Author

Zdzisław Jan Ryn, MD, PhD, born 1938, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and formerly Head of the Department of Social Pathology at the Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków. Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the Kraków Medical Academy (1981–1984). Polish Ambassador to Chile and Bolivia (1991–1996) and Argentina (2007–2008). Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Physical Education (AWF) in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

The term Muselmann denotes a concentration camp prisoner in the state of utmost physical inanition and psychological exhaustion and is inseparably connected with the problems of concentration camps, particularly of camp prisoners. Paradoxically, this strange-sounding word derived from German became a general label for very many of the prisoners of Nazi German concentration camps, and entered into everyday use in the camps. With the crematorium chimneys smoking on the horizon, every prisoner knew very well what the term meant, regardless of the language they spoke. Its meaning was clear and absolutely unequivocal: it stood for the most wretched of the wretched, a prisoner described by linguist Stanisław Jagielski (1968) as “one who was teetering on the brink of death whilst still alive.”

Most Muselmänner [plural form of Muselmann] did not survive the camps, yet the tragic word for a prisoner on the verge of death survives in defiance of the concentration camps and has come down to us in its diverse versions in Polish, German and other languages. Muselmänner have received more attention in memoirs, novels, and short stories than in scholarship. There is a long‑standing need to put some order into the bibliography of the subject and define the characteristic features of this pathological syndrome. My basic aim in this article is to draw up an image of the Muselmann, his physical appearance, the causes of the condition, what he did and how he behaved in the various camp communities and, above all, his psychological condition.

The Muselmann’s existential state consisted of a specific set of physical and psychological symptoms, exceptional and unique from a medical perspective. In a wider sense it was a special pathological product of the system of extermination operating in the concentration camp. My examination of the Muselmann’s psychology gave me a unique opportunity for an insight into the experience of humans on the verge between life and death. Another of my aims was to familiarize the reader with this still little known, sometimes fascinating, always enticing if at first repulsive world.

Materials, sources, and methods

I analyzed survivors’ recollections of Muselmänner and various aspects of their condition. Their stories were collected by Dr Stanisław Kłodziński, an Auschwitz survivor himself, who sent out a specially compiled questionnaire to around 300 other Auschwitz survivors in the fall of 1981. He asked them for the origin of the German word Muselmann itself (Polish muzułman) and its synonyms in the concentration camp meaning, and the condition of the Muselmann (Polish muzułmaństwo). What physical and psychological features was a prisoner supposed to have to be considered a Muselmann? What were the causes of the condition, and what individual predispositions were required in a prisoner to develop it? How did Muselmänner behave and what were their habits? What was the attitude of other prisoners and camp overseers? Kłodziński’s respondents were also asked about the Muselmann’s susceptibility to, and immunity from, disease and the hardships of the camp, how Muselmänner died, whether it was possible for them to survive (if so, then how), and whether the condition left any permanent vestiges in survivors. By the end of June 1982 we had written answers from 66 men and 23 women. What we learned from the interviews we conducted with survivors at the Kraków Psychiatric Clinic helped us to understand and interpret the answers we had gotten to the questionnaire.

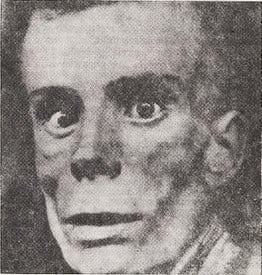

My second vital source of information were survivors’ memoirs preserved in the archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. I also used scientific publications and published memoirs, particularly those written by medical practitioners. I collected information from unique, generally very accessible sources such as photographs and drawings. For instance, I analyzed drawings by Jerzy Brandhuber, Władysław Siwek, and Jerzy Potrzebowski. The photographic portrait of a Muselmann on the jacket of the French album La déportation is deeply moving. Words can hardly do justice to the depth of meaning in this picture: perhaps only Gisges (1976) has come closest when saying, “Only their eyes shone like the eyes of wildcats.”

