Author

Leon Głogowski, MD, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor No. 1281, author of first-hand testimonies and studies on concentration camp history and medicine published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Read his biography under the link.

Although I was a physician, I had a clerk’s job in the hospital’s office. I was fluent in German and was needed there.

In January 1942, I was selected for an experimental group to test a new typhus vaccine. The Germans were looking for an efficient method of prevention, because more and more of them were going down with typhus. In point of fact, we were quite happy to be inoculated, since Weigel’s vaccine was hard to obtain in large quantities. But we had not been informed that we were being given an experimental vaccine and that we were the first guinea pigs on which it was being tested.

I was working in the Schreibstube1 for another nine days following the inoculation, and on the ninth day I got an extremely violent headache: it felt like every single hair on my head was sore. I complained to my fellow inmates and my friend Wojciech Barcz replied that my problem was obviously Haarwurzelkatarrh, the burning scalp syndrome. I had to lie down. The other doctors gave me a pill. As far as I can remember, on the following day there were several doctors at my bedside, then I was laid on a stretcher, and then I passed out. I regained consciousness after twenty-one days and my colleagues told me what had happened in that time.

I was admitted to hospital by Dr Jan Pakowski, who wanted to administer a strong dose of sulphonamides. As I was not thinking clearly, I resisted, shouting that the doctors were trying to poison me. Therefore Dr Pakowski dissolved a large number of red tablets and gave me an enema. I had a few red-coloured stools but was otherwise flat out, unable to leave my bed, eat or drink. It must have been very difficult to take care of me. After a few days, I showed symptoms either of inflammation of the middle ear or meningitis: I brought up my left arm towards the left parietal bone at roughly regular intervals. A specialist consultant, the otologist Dr Wasilewski, was called. He punctured my eardrum, but no pus showed up. Therefore Dr Pakowski performed a lumbar puncture, removing a considerable amount of cerebrospinal fluid, and happily observed that the involuntary repetitive movements of the arm were becoming less frequent. I would certainly have not survived twenty-one days without food and drink if it had not been for Dr Pakowski’s help, who gave me daily hypodermic injections of fluids in my thigh.

On the eighteenth day of my illness, my prognosis must have been really poor since formal preparations were started for notification of death. However, Dr Pakowski continued his treatment and on the twenty-first day, surprisingly, a patient whose bed stood opposite mine summoned him, because, as he said, he had seen me blinking. A few hours later, I was asked if I wanted to eat or drink something. Apparently I asked for a beer—and got it! Of course, you had to have very many friends to smuggle such a drink into the camp.

