Author

Dorota Lorska, MD, 1913–1965, Polish-Jewish physician, activist, and historian of medicine. Physician in a Republican field hospital during the Spanish Civil War, member of the French anti-Nazi resistance movement. An Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor (prisoner No. 52325), she was a prisoner doctor working in the notorious Block 10 and engaged in the international resistance movement in the camp. After the war she testified in the 1964 trial of Władysław Dering. For more information, see the extended biographical article in Medical Review Auschwitz online.

Block 10 is near the prisoners’ hospital in Auschwitz, next to Block 11 and opposite Block 21, and it is the place where SS physicians experimented on female prisoners. I was kept there for approximately a year and I had the opportunity to see for myself what was going on there and hear the other inmates’ stories about it.

Should we still be recalling those events now, twenty years after liberation? I was certain that this was the right thing to do, and the events of the last year have only confirmed me in my belief—that the truth about the darkest chapter in the history of medicine should be disseminated and made known to doctors and the public around the world. That’s why I have decided to give a short account of what went on in Block 10, even though it is not easy to go back to the memories of my experiences in Auschwitz. Some time in the future, I hope to expand on this topic, to preserve the memory of the SS physicians’ inhuman deeds and keep mankind vigilant.

In June 1943, I was arrested in Paris for my work in the resistance. After an investigation, the French collaborationist police handed me over to the Gestapo, and I arrived in Auschwitz in a transport from France on 2 August 1943. On the ramp I encountered an SS physician for the very first time. It was Dr Eduard Wirths, who was conducting the “selection1 for the camp” that day. First he ordered all the married women to step forward, and then selected a group of 100 from among them, including myself, and that is how I ended up in Block 10. At the time, there were about 400 Jewish women there, from ten different countries in Europe. They were all used as guinea pigs by SS physicians for their experiments.

That nightmare impression from my first days spent there—a mix of hell and a madhouse—is still haunting me now. It keeps resurfacing whenever I think of those times, and keeps coming back in my dreams—reminding me of that grim and bizarre reality.

After a couple of weeks, I fully understood what kind of “scientific research” SS physicians were conducting there, as well as the part played by other SS-men and inmates acting as their ancillary staff. Fortunately, during my first days in Block 10, I managed to establish contact with the in-camp resistance movement through a member of the disinfection kommando, a prisoner who was allowed to come into the women’s block.

Following the resistance’s instructions, I provided some concise though detailed reports on the experiments conducted on women, with a record especially of the names of the SS-men and other people involved in those experiments.

My report, the first ever description of what was going on inside the only women’s block in Auschwitz [main camp] at the time, was smuggled out of the camp by Tadeusz Hołuj and Stanisław Kłodziński in late 1943. In April 1964, we were pleased to learn that a precise abstract of that report reached London.2 It is among other reports from Auschwitz in the collection of World War II state documents preserved in the Polish Research Centre in London.3 In 1943, I wrote as follows:

Women prisoners in Block 10 are being experimented on by the following SS physicians: Prof. Carl Clauberg,4 Dr Horst Schumann,5 Dr Eduard Wirths,6 and Dr Bruno Weber. 7 Around 400 women are being kept in two large rooms in the block. The “used subjects” are regularly sent back to the women’s section in Birkenau, and replaced with “new subjects” selected from incoming transports. All of these SS physicians [personally] choose the women for their experiments. The largest group, around half of all the women, “belongs to” Clauberg. Clauberg and Schumann are the main experimenters and Block 10 is their research facility. Clauberg’s premises are on the ground floor, on the left, with a gynaecological surgery and an X-ray room. The experiment takes the following course: the selected married women have 10 ml of an opaque liquid injected into the cervix. After the injection, an X-ray is taken of their reproductive organs. The injections are repeated several times at intervals of a few weeks, and are always followed by an X-ray. The aim is to bring about an inflammation of the Fallopian tubes to block the passage to the ovaries and eventually cause infertility. The procedure is not always done by Clauberg himself, sometimes it is done by his ancillary SDGs.8 Dr Göbel,9 a chemist, collaborates with him as well. The injections are painful. They often cause peritoneal irritation and a fever, vomiting, and pain in the lower abdomen. These side effects occur more frequently when the injections are administered by an SDG rather than by Clauberg himself. The medical records are kept and X-rays are done by female orderlies trained by Clauberg himself. Most of them are Slovakians from the first transports, transferred from Birkenau, where Clauberg first began his experiments. I have not witnessed any fatal consequences [of those experiments]. Dr Horst Schumann is the second most important SS physician in Block 10. He “has” a group of about thirty girls aged between 16 and 19, who were deported from Thessaloniki.