Muselmänner and starvation disease

The Muselmann condition is usually associated with starvation disease. Hunger is one of the inevitable outcomes of war, and was especially prevalent in concentration camps. In Poland, starvation left its mark most painfully on the inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto. A group of Jewish physicians and medical students cut off from the world in the ghetto created a unique book of worldwide interest on starvation disease, which they observed in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942 (Apfelbaum-Kowalski, 1946). Twenty-four of its co-authors perished in the ghetto, and only two lived to see the fruits of their work. They presented the results of their unique and tragic investigation in six chapters. The effects of starvation in the ghetto were extreme, as demonstrated by one woman, who was 152 cm (5 ft.) tall and weighed just 24 kg (53 lb.).

Jakub Frydman-Chlebowski (1946) gave a good description of the Muselmann’s psychological condition:

“His prevalent mood is indifference, with slow thinking, loss of memory, lack of interest in himself and his environment, slovenliness, diminished psychological activity and degradation. Patients don’t understand what’s being said to them. They’re slow to answer questions and prone to tearfulness. At a certain stage they get extremely irritable and impetuous, their thoughts are disorderly and confused, they get blackouts, delusions, and even terrifying psychoses.”

The picture of starvation disease in civilian populations or soldiers during the War was different from what was observed in concentration camps. The special character of the disease in the camps was determined by the specific living conditions and accumulation of traumatic experiences. These differences are described in detail by Urbański (1948), who examined around 2,500 survivors straight after the liberation of Auschwitz; he referred to this variety of starvation disease as “concentration camp inanition,” which was characterized by an invariant heart rate, with a curve parallel to the patient’s body temperature curve.

Sterkowicz (1971) defined the Muselmann condition as the fourth and final phase of starvation disease. It is characterized by behavior typical of patients suffering from anorexia nervosa – which you would have thought an absolute paradox given the situation – and the patient’s almost total insensibility to what is going on in his surroundings. Sterkowicz concluded that there was nothing that could please or perturb the Muselmann any longer. This phase was like a catatonic state (stupor), and in the camps it invariably ended in death.

One of the most notable medical studies on Auschwitz by a survivor is the work of Władysław Fajkiel (1976), most of which is on the Muselmänner he treated and observed in Block 28 of the camp’s hospital:

“They became irritable, quarrelsome, hysterical and grumpy, restive, and antisocial. Quarrels and moments of tension were usually brought about because of food. They accused each other of scrounging more food than their due portion . . . At this stage their feeling of hunger was most acute. They often salivated at the thought of food, which was always on their mind. . . . Food was a regular feature of their conversations. They promised themselves to lead a wiser life when they got back home – and eat several bowls of thick barley soup at a sitting, and several loaves of bread and butter with bacon and crackling. They would stay at home and help their wives with the cooking. The more imaginative ones kept notes, jotting down elaborate recipes for fancy foods and succulent titbits – an extravagant habit given the circumstances.

“A lawyer I knew had two thick bundles of recipes he had invented stashed away under his mattress. We found them after his death. He had scribbled them on scraps of cement bags, probably convinced he had made sensational discoveries in the culinary arts.

“Their torments caused by thinking and talking all day long about nothing but food were aggravated at night by corresponding dreams. Muselmänner dreamt of dinners in the homes of people known to entertain their guests lavishly, of good eats at smart places like the Polonia, the Bacchus, or Poller’s, or cozy provincial Jewish restaurants. Alas in their dreams, once the table was set, they had to wait for a latecomer, or at the last moment something was missing and the binge had to be postponed. Finally, when everything was ready and all they had to do was grab their knife and fork, the camp gong sounded. I was pestered by such dreams myself. . . . Once when I was in hospital . . . with starvation diarrhea I had a dream that I was in my mother’s cellar, bathing with a clowder of cats in a tub full of cream. I trembled at the thought that she might come in any moment. But the worst thing was that I was able to swim or even dive in the cream, but, somehow, I could not drink it. When I woke up I saw the face of a fellow-inmate in front of me . . . and that reminded me where I was.”

