Author

Stefan Kasperek, MD, PhD, b. 1932, neurologist, neuropathologist, and medical educator, co-organizer of the Solidarity Union in Upper Silesia, 1980–1981. In 1991 received the scientific prize of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Poland for his scholarly achievement.

(Affiliation: Klinika Neurologiczna Śląskiej AM w Zabrzu;1 Head: Dr S. Żebrowski)

One of the consequences of Nazi Germany’s racial criteria and the principle that some nations were biologically superior to other nations was its special, well-nigh Utopian concern for the biological perfection of the German nation. Germany put these ideas into practice in a wide-ranging programme of state intervention in population processes. Germany conducted both a “positive” population policy (for instance, the Lebensborn2 operation), as well as its “negative” counterpart. At first, the “negative” policy meant the mass sterilisation of individuals deemed “unsuitable” for procreation on purportedly scientific eugenic grounds, and eventually their mass murder.

The decision-makers of the Third Reich intended to implement a sinister plan to prevent the biological reproduction of whole communities or segments of the population which for utilitarian, economic, or simply practical reasons were not shortlisted for immediate extinction. In this case, the preventive measure was to be mass sterilisation.

Germany only managed to start this programme, which was at odds with civilised conduct and hostile to human nature. Nonetheless, there was enough time for German scientists like the gynaecologist Carl Clauberg,3 the medical practitioner Horst Schumann4 and other German physicians to invent a technique and design all the details required for the mass sterilisation of women, and the X-ray castration of men and women (See References 6, 8, and 9). The criminal experiments they carried out to develop the project cost the lives of thousands of prisoners in Auschwitz.

On the other hand, Germany managed to put into practice other methods of Clauberg’s “negative demography” on a wider scale. It implemented its plan to exterminate the Jewish people and large groups of Roma people, Poles, and Russians. Under the guise of its “euthanasia” programme practised in hospitals and secret centres specially established for the purpose, German doctors (including university professors) and health workers simply murdered the mentally ill, children with growth disorders and intellectual disabilities (Reference 8). These crimes constitute the most infamous chapter in the history of medicine. The legal proceedings against these criminals and the publicity they generated have made world opinion generally aware of the extent of their extermination projects and the circumstances in which they were committed in particular phases of the War.

The enormity of death and suffering Nazi German doctors inflicted on defenceless victims, both healthy as well as disabled or sick individuals, is still drawing our attention and making us wonder what led to those most heinous fascist crimes. What were the stages that preceded the atrocities committed in the field of medicine and population control? Chronologically, the first step was the law “on the prevention of hereditarily diseased offspring” (das Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), which was entered in the German statute book on 14 July 1933, less than six months after Hitler came to power.

Interest in eugenics was widespread in Europe in the 1920s and ‘30s, and resonated particularly with the Nazi Party.5 The Kaiser Wilhelm Institut für Anthropologie, menschliche Erblehre und Eugenik (the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, the Science of Human Heredity and Eugenics) was founded in Berlin in 1927, and in July 1932 the Health Council of Prussia put forward a proposal for the institution of voluntary sterilisation on eugenic grounds. At the same meeting, the notorious Dr Conti, representing the Nazi Party and later one of the key figures in the Nazi German health service, called for mandatory sterilisation on racial grounds (Reference 12). The draft bill for the sterilisation law was ready by the time Hitler came to power, though it prescribed the consent of the interested party (or of his or her legal guardian) as a necessary condition for the operation. The supporters of the bill and the German government argued that analogous legislation was already in force in some states of the USA, Denmark, and the Canton of Vaud in Switzerland.

The Nazi German sterilisation law made forced sterilisation by surgical means legal for “hereditarily diseased” (erbkranke) persons, that is individuals diagnosed with 1) congenital mental deficiency (angeborener Schwachsinn), 2) schizophrenia, 3) maniacal-depressive psychosis (bipolar disorder), 4) hereditary epilepsy (erbliche Fallsucht), 5) Huntington’s disease, 6) hereditary blindness (erbliche Blindheit), 7) hereditary deafness (erbliche Taubheit), and 8) severe hereditary growth disorders (schwere erbliche körperliche Missbildung). Alcoholics made up another group subject to forced sterilisation. On the other hand, sterilisation for social reasons and the sterilisation of healthy members of the family of a “hereditarily diseased” individual were prohibited.

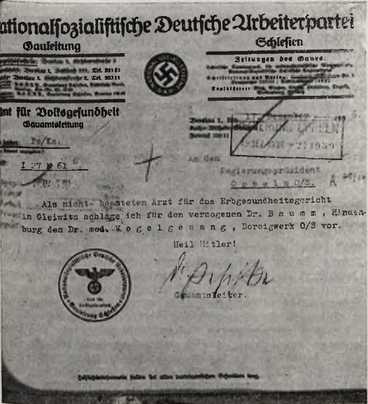

Photo 1. Document issued by a local unit of the Nazi Party in Silesia concerning a doctor’s appointment for service on the judges’ bench of the Court for Hereditary Health Matters (see the text of this article for a commentary). Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1968. Click the image to enlarge.