Schumann X-rayed the girls in Birkenau. The next phase of the experiment awaited them in Block 10. Prior to my arrival, some of them were subjected to surgery and had one of their ovaries removed. In late September 1943, ten of those girls, some of whom had already been subjected to surgery, were taken to the operating theatre in Block 21, and were once again operated in the course of one afternoon. They all had their ovaries excised. The procedure was done by a prisoner, Dr Władysław Dering.10 The following night, one of the girls died of internal bleeding. The aim of Horst Schumann’s experiments is X-ray sterilisation. The ovaries are removed for a histological examination to observe the changes caused by the radiation.

Yet another group of test subjects comprises dozens of women who are being examined by SS physician Dr Eduard Wirths, using a German device known as a colposcope to examine and photograph their cervices. Dr Wirths has instructed his assistants to cut out specimens from their cervices and conduct a histological examination of them, for an early diagnosis of cervical cancer. The procedure causes profuse bleeding, though I have not seen any fatalities. The fourth group of experiments is being supervised by SS physician Dr Bruno Weber, head of the Hygiene-Institut11 commando. His experiments are based on determining the agglutination of red blood cells in persons with different blood types, and then determining the agglutination titre following the injection of a test subject with a blood sample of a different type. In addition, these women have 100-200 ml blood samples taken by SDGs. These specimens are later used in the research on the blood proteins conducted at the Raisko laboratory.

This summarises the facts I witnessed in Block 10 in 1943.

I can hardly keep myself from describing a particular situation connected with my report which caused a lot of tension. When fellow inmates asked me to write a report on the SS physicians’ experiments in Block 10, I compiled it one evening in the laboratory of the SS Hygiene Institute, after the block had been closed. The lab was under the command of SS Obersturmführer Weber. I wrote my report in a notebook just like the one I was using to record patients’ blood groups. The next day, I was in the lab with my friend, pharmacist Marta Malik, finishing the report. All concentration camp survivors know what Torwache means: an inmate on duty guarding the door. In theory, to prevent anyone from leaving the block, but in reality it was to warn us of the approaching SS-men. That morning Torwache failed—she did not notice or simply had no time to warn us of Obersturmführer Weber’s arrival. Suddenly, the door opened, and in came our boss, as softly and silently as a cat, accompanied by his inseparable Alsatian. We stood up and I recited the usual formula, “Zwei Häftlinge bei der Arbeit.”12 There was that notebook, right in front of us on the table, with all the notes on the SS experiments conducted in Block 10. Their layout and the summary directly implied that the notes were not a diary, but that they served a very specific purpose. Today, I can still remember that moment and all those thoughts rushing through my head. Weber took up the notebook, mindlessly flipped through its pages, clearly not noticing what they said. We were standing opposite the window looking out on Block 11.13 The window was blacked out with planks, but I knew that Death Wall was on the left and that’s where we would probably end up very soon. However, Weber just said, “Machen Sie weiter,”14 and left. Our knees were knocking in terror and it took us some time to get over it. Later on, the notebook was passed on in accordance with the previous arrangements. It ended up in good hands in Block 21, from where the pages with my report were smuggled out of the camp, to Kraków and, as it eventually turned out, reached London very soon.

During my time in Auschwitz Block 10, I also had the opportunity to watch the doings of Prof. Clauberg in the new Lagererweiterung (extension block), where the women of Block 10 were transferred in 1944. There was no doubt that this gynaecologist, so very well-known in the academic world, was devising artificial insemination experiments.

