Author

Jadwiga Apostoł-Staniszewska, 1913-1990, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor, No. 26273; survivor of Ravensbrück, Malchow and Leipzig.

Even an unimportant incident can make survivors of Nazi German concentration camps reflect about death. One day after the War when I was visiting the Auschwitz-Birkenau site I saw a flock of pheasants flying away from the barracks towards the fence. They had been frightened and were fleeing. I had startled them. They took a course along the overgrown ditch. For a moment I panicked when I realised they were heading straight for the barbed wire! I calmed down when I remembered that there was no danger, as the barbed wire was no longer electrified and could not kill.

I fixed my gaze on the space between the Birkenau chimneys, now divested of their timber cladding, while my thoughts helped me overcome the barrier of time. Both my sight and my thoughts ran quickly. They soon reached the long brick barracks with tiled roofs, resembling pigpens or stables. Most, or perhaps all of them, have survived, I did not know and did not intend to find out. What surprised me was that their roofs, windows, and narrow doors looked just the same as I remembered them. For a moment, I could not believe that those walls had housed hundreds of female prisoners, or up to a thousand. Could they have shrunk?

From the perspective of time and space, all things look smaller, blurred, reduced to the core truth, to the roots of the reality of those times.

During those dull autumn days, during the spring thaw and during winter, snowflakes merged with soot, and flakes of that grimy mix fell on the Lagerstrasse (camp street); the brick barracks bustled with a strange life, and went numb with an even stranger death. In summer they were surrounded by a grey, scorched, caked and cracked earth, as dry as a shell; not mud-swamped but standing on a lifeless surface, all the time serving their purpose. Now they seemed to be sinking under tall, waist-high grass on a flowery meadow and looked much lower than they had been before.

My recollections helped me revive the barracks and make them appear as they had looked in those days. Inside I rediscovered my old self. The air used to be as thick as tar; it was stuffy and dark. Narrow corridors and burrow-like bunks, packed chock-a-block. Through the overwhelming noise you could hear the harsh yelling: “Quieten down! Stand up! Fall into line!” but you could not catch all the words. Prisoners squeezing through the narrow door, the only way out of the barrack; so close to one another that their bones were creaking. Somewhere at the rear female guards and other functionaries assigned to night watch duty would whack prisoners to get them out quickly for the morning roll call. The door held the crowd back, but did not collapse under the pressure.

Those who are alive had to go out on their own two feet; the dead were wrapped in blankets and carried out last. I did not worry about that; nobody did. We had to line up for the roll call, quickly. We had to stand in rows for an hour or longer before the female SS guard came with a dog, counted the prisoners, gave us a hateful look and said the magic word “stimmt” (It tallies). We had to drink an awful herbal brew, and eat a few cold potatoes boiled in their skins the previous day. Up on our feet, we waited for further orders. To survive we had to be on alert all the time.

The corpses lying in front of the barrack were no concern of ours. The dead do not feel cold, hunger, or fear; neither do they believe – consciously or sub-consciously – in the possibility of survival: they do not count any more. They were only waiting for the last commando – Himmelkommado (commando to heaven). They no longer had to obey any authority. We did – the authority that had created this mass grave for us. And yet… yet we preferred to live rather than die. So we made sure that our headscarves were put on right, our jackets buttoned up, our shawls and pullovers (bought for a high price – the price of a bread ration) well hidden under our jackets. Still hoping to survive, we wanted to stand in Lagerstrasse that morning and go out through the camp gate. The same gate that is still there now, firmly locked.

We were standing in the street leading to the exit, in the camp’s main street. It was one big muddle. Infuriated German female guards were performing their duty, viciously running around the crowd and whipping whoever they could. The crowd remained quiet and moved slowly forward. Several steps forward, stop, forward again, then backwards and stop because something had happened. We did not try to ask and find out what it was, all we wanted was to reach the gate and pass through that special eye of a needle. It did not matter what was going on at the front or back of the line.