Replies to the questionnaire

The questionnaire received a good response. In addition to its informative value, it provided survivors with an opportunity to pay a tribute to the memory of their friends and nameless fellow-inmates who had died in the camp. For example:

“I’m writing out of affection and a sense of moral duty, because Muselmänner can no longer write down their stories. Their death was stripped of all respect and decorum . . . there was no drum-roll at their funeral, no birds sang as they were laid to rest, nor did the Man in the Moon shed tears for them . . . I think that even if we were never to learn the whole truth, yet for the rest of our lives we should keep searching for it in the stories of those who survived.” (T.O., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

The term Muselmann and its synonyms

To a reader unacquainted with publications on concentration camps the word Muselmann may seem strange and obscure. What does it mean and what is its origin?

The notion of Muselmänner was brought to Auschwitz by kapos from other camps and they used it to refer to debilitated prisoners who were inactive and negligent about their appearance. (J.O., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

The word came into the camp jargon from German. Yet some of the Polish prisoners didn’t like the German word and looked for equivalents in Polish, so various synonymous expressions were coined, meaning the same but etymologically covering a broader range. For instance, Polish words for cherub, foul, gawk, starveling, death, skeleton, wreck, slouch, fool, dolt, crawling four-footed animal, stinker, muff, louse, and beggar, along with words derived from German, such as szmuk (from German Schmuck used for slovenly women prisoners), kameln (German for camel, meaning hunch-backed), krypel (cripple), kretinerl (little cretin). More elaborate epithets included krypel figura and krematorium figura (Jagoda, Kłodziński, and Masłowski, 1981).

First used as a noun or a proper name, the word Muselmann and its Polish derivatives gave rise to verbs meaning “to become a Muselmann, to Muselmannize” viz. to lose a drastic amount of weight and become emaciated. Not surprisingly, the word attracted the attention of linguists like Witold Doroszewski. In a 1947 paper on the Polish spoken in concentration camps, Władysław Kuraszkiewicz wrote that the Muselmann was the very opposite of a smart prisoner. He was indifferent, stupefied, he had forfeited all his willpower, he could no longer control himself.

This is also the way survivors described the Muselmann:

“A Muselmann is someone at the end of his tether not only physically but also psychologically. He is no longer a human being, but a thing you can put in its place and it’ll stay there, something you can hit and it won’t react, something you can talk to but it finds it hard to understand what you want from it.” (Jerzy Mostowski, no. 17221, Memoirs Vol. 20, pp. 37–38 and 60, Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum).

The Muselmann was such a ubiquitous sight in the camp that you’d almost think it was normal. There were times when virtually all the prisoners lapsed into the Muselmann condition. But I won’t digress into the epidemiology of the phenomenon and its causes, because my focus here is on the psycho-physical aspects of the Muselmann.

Prisoners did not consider the Muselmann condition as a disease in the classic sense. It was more of a pathological state. You did not fall ill by being with a Muselmann, you simply became one yourself. The process is best reflected in the Polish derivative verb muzułmanieć – “to become a muzułman,” “to turn Muselmann.” The condition lasted for a time, generally weeks or months, depending on circumstances, and had various stages.

What the Muselmann looked like

The Muselmann’s physical appearance and how other prisoners saw him or her, the physical features that distinguished a Muselmann from other prisoners, and his behavior – these were the subjects of several accounts:

A Muselmann

“Gaunt skeletons clad in a bag of skin, with sunken eyes, a long nose, and a very thin, bony, face, ribs sticking out like hoops on a dry barrel, legs as thin as matchsticks bloated at the knees, sometimes swollen from feet to knees. The arms long, twisted and scrawny, thicker at the elbows and spade-like hands.

“The face had a sad, vacant expression; the lusterless eyes did not react to what was going around them. . . . Virtually no gestures to show their inner feelings. Muselmänner moved slowly. Someone compared them shuffling along in their clogs to a tired old nag plodding along the road

. . . Muselmänner used to slither along, swaying in a sitting or half-sitting posture. Their movement was monotonous, horrifying, resembling the way children in orphanages sway.”

