Author

Jan Nowak, MD, b. 1908, physicina, survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau (prisoner No. 17380), Majdanek, Gross-Rosen (prisoner No. 29040), and Leitmeritz. Member of the underground resistance movement and prisoner-doctor in Auschwitz, witness in the Auschwitz trial of 1947.

Stefania Perzanowska, MD, 1896–1974, participant of the Polish WW2 anti-Nazi resistance movement, survivor of Majdanek (camp No. 235), Auschwitz-Birkenau (No. 77368), and Ravensbrück (No. 107185), prisoner-doctor and main organiser of the women’s camp hospital at the Majdanek concentration camp.

Professor Michałowicz in the Nazi German concentration camps

by Jan Nowak

Professor Mieczysław Michałowicz died on 22 November 1965. He was one of the most brilliant and popular physicians of our time, the doyen of Polish paediatricians, holder of an honorary doctorate awarded by the Kraków Medical Academy, a member of many foreign medical societies, an outstanding scientist and thinker, a pioneer of the application of electronics and cybernetics in Polish medicine, as well as an unforgettable educator of numerous Polish paediatricians.

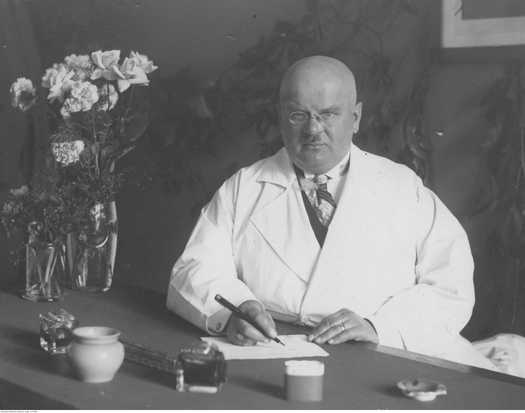

Prof. Mieczysław Michałowicz, ca. 1930-1931. Source: The National Digital Archives of Poland.

I was privileged to observe and admire his activities in the interwar period as well as during and after the Second World War. In this brief obituary I would like to give an account of his life during the dark night of Poland’s wartime occupation.

He was arrested in Warsaw on 11 November 19421 as part of a special operation targeted primarily against the Polish intelligentsia from all the pre-war progressive and left-wing organisations. Professor Michałowicz was a co-founder of the Democratic Party2 and his anti-fascist stance was all too well-known. As Rector of the University of Warsaw,3 he was against the racial discrimination (practised in the form of “ghetto benches”4), so his activities were all-too conspicuous to let him evade repression by the German occupying forces.

In the spring of 1943,5 after several months of imprisonment in the Pawiak jail in Warsaw, Michałowicz was sent to Majdanek concentration camp and initially placed in Field 3.6 However, we soon managed to get him moved to Field 1, where the central prisoners’ hospital was located. He was accommodated in Block 5 and remained under my care all the time. It was here that he contracted epidemic typhus,7 in the third week of his confinement in Majdanek.

Anyone who has been held in a concentration camp knows what this disease meant in the appalling conditions of prisoners’ lives. However, we also know that the will to fight our oppressor releases insurmountable resources of fortitude and courage in us; and prisoners’ willingness to make a sacrifice for fellow inmates was not unusual in the circumstances. This is what happened during Prof. Michałowicz’s illness. We managed to “organise”8 doses of glucose and strophanthin9 for him. We even smuggled in fresh white bread from the nearby city of Lublin with the help of dedicated people from the Red Cross under the leadership of Dr Christians.10 We were also supported by some Lublin activists, including Saturnina “Mateczka,” Malmowa,11 Antonina “Ciotka” Grigowa, Elżbieta “Elżunia” Krzyżewska, Hanna Huskowska and many others whose names should be made known to public opinion and whose merits should be recognised and rewarded.

There was a continuous stream of secret correspondence smuggled into the camp from Lublin by other civilian employees12 working on the extension of Majdanek, and thanks to this mode of communication with the free world I managed to provide effective treatment for Professor Michałowicz. The day he regained consciousness was a great moment for all the medical staff of the prisoners’ hospital. Our group of prisoner doctors, mostly Poles, was quite large, probably over 60.