The sterilisation law comprised 18 paragraphs and came in force on 1 January 1934. It prescribed that the patient himself could apply for sterilisation. Others authorised to apply for the sterilisation of another person were his or her legal guardian, his or her doctor (that is the chief physician for the district); or the head of the welfare institution of which the patient was a resident. Physicians employed in prisons, concentration camps, and army, police, or SS units held the same right to apply for the sterilisation of “patients” in their “care.” Persons providing medical treatment and care were legally bound to report “hereditarily diseased” patients and alcoholics to the district physician. Applications submitted by a doctor—it was enough for them to be signed by just one doctor, regardless of his specialist field—were reviewed and endorsed by the Erbgesundheitgericht, the “Court for Hereditary Health Matters.” There were 205 of these special courts throughout Germany (Reference 12), and three magistrates served on the bench: the judge (a legal specialist) and two doctors, one as the “official” physician (but not the doctor who had submitted the application), and a second doctor, who was “familiar with matters pertaining to hereditary health” (as postulated but not actually required by the sterilisation law). Only “Aryan” physicians had the right to hear cases in a hereditary health court, and were required to keep strictly to the letter of the sterilisation law. Decisions and expert opinions on prospective candidates for appointment to such a “hereditary health” bench were made by, or on consultation with, the Nazi Party (Photo 1).

The court issued a summons on the person named in the application to attend the hearing, and if need be subpoenaed him or her. The court could call witnesses and experts, but had the right to make a discretionary decision on the evidence they provided. Verdicts were passed by a majority vote, and in most cases the court issued its approval for the sterilisation (Reference 11). Appeals were heard by Erbgesundheitsobergerichte, special appellate courts for hereditary health in the 26 Oberlandesgerichte (regional appeal courts). Distinguished psychiatrists served on the bench of these courts of appeal. For instance, Prof. Ernst Kretschmer, who established a human typology, officiated in the court of appeal in Kassel; his colleagues Prof. Karl Bonhöffer and Prof. Johannes Lange, head of a neuropsychiatric clinic, played an analogous role in Berlin and Breslau respectively (Reference 12).

According to an instruction issued by the Minister of Justice, first instance courts could hear 15–20 sterilisation cases in a sitting, and courts of appeal could handle 12–15 cases in a sitting (!).

Sentences were carried out only by authorised physicians in the hospital designated for the given area. Under §12 of the sterilisation law, sterilisations were to be conducted even against the wishes of the person concerned, and the police could be called in for physical enforcement (unmittelbarer Zwang). The only way to pre-empt the carrying out of a final judgement was to have the person concerned confined indefinitely in a secure institution with absolutely no access to members of the opposite sex. Concentration camps were considered “secure institutions,” but monasteries and the welfare homes run by monasteries were not. The minimum age for legal sterilisation was 10, but forcible sterilisation could not be performed on children under 14. Initially, surgeons could choose the method they used for an operation. However, there were cases where the surgery failed, so later the recommended procedure was the vasectomy of at least 5 cm on each vas deferens for male sterilisation. In 1938, the X-ray and radium sterilisation of women over 38 became legal, providing the woman or her guardian consented.

The Nazi German sterilisation law which I have summarised was put into widescale practice by means of a series of executive ordinances. The aim of the ordinance of 31 August 1939 was to limit sterilisation only to those cases where there was “a particularly high risk of procreation.” The right to submit applications for sterilisation was withdrawn in September 1944. Significantly, the time when a limit was put on the sterilisation project—no doubt mainly because of the imminent outbreak of the War—coincided with the commencement of preparations to bring in “euthanasia” for the mentally ill. At any rate, there is ample evidence to prove that against the backdrop of legal forced sterilisation for Ballastexistenzen (persons considered an economic burden to the State), Nazi German eugenicists and “improvers” of humankind had already started to design a Gnadentod (mercy killing) project for them much earlier (Reference 8). For instance, in the archives of Merseburg in the German Democratic Republic, I came across the minutes of a meeting held in Münster in August 1933 and entitled Debatte über Sterilisierung und Euthanasie (A debate on sterilisation and euthanasia). One of its participants, Prof. Tischleder6 of the Faculty of Catholic Theology at Münster University, had to remind the rest of its attendees of matters which seem so self-evident. He said that “the State had the authority to take the lives of criminals, but not of the innocent,” and that “spiritual and ethical imponderabilia take precedence over perfunctory calculations. . . . If we acted only on the basis of the principles of eugenics, many of the world’s spiritual giants who were not paragons of physical perfection would have been denied the right to live. . . .”