(R.G., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

“Frequently I had the impression that they had turned into starving animals. A group of them looked strangely alike, as if they were siblings. When they walked naked from the hospital surgery to the washroom I felt I was watching a pathetic danse macabre.” (J.K., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

“It was terrible. Their skin was covered with louse bites and scratch marks. Dreadful and disgusting. There was an elderly man who looked tragically funny, his once ample belly was now just a fold of skin covering the genitals.” (W.B., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

The dominant features of the Muselmann’s face were his eyes, “heralds of death in the camp,” as Stanisław Pigoń put it (1966). The look in those eyes was devastating:

“The eyes of a concentration camp prisoner would have betrayed him even if he could have managed to escape, wash, and be fed and properly dressed, and at first glance seem normal. Those eyes were restless, staring in all directions and constantly on the lookout for fear of impending danger, or a chance to obtain things he needed; those eyes seemed to be popping out, glowing with a strange phosphorescence like the eyes of a wolf, glowing with hunger. Yet at the same time the look in those eyes was alert, lively, taking in everything around. The Muselmann’s eyes were restless, but they stirred only for one thing: where to obtain food. The look in those eyes was apathetic, sunken under the eyelids, shining green, they seemed dead already, showing not a will to live, but a blind and vacuous hunger.” (M. J., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

“Just their eyes. Large, goggling, flashing. The life that was oozing away cowered in the eyes, clinging to the dying body in its eyes and making them unnaturally big.” (A.S., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

A Muselmann

“Their posture was bent, stiff, they moved swaying, slightly reeling, they put out their elbows to keep a balance, their steps were short and shaky. They liked to lie curled up, and wrapped their blanket round their head. . . . Their faces were covered with stubble, like the faces of old men. Their noses became as sharp as a knife-blade. Being a Muselmann brought on old age. It made twenty‑year‑olds look senile.

“A Muselmann’s voice was unnatural, shrill, aggressive or plaintive, tremulous, he spoke slowly.” (M.J., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

“Wherever he was standing, a Muselmann moved his shoulders rhythmically, as if to make himself warm. Often two of them would stand back to back, rubbing each other.” (J.L., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

“They rubbed each other, in what was called the dance of the Muselmänner.” (A.A., K reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

“A Muselmann was recognized not only by his typical appearance but also by the way he behaved. This was determined by his psychological condition rather than by any external influence. His perceptiveness and sensitivity to external stimuli was severely curtailed, which exposed them to persecution on the part of camp overseers. They often behaved in an unexpected way; their reactions were surprising, not right in the situation. Hunger broke them down, warped their mind, deprived them of humanity. Neither spiritual nor rational arguments got through to them. Neither faith nor intelligence could stop their way downhill. . . . An individual known to have been outstanding, patriotic, a soldier, a professor, a social worker – suddenly transmogrified into a totally different creature, deaf and blind, insensible, apathetic, responding only to the sight of food.” (M.J., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

Sometimes Muselmänner could be seen in small groups. They gave the impression of a group merely in the physical sense, standing together but usually in silence. We know little of what went on between them, their mutual relations, or what they talked about, what constituted the basis of the group ties that must have existed between them.

“If they happened to utter a word, it usually reflected their basic needs – “a drink,” “give me…,” “can’t,” “sit down,” “don’t want to,” and emotional states – “mother,” “sister,” “it hurts here,” “they beat me up,” “they…,” etc.” (M.C., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire).

The psychological state of Muselmänner

Survivors’ replies to the questionnaire shed some light on the psychological makeup of the Muselmann. As Muselmannization advanced, the victim’s vital and psychological energy dwindled down. After a period of fear and dread his entire psychophysical constitution broke down – gradually or suddenly. The end result was total indifference to the world around him, with a selective sensitivity persisting only to food-related stimuli. All his other defensive mechanisms had expired.

