Author

Wacława Zastocka (1913–2002) served in the rank of captain in the office of the high command of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa), the main Polish underground resistance force, during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. Sources: www.1944.pl; krakowianie1939-56.mhk.pl.

Dr Zofia Franio deserves to be on the list of famous Polish physicians who have contributed significantly to their country’s medicine, history and social life within the last 60 years. She belonged to a generation “born in slavery and chained in . . . swaddling bands”;1 the highlight of her early life came in the autumn of 1918, when the dreams of several generations of Polish people were fulfilled and “Poland rose to live.”2 During World War II, Dr Franio rendered outstanding service to the underground movement and the struggle for Poland’s liberation.

She was born in Pskov, a governorate city of the Russian Empire, on 16 January 1899, as the youngest child of Michał and Władysława, a Polish family with strong patriotic traditions that fostered the spirit of struggle for independence and the memory of the national uprisings.3 Her father was a doctor who specialised in internal medicine and whose skills were appreciated both by the Polish and Russian inhabitants of Pskov.

Dr Zofia Franio. Source: Jerzy Piorkowski (1957), Miasto Nieujarzmione, Warsaw: Iskry; p. 66, via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1916 Zofia finished secondary school in Pskov, a girls’ school of the “Institute for Noble Maidens”4 type, earning a distinction: in the Russian Empire school-leavers who were top of their form were awarded a diamond ring. In the same year, she went to Saint Petersburg to study medicine.5 The large, settled and well-organised pre-war Polish community in St Petersburg was strengthened by over 60 thousand refugees from the Kingdom of Poland6 when the Russian military authorities forcibly evacuated millions during the Prussian offensive in 1915.7

The old Polish immigrants and the recent refugees engaged in an intensive programme of social and welfare work as well as political, cultural and educational activities. Zofia joined a group of patriotic Polish young people attached to the Roman Catholic Parish of St Catherine on Nevsky Prospect and in the Society of Friends of Polish History and Literature.8 Besides studying at the Psychoneurological Institute,9 she attended evening classes run by the Society, and was an avid student of Polish history and literature.

The outbreak of the October Revolution interrupted her studies and stay in the old capital of the Russian Empire. At 18, she went through the experience of what happened in the city after the cruiser Aurora fired the historic shot.10 In late 1917, she transferred to the Medical Faculty of the University of Rostov-on-Don. However, the following year Zofia returned to her parents’ house in Pskov, and along with a new wave of refugees made a perilous journey to Poland. Her parents settled in Mienia near Mińsk Mazowiecki. There her father started a medical practice and organised a hospital where he worked for the rest of his life.

On arriving in Poland, Zofia enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Warsaw. The post-war years were turbulent; the borders of the restored Polish state had not yet been established and fighting was still going on.11 Most students joined the Polish Army, considering the defence of the borders their first duty. Zofia reported to the sanitary service. She worked as a nurse on sanitary trains12 and in field hospitals; she served as the commanding officer of a sanitary station, providing dedicated nursing care for wounded soldiers. After the war,13 she returned to her interrupted studies at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Warsaw; additionally, she helped her father in the hospital in Mienia. In 1927 she graduated, obtaining a Doctoris Medicinae Universae14 certificate.

Service in the top military medical units had a huge impact on Dr Zofia Franio’s further life. In 1924, while still a student, she was introduced to the idea of training women to defend the country in the event of war; such a project was being promoted by women veterans of World War I and the Polish War.15 By this time, the Social Committee for Women’s Military Training16 had been founded and comprised the Polish Women’s Circle,17 the Polish Red Cross,18 the Polish White Cross,19 the Girl Guides of the Polish Scouting Association,20 the Association of Young Catholic Women,21 the Ladies’ Rowing Club,22 the Townswomen’s Circle,23 the Women’s Branch of the Sokół Association,24 the Women’s Trade and Accountancy Union,25 the Young People’s Rural Union26 and the Polish Riflemen’s Association.27 The organisers of these women’s groups wanted to recruit young women, especially university and college students and senior pupils of secondary schools, who were emotionally committed to the defence of the country. Mindful of her experience in the front-line sanitary service and knowing how useful a women’s service could be, Zofia wholeheartedly supported this idea and joined the pioneers of PWK,28 the Women’s Military Training Organisation. During her graduation year she attended women’s military courses and training camps. In September 1927 she was appointed commanding officer of the women students’ unit at the University of Warsaw and held this position for two years.

In 1927-1932 she was employed in the Second Internal Medicine Clinic in Warsaw under the supervision of Professor Witold Orłowski.29 In 1932-1935 she worked in the Infectious Diseases Observation Ward in St Stanislaus’ Infectious Diseases Hospital, and in 1935-1939 in the Municipal Outpatient Clinic for the Poor in the district of Wola and as a school doctor in this district. In addition, she put in a lot of hard work and commitment into the Sports Outpatient Clinic and in 1928-1935 was a member of the Scientific Council for Physical Education. She was also a PWK trainer and was promoted to inspector, the PWK’s highest rank. As its commanding officer, she ran camps and military training courses, courses for physical education leaders and first aid and medical rescue classes for women instructors to obtain professional qualifications to teach a new subject called “introduction to national defence,” which was put on the curriculum for Polish grammar schools in 1937.

When the General National Service Act of 9 April 193830 came in force, the Ministry of Military Affairs,31 the National Office for Physical Education and Military Training32 and PWK Headquarters drafted executive regulations for the Act, including regulations for a women’s auxiliary service. Dr Franio was tasked with drafting regulations for the examination and assessment of women’s physical and mental capacity to serve in the army. Her draft was approved by the Health Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs33 and published as the “San. 5. III. 1939” instruction, entered for official use by Schedule No. 0946-12 of 17 May 1939, signed by General Janusz Głuchowski,34 First Deputy Minister of Military Affairs.

From March 1939, PWK had the status of a high utility association35 and was appointed by the Ministry of Military Affairs to coordinate the activities of 57 women’s associations for self-defence training, national defence, and auxiliary service in the army. So in the last months before the war broke out, Dr Franio devoted all her free time to training and organising work for the Social Emergency Department at PKW Headquarters. All the time she was still working at the Wola Municipal Clinic for the Poor.