Notwithstanding opposition in German society and protests and criticism from a variety of points of view expressed abroad (References 3, 4, 5, and 7), the authorities of Nazi Germany legalised and staunchly implemented forced sterilisation. In violation of the individual’s personal liberty and full of contempt for the disabled and human dignity in general, the project undoubtedly created the right atmosphere for a far more nefarious crime. Nazi Germany moved on to the mass implementation of so-called “euthanasia,” for which there were no legal grounds at all, merely a confidential instruction Hitler issued in the autumn of 1939 (References 8 and 10).7

The question of how the Nazi German sterilisation law was carried out calls for a separate study, which would exceed the bounds of this article. Here I shall limit myself to a look at how it worked in Bytom and its powiat, which was part of Regierungsbezirk [Administrative Region] Oppeln8 at the time. This study is based on the original German administrative records now preserved in the Polish State archives kept in the Wrocław and Katowice voivodeship archives. A full discussion of all the records for the region of Opole and Lower Silesia would call for a much larger presentation.

An Erbgesundheitsgericht was established for the municipal court (Amtsgericht) at Bytom (and likewise, another was set up for Gliwice). The doctors who served on the bench in Bytom were as follows: officially appointed physicians—Dr Fabisch (a neurologist and court expert), Dr Andreas Fox, and Dr Jürgens (the district physician for the powiat of Zabrze9); physicians not officially appointed—Dr Stridde, Dr Wiesner (district physician for Strzelce Opolskie10), Dr Scholz, and later Dr Lemmel. Usually, proceedings were initiated by the Gesundheitsamt (the counterpart of a municipal health department). Dr Fox was the head of this department, and Dr Ebert was its deputy head. These two names appear on several of the extant records for the inquiry [at the start of proceedings], entailing the patient’s detailed personal interview (and especially his/her family interview), a medical opinion on his/her physical and mental state of health, a diagnosis and its grounds, concluded with an application for sterilisation. For cases of “congenital mental deficiency” there was also an Intelligenzprüfungsbogen (intelligence test form) which had to be completed. This form contained a large number of printed questions including arithmetic tests and fairly difficult mathematical problems which the patient was required to solve, as well as answer questions on Martin Luther, who discovered America etc. Persons shortlisted by health workers, administrative officers, and especially by social welfare institutions were called to appear for the inquiry and tests.11 A health department nurse carried out the interview at the patient’s home address and compiled a detailed family tree. However, applications for sterilisation were submitted only for those members of the patient’s family with a distinctly pathological phenotype. Those who looked healthy were not subject to the sterilisation law, even though (presumably) according to the officially approved Mendelian laws of inheritance, they would have carried the “diseased” trait(s) in their genotype.

The court’s task was to hold an in camera hearing to determine whether there were good grounds for the official physician’s application for a sterilisation. It questioned the “hereditarily diseased” person. Only in a handful of cases were such individuals sent for observation to the psychiatric hospitals at Toszek or Branice,12 or one of the clinics in Wrocław.13 Appeals against decisions handed down by the Bytom court were heard by the Erbgesundheitsobergericht in Wrocław using the records for the proceedings without hearing the person subject to the decision. Under the provisions, the operation was to be conducted within 14 days of the final judgement.

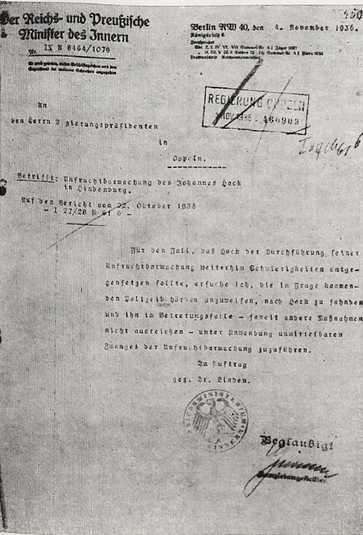

Photo 2. Letter issued by the Reich Ministry of the Interior ordering the forcible sterilisation of J. Hoch. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1968. Click the image to enlarge.

Each stage of the proceedings was accompanied by police enforcement, that is the patient was brought in and appeared under a police escort (see Table III). Usually, a police escort was needed when the patient had to be sent to the hospital. We have an abundant surviving collection of letters exchanged between specific police stations and the institutions involved, including the Reich Ministry of the Interior, concerning particular individuals (Photo 2). To evade sterilisation, such individuals attempted to hide from the German authorities and went as far as to cross the border into the Polish part of Silesia.14 The German police rounded up those who decided to return home and sent them straight to the operating table.

