliminary medical examination and allocation to hospitals or quarantine camps. Dr Białówna and her group were sent to a small village called Harplinge, where she spent three weeks in quarantine in the care of the local doctor, and finally had the opportunity to take a little rest.

After recuperating in Sweden, Dr Białówna parted with her companions, who found employment in factories or farms, and took a job in a TB sanatorium in Halmstad for women survivors of the Nazi German concentration camps. She worked there until 20 September 1945. She wanted to return to Poland as soon as possible and did not wait for officially arranged transportation. With money borrowed from a Swedish doctor she made friends with, she bought a ticket for the second flight on a new air route from Sweden to Poland, and was back in Warsaw on 25 September.

Now there was a period of intensive hard work ahead of her in the devastated hospital system of Białystok and its region. She devoted all her energy to looking after the health of children, adolescents, and mothers. She did not start a family. She achieved really impressive results, and her work was the foundation for the development of paediatrics in Białystok. She made a substantial contribution to the enhancement of public health and reducing infant mortality in the region, and especially to the improvement of the health system and the education and training of young health workers.

Krętowski and Taraszkiewicz write that as soon as Dr Białówna returned to Białystok in September 1945, the local education authority offered her an appointment as a school health inspector. The letter with the offer says she was to start already on 15 October. Soon she returned to work as a paediatrician, and made a distinguished contribution to this branch of medicine. In late 1952 she was appointed chief physician in a new children’s ward at the Jędrzej Śniadecki Hospital35 for the Voivodeship of Białystok; and in 1955 when the ward was transformed into the Paediatric Clinic36 of the Białystok Medical Academy, she took an adjunct professor’s appointment, which she held until the end of 1957. She also lectured on paediatrics in several nursing and obstetrics colleges.37 In April 1946 she was appointed voivodeship health consultant for mothers and children,38 and worked in this post until she retired in April 1979.

In his funeral oration for Dr Białówna, Franciszek Taraszkiewicz said that she pioneered a programme of postgraduate medical courses and took a particularly active part in their development. Thanks to her endeavours, in 1958 a state-run children’s home was founded for infants, as well as a social paediatrics and obstetrics training centre for doctors and nurses. This institution was generally referred to as “the Swedish house” because it was a gift from the Swedish children’s aid society. Dr Białówna had a profound appreciation of the importance of continual training in paediatrics, and attended further education and training courses herself, such as the one held in France by the International Paediatric Association from 5 November to 16 December 1956.

For many years she worked for a specialist healthcare team in Białystok for mothers, children, and adolescents,39 which was directed by Dr Franciszek Taraszkiewicz, head of the Children’s Clinic for Infectious Diseases at the Białystok Medical Academy.40 In February 1981 (i.e. when Dr Białówna was still alive) Dr Taraszkiewicz and Dr Józef Krętowski sent a short biography of her and a few passages from her memoirs to the editors of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Dr Białówna made use of every opportunity to provide and promote paediatric services. Thanks to her, infant mortality in the Białystok region went down very substantially.

Fully dedicated to aid for children, alongside her professional work she also engaged in social work and had a reputation for her exceptionally active contribution for this cause. In 1957 she was elected to Sejm.41 She was an active member of the Białystok branch of the Society for Informed Maternity.42 In 1961 she was appointed a member of the scientific council of the maternity hospital known as the Institute for the Mother and Child;43 and in the following year to a national paediatric advisory council for methodology and organisation and national consultancy; and to a committee for rural medicine attached to the scientific council of the Ministry of Health. In 1974 the honorary membership of the Polish Red Cross was conferred on Dr Białówna in recognition of her outstanding achievements. She was granted numerous other honours and distinctions, nevertheless all she was interested in was to be of service to children, and treated her popularity merely as an aid facilitating her paediatric work.

In a letter of 7 April 1953 to the Polish Ministry of Health, Professor Mieczysław Michałowicz proposed Dr Białówna’s extraordinary appointment to a professorship of paediatrics at the Białystok Medical Academy. He made the following observation:

Dr Irena Białówna has won the respect and admiration of the people of Białystok. Polish paediatricians regard her as one of the pillars of strength of the People’s Republic of Poland. . . . We consider her work in today’s preventive and clinical medicine in the field of childcare an achievement fully equivalent to the required number of scientific publications.44

And indeed, Dr Białówna’s vast and very productive work in medicine definitely brought results that were far more important than many a scientific paper on the medical sciences. The inestimable assistance and dedication she devoted to her patients in the prisons and concentration camps, and her post-war services on behalf of war veterans defy rule and measure.