“As a rule Muselmänner were withdrawn and truculent. When asked a question they would answer in monosyllables or mutter something.” (W.T., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“Sometimes they gave the impression of no longer being alive. They didn’t care about their appearance, they were filthy and smelly. They did not listen to friendly advice, on the contrary, they always suspected people of malicious intentions.” (E.B., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

Their cognitive functions, mainly their perception, but also their memory and thinking, went down dramatically. In some cases the damage to their intellectual capacity was as bad as in a psycho-organic syndrome:

“A Muselmann could not collect his thoughts, his memory was so poor that he could not even remember his name.” (Michał Dziadek, No. 121235, Memoirs Vol. 87, p. 122, Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum)

“My psychological state was even worse. . . . I was not able to add up three simple numbers in my head; if, after a tremendous effort, I managed to add two of them together, I would forget the third; when I remembered the third I could not remember the sum of the first two. When I found a scrap of newspaper I tried to read it, but my attempt failed; the letters jumped up before my eyes and I could not put even a single word together. It was particularly tragic for me that I forgot my father’s name and, despite my efforts, I could not recollect it.” (J.C., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“How did a Muselmann speak? In a special kind of jargon, I think, chaotically repeating the same thing over and over. He left his sentences unfinished, suddenly broken off, illogical.” (R.G., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“Alongside other symptoms, there was a strange feeling of somatic dissociation. There were moments when I wondered whether my hands or other parts of my body were indeed mine or not. My movements were slower and slower and sort of beyond my control.” (M.C., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

One of the most conspicuous features in the behavior of Muselmänner was their passivity and submissiveness. They let themselves be brutally treated, beaten up and bullied without putting up the slightest resistance. Even the most painful traumas did not evoke any defensive reflexes, they did not result in any natural reaction, neither avoidance nor attack. In this respect, they resembled patients with hypokinetic catatonia.

Experiencing hunger

Muselmänner were the prisoners who were the most severely affected by hunger, which was of course prevalent in concentration camps. Their predicament was inherently linked with starvation and the torment of hunger. There was a direct correlation between being a Muselmann and hunger. Malnutrition, hunger, and being a Muselmann were a cause‑and‑effect shortcut on the road to death in the camp. Not surprisingly, hunger drove prisoners to commit deeds that were obviously at odds with their personalities. Hunger released aggression and often led to moral degradation and total violation of the principles of ethics. Hunger sometimes impelled prisoners to acts normally regarded as criminal.

The psychopathology of hunger, one of the axial problems in the Muselmann experience, could trigger a catastrophic sequence of traumatic events.

“Hunger was a dreadful overlord.” (A.M., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“At that time I weighed around 40 kg [88 lb.], and the overwhelming feeling that tortured me was hunger, hunger such as I had never known before. I felt an uncontrollable craving to get hold of the wooden board of the bunk and start biting and chewing it to appease my hunger. I had never been so hungry.” (J.S., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

Muselmann survivors

Let’s now consider those who survived the Muselmann condition. Despite the critical state in which they were at the time, they remembered what they had been through. What is striking is the disparity between their perceptual capacity and the seriousness of the psychological disturbance. Even when they were in the Muselmann condition and seemed to be completely cut off from their surroundings, they still had a perception of themselves and others. They processed the information that reached them from the outside world in a different way, and often they behaved in a way that was quite unexpected, against their will, as if to spite life.

A Muselmann after camp liberation

“All the affairs of the world seemed unimportant. The physiological functions ceased to matter. Even hunger no longer troubled me. I had a strange feeling of sweet well‑being, only I did not have any strength left.” (W.B., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“Those who did not go through the Muselmann state have no idea of the psychological transformation the Muselmann underwent. He didn’t care at all about his future prospects, so much so that he put up with anything, and just waited for a peaceful death. He neither wanted nor had the strength to fight for his life.” (K.T., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“I was overcome by general apathy . . . nothing interested me and I did not react to external stimuli, I did not wash even when I had the chance, I did not even feel hungry. I lived in a sort of dream. I owe it entirely to my friends that I recovered from it. . . . They got some water, stripped and washed me. Right then something happened to me, it was like an electric shock. I became a normal prisoner again and wanted to survive at any cost.” (F.F., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