Most of the women from the area of Bytom who were sterilised had the operation performed in the Landesfrauenklinik (District Women’s Clinic; now Instytut Onkologii [the Oncological Institute]) at Gliwice.15 In the first 18 months of the programme, 478 women from various parts of the Opole region of Silesia were sterilised in this hospital by Dr Scheffzek and Dr Nieslony. Table II presents the data for the sterilisation of inhabitants of the city of Bytom and its powiat (Bobrek-Karb, Miechowice, Miedary, Mikulczyce, Rokitnica, Stolarzowice, Szombierki, Wieszowa, and Zbrosławice). These are not the full figures and only cover the period up to mid-1938. The figures for the subsequent period have not been retrieved.

| Hospital | Authorised physicians | Number of sterilisations to 30 June 1935 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sterilisation | |||

| 1 | Bytom Municipal Hospital (now No. 1 Municipal Hospital in Bytom) | Max Wülfing | 135 |

| 2 | Bytom Miners’ Association Hospital (now No. 2 Municipal Hospital in Bytom) | Johannes Becker, Peter Amende, Ernst Undeutsch | 12 |

| 3 | Rokitnica Miners’ Association Hospital (now a unit of the Silesian Medical Academy) | Arch. Clifford, Kulczynski | 4 |

| Female sterilisation | |||

| 4 | Women’s Clinic at the Miners’ Association Hospital now No. 2 Municipal Hospital in Bytom) | Baum, Schmidt | No data |

Table I. Hospitals designated to conduct surgical sterilisation

If we recall that the region’s population was just under 200 thousand, a figure of 616 sterilisations in four and a half years shows the intensity and speed with which the project was carried out. The 1959 edition of the Encyclopedia Americana16 says that 56,139 eugenic sterilisations were performed in 33 states of the USA in the period from 1907 to 1953; and only 190 such operations were done in Denmark in 1929-1934 (Reference 11).17

The incomplete statistics for Bytom presented in Table II show that the largest number of sterilisations were cases of “mental deficiency;” schizophrenics probably accounted for the second largest group; and epileptics made up the third largest group. A critique of these eugenic doings would exceed the bounds of this article. The data for Bytom suggests that psychiatric conditions, along with oligophrenia (congenital dementia), must have accounted for the overwhelming majority of recommendations for sterilisation under the Nazi German sterilisation law. Tadeusz Bilikiewicz18 gives the following critical review of legislation for legal sterilisation on these grounds:

Legislation which makes sterilisation legal on the grounds of Mendel’s laws is based on erroneous principles, does not achieve its purpose, and only brings harm to the individuals sterilised pursuant to it. . . . Congenital disorders are observed to pass down mainly by means of lateral (horizontal) gene transfer, in other words through the genotype. It would be practically impossible to identify and neutralise these genotypes, and if a madman who wanted to do it ever came to power, he would have to sterilise at least one-sixth of the population in every country. A preventive project carried out on such a preposterous scale would mean depriving many talented individuals of the right to life. For genius and madness most certainly go hand-in-hand. (Reference 1)

Of all the alarming facts concerning the Nazi German practice of eugenic sterilisation, the following deserve special notice:

- Gütt, a doctor of medicine at the German Ministry of Internal Affairs; Rüdin, a professor of psychiatry in Munich; and Ruttke, a lawyer from the Reich Ministry of the Interior, wrote a commentary on the sterilisation law intended as a kind of handbook for all involved in its implementation, and gave the following definition of “congenital mental deficiency”: “any degree of mental deficiency (Geistesschwäche) which can be medically diagnosed as abnormal, in other words, starting from cases of idiotism through a broad range of imbecility and its variants, down to moronism.” They continued with the following: “The legislator’s intention is to waive sterilisation only in cases where the cause of mental deficiency may definitelybe proved to be exogenous (emphasis in the original text—S.K.). The court for hereditary health has the discretion to decide whether the proof that an external harmful factor was at play has been conducted rigorously or not.” Apparently, there were 300-600 thousand individuals in Germany with “congenital mental deficiency,” and according to these authors, two-thirds of them were due to inherited factors. In reality, Bilikiewicz observes, “treating oligophrenia as a nosological entity is inadmissible, because the overwhelming majority of these cases are due to acquired causes.”

