Author

Małgorzata Dominik, MD, 1941–1979, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy (now Jagiellonian University Medical College).

We often commemorate the heroes of the last War, especially when we want to pay tribute to those who showed their complete dedication and laid down their lives. We remember Janusz Korczak,1 who volunteered to accompany the Warsaw Ghetto orphans in his custody and went with them to the death camp, as well as Maksymilian Kolbe,2 another volunteer who gave up his life in Auschwitz to save a fellow prisoner from punishment of death by starvation. However, so far the general public has not heard the story of Dr Halina Jankowska, who died with her patients under the rubble of the Hospital of St. John of God in Warsaw,3 although the wartime history of the establishment as such has been studied fairly extensively (Falkowski). Dr Jankowska deserves to be more widely known, especially as her life and work is an important contribution to the recent history of Polish psychiatry, for instance its condition under the German occupation of Poland.

Before the War, Dr Halina Jankowska was a recognized figure in Polish medical circles. She was born on 24 September 1890 in Berdyczów, in the region of Volhynia.4 Her father was a railway engineer and her mother was an educationalist. Dr Jankowska received her secondary education in a private school run by Jadwiga Sikorska in Warsaw.5 She completed her medical studies in 1918 at the Women’s Medical Institute in St. Petersburg.6 After returning to Poland, she had her graduation certificate nostrificated by the University of Warsaw. She started work as a doctor in Winnica7 in the south-eastern region of Podolia and soon started a specialisation in psychiatry. At the end of 1919 she started work in Tworki mental hospital,8 under Prof. Witold Łuniewski’s9 headship; later she was employed in Warsaw’s Hospital of St. John, and from 1923 in Wilno.10

In Wilno she was appointed Senior Assistant to Prof. Antoni Mikulski11 in the Chair of Psychiatry at the Stephen Báthory University. The Psychiatric Clinic shared premises with the Military Hospital’s Neurology and Psychiatry Ward, but the facilities were far from the clinical standard. Prof. Mikulski died in April 1925 and for the next two years the Chair was vacant. It was only after Dr Rafał Radziwiłłowicz12 had been appointed to the professorship that the Chair of Psychiatry was offered better premises and in 1927 a conversion scheme started to improve its research and teaching potential. During her time in Wilno, Dr Jankowska focused entirely on psychiatry. Dr Anna Kulikowska has given an account of that period in Dr Jankowska’s life as well as the reasons why she left the city:

Dr Jankowska put a lot of effort into organising the Wilno institution. She ran the clinic, prepared for her lectures, and also had practical classes with students. In 1929 Prof. Radziwiłłowicz died suddenly and the Chair of Psychiatry was vacant again for a long time. Dr Jankowska continued to manage the clinic, teach students, and carry out her own research. But the continually makeshift arrangements were a source of many problems for her, especially as she wanted to cope with the situation as well as she could, though she was still a young and relatively inexperienced doctor. In 1931 the Chair of Psychiatry acquired a new head, Prof. Maksymilian Rose. . . .13 Soon after his arrival, Dr Jankowska left the clinic and started organising home care for the mentally ill and convalescents. At the time, outpatient care for mental patients was an urgent problem. . . . As there were far too few hospital beds for the mentally ill in the region of Wilno, grass-roots initiatives started in very many places to set up some form of care, though unsupervised by a doctor or competent nursing staff. Therefore sometimes the patients were abused or cheated.

Dr Michał Marzyński14 wrote in his diary:

Dr Podwiński and Dr Wirubski discovered that in Dokszana15 and other villages in the area family care had been provided for the mentally ill for several decades. The doctors tried to make it as humane and well-organised as possible. Upon his arrival in Wilno, Prof. Rose showed an interest in the problem. As he was an authority in his discipline and had good connections, he managed to elucidate the legal status of this unique mental health care system, especially as it was practically the only one of its kind that was operational in Poland. I don’t know who suggested that Dr Jankowska should be in charge of the mentally ill in the villages, but she became very enthusiastic about the project. She spared no effort and showed a lot of ingenuity and dedication. On a few occasions, I joined her on her rounds. She visited her patients in all kinds of weather, wet and rainy or frosty in the winter, indefatigably traversing the countryside in horse-drawn carts or sleighs. Finally, a basic system of home care was arranged and could be handed over to her successors.

Kulikowska, and Bilikiewicz and Gallus provide the following information:

With her unflagging energy, Dr Jankowska wanted to replace this poor-quality care with appropriate mental health services. The project required not only a lot of work, but also courage, because the authorities in the region were reluctant to help. Yet, thanks to her selfless, uncompromising yet tactful attitude, she managed to establish a well-functioning system that cared for the mental health of about 800 patients. In recognition of that achievement and her outstanding work in the field of psychiatry and social welfare, she was awarded the Order of the Tenth Anniversary of the Restoration of Independence.16 The catchment area was extremely large, and so visits took up all of her time. So, although she found the result of her work fine and satisfying, she was unable to pursue her research interests. She started looking for a place where she would be able to pursue her scientific work. At that time the position of a ward physician at St. John’s Hospital fell vacant and Dr Jankowska decided to apply. She was the successful candidate, . . . and [in 1935] became ward physician of the Women’s Ward No. 2 and held that post until her death.

More details concerning the circumstances of Dr Jankowska’s resignation in Wilno are offered by Dr Marzyński:

During the “interregnum” in the clinic, that is from the death of Prof. Radziwiłłowicz to the arrival of Prof. Rose, Dr Tokałło was the adjunct professor and nominal head, but Dr Jankowska was the actual ward physician. Her relations with the new head, Prof. Rose, were good initially, but deteriorated shortly afterwards. Their views on psychiatry and outlooks on life as well as their individual experience were divergent, so conflicts kept arising, because Dr Jankowska was unwilling to reconcile herself to Prof. Rose’s authority, while he either could not or would not acknowledge and make use of her immense skills, acquaint her with his working methods, or persuade her to follow them, although he knew they were so very different from the mindset and manner she had adopted in Prof. Radziwiłłowicz’s times (Marzyński).