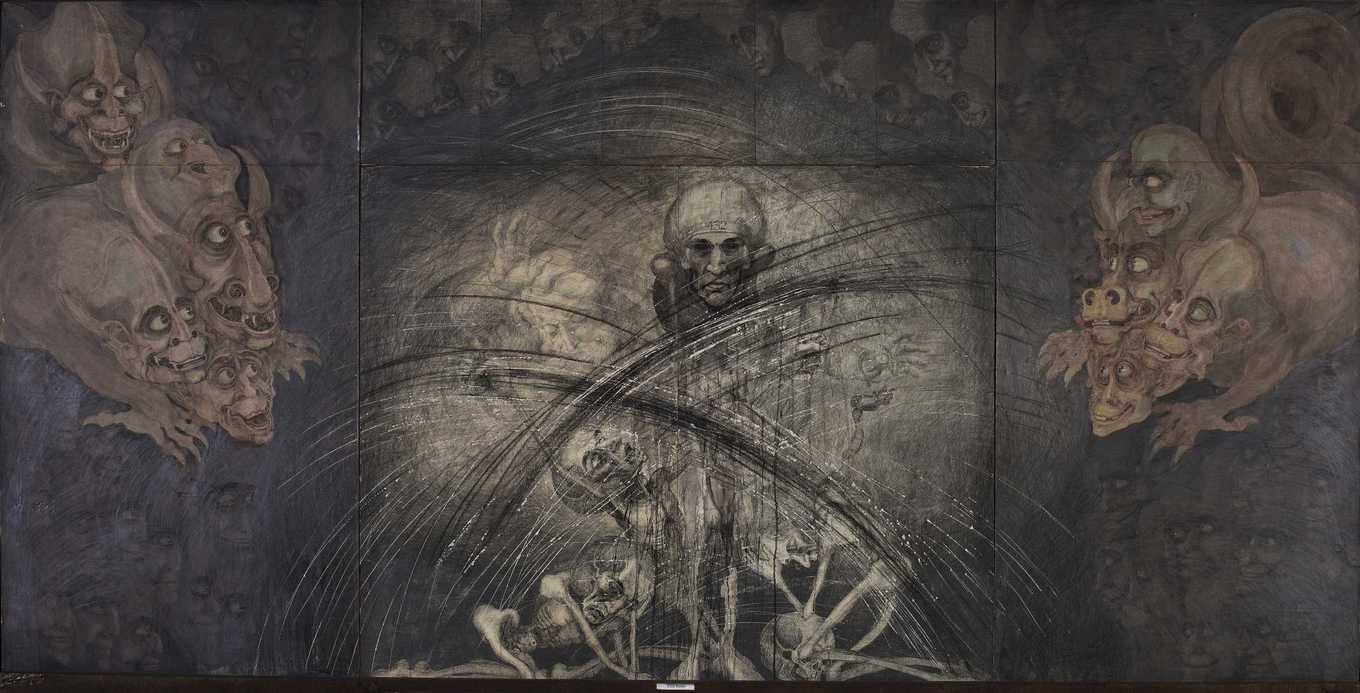

Ecce Homo. Artwork by Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click the image to enlarge.

Though I was conscious again, I was not a pretty sight. My skin was completely covered in almost purple spots. The other patients had lost them much earlier. Also, my epidermis and dermis were very dry and when a skin fold was lifted, it stayed in place, which is a symptom of dehydration. I was completely exhausted and emaciated, my arms and legs seemed not to have any muscle left on them. I must have weighed under 36 kilos [79 lbs.]. Sitting up was out of the question. My colleagues teased me jokingly, enquiring what I had been up to for the preceding three weeks. I told them about the nightmares that I had been suffering from during the recent nights, dreaming about a tunnel which I had to dig through high mountains.

Afterwards, I was constantly hungry. All the food that my fellow prisoners brought in in the morning was gone by the evening. One morning, Alojzy Sosna gave me a piece of what looked like sausage, and in the evening I grumbled about not having been provided with any victuals. Provisions were also delivered by Wincenty Mięsok, who worked in the SS storerooms, and Wacek [Wacław] Kolonko, who had a job in what was dubbed “Canada.”2 He said they even had lemons there. The difficult thing was to smuggle them into the camp. All the work commandos were always scrupulously searched at the perimeter when entering the camp after a day’s work and a prisoner caught with any contraband was punished with Stehbunker3 or being slung up on the post. So I sewed a genital supporter for Wacek to smuggle in some fruit for me every day, which in practice amounted to risking his own life. I was desperately clinging on to my life, begging for any vitamins and dietary supplements that could be found in “Canada.” For instance, a bottle of cod-liver oil would not last me longer than four days.

But as soon as I was able to sit up and walk a few steps, I got an unpleasant surprise. I felt an acute pain on the left side of my chest and had difficulty breathing. Dr Pakowski diagnosed me with dry pleurisy and procured some calcium injections. Within a few days, the pain was gone, but the pleural cavity had filled up with so much fluid that the mediastinum was pushed over to the right side of the chest. Again, I was disabled, unable to breathe, and physically exhausted. I had to stay in bed. Every day, I received intravenous injections in precisely the same vein, because my bunk could be accessed only on one side. Some doctors suggested thoracentesis, but I relied on the opinion of Dr Pakowski, who said it was impossible to guarantee absolutely sterile conditions for the procedure. For the time being, though the amount of excess fluid was high, I was not running a temperature.

Indeed, my pleural effusion slowly subsided, I must have sweated the fluid out. The only problem was I was not gaining enough weight. A month had passed and I weighed just 43 kilos [94 lbs.]. And just when I thought I was recovering and started feeling better emotionally, misfortune struck again. I developed a heart condition: after any gentle exercise I had dyspnoea and my pulse stayed at over 140 beats per minute. I broke down. We were allowed to write letters home and I wanted to send one, but my handwriting was appalling. I could not have imagined that writing a letter could be so strenuous. As my mother kept all my letters, she must have realized when she read the scrawled words and analysed the contents that something bad had happened in the previous month.

