Author

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English.

Editors’ Note: The article was originally published in 1961. The author of did not include sources for his calculations, and hence the numerical data in the text cannot be verified. The number of 4 million victims murdered in the gas chambers, given in the text, is clearly not corroborated by the current state of research, and the calculations lack supporting data. Many former prisoners attempted to provide similar estimates in their memoirs, sometimes based on sources, and sometimes only on the basis of other publications. This is the reason behind the continued discussion over the total number of the victims and repeated attempts to estimate the daily mortality rate, which, given only ca. 5% of the camp documentation is extant, seems hardly feasible.

Since late 1990s, historians base their estimates on the research results of Franciszek Piper (a retired director of the Research Department of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum), who investigated and listed a number of available sources.

When Germany invaded and defeated Poland in September 1939, Hitler had already decided that the Polish people were to be exterminated. The number of Polish soldiers killed in the defence campaign was just a fraction of the total death toll Poland sustained under Nazi German occupation. Overall, about 6 million lives are estimated to have been lost and as much as 40% of the country’s material assets destroyed. However, these figures can give but a rough idea of the scale of destruction, and the implications of the term “Nazi German occupation” can be fully comprehended only by those who survived its terrors.

The German soldiers who obeyed the commands of Hitler and Himmler and used highly sophisticated, precise, reliable, scientifically proven methods of killing, targeted the Polish nation, which stood alone and exhausted, and stripped of all human rights. Yet, though the population was being decimated, at the same time it was growing more and more determined to defy the enemy and mount up resistance. The fact that the Nazi jails were overfull and whole towns and villages were annihilated had no deterrent effect upon the Poles, who were made desperate by the atrocities. As the weeks, months, and years of occupation were passing by, the resistance movement was becoming stronger and stronger. The quickly dwindling ranks of the underground combat units had to be replenished with new, brave recruits, both male and female, representing all walks of life; some of whom were as young as seven or eight years of age. The Polish response to the policy of total extermination was total resistance. The whole country was a front line, and fighting went on in every city and hamlet, every household and forest, north and south, on the seacoast and in the mountains. The ghettos and concentration camps, those offices which still employed Poles, the factories and farms all became theatres of war.

Therefore it is impossible to assess the damage that resulted from such fighting. It was only in 1945, when the Third Reich was defeated, that the world could revisit those parts of Europe that had been German-occupied, now full of smoking ruins and reeking of blood, as if they had been ravaged by the hordes of Genghis Khan.

In the years following the war, it was difficult even to check out who and what had gone missing.

When an appeal was issued to members of the medical profession to step forward and start working for a now liberated Poland, it turned out that about 5 thousand Polish physicians, 2.5 thousand dentists, and 3 thousand other medical staff had been killed (after statistical data collected by Cyryl Kolago and published in 1946 by the medical weekly Polski Tygodnik Lekarski, p. 916). Of all the graves of Polish doctors and other people who saved lives during the war and now lie buried in countless places where fascism strove to eradicate humanism, the largest final resting place for human ashes is the marshy expanse of Auschwitz.

The figures for the registered prisoners1 are beyond comprehension. Prisoners were registered in several, differently marked categories and series, and the data is as follows:

| Number of men | Number of women | |

|---|---|---|

| Prisoners in the main registration system | 202,499 | 90,000 |

| Jewish prisoners, series A | 20,000 | 30,000 |

| Jewish prisoners, series B | 15,000 | – |

| Erziehungshäftlinge (prisoners to be “re-educated”), EH | 10,000 | 2,000 |

| Soviet prisoners of war, R | 11,780 | – |

| Roma and Sinti prisoners, Z | 10,094 | 10,849 |

| Total | 269,373 | 132,849 |

Also, there were about 3 thousand “police prisoners” (Polizei-Häftlinge, PH).

This means that from 14 June 1940 to 18 January 1945, the day when the camp was evacuated, 405,222 persons were registered as Auschwitz prisoners. It is estimated that out of this group, about 65 thousand survived and 340 thousand were killed, so the proportion of survivors is about 13.5%. It must be noted that as many as 4 million victims,2 mainly Jews from different countries, were not registered, but herded straight into the gas chambers of Birkenau.

The Tesch & Stabenow3 company, a producer of chemical gas with a plant near Dessau, confirmed it had dispatched 19 thousand kg of Zyklon B to Auschwitz (as stated by Rudolf Höss in his memoirs, p. 341).4

Out of the registered prisoners of Auschwitz, 267,985 died in the camp, while the remaining 82,157 fatalities lost their lives in the transports or in other death camps to which they were transferred. The camp was in operation for 1,778 days and its victims perished by starvation, torture, hard labour, infectious diseases, or by being shot or gassed. On average, on each of those nightmarish days, the Grim Reaper claimed the lives of 190 registered prisoners.

French statistics show that for every 100 French prisoners incarcerated in Nazi German death camps, only 10 survived, and by 1954 only half of them were still alive and most of them were disabled.

The daily death rates per one thousand prisoners that can be calculated on the basis of the preserved 1942 registers were 511 at the lowest and 10,402 at the highest. This figure for the Soviet POWs reached 73,000.5 As the number of prisoners ranged from 12 thousand to 18 thousand depending on the day, these figures show that every year Auschwitz killed several large contingents of new arrivals (the figures are quoted after Professor Olbrycht6).

The extant materials of the resistance movement in the camp include a report dated 25 April 1943, which says,

In Birkenau, they are hastily digging up the mass graves of 11 thousand Soviet POWs who were killed while “at work” during the two winter months of 1942; the bodies are being burnt to remove the evidence.