At that time being appointed a ward physician was a splendid achievement for a fairly young woman doctor and a milestone in her career. Before the War, it also secured professional independence, a good social status, and a handsome salary. Consistent in her academic pursuits, Dr Jankowska started working for a mental health clinic housed in the same building as St. John’s Hospital on ulica Konwiktorska (Filar; Jaroszewski; Szumigaj; and Kulikowska). But even earlier, when she was working in Wilno, she had received several scholarships and travel grants to visit mental health institutions in Germany, France, and Great Britain. She used every opportunity to continue her professional development. She published the results of her research and medical observations in Polish medical journals (Rocznik Psychiatryczny, Polska Gazeta Lekarska, Warszawskie Czasopismo Lekarskie, and Pamiętnik Wileńskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego). An incomplete and inaccurate bibliography of Jankowska’s papers was published by Stanisław Łoza. Most of her papers were on psychopathology, with subjects like “A case of delusional psychosis in the course of post-encephalitic Parkinsonism,” “A case of paraphrenia following Kretschmer’s sensitive delusions of reference,” “A case of alcoholic hallucinosis,” “On depersonalisation in hallucinations,” and “On the biology of emotions.” She was also interested in neurology, with papers on “A case of Wernicke’s aphasia following left hemiplegia,” “Fits of negativistic stupor in the course of taboparesis,” and “Some remarks on hereditary torsion dystonia.” Dr Jankowska’s other studies focused on the psychology of children (e.g., “Intelligence levels among primary school pupils in the city of Wilno”), social medicine (“Family care for the mentally ill in the Wilno region”17), and various interdisciplinary problems (“Liver tests in epilepsy”). All her papers have a solid research foundation and are well documented (she describes many cases, gives a broad bibliography, and her statistical data is meticulously presented). Also, they refer to a variety of experiments and tests (e.g., experiments on animals and thorough biochemical tests), so they still have a value today, after several decades. Obviously it is outside the scope of this biographical sketch to discuss Dr Jankowska’s scientific publications in detail. According to Zdzisław Jaroszewski, the person best qualified to assess her achievement is Prof. Mieczysław Kaczyński, head of the Clinic of Psychiatry at Lublin Medical Academy.

Dr Jankowska pursued other academic interests, not limited to her clinical work in mental health centres. From 1935, by which time she was an experienced psychiatrist, she gave lectures at the Institute of Special Education18 in Warsaw on child psychopathology. Prof. Maria Grzegorzewska,19 the founder of the Institute and today its head,20 described Dr Jankowska in the following way:

She was so dedicated to her job, so engaged in her research interests, so responsible and utterly devoted to her patients that she had practically no time left for a social life, which is why we knew her only from work. As soon as she finished her lecture in the Institute, she hurried to the hospital. Sometimes she stayed for a minute longer to explain something to her listeners or to help somebody understand a difficult topic. Her personal contribution to the atmosphere of the Institute was her spiritual strength, calmness, and order. Her moral fortitude, perseverance, resoluteness, civil courage, and truthfulness were present in the look in her eyes and in the deep, serious, and kind tone of her voice. One could sense her inner harmony in relation to the most important things: a self-aware life, the choice of one’s path, and the attitude towards other people. When she entered the hospital ward, her patients, who were mentally ill people, went up to her as if they were coming out into the sun. . . . They trusted her and she never let them down.

Dr Jankowska’s colleagues had a very good opinion of her, as well. Dr Franciszek Szumigaj,21 who worked in her ward until the 1944 Warsaw Uprising,22 remembered her as a gifted professional and a good organiser and leader, tolerant towards her staff and kindly towards her patients. In her opinion, it was the patients who were the most important. She did not even spare her own free time to see them. Dr Jankowska was a popular and immediately recognizable figure. She was tall, sharp-featured and had a profound look in her eyes. She was composed, resolute, energetic, “strong-minded and principled,” according to her colleagues at work. At the same time, she was friendly and charming and had a strong influence on her milieu. People found her very feminine, delicate, and tending to romanticise. All who knew her say that what with her personality and lifestyle, she seemed to be striving for the heroic (Szumigaj).

Dr Jankowska worked very hard for the common good. During her university years, she joined a students’ society called Odrodzenie23 and the women students’ association Spójnia.24 As I have said above, she was a pioneer of home care for the mentally ill in the region of Wilno and she also initiated and carried out research on the development of primary school children. She continued similar activities when she moved to Warsaw. She was noticed by some of the top Polish writers. This is how Jerzy Zawieyski25 portrayed her:

Once, when I was spending time in the company of Mrs W. N., I briefly met a person whom I shall never forget. It was Dr Jankowska, a psychiatrist and ward head of St. John’s Hospital in Warsaw, paying a fleeting visit. A beautiful and fairly young woman. Later I learned that during the War, under German occupation, the Germans deported the mentally ill26 to get rid of this human “burden” and killed them with poison gas. Dr Jankowska did not desert her patients and, like Korczak, died with her wards, although she could have saved herself. She did not practise a religion and was not a member of any church.

When Poland was invaded by Germany in 1939, Dr Jankowska was working in St. John’s Hospital in Warsaw. Dr Zdzisław Jaroszewski27 describes that period of her life:

When the War broke out, Dr Halina Jankowska . . . rose to the challenge and showed supreme courage, composure, calm, and willpower. During the defence of Warsaw in 1939, St. John’s Hospital took in a large number of wounded, even though it had its own inpatients. For those suffering and dying people, Dr Halina Jankowska was a benevolent, gentle spirit who alleviated their pain and brought them comfort. During the dark night under German occupation, in the early spring of 1940, this resolute, brave woman joined the resistance movement and started to make medical arrangements for the forthcoming uprising against the Germans. She was responsible for organising a medical service in the area of Warszawa-Północ, i.e., northern districts of Warsaw,28 and had to establish first aid points and staff them with doctors and nurses, give theoretical and practical training courses for the nurses, collect and store medicines and dressings, make arrangements with hospitals to take in the wounded. Also, her private flat was used as a venue for underground meetings, storing materials and objects that were prohibited under Nazi German regulations (including weapons and explosives), and distributing underground broadsheets and other printed matter. Dr Jankowska provided shelter and treatment for wounded members of the resistance. For two long periods, her flat served as a hiding place for her Jewish fellow doctors and their wives.29 Later, when they moved to other safe houses, Dr Jankowska made sure they received parcels with food and clothing. For people on the German wanted list and expecting to be arrested at any time, she issued bogus medical certificates . . . , giving false names and phoney Warsaw addresses, to help them apply for new Kennkarten (identity cards issued by the German authorities). On two occasions she was warned by friendly women, one a complete stranger and the other a member of another underground organisation, that anonymous letters denouncing her had been sent to the Gestapo,30 but luckily they were intercepted by the Polish resistance (one message was spirited away from the premises of the Gestapo!). Nevertheless, Dr Jankowska did not stop working for the common good, although she implemented new security measures. Ultimately, however, she and her sister had to leave their flat, which was on the Hospital’s premises, and stayed with various friends until the outbreak of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. (Jaroszewski; see also Jarmużyński)

Dr Anna Kulikowska, who last saw Dr Jankowska in the autumn of 1940, wrote in her letter that she was

. . . very depressed by the situation in Poland and her personal trauma. She had already been informed of the death of her youngest brother, whom she had looked after when he was a child. Yet, she did not break down, but continued to be full of courage and determined to defy the enemy.