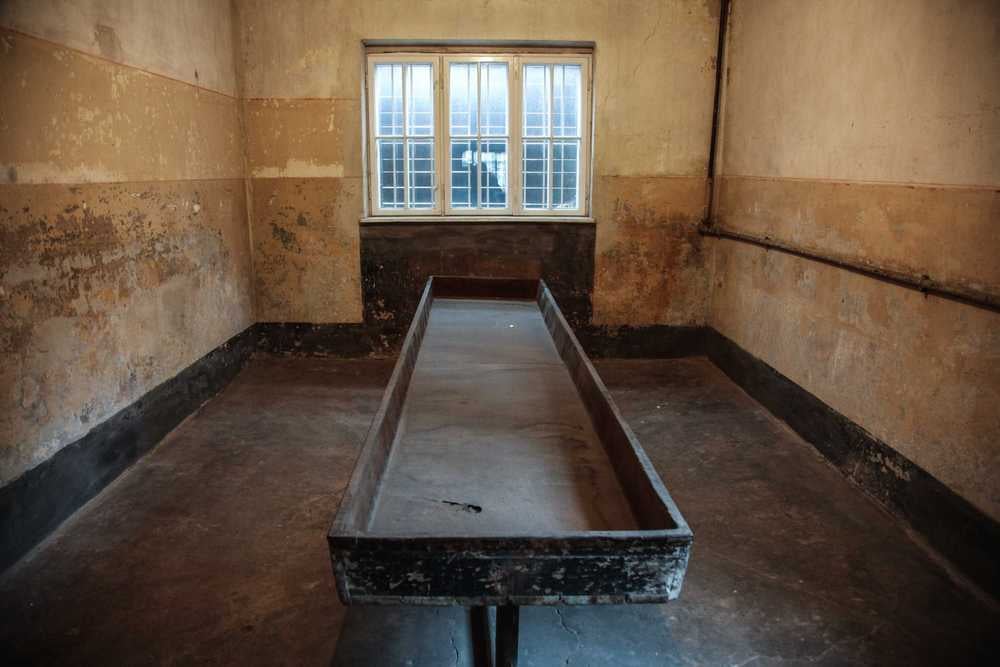

Interior of Block 10 in Auschwitz, present-day state. Photograph by Mateusz Kicka. Click the image to enlarge.

Those pseudo-scientific experiments conducted on the women of Block 10 can be defined and analysed even more precisely if we look at the documents discovered in the camp after its liberation, as well as the statements made by SS-men from the Auschwitz garrison on Prof. Clauberg’s and Dr Schumann’s experiments. We know that the aim of the female sterilisation project done with chemical substances, X-rays, or the surgical removal of the ovaries as tested on Jewish women in Block 10, was to develop methods for the sterilisation of entire nations or races—those the Third Reich denied the right to live.

The SS physicians were keeping up with the ideologists and lawmakers: Clauberg and Schumann were diligently working to develop the best possible methods for mass murder.

I recall that after liberation in 1945, Prof. Cuvier, a French gynaecologist, used the services of the French Auschwitz survivors to act as go-betweens and ask me to meet him. I visited him in Paris in 1945. He asked me very thoroughly what the Prof. Clauberg whom I knew from Block 10 looked like. Cuvier had known a Prof. Clauberg from Königsberg and met him several times before the War, at several gynaecological conventions. He had heard of his interesting research on the corpus luteum and wanted to know if the Clauberg I had met was the same person. My description matched his, though I was not sure whether Clauberg had been a professor in Königsberg before the War. Prof. Cuvier asked me detailed questions about Clauberg’s experiments in Block 10, apparently he was hoping that it was not the same person he had sat next to at those conventions and whom he considered an esteemed colleague. However, it soon became apparent that it was the same man—the professor and inventor once renowned in the world of science was the same man as the devoted servant of the Nazi German regime. He had offered his services in letters to Himmler, proclaiming he was close to achieving his aim. It was one and the same person, and his aim was to design a method which would let just a single doctor assisted by some ancillary staff sterilise hundreds or even thousands of women a day.

It is not difficult to imagine the atmosphere in which the prisoners detained in Block 10 lived. As the only women’s block in the men’s camp, it was effectively isolated off from the rest of the camp. The windows were barred and blacked out with wooden planks, so we had electric lights on all the time during the daylight hours. The immediate vicinity of Block 11, and hence our ability to hear and observe what went on there, aggravated our anxiety since we realised that besides the everyday hardships of all Auschwitz prisoners, we also had to endure the SS physicians’ experiments. You don’t have to be a psychologist to understand that apart from the regular torment experienced by inmates of a death camp, there was something more, something even more depressing for those kept in that block. One of the inexhaustible topics of our conversations was the “scientific” research of the SS doctors and the fear of what our bodies would be subjected to, before they were turned into ash to enrich the soil of Auschwitz.