Other problems concerning Prof. Michałowicz’s treatment was his obesity and serious complications, pneumonia and acute diarrhoea, which did not bode well for an almost 70-year-old man. But thanks to the good care of the nurse assigned to our block, the Slovak Jew Nikolasz Krauze, who followed all the prisoner-doctors’ instructions scrupulously, Michałowicz’s condition improved steadily.

Eventually, his condition was good enough for him to recover his speech. I remember that one day he asked me to bring him some “biological liquid”. After a discussion what he meant, we came to the conclusion that he wanted some milk or mineral water. We managed to get milk from Lublin: a worker constructing the drains in our barrack smuggled in a bottle of milk in the upper of his boot. We also managed to “organise” mineral water, which was provided by Jan Wolski,13 a fellow prisoner employed in the SS canteen.

Throughout the spring of 1943, our Professor was slowly recovering. In June, with the consent of the SS physician, we managed to organise meetings of the hospital staff during which Michałowicz gave lectures in German on various fields of medicine. These talks were very popular with our medical staff. I am still moved whenever I recall those moments when I accompanied him and carried his teaching aids, tables and charts for the lectures. And it is hard to give an unemotional account of the enthusiasm of the inmates who listened to him lecturing in the hated language of the oppressors. His talks were intended to enhance the quality of the medical care we provided, but also to stir our patriotic feelings, which was quite understandable in these conditions. For Prof. Michałowicz they were occasions to forget the terrors of the camp for a while, to break away from the horrifying reality of camp life.

Michałowicz felt he was very useful: he could teach others and share many of his humanitarian thoughts, which strengthened his fellow inmates and kept their spirits up. In our day-to-day life in the camp I had the opportunity to discover the Professor’s extremely rich and interesting personality. All of us admired his conviction that victory over fascism14 and the restoration of Poland was a certainty. Sometimes when we knew there was an impending threat hanging over us, he turned our attention away from gloomy matters, and for example, he’d start up a conversation on a scientific matter.

Thanks to our contacts with the Polish Red Cross in Lublin, we managed to obtain the camp authorities’ permission for him to see his wife on the Red Cross premises in the city. This meeting was a great experience for him and also for us, as he returned to the camp even more resolved to persevere; he told us the news about the Allies’ operations on all the fronts.

Majdanek was evacuated in the spring of 1944.15 We were transported to Gross-Rosen. After a period of relative “freedom” at Majdanek, which was on occupied Polish territory, with the SS discipline evidently getting slack, in the new camp16 we experienced physical hunger as well as hunger for any news we could get from the outside world. At Majdanek the outside information we had obtained had helped to keep our spirits up, but the grim new situation disheartened us, especially Prof. Michałowicz.

When new transports of prisoners arrived, particularly after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising,17 he would sneak out of the block unnoticed and, regardless of the danger, go to other blocks to obtain news from Warsaw and about his relatives.

In July 1944 we went through a particularly dangerous time, when following the assassination attempt on Hitler, the Germans launched an intensified reign of terror, especially against the Polish intelligentsia. The camp’s SS authorities established a Sonderkommando,18 which soon filled up with the most eminent prisoners. We had great trouble to keep the Professor from being sent to this commando.

Then there was another evacuation. Transports of healthy prisoners were constantly leaving. We also saw numerous transports from other camps, especially from Auschwitz, passing through our zone. In the evenings, we could hear the noise of the approaching front. Yet the SS orders were to keep us moving away from this front, which would bring us our liberation. The last transport of those who were unable to walk was to leave in February 1945.19 We tried to put Professor Michałowicz in this group, but he told us, “Whatever happens, I want to stay with you; you are part of my country. If I am to die, I want you to be with me.”

We left late in the evening of 9 February. The columns of marching prisoners were guarded by an SS escort with dogs. The barking dogs and the noise of SS guns shooting stragglers with no more strength to continue walking created a horrific cacophony beneath the dark, overcast sky. We were walking downhill towards the town of Gross-Rosen when we suddenly heard the rumble of aircraft engines. But shortly we were made to turn back for the camp.

