Author

Leon Stasiak (Leiser Sylman), 1915–2000, survivor of Buchenwald and Auschwitz-Birkenau (prisoner no. 68677), one of the leaders of the resistance movement in Buna-Monowitz (a subcamp of Auschwitz-Birkenau).

Original Editors’ note: In tribute to the late Robert Waitz, a concentration camp survivor who was one of our authors, we are publishing this memorial article by Leon Stasiak. Our readers have had to opportunity to read two of Professor Waitz’s articles on Nazi German concentration camps. The first, “Zmiany chorobowe u byłych więźniarek obozów koncentracyjnych,”1 published on pp. 41–50 of the 1963 edition of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, is the Polish translation of his probing study entitled “La pathologie des deportées,” which was published in La Semaine des Hôpitaux, 1961, 37, 33, pp. 1977–1983. His second article published in our journal was co-authored with Dr Marian Ciepielowski and is entitled “Doświadczalny dur wysypkowy w obozie koncentracyjnym.”2 It appeared in the 1965 edition of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (pp. 68–69). This recollection of the concentration camp episode in Professor Waitz’s life does not review his scientific achievements or his publications.

Professor Robert Waitz at the Institute of Haematology in Strasbourg. Source: A.S.I.J.A., photo by D.R., via http://www.ajpn.org. Click the image to enlarge.

Professor Robert Waitz, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor No. 157261, was born in 1900 and died on 21 January 1978 in Strasbourg, the city in which he lived and worked for many years. Professor Waitz was a physician and medical scientist, an activist of the international veterans’ movement, a man of integrity with a friendly and sympathetic attitude, and dedicated to his patients. Professor Waitz deserves a full and exact biography, but here I shall try to pay a tribute to him with just a few recollections.

The Gestapo arrested him in July 1943, and in October of the same year he was sent to Auschwitz and confined in Auschwitz III (i.e. Buna-Monowitz). Many survivors have commemorated Professor Waitz in their recollections of the concentration camp. They write that he did all he could to help sick inmates and save lives. [Editors’ note: Several articles have already appeared in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim on the prisoners’ hospital at Monowitz. Authors include Dr Antoni Makowski3 and Dr Zenon Drohocki,4 and their articles are listed in the contents and bibliographies at the back of previous volumes of this journal.]

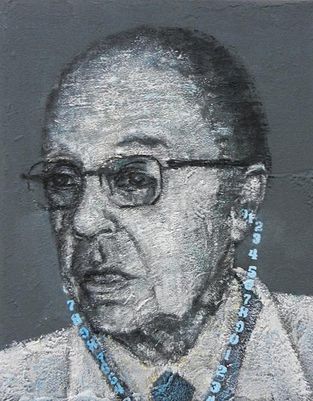

Professor Waitz took a very serious and conscientious approach to his work in the camp hospital. He used to say that it let him forget he was a prisoner in the worst of all the concentration camps. He examined his patients closely and took a long time over it, asking a lot of questions and seeking the advice of other physicians. He took his time. For him a sick inmate was not just a number,5 but a patient who needed his assistance, assistance which he provided in the same way he had done when he was a free man, as if he could then proceed to the routine medical procedure, administering the right medicines and the regular treatment.

Sometimes I had the impression that Waitz refused to reconcile himself to the fact that his practice of the art of medicine had been confined, imprisoned along with him. At first I thought that had not yet learned the principles that obtained in the camp or come to terms with the fact that by its very nature a concentration camp ruled out the potential for proper medical treatment, and that with time he would understand that in the hell of Auschwitz he was just as helpless as everyone else. But he was just as conscientious and resolute even during the evacuation march in January 1945, when he continued to provide medical assistance to sick prisoners. Waitz was absolutely right to believe that having an unhurried talk with the patient and giving him a thorough examination raised his determination to survive, which was important in any situation, and especially in a concentration camp.

Often I used to wonder whether Professor Waitz was examining patients so meticulously and asking them such a lot of questions for another reason as well—for scientific purposes, collecting his concentration camp medical observations and experience, for use after the War (if and when we won it). And, sadly, the concentration camp supplied him with a lot of research material. The camp offered disease the most favourable conditions to launch a frontal attack on the human body and develop to its full extent. And indeed, right up to the final weeks of his life Professor Waitz continued to return to the observations, reflections, and statistical data he had collected on inmates’ morbidity and the devastating aftereffects of incarceration in a concentration camp on the life and health of those who survived. These were the subjects of his publications.

Professor Waitz treated his work in the prisoners’ hospital as a fight against the German occupying power for the lives and health of prisoners. What the concentration camp was ruining had to be restored by any means available. By fighting for prisoners’ health and helping those in need, not only was he doing his duty for the sick, but also with respect to himself; he was meeting the moral obligations he had undertaken to fulfil when he decided to dedicate his knowledge and skills to medicine.