On 5 September 1939, the fifth day of the war, Dr Franio left Warsaw following orders for all the central offices to evacuate. She travelled to the staging point of the National Office for Physical Education and Military Training in Trawniki, and from there to Lwów.36 Although the military authorities had not issued a formal order for the women’s units in the auxiliary services, a volunteer women’s battalion had been formed in Lwów in the first days of the war under the command of Inspector Halina Wasilewska37 (daughter of Leon Wasilewski and sister of Wanda Wasilewska38). Dr Franio had originally been assigned to the Wilno37 women’s battalion, but now she stayed in Lwów due to the general military situation40 and because she would have been unable to reach Wilno.

When a PWK battalion was formed in Lwów, she organized a special recruitment commission for women volunteers and conducted medical examinations and assessments of the volunteers’ suitability for service according to the “San. 5. III. 1939” instruction. When German tanks reached the outskirts of Lwów, the battalion was tasked with the preparation of anti-tank incendiary devices. The girls in the battalion made Molotov cocktails in the sports hall on ulica Jabłonowskich under heavy artillery fire. Dr Franio joined them as a volunteer for the job.

When Lwów was handed over41 to the Soviet troops and the PWK battalion was demobilised, she stayed in the city for a few weeks, spending hours looking after her sick and weakened colleagues. I shall always be thankful for all she did for me when I contracted typhoid;42 she did not let me go to hospital but looked after me herself, doing her best to obtain medications and food in the extremely hard conditions. Also, she cheered me up and made me regain the will to live. As soon as I recovered, she left the city with her Warsaw team mates.

On arriving in Warsaw on 7 November 1939, she immediately reported for work as a physician at the Wola Municipal Clinic for the Poor. She contacted Maria Wittek,43 the head of PWK, and joined the underground resistance group Service for Poland’s Victory.44 She made her apartment at No. 6, ulica Fałata available to Gen. Michał Tokarzewski,45 one of the commanding officers of Service for Poland’s Victory, who used it as a contact point. She was sworn in by 2nd Lt. Franciszek Niepokólczycki (nom-de-guerre “Teodor”46), and assumed the nom-de-guerre “Doktor.” She asked for an assignment to a post where she would be able to engage in direct combat against the Nazi German occupying forces.

In the spring of 1940, when a base for sabotage and subversionoperations was being organised within ZWZ (the Union of Armed Struggle)47 and commanded by “Teodor” and his Odwet (“Retaliation”) sabotage and subversiongroup, “Doktor” suggested the creation of women’s sabotage and subversion teams. The idea was accepted on consultation and approval by Col. Janusz Albrecht,48 head of the Chief Command of ZWZ. Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski,49 nom-de-guerre “Szyna,” was to train the first 5-person patrolling team of female sappers during meetings in Dr Franio’s apartment and in the private allotment gardens on Mokotów Field.50 The women sappers trained by “Szyna” trained further 5-woman groups.

Years later, Maj. Zbigniew “Szyna” Lewandowski published the following recollection in the Warsaw weekly Stolica (No. 11, 18 March 1979):

I met Dr Zofia Franio in February 1940. On orders from “Teodor” (Maj. Franciszek Niepokólczycki), commanding officer of Odwet, I was to train the first women’s unit to carry out sabotage and subversion operations. Dr Franio was the person who put forward the idea to have women doing this hard and dangerous duty, and she also commanded the first team of five. I was on my way to her apartment at 6, ulica Fałata, where in the autumn of 1939 Gen. Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski, the first commander of the military organisation Service for Poland’s Victory, later transformed into the Union for Armed Struggle and finally into the Home Army, had his contact point; I was not at all convinced that this task entrusted to me was the right thing to do. Of course, I had no misgivings about Polish women’s courage and patriotism, but in my opinion entrusting them with the task of blowing up railway tracks and bridges was beyond their powers. How wrong I was. In the apartment I was welcomed by a charming lady with prematurely greying hair and a youthful figure in a sports outfit. Seeing her careful and wise gaze, I did not dare to voice my misgivings, which dispersed as soon as they were confronted with her determination, energy and military experience, not only in the medical service but also in combat. She had the kind of strength that won people’s respect and trust. I didn’t anticipate at the time that Dr Franio would save my life twice thanks to her medical skills, but I do remember that I left her apartment convinced that she was absolutely reliable. After a few months, the first five women sappers who were to form the women’s patrol teams were an independent ZWZ sabotage unit, later subordinated to the command of Kedyw (the Sabotage and subversion Executive Committee) in the Warsaw District Home Army. For the entire period under German occupation and the Warsaw Uprising51 the team was commanded by Zofia “Doktor” Franio. . . .

Zofia was able to combine her soft heart, innate kindness and caring attitude towards companions-in-arms with her “on-call” medical tasks in every situation, ever mindful of her duties as a vigilant conspirator, soldier and commander, ready for action at any moment. She was involved in all the activities of the women’s sapper teams: in the production of mines, detonators, grenades, and incendiary devices; moreover, she supervised transports of explosives to about 20 ammunition depots to which the teams had access in Warsaw and its vicinity; together with “Szyna” (Lt. Zbigniew Lewandowski), “Chwacki” (Józef Pszenny52) and “Leon” (Leon Tarajkowicz53) she organised a big sabotage operation codenamed “Wieniec”54 [Wreath] and took part in the legendary Operation “Odwet kolejowy”55 [Railway Retaliation]. Lewandowski recalls this combat operation carried out on 16/17 November 1942:

To an outsider’s eyes, “Doktor” could have passed for a person in perfect control of her nerves. You had to know her well to realise how deeply she experienced each dangerous activity of her teams and how happy she was when they returned safe and sound after a successful operation. Therefore, when Operation “Odwet kolejowy” came up for the demolition of the Łuków railway junction, along which German transports passed on their way to the eastern front, “Doktor” volunteered to join the combat engineering patrol led by “Mira” (Kazimiera Olszewska),56 ostensibly to offer her medical services, but on the spot she immediately joined “Jola” [Jolanta Szenfeld] laying mines in the designated section on the Łuków-Dęblin line. Their task was to derail the German train which was due to arrive from Dęblin at around 11 p.m. Meanwhile, around 7 p.m. on the other side of Łuków, two military transports from Terespol went up on my mines. The place turned into hell: fire alarms started wailing in the town, church bells tolled, ambulances ran through the streets transporting wounded soldiers from the burning train carriages, and German military policemen immediately set out in pursuit of the saboteurs. Hidden in the woods between the tracks and the road, “Doktor” and “Jola” were calmly observing the area full of the policemen out hunting for them. Their only concern was that one of the German patrols crossing the railway tracks could have damaged the delicate wires connecting the mines with the electric igniter. After four hours of waiting, they performed their task as thoroughly and as precisely as they had been ordered to do. Later that night they had to retreat, hastily marching twenty km across marshy terrain and ploughed ground. As “Doktor” told me later, she had experienced only one nerve-racking moment during the operation, namely when she got off at the station in Łuków with a heavy suitcase loaded with explosive materials, she saw German military policemen checking all the travellers’ luggage. What was she to do? She put her suitcase on the ground and shoved it along with her foot, walking slowly towards the exit, absorbed in reading a newspaper as if she did not know what was going on around her. It worked! “If it had not been for my grey hair,” she said, “the suitcase would probably have gone.” The suitcase might have been lost—that was her only concern and not the fact that she could have lost her life! That’s what she was like: always calm, self-controlled, ready for anything, ever ready to help anyone in need, anyone in distress ...

