Author

Adolf Gawalewicz, 1916–1987, lawyer, writer, member of the Polish underground resistance movement, Auschwitz Birkenau survivor No. 9225, later confined in other concentration camps (Buchenwald, Mittelbau Dora, and Bergen Belsen).

For a long time I have hesitated about the form I should use to present some extracts from my recollections related to my experiences in Auschwitz. The professional character of the journal prompts me to give a dispassionate, accurate account sine ira et studio.a Yet, my recollections are to be reminiscences of personal experiences, so how can I avoid emotional elements and very frequent subjective evaluations?

I would like my account – like those of my fellow-inmates – to be a certain, although minor, contribution to the materials relating to the psychology of how to endure terror as well as physical and psychological suffering. Therefore, on the basis of my personal experiences, I would like to help to answer the questions: “which psychological and physical conditions made it easier to survive, and what was due to random chance?” As my main interest is to reconstruct what a prisoner thought and felt in those difficult and often dramatic camp situations, I intend to describe only the most crucial facts.

At this point, in my introductory remarks, I shall consider the doubts about the value of recollections if they are told after many years. Camp experiences return even in our dreams. They keep coming back, especially when we are facing difficult decisions or when we are troubled by serious failures. That is when sharp images of those years appear in our dreams. You cannot forget those times.

Additionally, I need to explain the title and subtitle of my account. “The waiting room to the gas” is neither used figuratively nor aimed at shocking anyone. That was indeed the purpose of Block 4 in Birkenau in its B Ib section, then number 7, and called the Isolierstation. I had to live in that block for an extremely long period, considering the intensity of my experience, from 20 April till 16 September 1942.

The history of that block can be divided into two periods: to 4 May 1942 and from that day on. It was the date of the first selection of Birkenau prisoners to be gassed, which also meant the almost complete extermination of the remaining inmates of Block 4. On that day, i.e. 4 May 1942, Block 4 was renamed Block 7 – the Isolierstation, and started to operate as “a waiting room to the gas.” Commencing from that date, Block 7, which had a perimeter wall put up around it, served as a temporary hall for prisoners who were sent there from the whole camp to be gassed. So I witnessed and went through the events that preceded the beginning of the mass murder of people from the camp and from outside in the gas chambers as well as the first months of the implementation of the genocide plan conducted in that way.

Afterwards I never met any of those fellow-prisoners again, either in the camp or after liberation, of those who had been sentenced to extermination in Block 4 in Birkenau between 20 April and 4 May 1942. So I am entitled to consider myself one of the few witnesses, if not the only one who survived that time. Though a certain number of prisoners managed to leave the Isolierstation, after staying in this block after 4 May 1942.

My experiences of staying in this “waiting room to the gas,” if I were to rank them on a weird scale of camp experiences, would come at the very bottom of the scale. That is why, in retrospect, these experiences constitute my subjective measure of that “inhuman time” in my recollections of imprisonment (September 1940 – April 1945).

All of what I had experienced before seemed to me a kind of background, preparation for this encounter with the macabre; everything that I was to experience later is also related to this story. Namely, it seems to me that to a great extent I drew my psychological strength to endure further trials and turns of fate in the camp from reasoning along this line: “what awaits you, what is happening now, is not – since it cannot be – more terrible than what happened there, and after all, you were able to endure that, so…”

The subtitle says “from the memoirs of a Muselmann.” It so happened that the fate that befell me assigned me a place in the category of prisoners counted as Muselmännerb very quickly, already after a few months in the camp and for a particularly long period (1941-1943), considerably longer than on average. In the eyes of my mates, I enjoyed (if I may say so) the opinion of a perpetual and yet still live Muselmann. For years my appearance was the spitting image of Professor Olbrycht’s definition of “the dried-up form” of starvation disease, “in which the starving individual looked like a skeleton with his skin stretched tightly over his bones… ”

Hence, “waiting room to the gas” and the condition of the Muselmann, especially its physical form, were like two labels to sum up my fate in the camp. I experienced all the stages of the Muselmann’s career (except, of course, death).

The beginning of this career was very banal: by March 1941 I had got through the first stage, i.e. I had reached the state of utmost inanition and naturally, I got durchfal.1 I fainted during the morning roll call. Two fellow-prisoners took me to Block 20. The roll call would be over in a minute, and the order “Arbeitskommando formieren”2 would be given. So, all the three of us would have a better day. I may be admitted to the hospital ward and my caregivers would not march off with the work groups but may skive in the camp doing some quiet activities. In admissions I spotted some wonderful instruments from the normal world: a thermometer and some scales. The thermometer showed I had a high fever, while the scales balanced up at 36.2 kg (79 lbs 10 oz.). Later, when I arrived in Block 15 (Block 20 at the time) with the Zugang group,3 I was not surprised to hear, “Coop up this one on the straw mattress next to the door.” We all know: less trouble with body disposal.

