Author

Zdzisław Jan Ryn, MD, PhD, born 1938, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and formerly Head of the Department of Social Pathology at the Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków. Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the Kraków Medical Academy (1981–1984). Polish Ambassador to Chile and Bolivia (1991–1996) and Argentina (2007–2008). Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Physical Education (AWF) in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

Let me begin with a personal reflection, really a retrospection. Thirteen years have passed since our last, unforgettable meeting with Professor Antoni Kępiński in Bielsko-Biała. In the town hall’s conference room he presented his Auschwitz-related ideas on the psychopathology of power; they were later published by Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (5). One of the organisers of that conference, held by Polskie Towarzystwo Lekarskie (the Polish Medical Association), was Dr Tadeusz Karolini, a Gusen camp survivor, who is no longer with us.

Professor Kępiński was one of the first advocates of establishing a regular medical care system, including mental health services, for survivors of concentration camps. Somewhat automatically he came to supervise many academic research projects on the effects of the camp trauma. The Psychiatry Clinic of the Kraków University Hospital became the main centre for the treatment of ex-prisoners of Nazi German jails and other places of detention. Within a specially formed, though unofficial section, young doctors took care of this particular group of patients and issued disability certificates to help them obtain social security benefits and compensation, but above all, they were able to conduct medical research. It was my honour to join that team in the early days of my employment in the Clinic.

It was only several years later, after Professor Kępiński died and we were editing some of his vast correspondence, including a collection of letters written during his imprisonment at Miranda de Ebro, a concentration camp in Spain, that I was able to disentangle the secret of his uniquely deep understanding of the experience of camp survivors (10, 11). As it turned out, it was his own, personal experience and ordeal. Probably this is why Kępiński’s studies on concentration camp victims are exemplars of psychological insight.

On the thirty-fifth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz we revised and summed up what medicine knows about the effects of concentration camp trauma. I am going to mine the numerous publications written on the subject, both memoirs and clinical studies, to offer a survey of the most important things we have learned, the things which grasp the essence of the trauma effects. Many of those phenomena have been analysed in the papers that have appeared in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

From a psychiatrist’s point of view, meeting survivors of concentration camps is a unique experience, as it provokes fundamental questions to which we are still seeking answers, namely, what is man and what is his real nature, which is best revealed in extreme situations.

Talking to camp survivors, a psychiatrist discovers a world of unusual experiences spanning an unparalleled range and intensity. To Kępiński and other doctors, they were the strongest impulse behind their decision to delve into this difficult area of study. Stressing the need for developing this discipline, Kępiński wrote,

It was no longer possible to ignore so many problems re-emerging time and again. Those people, who appeared to be just like other people, turned out to be different. Their otherness becomes manifest as soon as they start discussing the camp: agitated, with glowing eyes, they seem to shed all those years that have elapsed since they left the place; suddenly all the events are fresh and recent again, and it is impossible for them to leave the vicious circle of their past; their imprisonment encompassed horror and beauty at the same time, utmost human iniquity alongside kindness and generosity; survivors saw what man is, but in spite of that, or perhaps because of that, they are still puzzled by his nature; maybe they want to find out why so much evil accumulated within the perimeter of the camp and how they managed to resist and live through it. They are sometimes puzzled by themselves. Anyway, much more strongly than any other people, they sense the mystery of man and the elusiveness of social mores, form, and conventions. They see clearly that the emperor is naked. (6)

For the majority of the prisoners, their detention in a concentration camp was infinitely more shocking than any previous experience or trauma. No wonder many of them collapsed under the burden of this reality and died almost as soon as they were thrust into the camp. It was a consequence of the general deterioration of their health, both physical and mental: all their defence mechanisms broke down under the burden of biological and psychological stress.