The tasks of the female mining patrols in the Warsaw District Kedyw of the Home Army (nine teams; a total of 55 soldiers and command) were diverse and extremely dangerous. Let me cite the book Kedywiacy by Henryk and Ludwik Witkowski (Warszawa: Pax, 1973):

Among those predominantly male units, determined to conduct subversive combat which many a time called for the sacrifice of one’s life, the activities of the women’s combat engineering patrols deserve special mention. The germ of this unit was a patrol of five created by Lt. “Doktor” Franio in the spring of 1940, comprising “Tosia” [Antonina Mijał-Bartoszewska],57 “Mira” [Kazimiera Olszewska],58 “Kazika” (Kazimiera Skoszkiewicz) and “Nina” (Janina Rudomino-Kochanowska),59 apart from its founder. These women were not selected by random chance. All of them were Women’s Military Training60 instructors before the war, thanks to which they a good foundation knowledge of military matters as well as the right mental disposition and were physically fit. Shortly after the first combat engineering patrol was created, they began specialist training during which the officers taught the young trainees of mine-laying all they knew about explosives, incendiary devices and how to demolish all kinds of objects, especially transport facilities . . .. In addition to the special tasks they were carrying out at the time, these combat engineering patrols were involved in the preparations for a general uprising, distributing and hiding explosives in the vicinity of Warsaw near the transport facilities which were to be blown up . . .. It must be said that at the time no division which could be called a combat engineering team consisted of such a large group of well-trained mine-laying experts. It would be no exaggeration to say that the women’s combat engineering patrols were units whose daily duties were difficult and dangerous, duties that actually could have been nightmares for many male sappers, tasks that could have made hands tremble and hearts flutter. Their most important activities included the production of all kinds of explosives and prototypes of mines and incendiary devices for the squads of the Warsaw District Kedyw, and sapper equipment for the Technical Research Bureau,61 a section of the Home Army Headquarters . . ..

It would be hard to list all the tasks and types of activities conducted by the women’s combat engineering patrols under the command of Dr Zofia Franio. Documentary publications dealing with the combat in occupied Warsaw (for instance the book by Tomasz Strzembosz, Akcje zbrojne podziemnej Warszawy 1939-1944, Warszawa: PIW, 1978) contain numerous mentions and information on this subject.

A separate area of Dr Franio’s resistance activity was her concern and assistance for the Jewish community. She hid and helped many Jews whose lives were threatened. She was involved in wide-ranging operations to deliver weapons to the Jewish Ghetto, carried out in 1942 and in the spring of 1943 by the Warsaw District Command of the Home Army. The women’s combat engineering patrols under her command transported weapons, ammunition, explosives and incendiaries from the Kedyw storage facilities to the Ghetto. Thanks to that, members of the Jewish Combat Organisation (ŻOB)62 entrapped in the Ghetto were not defenceless when the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising63 began.

This description of Dr Franio’s conduct and activities under the German occupation of Poland would be incomplete if it stopped at her commanding and sabotage skills. She was first and foremost a medical practitioner, sensitive to human suffering, worries and misfortune. She adhered to the principles of medical ethics proclaimed by Dr Władysław Biegański:64 “Remember that medicine was born of misery, and its godparents were mercy and compassion. Without its philanthropic element, medicine would be just a common, and perhaps a contrmptible craft...” She remembered these words until the last moments of her life. In pre-war Warsaw she had been a well-known figure among the activists and promoters of physical education, sport, tourism, and among the women’s associations in the Federation of Polish Associations of Defenders of Poland,65 and above all in the Women’s Military Training Association and other women’s groups co-operating with it. She had countless patients, those fully confident that they would get kind and effective help as well as those whose need of assistance her keen eyes spotted despite their reluctance to undergo treatment. Her “doctor’s fee” would be words of unlimited gratitude, devotion and friendship from her patients and from those she consoled or those whose needs she met. Indeed, she gave people not only her cheerful and friendly smile and words of comfort, applying her medical skills and experience, but she also literally gave away everything she had, whatever she thought could be useful to someone else: underwear, shoes, clothes, medications, or food. She did not have much in the appalling conditions under German occupation, but she still wanted to share whatever she had with her friends, colleagues and casual acquaintances, not caring about what she would eat the next day or what she would wear on a cold day if, for example, she was left without a warm pullover because she had given her last one away to a little-known young liaison girl. Someone once said that kindness is like an echo: it always comes back to you.

From the very start of the Warsaw Uprising, at “W-hour” on 1 August 1944,66 several of Dr Franio’s engineering patrols were assigned to work with various combat groups. “Doktor” and the rest of her patrols were in the city centre, in the unit shielding the military publishing house67 on ulica Boduena under the command of Cpt. “Jotes.”68 The women sappers from the “Doktor’s” unit took part in the offensive on the main post office building,69 during which “Alina” (Irena Bredel70) was killed, and in the offensive on the Pasta building71 on ulica Zielna (Kazimierz Moczarski72 mentions this operation in his book Rozmowy z katem73). They were also involved in the offensive against the building of the Blue Police74 in Krakowskie Przedmieście; they helped to make the cut across Aleje Jerozolimskie, and took part in many other combat operations.