Dr Białówna made a lasting impression on the memories of those she helped during the War. Here is an example. Taraszkiewicz recalls that around 1970 Dr Białówna received a visit from a Soviet citizen who had survived Birkenau and wanted to show that she remembered Dr Białówna’s kindness and to express her gratitude in person. This Russian woman had given birth to a little girl on the journey to Birkenau. When she reached the camp there was no food, water, or clothing for her and the baby, so she was just waiting to die. She saw Dr Białówna approaching and thought she was a German functionary, so she wanted her to let them die as quickly as possible. Dr Białówna reacted in her usual way, not in the manner of the concentration camp, but gently and humanely. She comforted the heartbroken mother in fluent Russian, giving her hope and promising to help. She kept her promise. The baby was named after her, survived, and is now a qualified children’s doctor in the USSR.

Although Dr Białówna’s life was full of ordeal, she lived to a ripe old age, though seriously ill for a long time. The strain of all the efforts she had made and all the traumatic experiences sustained in prisons and concentration camps left a permanent mark on her health. Like most survivors, she had to put up with the post-concentration camp syndrome, and despite intensive treatment suffered from several illnesses and disorders, including myocardial degeneration. In the last period of her life she had trouble with swallowing solid food and respiratory problems due to bronchial changes. For a certain period of time she had to ask for help, even with things like writing letters. She died in Białystok on 7 February 1982 and was buried on 10 February in the family grave in the parish churchyard. Mourners who attended her funeral remember its poignant atmosphere and the deeply moving funeral orations delivered at her graveside.

Krętowski and Taraszkiewicz give a list of the medals and distinctions conferred on Dr Białówna, also confirmed in the records. In 1938 she was awarded the Bronze Medal for Long Service.45 After the War the following honours, medals, and distinctions were conferred on her: the Silver Medal with Swords for Valour (1946),46 the Gold Cross of Merit47 (1950), the Knight’s Cross48 (1958), the Officers’ Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta49 (1959), the Medal for the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic50 and the Millennium Badge51 (1979), the Badge of Merit for the Voivodeship of Białystok,52 the Badge of Honour for Distinguished Service in the Białystok Health Service,53 the Polish Red Cross Badge of Honour (First, Second, and Third Class),54 the Gold Badge for Members of the Society of Children’s Friends,55 the Gold Badge for Members of the Polish Association of Invalids,56 the Gold Badge for Members of the Polish Association of the Deaf,57 and the Badge of Honour of the Society for Informed Maternity.58

Dr Irena Białówna entered the annals of history, not only for the years when Poland was occupied by Nazi Germany, but also for the history of medicine and paediatrics in Poland.

***

Translated from original article: S. Kłodziński, Dr Irena Białówna. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1983.

- In People’s Poland and other countries under the Communist regime it was standard practice to record the names of all places which later found themselves on Soviet territory as belonging to the USSR, even for periods in history well before the Soviet Union emerged as an internationally recognized state (1922).

- Szkoła Główna Warszawska (1862-1869)—an institution of higher education in the Russian zone of Partitioned Poland. Closed down in reprisals following the anti-Russian 1963 Uprising.

- Simbirsk, now known as Ulyanovsk, a city on the River Volga, 705 km south-east of Moscow.

- In the late 18th century Poland was partitioned by three neighbouring states, Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and lost its independence for 123 years (1795-1918). During this period Poles staged a number of uprisings against the Partitioning Powers, the one in 1863-64 being a major anti-Russian insurrection.

- A city in north-eastern Poland.

- A job status similar to internship.

- Przysposobienie Wojskowe Kobiet.

- Ubezpieczalnia Społeczna, now known as Powszechny Zakład Ubezpieczeń Spółka Akcyjna (PZU).

- Rejon pediatryczny II Polikliniki Miejskiej w Białymstoku.

- Związek Walki Zbrojnej — Armia Krajowa (Union of Armed Struggle – Home Army)—the names of successive Polish resistance organisations.

- Wojskowa Służba Kobiet.

- Szaniec—a splinter group of the Polish underground resistance movement.

- Sipo—die Sicherheitspolizei (the Nazi German security police).

- Sicherheitsdienst—the Nazi German security service.

