Authors

Antoni Kępiński, MD, PhD, 1918–1972, Professor of Psychiatry, Head of the Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Academy of Medicine. Survivor of the Spanish concentration camp Miranda de Ebro.

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English

Auschwitz cannot be simply treated as a matter of the past because—far more frequently than we are ready to admit—it is a reference point for the values we cherish nowadays, and it prompts us to reflect on what is important to us now. Thinking of Auschwitz encourages us to make new observations and new interpretations, especially in sociology, ethics, psychology, and obviously medicine and law. The medical profession is turning its attention to camp experiences more and more to see how it can help not just survivors but also people today. Medical research on the impact of war and camp imprisonment on the health of survivors should not focus only on their suffering, but also on their beneficial reactions.

Camp survivors and even people who know about concentration camp life from second‑hand information often endure nightmares, full of scenes of horror, fear, helplessness, monstrosity, and dismay. They feel harassed by their dismal, grey visions and on waking are relieved the nightmares are over and they can enjoy the sunlight and the natural colours of the day. Camp life was scary and offered neither colours, nor flowers, nor birdsong; and the only animals prisoners could see were the rats or the SS men’s Alsatians.

Prisoners vegetated from one day to another. With their shaven pates and identical, filthy prison gear, they were people turned into numbers, and with time became so emaciated that they were almost indistinguishable. Battered, humiliated, and starved, they pined for a slice of bread or a spoonful of soup. Intimidated and vulnerable, they impassively followed orders and suffered the swearing and the violence. When an individual entered the camp, the old personality had to vanish and so did the habits, aspirations, and everyday concerns. Human individuality was brutally and ruthlessly erased during the mock rituals of admission to the camp, quarantine, coercive “sports,” and stupefying “singing practice.”

Individual differences are typical of all living things; they account for the richness and diversity of life forms as well as for their distinction from inanimate nature or the world of technology, which looks grey and monotonous in comparison with the living world. The evolutionary apogee of individual differences is to be found in humans. Every human being is unique, has their own personal world as well as their own experiences, feelings, and dreams. The concentration camp prisoner was to be deprived of individuality, the feature of all sentient creatures, especially humans. The prisoner was to become a statistic, an automaton with a nondescript face, and obediently carry out the orders of the oppressors.

The immensity of evil that was manifest in the death camps is hard to imagine. Humiliation, physical violence, starvation, slave labour during which many prisoners died, degradation, scabies, typhus, dirt, lice and fleas, dead bodies, cesspits in which some prisoners drowned, abusive language and shouting, the utmost cruelty—all of that left the individual dumbfounded and crushed. The prisoner was transformed into an insensitive, thick‑skinned brute whose only aspiration was to stay warm, avoid being beaten, procure a morsel of food, and snatch a few hours of sleep to regain some of the spent energy.

Prisoners were treated with maximum brutality, especially at the beginning of their imprisonment. The purpose was to obliterate their individuality as quickly as possible. The process can be compared to the work of the roller that was used to compress road surfaces in the camp. Prisoners were to be squashed to form a depersonalised, homogeneous mass of camp numbers. Above all, SS men wanted to destroy human dignity. That was achieved by making prisoners wear ridiculous camp gear; beating and mortifying them; calling them offensive names and swearing at them; forcing them to perform exhausting labour, which would have been hard even for beasts of burden; and forcing people to live in conditions where neither personal hygiene nor any sense of modesty could be maintained.

In the majority of cases the SS men managed to achieve their aims. On the average, within the first few weeks in the camp a prisoner collapsed mentally, becoming a Muselmann and focusing on devising ways to survive just one more day. With the mental strength sapped, the physical health deteriorated: the diminished body of a person who had been starved, bruised, and exhausted with too much strenuous work was more and more prone to succumb to disease and infection of any kind. Common health problems were starvation diarrhoea (called Durchfall in German) and starvation oedema, suppurating skin infections, frostbite, etc.

This critical period decided about a prisoner’s survival. He or she either became a Muselmann, physically and spiritually depleted, and died within the next few months, or managed to find an inner source of strength, the “high castle” of self‑defence which was described by Prof. Stanisław Pigoń in his memoirs of his Sachsenhausen imprisonment (Wspominki z obozu w Sachsenhausen). In one’s castle one successfully defended one’s individuality against the pressures of the infernal camp realities.

In general, prisoners had two options, and the choice was not easy. The first one was to identify with the system of terror and try to scale the ladder of the camp hierarchy as high up as possible, since the higher you climbed it, the less beating you took. Alternatively, the prisoners could strive to preserve the core of their old personality, to protect their most essential humanity, which did not let them slip into degeneration. At this point we have to talk about arguably the most extraordinary phenomena observed in the death camps; quite aptly, one of the women prisoners called them the “heaven” and “hell” of the camp.

A camp was not simply a hell; it could show glimpses of heaven, too. It did unleash hatred, evil, and bestiality, but it also gave many impulses for kindness, benevolence, and nobility in forms not to be witnessed in normal life. A camp prisoner was degraded and humbled, but could still keep their dignity. The situation forced them to look for help in the deepest strata of their own psyche, so as to tap enough courage to withstand the thrust of the evil assailing them. In the hell of the camp, the innermost virtue of human being could crystallise out, because one was capable of survival only by rallying what was most sublime, and only by this means could one defy the reality in the camp.