Throughout the Warsaw Uprising, the women’s combat engineering teams produced Molotov cocktails, mines and grenades. When their own materials ran out, they used the TNT from unexploded German missiles and Goliaths.75

Work to obtain TNT from unexploded misfires and rubbing it to a powder to produce mines and grenades involved a serious risk of fatal poisoning. As soon as we noticed its first symptoms (blue eyelids and nails, headache and nausea), the team had to stop their work immediately, and another group took over. This happened with me as well. I joined “Doktor’s” team working at No. 23, ulica Bracka (the Jabłkowski Brothers’ shop) in late August 1944 to help with the production of grenades and mines using the explosives from captured armaments. I saw Dr Franio constantly assisting her brave sappers. They shared her cheerfulness and belief in the purposefulness of all this carnage; like her too, they sang soldiers’ songs while doing their difficult job; Zofia loved these songs.

The Home Army promoted Dr Franio to the rank of major, and on 11 November 1942 she was awarded the Cross of Valour76 for her bravery in underground combat operations; on 3 May 1944, she received the Gold Cross of Merit with Swords77 for her outstanding organising services, and the Order of Virtuti Militari (Fifth Class)78 for engaging and commanding in combat for the entire period under German occupation, especially during the Warsaw Uprising. This distinction was conferred in her on 2 October 1944,79 already after the commanding officers had issued the surrender order.

After the surrender, Dr Franio decided to stay in the vicinity of Warsaw; she did not want to go into captivity and become a POW,80 so she left Warsaw in a column of anonymous civilians. For a while she stayed in Malichy.81 At the end of January 1945, she returned to Warsaw. Her old apartment had been gutted in a fire and nothing was left of her belongings. She contacted her old friends and started working as a physician in the Holy Spirit Hospital in Konstancin near Warsaw. She also resumed her work for the Polish Red Cross.

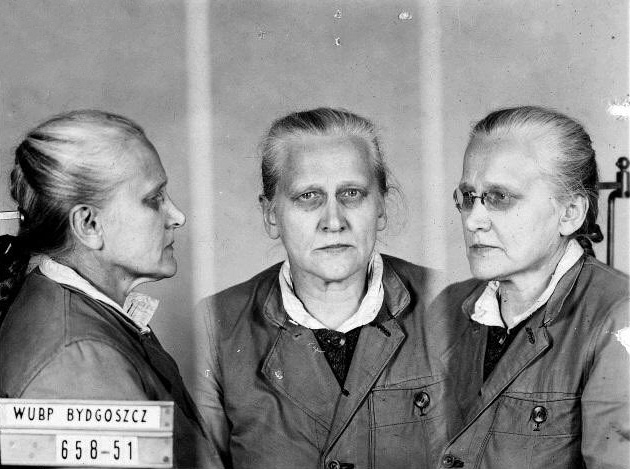

Zofia Franio. Mug shot after arrest by communist Ministry of Public Security. Source: Institute of National Remembrance Archive.

The “winds of fate”—as Kazimierz Koźniewski described the post-war vicissitudes of Kazimierz Moczarski, author of Rozmowy z katem82 in an article published in the magazine Odra, 1973, No. 9)—made her spend 1946-1956 in various places—Warsaw, Fordon, Grudziądz, Inowrocław—where she lived like a recluse. Yet in all those places, her medical experience and social involvement in fighting for human dignity as well as her sensitivity to human misery turned out to be extremely useful.

In 1956-1976, she worked in the public health service in Warsaw: first, in the outpatient clinic on ulica Wiejska, later she was employed as a school physician at a medical secondary school83 at No. 23, ulica Rakowiecka and in a hall of residence at No. 20, ulica Długa for girls attending vocational schools in Warsaw. At this time she tried to provide medical care to her former subordinates, friends and acquaintances. Her compassion and commitment to others was deep and firm. She treated her close and distant friends’ troubles and worries as if they were her own. She trusted people and always believed in them. She never gave in to doubts about the sense of altruism. She considered her profession a mission. Another significant opinion about Dr Zofia Franio, which has not been spoiled by too many superlatives, is the letter of reference issued in June 1973 by the head teacher and school authorities of the Medical Grammar School,84 and seconded by the Basic Party Organization85 and the local branch of the Polish Teachers’ Union:86

[Dr Zofia Franio] has been conscientiously committed to the healthcare of schoolchildren. She often comes to work also outside her official hours to conduct medical examinations and provide care for young people during their internships and during epidemics. She came to work during the flu season, never worrying about her own health. Her attitude to professional duties amazes even the most meticulous teachers. Every year Dr Franio devotes a lot of time and effort to conducting a medical examination of applicants to the school prior to the entrance examination. She performs her duties for the selection of future nursing staff with a lot of enthusiasm and a deep sense of responsibility. She makes an active contribution to school council meetings. The school parents’ committee and parents themselves have a very good opinion of Dr Franio’s attitude towards young people, and have often expressed their gratitude for her involvement and awarded her with cash prizes. The head teacher and school authority holds Citizen87 Zofia Franio in esteem for her long-standing commitment as a school physician who is liked by our pupils and admired by our teaching staff.

She continued to be intensively involved in the Polish Red Cross. In April 1964, following the motion of the Board of Management of the Polish Red Cross, she was awarded its Third Class Badge of Honour88 (No. 17715). In 1971, on the occasion of the golden jubilee of her work for young people, she received a certificate “for many years of active social work in the Polish Red Cross, and in particular for many years of humanitarian service.”

In 1978, the Israeli institution Yad Vashem awarded her its gold medal bearing her name and the title “Righteous Among the Nations.” This was an even more gratifying distinction, because it was completely unexpected. Everyone who knew her can say that everything she did came from the depths of her heart, in line with her philosophy of life, with no thought whether someone would notice it. Her kindness and generosity were extraordinary.

I cannot fail to mention Dr Franio’s great love of the Tatra Mountains. She used to spend all her post-war holidays there; before the war she often visited the PWK centre89 at Istebna on the Vistula). She was happy when she had company to climb Świnica, Orla Perć, Czerwone Wierchy90 or go trekking along some of the unmarked paths of the Western Tatras. When she could not find anyone willing to go climbing with her (her much younger friends complained they would get “short of breath,” wouldn’t have the strength for it, or made other excuses), she would go hiking on her own. In August 1975, while descending from Świnica (at the age of 76) in very bad weather conditions, she had an accident. Members of GOPR (the Polish Volunteer Mountain Rescued Service) carried the stubborn mountaineer down. She had a dislocated leg and general injuries. Naturally, she thanked GOPR in writing for their dedication, care and kindness. When she recovered, she was rearing to climb the same mountain again and tackle other Tatra paths. She made friends with Bronka Staszel-Polankówna of Krzeptówki, a former Polish skiing champion, and used to stay at Krzeptówki.