- What Gütt, Rüdin, and Ruttke meant by “hereditary epilepsy” was epilepsia genuina(“genuine epilepsy”) and recommended such a diagnosis whenever no acquired brain damage was observed. The Nazi German eugenicists should be charged not only with holding fallacious, currently anachronistic opinions on epilepsy as a hereditary disease (Reference 2), for which there is no confirmation in the observed facts (Reference 1); they should also be held culpable for recommending diagnoses of cryptogenic epilepsy without insisting in each and every case on a detailed clinical examination, which could well have changed the medical diagnosis reached by the physicians working for the court in an official and unofficial capacity. After all, they were not required to be fully conversant with neuropathology. Not surprisingly, these “experts” armed with arguments put forward by university-educated Party officials did not pay sufficient attention to the patient’s interview, and even ignored the evidence produced by his or her doctor on the diseases he or she had contracted which could have suggested meningitis (Reference 13). Moreover, the diagnoses of erbliche Fallsucht(hereditary epilepsy) made by the Wrocław clinic and other medical centres for those few cases actually submitted to hospital observation as a rule were not based on test procedures already available at the time, such as pneumoencephalography. Extremely moving yet futile pleas for “clemency” sent to Hitler and a variety of other institutions by epileptics and their families have survived and illustrate the enormous harm done to these people, who were put to an additional mutilation.

| Year | Mental deficiency | Schizophrenia | Cyclothymia | Epilepsy | Huntington’s disease | Blindness | Deafness | Growth disorders | Alcoholism | TOTAL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | men | women | |

| 1934 Bytom (city & powiat) | 42 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 1 | 2 | 19 | 9 | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | — | 1 | — | 2 | — | 89 | 59 |

| 1935 Bytom (city) | (48) | (20) | (—) | (22) | (—) | (—) | (7) | (9) | (2) | 63 | 51 | |||||||||

| 1935 Bytom (powiat) | (44) | (18) | (—) | (8) | (—) | (—) | (2) | (—) | (—) | 53 | 39 | |||||||||

| 1936 Bytom (city) | 12 | 14 | 7 | 4 | — | — | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | — | 3 | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | 26 | 21 |

| 1936 Bytom (powiat) | 16 | 17 | 9 | 3 | — | — | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | — | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 35 | 24 |

| 1937 Bytom (city) | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | — | — | 1 | 2 | — | — | 1 | — | 3 | 2 | — | — | — | 1 | 23 | 17 |

| 1937 Bytom (powiat) | 34 | 22 | 4 | 5 | — | — | 5 | 3 | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 43 | 32 |

| 1st half of 1936, Bytom city | No data | 5 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1st half of 1936, Bytom powiat | 13 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 116 | 87 | 48 | 38 | 1 | 2 | 31 | 16 | — | — | 2 | 2 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 350 | 266 |

Table II. Distribution of sterilisations conducted in Bytom from 1 January 1934 to 30 June 1938, by diagnosis

Coming now19 to a discussion of the sterilisation project as it was carried out on the Polish population, it has to be said that the Nazi German sterilisation law applied to all the inhabitants of Germany regardless of citizenship or nationality. As regards foreign citizens (and in the Opole region this meant chiefly citizens of Poland and Czechoslovakia), the German authorities did not enforce sterilisation and the foreign ministry insisted on discretion. However, the rest of the law and the procedures were still applicable. Foreign citizens sentenced to sterilisation had a choice of either submitting to the operation, permanent residence in a secure institution, or leaving Germany. Those who were already in a secure institution and decided to emigrate had to be attended by a police escort right up to the German border. In many cases, they were handed over to the Polish authorities at the border crossing point at Bytom railway station.

Poles who held German citizenship reacted to the sterilisation law in private with as much resistance and apprehension as the majority of German society. When the first summonses for sterilisation started to be served on Polish individuals in Bytom, the Board of District 1 of Związek Polaków w Niemczech (the Union of Poles in Germany), which had its headquarters in Opole, embarked on a campaign to defend them. There were grounds to expect a degree of success, because the Polish community was officially regarded as a national minority and as such held minority rights legally protected under the Geneva Convention in force until July 1937. One of its provisions said that the German State bound itself to grant members of the Polish minority full protection of their life and personal liberty. The Union referred to the Geneva Convention as the grounds for complaints on behalf of numerous individuals to an international body known as the Mixed Commission:

Since surgery to sterilise an individual is undeniably a serious impairment of that individual’s body and deprives him or her of one of the major purposes of life, that is propagation of the species, therefore each and every case of the application of such surgery on members of the Polish minority is a violation of the provisions of the Geneva Convention.

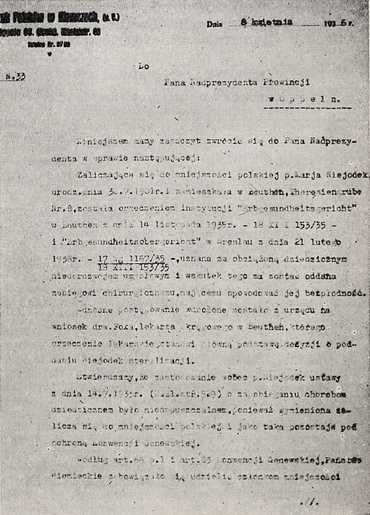

Photo 3. Letter sent by the Union of Poles in Germany protesting against the sterilisation of Maria Niejodek, a Polish woman from Bytom. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1968. Click the image to enlarge.