- “Z historii rewiru w Brzezince.” Polish version in the 1979 volume of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, pp. 164–175, online at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/polish/171129,volume-1979.

- Published in Polish as Kalendarz wydarzeń w KL Auschwitz, Oświęcim: Wydawnictwo Państwowego Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1992 (First published 1960). First American edition: Auschwitz Chronicle, 1939-1945, New York: H. Holt, 1990.

- See above, comment 16.

- At the time Vitebsk was in the USSR under German occupation, now in Belarus.

- In 1942-43 the Germans carried out Aktion Zamość, deporting the Polish population of the Zamość region with the aim of resettling it with Germans. Over 30 thousand children were abducted, the ones deemed “good for Germanisation” were sent to German families for adoption, and the rest were sent to prisons and labour or concentration camps, where most of them died or were killed.

- The Warsaw Uprising of 1944, not to be confused with the Ghetto Uprising of April 1943. In August 1944 during the Uprising the Germans started to evict the civilian population of Warsaw, deporting about 13 thousand to Auschwitz. See https://dzieje.pl/aktualnosci/rocznica-deportacji-przez-niemcow-warszawiakow-do-auschwitz.

- As may be noticed, the article is inconsistent when it comes to Hanna Wróblewska age, and she is said to have been 6 years old in other fragments. So far it has proven impossible to determine Wróblewska’s date of birth to solve this discrepancy.

- Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz, war criminal. Put on trial after the War, sentenced to death, and hanged on the same gallows that had been used to execute inmates.

- A dessert consisting of fruit, water, and gelatine thickened with cornflour or potato starch.

- See the article on her on this website.

- Dr Baraniecka-Szaynokowa worked as a courier in the Polish resistance movement.

- Dr Olga Nikitichna-Klimenko. See Maria Ciesielska, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-1945), Warszawa: WUM, 2015, p. 74; online at http://polska1926.pl/files/2691/files/szpital-obozowy-dla-kobiet-w-kl-auschwitz-birkenau-1942-1945.pdf.

- In German concentration camps convicted criminals wore a green triangular badge on their prison gear.

- Prisoner-doctors in Auschwitz hid the patients most at risk of being selected for death, to keep them from being noticed by the SS doctors making selections.

- For a comment on the inconsistency in Wróblewska’s age as given by the article, see note 21.

- Name-days are a similar tradition to birthdays, celebrated in Catholic countries on your patron saint’s feast day.

- Dr Alicja Piotrowska-Przeworska. See Maria Ciesielska, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-1945), Warszawa: WUM, 2015, pp. 99-101 online at http://polska1926.pl/files/2691/files/szpital-obozowy-dla-kobiet-w-kl-auschwitz-birkenau-1942-1945.pdf.

- At the time the city, then still in German hands and known as Breslau, was being attacked and bombed by Soviet troops from the air, and besieged from February until 6 May 1945, when it surrendered to the Soviets after what was one of the last, heavy battles of World War Two.

- Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg, a concentration camp about 30 km north-west of Berlin.

- A concentration camp 30 km north of Berlin

- Wojewódzki Szpital im. Jędrzeja Śniadeckiego w Białymstoku.

- Klinika Pediatryczna Akademii Medycznej w Białymstoku.

- Państwowa Szkoła Położnych, Państwowa Szkoła Pielęgniarstwa, and Szkoła Felczerska.

- Wydział Zdrowia Urzędu Wojewódzkiego w Białymstoku.

- Specjalistyczny Zespół Opieki Zdrowotnej nad Matką, Dzieckiem i Młodzieżą w Białymstoku.

- Klinika Zakaźna Chorób Dzieci Akademii Medycznej w Białymstoku.

- The Polish Parliament.

- Founded in 1957 as Towarzystwo Świadomego Macierzyństwa, now known as Towarzystwo Rozwoju Rodziny (the Society for the Advancement of the Family).

- Instytut Matki i Dziecka.

- In Poland the professor’s title is generally awarded on the basis of a candidate’s scientific achievement, especially the number of his or her publications.

- Brązowy Medal za Długoletnią Służbę.

- Srebrny Krzyż Walecznych z Mieczami.

- Złoty Krzyż Zasługi.

- Krzyż Kawalerski.

- Oficerski Krzyż Orderu Odrodzenia Polski.

- Medal 30-lecia Polski Ludowej.

- Odznaka Tysiąclecia.

- Odznaka Zasłużony Białostocczyźnie.