When the Warsaw Uprising broke out on 1 August 1944, from the very beginning of hostilities St. John’s Hospital again started admitting the wounded.

From Day One,31 the Hospital was under heavy fire. There were barricades in front of it, which provoked a Tiger tank to approach and hit both the barricades and the building several times, setting them ablaze. (Falkowski, 70)

Dr Jankowska was literally caught between two fires, because the Hospital was also attacked by an armoured train positioned at the nearby station Dworzec Gdański. The Germans started their bombing raids already in the first week of August. Dr Leon Uszkiewicz32 reported that from 13 August onwards, the situation was even more dangerous due to intense artillery fire and mortar shelling. The Hospital recorded fatalities right from the first day of the Uprising, when three mentally ill patients were killed. (Uszkiewicz)

The atmosphere of those dramatic days was vividly evoked by Janusz Jankowski, one of Dr Jankowska’s brothers:

Amid roaring guns, exploding bombs, shells, grenades, and rattling tanks, Warsaw’s best youngsters put up their desperate fight against all odds, challenging the ruthless enemy on the barricades and in the basements and cellars of collapsing houses. Hundreds of surgeons, assistant doctors, nurses, volunteer medics, and other helpers, usually elderly men, worked day and night for the two long months of the Uprising. I remember the operations that were carried out in the cellars of the Hospital, lit by tallow candles and with water in very short supply. I remember long lines of stretchers with those waiting for their turn on the operating table, but sometimes dying before they got there: I remember the old, grey-haired surgeons who kept operating until they fainted of exhaustion (Życie Warszawy 1963, Nos. 26 and 42). In the first aid point in the PWPW33 building, which was the fortress of the Uprising fighters stationed in the district of Stare Miasto,34 Dr Hanna Petrynowska35 worked indefatigably day and night for a whole month, operating wounded insurgents with the utmost dedication. She died a doctor’s death there on 1 September 1944.36 Her husband, Dr Marian Petrynowski, who had worked as a company doctor for the PWPW before the War, was deported in 1940 to Mauthausen37 and killed there three months later. PWPW was in the same area as St. John’s Hospital for the mentally ill. The Hospital . . . took in great numbers of those wounded in action in Stare Miasto, near Dworzec Gdański railway station, or in the operations against the armoured train positioned close to the walls of the ghetto. The doctors who worked round-the-clock in the Hospital building were both in-house psychiatrists and external surgeons.

Col. Stefan Tarnawski, nom de guerre Tarło,38 who was chief medical officer in the Stare Miasto district during the Uprising, testified before the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Nazi German Crimes in Poland39 as follows:

On 6 August 1944, I was assigned to serve in St. John’s Hospital, where I was ordered to establish a ward of forty beds for the seriously wounded, and I ran it for a few days. All the buildings on the hospital grounds were overfull, as crowds of patients were arriving all the time from the district of Wola and the neighbourhood of the ghetto as well as the immediate surroundings of the Hospital. We had a team of surgeons who worked day and night in very difficult conditions. They were led by Col. Dr Bronisław Stroński,40 Dr Krauze,41 and several in-house physicians. We had quite a lot of nursing staff and about 300 wounded patients. The situation was becoming more and more serious, because we were under incessant artillery fire on three sides. When two wings were razed to the ground, Prof. Falkowski42 gave me his permission to approach Col. Wachnowski,43 commander-in-chief in Stare Miasto, with a suggestion that the wounded and the surgeons’ team be moved further into the district. I was allowed to do that and commissioned to set up and manage new places for them. Field hospitals were established on the following streets: Freta, Długa, and Podwale.

Col. Tarnawski’s report can be supplemented with an excerpt from Dr Uszkiewicz’s notes:

From 7 August 1944, I was in St. John’s Hospital, which had about 300 wounded. The in-house physicians were Drs Szumigaj, Falkowski, and Lidia Wiśniewska. The external doctors were Stroński, Krauze, Wincenty Tomaszewski,44 Sadowski, Tarnawski. . . . Although the Hospital was clearly marked from the outside [with Red Cross signs] from the first day of the Uprising the Germans kept it under fire. (Uszkiewicz, col.1441-1442)

Since I have been using primary sources to describe the situation in St. John’s Hospital, where Dr Jankowska was working, let me also quote Prof. Adolf Falkowski:

I was head of St. John’s Hospital until 14 August 1944. On the 12th , the Command of the Uprising ordered the patients evacuated, because by that time the Hospital was on the frontline. . . . The combat operations I remember were the German attack on the Krasiński Palace from ulica Barokowa, the attack on the PWPW, and on the Hospital.

Let me provide one more quote from a still unpublished source:

Ever since the Hospital was put under heavy artillery fire, it had to make do without running water and electricity. Dr Jankowska was looking after the mentally ill as well as severely wounded patients. She assisted at operations, helped to carry patients from one place to another, and in general did all the routine chores. Despite the extreme danger, we finally managed to move all the wounded to the hospital at No. 7 on ulica Długa. However, it was impossible to transfer all the wounded and the mentally ill patients to somewhere safer. Dr Halina Jankowska, who did not want to abandon them, stayed behind and so did a few dedicated nurses, [Sister Eufemia] Izdebska and [Sister Julia] Kowalska.45 The rest of the staff were evacuated. Witnesses say that many people were calm and courageous. Yet it was Dr Jankowska who distinguished herself with her serenity, commitment, and heroism. She was urged many times to leave because the place was doomed, but even though she was extremely exhausted, she kept repeating she would stay with her patients until the end. (Jaroszewski and Ałapin)

Dr Franciszek Szumigaj says that when the Uprising broke out, an operating theatre was arranged in the tiled and fairly serviceable cellar of St. John’s Hospital. One day, when Dr Szumigaj was operating on a student of Gdańsk Technological University, actually amputating his arm, Dr Jankowska served as his assistant, so she held up the lamp and handed him the instruments. On many occasions, she helped the other surgeons, too. Although twenty-two years have passed, Dr Szumigaj still remembers her as a brave and spirited person, working hard non-stop.