Those who were able to withstand the onslaught of negative factors and made a heroic decision to persist had to adjust their ways in order to function in the hell of the camp. The choice was tantamount to following a way of indescribable physical and mental suffering. This is why most of the prisoners perceived the realities of the camp as a nightmare, or even a nightmare of a nightmare: they found it impossible to believe the everyday terror was actually going on. Therefore, in many survivors’ memories the distinction between dreaming and staying awake is blurred; while in the camp, they dreamed about their warm family home, and back at home, their dreams were filled with hellish visions of the camp.

How well they could adjust to the camp life depended on a variety of factors, both external and internal (19). What mattered especially in the first days of imprisonment was a sense of belonging to a group as opposed to a lonely and hopeless struggle to survive. This sense of togetherness and being part of a community was crucial in summoning every ounce of strength to tough it out until the end of the day, and so perhaps until liberation. A similarly propitious factor was the activity of the prisoners, whose only future, in the eyes of the SS men, was death (7).

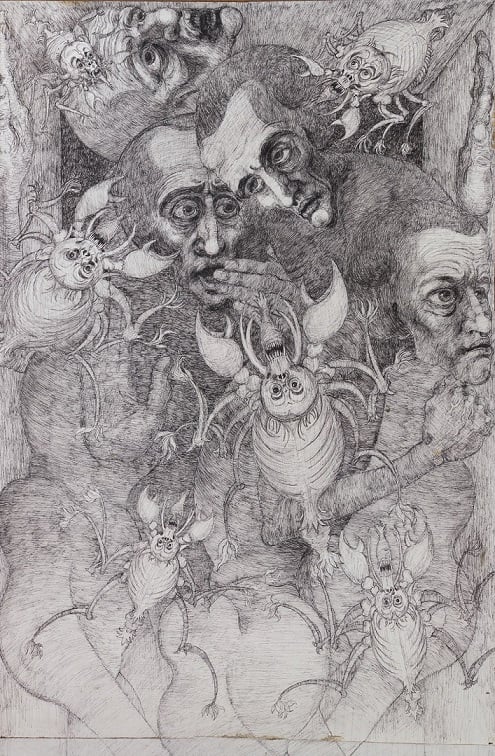

Standing-Room-Only Bunker. Marian Kołodziej

Kępiński writes that an “ordinary act of kindness – which you never notice in normal life, because you treat it as a matter of politeness – when it occurred in the camp, was an absolute revelation, showing a glimpse of heaven, and sometimes saved lives, as it restored people’s faith in the possibility of survival” (6). This means that receiving support from somebody else was also a shock, albeit a positive one. In order to hold out, you had to be unperturbed by whatever was going on, to disengage, to withdraw into your own, “autistic” space. Otherwise, you were killed by the powerful and cruel camp.

Naturally, the prisoners’ most frequent reaction was depression of various shades and severity, which in extreme cases ended in a nervous breakdown, prostration, and physical emaciation paired with a total lack of hope of survival. At that point a detainee became a Muselmann, to put it in the camp jargon. We need to realise that it would be hard to find precedents of such situations in the entire history of mankind. Knowing how frail we are physically and how flimsy our existence is, we can more readily assimilate the fact that in a concentration camp one found it easier to die than to survive.

Those who did survive had never expected that their return to normal life was going to prove so laborious. Once they had been forced to succumb to the camp’s diabolical routines and habits, so now they perceived their environment as immaterial and illusory. What hurt them most was the realisation they were misunderstood and could not establish any meaningful contact with people who did not share their camp experience. This is why they formed survivors’ associations, some of them still in operation, where they were able to meet with kindred spirits.

It would be unimaginable that owing to camp imprisonment and the resulting humiliation of the human body and soul, innumerable injuries and ailments could have had no long-term effects, some of them persisting for a lifetime. Researchers investigating those somatic and mental outcomes come across various obstacles. Their doubts can be presented briefly in a few basic questions: (i) What is the cause and effect link between the injuries sustained in the camp and the present physical and mental well-being of the survivors? (ii) What is the aetiology of some of the disorders observed now, what physical injuries and psychological traumas of the past underlie them? (iii) Is it really so that because of their camp experience survivors are now more prone to somatic sickness, age prematurely, and die sooner than the general population? (iv) Is it possible to establish a causative link between survivors’ camp injuries and traumas and their present-day sickness given the lapse of time?