We could not look back. We were not curious to know what had happened there. Something must have happened. Some prisoners were being hit in the face for an unfastened button, for a headscarf, for a grimace, for putting a foot wrong, for a protruding pullover, for …the very fact that they had been born and now were inside. Another woman was being dragged out of the line and made to stand aside. We were moving on. She was standing there, showing no emotions, waiting for something. For what we did not know and did not want to know. We did not care, since we could not and were not allowed to do anything to help her. It was her fate. “The same can happen to me tomorrow,” I thought to myself, “Why not?”

On our way, we passed a human rag lying in the ditch, kicked into the mud by the neatly polished boot of an SS female guard. We were a huge crowd, thousands of women, so the SS guards were spoiled for choice. They could kill a few prisoners, knock out a dozen or so, while Death himself had taken his toll during the night… what was that compared with the tens of thousands of prisoners on the daily record sheet in just one death camp?

“I’ll do anything to reach this gate,” I thought to myself, “reach it and pass through...” I could distinctly hear the command hovering in the air, let loose by lots of hoarse throats, though not in unison. The only words crossing one another were “Achtung! Achtung!” the sign that we were approaching the gate, which stood wide-open like the jaws of a monster every day spitting out miles of columns marching out to work.

As we approached the gate, we straightened up, eyes front. The guards counted us again, divided us into groups and assigned jobs. We did not know where we were going, but that did not matter, either. On the right I could see several pairs of boots, their uppers shining and eye-catching. On the left were the jackboots, and next to them the Alsatians and bulldogs sitting on their tails or jumping up when baited and set on the prisoners. The owners of the dogs and jackboots were the SS-men about to “take care” of our group. We were all marching in the same direction. We would return together as well, though some not on their own feet. There was a huge gap between the SS-men and their dogs and each of us female prisoners. They were all certain of returning, but none of us could have been that certain.

What would our day be like and which of us would be brought back on an improvised bier made of sticks or shovels? None of us knew that. We ought not to have been thinking about the present: it would happen without any contribution from us, without us stopping or assisting it. We ought not even to have dared predict our future. Passiveness and indifference were our sub-conscious escape from the reality of the camp and from death. Thinking, submission to foreboding, reasoning like free people, looking for sense, and any signs of defiance had a destructive influence on our psyche. Trying to survive for the day, to survive each of its hours, depended among other things on our apparent acceptance of our predicament.

In those places of extermination, cut off from the rest of the world, the only truth was death. It existed everywhere: in the barrack, in the Lagerstrasse, in the sickroom, in front of the bunkers, inside and behind the gate, in the cells underground, at every moment of night and day. Death was hiding in the whips, truncheons, and hobnailed boots, in the guns and syringes, in the tins whose deadly contents were poured into the gas chamber. The earth, caked or mud-covered, was soaked through with death, death was in the air and in the sky veiled with fumes and smoke. Deadly were the high-tension wires and gun barrels sticking out from the watchtowers around.

There was no motto over the gate into Birkenau. Our counterpart of “Arbeit macht frei” were the constantly smoking chimneys that we could see from afar. The clouds of smoke above the barracks did not speak of death but of its consequences. As we went out to work we left the crematoria behind. What lay ahead was a flat, distant expanse and a glimmer of hope that we would survive at least that day. On our way back to the camp, tormented by hunger, lack of sleep, and tired after the long march, we gazed at the angular chimneys. We staggered on, closer and closer to the chimneys with every step we took. The smell of burning bones and smouldering hair drifting over the camp made our throats sore and blocked our lungs, leaving us breathless.

As we got nearer and nearer, we saw high-sided trucks being loaded up with female corpses. We saw prisoners heaving wheelbarrows or carrying stretchers with the corpses of those who had died in the camp hospital to the huge “depot” located near Blocks 25 and 26, from where the corpses were taken and hastily burned.

Usually, our group halted for a moment in front of the gate. Other commandos kept coming up for the evening roll call. We had to enter the camp “smart”: so, as in the morning, we made sure that our scarfs were tied properly, and pulled our shoulders back. In the evening we usually marched before the camp commander and group of female guards calmer than in the morning. The dogs did not bark. To make our return more of a mockery, for a certain period the camp orchestra played us in. The SS female guards did not yell at us. The commander carelessly counted the incoming columns and registered the number of prisoners, the quick and the dead, the latter brought in on stretchers. The corpses were left at the inner side of the gate.