We should also bear in mind that Dr Jankowska was looking after psychiatric patients, who continued to behave in their own ways and had been trapped in the Hospital since the beginning of the Uprising. Hanna Rewska, nom de guerre Renata,46 wrote in her diary:

I remember that one day I was either looking for something or wanted to talk to one of the nurses and I went down into the cellar [of the Hospital]. The corridors were dark and very narrow, and the tiny rooms overcrowded with wounded soldiers, mental patients, and civilians, attended by nuns. In the yard, and particularly in its front part, which was the vegetable garden, a few docile mental patients with cropped hair and carelessly shaven, would hang out in their unbuttoned shirts. They lazed away their time, absorbed in their own inner world, completely unresponsive to what was going on around them. They took no notice of the bomb blasts and the shrapnel and seemed completely unaware of the danger. A larger group of mental patients stayed in the right wing on ulica Konwiktorska. That room was full of usually quiet folk sprawled out on the tables and benches. (Rewska)

One of the mentally ill women, a young dancer, probably a Jewish woman from Hungary, seemed quite oblivious of the enemy fire and ran out into the garden. She started to dance; whirling about, she moved further and further into the shrubs and the dust. It was obvious she did not realise the situation was risky. Suddenly, when a shell exploded close to her, raising clouds of smoke and dirt, the blast tossed her up, giving her whirls even more momentum. Petrified witnesses watched as, in a split second, the body of their Salome eddied away in the air, shredded to pieces. She passed away dancing. (Szumigaj)

As the strategic situation of the fighters was becoming more and more desperate, those who stayed in St. John’s Hospital found it harder and harder to survive. Janusz Jankowski wrote the following account:

On 13 August the Germans started pelting the Hospital with artillery fire and the premises turned into a frontline position, and after 15 August both the wounded and the surgeons started to be evacuated. It was impossible to remove the mentally ill. Only the ward physician Dr Halina Jankowska and three utterly dedicated nurses, Eufemia Izdebska, Kazimiera Kobla,47 and Julia Kowalska, a group of insurgents and some other unknown heroes stayed by their side to the very end.

On 17 August the Hospital became the firing hideout for a platoon of the 1st Company of the Scouting Battalion Zośka,48 which was billeted in its cellar. It was more and more difficult for them to put out all the new fires, and on the night of 20-21 August the entire building was set ablaze after German missiles had ignited one wing and the conflagration spread throughout the Hospital. One of the soldiers made the following record in his diary:

I was the post commander, keeping guard on the entrance to the Hospital chapel with two more soldiers. . . . We had a group of military engineers inside doing repairs to the sewer that ran underneath the chapel, connecting it with the ghetto. . . . From time to time, the German artillery would dispatch a few “caskets” which landed on the roof with a buzz and swoosh. Some of them fell onto the burning roof of the Hospital. . . . Around noon on 21 August, the fire in the chapel burnt no more. (Szymanowski)

Hanna Rewska recorded the experience of the fighters of Battalion Marguerita,49 writing,

The night of 18-19 August. The premises of St. John’s Hospital, the first basement, left of the entrance on Sapieżyńska. Lots of people, general commotion and the hum of conversations. . . . The corridor was full of liaison girls and nurses, some even putting on provisional dressings. . . . If you wanted to go further in, for instance into the Hospital building as such, you had to go down another staircase into the cellars which led out onto the yard of another building, and eventually you were on ulica Sapieżyńska. The street was cut across by a trench that went straight up to the Hospital gates. So you waited until the fire subsided a bit and then you had to duck and run quickly to reach the other side. The gates to the Hospital yard were always guarded and you had to give the guards the day’s password. . . . 20 August. There were LMGs on the corner of the Hospital and Bonifraterska and, I suppose, on the corner of Bonifraterska and Sapieżyńska.

Before the Hospital came under immediate fire, the patients had been transferred to the cellars, which were equipped to serve as air raid shelters after the war started. The insurgents had firing positions on the overground floors to defend the building. Yet the underground rooms proved to be far from safe for the patients. And when the Hospital was hit by heavy missiles on 20 August, many wounded patients and some of the staff were buried under the debris. Some, though not all of the mentally ill patients, had been removed to another hospital on Freta. Those who stayed were under the care of Dr Halina Jankowska and Dr Franciszek Szumigaj. (Podlewski)

As Prof. Maria Grzegorzewska wrote, it was becoming obvious that these were the last moments for the Hospital as well. All the patients were told to disperse and save themselves, but some stayed, desperately clinging to the walls or keeping a firm hold of window frames, utterly terrified of the bleeding, burning, disintegrating world full of the hatred that broke loose when moral standards were discarded, and throbbing with people shrieking, the noise of detonating bombs and shrapnel, and the crash of collapsing houses. All the doctors had left the Hospital. Only she [Dr Jankowska] stayed behind with this group of frenzied people. Her colleagues urged her to hurry and leave immediately, as she would be unable to help her patients anyway—but all in vain. She did not hesitate even for a while. She wanted to stay with them, the sick people. There was no time to lose. Her fellow doctors had gone. Before long the roof of the Hospital collapsed. (Jankowski)

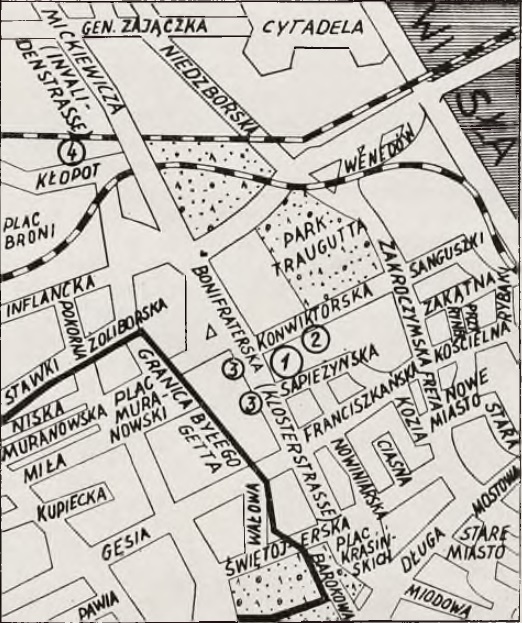

Part of the Warsaw city plan in 1944, showing St. John’s Hospital (1 = Hospital buildings, 2 = PWPW, 3 = closest German firing positions , 4 = Dworzec Gdański railway station). Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1967.

Hanna Rewska, an eye witness, said that from 23 to 26 August the Germans continued to storm the Hospital as they wanted to break the Polish resistance at this point regardless of the costs. The air raids stopped only at night and the infamous Nebelwerfers50 kept shooting more and more fiercely. It was the last phase of fighting in the Stare Miasto district.

The defenders huddled in small groups isolated from each other and surrounded by enemy forces. The Polish units in the neighbourhood of the Hospital had twenty doctors and even fewer qualified nurses, which meant that they could not provide proper medical care for the 6,000 wounded. The doctors worked practically non-stop and the surgeons had to overcome their tiredness, going without sleep and hardly ever leaving the operation rooms. In the last days of August everybody realized that the situation was hopeless. It had been hard enough to get by without electricity, but now many more things were becoming scarce: food, water, medicines, and even dressings. On the night of 29-30 August, Colonel Wachnowski, commander-in-chief in Stare Miasto, decided to make a desperate attempt to cross the ruins back to Śródmieście. However, this offensive move manned by a handful of fighters proved unsuccessful—they were vastly outnumbered by the Germans. (Tarnawski)

By that time Dr Jankowska was dead.