What a feeling of colossal relief and release of tension! You can sleep, nobody is beating you, no need to carry bricks, cement bags or other awful, wet, frozen and slimy objects to Industriehof II (called Bauhof at the time).4 Hunger wakes me up; it is time for the midday roll call. I am told I do not have to get up. The man next to me is dead, but they are bustling around to get his body up in a position qualifying for a bowl of soup. I am being lulled into sleep with a sweet feeling that when the gong rings before dawn I will not have to run half-naked and barefoot, hurried on with a whip, to the snow-covered yard in front of Block 7, pretending to be washing in water collected from melted snow in wooden marmalade pots, and at the same time dodging our Stubendienst Wilhelm Żelazny or – worse still – our Blockführer Alojzy (rightly nicknamed “Bloody Alojzy”).

When my first night in hospital was over my fellow-inmate Władysław Fejkiel – then working as a male nurse – said to me, “What a trick you played on us. I was sure you would not get through the night to roll call and I’ve already done a Totenmeldung5 for you.” I answered that I was sure I would get through it all because I wanted to return home to Kraków, to my mother.

As compared with the living conditions in the blocks and Arbeitskommandos, the camp hospital, which in those days had only a thermometer, scales, Schmerztablette,6 Tannalbin, and what looked like a reminiscence of straw mattresses, was, however, a wonderful institution. A sick person with a prison number tattooed on him lying in stinking and stuffy conditions, or worse – in the biting cold (Fenster aufmachen!),7 but in relative peace, not facing any direct danger, and more importantly, not being forced to work hard to the limit of what he could stand physically and psychologically – experienced a feeling resembling happiness. A similar feeling must have accompanied a hunted animal that managed to hide in a burrow.

The camp was a microcosm ruled by laws which were a specific deformation, degeneration, yet sometimes also a noble sublimation, or a fairly close analogy to order, the rules and ethical principles established in a normal community. I have to remind you of this truism, because I want to use a term borrowed from normal life, namely “convalescence.” If you want to write about the recollections of a patient on the health service available in the concentration camp, you cannot overlook the period of “convalescence.” It was a high price to pay for a comfortable time in the hospital block.

After having been discharged and sent back to the camp I was given a leichte Arbeit [a “light job”]. Along with a hundred almost identical Muselmänner, I greeted the spring of 1941 in the Holzhoffe8 doing the so-called easy job: chopping wood, cleaning surplus building materials using glass, straightening nails, etc. On the whole, these activities would not have been more strenuous than other jobs if they had not been specifically “diversified” by brutality and abuse. We had very frequent visits by SS-men with dogs (one SS-man called Perełka [Pearl] outdid them all). I am very fond of dogs, and even when I was in a group of prisoners being baited with dogs, I never tried to run away. I bear no personal grudge against the dogs trained by SS-men. A dog rushed at a Muselmann whose movements were nervous, tore off a piece of his skin, usually from the back, bit him, and depending on the dog’s training and additional orders, harassed its victim.

Official assaults on Muselmänner doing a leichte Arbeit were organised less frequently. I experienced them several times. They usually began with prisoners being ordered to carry bricks, planks, and similar materials im Laufschrift.9 Then the functionaries recruited for the task joined in and massacred the prisoners. Quieter days and hours depended on the humour of the Kommandoführer and kapo. Often they would not allow prisoners to sit while doing jobs that could be done in sitting positions, or they burdened prisoners with work beyond their strength.

Why did I endure this spring of leichte Arbeit? Perhaps thanks to the fact that my almost eight-week stay in the hospital block allowed me to more or less recover my psychological balance and made it easier to adjust to the atmosphere and conditions in the camp. When I arrived at the camp as a Zugang, my psychological condition and attitude had absolutely nothing to do with heroic qualities. My first day in the camp, spent on carrying boxes of corpses and buckets of water, and the whole ritual of “welcoming” a transport of new arrivals – all of that made me fall into a state I cannot define.

Still today, when I try to put the first period of my time in Auschwitz in one word, I call it “terror”; the terror was so strong that it caused my entire body to tremble almost all the time.

The first, slightly soothing medicament was meeting friends who had arrived at the camp earlier and were still alive. Their words of comfort and the gift of a cap brought me some relief (since for some from my transport there were no coats and caps left during that severe winter of 1940-41). Even the fact that other inmates stole my cap very soon, when this naive Zugang was in the outdoor latrine, the only toilet at the time, which was crowded after the evening roll call, even that did not undermine the beneficial effect of those friendly words and gestures. The state of trembling terror combined with my fervent wish not to live to see the roll call at dawn accompanied me until I was assigned a place on a straw mattress in the hospital. I got it all off my chest. I was alive. The sun went up higher and higher in the sky – “Just got to make it to the spring, buddy,” and this characteristic shoulder shrug to warm you up. Moreover, I was alive because I listened to the advice of experienced inmates. Nobody ever stole my bread ration for the simple reason that I ate it at once. I never bartered soup or bread for a cigarette in the place known as the “street market.” I never yielded to the temptation of trying a delicacy – a slice of raw potato with a pinch of “saccharin,” which my fellow-prisoners from the potato peeling room recommended.