Once on Lagerstrasse, the regular columns hastily changed into a mob running with what strength it had left for the barracks, clumsily and inertly, rolling like the waves of a suddenly swollen river. The hope of a bread ration, and perhaps something to go with it, made us move faster, push our way in, take others over regardless. Those who fell back might not get any bread, and lose hope of survival. The noise of thousands of hungry women calling one another and shouting, mixed with the clatter of stamping clogs and the crunch of the gravel under their feet, transformed into a horrible cacophony rising over the entire camp.

In rainy weather this race for the barracks turned tragic, since prisoners got stuck in the mud and could easily lose their heavy shoes. The weak, the old, the sick, and the clumsy fell and usually let go of their lives in that mud. When an SS guard saw someone collapse, she rushed towards the woman who was trying to rise, hit her in the face, and finished her victim off with a kick. Then she made a loop with her belt, put it round the victim’s wrist and dragged those shreds of human misery to a place where the corpse would be noticed and recorded, to prevent problems with counting at the morning roll call. I witnessed a lot of such situations.

Who could have helped a prisoner who paid with her life for a tiny ration of bread? Nobody, not even her family and those who were very sensitive to tragedy could do anything. Neither could the functionaries, many of whom were as cruel as the SS guards. Sniffing out benefits, they hoped to get an extra bread ration left unclaimed by those killed on the way from the gate to the barrack.

In the sizzling hot summer of 1944 the overloaded gas chambers and crematoria could not keep up with killing and burning the people served up to them, so stacks of human bodies burned in ditches dug along the river. Grey smoke lingered low over the land, heavy, dense, saturated with the world’s biggest mass extermination, its biggest mass tragedy. The ashes left of the bodies that were burned were sprinkled over the fields in the neighbourhood. The fires consumed all those who were brought up in trucks, padlocked railcars, and those who passed through the gateway to death on their own two feet. Hundreds and thousands of human lives went up in smoke, killed on an everyday basis on a wide stretch of land segregated off from life by a cordon of SS-men, a ring of watchtowers and high-voltage electricity endlessly circulating in the barbed wire around the camp. This volcano is extinct forever now, but it is still smoking, sending up the fumes of death and confirming the truth about the mass extermination programme, fully planned down to the smallest detail, for all the camps dedicated to the destruction of humanity and testifying to Hitler’s consistent policy of warfare for unrelenting rule over the whole world.

There is a limit beyond which a particular individual in a countless mass of people is completely defenceless against annihilation. The violence of the concentration camps that crossed the limit; there was no way to oppose it. If you do not understand the size of that violence, you will not be able to understand the mentality of the countless, resigned prisoners who were forced to accept the fate which others brought upon them.

I feel quite uncomfortable when I have to answer frequent questions like: “There were so many of you and you could not rebel against the Nazis?” I can give only one answer: “No, we could not.” It is extremely difficult to explain this issue to those who think in the categories of this world and not of that camp world. Indeed, we allowed ourselves to be tormented, murdered, humiliated and burnt because … it was the word “death” and only death that was written over the gate of every camp so innocently called “a concentration camp.”

It is very difficult to speak and write about our vulnerability to the Nazi German violence, about the needless deaths, about the terror invented and scientifically planned, since we do not have the right words and definitions for it. Those factories that burned human lives to a cinder have still not been given an adequate terminology. Those who created new terms and names found themselves helpless in the face of those facts, as if afraid of touching the monstrosity and barbarism of the 20th century. The cynicism inherent in killing by Zyklon B or phenol jab, in burning victims to death and tolerating epidemics of all manner of infectious diseases has no counterpart in the whole of history. I hope it never will. Only the word “death” has always been the same, unambiguous and seemingly sufficient. Its common meaning is associated with graves, cemeteries, places of last repose, but you will not find such things in Auschwitz or other places of mass extermination. The ashes came to rest on the ground, and have clung to it for good.