At 6 a.m. on 23 August 1944, artillery fire crushed the remaining roofs and ceilings [of the Hospital] over the rooms where the wounded and the mentally ill, Dr Jankowska and the nurses were. They were killed by the falling debris. (Jaroszewski and Ałapin)

According to Stanisław Podlewski, over 300 severely wounded people were killed apart from Dr Jankowska and the psychiatric patients. (Podlewski, 640)

Dr Jankowska did not manage to evacuate with the rest of the patients. Today it would be difficult to speculate about her motives and try to judge her, or even conjecture about the circumstances that influenced her decision. Actually, at the beginning some of the staff of the Hospital expected that the Uprising would soon be over and the situation would stabilise. These expectations were soon frustrated and the people trapped in the heavy fighting must have known it. On the other hand, for a few days51 the doctors knew there were escape routes and were probably tempted to save themselves. Dr Szumigaj had already relocated on his superiors’ orders to a temporary hospital in the Church of St. Hyacinth: he was appointed head of that establishment and could not abandon his wounded patients.

Dr Jankowska stayed to care for her patients, because her conscience and sense of moral duty told her to do so. The vaults of the cellars where she had been hiding with her brood finally caved in, shattered by bombs and gutted by fire. She and her wards were buried under the rubble, crushed to death by falling debris. (Szumigaj)

Leon Uszkiewicz, whom I have already mentioned, reported that a railway worker, whose name he did not provide, said that “when the Germans entered the Hospital on 26 August 1944, those patients who were able to walk unassisted were ordered to move to the district of Żoliborz.” Adolf Falkowski stated that the members of the nursing staff of the Hospital who stayed behind were Sister Jadwiga Paszkowska,52 a Daughter of Charity, and the paramedic Feliks Rozumek. (Falkowski, Statement)

The body of Dr Halina Jankowska was discovered in the rubble, on the corner of Konwiktorska and Bonifraterska, where she had died. (Jaroszewski and Ałapin) A manuscript of her last paper was also found there, but the title was illegible. (Filar) Later this paper was lost. After Dr Jankowska’s body had been exhumed, her funeral was held on 15 January 1947 in the Powązki Military Cemetery. She was buried in the Battalion Gustaw section, as some of its soldiers had been in her care. (Jaroszewski and Ałapin)

Dr Halina Jankowska was posthumously awarded the Cross of Valour.53 To commemorate her, the Toruń Voivodeship54 Mental Health Centre (at No. 24, ulica Mickiewicza) named its psychiatric ward after her. The ward was established by Dr Mastalerz-Wilkansowa and Dr Z. Chmielewska. In the years following the War, Dr Jankowska was hardly ever mentioned on the public forum. Twenty-two years after the War,55 we still do not have a comprehensive volume about her life. Only occasional, brief texts have been published about her. Dr Jankowska was paid the tribute she deserved on the 15th anniversary of her death. Memorials were held both on the site of the Hospital ruins and in the Powązki Cemetery. On 6 November 1963 her brother Janusz Jankowski sent a letter to the Board of ZBoWiD,56 pointing out that the place where Dr Jankowska had died was not on the official list of sites where during the war Polish people had fought heroically and been killed. He was promised that it would be put on the supplement list. It should be noted that thirteen years ago Prof. Andrzej Jus,57 who was acquainted with the life and achievement of Dr Jankowska, published an article commending her in a Soviet medical journal.

Photo of the ruins of St. John’s Hospital, 1959. The building on the left is the reconstructed church of the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1967.

Readers may see a cross next to the ruins of the Hospital on Konwiktorska.58 It was erected to commemorate the tragic events of the 1944 Uprising. On the 15th anniversary of Dr Jankowska’s death, Zdzisław Jaroszewski delivered a speech on the site, referring to her as a “lasting symbol of what we should do for patients.” On his initiative, the 27th Congress of Polish Psychiatrists voted a resolution to support “the efforts of the Executive Committee of the Warsaw City Council to finance a plaque commemorating Dr Halina Jankowska.” (Pamiętnik) The Main Board of the Polish Psychiatric Association suggested that Konwiktorska should be renamed in honour of the heroic doctor. (Jaroszewski and Ałapin) That request could not be granted as the regulations stipulate that the historical names of Warsaw’s old streets ought to be preserved. Perhaps, as suggested by the Warsaw branch and the Main Board of the Polish Psychiatric Association, a plaque could be put up on Bonifraterska, saying: “This is the place where in 1944, during the Warsaw Uprising, DR HALINA JANKOWSKA died a heroic death in the debris of St. John’s Hospital. She was a psychiatrist and head of that Hospital, posthumously awarded the Cross of Valour. Her companions in death were her patients as well as the nurses from the Congregation of the Daughters of Charity and other Hospital staff. This plaque was funded by the Executive Committee of the Warsaw City Council and the general public in recognition of the victims’ achievements and in memory of them.” (Jaroszewski and Ałapin)

***

I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to the people who were so kind as to furnish me with detailed information about the life of Dr Halina Jankowska and helped me to access sources and collect materials: Prof. Maria Grzegorzewska, Dr Anna Kulikowska, Janusz Jankowski, Dr Zdzisław Jaroszewski, Dr Marian Marzyński, and Dr Franciszek Szumigaj.

***

Translated from original article: Dominik, M. “Dr Halina Jankowska.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1967.

Notes

- Janusz Korczak (1878–1942; real name Henryk Goldszmit, nickname Stary Doktor, “Old Doctor”), Polish-Jewish physician, educator, writer, and social activist. He joined the children from his orphanage on their last journey from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Source: Polski Słownik Biograficzny (hereinafter PSB), 1959-1960, Vol. 8.a

- Maksymilian Kolbe (1894–1941), Polish Franciscan friar. Established the Militia Immaculatae, a Catholic evangelization movement. The first Polish Catholic martyr in the Second World War. Volunteered for death by starvation in Auschwitz to save a fellow inmate’s life. Canonised in 1982. Source: PSB, 1968, Vol. 13.a

- The Warsaw Hospital of St. John of God was founded in 1650 by the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God. In 1862 it acquired a psychiatric ward. The Hospital was razed to the ground during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. Source: Kaczorowski, Bartłomiej, ed., 1994, Encyklopedia Warszawy, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.a

- Now Berdichiv, Ukraine.b

- Its founder later bequeathed the school to the Polish State and it is now known as X Liceum Ogólnokształcące in Warsaw.b

- Established in 1897 by Vassily von Anrep, a Russian physician, physiologist, and pharmacologist. See Steve M. Yentis and Kamen V. Vlassakov. Vassily von Anrep, Forgotten Pioneer of Regional Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. March 1999, Vol. 90, 890–895.a