Given all these figures, what was the Häftlingskrankenbau, the HKB, that is the prisoners’ hospital in Auschwitz, which inmates called the rewir?7 What role could it possibly have played? These questions should be given serious consideration, especially as Auschwitz meant the omnipresence of death, and everything that went on there was intended to destroy human life. As DrWładysław Fejkiel8 rightly observed in his paper delivered on 3 February 1960 at a meeting of the Polish Medical Association,9 the prisoners’ hospital was established by the SS as a smokescreen: its propaganda purpose was to hide the real motives behind the camp’s operations. Upon hearing that Auschwitz had a hospital for its prisoners, people were supposed to reject the facts about the ruthless extermination that went on in the camp. The SS relied on that logic all too often, showing the hospital during all the inspections, both official and unofficial ones. Dr Fejkiel realized that the Auschwitz hospital was actually intended as an instrument of, and a means to the mass killings. The camp, which was supposed to provide a cheap labour force, could be regularly relieved of the burden of sick prisoners, who—if they stayed alive for too long by the SS standards—were given lethal phenol injections or selected for death in the gas chambers. Aktion 14f13,10 which was initiated on Himmler’s secret order, was to eliminate all the sick and disabled prisoners of Nazi German camps. The code-name 14f13 appeared on all the documents of the SS-Totenkopfverbände11 supervised by Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. The campaign was developed on a large scale also in Auschwitz. From 1 September 1941, the SS doctors started killing sick prisoners with intravenous injections of petrol or phenol to reduce the number of patients in the hospital. Later the method was modified, and injections of a 30% solution of phenol were administered straight into the heart. On very wet or cold days, when hundreds of sick prisoners turned up to be admitted, the number of those due for “death by phenol” rose to 60, 80 or more. The task of giving people lethal injections was delegated by an SS physician to the SS Sanitätsdienstgrad,”12 who in turn made use of prisoners working in the Leichenhalle (mortuary) of Block 28 and later in Block 20 to assist in the mass killings. The average daily number of such executions was 30–40, and the whole procedure took about 60–90 minutes. The hospital records routinely registered them as death of natural causes, reiterating the same formulaic, fabricated diagnoses.13

The reports compiled by the Auschwitz resistance movement which I have quoted discuss the procedure of what was called “jabbing” on many occasions. For instance, “jabbing is still going on, though on a smaller scale, and involving only the severe cases. If you have acute TB, nothing can help you, not even if you are a Reichsdeutsche.”14 Another scrap of information from April 1943 concerns the Roma camp, which had its own hospital:

The discipline is not so strict there. But those who are seriously sick with TB or exhausted are given a jab in the heart, as we hear from the staff there. I think this should be made widely known.

Phenol injections were applied from September 1941 to mid-1944 and at least 25,000 registered prisoners of Auschwitz I were killed in this way, having been diagnosed by a Lagerarzt15 as “unfit for work” or sentenced to death by the camp’s Politische Abteilung.16 The Polish doctors estimated that lethal injections were given to about 35,000 prisoners of Auschwitz I. They were administered by Josef Klehr,17 Herbert Scherpe,18 and Emil Hantl,19 all of whom were SDG orderlies. Sick prisoners also had to attend “choosies” (as inmates called these events), i.e. selections for death by gassing, which the Lagerarzt conducted on his hospital rounds. Usually once a month, in the presence of the SS orderlies and the prisoner staff, he would “examine” all the bedridden patients. He examined patients only by looking at them and their temperature charts, but never actually touching them. The Lagerarzt collected up the temperature charts of the patients he had selected, with their prison numbers on their chart. A decision was taken on the basis of the list of those numbers how many trucks would be needed in front of the hospital. The selected men were put on them and dispatched straight to the gas chambers in Birkenau. Every time there was a choosie, there were hundreds of patients less on the hospital records.

Lastly, the prisoners’ hospital was intended to serve as a cheap lab for Nazi German pseudo-medical experiments: a guinea-pig or a hamster would have been more expensive than a camp detainee and would definitely not have rendered such reliable results. Experiments that were to test the effectiveness of pharmaceuticals manufactured by German companies cost hundreds of lives. Sterilization, castration, artificial fertilisation, chemical burns, anthropological measurements, experiments on twins, especially identical ones, building up collections of skeletons, infecting people with typhus, cancer studies, and unnecessary operations on healthy people were just some of the charges that were brought up in the Doctors’ Trial before the Nuremberg Military Tribunal in 1946–47. In a report dated April 1943, the camp resistance movement wrote that Block 10 of Auschwitz I became a lab for Nazi human experimentation where prisoners were castrated, sterilised or underwent artificial insemination. These procedures were authorised by the Waffen SS Hygiene Institute based in Berlin.20 Another message, dispatched in mid-May 1943, includes more details concerning Block 10:

It is being used as an experimental lab reporting to Waffen SS Süd-Ost. It has a few rooms accommodating about 200 Jewish women and 15 Jewish men. The experiments involve artificial fertilisation, castration, and sterilisation. Everything’s top secret: the window shutters are kept closed. So far, several women have been sterilised and all 15 men have been castrated, after their sperm was taken. It’s all about test tube babies. Almost all the Jewish women come from Greece, but that may change. They haven’t been registered. For the purpose of roll calls, it seems they are counted as dead.21 I suppose the outcome of these experiments will just be dead bodies, nothing more.

The prisoners’ hospital in Auschwitz had one more important role to play: it was to isolate those with infectious diseases and prevent epidemics from spreading in populations as vast as those in the concentration camps. Epidemics could ruin Himmler’s plans to use the free labour force, weaken the military potential of the Third Reich, or worse still, affect the SS men and their families, inflicting irreparable damage. The most brutal methods were used to stop epidemics. For instance, typhus patients were gassed. The archives of the camp resistance movement include an illicit letter which describes a selection among prisoners stricken with typhus, which took place on 29 August 1942:

29 August was a day when 740 typhus patients were poisoned. I was sick too, and it was by pure chance that I avoided their fate. That was my most tragic day, it cost me a lot to see all those atrocities, I had to watch my colleagues and friends walking away to be killed. I saw the dejected, helpless doctors. I talked to one of them. He had tears in his eyes and was unable to calm down. So much work, so many sleepless nights, so many people who had evaded the gaping jaws of the disease—about 500 had already passed the crisis and survived—and all in vain! I felt for him then, I could not hold back my tears any more, and cried like a baby.