The complaints also protested against intelligence tests being carried out in German on Polish nationals, whose command of German could well have been insufficient to give a true gauge of their intellectual capacity (Photo 3). It is hard to say whether this was a well-grounded and justified claim. The German records I have examined contain remarks which show that the doctors and courts availed themselves of the services of translators and interpreters. However, there is no doubt that the conditions in which the tests were carried out did not help to make the results objective. We should also consider further circumstances, such as the atmosphere of Prussian courts and administrative offices, which the individual had been trained from early childhood not only to respect but also to fear. Then there was the very subject of the interview and its potential outcome, the menace of an imminent operation perhaps leading to impotence or disability; the individual’s feeling that he or she was being forcibly subjected to a violent measure and did not know how to defend him- or herself against it; the potential presence of an interpreter, not a doctor but a person who was not a professional, not properly trained etc.

The doctor or interpreter would read out the questions in the test from a form, on Luther, Bismarck, Hindenburg, and the difference between a Staatsanwalt (a German state prosecutor) and a Rechtsanwalt (a German attorney or solicitor), or perhaps telling the Polish boy or girl to explain the meaning of German proverbs like Unrecht Gut gedeiht nicht.20 And usually it had all been preceded by the victim being brought in under a police escort, which was humiliating and made him or her feel nervous, apprehensive, and being treated like a laughing stock. The odds were deliberately set against the victim. Dr Fox, Bytom’s most active promoter and executor of the Nazi German sterilisation law, declared in one of the official documents that he did not know a word of Polish.

18 out of the total number of 32 complaints lodged by the Union from the Opole region of Silesia were for Bytom.21 16 concerned cases of oligophrena, and 2 were for schizophrenia cases. Only one case, concerning Stefan Krawczyk of Bytom, was reviewed by the Mixed Commission, which had a branch in Katowice. On 26 July 1936 Mr Calonder, the commission’s president, issued a decision dismissing the Polish complaint. The Commission treated this decision as a precedence and followed suit in all the remaining cases, as well as in two cases concerning Jewish people. The sterilisations of these persons, which had been suspended, now went ahead.

The number of Poles who were sterilised was of course much higher than just the number of complaints submitted to the mixed commission. After the failure of its complaints, the Union of Poles in Germany stopped bringing new cases to the attention of the Mixed Commission and gave up its plan to appeal to the Council of the League of Nations. In the light of the German records we know of today, such a move would probably have compelled the German authorities to suspend the sterilisation of this group of individuals.

We may expect that most of the data presented in Table III for the number of persons forcibly sterilised concern Polish people. Photo 2 concerns one of the Polish men on whose behalf the Union of Poles in Germany lodged a complaint. The document contains an order issued by the Reich Ministry of the Interior enforcing the man’s sterilisation. There are many similar extant documents.

| Year | Bytom | |

|---|---|---|

| city | powiat | |

| 1934 | 70 | < |

| 1935 | 67 | 40 |

| 1936 | 10 | 18 |

| 1937 | 8 | 28 |

| 1938 | No data | No data |

| Total | 155 | 134 |

Table III. Number of forcibly sterilised persons

A comparison of Tables II and III shows that of the 575 sterilisations performed in 1934-1937, 289—over half—were carried out forcibly under a police escort. The fact that in four and a half years only 11 individuals actually requested eugenic sterilisation for themselves, and only two with sterilisation verdicts chose to spend the rest of their lives in a secure institution instead of being sterilised shows why the procedure was so “popular” with German society.

These are figures which the Germans themselves put on record in their reports, and there is no reason to believe that they are exaggerated. Moreover, many patients, finding themselves in a variety of situations, decided to go to the hospital and avoid being escorted by the police. They were some of the first victims of Germany’s “inhuman medicine.”

The same hands which only “mutilated” them later turned to killing millions of people, including distinguished individuals, nonetheless those hands carried the bloodstains of those weaker humans as well.

As time went on, the German police had less trouble with these victims putting up resistance. This fact shows that opposition waned as the machinery of the Nazi German State gained a firmer grip, and German society capitulated when challenged by the onslaught of racist propaganda with its intimidating vision of degeneracy and the gigantically puffed up bill society would have to pay to maintain the disabled.

***

Translated from original article: Kasperek, Stefan. “Sterylizacje ze wskazań eugenicznych w latach 1934–1944 na Śląsku Opolskim.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1968.