Along with Professor Waitz there was a group of people confined in the Krankenbau6 of Auschwitz III, working hard and doing all they could to save prisoners and stop the pageant of death. A job in the prisoners’ hospital gave them a better chance of survival, but Professor Waitz was not working to survive himself, but to help others survive. Regardless of the risks, he made a courageous contribution to the effort to save patients’ lives by keeping them in hospital for longer than the rules permitted and hiding those who were still unfit for work after being discharged. I remember him bravely helping to save a Soviet pilot who was a prisoner in our camp from being punitively transferred to Flossenbürg.7 This pilot developed a high temperature after an injection, which made him transportunfähig (unfit for transportation) and saved his life.

All the efforts to provide illicit help to prisoners could only be done if the doctors and medical ancillaries providing it worked together in an atmosphere of solidarity and comradeship, keeping it all absolutely secret. The SS responded to all such operations (if discovered) in exactly the same way: death was the penalty for those who defied the concentration camp prohibitions and system to save the lives of other prisoners.

Waitz was particularly distressed when he saw young prisoners, teenagers—still boys in fact—who were sick due to hunger and hard labour, injured or severely battered. Many of those whom Herr Doktor Waitz helped or encouraged and strengthened their will to survive came to see him in the evening after work for a short talk. Knowing that there was someone supportive and sympathetic to them who they could talk to was an invaluable asset, especially for lonely young people who had been deprived of their families and lived with the knowledge or suspicion that the Germans had murdered their nearest and dearest in the camp. Waitz was also in touch with his friends and acquaintances. On Sundays, whenever he had the chance, he would visit the blocks where people who had arrived in the same transport as himself were accommodated. He would have a handful of tablets with him, although he used to say that some bread would have been more useful.

In 1944 Allied air raids bombed the I.G. Farben Buna plant in which Auschwitz III prisoners worked. Our camp was not far away, so the Allied aircraft flew overhead and dropped their bombs quite near us. During one of the air raid alarms I spotted Waitz at the end of one of the barracks. He was kneeling with his hands pressed down on the floor. I couldn’t make head or tail of it, since Waitz wasn’t afraid of air raids, just like the rest of us. Whenever there was an Allied air raid in broad daylight, we all knew it heralded the end of Nazi Germany. We wanted the bombs to do as much damage as possible to Germany, even if it meant that some of us would be victims. So I went up to Waitz and asked if he was all right. He went red in the face and got up. It turned out that he had taken the microscope, an invaluable asset for the hospital, and crouched down over it to protect it with his body and save it from being damaged or destroyed in the air raid. I saw that he was a bit embarrassed because he didn’t want anyone to notice that he was trying to protect the microscope in this way.

Francince Mayran, portrait of Prof. Robert Waitz. Source: A.S.I.J.A., photo by D.R., via http://www.ajpn.org Click the image to enlarge.

After liberation Professor Robert Waitz organised and directed the Strasbourg Blood Transfusion Centre and Institute of Haematology,8 and was a friend and close working partner of the Warsaw Institute of Haematology.9 He shared his knowledge and expertise with us, visited us to deliver lectures, granted scholarships to our staff and gave them the opportunity to train in the Centre of which he was head.

The French government and the chief scientific authorities of France conferred their top distinctions and medals10 on Professor Waitz for merit in scholarship and research, the public medical service, his active contribution to the French resistance movement, and his exemplary courage in the Nazi German concentration camps (Auschwitz and Buchenwald).

For several years Professor Waitz served as Chairman of the International Auschwitz Committee. For survivors he was an authority. With a reputation for circumspection and patience, he never cut a discussion short or tried to impose his own opinions or approach to the resolution of controversial issues.

We have lost a man who was a moral authority, renowned for his knowledge and expertise, a person who enjoyed the respect of all who knew him.

Notes- The English translation of the Polish version of Waitz’s article, “Investigation of the aftereffects of female survivors’ imprisonment.” Click the link to read it.

- The English translation of an article discussing the work of Prof. Waitz and Dr Ciepielowski for the production of anti-typhus vaccine, and entitled “Sabotage at the Buchenwald SS Hygiene Institute. Dr Marian Ciepielowski,”. Click the link to read it.

- The English translation of Antoni Makowski’s article is available on this website as “Prisoners’ improvements to the hospital facilities in the Monowitz camp” (original title “Niektóre osiagnięcia organizacyjne szpitala w Monowicach”). Click the link to read it.

- The English translation of Zenon Drohocki’s article is available on this website as “Electric shock at Monowitz hospital” (original title “Wstrząsy elektryczne w rewirze monowickim”). Click the link to read it.

- In German concentration camps the SS and functionaries identified prisoners not by their names but by their prison number, which was tattooed on their body. In other words, a prisoner’s identity was reduced to his or her prison number.

- German term for “hospital building.”

- Flossenbürg was a German concentration camp in Bavaria. Its prisoners worked in a granite quarry, and mortality in the camp was very high due to the hard labour and bad conditions.

- After the War Professor Robert Waitz was appointed to the Chair of Haematology of the University of Strasbourg. Cf. http://judaisme.sdv.fr/perso/doctor/waitz/waitz.htm.

- Instytut Hematologii w Warszawie.

- Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur, Commandeur de l'ordre des Palmes académiques, Commandeur de l'ordre de la Santé publique, titulaire de la médaille de la Résistance avec rosette, Croix de Guerre avec palme et étoile d'or. Cf. http://judaisme.sdv.fr.

Notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, the translator of the above article and Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.