While discussing the aetiology of camp-induced sickness, causes and effects need to be considered holistically and dynamically. The camp exposed the fact that the human being is an integrated psychosomatic entity: during a prisoner’s detention his entire system had to be ready to fight at any moment, while after his liberation, due to exhaustion, it was beset by systemic sicknesses, a detailed specification of which can only be of theoretical importance.

The protracted and severe camp trauma was bound to leave its permanent mark on the system. Sometimes it remains latent and asymptomatic, and more detailed tests are required to discover it, but often it is brought out into the open by apparently insignificant stimuli. Kępiński wrote,

There are limits to what an individual can take, and you cannot transgress them without a payback. If you do, if you dare to go beyond them, there is no return to your former state. Your fundamental structure has been crushed and you are no longer what you used to be. (6)

Psychiatrists call this phenomenon a “personality change.” It may occur after a traumatic experience, a cranial or cerebral injury, or in an episode of mental illness, such as schizophrenia. Then we talk about negative symptoms or a schizophrenic “defect state.”

Thus, the most frequent mental health symptoms of the old camp trauma are personality disorders. Using non-specialist language to describe personality traits of concentration camp survivors, one can say they are considered irritable, unwilling to make contact with the people around them, distrustful, apathetic, full of anxiety, tearful, unable to see any sense in life, more tolerant of others, prone to come into conflict, indifferent when somebody else is hurt, pessimistic, overcritical of themselves, unafraid to die, preoccupied with their health etc. All these descriptors are listed in an article by Roman Leśniak (8), who discussed personality disorders of survivors in a few dimensions, such as their altered interpersonal attitudes, a changed outlook on life, and the emergence of new, permanent personality traits. On this basis, he distinguished the three most common personality types among survivors, which he dubbed the “downcast,” the “distrustful,” and the “impulsive.”

The most common symptoms are low mood and low life energy, mistrust and suspicion, increased excitability and irritability.

Memories of the camp are vivid with the vast majority of survivors and sometimes grow so intense as to take the form of paroxysmal hypermnesia (9), becoming a reference point for anything that is happening now. They impact on survivors’ relationships with people and their life attitudes, reorganise their hierarchy of values, and tamper with their sensitivity.

It is easy to notice that similar personality changes may follow any other extreme situation in an individual’s life, such as long-term isolation, loneliness, incarceration, or, as I have mentioned, psychosis, especially schizophrenia.

It seems justifiable to conclude that these personality changes, persisting throughout the rest of one’s life, typically occur in the aftermath of events that the individual can neither comprehend nor cope with.

In order to assess the mental condition of survivors up to 30–35 years after liberation, we have to examine their physical health as well. The most obvious somatic problem is premature aging, probably caused by atherosclerosis and other diseases of the circulatory and locomotor system, and the lungs (20, 21), with the incidence of disease double what it is in the general population.

The psychopathology induced by the old camp trauma, which is referred to as Konzentrationslagersyndrom or, for short, KZ-Syndrom in German, and the concentration camp syndrome or the survivor syndrome in English, includes mainly those symptoms that are typically caused by an organic injury of the central nervous system (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18). Their aetiologies differ, as they may have been produced by trauma, contagious diseases, atherosclerotic disease, starvation, or extreme emaciation.

Due to the underlying organic injury of the central nervous system, various psychopathological syndromes develop, dominated chiefly by neurosis, depression, and anxiety; also character traits change due to the organic abnormality. Other diagnoses include encephalopathic syndromes, cerebrasthenia, epilepsy (mainly posttraumatic), paroxysmal hypermnesia, sexual dysfunctions, suicidal tendencies, and neurasthenia.