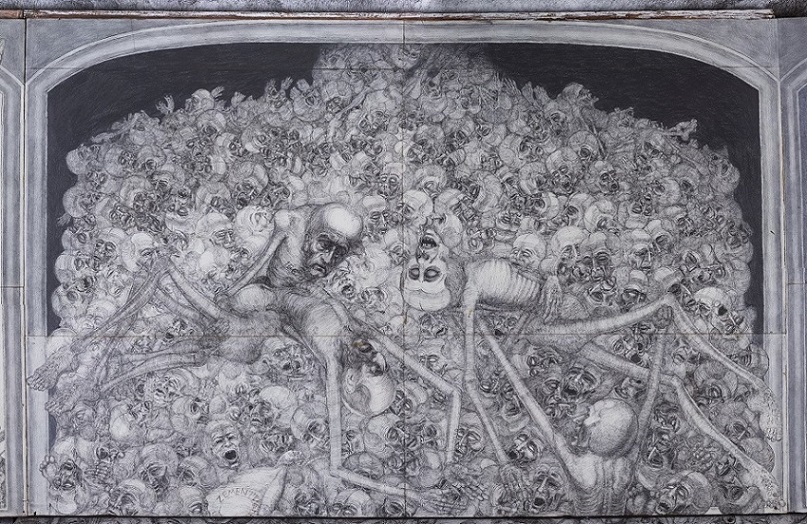

Triptych (The Crematorium Grate). Marian Kołodziej

In Ravensbrück the incinerated bodies of murdered women prisoners sleep the sleep of death at the bottom of the lake adjoining the camp. Whenever I go there, I sit on the concrete bank to “gaze at the lake.” Behind me is the original high wall, part of the camp’s perimeter fence, and adjoining it the single-storey, whitewashed and plastered crematorium as well as the bunkers, now serving as a museum. You can still see the narrow strip between the high walls where executions were performed. I look at the shining surface of the large lake and can see some stately swans gliding on the water, and colourful ducks and common moorhens dashing about between the swans. The statue of a woman holding her child – the Pieta of Ravensbrück – towers over me on its high plinth. In the distance, on the opposite side of the lake, you can see a church tower and the roofs of the houses of Fürstenberg. Not far away from me on the lakeside there are a few anglers.

The farther and deeper I stare into the lake, trying to see its bed, the feebler the rustle of the bushes, the splash of the waves on the shore and the squawk of the waterfowl. I am overwhelmed by the silence and disturbing tranquillity of the lake – the quiet of the grave. The natural beauty of this place mixes with barbarity and genocide. The ashes of about ninety-five thousand women prisoners rest on the bed of the lake. They were brought from all over Europe, a high percentage from Poland. Here they found eternal peace. Here they bade farewell to their families and homelands.

The death camps have brought a new concept, the concept of mass death and mass dying. The exception was the death preceded by imprisonment in the bunker . Isolated and torn away from the masses, the prisoner stood in the bunkera in absolute loneliness, on the threshold of her own life as it slowly ebbed away. On the basis of my own experiences, I can say that the tragedy of such a death was the awareness of dying without the right to say goodbye to the world, to a world that would never know the prisoner’s last glance, words, or thoughts. The tragedy of seclusion was aggravated by the feeling of powerlessness, that there was no rescue, only hopelessness.

Death ranging from death in absolute solitude to mass death, negating the idea that “everyone dies alone,” became the universal rule in the 20th-century death camps, in the Nazi German programme of genocide. It was manifested in mass executions. The work of destruction was performed in fenced-off precincts specially designed for such practices. To die in the camp was but the consequence of the first step made by the prisoner on the premises assigned for just that purpose. Camp death was bred in scientific institutes and laboratories, it inevitably followed from political ideology and propaganda, it was spawned in the brains of madmen and all those who adhered to this madness. That death, a wilful act of destruction, differed from all the kinds of death that the world had seen. It awaited everyone who had crossed the threshold leading into its domain.