However, a thirty-six-kilo man experienced ravenous hunger. Zdzisek “Naftali” Stańda thought it was fair game to slightly reduce the extra soup and bread rations that his Blockführer (in Block 15) arranged for himself. So in the spring and summer of 1941, quite often I got an extra, illicit ration from this inmate and friend of mine. How unbelievably vast was the capacity of the Muselmann’s stomach! One Sunday in summer, my friend Stańda ran up panting and let me in the side hall of Block 15. Inside there was an almost full ten-litre pot of watery potato soup. “Eat it quickly, while I stand on the lookout.” No time to find a bowl, spoon, or other utensils. Using my cap, I greedily scoop up the wonderful, mushy soup and lap up this special nectar. Within a few minutes I must have downed some eight litres of it. With a full, squelchy and happy stomach, I lay down on the gravel of the roll call square – the orchestra was playing a Sunday concert. It was my record eat.

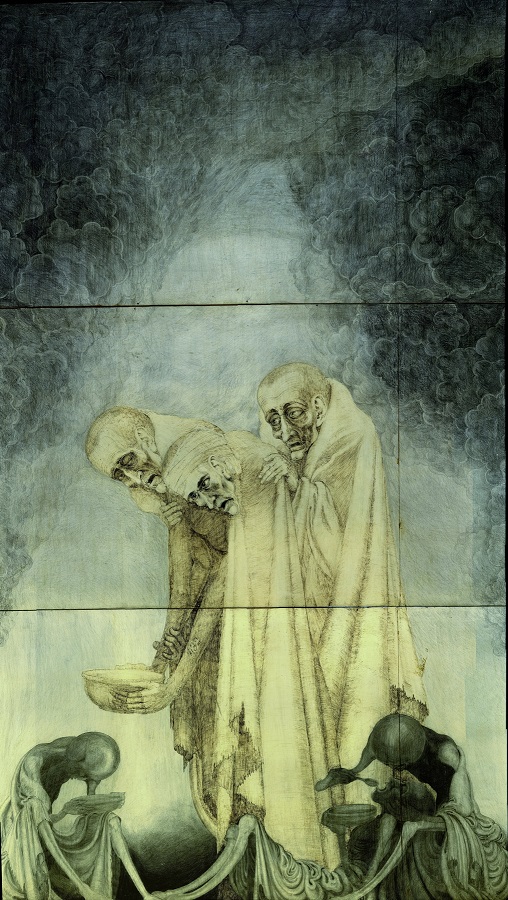

Muselmänner. Marian Kołodziej

The Muselmänner were a reserve workforce to cover gaps in other commandos. Following the command “Arbeitskommando formieren” at the end of the morning roll call, the kapos used to run up to the Muselmann commandos and select as many people as they needed. That is how I was able to work as a roofer or gardener (woe to the beetroots that my short-sighted self had to weed). I also worked as one of the draught-horses on the Rollwagen, a tanker truck full of excrement from the camp latrine which we had to take to the vegetable frames. This job in the so-called Scheisskommando [shit commando] had its advantages and disadvantages. The former included the fact that the stench that came from us put the SS-men and functionaries off from any close contact with our bodies, viz. beating us. On the other hand, in the block there were difficult and bothersome situations: “Stubendienst, don’t give any food to that one as he stinks of durchfal…”

After a few months of this type of convalescence, I landed up in Block 28 admissions again. I had developed Lungenspitzenkatharr [pulmonary apicitis]. I was put into Zygmunt’s ward in Block 28. Then I returned to the camp, got durchfal again, and moreover, my mate Fejkiel told me, “You’ve got tuberculosis, but it’s a gentle form, fibrous TB.” It was summer, and my friends were again helping me by providing more food. I went back to the camp, to the Muselmann commandos and blocks, and again set to “an easy job.” During this period, I was sent for some time to Block 19, the famous Muselmann hosiery shop. It was a Schonungsblock, a block for convalescent prisoners.

Skinny figures sat working choc a block on the wooden bunks and stools, crocheting stockings, knitting pullovers, caps and other things like that – a higher category of work. The rest of the populace prepared the raw material, unravelling old pullovers and stockings. My awful short-sightedness! Alojzy had an old aversion to people wearing glasses and just at the beginning of my stay in his block he freed me from my glasses with one blow. What kind of work could I do in the hosiery shop? I was assigned a job the devil himself would not have invented better if Auschwitz foremen still had any need for his inventiveness.

I was ordered to sit on a stool at a large table. My workmates were mentally ill. We were to wind the recycled yarn and thread into balls. I spent two days with the insane. I cannot describe the terror and fear of those hellishly long hours, as long as eternity. All the mental cases I met during that time had gone mad as a result of torture under Gestapo interrogation or because their psyche could not bear the conditions in the camp. Even a non-professional like me could easily discern from their gestures and garbled speech that that was the cause of their insanity. My request was considered and I was again assigned work in the camp. Not long afterwards all of my poor workmates at the madmen’s table in the hosiery shop were exterminated.