I remember especially those young Greek girls who were experimented on by Schumann. They would huddle up on their bunks like startled animals, with an expression of fear and distrust in their (usually) beautiful eyes that had not had the time to experience the beauty of ordinary life to the full in Greece, the country they were born and raised in. The fact that they were kept in that block as guinea pigs could not but have the worst possible effect on their psyche. Just as in other parts of the camp, here too there were inmates who made our living conditions even worse by fighting, cussing, and stealing. The infamous SS system which allowed some prisoners to abuse others applied here as well. The arrival of political prisoners from France, including myself, marked a new chapter in the history of Block 10. Thanks to our contacts established with male inmates, including members of the camp resistance movement, we managed to replace some of the personnel of Block 10, and exert a good influence on the rest of its members. We received a lot of sympathy and aid from Ludwig Wörl,15 the Lagerältester (camp elder) at the time. He was a German communist who had been through all the German concentration camps since Hitler’s rise to power. The second person who helped us a lot, Hermann Langbein,16 was secretary to Dr Wirths, the chief SS physician. He was an Austrian veteran of the International Brigades which had fought in Spain. In a nutshell, everything that could be changed, improved in late 1943.

There were several talented women prisoners. Some genuine concerts, recitals, and dances were organised under the direction of Hadasa Lerner from Lwów. When we were left on our own in the block after it was closed up for the night, we would hear folk songs from various European countries besides the moaning, weeping, and gunshots. Hadasa Dédée’s hosting aroused interest and soon along with the laughs there were human feelings of mutual kindness and the will to help each other. We broke the ice enveloping our cold hearts in the wake of the inhuman environment and we prisoners would rediscover that it is normal to be friendly, that you do not have to be a wolf to one another, and that it’s better to be brothers.

To the best of my knowledge, a few dozen of the women who were detained in Block 10 in 1943–1945 are still alive today in various countries in and beyond Europe. Whenever they have the chance to meet somewhere around the world, they always recall those moments in Block 10 when those songs and the laughter helped them endure the hardships of the camp. But perhaps I might be wrong if I say that a few dozen of the Block 10 women survived. This year I had the opportunity to meet a group of survivors deported from Thessaloniki (victims of Dr Schumann and the prisoner-doctor Dering), while I was certain that they had not survived the camp. So perhaps there might be more survivors around the world that I am simply not aware of. The survivors also include the women doctors, those who were sent by the SS physicians to look after the patients in Block 10, like the Frenchwoman Dr Adélaïde Hautval,17 or Alina Brewda from Warsaw, who now lives in England; but also those who were sent to Block 10 individually or among the women’s transports: after some time they would be working in the laboratory of the Hygiene Institute, but living in Block 10, so they had the opportunity to learn of the pseudo-medical experiments and the way they worked. Apart from myself, there’s also Dr Helena Meizel living in Poland.

The attitudes of the prisoner doctors were a very important factor influencing the environment of the women inmates. First I will try to describe the options that the prisoner doctors generally had. Within the framework of the pseudo-medical experiments conducted in Block 10, besides their duty to look after patients, they had to take a stance on the question whether to help the SS physicians or even substitute for them in the performance of the experiments. They could refuse to collaborate in any way at all. They could refuse partially without making a flat refusal but declining participation in those practices which would harm patients. They could also follow SS instructions and conduct the procedures, and finally, they could follow those instructions very diligently. All these options could be observed in the conduct of the prisoner doctors working in Block 10. I will begin with the finest stance. The French doctor Adélaïde Hautval,18 the daughter of a Protestant minister, was arrested in April 1942, when she was trying to illegally cross the demarcation line between the free and the occupied part of France19 in connection with her mother’s death after she had been refused a permit. She ended up in prison with Jewish detainees. Dr Hautval was appalled at the way the Gestapo was treating those Jewish inmates and protested very strongly and openly. She was told that if she was a friend of the Jews, she would share their fate. She spent several months held in prison with Jewish women in France. In January 1943 she was deported to Auschwitz, with an armband which said “friend of the Jews” and carried a yellow star. She was transferred from Birkenau to Block 10. Dr Hautval refused to carry out Dr Wirths’ instructions and conduct colposcope examinations. She also refused to administer anaesthetics during procedures done by Dr Samuel, a German Jew who was a prisoner. She was summoned by Dr Wirths and ordered to explain herself. She had a particularly memorable exchange with him. When Wirths heard from Hautval that she refused to participate in the procedures because they were against her convictions, he asked her whether she had noticed that she was different from the Jewish inmates in Block 10. That was why he had sent her there, for her to appreciate that difference.