The delousing procedure did not seem to be effective enough, as the clothes that went into the fumigation room were returned with live lice and nits on them. There were no other typhus prevention measures such as vaccines.

It is also correct to assume that besides all these reasons, there was another rationale behind the existence of a prisoners’ hospital in Auschwitz: “the elect” of German society wanted to use their privileges and implement their “praiseworthy mission of genocide” far from the front line, so as not to risk their own precious lives.

Perhaps one more reason why the hospital was established was that Auschwitz was uncritically modelled on and built with typical German precision according to the designs of concentration camps that had been in existence in the Third Reich since 1933. Therefore no new design had been offered for Auschwitz more in keeping with the functions of a death camp. Treblinka and Belzec22 had no hospitals.

When we analyse the first stage in the operations of the Auschwitz hospital, which lasted until 1942, we have to admit that the establishment fulfilled all the functions that had been imposed on it by the SS. It provided no treatment whatsoever and the name was just a façade. The hospital was the antechamber to the Leichenhalle (mortuary). At this time, Auschwitz was a place for the ruthless extermination of Poles. A report compiled by the camp resistance movement and dated 24 November 1942 says:

The Krankenbau has about 2,200 inpatients. It consists of three blocks. No. 28 is the internal ward with about 300 patients, the dispensary, storage rooms, and the lab. No. 21 holds the surgical ward and the dental surgery, the operating theatre, and the Schreibstube (clerk’s office); the number of patients is about 600. No. 20 has about 200 patients with Durchfall [starvation diarrhoea], 40 patients officially diagnosed with Fleckfieber [typhus] and 156 illicitly admitted “for observation,” about 30 patients with paratyphus, about 10 with typhoid, 90 with erysipelas, 15 with meningitis, 2 with diphtheria, 150 outpatient convalescents, and 130 medical staff, including about 30 doctors; all of them are prisoners, some are Jewish. These data do not include the Raisko sub-camp. The officially provided medications cover 20% of the demand, the medicines from you amount to 70%,23 and those that are stolen from the SS storerooms make up about 10% of the needs. Daily, about 30 patients die of natural causes, while a year ago it was 80 patients daily. Every day, from 30 to 60 people are killed by an injection of 10 cm of a 30% phenol solution into the heart. That number includes about 4–6 Poles who are political prisoners or on the verge of death. Jewish prisoners are admitted only when their condition is not serious. The injections are administered by SDG Josef Klehr, a shoemaker by trade, and Mieczysław Pańszczyk,24 an orderly and real scum. It takes victims fifteen seconds to die. TB patients are eliminated without scruple. The highest death rate is for the diarrhoea ward and the second highest is for the typhus ward.

The second stage of the hospital’s operations came in 1943 and early 1944, when the situation stabilised in a favourable sense. A report written by the camp resistance organisation on 23 April 1943 says that the number of inpatients was 2,431, and most of them were Jewish.

There are very many cases of erysipelas and diphtheria, but fewer patients with typhus. . . . Since the establishment of the men’s camp as many as 78,000 prisoners have been registered. Some of them have already been gassed, shot, killed with injections, beaten to death, or have died of natural causes. No records are made of those Jewish and Polish arrivals who were not registered and sent straightaway to enjoy the gas chambers and crematoria. . . . Auschwitz I, the main camp, holds about 8,000 prisoners. The overall count, including Birkenau, is 34,000. There has been a considerable drop in the death rate, to about 36 per day, including about 10 jabbed.

A kite dated 12 May 1943 says that the hospital has expanded, with a new block, No. 9:

There are 2,300 patients, not counting women, Roma, and Birkenau prisoners. The Roma camp25 is being ravaged by typhus. Some 30 die every day.

The third phase, which lasted until January 1945, was the time when the hospital really became what it should be: a place that saved prisoners’ lives and provided treatment for them.

A prisoner’s fate was sealed as soon as he arrived in Auschwitz. Having passed through the gate, he was immediately informed his life expectancy did not exceed three months. He was transformed into a number waiting for its turn to the crematorium. The camp was a death factory and the clatter of its machinery was deafening. If you were not crushed by its mills, it was by pure chance. A prisoner lived in utter deprivation and was not given even the barest necessities to survive. Forced to do hard labour and dispirited by the hopeless situation, a prisoner became emaciated and turned into a Muselmann: a prostrate, physical and mental wreck, totally apathetic even in the face of death, which he accepted without protest, because he was already dying and too weak to resist.

It was by sheer chance that an Auschwitz prisoner did not die within the first few months of incarceration. Only those could adapt to the camp conditions who were appointed to a function, worked indoors, had an opportunity to get extra food rations etc. However, the group of such prisoners was negligible. Some transports, even those with thousands of people, perished without a trace, without a single surviving witness. Adaptation was easier for specialists in a trade and qualified workers who were needed for the camp to function and expand. The number of casualties was the highest among the educated classes: office clerks, university tutors, and doctors, who were easily overwhelmed by the back-breaking work, the cold and the inadequate clothing, the hardships of living in barracks and having to fight for food, the blows to their human dignity, physical abuse and mental torment.

Initially, the hospital did not employ prisoner doctors. Moreover, many of them were detained or held hostage in retaliation for participating in the Polish resistance movement and were killed by the Gestapo after a short period of incarceration; such was the fate of Drs Czesław Gawarecki, Wilhelm Türschmid, Adam Przybylski, Marian Gieszczykiewicz, Witold Preiss, and Henryk Suchnicki. Some doctors did not survive because of the harsh conditions of the camp. Therefore, initially the hospital staff were non-specialists with no medical training, for instance German criminals wearing a green triangular badge.26 They worked as block elders or orderlies. A small group of Polish political prisoners who were employed as orderlies or could practise medicine illicitly did not play a significant role until the second half of 1942. Up to that time, all their efforts were thwarted by the caucus of green triangles serving time for criminal offences and co-operating with the SS men.