Why was it that I did not die? I think that I was being driven towards the goal which had been ordained for me but I did not reach it in time, or – in other words – the approaching death did not manage to snatch me, though I brushed against it, as though walking with it arm-in-arm, I felt it closer, then moving away, I breathed its stench pervading the air, I got to know it to the backbone. Perhaps an oversight? Or, perhaps, some other powers, independent of the force of the sentence that determined the fate of so many people, had the command of my life?

All the signs and portents seemed to indicate that I was to be killed in the Gestapo headquarters in Zakopane, one of the causes behind my attempts to escape. But the Gestapo head, Weissmann, decided that Tadeusz Popek, the co-founder of Konfederacja tatrzańska (The Tatra Confederation), our resistance organisation, would be shot there, while I was to be deported to Auschwitz where the tiny lice would finish me off. Such were his words. Shortly on arrival at Birkenau I contracted typhus. I was in the hospital with a high fever. I saw numerous women dying. The corpses were pulled down from the bunks and dragged out on blankets over the unpaved area leading to the gate. Treatment in a concentration camp hospital was a fiction. The small aspirin ration for hundreds of sick prisoners was only a security measure to stop anyone from accusing the camp authorities of not treating and helping the sick.

I regained consciousness when Mengele, one of the most infamous perpetrators of genocide, came to my block to select prisoners to be gassed. I remember perfectly well my fear, not of being crossed off the camp register and sent to die, but of falling and getting hurt while coming down from the top bunk. I still had some influence on descending from the bunk, though it was precarious and taxed my strength, but none of us had any influence on descending into death. If you were facing ultimate defeat, all your efforts suddenly came to nothing. Your mechanism of thinking switched off automatically, as if the whole of reality and any hopes connected with it had vanished without trace. Mental death ensued, and all that was left was worrying how to manage to make your last effort on your thin, staggering limbs in order to obey the last command. This sort of “semi-death” was strange, a death you did not stop to consider at the time. If it was not followed by a physical death, you could reflect on it in retrospect.

Weissmann was wrong about me, and Mengele did not do his job properly. They were not the only ones who were wrong, and I was not the only one who survived. They did not imagine that some of us could survive, and that remembering the facts very well, we would use them to accuse those criminals. They did not take into account that the end of the war would stop their escalated actions to exterminate all of those they had destined to die. Indeed, how close they were to success.

There were no windows in the hospital blocks. In the dim wards lit by a few lamps under the roofing, sick prisoners lost and regained consciousness; their thirst for life was mixed with their passing away, their glimmers of hope with death. The bunks buckled while prisoners climbed up and down. There were no bedsheets. Straw and wood chips dropped out of the torn mattresses. Lice nestled in the dirty blankets. There was no water for a proper wash.

You could not imagine a gloomier nadir to human misery. The thin, stiff corpses – though sometimes rigor mortis had not set in yet – were dragged along out of the dingy corners one by one and assembled in piles, then sent to be burnt.

In their free time the hospital staff, especially the German female prisoners, used to eat meals which they had prepared themselves, giggling a lot. They did not mind that behind the door of their room there was a pile of corpses, like a heap of rubbish, waiting to be cleared up. The abominable screams coming from their room could be heard all over the block. It was in this bustle, filth, and darkness that people’s lives were slowly being extinguished. The dying were “numbers” devoid of names, age, nationality, or religion, devoid of any rights that the sick deserved in their suffering and dying.

Only once did I hear some Yugoslavian women singing the penitential psalms at the bedside of their dying fellow-inmate. This seemed so odd to me, like a supernatural phenomenon that had surreptitiously strayed into our world. When I was in the hospital block, I once saw the German women carrying a new-born child around the block. They sang lullabies to the baby. They passed it to one another to enjoy to the full, before entrusting it to the final arms of death.

I was discharged from the hospital block, which meant being sentenced to further vegetation. Indeed, I had been so close to death in that block. I could hardly believe that I was alive again, that by the decree of fate I had to live. I staggered towards my labour block. The mud and the incredible emptiness of the depopulated camp filled me with fear.