- Odznaka Za Wzorową Pracę w Służbie Zdrowia.

- Honorowa Odznaka I, II i II stopnia PCK.

- Złota Odznaka Członkowska Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Dzieci.

- Złota Odznaka Członkowska Polskiego Związku Inwalidów.

- Złota Odznaka Członkowska Polskiego Związku Głuchoniemych.

- Odznaka Honorowa Towarzystwa Świadomego Macierzyństwa.

- Front Jedności Narodowej (FJN) was a political organisation affiliated to the PZPR (the ruling Communist Party) in the Polish People’s Republic.

- The editors of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim compiled several questionnaires which they asked survivors to complete, and used the information they received in their research.

- English version: The Auschwitz Chronicle (first edition 1990).

Notes 1–20, 21–28, and 30–61 by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project. Notes 21 and 29 courtesy of Maria Ciesielska, Expert Consultant on the History of Medicine for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

This biographical article was written on the basis of the following sources:

Personal records

1. Curricula vitae and biographies

- Irena Białówna’s biography (typescript of four and a half pages with dense line spacing, undated; Dr Białówna sent me this text before she died);

- An outline of Irena Białówna’s CV (one-page typescript with dense line spacing, undated);

- A survivor’s questionnaire filled in by Irena Białówna for the Auschwitz State Museum (No. IV-8521/2698/3077/73; transcript dated 18 May 1982).

2. Copies of certificates

- Certificate No. 771 issued by the Voivode of Białystok on 30 Jun. 1938, for the award of the Bronze Medal for Long Service to Irena Białówna;

- Certificate issued by the Central Board of the Polish Red Cross on 10-13 May 1974, for the award of honorary membership of the Polish Red Cross to Irena Białówna;

- Certificate issued to Irena Białówna by the Department of Health and Social Welfare at the Białystok Voivodeship Office on 8 Mar. 1977 “for distinguished merit in the enhancement of public health and for social service”;

- Certificate issued to Irena Białówna by the Białystok Branch of the Polish Paediatric Association to mark the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic and of the Polish Paediatric Association (undated);

- Transcript of the award holder’s identity card issued to Irena Białówna recording the conferral of the Memorial Medal for the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Polish People’s Republic (dated 22 Jul. 1974).

3. Official documents

- Letter to Irena Białówna from the Białystok Educational Authority (No. BP-13095/45, 9 Nov. 1945);

- Letter from Prof. M. Michałowicz to the Department for Education and Training at the Ministry of Health (transcript of a densely spaced typescript of one page, dated 7 Apr. 1953);

- Contract concluded on 26 Sept. 1955 between the Rector of the Białystok Medical Academy and Irena Białówna;

- Transcript of the letter of confirmation of 25 Jan. 1957 issued by the National Electoral Committee;

- Transcript of Minister J. Sztachelski’s letter of 1 Jul. 1959 to Irena Białówna thanking her for organising the visit of representatives of the World Health Organisation to the Białystok Voivodeship;

- Letter No. MN-136-A/61 of 21 Apr. 1961 from the Minister of Health and Social Welfare to Irena Białówna;

- Letter No. RN-40/62 of 12 Feb. 1962 from the Scientific Council attached to the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare to Irena Białówna;

- Letter No. M.O. 7078/62 of 4 Oct. 1962 from the Institute for the Mother and Child to Irena Białówna;

- Transcript of the letter of 17 Jul. 1979 from the Voivodeship Physician Dr Marian Panek to Irena Białówna, notifying her of the entry of her name in the register of persons with distinguished service for the Białystok medical service;

- Transcript of the letter from the Chairman of the Białystok Voivodeship Committee of the Front of National Unity59 to Irena Białówna, notifying her that her name had been entered in the book of honour of persons with distinguished service for the Voivodeship of Białystok, 1944-1977 (undated);

4. Miscellaneous

- Centre International de 1’Enfance. Cours sur les problèmes de protection maternelle et infantile. 5 novembre—16 décembre 1956. Liste des auditeurs (attendance list of four A4 pages for a French paediatrics course);

- Certificate of attendance for this course.