We offered the survivors in our care regular medical check-ups and follow-up examinations, which turned out to be a prudent decision. Initially two-thirds of the subjects were diagnosed with mental disorders, but the focus of treatment was chronic asthenia or neuroses. However, in later years mental disorders were observed in the majority of the subjects, and the underlying organic causes became more manifest (17).

It should be noted that the clinical presentation of chronic progressive asthenia (or using Targowla’s term, asthenia progressiva gravis), combining various systemic diseases, gradually becomes more and more dominated by disorders of the central nervous system. This is particularly challenging for the medical boards which grant a patient the status of a disabled person who is unfit for work. Although much progress has been made, further effort is needed because a considerable proportion of survivors have not applied to obtain such a status yet; some did not receive the benefit and support they had expected. We could find very many such cases, several of them shocking, in the medical files of the Psychiatric Clinic of the Kraków University Hospital.

To sum up, from a psychiatrist’s point of view the most common aftereffects of concentration camp internment are progressive asthenia and premature aging.

Regardless of their aetiology and presentation, it can be assumed that in all probability there exists a causal link with the concentration camp imprisonment. The most important evidence is as follows: (i) the onset of the illness took place immediately after the patient’s release, it took a fluctuating but persistent course, and the prognosis is poor; (ii) the presentation is specific and homogeneous, incidence is high among the survivors, and the presenting anxiety and compulsions are connected with the camp trauma.

These difficulties are probably the main reason why so far no uniform therapy has been proposed to treat the concentration camp syndrome, although, from the practical point of view, the problem needs to be solved urgently. Hitherto therapies have been devised ad hoc by specialists to whom survivors have been referred, especially those who can understand the survivors all too well, being former concentration camp prisoners themselves. Psychotherapeutic and intuitive skills as well as long-term expertise form the basis of treatment provided to the survivors’ offspring when any pathology shows up.

The Nazi German concentration camps do not exist any more, but their reality lives on in the consciousness and sub-consciousness of the survivors, in their sorrows and anxieties, everyday routines, and nightmares. Even the architects of this deadly network did not anticipate such outcomes. The camps loom large in the minds of former prisoners, and the pain that is still felt after so many years seems to be the cruellest consequence of their internment.

Memories of the camp and the aftereffects of imprisonment in it are to be observed not only in individual survivors’ lives. Recent research unambiguously demonstrates that the post-concentration camp pathology is passed on to the next generation, the children born to and raised by survivors. This is an important social problem, as not only the offspring, but also other family members are affected, such as parents, siblings, widows, and orphans, who continue to make up a considerable proportion of the general population of Poland. Most of the researchers, both Polish (1, 2, 3, 4) and foreign, note the prevalence of personality disorders and neuroses among the survivors’ children. The problems tend to surface during adolescence, sometimes in so severe a form that psychiatric treatment and even hospitalisation is required. Such disorders are considered typical of children affected by inappropriate parenting styles informed by the experience of the camp, a strained atmosphere at home, the aggressive tendencies of the survivors etc.

To finish, I would like to share one more general reflection. In the history of mankind, no tragedies, such as the Second World War and its concentration camps, disappear without a trace. The trauma of war and concentration camp imprisonment has left its indelible mark on our collective memory, which makes us [the people of Poland] different from other nations which were spared such devastating experiences. This could be an interesting thread to follow in psychologically- or sociologically-oriented intercultural research.

When doctors listen carefully to survivors describing their symptoms, when they explore the world of their nightmares and fears and study the aftereffects of the camp trauma in the second and third generation, and finally when they recognise the pain of the social stigma of war, they cannot but realise that the process of healing is going to be prolonged and profound, as it will take many years and many generations to wipe out the negative consequences of the concentration camps, and their effects in so many spheres – biological, psychological, social, moral, and ethical.