My long waiting for the prisoners to return to the camp after work seemed like eternity. Nobody in the barrack noticed me, nor wondered that I was alive. I reported my arrival to the guard so as not to miss a bread ration in the evening. The block leader, the block services, and night shift guards were busy with their duties. For them one “number” more or less did not make any difference. Outside in the camp SS-woman Hasse, wearing gloves made of human skin, was shooting at stray prisoners. Sometimes she fired to scare others. Then she dragged the dead body to a prominent place, so that she could register it with the day’s losses. Knowing that, I did not intend to leave the barrack. So I holed up in the corner of the bunk, and looking through the filthy window I counted the bricks in the wall of the opposite barrack.

I did not reflect on my experiences in the hospital block, glad they were over for me, and with every day would be further and further away. However, those experiences stuck in my memory so firmly that even today I remember some of those images quite clearly. They come back whenever I recall them. They live with me…

As a rule, we neither analysed nor discussed incidents that happened in the camp, not because the time and place weren’t right for it, but because reviving them could have been suicidal. We were like a field of wheat that bowed in the wind and rose up when the wind stopped blowing, or was flattened by heavy rain and never rose again. So our mental disposition accumulated the monstrosity of our camp lives and sealed it automatically, enriching, hardening, or breaking us. Sharing our experiences, especially the most dramatic ones, would have made no sense. We were all in the same boat and on the same course. Did we keep our silence? No, we did not, but the subjects we talked about did not go near the omnipresent death. We did not devote any time to it, neither did we let it devour whatever remained of our life and strength. It was enough for us to know that death was there. Those who survived are now releasing their deeply hidden experiences of death, trying to show its real face.

I was a very sensitive child, but at the same time – tough. I hardly ever cried and if I did, it must have been for a serious reason. But I could not stop crying on reading the poem Jaś nie doczekał (“Johnnie did not live to see it” by Maria Konopnicka) or the short story Janko muzykant (“Johnny the Musician” by Henryk Sienkiewicz). The little boys in these works of fiction were so dear to me that I experienced genuine grief over the loss of them, forgetting that they were fictional characters. I was moved by every death, and funeral marches made me tremble. I felt deep sympathy for the family and relatives of the deceased. Death struck me with its gravity. I treated funeral ceremonies as sacred rituals without which the issue of death would have seemed profaned and stripped of its due dignity. When a funeral cortege was passing, vehicles and pedestrians would stop, and the men would take off their hats. The coffin was carried on the shoulders of the deceased person’s colleagues, who paid their last respects in this way. The priest leading the cortege, together with the organist, sang the obsequies in Latin. There was also a choir and an orchestra; wreaths, bunches of flowers, the family in mourning and … tears on the faces of those present at the funeral. Could I have imagined that a funeral could be organised in a different way? Could it have been completely different?

I learned that it could have when I saw the motto “Arbeit macht frei” over the gate of Auschwitz. I was standing in a group of about a dozen women delivered to the camp on 1 December 1942 from the Montelupich prison in Kraków. We hastily ate the food we had brought with us, as Auschwitz prisoners who passed by had warned us that we would have to leave all our food. Soon we spotted a cart with very high sides emerge from the camp. A team of prisoners was pulling it slowly and with a lot of effort. Its load stuck out over the top of the cart. Beneath a cover of blankets something was moving to and fro. The prisoners pulling it were bent double. Blood was trickling out in rivulets from the cart, and other prisoners were wiping it away with sand. There were no blankets on the back of the cart. Dozens of naked lower limbs were dangling about to the rhythm of the movement of the wheels, feet hitting and bouncing off one another. Rigor mortis had not set in yet in the bodies on the cart…, only we froze with horror. Death, funerals and the last passage did not evoke any emotions or tears. When we saw such cruel deaths, all we could do was to remain silent. On the threshold of the death camp, we endured the first blow, our baptism of fire.

The first act of our self-defence was done. Something in us jammed. Our nervous systems received and registered the stimuli, but did not react. Only afterwards did we realise that this attitude to death would help us live and survive, allegedly.

The hearse of a dishonoured death, humiliated, reduced to basic concepts, surrounded by derision and vulgarity, evoked and activated a hitherto dormant desire to play for our lives. A world of abnormality, a world of madness opened up before us. To be found in such a world meant the same as jumping into water if you could not swim. There was no turning back.