“There are many people in this camp that are different from me, take you, for a start,” Hautval replied.

I think Wirths must have been so astonished that he did not even think of punishing her for that retort. He only transferred her from Block 10, since her presence among the inmates there had not given him the results he had expected.

On innumerable occasions Dr Hautval followed the principles of ethics and humanity, and her attitude was the noblest example of how every doctor should behave. Of all the prisoner doctors working in Block 10, I would put Dr Dering at the opposite end of the scale. Dr Hautval was the paragon of a physician performing her duties and treating her work as a mission under any circumstances, even the most difficult ones. That extremely modest and upright woman had a very clear idea of what was going on in the camp. During my first days in Block 10, she was the one who told me everything about the SS physicians’ activities. She also explained that nothing would save us witnesses of their crimes, because the SS-men would never allow the world to learn of what they were capable of. Hence Hautval concluded that in the short period of our survival in the camp, we should treat other prisoners as humanely as possible. It must be emphasised that most of the prisoner doctors stood out from the majority of other inmates, and that with the exception of a few individuals, they behaved admirably. Many tried to help fellow inmates, ease their torment, often risking their own lives, which in any case was an everyday occurrence in the camp. Following the example of those prisoner doctors, the ancillary personnel, nurses, and clerks performed exemplary acts of bravery. I remember Jan Bandler, a young Czech medical student, who was working as a hospital clerk in Block 21. One day, when the SS physicians were testing various drugs on prisoners, Wirths summoned Bandler and ordered him to bring two inmates to be used as guinea pigs. Bandler returned after some time and told him that he had only found one prisoner. “Where is he?” Wirths asked. “It’s me,” Bandler replied. Wirths slapped Bandler on the face, but there were no further consequences for him.

There are numerous examples to show that a courageous attitude in defiance of the SS-men did more good to prisoners than servile fawning.

In the light of all of the above, there is no excuse for the attitude of Dr Dering and his kind—no justification, not even fear for their life should have driven those people to follow the SS physicians’ orders so diligently.

That brings me to the most topical problem regarding Block 10, namely the accountability of the prisoner doctors who excised the ovaries of those young girls who had been X-rayed. Let me brief those who do not follow the English press on a trial that deeply stirred London’s medical community in April 1964 (British Medical Journal, 16 May 1964, vol. 1, p. 1321). It is generally known that Dr Władysław Dering, who had performed many experimental surgeries on women, including those detained in Block 10, was not extradited from Britain to Poland when the Polish authorities demanded his extradition in 1947. In 1962, Dr Dering brought a libel case against Leon Uris, the author of the novel Exodus. In a chapter on Auschwitz, Uris wrote a sentence which said that Dr Dering conducted 17,000 experimental surgeries in Block 10 with no anaesthetics. The defendants, the publisher and the author himself, immediately rectified the information regarding the figure and the circumstances of the operations, now claiming that Dr Dering had indeed performed experimental surgeries on prisoners, but a smaller number of them and with the use of inadequate anaesthetics. So Uris was no longer libelling Dering. The proceedings went on for three weeks with many gripping episodes, and eventually changed from a case against the writer into a trial against Władysław Dering, who had violated the principles of medical ethics during his confinement in Auschwitz.

The witnesses for the defence were men and women—victims of Dr Dering’s 1943 experiments. They also included doctors from Poland, France, and England, as well as some British physicians summoned as court experts.