Letters

1. Family letters

- From Irena Białówna to Stanisław Kłodziński, 14 Aug. 1974, 26 Mar. 1975, 23 Apr. 1978 (with drawing of the layout of part of the women’s camp and hospital in Birkenau attached), 8 Aug. 1978, 18 Sept. 1978, 30 Sept. 1978, 6 Nov. 1978, 13 Nov. 1978, and a 1978 letter with no day or month date;

- From Irena Białówna’s sister, Janina Krzyżanowska of Białystok, to Stanisław Kłodziński, 15 Jan., 1 Mar., 11 Apr., 6 May, and 7 May 1982; and to H. Włodarska, 6 Jul. 1975, and 12 Feb. and 12 Mar. 1982 (with information and documents concerning her deceased sister);

2. Letters from members of the medical community

- From Jan Krętowski and Franciszek Taraszkiewicz to the editors of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 9 Feb. 1981;

- From Jan Krętowski to Stanisław Kłodziński, 7 Jun. 1982, with a copy of the funeral oration delivered by Dr Franciszek Taraszkiewicz at the graveside of Irena Białówna, 10 Feb. 1982 (10-page typescript);

- Postcard from J. Kuźmiński to Jan Masłowski, 14 Mar. 1982.

3. Letters from the Auschwitz Museum and its associates

- From Danuta Czech to Stanisław Kłodziński, with remarks on Irena Białówna’s typescript account of the Birkenau prisoners’ hospital, 3 Jul. 1978;

- Letter No. IV-8520-81/1346/82 of 18 May 1982 from the Museum to Stanisław Kłodziński, with basic information on prisoner Irena Białówna (on the basis of a collection of concentration camp letters, No. D-AuI-1/4404, Ref. No. 159608; numbered lists of prisoners on transports arriving in Auschwitz-Birkenau; and replies to the team’s questionnaires).60

Publications and unpublished materials

- Irena Białówna, “Dr Ernestyna Michalikowa,” (unpublished typescript of three-and-a-half pages, no date, in the collections of Stanisław Kłodziński;

- Irena Białówna, “Uwagi do relacji kol. Zofii Zybert,” (comments to Zofia Zybert’s relation, unpublished typescript of two pages;

- Irena Białówna, “Z historii rewiru w Brzezince,” (Episodes from the history of the Birkenau prisoners’ hospital) Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1979: 164–175 (Polish text on this website, https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/polish/171129,volume-1979) . Reprinted in Okupacja i medycyna, Vol. V, Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza, 1984;

- Danuta Czech, “ Kalendarz wydarzeń obozowych,”61 Zeszyty Oświęcimskie Oświęcim: Państwowe Muzeum w Oświęcimiu, 1960: 95–96;

- Janina Komenda, “Wspomnienia z obozu Auschwitz II — Birkenau.” (150-page typescript of recollections of Birkenau; an excerpt entitled “W rewirze Brzezinki” (on the prisoners’ hospital), was published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1982: 194–205 (Polish text available on this website, https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/polish/171129,volume-1982);

- Zygmunt Kosztyła, Wrzesień 1939 roku na Białostocczyźnie. Białystok: Białostockie Towarzystwo Naukowe; Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1968;

- Janina Kościuszkowa, “Losy dzieci w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1961: 60–61; English translation, “The fate of children in Auschwitz,” available on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/205964,the-fate-of-children-in-auschwitz

- Jan Krętowski and Franciszek Taraszkiewicz: “Wspomnienia wydarzeń wrześniowych, pracy konspiracyjnej, pobytu w obozach koncentracyjnych oraz działalność lekarska dr med. Ireny Białówny po wyzwoleniu w Polsce Ludowej” (Dr Białówna’s memoirs of the Second World War and her post-war work in the medical profession; 11-page typescript, 1981, with biographical details and passages from Dr Białówna’s recollections);

- Stanisława Leszczyńska, “Raport położnej z Oświęcimia.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1965: 104–106, English version: “A midwife’s report from Auschwitz,” on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/193055,a-midwifes-report-from-auschwitz ;

- Dr Irena Białówna’s obituaries in the Białystok local press;

- Obozy hitlerowskie na ziemiach polskich 1939—1945. Informator encyklopedyczny. Warszawa: PWN, 1979, p. 100—103: Białystok;

- Helena Grunt-Włodarska: “Ze szpitala kobiecego obozu w Brzezince,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1970: 241. English version: “Recollecting the women’s hospital at Birkenau,” available on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/221068,recollecting-the-womens-hospital-at-birkenau;

- Wacława Zastocka, “Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim 1979: 189–195. English version: “Dr Wanda Baraniecka-Szaynokowa,” on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/247223,baraniecka-szaynokowa ;

My personal recollections of Dr Irena Białówna.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.