Notes

- The Neurology Clinic of the Silesian Academy of Medicine at Zabrze; current English name: Department of Neurology at the Medical University of Silesia (Zabrze Branch).a

- Lebensborn was a Nazi institution dedicated to the “improvement” of the German population by promoting a rising “Aryan” birth rate among German women. Its other activities included the abduction of over 200 thousand Polish children deemed to have “Aryan” features (blue-eyed blonds), to be brought up in German families. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lebensborn.a

- For two recent contributions to the research on Carl Clauberg, see Hans-Joachim Lang, “Carl Clauberg’s forced sterilizations in Auschwitz. New findings from little-noticed original documents on the human experiments conducted in Block 10,” and Knut W. Ruyrer, “Prosecuting evil: the case of Carl Clauberg. The mindset of a perpetrator and the reluctance or procrastination of the judiciary in Germany (1955-1957),” p. 67-78 and p. 79-102 respectively in Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire, Conference Proceedings 2022, Kraków: Polish Institute for Evidence Based Medicine, 2022. See also Czesław Głowacki, “Records of Carl Clauberg’s criminal experiments,” the online English edition of Głowacki’s original Polish article “Z dokumentacji zbrodniczych doświadczeń Carla Clauberga” (Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1976), on this website.a

- For Horst Schumann, see “X-ray ‘sterilisation’ and castration: Dr Horst Schumann,” the online English version of Stanisław Kłodziński’s original article, “Z zagadnień ludobójstwa. „Sterylizacja“ i kastracja promieniami Roentgena w obozie oświęcimskim. Dr Horst Schumann.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1964), on this website.a

- A eugenics movement also emerged in the same period and developed in the USA.b

- Peter Tischleder (1891–1947), Roman Catholic priest and professor of theology at the Universities of Münster and Mainz. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Tischleder.a

- On 18 August 1939, on the grounds of s secret degree issued by the Reich Ministry for the Interior, Germany started the children’s euthanasia program. Next, Hitler issued another secret document antedated to 1 September 1939, in which he authorized Philipp Bouhler and his private physician Karl Brandt to “exercise their discretion to pass on their powers to other physicians designated by name, to exercise the right to the mercy killing of patients declared incurably sick in accordance with human knowledge and following a detailed medical examination.” This marked the beginning of the euthanasia programme codenamed T4. T4 was officially suspended in late August 1941, but “euthanasia” continued to be practised surreptitiously.b

- In his article Kasperek used Polish names for places and administrative areas which were allocated to Poland at the Teheran, Yalta, and Potsdam Conferences at the end of the Second World War, but previously belonged to the Third German Reich. The German name for the City of Bytom was Beuthen. “Powiat” is the Polish term conventionally used to translate the German term “Kreis” or “Landkreis.” In line with our translation policy of faithfulness to the original text, we have kept the article’s original version of these place names, i.e., usually their Polish names, even though from the point of view of historical accuracy, most of these places belonged to Germany prior to 1945.a

- The German name for this city and district (which does not appear in Kasperek’s article) was Kreis Hindenburg (until 1926).a

- The German name for this city was Gross Strehlitz.a

- An interesting document dated 8 June 1938 has survived, reminding Dr Seiffert, the head of the Bytom home for the disabled (now Centralny Szpital Górniczy [the Central Hospital for Miners]) of his duty to submit applications for sterilisation. The fact that this doctor, who had hundreds of disabled persons and patients in his care, was only entering their names on the official register (which it was his duty to do), but not submitting applications for their sterilisation (which he had the authority to do) seems to indicate his opinion of the sterilisation law. According to an oral statement made by J. Kwietniewski in the light of his knowledge of Dr Seiffert’s conduct, unlike many of his colleagues in the city, Dr Seiffert made a purposeful decision not to join in the sterilisation campaign.c

- German names prior to 1945: Tost and Branitz respectively.a

- German name: Breslau.a

- The names of persons who were evading the sterilisation law by going into hiding were published in Deutsches Kriminalpolizeiblatt, a police circular with the names of persons on the wanted list.c

- German name: Gleiwitz.a

- The name is misspelled in the Polish text.a

- About 11 thousand eugenic sterilisations are estimated to have been performed in Denmark in 1929-1967. See Denmark—Around the World—Eugenics Archives online, accessed October 2022.b

- Tadeusz Bilikiewicz (1901-1980), Polish psychiatrist, historian of medicine, and professor of psychiatry. During the War saved lives by harbouring Jewish and Polish people in his hospital. https://khm.cm-uj.krakow.pl/sylwetki-historykow-medycyny/tadeusz-bilikiewicz/.a