I am not going to elaborate on the reactions evoked by the testimonies made by the victims of the experiment. They persuaded the judge, jury, and the public that Dr Dering had acted with no remorse at all, and quite eagerly, because in this way he could show that he was deferential to the SS-men and expecting a reward, which he eventually received. In 1944, he was granted the dubious honour of being appointed Prof. Clauberg’s associate at his private clinic in Zabrze.20

As emphasised by Lord Gardiner,21 counsel for the defence, during the London trial Dr Dering showed absolutely no signs of remorse or regret for his shameful deeds. Characteristically, Justice Lawton,22 who did all in his power to hear and rule on the case as impartially as possible, on several occasions referred to Dr Dering as the defendant, even though he was the plaintiff. Summing up the case before the jury reached a verdict, Lawton stated that the following three facts had been ascertained during the proceedings:

- Dr Dering conducted at least 130 experimental surgeries on Jewish male and female prisoners used as guinea pigs in experiments for SS physicians, the aim of which was to enhance the procedures for the mass extermination of Jews and Slavs on German-occupied territories;

- Dr Dering conducted those surgeries willingly for two reasons: firstly, because he was an anti-Semite and had a different attitude to Jews than to other patients; and secondly, because he wanted to win the favour of the SS-men and eventually obtain a release from the camp;

- Dr Dering’s surgeries were conducted in a rough or even brutal manner.

Dr Dering’s argument, that he had excised ovaries and testicles which had been X-rayed for the good of his patients, was refuted by Sir Bryan Wideyer,23 professor of radiology at the University of London, who attested that in 1943 nobody thought that X-rays could cause cancer. Besides, by following this argumentation Dr Dering contradicted his claim that any refusal to obey SS orders could have earned him punishment, even a death sentence. If he had been acting for the patients’ good, he would not have obeyed SS orders; but if he had been acting under the threat of a potential penalty, he must have realised that what he was doing was wrong.

W[illiam] Nixon,24 a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Universities of Cambridge and London, enumerated the medical errors Dr Dering had committed, which he had discovered when he examined Dering’s victims and heard their stories and the testimonies given by prisoner doctor witnesses. Furthermore, when asked whether it was ethical to conduct medical experiments on humans without their consent, he said that over the past 2,400 years, all the doctors in England and in Europe had behaved in accordance with the Hippocratic Oath, and that they all used their medical knowledge and skills as best they could to help their patients, never to do them harm.

When asked a very specific question, how he would have behaved in Dr Dering’s situation, Prof. Nixon replied that if he had been forced to perform such an unnecessary and harmful surgery, the crime would have haunted him till the end of his days; and that he doubted whether he would have been able to continue to live afterwards.

Dr Dering won the libel case by the jury’s verdict, but the damages the jury awarded him amounted to a ha’penny.25 As someone quite rightly said, that was all that Dr Dering’s reputation was worth in the eyes of the jury.26

Although 21 years have passed since the events in Block 10, the integrity of the prisoner-doctors, as well as the accountability of the SS physicians and some of the prisoner-doctors, is still a question that has not been fully discussed in the medical press, though it certainly deserves more attention and discussion.

***

Translated from original article: Lorska, Dorota. “Blok X w Auschwitz.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1965.

Notes

- Wirths’ first name is mispelled (or Polonized) as “Edward” in the Polish article. Although our general policy in the English translation of articles from Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim is the faithful preservation of the original content and style including errors and spelling mistakes, we make an exception for the spelling of the proper names of well-known historical characters and events, making a translator’s note on the misspelling or misprint in the original Polish text. In the jargon of the German concentration camps, “selection” meant the selection of prisoners to be sent to their death.a

- Dr Lorska’s article was published in the Polish People’s Republic subject to Communist censorship. Her report must have reached the Polish government-in-exile, which was resident in London at the time. In 1943, following the Polish government’s reaction to the German discovery and disclosure of the Katyn Massacre committed by the Soviets in 1940, the Soviet government broke off relations with the Polish government, and hence the extremely reticent way in which this information is related in Lorska’s article. The fact that she only learned in 1964 that her report had “reached London” probably means that this was when she heard that it had been or was due to be published “in London,” i.e., in the Polish émigré press, perhaps in the monumental collection of wartime records compiled by the AK Polish resistance movement, which was instrumental in smuggling secret reports out of Auschwitz. By the 1960s, a group of Polish independent historians were working in London on the edition of these documents, which appeared in five volumes as Armia Krajowa w dokumentach 1939–1945, starting with Volume 1 in 1970.a