When survivors have a reunion after the lapse of thirty or so years1, they remember their old days, start using the camp jargon again, and even tell the same old jokes. Their memories do not return to the hardship and horror, but to the “heaven” of the camp, meaning all those important or not so important events which demonstrated that humans can defy evil to evade being crushed by the rollers of death.

It is in this that survivors perceive their own and their fellow‑prisoners’ greatness, the indomitable human spirit. They trust in themselves and their closest friends, those who lived through the camp’s privations. They have passed the most difficult test and did not fail their fellow‑prisoners.

Sometimes we find it hard to pin down the most important traits in a human being, the essence of his or her soul. People put on so many masks that it is a challenge to say who they really are. But the camp environment was so stressful that all the masks peeled off to reveal a person’s true face. That seems to be one of the bonding factors in the survivors’ community.

Upon entering the camp’s hell, one’s immediate, natural reaction was to try to save one’s life regardless of the cost. That was understandable, for life is the highest value for any sentient creature, not only a human. Yet this response could spur egoistic conduct, because one’s own existence tends to appear more precious than that of other people.

In the long run, however, this automatic response proved inadequate. The imperative of safeguarding one’s own life at all costs turned a prisoner into a Muselmann or, if he or she showed more than average cruelty or sneakiness, or simply had more luck, into a member of the camp’s “ruling class.”

In an apparently illogical way, it was the altruistic attitude that brought more long‑term profits. When we listen carefully to survivors’ stories or read their memoirs, we may often find that a vital element of their existence in the camp was their concern for their neighbour.

It transpired in acts of great or small significance; some of them would have been completely irrelevant in ordinary life, but in the camp they could save somebody’s life and faith in human kindness. One of the female survivors remembered another inmate who spent one night washing off the dirt and excrement from the skin of an old Jewess in the Muselmann condition. The poor sick woman died within days, but perhaps before she departed, she enjoyed a glimpse of the heaven of the human heart. Another survivor said she once warmed up a fellow‑prisoner with the heat of her own body, slowly reviving her from severe hypothermia. Many survivors recollect that a gentle word or gesture, a smile or a joke restored their self‑confidence, their trust in their brothers and sisters in adversity, and in the possibility of survival. It is impossible to estimate how many prisoners endangered their own lives in order to protect their fellows when they could have been selected for death, to procure medicine or food for them, or to send an illicit message to the outside world.

A group of “camp aunts,” who evolved into an institution in its own right, included seasoned women prisoners who took care of the younger and inexperienced ones. Many friendships formed in the camp which were unlike any other relationships, with so much mutual devotion and understanding, and readiness to make sacrifices. Most of those friendships survived the camp, provided that neither of the companions died in the meantime.

Apart from spontaneous, individual impulses to help, aid was also provided in a more systematic manner. For instance, functionaries in the Auschwitz camp hospitals put their lives at risk to grab extra vats of soup, more bread portions, and rusks for their famished wards. Particular working teams wangled clothes, towels, and shoes. The Block and Stube functionaries tried to secure more straw mattresses and blankets. Considering the needs, the scale of this aid was negligible, but its psychological value was not to be overestimated in the face of the enormity of evil. Prisoners caught helping others could be punished by being flogged, suspended by the arms on the post, put in the bunker (viz. dungeon), or even shot.

In the direst of situations, prisoners were able to contrive a really unconventional method to rescue a fellow‑inmate. For instance, on 29 August 1942, over ten Auschwitz prisoners were saved from gassing, because a hiding place was found for them in the sewers between the barracks. Oftentimes, the emaciation of many a Muselmann was turned into an asset: it was possible to conceal them under the blankets on the bunk beds to stop the Lagerarzt2 from selecting them for death. Unconscious patients were saved from selection by being buried in piles of dead bodies, or tucked away in large containers and dark corners.