In Muselmann Block 9, I was put to an easy job again. Lice infestation was spreading rapidly in the camp. Epidemics of typhus were starting. Naturally, louse searches were very frequent in my block. They found plenty of lice on my body and I was ordered to take a special bath. Together with a few other unfortunates I had to get into a barrel of highly chlorinated water, and the kapo “himself” cleaned my body with a scrubbing brush. The chlorine and the scrubbing brush on my abscess-covered body saw to it that hygiene was kept.

One fine, hot day at the turn of August and September, the inmates of Block 9 had the opportunity to learn the taste of the selections in store for them. After the midday roll call our block was kept out in the yard, standing to attention as punishment for some misconduct. We were kept standing for hours, with all the harassment that normally occurred in such a situation, especially against those who could not keep up on their feet or control the call of nature. Every tenth prisoner was selected for the bunker of Block 11.c I was in the second row. “Mützen ab!”10 Counting to ten! The tenth man was yelled at, “Out!” I was standing there, wondering if I would be one of them. I did not want to be tenth and did not wish it on any of my mates, but… One of my senses told me I would miss unlucky number ten. Neither of my neighbours on the right and left would be in danger. But as the group of oppressors slowly passed along our row counting the prisoners, the one second left from me, who was not endangered, just could not bear the nervous tension and started to go pale and stagger, drawing their attention. “Raus!” They started counting from the beginning. A chance occurrence had suddenly intervened in the lives of dozens of people whose fate seemed to have been determined already.

Again, my case can be an excellent Totenmeldung topic. I had the luck to return to the hospital in Block 20 just at the right time, when most of my companions from Block 9 were being experimentally gassed in the bunker of Block 11.

Fellow-inmate Stanisław Głowa operated the phlegmon on my left arm using an ordinary clasp knife. There was no anaesthetic, of course, but the treatment was successful. Another inmate called Szymański fed me with the bread rations left by those who had died in the typhus ward.

It was the autumn of 1941. For some time transports of Soviet prisoners-of-war had been arriving. The current political situation was summed up for us in Dante’s “lasciate ogni speranza.” Yet, there were still people hoping against hope. Even in the hospital blocks where every Sunday events – cultural entertainment to uplift hearts (I have no proper words to describe them) – were being organised. I joined in – me, a Muselmann with abscesses made even more painful because of the lice that nestled in them, I was writing poems. For one of my poems, I was awarded the most wonderful prize in the world: a bowl of soup with noodles. “I tell you, when he used the ladle to stir the soup, he poured me some from the very bottom, soup that was so thick that my spoon could stand upright in it,” as I later kept recalling this moment like the most magical fairy-tale.

I managed to stay in different rooms in Block 20, with short breaks, till 20 April 1942. Still today my memory holds permanent recollections of the events of that day.

Here they are: The engine did not switch on for a long time – ah, this Holzgas!11 So we were standing choc a block in the back of the truck, in front of Block 20. The damp, penetrating cold of the delayed Auschwitz spring was getting through our gimnastiorki (Soviet prisoners’-of-war jackets that had just been issued to us convalescents from Stanisław Rozpęk’s ward; they were similar to scouts’ shirts). It was 20 April 1942, Adolf Hitler’s birthday. There was no formal selection. The day before, a few prisoners had been sent back to the camp, while SDG12 Josef Klehr took our temperature cards to the office. We were given these “scout’s” clothes, but without the coats or caps of course, and those damned clogs for some and the equally hated Dutch-style wooden clogs for others. They told us, “You are convalescents, you’re being transported for an easy job.”

For the less experienced, it sounded quite probable, considering the fact that we were herded out of the block fairly gently, without much beating. But for us veterans, who, like me, had started their second year of living in the block a few months before, that “easy job” had an ominous meaning. The hurried farewells of our friends evoked anxiety. They must have known something: Stanisław Głowa, who put a piece of bread in my hand and had no time for a short talk, and Zdzisek “Naftali” Stańda, who only shouted, “Have a good journey, take care of yourself!” and immediately took flight.

At last, the vibration of the truck as it moved off, and for a moment seemed to damp down my anxiety, which was growing as the slimy cold swelled up. One more glance at the almost empty little street between the hospital blocks, and just at the turning in front of the kitchen you could catch the wonderful, lingering smell of bread. Yes, it was not so long ago that the command Brot holen [fetch the bread], most joyful to the Muselmann’s heart, had passed from mouth to mouth.

The orchestra was preparing for the afternoon concert, the formalities at the Blockführer’s office, and the truck rumbling down the little streets encircled by the main ring of sentries. Julek Mark from the street cleaning commando – that was my last farewell with friends. Turning for Birkenau – so we have a subject to comment on. We do not know much about this large, newly built camp. Recently the rest of the Soviet prisoners-of-war were transported there, and over a thousand Muselmänner the month before. Apparently the horrors of the new camp were far worse than what we Auschwitz veterans had experienced. No sense dwelling on it. We would soon see for ourselves what this new Birkenau version of the camp was like.