“I got dizzy at the thought of food and drink, and thought I would fall. At the time, I would have been willing to die, just to eat and drink my fill before I died. . . . For 20 years after the War I weighed 45 kg [99 lb.] in my clothes. Often I have nightmares about the camp, I dream I’m “organizing” some food, being tortured, running away in complicated circumstances, and then I wake up exhausted. . . . I still binge on bread and potatoes, which there was never enough of in the camp.” (J. W., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

Female Muselmänner

One of the respondents to the questionnaire said that women prisoners found it even harder than men to keep themselves from gobbling up the whole contents of a food parcel in one go. The temptation was stronger than the value of life, she wrote. In comparison with men, female Muselmänner behaved with more of a show; they tended to display their aggressive feelings to one another more readily than the men did, and in spite of their serious condition, they could still be flirtatious.

“They spoke faster and louder, they were hysterical and noisy . . . they still smiled even though they were very sad . . . Apart from this, there was not much difference between the way men and women went through the condition, its course was similar, and the effect of treatment the same.” (J. W., reply to Kłodziński’s questionnaire)

Death and dying

Prisoners in an advanced Muselmann condition were suspended between life and death; the signs of life, especially the psychological ones, were dying out in them. That’s why the true Muselmänner have never spoken out. Generally they died quietly, as if in their sleep, they might only have shown a defensive reflex when someone went “to get a syringe.” Even Muselmänner were terrified of having the deadly needle jabbed into their heart. The opinion seems to prevail that Muselmänner were so overwhelmed by exhaustion and indifference that they were not capable of committing suicide, although suicidal thoughts oppressed them and they might have intended to kill themselves. Instances of suicide occurred only in the initial phase of Muselmannization, when a prisoner’s physical condition could still help him or her accomplish a suicide attempt.

Other prisoners’ attitudes to Muselmänner

Muselmänner made up a separate class within the camp community, and they were on the bottom rung of the social ladder. Although still alive, they were treated as if they were already dead. Not only camp overseers but prisoners as well treated them like inanimate things. Muselmänner were useless, not needed at all, they were a hindrance and a general nuisance. Their indifference and erroneous perceptions of their environment led to their total alienation from the community of prisoners. They led their wretched existence in the background, left to their lucky or, more often, unlucky fate. All their defensive reflexes had expired; they were almost asking the kapos to beat them up. Instead of defending themselves, they were surprised and seemed not to understand the situation. The first reaction evoked by their appearance, posture, filth, and stink was disgust, repugnance, and irritation. Such was the general attitude of other prisoners to Muselmänner. Yet fellow-prisoners did not consider them mentally ill.

The stigma of Muselmannism

“We are still stuck in the camp, although nobody seems to notice this” (T.J., Kłodziński’s questionnaire). This simple statement by a survivor encapsulates the truth about the progressive character of the long-term pathological effects of incarceration in a concentration camp. The image of the Muselmann has been preserved as well; the individual experience of being or becoming a Muselmann, and above all the trauma of hunger and fear of extreme food shortage have persisted in ex-Muselmänner. It recurs in various forms: fits, a feeling of insatiable hunger, binging, a morbid anxiety about food shortage, habitual hoarding, especially of scraps of bread, and nightmares about hunger and its appeasement. Residual pathological consequences are as diversified as were the concentration camp Muselmänner.

Final remarks

I found it difficult to understand everything survivors said about Muselmänner, and of course about themselves. After all, their stories represent only a fragment of what they went through in the camps, a tiny part of their suffering. It is difficult to find the right words to make generalizations, and it is even more difficult to formulate evaluations.

Viewed as a specific pathological condition, Muselmannization was a product of the concentration camp death factory. If a young and healthy individual did not soon die in the camp in other circumstances, he or she was subjected to the destructive factors that led to Muselmannization. The death factory worked efficiently and effectively to implement its warped, inhuman ideology. The human raw material was supplied in successive consignments to its machinery and conveyor belt. At the ramp it was sorted; the less useful were eliminated at once, and “better” material moved on for further processing. The final product was cast in the Muselmann mold. Thousands, tens and hundreds of thousands of Muselmänner were manufactured – human wrecks stricken with a death wish, four‑footed animals, crawling about and gawkish. They were shuttled along on the conveyor belt, one resembling another, number after number, item after item. Once the Muselmann cooled down in his mold his life was over, he was ready for dispatch from the death factory, through the chimneys of the crematorium.