The last two years of her life were challenging for her: a test of fortitude, endurance and internal strength to live with a serious disease. For a long time, her relations with her relatives were difficult due to her hearing problem. She could not get used to wearing a hearing aid. But she always kept smiling. She loved music, and continued to attend concerts, just as she had done in the old days; and she found the time to attend meetings and events organised by the Maria Konopnicka Society.91 Although her friends asked her to look after herself and stop working as a part-time physician in the girls’ boarding school, she did not want to hear of it, saying “Trees die standing tall.”92 The illness got the better of her; she had an operation, but it did not bring her any relief. In 1978, she celebrated her birthday and name-day93 as usual, receiving visits from crowds of friends and colleagues at home. As always, there was a splendid party, but the hostess’s face was changed and her eyes were dim although all the time her face was still lit up with a kind smile. She distracted our attention from asking about her condition by showing concern for other people’s troubles and health problems; she also asked us to sing soldier’s songs; in a word, she disarmed our vigilant thoughts and worries for her health.

She died on 25 November 1978. Crowds of her relatives, friends, fellow soldiers and co-workers, old and young, paid the last respects at her funeral in the Warsaw Powązki cemetery. We all knew that a good, generous and noble person had passed away. As we stood at her graveside and listened to the obituaries full of grief, given by her comrades in arms and by Maj. “Szyna” Lewandowski who had introduced “Doktor” and her subordinates to the secrets of combat engineering work 38 years earlier, and by Dr Tomasz Strzembosz, the historian of the underground resistance operations in Warsaw, we pondered on her life’s work. Her opus magnum was somewhat strange: she had attended a school for young ladies and had been awarded a diamond ring from the Tsar of Russia; later she was a nurse in field hospitals, a physician in Warsaw hospitals and outpatient clinics for the poor, a sabotage and subversion officer, a caring Samaritan woman and a sapper blowing up railway tracks leading to the eastern front; the most faithful friend of those in need regardless of their race, religion or origin, a thoughtful educator of the young, a modest, meek person who was sparing in her speech and in showing affection, always a loyal companion for better or worse.

Anyone who had the chance to meet Dr Franio thought and spoke of her with the greatest respect. We bade farewell to a woman who belonged to a bygone generation of Polish physicians marked by such strength of character, representing the truest moral values, and characterised by their professional ethos, attitude and conduct.

***

This article about Dr Zofia Franio is based on the following sources:

- Dr Franio’s personal biographical notes and curriculum vitae;

- Her personal documents, some now owned by her nieces and some in the collections of the Commission on the History of Women in the Struggle for Polish Independence, in the Warsaw Society of the Friends of History;94

- Publications

- Tomasz Strzembosz, Akcje zbrojne podziemnej Warszawy 1939-1944, Warszawa: PIW, 1978;

- Henryk Witkowski and Ludwik Witkowski, Kedywiacy, Warszawa: Pax, 1973;

- Adam Borkiewicz, Powstanie Warszawskie, Warszawa: Pax, 1964;

- Władysław Bartoszewski, 1859 dni Warszawy, Kraków: Znak, 1974;

- short mentions of Dr Franio in other books and periodicals.

- Information provided by her closest collaborators, including “Tosia” (Dr Antonina Mijal-Bartoszewska) and “Mira” (Kazimiera Olszewska);

- 1929-1939 issues of the PKW monthly Dla Przyszłości;

- My own recollections of meetings with Dr Franio in 1935-1978.

***

Translated from original article: Zastocka, W., “Dr Zofia Franio.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1980.

Notes

- A citation from Adam Mickiewicz, Pan Tadeusz or The Last Foray In Lithuania, Book XI, v. 78; translated from the Polish by George Rapall Noyes, 1917, London And Toronto, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. Paris: J. M. Dent Et Fils New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. The reference is a poetic way of reminding readers that Poland’s independence was only restored in 1918, after 123 years of dismemberment on being partitioned between Austria, Russia, and Prussia in the late 18th century.a

- A line from the Polish Riflemen’s Association’s anthem “Naprzód drużyno strzelecka” (Forward the rifle squad). The Riflemen’s Association (Związek Strzelecki) was founded before World War I and fought for Polish independence.a

- Many times during the 123 years of Poland’s non-existence as an independent state, Polish people rose up against the Partitioning Powers.b

- Institutes for Noble Maidens were a type of ladies’ college in late Imperial Russia. They were founded by Ivan Betskoy. The first and most famous of these colleges was the Smolny Institute of Noble Maidens in St. Petersburg. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institute_for_Noble_Maidens.a

- She studied at the Medical Institute for Women, founded in 1897 as the first institution in Europe that provided an opportunity for women to acquire an education in medicine at the tertiary level.c

- On the Eastern front during the First World War, in which Ruissia and Prussia were belligerents on opposite sides.b

- In the summer of 1915, when the German army crossed the frontline and were advancing into Russian territory, the Russian military forced the inhabitants of its western provinces to evacuate east. To make the people leave, the military spread rumours that the Germans would rob them, rape their women and kill the men. About two to three million were evacuated, the vast majority of them were Belarusians and Ruthenians.c

- The Society of Friends of Polish History and Literature (Polskie Towarzystwo Miłośników Historii i Literatury) in Saint Peterburg was a learned society active in 1916–1920. Its aim was to promote Polish scholarship, history and literature. See www.polskipetersburg.pl.c

- The Psychoneurological Institute was founded in 1907, and transformed in 1920 into the Second Leningrad Medical Institute.c

- The shot fired from the Aurora at the Tsar’s Winter Palace in St. Petersburg is generally regarded as the incident triggering the October (Russian) Revolution of 1917.b

- At the end of World War 1 in 1918, Poland was restored as an independent, sovereign state at the Paris Peace Conference. Polish independence was No. 13 on President Wilson’s list of Thirteen Points. However, the Peace Conference did not establish all of the new country’s frontiers, and fighting with neighbouring states broke out along several of the Polish borders. Here the war implied but not named directly is the combat along Poland’s eastern border, culminating in the Polish–Bolshevik War of 1920, when the Bolshevik Army invaded Poland and nearly reached Warsaw, but was ultimately beaten and forced to retreat in August 1920. This article was written and published under the Polish People’s Republic, when Poland was in the Soviet Bloc, so the subject of the Soviet invasion could not be mentioned for censorship reasons and was merely implied but left unsaid.b