We were there. In front of the brick barrack there was a small group, about thirty miserable-looking figures – the rest of the over one thousand prisoners transported there before us. The convalescent prisoners who were transported “for an easy job” a month before. Along the wall of the block there was a neatly arranged row of corpses. It was the day’s death toll. I did not want to ask how they had managed to finish off a thousand inmates within a month, and their companions in distress still left alive did not feel like getting sentimental over it.

Now the fundamental problem was whether they would give us some food and let us go indoors. They neither gave us food nor allowed us in for the night. The functionaries ordered us to stand in even rows. Anyone who fainted and collapsed on the soft, sodden, slightly clayey ground covered with finely crushed brick, was whacked on the head or all over with a stick.

In that situation, there was only one alternative: either he was encouraged by the stimulus and got up, or he enhanced the row of corpses neatly arranged along the wall. That was how my first day began in what would be the waiting room to the gas.

Now I should relate the events that happened within a small amount of time and space: the story of a fortnight cooped up with about 260 people on an area of about 600 square metres (6,458 sq. ft.). Putting it in a brutally vulgarised way, this story can be defined as “the characteristics of certain preindustrial methods used to exterminate prisoners incapable of working, in the period directly preceding the launch of an industrial system of genocide.”

What did these “preindustrial” methods consist of? Here is a difficult and unrewarding attempt to characterise them:

1) starvation,

2) being made to stand at attention in rows,

3) additional torture of prisoners standing in the yard or staying in the blocks,

4) a ban on medical assistance of any kind.

The starvation was gradual. There were days when we did not get any food at all – on average, every other day. On days of absolute starvation, after having stood at attention for the whole day, we hoped that “instead” they would let us stay in the blocks for the night, which usually happened. On days of relative starvation, we got a small soup ration; one litre for 3–5 prisoners. As a rule, this was an “equivalent” for a forthcoming stand-up during the night. Exceptionally, probably at the most 3–4 times during those two weeks, we were given a small bread ration: a 1,400-gram (3 lb) loaf of bread for 8–10 prisoners.

During the day, standing at attention was practically compulsory. We were tormented by hunger and extreme thirst (we got no water), some alleviated that by hallucinating of binges, which would come on during a dreamlike state. We were trembling with cold – we had neither coats nor caps during that rainy, snowy April in Birkenau, we ran fevers or froze, had bloody diarrhoea, abscesses, and scabies. So anyone who survived till the evening roll call dreamt of a quick end or all the luck he could expect: eating and sleeping in a bunk in the block. In general, there was only one real alternative: either sleeping or eating.

Surviving the night up on your feet and living to see the dawn meant only one thing: more standing in rows, which in that condition of growing physical and psychological exhaustion was practically an impossible task, over the course of time achieved to a greater and greater extent by random chance or, if you like, by the law of small numbers.

Naturally, these instances of random chance had to be correlated with, and supported by the prisoner’s special psycho-physical faculty, which was helpful in such circumstances – more on this later.

Starvation as well as standing still day and night did not exhaust the extermination programme for the sick and tormented. During the spells of standing outside at night, the most horrible torture was the “bath”. When the rain barrel in front of the block collected enough water, the usual ordeal of standing was interrupted by the appearance of an SS-man or functionaries. Several victims were chosen. The reluctant were forcibly thrown into the ice-cold water, and the victim was tormented until he drowned. As a rule, if anyone survived the “bath”, he did not live till dawn. He sort of sank into the sodden, Birkenau night, into that lethal, sleety drizzle.

Being allowed in seemed a godsend. Although one part of the block was occupied by 190 Russian prisoners-of-war, all that was left of the original group of about ten thousand, there was still enough room in the barrack. It was not heated at that time, so we tried to kip in groups. You had to use the bundles of musty, damp straw in a smart way and put them under the most sensitive parts of your body. For me that was under my hips, as I had bedsores. I put my Dutch clogs under my head and wrapped my face with a piece of Jacke [jacket]. Soon relative warmth would come from our bodies, getting countless lice to prowl about our abscesses in a zippier way. Then you would suddenly drop off. But in the middle of the night a yell would wake you. A group of SS-men and functionaries entered the barrack. Evidently drunk. A command is given: “stick your heads out!”. One of the thugs, most probably the kapo of the penal company that was just about to move from Auschwitz to Birkenau, used to boast that he could smash his victim’s head with a single stroke of the stick.

Can you describe the moment of silence and horror hanging over our exposed polls? Would it be my head that bastard was going to smash this time? That was the most important and perhaps the only problem in those dreadfully long seconds. Two or three victims, and bits of brain and blood spattered all over the bricks, the mud floor, the walls and beams. And again, immediately, you would fall asleep.