There was widespread fear among prisoners that the camp would be bombed by German planes and the blame for the raid would be put on the Allies. The Professor came through this ordeal in good shape. The next day we marched out of the camp again. After a few kilometres, we were made to board a train made up of open freight carriages. For three days and three nights we travelled across Saxony without any food, and finally on 13 February, we reached Leitmeritz, which is north-west of Prague. Along the way, hundreds of bodies of prisoners who had died were thrown off the train.

Leitmeritz20 was a labour camp, a sub-camp of Flossenbürg. In the hills surrounding the camp there were factories producing spare parts for tanks. The Professor and the rest of us were accommodated in the camp hospital located in the old Austrian barracks. The camp held five thousand prisoners, but all the time new transports were arriving from areas under Allied fire. There were 1,500 patients in the hospital, including over 500 with typhus fever.

We soon established contact with members of the Czech resistance movement, and so we had information about the situation on the fronts. Our hopes of liberation rose. Unfortunately, in this hectic atmosphere there were numerous cases of epidemic typhus among the prisoner doctors who had not been infected before.

This camp started to be evacuated too, but one day in May there was an announcement that we were free. Professor Michałowicz and the other doctors went round the hospital with the good news. Everyone was delighted. On 8 May the staff of the prisoners’ hospital left the camp in the last transport. Only five doctors stayed behind to look after the rest of the patients. Everyone who was fit enough to walk decided to set off for the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.21 There we were given a welcome with white-and-red flags waving and reminding us of Poland. Professor Michałowicz seemed to be skipping along, rejuvenated and joyful. We spent three weeks in Prague. On 1 June 1945 we were back in Poland.

Recollecting Majdanek

by Stefania Perzanowska

Despite the strict segregation of the men’s and women’s sections of the German concentration camps, as well as the rigid prohibitions and severe penalties for prisoners who broke this rule, in all the camps male and female prisoners were in contact with each other.

So when the kapo of the Majdanek hospitals, whom everyone called “No. 1 Kapo,” came to me in April 1943 with the news that Professor Michałowicz had just arrived from the Pawiak Prison and that he wanted to see me, I had no problems to arrange a visit. I submitted an official request to the SS command of the camp to allow Michałowicz, a renowned professor of medicine, to come to the women’s hospital for a consultancy. I was banking on the fact that he was a professor would justify my request.

Indeed, two days later, Professor Michałowicz visited our hospital, assisted by an escort of SS men and “No. 1 Kapo.” The kapo quickly got rid of the SS men, so that we could talk freely, without any Germans assisting, and for quite a long time at that.

I had known Professor Michałowicz for a long time. I was his student at the University of Warsaw. I took the paediatrics examination with him. Later I used to see him at various scientific meetings and conferences, and at one time in Vienna before the war we had many occasions to chat. I was working as an intern in a clinic, and Professor Michałowicz came with his son for the Olympiad.22

When I saw him again at Majdanek, I was shocked by his appearance. A man who had always been corpulent and big was now so thin that his prison gear drooped down like from a clothes hanger and made him look even taller; his red, round face had somehow become elongated and was greyish pale.

My first impression of him was so strong and must have been so obvious on my face that Professor Michałowicz immediately started to reassure me that he felt well and was glad to have lost weight since now he was physically fitter than before and the “crash diet” had done him good.

As always, his face lit up with a smile. He was beaming with his unique, matchless vitality, optimism and cheerfulness against all the odds.

He asked about my family and personal matters, the details of my arrest and the beginnings of my confinement at Majdanek. He was interested in the female prisoners’ hospital, its staff and patients. As we were walking around the hospital blocks, he gave each patient a kind and sympathetic look.

He did not say a word about himself, and especially about his confinement in the Pawiak prison, giving me a gentle smile when I asked him about it. However, he spoke cordially and at length about his fellow prisoner-doctors in the Majdanek male prisoners’ hospital; they were so good to him and did their best to help him put up with the conditions in the camp. At the end of our first conversation, he declared emphatically, “Well, I tell you, my dear friend, I’ll be a professor of the University of Warsaw again, and you will see I’ll teach your daughter!” He remembered that I had a daughter who dreamt of studying medicine after the war.