- Sanitary trains and field hospitals were familiar medical units along the fronts of the First World War and (in Poland) during the fighting that occurred at the end of the First World War to secure the new state’s borders. See https://theworldwar.pastperfectonline.com/bysearchterm?keyword=110th+Sanitary+Train.b

- After the Polish—Bolshevik War of 1920.b

- Doctor of General Medicine, the title awarded to students graduating in Medicine from Polish universities at the time.b

- The war meant here is the Polish—Soviet War of 1920. See 11-13.b

- The Social Committee for Women’s Military Training (Komitet Społeczny Przysposobienia Kobiet do Obrony Kraju) was founded in 1922 when two Polish independence organisations, the Riflemen’s Association and the Polish Military Organisation, were amalgamated. Its aim was to train women to serve in auxiliary units. https://fbc.pionier.net.pl/details/nnnlx8w.c

- Koło Polek.b

- Polski Czerwony Krzyż.b

- Polski Bialy Krzyż, a Polish organisation associated with the military, founded in the USA during the First World War to provide aid for war victims.b

- Organizacja Harcerek ZHP.b

- Katolicki Związek Polek.b

- Klub Wioślarek.b

- Koło Mieszczanek.b

- Oddział Żeński Sokoła. Sokół was Polish gymnastic association founded before the First World War. It promoted the patriotic and pro-independence attitude.b

- Związek Kobiet Pracujących w Handlu i Biurowości.b

- Związek Młodziezy Wiejskiej.b

- Związek Strzelecki, a paramilitary organisation which fought for Polish independence during the First World War.b

- The Women’s Military Training Organisation (*Przysposobienie Wojskowe Kobiet—PWK) was a women’s paramilitary organization formed in 1923 on the initiative of veterans of the Riflemen’s Association and Polish Military Organization. PWK had over 47 thousand members when the war broke out.c

- Witold Eugeniusz Orłowski (1874–1966), physician specialising in internal medicine. Professor and head of the Second Internal Medicine Clinic of the University of Warsaw, and creator of its pathophysiology and biochemistry units.c

- Ustawa z dnia 9 kwietnia 1938 r. o powszechnym obowiązku wojskowym (Dziennik Ustaw 1938, No.25, Item 220). Online at http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19380250220/O/D19380220.pdf.b

- Ministerstwo Spraw Wojskowych.b

- The National Office for Physical Education and Military Training (Państwowy Urząd Wychowania Fizycznego i Przysposobienia Wojskowego) was founded in 1927 following the initiative of Józef Piłsudski. The institution coordinated the activities of offices and social organisations for the promotion of physical education and military training.c

- Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych.b

- Janusz Głuchowski (1888–1964) was a divisional general of the Polish Army.c

- From 1933 to 1989 Polish associations regarded as particularly important for the national or social interest were given the status of high utility associations. See https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stowarzyszenie_wyższej_użyteczności.b

- Following the German invasion of Poland and the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939, important national institutions were evacuated east. Trawniki is a small place about 215 km south-east of Warsaw; the city of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine, but on Polish territory in 1939) is 395 km to the south-east of Warsaw. Military units, conscripts, and volunteers were also ordered to head east, but mass evacuation stopped when the Soviet Union invaded Poland, crossing its eastern border on 17 September. This information is not given in the article, which was written and published when Poland was in the Soviet Bloc and any mention of such matters would have been censored.b

- Halina Wasilewska, nom-de-guerre “Krystyna” (1899-1961), served in the medical corps of the First Polish Legion during World War I. In 1918 she was a courier; dressed as a man, she took part in the defence of Lwów as a communications officer for the Legions. After hostilities ended she was one of the regional PWK organisers. In 1928-1934 she was commander of the Lwów PWK division and manager of the Polish forces physical training unit for Lwów. In 1939 she was the commanding officer of the PWK Instructor Training Centre in Warsaw. In September 1939 she was the commander of the Women’s Battalion of auxiliary forces for the Lwów National Defence Brigade. She took an active part in the defence of Lwów until its capitulation. She was arrested in 1943 and imprisoned in the Pawiak jail (Warsaw). On 3 April 1944, she was sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp. After its liberation she stayed in Western Europe, was promoted to the rank of major and assumed command of the 2nd Battalion of the Women’s Army Service in Meppen with the 1st Armoured Division under the command of General Stanisław Maczek. See https://1wrzesnia39.pl/39p/biogramy/8817,Halina-Wasilewska.html.c

- Wanda Wasilewska (1905–1964), was a Polish and Soviet novelist and journalist and a left-wing political activist who became a devoted communist. Wasilewska was a trusted advisor to Joseph Stalin and her influence was essential to the establishment of the Polish Committee of National Liberation in July 1944, and thus to the formation of the Polish People’s Republic. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wanda_Wasilewska.a

- Until the war the city of Wilno was in the north-eastern corner of the Republic of Poland. It is now known as Vilnius and is the capital of Lithuania.b

- See comment 36.b

- The original Polish text passes over the information that Lwów surrendered to the Soviet aggressor—see other comments.b

- Typhoid is a bacterial disease and can be fatal. The source of infection is usually dirty water or waste contaminated with Salmonella. The symptoms of typhoid are fever, abdominal pain, delirium, extreme exhaustion and a pink rash.c

- Maria Wittek, nom-de-guerre “Mira,” (1899-1997), Brigadier General of the Polish Army. In 1917 she joined the Polish Military Organization and was a student in the Faculty of Mathematics of the University of Kiev. In December 1919 she joined the Polish Army. In 1920 she served in the Women’s Volunteer Legion in the defence of Lwów. In 1921 she was posted to the Women's Volunteer Legion, later she was head of the Training Department of the Social Committee for Women’s National Defence Training. In 1928–1934 she was commander-in-chief of PWK, and from 1935 head of the Department of Women’s Physical Education and Military Training at the National Office of Physical Education and Military Training. During Poland’s defence against German aggression in 1939 she was commander-in-chief of the Women’s Battalions of the Auxiliary Military Service. From October 1939 to January 1945 she commanded the Women’s Military Service in the Main Headquarters of the Union of Armed Struggle—Home Army. On 2 May 1991 President Lech Wałęsa promoted her to the rank of brigadier general. She was the first woman in the history of the Polish Army to hold this rank. Source: Słownik biograficzny kobiet odznaczonych Orderem Wojennym Virtuti Militari, Elżbieta Zawacka et al. (eds.), Toruń: Fundacja „Archiwum i Muzeum Pomorskie Armii Krajowej oraz Wojskowej Służby Polek,” 2004.c