Like most other Nazi German concentration camps, Auschwitz witnessed constant attempts by the political prisoners, who wore a red triangle as their badge, to take over functionary offices. This plan was harder to implement in Auschwitz than in Dachau, Oranienburg, or Buchenwald, because from the very outset the SS strengthened their grip over the camp by giving the most important posts, those of camp elders, Kapos, clerks, and block elders, to German criminals. When Auschwitz was established on occupied Polish territory,27 90% of its inmates were Poles, and the SS encouraged the German functionaries to give free rein to their basest instincts and kill Polish political prisoners. It was extremely difficult for a Polish political prisoner to get a functionary’s post: he had to be smart, speak fluent German, and know which strings to pull. Every Polish functionary was always closely watched by the SS men, the German functionaries, and the Gestapo’s informers. Also, he was more harshly judged by Polish fellow prisoners, who expected him to protect his compatriots. No wonder many functionary prisoners of Polish origin could not bear such a conflict of loyalties and lost their position. Some were so lenient and helpful for their fellow prisoners that consequently they were punished either by having to join the penalty unit or they were put in the Bunker,28 where they soon died. Some forfeited their functionary armbands and had to do hard labour again. Others became oblivious of their duty to their incarcerated countrymen and cared only about their own comfort, remaining indifferent to those in need, or they broke down emotionally and resorted to the malpractices of the criminal prisoners.

Like the kitchen, storerooms, offices, political department, and personnel department, the camp hospital offered jobs that were vital for the task of saving prisoners’ lives and working on their behalf. The hospital took in those who were completely exhausted and in a very serious condition. It was considered a last resort, because everybody realized that very few prisoners got better and left the hospital on their own two feet. When a prisoner saw that he was no longer able to stand up during roll call and go to work, he had no option but to report to the dispensary.

Selection for admission was exceptionally strict and inhumane. In the first stage of the camp’s operations, the procedure was as follows: after the evening roll call, on hearing the command “Arztvormelder antreten!” block elders dragged those who were on their last legs before the Rapportführer,29 who whacked the wretches with his club and kicked them, sent several of them back to the barracks for the working units, and handed over the lucky few to the medical personnel, who took them to the dispensary. Having been duly entered in the records and stripped of their regular camp gear, they had to be seen by an SS doctor, who never examined them but only offered a peremptory diagnosis and decided whether they should be admitted or not. He took the opportunity to select some of the prospective patients for a phenol jab in one of the adjacent rooms. Those who were not admitted were sent back to their barracks and work, sometimes having received some treatment in the dispensary. Those admitted were allocated to a particular ward and went through the ordeal of a cold bath, disinfection and removal of their head and body hair. Then their personal details were registered and finally they were allowed to lie down on a hospital bunk bed.

Only the temperature charts and medical records showed that the establishment was a hospital, as there were no doctors, no medicines, but plenty of lice, fleas, and bed bugs. The meagre food rations for the patients were made even smaller by the dishonest staff, and the floor and toilets reeked of bleach. An additional harassment was the strict discipline. Though all representatives of the medical profession are expected to protect the sick, the most terrifying moment for the patients was the arrival of an SS doctor in the room. His appearance spelled danger—a choosie for the gas chamber or a jab. Even if an inpatient survived the hospital hardships and his body beat the illness, discharge involved more risks, such as being assigned a new job, which was done by Arbeitsdienst.30 Of course the worst units, where the prisoners had the hardest tasks, were always short-staffed, because the number of labourers grew smaller day by day. And so, many convalescents had to join the most infamous commandos. To and fro on the switchback from the working units’ barracks, to the hospital and its staff, and back to the workers’ block again—which was the best-case scenario—a prisoner could either be helped by his fellow inmates, left to his own devices, or harassed. The hospital staff witnessed the whole of his journey and were aware that death was his travelling companion.

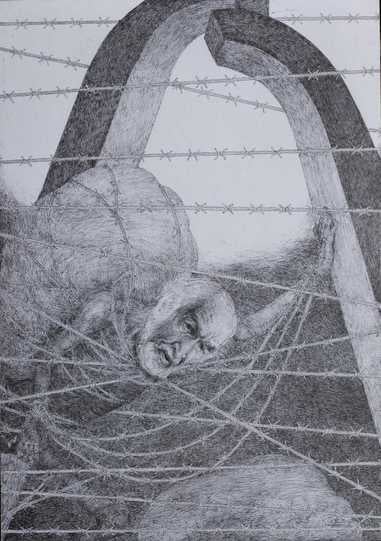

A Face Behind the Barbed Wire. Artwork Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click to enlarge.

The Germans envisioned concentration camps as conglomerates of prisoners who, having received a registration number, turned into passive robots with no personality, functioning according to a set pattern. A prisoner was to work automatically, doing everything on the double, eating automatically, and proceeding in an equally mechanical way when going to sleep, writing letters, killing lice, getting up at a functionary’s call or whistle, making his bed, standing in a line at a roll call, taking off his cap in front of an SS man, always answering “Jawohl!” upon hearing a command, evacuating his bladder and bowels in a fraction of a second at a set moment and in a designated place.

For the German SS, the ideal situation was to have such robots, or indeed whole blocks, working units, or camps of them. Any transgression against the prescribed routine was viewed as a crime for which a prisoner was punished with violence and molestation. A man who had been turned into a number was not allowed to think, because his thinking posed a threat to the camp. For instance, a mere chat about an escape was severely punished, even if no preparations had been made.