- The Polish name given in Lorska’s article for the institution is Polski Ośrodek Dokumentacji. In fact, the institution which published the collection of records Armia Krajowa w dokumentach 1939–1945 was Studium Polski Podziemnej (see Note 2).a

- For more on Carl Clauberg in English, see the following articles on this website: Czesław Głowacki, “Records of Carl Clauberg’s criminal experiments,” Stefan Kasperek, “Sterilisation on eugenic grounds,” and Stanisław Kłodziński, “X-ray sterilisarion and castration,” and the following articles published in successive proceedings volumes of the international conference Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire (2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022), all accessible on the Internet: Maria Cielsielska, “Experimental Block 10” (2018); Paul Weindling, “Pharmacological Procedures against Women during the Shoah: the Victims of Block 10 Auschwitz,” (2021); Hans-Joachim Lang, “Froukje Carolina de Leeuw (1916-2002): a female prisoner doctor's view of Block 10 in Auschwitz” (2021) and “The effectiveness of Carl Clauberg’s forced sterilizations. New findings from little-noticed original documents on the human experiments in Block 10 at Auschwitz” (2022); and Knut Ruyter, “Prosecuting evil. The case of Carl Clauberg: the mindset of a perpetrator and the resistance and procrastination of the judiciary in Germany, 1955–1957” (2022).a

- For more on Horst Schumann in English, see the following article on this website: Stanisław Kłodziński, “X-ray ‘sterilisation’ and castration in Auschwitz: Dr. Horst Schumann.”a

- For more on Eduard Wirths in English, see the following articles on this website: Zenon Drohocki, “Electric shock at Monowitz hospital;” Władysław Fejkiel, “The health service in Auschwitz main camp;” and the following articles published in successive proceedings volumes of the international conference Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire (2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022), all accessible on the Internet: Maria Ciesielska, “‘The corpse is still taking a stroll…’ The case of the German SS Doctor Johann Paul Kremer,” (2019); Helena Kubica,”Dr Mephisto of Auschwitz,” (2019); as well as the articles by Hans-Joachim Lang, Paul Weindling, and Knut Ruyter in the Conference Proceedings volumes listed above.a

- For more on Bruno Weber in English, see the following articles on this website: Stanisław Kłodziński, “The SS Institute of Hygiene laboratory, Auschwitz: Human Broth;” Jan Stanisław Olbrycht, “A Forensic Pathologist’s Wartime Experience in Poland under Nazi German Occupation and after Liberation in Matters Connected with the War;” and the articles by Maria Ciesielska and Hans-Joachim Lang in the conference proceedings volumes listed above in Note 4.a

- In a German concentration camp SDGs (Sanitätsdienstgrad) were SS assistant medical staff, usually male nurses.a

- Johannes Goebel (aka Göbel, 1891–1952) was an employee of the German pharmaceutical company Schering, “on loan” to Clauberg for his experiments at Auschwitz. After the War Goebel was a witness at the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Goebel See also Paul Weindling, “Pharmacological procedures against women during the Shoah: the victims of Block 10 in Auschwitz,” Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire. Conference Proceedings 2021, 4-9 October 2021, Kraków, Poland. Polish Institute for Evidence Based Medicine, 2021, 141-153. Online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358228728_Medical_Review_Auschwitz_Medicine_Behind_the_Barbed_Wire_2021.a

- Dr Władysław Dering (1903–1965), Auschwitz prisoner doctor and survivor, on orders of the camp’s authorities castrated male prisoners and sterilised women prisoners. For more details, see Maria Ciesielska, “„Operacje eksperymentalne były przyczyną mojego smutku i wstrętu…” Losy Władysława Deringa w świetle zachowanych dokumentów.” Ciemności kryją ziemię. Wybrane aspekty badań i nauczania o Holokauście. Martyna Grądzka-Rejak and Piotr Trojański (eds.), Dęblin: Lotnicza Akademia Wojskowa, 2019, p. 189-212, and Maria Ciesielska, “Władysław Dering i Jan Grabczyński – lekarze więźniowie w Auschwitz,” Nowa Medycyna 2019 (26: 2), p. 70-76.b