Since I had already been in Majdanek for several months and was receiving parcels sent by my family, I could offer him a piece of hastily reheated meat and a white homemade bun, which he ate up, down to the last crumb. He was evidently starving after his detention in the Pawiak. Later, when we met in Ciechocinek23 after the war, he still reminisced about that treat, adding that he had commended my culinary talents to his wife, and that never in his life had he eaten such tasty meat. It was hunger that made him consider the meanest bite of meat an extraordinary delicacy.

Several days later Professor Michałowicz came to our hospital again, on the pretext of more medical consultations. Just like the first time, he was escorted by “No. 1 Kapo,” who told me that this time his visit could not be longer than an hour. The Professor had heard that Zofia Praussowa,24 a senator and well-known PPS activist, was being treated in our hospital. He was worried about her and wanted to see her. They were probably the same age and knew each other well, since Michałowicz had also been a PPS member of the pre-war Senate.

So I took him to the third hospital barrack, where Praussowa was at that time. It was touching to see how moved they were and immediately embraced each other. Hugging tiny little Zofia, the Professor showed his concern and said, “Now that we’ve met here, let’s not be so formal with each other from now on. Zosia, call me Mieczysław.” His words and gesture not only expressed his enormous cordiality, but also his care and concern for this emaciated, grey-haired woman.

So they were sitting on the bunk bed and talking about their families, reminiscing about their pre-war initiatives and undertakings; and they even began to plan what they would be doing after the war, in a free Poland. Two friends—advanced in years, former community workers—were passionately discussing all kinds of post-war opportunities, problems and issues. Professor Michałowicz was full of ideas and ready for future work, while Zofia, smoking one cigarette after another, bravely seconded him in those plans. There was something fascinating about this skinny couple crouched on the bunk and enthusiastically talking about something that was so uncertain. They were so absorbed in the discussion and so far away from the reality of the camp that I had to remind them twice that it was time for him to go back to his barrack.

Seeing that Zofia was a chain smoker, Michałowicz promised to “organise” some cigarettes for her. He kept his promise and on several occasions sent her boxes of cigarettes through our trusty inmates. He did not smoke himself, and it was easier to “organise” tobacco in the men’s field, and even have it sent in parcels. In fact, cigarettes were a valuable commodity that inmates could barter for something else. Evidently, the Professor preferred to have cigarettes smuggled in for his old friend.

After some ten days, he came to our hospital again, but only for a short while. He was in a far worse condition physically than before and a few days later he fell ill with epidemic typhus. I was very worried about him—and so, too, all his fellow inmates from the men’s section must have been—after all. he was 68! When he recovered, but was still too weak to walk, he often sent me kites,25 asking about people he knew and various camp matters. In fact we continued to use this secret type of correspondence afterwards.

In early February 1944, there was a transport of sick prisoners from Ravensbrück to our hospital. Professor Michałowicz sent me a kite asking whether Krystyna Dębowska, a former patient of his old patient, was on it. When I informed him that she was, he came to visit her. We again did the hospital round together and saw the patients in all the hospital barracks. He brought Zofia some cigarettes and listened to Krystyna’s story of her concentration camp experiences. He was interested in the condition of all the patients and other hospital matters. However, as usual he neither said anything about himself and nor complained about anything.

In late March 1944, some of the staff of the men’s hospital, including Professor Michałowicz, were transported to Gross-Rosen. On the day of their departure the weather was dreadful, a typical March day: it was sleeting, the wind was rattling the barbed wire, and the road through the camp was under a thick layer of slippery mud. I saw the Professor trudging along with difficulty, with the rain lashing his face and the wind blowing through his camp gear. He lost one of his clogs in the mud, and then the other one, so he was walking barefoot. As he passed the women’s field, he saw me and waved goodbye with his usual smile.