A prisoner’s ability to discard the mental burden of incarceration, even temporarily, and to release the tension he felt while performing any activity whatsoever in the camp was in itself a huge success which was attained gradually and painfully in his first, most difficult period of adaptation. He had to invest plenty of time and effort to get his bearings, and sometimes it was too late for him to make use of his camp experience: he may have already depleted all his strength and irreversibly fallen into apathy. This is why it was crucial for every new arrival to find a helping hand right from his day one in the camp. Such support could only be provided by the more experienced veteran prisoners.

From the beginning of the camp’s operations, it was the ambition of political prisoners to uphold their ethical guidelines, and one of them was to help a fellow inmate. This rule was followed initially by those who had met before, either as free people or in jail, or during transportation, and formed ties of friendship and reciprocal kindness. Mutual support was observed between relatives, but also between prisoners who had attended the same school, lived in the same town or village, been members of the same resistance organisations, political parties or clubs. Many prisoners survived thanks to the coordinated effort of the former inhabitants of their hometowns, places like Kraków, Tarnów, Nowy Sącz or Bochnia. Those informal self-defence and self-help groups, whose only means of relief were a chunk of bread, a bowl of soup, a pair of shoes, a piece of good advice, or an assignment to a light work commando, wanted to thwart the Nazi German plans to annihilate prisoners and indeed saved each other’s lives. Step by step, Polish political prisoners were turning into a stronger and stronger group of influence, shifting their focus from the interests of pre-war local communities to the wellbeing of the whole nation and the international situation, and showing more ideological engagement. At that time, the camp was taking in prisoners not only from Polish territories, but from other countries too. Some groups of prisoners considered it imperative to give functionary positions to ethnic Poles. Yet many prisoners, from Poland (such as Józef Cyrankiewicz and Tadeusz Hołuj) and other countries (Austria, Germany, France, the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia), held leftist views31 and prevailed with their idea of having functionaries of different nationalities. Soon afterwards the camp resistance movement was formed in order to defy the SS and its toadies.

With its Polish prisoner doctors, nurses, and clerks, the prisoners’ hospital played an important role in this battle. Thousands of Poles owe their lives to the fact that Polish orderlies started to work in the dispensary already in 1941. For instance, those prisoners who were important figures in certain political circles were admitted to the hospital on the sly, not having been examined by a Lagerarzt. The lab staff wrote fake results for medical tests in order to protect prisoners. Similarly, the radiologists did not release X-ray diagnoses that would have spelled death for the patients in question.

Gradually, the hospital was turned into a place whose main objective was to save lives. Almost all the jobs in it, such as the orderly, toilet attendant, washroom attendant, janitor, clerk, block elder, nurse, doctor, and pharmacist, were imperceptibly taken over by political prisoners, and 90% of the staff were Polish. Even the most menial jobs were held by the members of the educated classes, including physicians and medical students.

When run in a conscientious way, the hospital could counter the plans of the SS, while the sundry blows targeted at prisoners were sometimes successfully deflected or their consequences alleviated. The politically aware hospital management co-operated with the political leaders among the prisoners, while the camp functionary jobs of the Kapo, block elder or clerk, went, little by little, to prisoners with no criminal record, who realized what their role was. Close contact was established between the hospital and the kitchen, the workshops, prisoners working in the political and personnel departments, and even with Block 11, that is Death Block. The network of connections reached further out, to Birkenau, with its men’s camp, women’s camp, and Roma camp, as well to Monowitz and other sub-camps. The main outcome of these joint efforts was an improvement in cleanliness and hygiene in all the camp sections, and especially in the hospital. An unauthorised measure was implemented to install running hot and cold water facilities in the hospital washrooms, which made it possible for inpatients to take regular baths. The rules were changed to keep the toilets open all day long. Fresh straw was put into the patients’ mattresses a couple of times a year, and new blankets and bed linen were acquired. It was the ambition of the block elders and orderlies to keep the wards clean and the floors well-scrubbed, and to repaint the bunk beds regularly. Thanks to frequent, efficient disinfection and application of insecticides, the lice, fleas, and bedbugs were eliminated.

Patients received better food thanks to artful schemes carried out in the camp kitchen and provisions pilfered from the SS storerooms. No longer were their rations depleted: they got what was due, and sometimes convalescents were given extra rations, as they were supposed to go back to work. Also contacts with the parcel room proved to be of utmost importance, and almost every day the prisoners who worked in the camp slaughterhouse illicitly sent over considerable amounts of raw and processed meat they had pinched. During the last months of 1944 these parcels reached hospital Block No. 25 thanks to the help of the prisoners who had jobs in the political department.

The pharmacy held a considerable stock, so the patients could be treated in a more or less standard way. Many medicines were spirited away from the SS pharmacy and its storage rooms to replenish the supplies of the prisoners’ hospital. Considerable quantities of medications found their way to the wards from “Kanada.”32 Finally, some medical supplies were smuggled into the camp from Kraków,33 such as typhus vaccines provided by the Odo Bujwid Inoculation Institute34 or medicines that had been delivered to the Main Welfare Council35 by Swiss pharmaceutical companies. Survivor Edward Biernacki, camp No. 1802, now deceased, dispatched the following report on behalf of the camp resistance movement:

Dear Friends, as spokesman for all those who had been incarcerated behind the barbed wire fence of the concentration camp during this reign of terror, and a beneficiary of the services rendered to Poland by her bravest sons and daughters, I’m sending you our heartfelt thanks for your kindness and the help we’ve been receiving in this difficult, indeed critical time. Rest assured that your effort is never wasted and that very many people have been saved thanks to it. In June, July, and August, I managed to transfer to the hospital about 7,500 cm of injections (glucose, calcium, vitamin C, Septazin, Propidon etc.) as well as 70 series of the typhus vaccine. You have lots of collaborators in other places too and the results of this joint work are definitely impressive. You can be sure we shall not frustrate your hopes and plans. May God reward you amply for your dedication and support. Signed, Edward Biernacki, No. 1802.