We did not make any comments. Not a single word was said. The process of psychological change had to take place without any help. Intuition replaced logical thinking. Our youth (we were 20–25), and its entitlement to the right to live, now stood facing death and was apparently defenceless, shackled, and alone in a crowd. Time would confirm this truth.

Selections were applied to regulate the mortality schedule when epidemics of typhus, other contagious diseases, and the daily death toll did not come up to the mark. The food rations stipulated for all the prisoners could not exceed the prescribed limit. It was easier to kill a hundred or a thousand people than to prescribe the same number of rations more. So the mass extermination was the outcome not only of ingrained sadism, racial hatred, the ambition to rule a world purged of the disabled and the old, but also from cold calculation. The characteristics of the German economy and economising, when transferred to the death camps helped to make the Third Reich’s select German nation prosperous.

That is why the eyes of particular SS women guards did not always look hostile when they selected prisoners to be gassed. Often they harboured a chauvinistic rationality, their commitment to Nazi German nationalism and concentration camps, as well as a vision of personal reputation and affluence. Though, usually we could see nothing special in their eyes, as if their work was not about life, but sweeping up rubbish or pulling up weeds: an easy job, well-paid, performed in a uniform; they had boots, good food, dogs and holiday leave. They could also count on the SS-men’s merry company, entertainment, perks, senior officers’ visits, the absolute submissiveness of the crowds they “looked after,” and a sense of power and security.

As we stood dead still in front of an SS-guard, watching not only her face but also her whole figure, we were petrified, in the face of death, which in those circumstances would become reality for us, and life an illusion.

I was waiting outside hospital admissions together with inmates I did not know. I had a high fever. It was raining. I thought I would be sent to the hospital block. I knew that people had been killed with phenol injections in admissions as well. Yet I was not afraid. I was extremely weak. I leaned on the wooden wall, waiting for something, anything, no matter what. I wanted to sit down somewhere. I wanted to lie down somewhere and just stay there… I did not want to suffer any longer. I was soaking wet. Some SS-women were running in the Lagerstrasse. One marched past me. Prisoners were carrying corpses on stretchers to Block 25. Four women were making a big effort to carry a stretcher full of bodies and getting stuck in the mud. Another two were pushing a dead inmate in a barrow the wheel of which stuck in a rut. They could not pull it out. The corpse fell into a puddle. They had to make another big effort. It kept raining heavily. I was watching the situation and envied the dead that they did not feel the cold anymore, even in a puddle and soaking wet; they had achieved the most comfortable condition. The only emotion I had was envy. I would not feel sad to leave such a world, a different world had completely vanished from my vista.

The death of those inmates whom SS guards pulled out of the marching column with the curved ends of their sticks was a great human tragedy. Dying of exhaustion and disease was salvation. I waited for this salvation outside admissions, soaking in the rain, freezing and starving. I waited patiently like other inmates in the same conditions. We could not cry for help. Some unexpected event might have happened. It might, but need not have.

Death in the concentration camp did not have angel’s wings. It was naked, stripped of sacrosanctity and dignity, of all feelings, words, hymns, and ceremonies of any kind. It was gloomy like night, quiet and nameless. Nobody wept, nobody mentioned it, recalled it, nor was shaken by it. It was lodged in every one of us. No graves were dug for the murdered. Their place of burial was unmarked. There was no drum-roll. Not a single bird sang. No use generations now alive looking for traces of that death in the vast charnel-house that was Auschwitz-Birkenau, a symbol of torture and oppression, of fighting for your own life and for the lives of others, a symbol of heroism. No use asking about the conditions in which your dearest ones died on this singular field of honour. There is no answer. You have to understand this death and weigh it up by the measure of its mass and magnitude, by the four million hearts extinguished there.

Translated from the original article: Apostoł-Staniszewska J.: Wobec śmierci w Brzezince i Ravensbrück Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1981.

Notes:

a. Prisoners condemned to die in the bunker were left there to slowly starve to death.