In April I left Majdanek for Auschwitz, in a group of patients and some of the hospital staff. After several months in the new camp, a prisoner doctor who had just returned from Gross-Rosen came to see me. Professor Michałowicz had asked her to pass on his regards and assure me that he was well, working in the hospital and—writing a textbook. I asked three times whether she had not got the facts wrong. But no, she was sure of the message and the Professor had even shown her the manuscript written on scraps of paper.

This is what Professor Michałowicz was like. With this inexhaustible vitality, intellectual prowess and the power of his mind, his incredible optimism and unwavering faith in survival, he was probably the only prisoner who could have decided to write a scientific textbook in a concentration camp. Deprived not just of the bibliography and references he needed, but certainly also of quiet and peaceful conditions, he was still able to completely isolate himself off from the nightmare of his surroundings and write a book, convinced that it would be very useful after the war. As we know, he completed it in a free Poland, again working as a senior academic and Rector of the University of Warsaw. Nonetheless, most of his two-volume textbook on the pathophysiology of childhood26 was written in Gross-Rosen.

After the war, I saw Prof. Michałowicz on many occasions. I remember him climbing the scaffolding of the Paediatric Clinic on Litewska in 1945. Over the past ten years I did not have the opportunity to meet him, except at the convention of former prisoner-doctors held in Warsaw in 1964. Outwardly, he had aged very much. When I went up to him, at first I thought that he had not recognised me though, as usual, he gave me a hearty smile.

During the lunch break I again approached him in the cloakroom and, knowing that he used a walking stick, offered him my arm to lean on while we were waiting for our coats. Then he said to me, “You may think that I have not recognised you, but I do remember you, my old friend, and the Majdanek women’s hospital, just as well as I remember your daughter, whom I examined in paediatrics some time ago.”

When our coats were brought, I asked whether he was going home for lunch and asked him to give my regards to his wife. He replied with his playful smile, “I’m not going home, I’m off to the city with my camp friends!” So we said goodbye and he left in a large company. That was the last time I saw Professor Michałowicz and that is how I remember him: forever young despite outward appearances, always cheerful and smiling, direct and cordial, with a friendly attitude to all, an endearing personality, a boundless store of empathy in his heart, and the vast intellectual resources of his mind.

***

Translated from original article: Nowak, J., Perzanowska, S., “Dwugłos o profesorze Mieczysławie Michałowiczu.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1968.

Notes

- The Germans apprehended him in his house at No. 23 on the Lekarska on the night of 10/11 November 1942.

- Stronnictwo Demokratyczne, a Polish centrist political party, founded on 15 April 1939. Mieczysław Michałowicz and Mikołaj Kwaśniewski were its leaders. Members of this party served in the Polish Underground State, which operated in Occupied Poland during the Second World War and had a domestic network of secret administrative, military, and judicial agencies in contact with the Polish government-in-exile. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_Underground_State.

- The head of a Polish university is known as its rector. Michałowicz was Rector of the University of Warsaw in 1930-1931.

- In the 1930s students belonging to nationalist youth organizations pressurised Polish universities to introduce a system of segregation known as the “ghetto benches,” whereby Jewish students had to take seats on benches reserved from them, away from non-Jewish students.

- Michałowicz was deported to Majdanek (Lublin) concentration camp on 25 March 1943.

- Majdanek concentration camp was established in 1942 and had an area of 30.6 ha (75.6 acres) consisting of five main sections known as fields with a total of 108 barracks, and two mid-fields. After May 1942, Field 3 accommodated Polish prisoners, and political prisoners from various countries after January 1943. A women’s camp operated in Field 5 until September 1943. From March 1943, children were also interned there. For more on Majdanek, see Józef Falgowski, “The SS health service at Majdanek” and Stefania Perzanowska, “The women's camp at Majdanek” on this website, and the Majdanek Museum website at http://www.majdanek.eu/en.

- Epidemic typhus is an acute infectious disease caused by Rickettsia prowazekii. The infection is spread by body lice. Symptoms include fever, chills, headache, vomiting, and a charatceristic rash. Not to be confused with typhoid. The Germans combated typhus epidemics in the concentration camps by killing infected inmates. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epidemic_typhus.