After a certain night, during which there had been another head-smashing incident, I woke up and realised that the bunk we were heads-to-heads with was empty, while in the evening it had been occupied by at least five bedfellows. Only then did I remember that there had been a visit and a heads-out command. Presumably, when the critical moment of selection passed our bunk, my tiredness must have prevailed over the tension of witnessing the next instalments of slaughter, and I must have fallen asleep.

The ban on providing us with any medical help whatsoever was the source of other types of torture. Tuberculosis, typhus, diarrhoea, abscesses, and scabies were the most common diseases that probably every inmate in our group had all at the same time. Here the medicinal charcoal, paper bandage, and scabies ointment available in the hospital blocks were unattainable luxuries. Dr Marian Ciepielowski from Warsaw13 came to see the Russian prisoners-of-war, our fellows in the block. Most of his work was to treat the prisoners’ wounds. I will come back to Dr Ciepielowski later on.

Naturally, our group was shrinking faster and faster. What did you think about if you were still alive and wanted to live? What did you think about up on your feet for 24 hours? Your thoughts went in this way:

1) I have to stay up on my feet because…

2) I cannot allow anyone to lean on me very much,

3) I have to get the warmest place in the middle of the group,

4) It is terribly cold but tomorrow is sure to be sunny…

Anyone who thought any otherwise did not survive. One night a companion of mine still physically fit confided, “I’ve had enough; this is hopeless; I don’t want to live any longer.” Indeed, a few hours later we carried his body out and put it next to the wall. Fourteen days passed. On 20 April there had been about 260 of us including the remainder of the previous transport; now there were just 25-30.

I was still alive. Why? Because I wanted to survive. Dr Ciepielowski and my poor but hardened body helped me.

Dr Marian Ciepielowski lived in Warsaw, at Number 7, flat 4 on Zimna Street. I remember his address very well since it was analogous to the number of my house and flat. This physician deserves a lasting memorial. Dr Ciepielowski was ordered on pain of death not to approach us during his visits to the Soviet prisoners.

This doctor did his best to help us. He smuggled in several bread rations and medications every time he came to the block. I do not know what medications he brought; in the circumstances, there was neither time nor need to ask. He informed me that I had typhus, but thanks to my small weight it was taking a very mild course. Once he said, “You need a protein diet.” There was a bizarre contrast between that and our conditions, and the purpose for which we were being kept there. In fact, my contact with Dr Ciepielowski assumed an extraordinary form and strange highlights. One day he beckoned to me and I followed to the latrine; on the way there you would usually see someone in their death-throes lying in the soft mud; many a time in the latrine there would be a corpse afloat in the faeces. I was given some bread and some pills. And how did I reciprocate?… by reciting some lines from Słowacki’s Beniowski.

Just imagine that weird tableau: the latrine, a floating corpse, bread, and poetry – “Oh youth! You’ll make this swan-like apparition/ Of fire and gold rise, soar above the world!”d I know that Dr Ciepielowski helped other inmates as well. So thanks to him, help, organised undoubtedly not only by him, reached even this completely accursed block.

In the first days of May 1942 the compulsory standing extravaganzas suddenly stopped. A large Zugang group arrived; regular deliveries of soup and bread began; the Soviet prisoners were moved from the block. Nurses and Rudek Różański came from the Auschwitz camp. Blockführer Wiktor Mordarski, Piasecki the clerk, and others arrived. As I have said, the number of the block changed: from four to seven, and the block was now called the Isolierstation.

On 4 May, we were ordered to assemble in front of the block, and told that some of us would return to the ordinary work blocks, and the rest would be sent to “an easy job.”

We walked slowly in single file in front of the SDG. On the left there was a truck waiting for those sent to the “easy job.” The SDG gave the signal – I was with those turning left, for the vehicle. A healthy-looking Jew from Slovakia was in front of me. The bandage on his slightly swollen leg came undone and was fluttering in the wind. Functionaries were overseeing the procedure. Biernacik, the kapo of the morgue commando, was there as well. As we approached the clerk registering our numbers the prisoner in front of me shouted, “I’m healthy; it’s only a small phlegmon.” Then a sudden flash shot through my dull, post-typhus brain. “He’s a young prisoner, and afraid of an easy job…” I turned to Zabierski and said, “I’ve gone through so much, and now they want to do away with me!” Zabierski glanced at my number, looked around, grabbed me and tossed me into the small group directed to the right – still to live – and cried, “Keep him!” I had been saved from the first Birkenau selection for the gas. But I was still in Block 7. New prisoners kept arriving in this block. A vehicle came every two or three days. A contingent was set depending on the turnover of the gas bunkers and corpse-burning installation how many inhabitants of the block are to… this time.