- Now Vinnytsia, Ukraine.b

- Tworki Hospital was founded in 1891 on the initiative of Prof. Adolf Rothe and other Polish psychiatrists and community workers. It is situated in Pruszków, a small town near Warsaw. Source: Bartłomiej Kaczorowski, ed., Encyklopedia Warszawy, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994.a

- Witold Łuniewski (1881–1943), Polish psychiatrist. Founder of the Polish school of forensic and penitentiary psychiatry. Established and headed a mental hospital in Warka. Head of Tworki mental hospital, 1919–1939. Source: PSB, 1973, Vol. 18.a

- Now Vilnius, Lithuania.b

- Antoni Mikulski (1872–1925), professor of psychiatry at the Stephen Báthory University in Wilno. Founder of Polish clinical psychiatry. Authored a handbook of psychiatry. Source: PSB, 1976, Vol. 21.a

- Rafał Radziwiłłowicz (1860–1929), Polish psychiatrist and psychologist, professor at the Stephen Báthory University in Wilno. One of the founders of the Polish Psychiatric Association. Source: Kosnarewicz, Elwira et al., 1992, Słownik psychologów polskich, Poznań: Zakład Historii Myśli Psychologicznej. Instytut Psychologii UAM Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza.a

- Maksymilian Rose (1883–1937), Polish neurologist, neuroanatomist, and psychiatrist. Assistant professor of neurology at the University of Warsaw (1928). Professor at the Stephen Báthory University in Wilno and head of the Chair of Psychiatry (1931). Co-founder and first head of Polski Instytut Badań Mózgu (the Polish Institute for Brain Research). Source: PSB, 1989/1991, Vol. 32, fascicle 1.a

- Michał Marzyński (1900–1970), Polish psychiatrist. Worked in the Kochanówka mental hospital in Łódź, in the Hospital for Nervous and Mental Diseases of the Stephen Báthory University in Wilno, and the hospital at Kojrany near Białystok. Appointed to a post in the Psychiatric Hospital of the University of Łódź in 1949.a

- We have not been able to identify this place; the place name has probably been misspelled.b

- Medal Dziesięciolecia Odzyskanej Niepodległości, a Polish civilian decoration founded in 1928 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the restoration of Polish independence. Awarded to citizens for distinguished service to the Polish State.a

- The original titles of the papers listed here are as follows: “Przypadek psychozy urojeniowej w przebiegu parkinsonizmu pośpiączkowego,” “Przypadek parafrenii rozwijającej się po przebytym zespole sensytywnym urojeń ksobnych Kretschmera,” “Przypadek ostrej omamowej psychozy alkoholowej,” “O depersonalizacji w omamach,” “Z zagadnień biologii wzruszeń,” “Przypadek niemoty czuciowej przy lewostronnym porażeniu,” “Napady osłupienia negatywistycznego w przebiegu tabo-paralysis,” “Przyczynek do zagadnienia dziedziczności w dystonii torsyjnej,” “Poziom inteligencji dzieci szkół powszechnych miasta Wilna,” “Opieka rodzinna nad psychicznie chorymi na Wileńszczyźnie,” and “Badanie sprawności czynności wątrobowej w padaczce.”b

- Instytut Pedagogiki Specjalnej, founded in 1922 following the merger of two earlier institutions for special education. Now known as Akademia Pedagogiki Specjalnej im. Marii Grzegorzewskiej (the Maria Grzegorzewska University).a

- Maria Grzegorzewska (1887–1967), psychologist and educator. Pioneer of special education in Poland and first head of the Institute of Special Education. Source: Kosnarewicz, Elwira et al., 1992, Słownik psychologów polskich, Poznań: Zakład Historii Myśli Psychologicznej. Instytut Psychologii UAM Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza.a

- I.e., in 1967.b

- Franciszek Szumigaj (1906–1978), Polish surgeon. Second-in-command of the Hospital of St. John at Bonifraterska 12 during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising; later a physician of No. 1 Surgical Hospital at Długa 7 and commander of its branch in the Church of St. Hyacinth at Freta 10. Source: www.szpitale1944.pl.a

- Not to be confused with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943. The Warsaw Uprising of 1944 broke out on 1 August and continued until the first days of October of that year.c

- Odrodzenie was a Catholic youth organisation in pre-war Poland.c

- Spójnia was an unofficial association of Polish women students in St. Petersburg, which had a large Polish community in the 19th and early 20th century, when a large part of Poland was ruled by the Tsar of Russia following Poland’s loss of independence in 1772–1795 and dismemberment by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Spójnia was founded in 1909 as a grass-roots initiative. Its aims were to provide aid for women students, train members for community work and political activities, and spread awareness of women’s emancipation. Source: www.polskipetersburg.pl.a

- Jerzy Zawieyski (1902–1969), Polish playwright, novelist and essayist, politician with Catholic views, parliamentary deputy to the Polish Sejm under the People’s Republic of Poland, 1957–1969.a

- The Germans sent them to concentration camps or euthanasia centres in Germany.b

- Zdzisław Józef Jaroszewski, nom de guerre Józef Morawski (1906–2000), Polish psychiatrist. After the War, head of the Kocborowo mental hospital in Starogard Gdański and the mental hospital at Drewnica near Warsaw. Source: Fundacja Generał Elżbiety Zawackiej, AK Okręg Pomorze 1939–1945 (the documentation can be accessed online under the link).a

- Towards the end of the War, Armia Krajowa (the Home Army), the largest underground resistance force in Poland and the whole of occupied Europe, planned Akcja Burza (Operation Tempest) to liberate German-occupied cities. It started simultaneously in many regions of occupied Poland when Soviet forces crossed the eastern border of pre-war Poland (in January 1944); and continued until January 1945. The Warsaw combat area included the city of Warsaw and its environs, and was divided into six districts (Śródmieście, Żoliborz, Wola, Ochota, Mokotów, Praga), with Okęcie Airport as an independent area. A similar division was adopted within the medical service of the Home Army. Warszawa-Północ, “Warsaw-North,” probably refers to Grupa Północ (“Group North”), a Home Army unit commanded by Karol Ziemski, nom de guerre Wachnowski, which operated in the districts of Kampinos, Żoliborz, and Stare Miasto. The term was introduced by Col. Antoni Chruściel, nom de guerre Monter, commander of the Polish forces in the Uprising. Sources: Kirchmayer, Jerzy, 1984. Powstanie Warszawskie, Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza; Bayer, Stanisław, 1985, Służba zdrowia Warszawy w walce z okupantem 1939–1945, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo MON.a

- Under the Nazi German regulations imposed in occupied Poland, any Pole offering any form of assistance to a Jew (not to mention harbouring Jews) was automatically liable to a death sentence.c