The secret route for smuggling medicines was mapped out so meticulously that in the second half of 1944 it was possible for the parcel room to receive boxes containing as much as 5 or 10 kilos of pharmaceuticals. They were addressed to deceased prisoners, so each contraband parcel was intercepted before its contents could be officially checked. Then it was handed over to the Polish doctors in the hospital. The pharmacy in Auschwitz I (the main camp) became the distribution point for the medicines subsequently doled out to the women’s camp and the sub-camps. The scheme, which involved dozens of prisoners and a network of outside helpers, had to run like clockwork: if the SS had discovered any traces of such conspiracy, all the participants would have ended up in the Bunker and sentenced to death. An illicit report dated 20 January 1944 and smuggled out by the camp resistance movement explains the details of how parcels with medical supplies were to be posted:

We suggest a different way of dealing with medicines, that is proprietary drugs, not vaccines 13 and 1. Consider the following. People from Oświęcim or Zator36 can post carefully packed medicines, naming a phoney addressee “Häftl. Nr. 78825 Śliwiński Stefan geb. 12.1.1912 Bl. 25 Auschwitz Post O/S.37 We will intercept such parcels before they are checked. Even if such a parcel is discovered, the risk is negligible. Send parcels twice a week, with calcium, strychnine, Tonophospan,38 cardiac medicines, Prontosil39 tablets and ampoules etc. Remember to use that particular name and be careful while dispatching the parcel. It won’t be inspected on the way, the checkpoint is in the camp. So if you think this is feasible, go ahead. We are ready to receive the parcels and waiting for them. If you think it’s more convenient to send them from Kraków (but what about the border and the customs?)40 you can try once a week from there and the other time locally, just use the same camp number and name.

One of the transit points for medications and illicit messages smuggled into Auschwitz was the Raisko camp farm.41 The couriers were three women: Helena Płotnicka, a resident of Przecieszyn,42 her daughter Wanda Płotnicka, and Władysława Kożusznik. At night, they would sneak up to the utility buildings and drop the medicines, food, and secret correspondence through a half-open window. The risk of getting caught was considerable since the SS quarters were close by and the area was patrolled by guards with dogs: it was within the camp’s Interessengebiet, a special zone around Auschwitz which civilians could not enter on pain of death. The consignments delivered during the night were picked up in the morning by prisoners working there and kept hidden on their body and in their trouser-legs for the entire working day. A prisoner who was caught smuggling anything was killed on the spot. Yet the medicines had to pass through the camp gate and reach their destination, which was the hospital. There the medicines were pulverized and administered to the patients, unnoticed by any third party, and even the patient did not know what he had been given. This procedure was implemented in a concentration camp, where every move was watched by hundreds of eyes and where you could not find a secluded place. Of course, several people were caught and punished or killed. For instance, Jan Winogroński, camp No. 8235, now deceased, spent three months in the Bunker of Block 11. Kazimierz Jarzębowski managed to escape from the camp, but was captured and killed on 20 August 1943. Helena Płotnicka was arrested in February 1943 and incarcerated in Block 11. Having been maltreated during the investigation, on 17 March 1944 she was killed in the women’s camp as political prisoner No. 65492. Her daughter Wanda Płotnicka managed to escape.43

Summing up, in the third period of the camp’s operations the hospital was run competently and efficiently. It had several wards: surgery, observation, internal medicine, infectious diseases, TB, and bowel problems. They were staffed by recognized specialists. The hospital started to function in a markedly altered way, because it not only treated the patients and protected them from the SS, but also looked for appropriate jobs for convalescents. Conversely, the hospital was the best place to turn to if you wanted to get a better job assignment, avoid being transferred to another camp or getting punished.

The politically aware Polish doctors recognized the need to get a foothold to influence the Nazi personnel of the camp: the Standortarzt,44 those who were appointed Lagerarzt, the SDG, the commandant’s office, and the political department.

They did it all by fair means or foul, and their personal contacts were used for the common good. Trusting the Polish medics, some of the SS doctors started to learn from them, for example the SS doctor Werner Rohde45 perfected his professional skills in internal medicine under the guidance of Dr Roman Łaba (now deceased), who used to live in Przemyśl. The SS functionaries could be bribed with money, alcohol, or various favours. Sometimes prisoners supplied them with medicines that were not provided by the SS hospital, or offered them morphine. Many high-ranking SS officers preferred to consult the Polish doctors on the sly. Therefore, later on they could be persuaded or blackmailed to change, or dissuaded from implementing decisions that were harmful to prisoners. The hospital was intentionally turned into a hub of the camp resistance movement, whose leaders were Józef Cyrankiewicz,46 Tadeusz Hołuj,47 Hermann Langbein,48 and Karl Lill.49 The underground resistance movement in the camp advised Dr Władysław Fejkiel, a veteran prisoner, to accept the post of head of the hospital.

To some extent, the successes of the Polish medics were due to the German setbacks on the Eastern front and the modified policies of the Third Reich: prisoners were to replenish the dwindling ranks of native German workers in the Nazi war economy. The hospital served as a starting point for many escapes from the camp and dispatched messages that were later broadcast by the radio stations in London and Moscow, thus revealing the true face of fascism to the international public.

During the last two years of the camp’s operations, the hospital became the headquarters of the international resistance organisation. It has to be stressed that when it was managed by Polish political prisoners, patients were no longer selected for death by gassing or phenol injections. The mortality rate dropped to one-digit figures, and so the hospital became a place which really saved lives.

***

Translated from original article: Kłodziński, S. “Wkład polskiej służby zdrowia w ratowanie życia więźniów w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1961.