- Service for Poland’s Victory or Polish Victory Service (abbreviated SZP) was a Polish resistance movement in World War II, created on orders from General Juliusz Rómmel on 27 September 1939. The commander of SZP was General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski. This underground organisation was tasked with continuing armed combat to liberate Poland in the pre-war borders of the Second Polish Republic, the restoration and reorganization of the Polish army and the establishment of a Polish Underground State subject to the authority of the Polish Government-in-Exile. On 13 November 1939, on orders from the Commander-in-Chief, Gen. Władysław Sikorski, it was disbanded and succeeded by the Union of Armed Struggle (ZWZ, Związek Walki Zbrojnej), which was in turn succeeded by the Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK), the largest underground resistance movement in occupied Europe.c

- Michał Tokarzewski-Karaszewicz (1893–1964) general of the Polish Military Organization. Fought in the Battle on the Bzura against the invading German army in 1939. Arrested in March 1940 by the NKWD and sent to a labour camp near Vorkuta. Liberated following Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union and appointed second-in-command of the Polish Army in the East (the Polish Second Corps under the command of Gen. Anders). After the War stayed in exile in England. Source: Piotr Stawecki, Słownik biograficzny generałów Wojska Polskiego 1918-1939, Warszawa: Bellona, 1994.c

- Franciszek Niepokólczycki, nom-de-guerre “Teodor” (1900–1974), lieutenant colonel in the Polish Army under the Second Polish Republic. In April 1940 appointed commander of a ZWZ special “Reprisal” unit charged with sabotage and armed combat; ZWZ and later AK officer, combatant in the post-war anti-communist underground movement, incl. the Freedom and Independence Association (Wolność i Niezawisłość, WiN). Arrested by the Communists and sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment. Liberated in the thaw of 1956 following the death of Stalin. Source: Andrzej K. Kunert, Słownik biograficzny konspiracji warszawskiej 1939-1945, Warszawa: Pax, 1987, vol. 2.c

- Związek Walki Zbrojnej (ZWZ), a Polish underground resistance group operating in the early period of the war, the predecessor of the AK (Armia Krajowa) Home Army.b.

- Janusz Albrecht (1892–1941) Polish Army colonel; Deputy Commander of ZWZ and Chief of Staff of its headquarters. Arrested by the Gestapo, broke down under torture and passed information. Committed suicide by taking cyanide. Source: Andrzej K. Kunert, Słownik biograficzny konspiracji warszawskiej 1939-1945, Warszawa: Pax 1987, vol. 1.c

- Zbigniew Lewandowski, nom-de-guerre “Szyna” (1909-1990) deputy commander of sappers in the Warsaw District, commanding sapper railway units. He also organized weapons to aid the Jewish Combat Organization operating in the Warsaw Ghetto. See www.1944.pl.c

- Mokotów Field, Pole Mokotowskie—a large municipal park in the centre of Warsaw. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mokotów_Field.b

- The Warsaw Uprising of the summer of 1944, not to be confused with the Ghetto Uprising of April 1943.b

- Józef Pszenny nom-de-guerre “Chwacki” (1910-1993) commander of the Sappers Batalion of the Warsaw-Praga Division, a ZWZ unit. Participated in the “Wieniec” operation. See www.1944.pl.c

- Leon Tarajkowicz, nom-de-guerre “Leon” (b. 1911) commander of the sabotage unit of Division VII “Obroża” in the “Radosław” Group during the Warsaw Uprising. See www.1944.pl.c

- Operation “Wieniec” was carried out on the night of 7/8 October 1942 as the Home Army’s first sabotage operation to destroy German railway communications. It resulted in blocking the Warsaw railway junction. The Germans responded by shooting 39 prisoners held in Pawiak jail and hanging another 50. See www.dzieje.pl.c

- Operation “Odwet kolejowy” was a response to the executions the Germans carried out after Operation “Wieniec.” The Home Army blocked railway lines leading east across the Vistula River. Five trains and a railway bridge were blown up, other bridges were damaged and rail traffic was paralysed. See www.dzieje.pl.c

- Kazimiera Olszewska, nom-de-guerre “Mira” (1912–1985), served in the Association of Retaliation from 1939. A member of the first mining patrol. Fought in the Warsaw Uprising in the district of Ochota and later in Powiśle Czerniakowskie. After the war she joined the WiN anti-communist resistance movement; she was arrested, and sentenced to eight years in prison. Released and rehabilitated in the 1956 thaw after the death of Stalin. See www.1944.pl.c

- Antonina Mijal, nom-de-guerre “Tosia” (1915-1986) was the deputy head of the female mining patrols. She took part in combat operations carried out by the Home Army. In 1942–1944, she attended the the Private Vocational. School for Auxiliary Sanitary Personnel of Doctor Jan Zaorski. She produced grenades and mines during the Warsaw Uprising. See www.1944.pl.c

- Kazimiera Skoszkiewicz nom-de-guerre “Kazika” (1914–1982) a member of the first women’s mining patrol organized in 1940 by Zofia Franio. See www.1944.pl.

- Janina Rudomino nom-de-guerre “Nina” (1908–1987), a member of the first women’s mining patrol. In the Warsaw Uprising she produced grenades under the supervision of Captain Witold Kwiatkowski nom-de-guerre “Antek” on ulica Mokotowska. Source: Archiwum i Muzeum Pomorskie Armii Krajowej i Wojskowej Służby Polski (online access).c

- See Comment 28.