Sometimes, the whole of the block’s staff except for the managers and permanent staff but including the temporary Stubendienst men were sent to the gas. Theoretically, I had no chance to stay in the block for a long time if its inmates were being sent to their deaths regularly – a couple of times a week. There were also rare cases of people being sent back to the camp. But me, what with my Muselmann’s post-typhus condition… Yet, I was alive and had managed to dodge successive selections. I was saved on many occasions by Piasecki from Lublin, the block clerk who was shot later, and by Blockführer Mordarski, and other prisoners from the block’s permanent staff. They must have considered my seniority in the camp, my record of survival. Another reason must have been the fact that I tried to keep cheerful and talk to these people about “civilian” matters not connected with the camp, and maintained a sardonic attitude to the realities.

So they saved me, usually by putting me in with the dead – those who had died of “natural causes,” let’s say, or with the typhus cases – whenever there was an extermination of the block’s inhabitants. In general, typhus patients were not selected until they went into convalescence because the camp’s management was afraid of spreading typhus epidemics, and they wanted to protect the SS-staff.

Twice I experienced an especially strong, direct threat of being selected for the gas. The first time: the SDG entered the block unexpectedly and made sure that all the prisoners still alive went outside to the roll call square, which had already been walled off. Our numbers were put down. We were ordered to sit cross-legged. A sentry marched up and down in front of the top row.

A truck would be arriving any moment. I was in the middle of the third row. There were about 600 selected and registered for death. A heavy silence had set in. The prisoner next to me is Piotruś Sadowski, my old friend, sent here from the penal company. I whisper to him, “Piotruś, we’ll not get out of this one.” Piotruś replies in a Warsaw swagger, “Maybe not, but give it a try… .” Schreiber14 Piasecki comes out of the block; we get him to notice our whispering and gestures. He picks up a stick, like for beating someone, and starts making a terrible racket, “We must have order here, there’s no passage for the latrine stretchers! The middle must be clear!” He was deliberately creating havoc. Now we are close to the door of the block. “And you,” Piasecki issues an order, taking advantage of the sentry’s inattention – “get back to the block… for a second helping of soup!” After a while, our heartbeat’s back to normal. We hide under the fresh corpses…

The second time may serve as an example of the extraordinary humour that only the atmosphere of the waiting room to the gas could evoke. It was like this: the trucks had arrived and were being loaded up. The yard in front of the block was empty and the gate was closed. I got out of the hole I had been hiding in during the selection. There was a terrible silence all over the block, which had been crowded, full of noise, moaning and groaning just an hour before. There were only a few of us left. We had to do something! Have a smoke! I had a fag that I had bartered with some people from the camp through the block window.

There was a lot of soup in our block, too much for us to eat. The food was rationed for the number of prisoners at the roll call, so it included rations for those who would not need it any more – they had gone to the gas or died “of natural causes,” which happened more often here than in the main camp. We took a few drags on our newspaper-rolled shag. One of the male nurses, a Czech nicknamed Pepan, caught me at it. He had just come back to the block for something.

“You intellectual egghead (cor! what an insult!), you’re smoking, and we’re trying to save you, Muselmann. So, come along now to the gas.” He led me out through the gate. There were prisoners on the trucks already; the SS-men, Blockführers, and dogs were hurrying in the rest. Pepan left me at the gate and walked away smiling. The SS-man managing the transport points at me, shouts: “los, los,”15 and then points at the truck. Piasecki again ventures to save me. Pretending to give me a strong clout, he shouts, “Back to the block, you, you swine, get back to work!” and kicks me out of the gate. I do not think I will ever forget Pepan’s joke.

I will say this for Pepan. That macabre block had a simmering gallows humour, or should I rather say “gas humour” all of its own. A humour absolutely inaccessible and incomprehensible to normal people in normal conditions. I, for one, was also to blame. Just before the war, there was a fashionable tango beginning with the words “Life is an enchanted fairy tale when the girls love you…” and it went on “There is one girl, the one I love most of all.” We would sometimes sing a merry song to the tune of this tango, “There’s a gasworks where we’re all going, where we’ll all be meeting, perhaps tomorrow – who knows?...” Alas, it was the cruel truth.

Block 7, whose inmates kept changing all the time, was usually overcrowded. Almost always some prisoners had to sleep outside, on the crushed bricks, often lying in the mud. Especially the nights were creepy. At night people’s nervous condition was much worse than during the day. Besides, prisoners suffered more pain due to various diseases. Whenever I close my eyes, I can see a clear picture of one of those nights. Some prisoners in the block, are violently arguing over places in the upper bunks, a spoon, a belt, a pair of clogs, etc. The weakest are in the lower bunks with their heads on the bricks, i.e. on the floor. You can hear groans and curses all night long.

The roll call square would be cluttered up, too, with groaning and moaning, bickering over trifles, and conversations going on there as well. Only a few asleep. One night a certain episode filled me with horror. In the sharp moonlight you could see an aggravated mob in the square. It was a summer night in July; the moonlit human skeleton of a Muselmann tried to sit on the stretchers used as a latrine, but he was too weak and collapsed onto his companion, who sank in the excrement; another casually continued doing his business… I thought to myself that it could not be true, it was all a dream.