My convalescence was spinning out. Although I was still registered as an inpatient, I had to supervise the other sick men in my room. From day to day, I was able to walk a few more steps. The Lagerarzt,4 either Wutke5 or Entress,6 took a personal interest in my health, which was not unmotivated. On several occasions, I was observed by the SS doctor while I was doing my office job. One day, I was presented with a plan of work that I was supposed to carry out. I had to use one room to accommodate patients in the initial stages of pneumonia and then administer medications as ordered by him, run lab tests and X-rays, and make a written record in the proper form of the course of the illness.

A room was assigned for the purpose and the Lagerälteste71 appointed the orderlies. I received new patients with pneumonia who had just been admitted. I did my job as instructed, even though at the beginning I was distrustful. The white tablets turned out to be a new sulphonamide, which almost always successfully treated pneumonia within a few days. I wrote down the medical histories very carefully and the Lagerarzt was very pleased; I supposed he needed the results to write his doctoral dissertation.

I tended to delegate my responsibilities and stayed in my room, because walking over to a block across the street was a huge effort. It was difficult for me to recuperate. We were very poorly fed: our daily rations contained less than 1,000 calories. For three months in a row, we were never given any potatoes. Every day, our lunch was just swedes. Groats or meat, in any form, were an impossible dream. So, the support I received from my friends from Rybnik, that is Mięsok, Sosna, and Kolonko, who worked outside the camp, and Mięsok even in an SS storeroom, was invaluable.

Auschwitz only got a new consignment of potatoes in early April, and then potatoes were our staple food. Every prisoner tried to wangle a few and eat them raw, furtively, not bothering to boil them. Prior to incarceration, I would never have thought it possible. A prisoner’s portion of soup contained one unpeeled potato and our tea was made of blackberry leaves: it was well-nigh black and tasted awful.

The conditions might have been slightly less unbearable but for one inconvenience. Sometimes the patients who were brought into the ward had not been disinfected. As a rule, they were unconscious and bedridden for at least nine days. In the meantime, the fleas they were riddled with proliferated, biting us so badly that we could not have even a few hours of unbroken sleep, despite exhaustion. Every evening, we would kill at least five hundred insects. They stuck to the fibres of the blankets and were hard to pull out, so I crushed them with a metal object. However, all that effort was in vain if the other patients did not de-flea their blankets too. At night, when I could not stand it any longer, I would sit up on a plank which I had extended from one bunk to another. The proliferating fleas were a great nuisance to prisoners.

Such were the circumstances of my illness, caused by the experimental inoculation against typhus, the efforts that my colleagues undertook to save my life, and my convalescence in the harsh realities of the prisoners’ hospital in Auschwitz.

***

Translated from original article: Głogowski, Leon. “Królik doświadczalny.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1965.

Notes

- Schreibstube, German for “office.”a

- “Canada” was a storehouse of goods confiscated from new prisoners on arrival. It was located at a distance from the main camp.b

- Stehbunker (German)—confinement in a cell where the prisoner had to be up on his feet all the time.b

- Lagerarzt (German)—SS physician in a German concentration camp.a

- SS-Untersturmführer Herbert Wuttke (1905-?) medical practitioner on the staff of Auschwitz; set up Hospital Block 28. The surname is misspelled in the original article.a See: https://truthaboutcamps.eu/th/form/r5432033284682,WUTTKE.html; https://www.auschwitz.org/muzeum/o-dostepnych-danych/dokumenty-medyczne/haeftlings-krankenbau-auschwitz-i-block-28/..

- Dr Friedrich Entress (1914–1947), SS chief physician of Gross-Rosen in 1941. Later served in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Pioneer of the phenol jab method of killing prisoners. Sentenced to death by the American military court and hanged on 28 May 1947.a

- Lagerälteste, “camp Senior” (German), a functionary in a German concentration camp placed directly under the camp commandant and expected to implement his orders to ensure that the camp's daily routines ran smoothly and that regulations were followed.a Cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapo.

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Marta Kapera, the translator of the article.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

The contents of this site reflect the views held by the authors and do not constitute the official position of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.