- Kamila Uzarczyk writes that Wilhelm Frick, Reichsminister of the Interior, issued a confidential document dated 9 May 1934 and addressed to the diverse Regierungsbezirke with the guidelines for the treatment of foreign citizens in connection with the sterilization law. It said that the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring was applicable to foreign nationals resident on German territory but stressed that all such individuals could evade sterilization by immediately leaving Germany. The German authorities intended to revoke the residence permits of those foreigners who neither left the country nor submitted to sterilization. As of 1 June 1934 Germany brought in deportation as the ultimate sanction on such individuals. (Kamila Uzarczyk, Podstawy ideologiczne higieny ras i ich realizacja na przykładzie Śląska w latach 1924-1944, Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2002, p.271-273).b

- Literally “Evil never prospers.” Cf. the English proverb “Ill-gotten goods never thrive.”a

- This is the figure given in the records of the Minderheitsamt (Office for Minority Affairs) in Opole. Wojewódzkie Archiwum Państwowe, Wrocław.c

- Online English translation on this website: “X-ray ‘sterilisation’ and castration in Auschwitz: Dr Horst Schumann.”a

- English editions: English editions: Doctors of Infamy: The Story of the Nazi Medical Crimes. (First Edition: New York: Henry Schuman, 1949); and The Death Doctors (First Edition: London: Elek Books, 1962).a

- German name: Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz; currently known in English as the Secret State Archives Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (or alternatively the Prussian Privy State Archives) and preserved in Berlin-Dahlem. During the Second World War, some of its collections were moved to Merseburg, which after the War was in the Soviet zone of occupation and subsequently in East Germany, where Stefan Kasperek could access it. After German reunification, the Merseburg collections were sent back to Berlin. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussian_Privy_State_Archives.a

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Katarzyna du Vall, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; c—original footnotes, retained after the original.

References

- Bilikiewicz, Tadeusz. 1966 (Third edition). Psychiatria kliniczna. Warszawa: PZWL.

- Dowżenko, Anatol, and Zdzisław Huber. 1960. “Zagadnienie dziedziczności w padaczce.” Neurologia, Neurochirurgia i Psychiatria Polska10: 639-649.

- Hanke, E. 1937. “Stanowisko medycyny i Kościoła wobec sterylizacji.” Gazeta Lekarska Śląska Polskiego 2.

- Hirszfeldowa, Hanna. 1936. “Prawa dziedziczności w zastosowaniu do medycyny z uwzględnieniem ustawy sterylizacyjnej.” Warszawskie Czasopismo Lekarskie8.

- Karfiol, Z. 1937. “Krytyczne uwagi do ustawy Rzeszy Niemieckiej w celu zapobieżenia dziedzicznie choremu potomstwu.” Gazeta Lekarska Śląska Polskiego3.

- Kłodziński, Stanisław. 1964. “Z zagadnień ludobójstwa. „Sterylizacja” i kastracja promieniami Röntgena w obozie oświęcimskim.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 105-111.22Online English translation on this website: “Genocide issues: X-ray ‘sterilisation’ and castration in Auschwitz: Dr Horst Schumann.”

- Mikułowski, Włodzimierz. 1936. “O zagadnieniu niemieckiej ustawy sterylizacyjnej.” Warszawskie Czasopismo Lekarskie13: 35-38.

- Mitscherlich, Alexander, and Fred Mielke. 1963. Nieludzka medycyna. Warszawa: PZWL.23

- Sehn, Jan. 1958. “Zbrodnicze eksperymenty Carla Clauberga.” Zeszyty Oświęcimskie2. Wydawnictwo Państwowego Muzeum w Oświęcimiu.

- Sehn, Jan. 1961. “Niektóre aspekty prawne tzw. eksperymentów dokonywanych przez hitlerowskich lekarzy SS w obozach koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 35-44.

- Żółtowski, Henryk. 1935. “Obezpłodnienie w świetle nauk społecznych.” Higiena Psychiczna3/5: 134-154.

- The Former Prussian Secret State Archive;24 currently Deutsches Zentralarchiv, Abt. Merseburg (German Democratic Republic), Rep. 76 - Vc, Nos. 128 and 128a.

- Wojewódzkie Archiwum Państwowe, Wrocław [(Polish) State Archives, Voivodeship of Wrocław]; the following collections: Rejencja Opolska [Regierungsbezirk Oppeln], Ref. Nos. I/13703-13708. Nadprezydium w Opolu [Oberpräsidium Oppeln], Ref. Nos. 819 ff., Urząd dla Spraw Mniejszości w Opolu [Opole Office for Minority Affairs] Ref. No. 597 ff.

- Wojewódzkie Archiwum Państwowe Katowice [(Polish State) Archives, Voivodeship of Katowice]; records of the former Staatliches Gesundheitsamt des Stadt- und Landkreis Beuthen [(German) State Health Office for the Municipal and Rural District of Beuthen].

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

The contents of this site reflect the views held by the authors and do not constitute the official position of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.