As I have already said, I spent as many as five months in the waiting room to the gas chamber. All the time the provisional occupants of the block came and went, so I met tens of thousands of people waiting for their death. Nonetheless, I think I could try to characterise the psychology and reactions of all the temporary lodgers of that death block. They could be grouped by attitude and reaction as follows:

1) the group of people who reconciled themselves to their fate, and even affirmed it – there was no hope, they thought, death was their liberation, so the quicker the better;

2) the group of people who refused to believe that they were doomed to the fate apportioned to them: it could not be, it was impossible, they said;

3) and finally, there were those who kept deluding themselves to the very last moment that they would manage to escape this predicament.

And it was precisely the handful of prisoners in this third group, people who believed in the impossible, in the unlikely, who managed to survive and leave Block 7 safe and sound. Of course, hope on its own was not enough; you had to take action, within the small and very unpromising potential you had to manage your conduct. You had to be an active Muselmann. And there were such individuals in the community of Muselmänner who are generally characterised as being completely apathetic, slow to react, and acquiescing to their fate with indifference.

Summer came and brought a rapid increase in the incidence of typhus. Rudek, a Block 7 male nurse, a well-built man in excellent physical shape, was finished off after only a few days. Healthy people with a strong constitution and normal weight were the ones who yielded to the wave of typhus most readily. Weaker constitutions proved to be stronger and more resilient. A seasoned Muselmann went through typhus and the period of convalescence after it with less trouble. He had a lower body temperature and needed a smaller liquid intake, subsequently making do with smaller food rations.

Bringing my memoirs to a close, I think that speaking about my life in Block 7 in Birkenau I need to devote some attention to its Blockführer, Wiktor Mordarski. When I was still in this block, I became curious about the moral problems related to the job of the Blockführer of this terrible place.

Speaking for the prosecution, you could charge Mordarski with taking the job in the first place, since as Blockführer he helped to set the extermination machine in motion. You could also accuse him that the people he saved within his modest means were first of all the Poles. For the defence, you could say that most of the official duties performed by prisoners, including those related to managing the camp hospital, places of selection and criminal experiments, also in some way helped the camp authorities conduct the extermination. But the struggle for power in the prisoners’ internal organisation conducted by the Reds against the Greens was surely right, and the victory of the Reds must have contributed to keeping the loss of life as low as possible.e

I have no courage to propose a solution to this dilemma. And believe me, not because Mordarski saved me from the gas bunkers on a number of occasions. It will be a permanent mystery to whom I owe being moved to the main camp of Auschwitz from that block, where it would have been impossible to avoid death. Was my transfer caused by an external intervention – family and friends, or thanks to the scheming of my mates in the camp?

Anyway, on 16 September 1942, I was unexpectedly moved back to Auschwitz’s main camp. An SS-man took me, clearly by force of habit, to Block 11.f However, he was pedantic and checked the delivery note, and after a while I found myself in the camp. My companions welcomed me as if I had come back from the dead. As they informed me, the hospital register of Block 28 said that officially I was dead. After a bath and being deloused, I could see how much Auschwitz had changed during my absence – I was moved; it almost felt like home… Of course, it was only 1942. I was to experience a lot more; many a time the hospital would be my refuge. But that would be a new stage in my Auschwitz knowledge of good and evil.

Translated from the original article: Gawalewicz A.: Poczekalnia do gazu. Fragmenty wspomnień muzułmana. Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1963.

Notes:

a. “Without anger and fondness”, objectively

b. Plural form of “Muselmann”

c. Block 11, the Death Block, where prisoners sentenced to death awaited execution or were gassed (before the gas chambers were built) or starved to death.

d. Translated by Mirosława Modrzewska and Peter Cochran, quote from: Poland’s Angry Romantic: Two Poems and a Play by Juliusz Słowacki. Balladyna, Grób Agamemnona, Beniowski. Translated by Peter Cochran, Bill Johnston, Mirosława Modrzewska, Catherine O’Neil, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009, p.279.

e. A reference to the political divisions among the Polish prisoners, the Reds being those who were card-carrying Communists or communist sympathisers, and Greens meaning others. This text was written under the Communist-controlled People’s Republic, so the assessment of the situation given in this passage need not necessarily have reflected the author’s true opinion of the situation.

f. Block 11 – Death Block (see above, comment 3).

References

1. Diarrhoea (inmates’ spelling).2. Work commandos, form up!

3. Zugang group – new arrivals, new prisoners.

4. Bauhof – construction site; Industriehof – industrial area: successive names for a precinct on the perimeter of Auschwitz main camp.

5. Totenmeldung – death record, a surrogate death certificate drawn up to report prisoners’ deaths.

6. Painkilling tablets.

7. Open the windows!

8. Woodyard

9. While running.

10. Caps off!

11.Wood gas.

12. Sanitätsdienstgrad, an orderly.

13. He died of typhus in the camp.

14. Clerical worker.

15. Get a move on!