All that seems to be left of all those victims is just the dust and ashes blown over the fields around Auschwitz. But what happened to their psychological energy? What form did their slaughtered emotions, desires, and thoughts take? What was the sense of their suffering and death? It could not have all disappeared completely and without a trace.

The suffering and death of every prisoner in the camp generated responses and attitudes as had never been encountered in humans before. There were many of these responses, though we know only of a few. The heroic response of Father Maximilian Kolbe re‑humanized the life of people in a place as inhuman as Auschwitz, as Cardinal Karol Wojtyła (later Pope John Paul II) observed. The Kolbe response still excites and inspires humankind today, revealing the dimensions of human potential even in the face of death and in death itself. Questions about the sense of suffering and death are like questions about the sense of life. As Frankl has written (1971), the account of the suffering human will only be settled in transcendence; it cannot be cleared in the immanent world.

Father Konrad Szweda, a respondent to Kłodzinski’s questionnaire, said,

“The Muselmann . . . tipped the concentration camp scales in favor of love over and above hatred. Spiritually richer than their powerful overseer with whip in hand and hobnailed boot, these half-dead creatures swarming over the camp were like a ray of light in the darkness.”

Paradoxically, survivors still carry the camp reality in themselves, along with the conviction and awareness that many better and worthier people did not survive. In the words of Viktor Frankl, Mankind felt that he was at the mercy of fate, because he used to think that he had reached the limits of suffering, but suddenly he found that suffering was a bottomless pit, that there was no absolute limit to suffering. That one could always suffer more...

Translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1983.

References

1. Apfelbaum-Kowalski, E.A. (Ed.). Choroba głodowa. Badania kliniczne nad głodem, wykonane w getcie warszawskim w roku 1942. Warszawa: American Joint Distribution Committee; 1946.2. Doroszewski, W. “O wyrazie muzułman.” Rozmowy o języku. 1948;4: 85–92.

3. Fejkiel, W. “Głód w Oświęcimiu.” In Wspomnienia więźniów obozu oświęcimskiego. Oświęcim: Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz–Birkenau; 1976: 61–68.

4. Frankl, V. E. Homo patiens. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy PAX; 1971: 83.

5. Frydman-Chlebowski, J. “Charłactwo z niedożywienia.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1946: 9–11 and 235–251.

6. Gisges, J. M. “Stacja płonącej nocy.” In Wspomnienia więźniów obozu oświęcimskiego. Oświęcim: Auschwitz–Birkenau State Museum; 1976: 261.

7. Jagielski, S. “Psychiczne galwanizowanie muzułmana.” Przegląd Lekarski–Oświęcim. 1968: 106–109 .

8. Jagoda, Z., S. Kłodziński, and J. Masłowski. “Osobliwości słownictwa w oświęcimskim szpitalu obozowym.” Przegląd Lekarski–Oświęcim. 1972: 34–45.

9. Kuraszkiewicz, W. Język polski w obozie koncentracyjnym. Lublin: Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski; 1947: 122–123.

10. Pigoń, S. “Wspominki z obozu w Sachsenhausen (1939-1940).” Przegląd Lekarski–Oświęcim. 1966: 156–157.

11. Sterkowicz, S. “Uwagi o obozowym wyniszczeniu głodowym.” Przegląd Lekarski–Oświęcim. 1971: 17–21.

12. Urbański, B. “Własne spostrzeżenia nad chorobą głodową więźniów oświęcimskich.” In Pamiętnik XIV Zjazdu Towarzystwa Internistów Polskich we Wrocławiu w r. 1947. Wrocław: Polskie Towarzystwo Lekarskie; 1948: 375–379.