Notes

- I.e. excluding those who were never registered.a

- This was the official figure estimated in the years immediately after the war. Currently it is estimated that 1.1 million died in Auschwitz. The death toll includes 960,000 Jews (865,000 of whom were gassed on arrival), 74,000 ethnic Poles, 21,000 Roma, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and up to 15,000 other Europeans. Cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auschwitz_concentration_camp; http://auschwitz.org/en/history/the-number-of-victims.a

- This company was founded by Bruno Tesch and P. Stabenow in 1924 and registered in Hamburg. It manufactured pesticides. The company’s management knew their product Zyklon B, originally a pesticide, was being used to kill humans in the gas chambers, because they patented a new version of Zyklon B after removing the pungent warning odour from its original chemical composition. After the war, Tesch and other company associates were put on trial and charged with war crimes. Tesch and his plenipotentiary Karl Weinbacher were found guilty, sentenced to death, and hanged. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tesch_&_Stabenow.a

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Höss (1901–1947). German war criminal, commandant of Auschwitz. Wrote his autobiography while awaiting execution following his trial and conviction. Presumably Kłodziński is referring to the original German edition of the memoirs, or to its Polish translation. English version: Commandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolf Hoess (translated by Constantine Fitzgibbon, Phoenix, 2000).a

- The author’s attempt to present his numerical estimates, which are also hard to verify, as percentages, results in erratic and chaotic data which cannot be corroborated by sources. The editorial team of the Medical Review Auschwitz project decided to leave the numbers and percentages as printed in the original text, whereas the introductory note to the translated article and the footnotes clarify some of the problems caused by the author’s numerical data.c

- Jan Olbrycht (1885–1968), Polish forensic scientist, professor of the Jagiellonian University, Auschwitz and Mauthausen survivor and a major contributor to the Polish investigation of the Nazi German crimes committed on Polish territory. See his article “A forensic pathologist’s wartime experience in Poland under Nazi German occupation and after liberation in matters connected with the war” on this website.a

- After the German Revier (infirmary).a

- Dr Władysław Fejkiel (1911–1995), Polish physician, Auschwitz survivor No. 5647. The English version of his article on the medical service in Auschwitz is due to appear shortly on this website.a

- Polskie Towarzystwo Lekarskie.a

- Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler took the decision to launch the Aktion 14f13 programme in the spring of 1941. Before gas chambers large enough to handle mass killings were built in the concentration camps, victims were sent to their deaths in killing centres such as Hartheim, Bernburg, and Sonnenstein. Cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Action_14f13.a

- The SS Death’s Head Units (so called after their skull and crossbones badges) were special units set up to run the concentration camps. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS-Totenkopfverbände.a

- An SDG was a medical orderly in a German concentration camp.a

- For details see the article by Tadeusz Paczuła (English version “The organizational structure of the prisoners’ hospital at Auschwitz I”) on this website.a

- Reichsdeutsche were German citizens (as opposed to ethnic Germans who were inhabitants of German-occupied territories , who were called “Volksdeutsche”).a

- A German SS physician on duty in a concentration camp.a

- The Political Department.a

- SS-Unterscharführer Josef Klehr (1904?1988), transferred to Auschwitz in 1941 and worked there as a medical orderly in the prisoners’ hospital. He was renowned for killing prisoners with a phenol injection into the heart. He devised ways to optimise the speed of the killing process, such as experimenting with the positioning of prisoners before their injection. He was famed for his sadistic cruelty. As told by Witold Pilecki, who had first-hand knowledge of Klehr’s operations in Auschwitz, “Klehr used to murder with his needle with great zeal, mad eyes and a sadistic smile, he put a stroke on the wall after the killing of each victim. In my times, he brought the list of those killed by him up to fourteen thousand and he boasted every day with great delight, like a hunter who told of the trophies of the chase.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josef_Klehr.a

- SS-Oberscharführer Herbert Scherpe (1907–1997), Nazi war criminal, SDG in Auschwitz-Birkenau. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Scherpe.a

- SS-Unterscharführer Emil Hantl (1902–1984), war criminal. Worked in Auschwitz from August 1940 to the camp’s evacuation in January 1945, initially as a guard and later as an SDG administering phenol jabs. Arrested in 1961, tried by a West German court in Frankfurt in the second Auschwitz trial, convicted and sentenced to three and a half years in prison. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emil_Hantl.a

- The Hygiene-Institut der Waffen-SS, founded in 1939 and originally known as the Bakteriologische Untersuchungsstelle der SS, had a number of aims, one of them being to develop medicines and vaccines for the control of epidemics. These substances were tested on concentration camp prisoners artificially infected with the disease and given a medication which was tried as a prospective treatment. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hygiene-Institut_der_Waffen-SS.a

- The Germans kept meticulous daily records of the number of inmates in their concentration camps. The figures—of live inmates plus those who had died during the previous 24 hours—had to tally, and this was checked during the morning roll calls.a

- These death camps were built later, in July 1942 and March 1942 respectively.a

- Presumably this report was a kite (smuggled message) addressed to secret suppliers outside the camp, perhaps the Polish Red Cross. See the biographies of Dr Szlapak and Teresa Lasocka-Estreicher on this website.a

- Mieczysław Pańszczyk, an Auschwitz inmate (No.607), who arrived on the first transport and became a “jabber.” He was lynched by other prisoners.a

- In 1942, Heinrich Himmler ordered the deportation of all Roma to Auschwitz. As a result of this ruling, the Roma family camp known as the Zigeunerlager, which existed for 17 months, was set up in Auschwitz-Birkenau sector BIIe. Circa 23,000 men, women, and children are estimated to have been imprisoned there. About 21,000 died or were murdered in the gas chambers. Since they were treated as “asocial” prisoners, they were marked with black triangles. A series of camp numbers, prefaced with the letter Z, was given to them and tattooed on their left forearm. The Roma Camp was closed down on the night of 2 August 1944. That night at least 4,000 men, women and children were killed in the gas chambers. Cf. http://auschwitz.org/en/history/categories-of-prisoners/sinti-and-roma-gypsies-in-auschwitz/25.a