- The Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei) was the secret police force of the Third Reich, established on 26 April 1933. It resorted to the harshest measures to eliminate all political resistance. Disbanded in 1945, after the capitulation of Nazi Germany. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestapo.a

- The Uprising lasted for 63 days, from 1 August to 3 October 1944.c

- Leon Uszkiewicz (1905–1953), Polish psychiatrist. Head of St. John’s Hospital during the 1944 Uprising. After the War, head of the medical publishing house Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich and editor-in-chief of the medical journal Służba Zdrowia.a

- PWPW, Państwowa Wytwórnia Papierów Wartościowych, (the Polish Security Printing Works) founded in 1918, printed banknotes, securities, and special documents. During the Nazi German occupation, Polish resistance forces used its facilities clandestinely to print paper money and false identity documents. During the 1944 Uprising, the building was taken over by the insurgents, who managed to keep it for a month.a

- The Old Town, colloquially called Starówka.b

- Hanna Petrynowska, nom de guerre Rana (1901–1944), Polish paediatrician. During the 1944 Uprising she set up a first aid point in the PWPW building. Shot by German soldiers while operating on a patient. Her nurses and thirty wounded Poles were also killed. Source: www.1944.pl.a

- Dr Petrynowska was killed on 28 August 1944.a

- Mauthausen was a Nazi German concentration camp about 20 km from Linz in Austria. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mauthausen_concentration_camp.c

- Stefan Tarnawski, nom de guerre Tarło (1898–2001), Polish army doctor. One of the commanding officers in the Home Army medical service. Served during the 1944 Uprising as chief medical officer for Grupa Północ. After the fighters evacuated to the district of Śródmieście via sewers, from 5 September 1944 he was commander of the field hospital at Śniadeckich 17. Also, he managed the Sano hospital at Lwowska 13 and the field hospital at Lwowska 17. When the Uprising fell, he and the wounded soldiers were relocated to Kraków, where he became the commander of the evacuated Ujazdowski Hospital. Sources: www.1944.pl; www.lekarzepowstania.pl.a

- Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce. These records are now preserved in the collections of the Institute of National Remembrance.c

- Bronisław Stroński (1887–1952), surgeon, colonel in the Polish Army. Took part in the 1920 war against Bolshevist Russia. During the 1944 Uprising worked for the Home Army medical service in the Warsaw area and Grupa Północ, St. John’s Hospital, and No. 1. Surgical Hospital at Długa. When the Polish forces relocated to the district of Śródmieście via sewers, he and Dr Adolf Falkowski worked in a makeshift hospital in the Japanese embassy on Pierackiego. When the Home Army capitulated, he left Warsaw with the civilians. Until the end of the War, he worked in a Polish Red Cross dispensary in Grodzisk Mazowiecki. Sources: www.szpitale1944.pl, www.lekarzepowstania.pl.a

- Antoni/Artur Krauze (the sources give either of these names) was a doctor of the Hospital of St. John of God and No. 1 Surgical Hospital on Długa. Source: www.szpitale1944.pl.a

- Adolf Falkowski (1886–1963), Polish psychiatrist. In 1919–1921 he worked in St. John’s Hospital in Warsaw. Assistant professor in the Chair of Neurology of the Stephen Báthory University in Wilno, 1923–1930. Head of Kochanówka mental hospital in Łódź, 1930–1934. Commanding officer of St. John’s Hospital during the 1944 Uprising, and later of No. 1 Surgical Hospital. Evacuated to the district of Śródmieście with Dr Bronisław Stroński, where he worked in the hospital on Pierackiego and St. Roch’s Hospital, which was captured by the Germans. Left Warsaw with the civilians. Source: www.1944.pl.a

- Karol Ziemski, nom de guerre Wachnowski (1895–1974), colonel in the Polish Army. Took part in the 1920 war against Bolshevist Russia and the defence campaign against the Germans in 1939. During the 1944 Uprising second-in-command to Antoni Chruściel, nom de guerre Monter, who appointed him commander of Grupa Północ on 7 August 1944. Lived in exile after the War. Source: www.1944.pl.a

- Wincenty Tomaszewicz (erroneous surname “Tomaszewski” in the Polish text; 1876–1965), Polish surgeon. During the 1944 Uprising worked in St. John’s Hospital and No. 1 Surgical Hospital. When the Polish forces left the district of Stare Miasto, he was evacuated from Warsaw with the civilians and imprisoned in a transit camp at Pruszków. Released due to old age. Source: www.1944.pl.a

- Sister Eugenia Lucyna Izdebska (1888–1944) and Sister Julia Kowalska (1887–1944) were Daughters of Charity and worked as nurses in St. John’s Hospital. They died either on 23 August 1944 in one of the bomb attacks on Stare Miasto or were killed by the Germans on 30 August 1944 with about 300 patients and members of the staff. Sources: https://www.1944.pl/powstancze-biogramy.html; http://www.swzygmunt.knc.pl/MARTYROLOGIUM/POLISHRELIGIOUS/vPOLISH/HTMs/POLISHRELIGIOUSmartyr0953.htm.a

- Hanna Rewska, nom de guerre Renata (1915–1970; real name Anna Sarzyńska-Rewska), member of special commando Dysk in the Kedyw (sabotage and subversion) unit of the Home Army. On 1 February 1943 she took part in the successful assassination of SS Brigadeführer Franz Kutschera, the “hangman of Warsaw.” During the 1944 Uprising she served in Battalion Zośka. Political prisoner after the War; the Communists sentenced her to prison for contact with émigré journalist and editor Jerzy Giedroyć. Sources: PSB, 1988–1989, Vol. 31, fascicle 128; www.1944.pl.a

- Sister Kazimiera Kobla (1898–1944), Daughter of Charity, nurse in St. John’s Hospital. Exact date of death unknown (see comment on Sr. Eugenia Izdebska and Sr. Julia Kowalska).a

- Battalion Zośka, established in 1943, a scouting unit of the Home Army. Named after Tadeusz Zawadzki, nom de guerre Zośka, commander of an assault group, killed in action. During the 1944 Uprising, Battalion Zośka was part of the Radosław Group and fought in Wola, Stare Miasto, Czerniaków, and Mokotów. Source: Kamiński, Aleksander, 2009, “Zośka” i “Parasol.” Warsaw: Iskry.a

- Probably the unit commanded by Maria Jankowska, nom de guerre Margerita, part of the women’s special commando Dysk, formed in the spring of 1940.a

- The Nebelwerfers (“smoke mortars”) were a series of German guns used to shoot artillery shells. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nebelwerfer.c

- The last days before the final attack.b

- Sister Jadwiga Paszkowska was a Daughter of Charity and nurse in St. John’s Hospital. She stayed with the wounded even after the fighters had evacuated the district. After the War she worked in the pharmacy of the Infant Jesus Hospital in Warsaw. Source: www.1944.pl.a