- Biuro Badań Technicznych przy Komendzie Głównej AK.c

- The Jewish Combat Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa—ŻOB) was a Polish Jews’ resistance movement. It was created in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942. Its first commander was Mordechaj Anielewicz. Units of ŻOB were also formed in Kraków, Częstochowa, Będzin, and Sosnowiec.c

- The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising broke out in April 1943, in response to the German decision to “liquidate” (i.e., destroy) the Ghetto and send the rest of its inmates to death camps. Its last inhabitants decided to die fighting. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warsaw_Ghetto_Uprising.b

- Władysław Biegański (1857–1917) was a Polish specialist in internal medicine. He was also interested in the philosophy of medicine, the logic of medicine and psychology.c

- Unia Polskich Związków Obrończyń Ojczyzny was part of the international FIDAC (Fédération Interalliée Des Anciens Combattants) founded in 1925. It conducted charity and editorial activities.c

- The Warsaw Uprising was scheduled to (and did) start at “W-hour,” 17.00 hours on 1 August 1944.b

- Tajne Wojskowe Zakłady Wydawnicze (Secret Military Publishing House) was the secret printing and publishing house of the Polish Underground State. It was created in Warsaw in late 1940 and managed by Jerzy Rutkowski of the Polish resistance movement’s Bureau of Information and Propaganda. The house was probably the largest underground publisher in the world. During the Warsaw Uprising in the late summer of 1944, its operations in Warsaw went public as Wojskowe Zakłady Wydawnicze (Military Publishing House). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tajne_Wojskowe_Zakłady_Wydawnicze.a

- Jerzy Skupieński, nom-de-guerre “Jotes” (1913-1987), commander of the Home Army sappers for the Warsaw District.c

- After several attempts, on 2 August in the afternoon AK men managed to take the main post office building, which had been defended by a large German unit. The insurgents held the post office building until the end of the Uprising. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zdobycie_Poczty_Głównej.b

- Irena Bredel, nom-de-guerre “Alina” (1917-1944), commander of a mining patrol in the Warsaw Uprising. www.1944.pl.c

- PAST (Polska Akcyjna Spółka Telefoniczna), also known as PASTA), was a Polish telephone company in the period between the world wars. Its headquarters were located in a tall building, a landmark on the Warsaw skyline. During the Uprising there was heavy fighting for the PASTA building, lasting fromn 2 to 20 August, when it was eventually taken by the insurgents and held until the end of the Uprising. See https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/PAST.c

- Kazimierz Moczarski, nom-de-guerre “Rafał” (1907–1975), journalist, writer and officer of the Home Army. Worked during the war in the Bureau of Intelligence and Propaganda (BiP) for the AK’s Warsaw District. Directed one of the insurgents’ radio stations. Arrested in 1945 by the Communists sentenced first to 10 years in prison, later commuted to a death sentence. Held in the notorious Mokotów jail, in the same cell as SS-Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop, who was responsible for the annihilation of the Warsaw Ghetto. Source: Andrzej K. Kunert, Słownik biograficzny konspiracji warszawskiej 1939-1945, Warszawa: Pax 1987, vol. 1.c

- Moczarski made a record of his “conversations with an executioner,” conducted with Nazi war criminal Jürgen Stroop, who was his cell mate in the Communist secret police prison. The book was later published. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kazimierz_Moczarski. Jürgen Stroop (1895-1952), Nazi German war criminal responsible for the annihilation of the Warsaw Ghetto after the 1943 uprising. His crimes resulted in the death of over 50,000 people. A committed Nazi, arrogant and unremitting until the very end, he was put on trial on 18 July 1951 for the war crimes he committed in Poland and executed by hanging in the Mokotów Prison on 6 March 1952.c

- The Blue Police (Granatowa policja), the police during the Second World War in the Generalgouvernement (German-occupied Poland). Its official German name was Polnische Polizei im Generalgouvernement (Polish Police of the General Government). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Police.c

- The Goliath tracked mine (German: Leichter Ladungsträger Goliath—Goliath Light Charge Carrier, the “beetle tank”) was a series of two unmanned ground vehicles used by the German Army. Goliaths carried up to 100 kg of high explosives.c

- Krzyż Walecznych.b

- Złoty Krzyż Zasługi z Mieczami.b

- Order Virtuti Military (Klasa V), the highest Polish military distinction awarded for bravery to an individual.b

- The date of the capitulation is generally taken as 2 October; however, we know that the surrender negotiations continued into 3 October, the day on which the ceasefire was officially signed. See https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Powstanie_warszawskie.b

- After the surrender, the Germans took the insurgents into captivity and sent them to POW camps in Germany. They forced the civilians to leave the city, which they razed to the ground. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warsaw_Uprising.b

- Malichy is a small place about 17 km (10.6 miles) south-west of Warsaw.b

- See Comment 73. The article implies that during the Stalinist period in People’s Poland (1945-1956), Dr Franio had to lead “the life of a recluse,” because, like many other veterans of the Warsaw Uprising, she could have faced reprisals such as imprisonment, a death sentence, or deportation to the Soviet Union. After 1956 the Communist regime relaxed, but reprisals still continued to affect some veterans of the Uprising.b

- Liceum Medyczne nr 4 im. T. Chałubińskiego.b

- Liceum Medyczne.b

- The school branch of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR, the ruling Communist Party). In Soviet Bloc countries all institutions such as schools, factories, offices, etc., had to have an in-house PZPR branch, which interfered in the running of the institution.b

- Związek Nauczycielstwa Polskiego, a Communist-controlled teachers’ union.b

- The title obywatel (citizen) was used by Communist Party members to address all citizens, and in general it was the officially accepted form of address under the Polish People’s Republic.a

- Odznaka Honorowa PCK III stopnia.b

- Istebna is a village in the Silesian Beskid Mountains. The centre was built in 1927 with funds from the annual contributions of PWK members. In the interwar period PWK camps were organised there.c

- Świnica (2,301 m) is a peak in the High Tatras on the Polish-Slovak border; Orla Perć is a 4.3 km–long high-altitude ramblers’ route in the Polish High Tatras; and Czerwone Wierchy is a group of 4 peaks in the Zakopane area with a high-altitude ramblers’ route of 15.2 km running along them, the highest point along it is 2,122 m above sea level.b

- Towarzystwo im. Marii Konopnickiej was registered in Warsaw in 1960. Its main purpose was the promotion of Konopnicka’s literary work and “her way of life” as a patriot and outstanding social and humanist activist. Maria Konopnicka (1842-1910) was not only a Polish poet, novelist, children’s writer, translator, but also an editor, journalist, a campaigner for women’s rights and for Polish independence. See the source.a

- The title of a play by the Spanish dramatist Alejandro Casona (1903–1965). Original title: Los Árboles mueren de pie. See https://www.alejandro-casona.com/english.htm.b

- Traditionally in Poland people celebrate their name-day, i.e., their patron saint’s feast day, which for Zofia would have been 15 May.b

- Towarzystwo Miłośników Historii w Warszawie. b.

a—notes by Maria Kantor, the translator of the text; b—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; c—notes by Anna Marek, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.