- In the concentration camp jargon, “to organise” meant to obtain something by illicit means, e.g., by stealing it from an SS warehouse.a

- Strophanthins are cardiac glycosides obtained from plants of the genus Strophanthus gratus.

- Ludwik Christians (1902–1959), Polish lawyer. Head of the Lublin municipal and powiat branch of the Central Welfare Council (Rada Główna Opiekuńcza) and the President of the Polish Red Cross for the Lublin district (1941–1944). Organised medical and food aid for Majdanek prisoners.

- Saturnina Malmowa (1907–1982) aka “Mateczka” organised aid for Majdanek prisoners, working with Antonina Grygowa (aka “Ciotka”) and Elżbieta Krzyżewska (aka “Ciocia”). Her contacts with prisoners began in January 1942 and continued until the camp’s evacuation. Apart from smuggling in food, medications, and secret messages, the aid also included arranging family visits for prisoners. For more information, see Stefania Perzanowska, “The women’s camp at Majdanek” on this website, and the Majdanek Museum website at http://www.majdanek.eu/pl/pow/saturnina_malmowa_-_cicha_bohaterka/50.

- “Civilian employees”—not concentration camp prisoners.a

- Jan Wolski, camp No. 49710, released on 9 Aug. 1943. See http://www.majdanek.eu/pl/prisoners-results?firstname=Jan&lastname=Wolski&day=&month=&year=&place-of-birth=&prisoners-search-submit=WYSZUKAJ.b

- Strictly speaking, the term “fascism” is a misnomer if applied to German Nazism, but it was commonly used in this sense in the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact countries.

- The final stage of the evacuation started on 19 March 1944.

- Originally established as a sub-camp of Sachsenhausen, Gross-Rosen was located on the territory of the German Reich.a

- The Warsaw Uprising in the summer of 1944, not to be confused with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943.a

- There was a disciplinary unit in Block 19 at Gross-Rosen for prisoners “requiring special supervision,” e.g., for escape attempts, rebellions, or sabotage. In August 1944 a special commando (Sonderkommando) was set up in it. Members of the intelligentsia and aristocracy, mainly Polish, were detained there. See http://www.schondorf.pl/wyprawy/kl-gross-rosen-kamienne-pieklo/.

- The evacuation took place on 8 February 1945.

- Leitmeritz was the largest sub-camp of Flossenbürg, Established on 24 March on occupied Czech territory to increase German war production. Of the 18,000 prisoners who passed through the camp, about 4,500 died due to disease, malnutrition, and accidents caused by the disregard for safety by the SS staff who administered the camp. In the last weeks of the war, the camp became a hub for death marches. The camp operated until 8 May 1945, when it was dissolved following the German surrender. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leitmeritz_concentration_camp.b

- The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German occupation of the Czech lands on 15 March 1939. Earlier, following the Munich Agreement of September 1938, Nazi Germany had incorporated the Czech Sudetenland territory as a Reichsgau (October 1938). During the War, the qualified Czech workforce and developed industry was forced to make a major contribution to the German war economy. The Protectorate’s existence came to an end with Germany’s surrender in 1945. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protectorate_of_Bohemia_and_Moravia.b

- The 1931 International Workers’ Summer Olympiad. Michałowicz’s only son, Jerzy Władysław (1903–1936), was a paediatrician, soccer player, and athlete.b

- Ciechocinek—a Polish health resort.

- Zofia Praussowa (1878–1945) was a Polish politician, and a PPS (Polish Socialist Party) member of the Polish Sejm (though not a senator as Pierzanowska writes). During the War she was a member of Związek Walki Zbrojnej—AK (the Union of Armed Struggle, later renamed the Home Army). In 1942 she was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned in the Pawiak prison, and later sent to Majdanek and Auschwitz.

- A kite is a secret letter smuggled into (or out of) a prison.

- Original title Patofizjologia i klinika poszczególnych okresów wieku dziecięcego, Warsaw: PZWL, 1950. The title is misquoted in the article as Fizjopatologia wieku dziecięcego.a

Unless noted otherwise, all notes by Anna Marek, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Maria Kantor, the translator of the article.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.