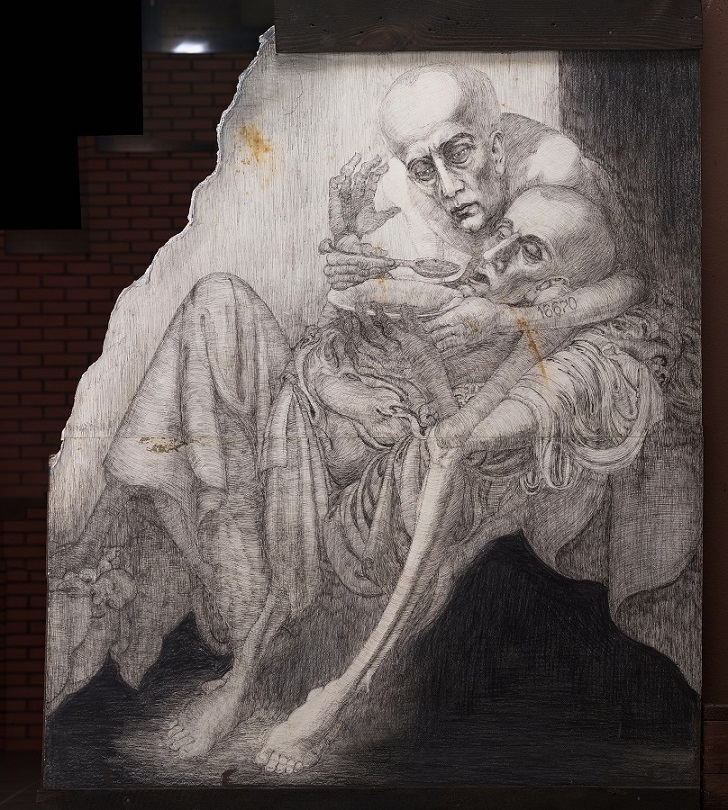

Father Maximilian Kolbe. Marian Kołodziej

Even long imprisonment in the camp did not wipe out the essential human feelings. Veteran prisoners protected new arrivals, who were scared and helpless. For example, they gave away some of their food to complete strangers, saying, “Next month you can do the same for another Muselmann. Come again tomorrow to get some bread.” This extraordinary solidarity saved many lives, as subsistence often literally depended on a crust of bread. It was considered natural for prisoners from the same country or neighbourhood, as well as students of the same school, workers of the same company or members of an organisation to help one another.

Some illicit procedures operated on a large scale. Prisoners obtained food and medicines for the women’s camp and for the sick. From the point of view of an individual prisoner this aid was unsatisfactory and could reach him or her only in very propitious circumstances. Most prisoners survived for about three months and then perished, having received no substantial aid of any kind if no one was able to provide it for them.

Yet whatever was done to help out proves that prisoners did not consider only their particular situation. They truly cared about others too. Perhaps it was this distancing off from the self that made survival possible, even though egoism would have been quite understandable in the hell of the camp. Altruistic attitudes strengthen not only the recipients, but also the donors. Altruism reunites the community of human beings, and the individual is no longer alone in this world.

The longing for togetherness was one of the typical camp phenomena. Prisoners instinctively kept company with those who had previously lived in the same town, served time in the same jail, were working now in the same Kommando or living in the same Block. The huge community of the camp consisted of a multitude of micro‑communities, where mutual bonds gave people more willpower to tough it out.

The modern‑day byword is “alienation.” But concentration camps demonstrated that even in extremely unfavourable conditions an individual is not alone. When they seem to have lost everything, they may still find somebody who is willing to share a bowl of soup, offer a kind word, dispense medicine, do their job for them when they no longer have the strength to do it themselves, or risk their own life to save others from selection. Although nowadays human nature is viewed as permanently flawed, there is such a thing as a truly human community spirit. Homo homini non semper lupus est (The human being is not always wolf to another human being). This profound truth about human heart was revealed in the camps, in extremely tragic and disastrous situations. This is why a concentration camp was not only a hell, but also allowed a glimpse of heaven thanks to the milk of human kindness and favourable attitudes of people who were being harassed and tormented to death.

The topic of the positive aspects of living in a concentration camp is present to some extent in the relevant literature, also in a few academic papers, e.g. by Elżbieta Rosiak. She has described the mental self‑defence mechanisms in Majdanek prisoners, quoting foreign writers, such as Devoto and Frankl, but has regrettably overlooked the articles in Medical Review – Auschwitz3 (some of them by Kraków psychiatrists), which are crucial for a grasp of prisoners’ attitudes and mutual assistance. This problem deserves a special, comprehensive monograph.

It should be noted that Father Maksymilian Kolbe was beatified in the autumn of 1971. He gave his life to save his neighbour. His was a symbolic act of transforming an egoistic attitude into an altruistic one. Father Kolbe has come to stand for all those positive forces that operated in concentration camps and defied all that was inhuman. In Father Kolbe, we celebrate the victory of humanity over bestiality, cruelty, wickedness, and malevolence.

Although Nazi concentration camps were liberated about three decades ago, Father Kolbe’s act is still astonishing the general public today, not only as a historical fact, but also as an ahistorical proof of human worth and fortitude. We should remember also all the other, anonymous people who perhaps did not show such great courage, but after a period of imprisonment in Gestapo jails or in camps gave their lives to protect their fellows. Many of these unsung heroes suffered torture and died only because they did not want to betray their brothers in arms in the resistance movement.

Since they made up a large group, we have even more substantial evidence of the invincibility of the human spirit even in the worst predicament.

Translated from original article: Kępiński A., Kłodziński S.: O dodatniej aktywności psychicznej więźniów. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1973.

Notes

1. The article was originally published in 1973.

2. The chief SS doctor of the camp.

3. Some of those articles have been translated and are available online as part of the Medical Review – Auschwitz project. See especially Chylińska, 1987; Kłodziński, 1975; Gawalewicz, 1967; Ryn, 1986; Kłodziński, 1983..

References

1. Pigoń, S. Z przędziwa pamięci: urywki wspomnień. Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy; 1968.2. Rosiak, E. Niektóre formy samoobrony psychicznej więźniów Majdanka. Zeszyty Majdanka. 1971; 5: 158–173.