Sadly, one cannot exclude the possibility that after several years our descendants may again see some more consequences of the camp trauma. It is so deeply ingrained in the human psyche and mind that we cannot naively believe the corollaries will simply vanish when the survivors pass away.

Translated from the original article: Ryn Z.: Uwagi psychiatryczne o tzw. KZ-syndromie. Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1981.

References

1. Dominik, M., and Teutsch, A. 1978. “Nerwice u potomstwa byłych więźniów obozów hitlerowskich.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 16–20. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/198268,neurosis-in-the-offspring-of-concentration-camp-survivors2. Dominik, M. 1979. “Potomstwo w niektórych rodzinach byłych więźniów hitlerowskich obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 25–33. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/170090,offspring-in-some-families-of-former-prisoners-of-nazi-concentration-camps

3. Kempisty, C. 1973. “Wyniki socjo-medycznych badań potomstwa byłych więźniów obozów hitlerowskich.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 13–20.

4. Kempisty, C. 1979. “Wyniki drugiego etapu socjo-medycznych badań potomstwa byłych więźniów obozów hitlerowskich.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 18–25.

5. Kępiński, A. 1967. “Refleksje oświęcimskie: psychopatologia władzy.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 52–60. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/170061,auschwitz-reflections-the-ramp-the-psychopathology-of-decision

6. Kępiński, A. 1970. “Tzw. „KZ-syndrom.” Próba syntezy.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 18–23. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/170043,the-so-called-kz-syndrome-an-attempt-at-a-synthesis

7. Kępiński, A., and Kłodziński, S. 1973. “O dodatniej aktywności psychicznej więźniów.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 81–84. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/193375,on-the-beneficial-psychological-activity-of-concentration-camp-prisoners

8. Leśniak, R. 1964. “Zmiany osobowości u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim–Brzezinka.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 29–30.

9. Półtawska, W. 1978. “Stany hipermnezji napadowej u byłych więźniów obserwowane po 30 latach.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 20–24. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/170040,paroxysmal-hypermnesia-states-observed-in-former-prisoners-after-30-years

10. Ryn, Z. 1979. “Antoni Kępiński internowany na Węgrzech (1939-1940).” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 85–95.

11. Ryn, Z. 1978. “Antoni Kępiński w Miranda de Ebro.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 95–115.

12. Sobczyk, P. 1980. “Trudności psychiatrycznego orzecznictwa inwalidzkiego odległych skutków działań wojennych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 86–89.

13. Sobczyk, P., Cielecki, A., Zembrzycka-Cielecka, M., Krupka-Matuszczyk, I., Kaźmierczak, B., and Łukoszek, D., “Analiza psychopatologiczna wstępnego materiału orzeczniczego byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 89–91.

14. Sternalski, M. 1978. “Przyczynek do psychiatrycznych aspektów tzw. KZ-syndromu.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 25–27.

15. Szymusik, A. 1964. “Astenia poobozowa u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 23–29. https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/translations/english/170054,progressive-asthenia-in-former-prisoners-of-the-auschwitz-birkenau-concentration-camp

16. Szymusik, A. 1965. “Dotychczasowy stan inwalidzkiego orzecznictwa psychiatrycznego dotyczącego byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 74–75.

17. Szymusik, A. 1974. “Inwalidztwo wojenne byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 110–112.

18. Szymusik, A. 1962. “Poobozowe zaburzenia psychiczne u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu. Doniesienie wstępne.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 98–102.

19. Teutsch, A. 1962. “Próba analizy procesu przystosowania do warunków obozowych osób osadzonych w czasie II wojny światowej w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Doniesienie wstępne.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 90–94.

20. Waltz, R. 1963. “Zmiany chorobowe u byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 41–50.

21. Wojtasik, W. 1974. “Najczęstsze zmiany chorobowe w układzie krążenia u mieszkających na Kielecczyźnie byłych więźniów obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 75–82.