- Hauptsturmführer Dr Bruno Weber (1915–1956), German physician and bacteriologist, head of the SS Hygiene Institute (full German name: Hygiene Institut der Waffen SS Raisko O/S [Oberschlesien]. Raisko was a sub-camp situated about 2 miles away from the main camp of Auschwitz. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bruno_Weber_(doctor).a

- German for “Two prisoners at work.”a

- Block 11 was Death Block; the experiments on the women were done in the block neighbouring on the yard of Block 11, where the scheduled executions were carried out.a

- German for “Carry on.”a

- Ludwig Wörl (1906–1967; his first name is spelled in the Polish way in Lorska’s article). German male nurse and political prisoner of several Nazi German concentration camps; in Auschwitz he was Lagerälteste (camp elder) of the hospital barracks and protected numerous prisoners against SS violence. Awarded the Yad Vashem title of Righteous Among the Nations. https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/righteous-auschwitz/woerl.aspa

- Hermann Langbein (1912–1995; his first name is misspelled in the original Polish article), was an Austrian Communist resistance fighter against National Socialism. He fled Austria after the Anschluss to fight in the Spanish Civil War for the International Brigades, and was later interned in France and sent to German concentration camps after the fall of France in 1940; he arrived in Auschwitz in 1942, classified as a non-Jewish political prisoner (camp No. 60355) and assigned work as a hospital clerk. Langbein later used his concentration camp experience to help establish the International Auschwitz Committee and trials at which he testified. He was the author of several books on Auschwitz. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Langbein.a

- More information on Dr Hautval is available in English on this website in her biography by Ella Lingens, and also in “Experimental Block No.10 in Auschwitz,” by Maria Ciesielska, in Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine Behind the Barbed Wire. Conference Proceedings 2018, 9 May, Kraków, Poland: Medycyna Praktyczna Polski Instytut Evidence Based Medicine, 2019, 59–76. Online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344161872_Medical_Review_Auschwitz_-_Medicine_Behind_the_Barbed_Wire_Conference_Proceedings_2018.a

- See Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1964: 119-121.c

- After the fall of France and its occupation by Nazi Germany in June 1940, the French mainland territory was divided into a German occupation zone and a zone “ostensibly designated as free, governed by a new regime in the town of Vichy.” https://smithsonianassociates.org/ticketing/tickets/france-during-world-war-ii-occupation-and-resistancea

- Zabrze, the Polish name of this city, is the place-name that appears in the original Polish text of this article, though in 1944, when Clauberg was there, it would have been known by its German name, “Hindenburg.”a

- Gerald Austin Gardiner, Baron Gardiner (1900-1990), British judge and (later) Labour politician, Lord High Chancellor in Harold Wilson’s government. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_Gardiner,_Baron_Gardiner#Legal_career.a

- Sir Frederick Horace Lawton (1911-2001), British High Court Judge. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Lawton_(judge).a

- Sir Brian Windeyer (1904-1994; the name is misspelled in the Polish article), Professor of Therapeutic Radiology at Middlesex Hospital Medical School and Vice-Chancellor of the University of London, 1969-1972. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Windeyer.a

- William Charles Wallace Nixon (1903-1966), British obstetrician and gynaecologist, director of the obstetric unit at University College Hospital and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the University of London. He examined for the universities of London, Cambridge, Durham and Bristol. “In 1964, although a sick man, he acted as an expert witness at the trial of Dr Dering, accused of inhuman treatment of prisoners in the death camp at Auschwitz.” https://livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/client/en_GB/lives/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ASSET$002f0$002fSD_ASSET:378171/one?qu=%22rcs%3A+E005988%22&rt=false%7C%7C%7CIDENTIFIER%7C%7C%7CResource+Identifier.a

- A halfpenny, the smallest British coin at the time.a

- See also: Jerzy Rawicz, “Anty-Dering. (Działalność lekarza Władysława Deringa w obozie oświęcimskim).” Prawo i Życie, 1962, no. 13, pp. 8-7.c

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Maria Ciesielska, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; c—original Polish Editor’s notes.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

The contents of this site reflect the views held by the authors and do not constitute the official position of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.