- Krzyż Walecznych.b

- The first-tier territorial division in Poland is called a voivodeship.c

- The article was originally published in 1967.b

- ZBoWiD, Związek Bojowników o Wolność i Demokrację (the Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy), the main Polish war veterans’ association under the People’s Republic.c

- Andrzej Jus (1914–1992), Polish psychiatrist, head of the Psychiatric Hospital of Warsaw Medical University. He and his wife were pioneers of research on electroencephalography.a

- As of 2021, there is a new hospital on the site, run by the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God. The new hospital was founded in the mid-1990s. See https://bonifratrzy.pl/centrum-medyczne-bonifratrow/o-nas/historia/. For a photo of the ruins of the Hospital viewed from Konwiktorska, see https://polska-org.pl/8437858,Warszawa,Szpital_bonifratrow_sw_Jana_Bozego_dawny.html. For the site today, viewed from the opposite side of Bonifraterska, with the new hospital on the right of the church, see https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kościół_Św._Jana_Bożego_w_Warszawie#/media/Plik:Kościół_Św._Jana_Bożego_w_Warszawie_2017.jpg.c

a—notes by Anna Marek, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Marta Kapera, the translator of the above article; c—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

Publications

Bilikiewicz, Tadeusz, and Gallus, Jan. 1962. Psychiatria polska na tle dziejowym, Warszawa: PZWL, 225-231.

Falkowski, Adolf, “Szpital św. Jana Bożego w latach 1939-1944,” Rocznik Psychiatryczny 1949: XXXVII, 1, 67-74.

Falkowski, Adolf. Statement made on 7 November 1947 before the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes in Poland (Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce. Akta w sprawie zbrodni hitlerowskich w okresie powstania warszawskiego VI file 1100, columns 1443-1444; now preserved in the records of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance). See Falkowski’s statement in Chronicles of Terror, online athttps://www.chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=606&navq=aHR0cDovL3d3dy5jaHJvbmljbGVzb2Z0ZXJyb3IucGwvZGxpYnJhL3Jlc3VsdHM_cT1GYWxrb3dza2kmYWN0aW9uPVNpbXBsZVNlYXJjaEFjdGlvbiZtZGlyaWRzPSZ0eXBlPS02JnN0YXJ0c3RyPV9hbGwmcD0w&navref=aDk7Z3UgOGxjOzhqaCAyc3I7MnM4IGljO2h4IDJzcTsyczcgM3dzOzN3MCBudTtuZiBneTtnaiBwMDtvbCAzZTQ7M2RlIGk5O2h1IDZqOzY3IGdqO2c0&format_id=6

Filar, Zbigniew. 1962. “Jankowska, Halina.” Polski Słownik Biograficzny X, 530-531.

Grzegorzewska, Maria, 1958. Listy do młodego nauczyciela. Cykl II, Warszawa: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych, 8-9.

Jarmużyński, Bolesław, “Pamięci bohaterów b. Szpitala Jana Bożego,” Życie Warszawy, 1959: 197.

Jus, Andrzej. “Состояние польской психиатрии,” Журнал невропатологии и психиатрииим. С.С. Корсакова 1953: 7, 527.

Łoza, Stanisław, ed. 1939. Czy wiesz, kto to jest? Warszawa: Główna Księgarnia Wojskowa, 286.

Pamiętnik XXVII Zjazdu Naukowego Psychiatrów Polskich (Proceedings of the 27th Congress of Polish Psychiatrists). 1963. Kraków, 234 and 262.

Podlewski, Stanisław. 1957. Przemarsz przez piekło, Warszawa: Pax, 253.

Tarnawski, Stefan. Statement made on 31 December 1947 before the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes in Poland (Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce. Akta w sprawie zbrodni hitlerowskich w okresie powstania warszawskiego VI file 1100, column 1447; now preserved in the records of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance). See Tarnawski’s statement in Chronicles of Terror, online at https://www.chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=595&navq=aHR0cDovL3d3dy5jaHJvbmljbGVzb2Z0ZXJyb3IucGwvZGxpYnJhL3Jlc3VsdHM_cT1UYXJuYXdza2kmYWN0aW9uPVNpbXBsZVNlYXJjaEFjdGlvbiZtZGlyaWRzPSZ0eXBlPS02JnN0YXJ0c3RyPV9hbGwmcD0w&navref=Z3k7Z2ogaWM7aHggaTk7aHUgMWp6OzFqaCAzMTM7MzBq&format_id=6

Uszkiewicz, Leon. Statement made on 23 December 1947 before the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes in Poland (Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce. Akta w sprawie zbrodni hitlerowskich w okresie powstania warszawskiego VI file 1100, columns 1441-1442; now preserved in the records of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance). See Uszkiewicz’s statement in Chronicles of Terror, online at https://www.chroniclesofterror.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=645&navq=aHR0cDovL3d3dy5jaHJvbmljbGVzb2Z0ZXJyb3IucGwvZGxpYnJhL3Jlc3VsdHM_YWN0aW9uPUFkdmFuY2VkU2VhcmNoQWN0aW9uJnR5cGU9LTMmc2VhcmNoX2F0dGlkMT02NCZzZWFyY2hfdmFsdWUxPVdhcnN6YXdhLCUyMHVsLiUyMFBvZHdhbGUlMjAyNSUyMCZwPTA&navref=aWY7aTAgcDI7b24gaWE7aHYgcGc7cDEgaWM7aHggaWc7aTEgNDI1OzQxYw&format_id=6

Zawieyski, Jerzy. 1958. “Droga katechumena,” Znak 10, (43), 28.

Letters, manuscripts and personal communications

Jankowski, Janusz. “Pamięci bohaterskich lekarek i pielęgniarek powstania,” typescript.

Jaroszewski, Zdzisław, and Ałapin, Bolesław (signatories). Letter from the Main Board of the Polish Psychiatric Association to the Executive Committee of the Warsaw City Council of 4 March 1959, Ref. No. 30/59-12.

Jaroszewski, Zdzisław, personal communication.

Jaroszewski, Zdzisław, unpublished note.

Kulikowska, Anna. Letter of 20 June 1966 to the editors of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

Marzyński, Michał. Diary (manuscript).

Rewska, Hanna, “Pamiętnik powstania warszawskiego 1944, spisany przez uczestniczkę batalionu Marguerita.” Manuscript in the collections of the National Library, Warsaw, shelf no. 7852, p. 102.

Szumigaj, Franciszek, personal communication.

Szymanowski, Wojciech (nom de guerre J. Rafałowski). “Szlakiem Zośki.” Manuscript and typescript No. 7946 III, preserved in the National Library in Warsaw.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.