- In the German concentration camps prisoners were categorised and had to wear a badge on their gear in a special colour and shape depending on their category. Criminals wore a green triangle. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_concentration_camp_badge.a

- In fact Auschwitz and its environs were within the Polish territory directly incorporated in Germany.a

- The Bunker was a dungeon in the cellar of Block 11 (Death Block). Very few prisoners sent to the Bunker came out alive. http://auschwitz.org/en/museum/about-the-available-data/buch-der-strafkompanie.a

- German for “report leader”, i.e., the SS man conducting the roll call.a

- Arbeitsdienst, literally “labour service,” was a German institution organising young people’s voluntary service. When Hitler came to power, it was transformed into Reichsarbeitsdienst (“labour service for the German Reich”). During the war it was compulsory for all young men and women between the ages of 18 and 25 to work prior to military service. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reich_Labour_Service.a

- There were several resistance groups in Auschwitz, and not all of them (not even the largest ones) “held leftist views,” but of course such information would not have been passed by the Communist censor at the time this article was published. Cf. http://www.auschwitz.org/historia/ruch-oporu/zorganizowana-konspiracja.a

- “Kanada” was a special storage facility. On arrival at the ramp, Jewish prisoners had to strip and leave their clothes and belongings behind before being killed in the gas chamber. Later their belongings were searched by a commando of prisoners who had to look for gold and other valuables concealed in the discarded items. The valuables were then stored in the Kanada warehouses, while the discarded items were incinerated in a special facility. The SS guards shot any prisoner caught stealing anything from the piles of discarded clothing. For more information and a bibliography, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanada_warehouses,_Auschwitz.a

- See the biographies of Dr Helena Szlapak and Teresa Lasocka-Estreicher on this website.a

- Odo Bujwid (1857–1942), Polish physician and bacteriologist, student of Robert Koch, pioneer of Polish bacteriology. His institution in Kraków producing vaccines operated continuously from 1891 to 1951. https://khm.cm-uj.krakow.pl/historia-polskiej-bakteriologii.a

- Rada Główna Opiekuńcza, the Main Welfare Council, the only Polish charity organisation recognised by the Germans in occupied Poland.a

- Oświęcim and Zator are places in the vicinity of the Auschwitz site.a

- German inscription reading “Prisoner No. 78825, Śliwiński Stefan, date of birth 12 Jan. 1912, Block 25, Auschwitz, Upper Silesian Postal Region.”a

- Tonophosphan is a drug for the treatment of bone disorders such as rickets, and to help broken bones heal. It is now used for the treatment of animals.a

- Prontosil—sulphonamide drug manufactured by the German company Bayer for the treatment of fungal skin infections. Rudolf Franck, Moderne Therapie in innerer Medizin und Allgemeinpraxis. Handbuch . . .. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1941 (12th edition).a

- The German occupying authorities put Auschwitz and its environs within the territory directly incorporated in Germany, while the city of Kraków was in the so-called Generalgouvernement (the rest of German-occupied Poland, administered by Hans Frank), so anyone who wanted to make the 66-km (41-mile) journey had to reckon with crossing a border and going through customs.a

- The Raisko sub-camp was 3 km (1.87 miles) away from the main camp of Auschwitz. It was set up on the area of the village of Rajsko after the eviction of its inhabitants, comprised a farm with a horticultural experimental station and the SS Institute of Hygiene. http://www.auschwitz.org/historia/podobozy/raisko.a

- Przecieszyn, a small place in the environs of the camp, 5 km (3 miles) away from Rajsko.a

- Wanda’s two-month confinement in Auschwitz is mentioned in the 2014 edition of the local paper, which says that she was released after the investigation. Her mother is not mentioned as a prisoner of Auschwitz. See https://www.gbprzeciszow.pl/wgp/wiesci/2014-pazdziernik-grudzien.pdf. Another online source confirms Helena’s imprisonment in Auschwitz, but says she died there of typhus: https://www.powiat.oswiecim.pl/aktualnosci/pamiatki-po-bohaterskiej-mieszkance-przecieszyna-w-muzeum-pamieci.b

- The garrison doctor, i.e. the camp’s chief physician. a

- SS Dr Werner Rohde (1904–1946), Nazi German war criminal (name misprinted in the Polish text). Held a physician’s appointment in Auschwitz-Birkenau and later in Natzweiler-Struthof. Carried out death selections. Put on trial after the war before the British military court, convicted for war crimes, sentenced to death and hanged. Hermann Langbein, Menschen in Auschwitz, Frankfurt-am-Main, Berlin, and Wien: Ullstein-Verlag, 1980, Ernst Klee, Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich: Wer war was vor und nach 1945, Frankfurt-am-Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2007.a

- Józef Cyrankiewicz (1911–1989)—a prominent member of the PPS (Polish Socialist Party) before the war; involved in the wartime underground resistance movement both at liberty and when held in Auschwitz. After the war Cyrankiewicz joined the PZPR (Communist) Party and served for many years as Prime Minister of People’s Poland. For more details, see the biography of Dr Helena Szlapak on this website.a

- Tadeusz Hołuj (1916–1985), Polish writer, journalist, and politician. Veteran of the Polish defence campaign of September 1939 and member of the resistance movement. a

- This name is misprinted in the original article. Langbein survived and authored several books on Auschwitz and Hitler’s Germany (see Comment 45).b

- Karl Lill (1908–1977), political prisoner and survivor of several Nazi German concentration camps including Auschwitz (No. 60356), where he worked as the secretary of the SS hospital. After the war he lived in East Germany and was a witness in the Frankfurt trial of the SS staff of Auschwitz. http://www.auschwitz-prozess-frankfurt.de/index.php?id=81.a

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Marta Kapera, the translator of the text; c—note by the Editorial team, courtesy of Teresa Wontor-Cichy, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.