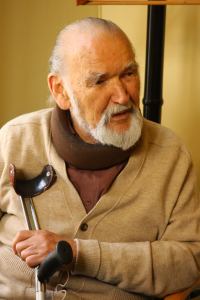

Photograph by Grzegorz Rosengarten

The exhibition “Memory Images: Labyrinths,” composed of Marian Kołodziej’s works, can be visited at the St. Maximilian Center in Harmęże after making a prior appointment by phone or mail.

CONTACT US

The Franciscan Monastery in Harmęże

Harmęże, ul. Franciszkańska 12

32-600 Oświęcim

phone: +48 33 843 07 11

e-mail: harmeze@franciszkanie.pl

www.harmeze.franciszkanie.pl

Read More

In the late 1990s an exhibition entitled “Klisze pamięci. Labirynty” (Memory Images: Labyrinths) was mounted on the lower floor of the Immaculate Conception Church at Harmęże. This church is part of the St. Maximilian Center, and the exhibition is a collection of drawings by Auschwitz survivor Marian Kołodziej (No. 432), who was sent to the camp in the first transport of prisoners. Apart from its unquestionable artistic value, the exhibition is also a testimonial. It presents an artist’s vision of the concentration camp hell, yet at the same time it highlights the heroic victory won in that hell by St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe.

After the War Marian Kołodziej graduated from the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts and made a career as a theater and film set designer. But he never mentioned what he went through in the concentration camp. After nearly half a century of silence he returned to that experience and created a shocking story about himself and those who died in the Death Factory. It was illness – a stroke followed by paralysis – that forced him to do this. He started drawing as part of his rehabilitation therapy. Drawing “Memory Images: Labyrinths” was a sort of selftherapy for Kołodziej, as he recalled.

He started working on “Memory Images: Labyrinths” in 1993 and finished in 2009, a few months before he died. In the sixteen years he created over 260 drawings of various sizes. He used the simplest means to tell his extraordinary, terrifying story.

The exhibition was officially opened on August 14, 1998. On that day the St. Maximilian Center at Harmęże, which is managed by Franciscans from the Kraków Province, became its permanent home. What prompted the choice? Because, as Kołodziej said in one of his interviews, “I was with Father Kolbe at that roll call.” At that roll call in late July 1941 St. Maximilian’s deed of disinterested love for a fellowprisoner he did not even know made a tremendous impression on Marian Kołodziej. St. Maximilian, Auschwitz number 16670, became the exhibition’s central character, alongside the artist. Over the 16 years Kołodziej’s penandpencil drawings gradually filled up the walls of the lower church at Harmęże. They are accompanied by props betokening the everyday realities of Auschwitz, which make up part of the installation. These small details – stones and broken glass – conjure up an exceptionally suggestive atmosphere, intensified by the silence prevailing in the subterranean church. Kołodziej uses symbols to tell the Auschwitz story. You will not see a German army uniform here, just two clashing worlds: the world of goodness (presented in human figures) versus the world of evil (presented in the form of beasts).

Wartime and the era of the concentration camps was an abnormal world, so Kołodziej depicts it in just two colors – black and white. But when he speaks of his pre1939 memories and his dreams, when he is thinking of the day of liberation, he uses a full color range – for the normal times.

In his exhibition he shows what the rejection of the Ten Commandments and the Christian values leads to, but he also uses the example of St. Maximilian to show that even in the inhuman conditions the Germans created in their concentration camps you could preserve your human dignity and win a moral victory.

Visitors are shaken at the sight of the broken glass panes next to the entrance to the exhibition. This arrangement is an attempt to answer the question on the personality of a concentration camp survivor after nearly sixty years since liberation. What is he like? – Broken, shattered!

Between 2003 and 2017 about 80 thousand visitors saw Kołodziej’s exhibition. “Memory Images: Labyrinths” employ the universal language of art, so they are an excellent teaching aid for young people, who make up the majority of the exhibition’s visitors.

Piotr Cuber, PhD, OFMConv