Authors

Julian Gątarski, MD, 1922–1982, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy.

Maria Orwid, MD, PhD, 1930–2009, Professor of Psychiatry, Director of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków. Survivor of the Przemyśl ghetto.

Małgorzata Dominik, MD, 1941–1979, psychiatrist, Chair of Psychiatry, Kraków Medical Academy.

The results presented in this work are one further attempt at a psychopathological analysis of the psychological state of former Auschwitz-Birkenau prisoners. Investigations of this type have already been carried out in the Department of Adult Psychiatry at the Medical Academy in Kraków for ten years. In contrast to the previously examined group of 100 persons (Leśniak, 1965; Orwid, 1964; Szymusik, 1964) where the members of the group had been chosen randomly, all the subjects of the examination described here were the victims of different criminal pseudo‑medical experiments that had been performed in the camp.

In the years 1966-1968, 91 men aged 42‑68 years (average 53.2) and 39 women aged 41‑69 years (average 53.7) were examined. At the time of the examination, 23 persons had elementary, 63 secondary, and 44 higher education.

Regarding marital status, 104 persons were married, eight were single, 11 were widowers, and five were divorced. The average age at the time of imprisonment was 27.2 years for women and 20.4 years in case of men. The average period spent in the camp was 3.2 years for women and 3 years for men. Although men were usually isolated for 4‑4.5 years, their average period of imprisonment was shorter because in certain cases prisoners were released earlier.

Experiments performed in the camp were highly traumatic for the prisoners and caused additional psychological and physical breakdowns. Similar observations were made by Dąbrowski and co‑authors (1965).

Psychiatric examinations carried out in the Department of Adult Psychiatry in Kraków resulted in the diagnoses of psycho‑organic syndromes in 59 men and 28 women, depressive syndromes in 41 men and 32 women, and personality disturbances in 82 men and 32 women. Almost all the subjects exhibited more than one syndrome of psychopathological or social disorders. All the examined subjects suffered from at least one of the disorders mentioned above.

The former prisoners classified into the first group demonstrated a wide range of disorders that are referred to as psycho‑organic syndromes.

Disorders of this type have already been described in Polish literature by Szymusik (1964), and by Półtawska and co‑authors (1966). Affective‑impulsive disorders in the form of impulsiveness, irritability, affective instability, dysphoric states, defective memory, and the inability to concentrate, causing great difficulties in work and education, have always been emphasised.

Many subjects exhibited states of consciousness distortions usually lasting no longer than several seconds. The subjects, especially those who were imprisoned in their childhood, became easily tired and suffered from symptoms of premature ageing. All the subjects complained of general bad moods, such ailments as headaches, dizziness, buzzing in the ears, body balance disturbance, poor sight and hearing, and the feeling of permanent exhaustion.

States of depression (the second group) comprised symptoms ranging from neurotic disorders to syndromes of depression‑anxiety, which resulted in a worse frame of mind, a sense of being useless, inefficient, and uncertain, an inability to plan the future, as well as in recollections of traumatic experiences from the camp period. Symptoms of depression were frequently hyper‑compensated for by excessive activity or happiness, and were easily transformed into depressive decompensation. The latter symptom was most frequently observed in the group of examined women.

Symptoms of depression were accompanied by a permanent feeling of fear. The real danger (from the camp period) was substituted by an abstract danger, as Kępiński (1966) observed. The feeling of fear had various forms and shades, from a sense of general danger and conviction that something bad would happen, through anxiety reactions that appeared in even quite easy situations, to a feeling of fear of everything that might be associated with the camp, such as uniforms, hospitals, any sign of violence, crowds, or raised voices.

The psychopathological syndromes are consistent with those described by Szymusik (1964). We can also support his claim about a certain similarity of clinical manifestations among the former prisoners.

The third group, including personality changes and adjustment difficulties, comprised the greatest number of subjects (82 men and 32 women). Their pre‑camp profiles were usually uniform. Almost all of them had been active, energetic, and sociable, with clear ideological‑moral attitudes. It may be assumed that these features most probably predisposed them to activities in the underground movement and constituted one of the basic elements that enabled them to survive the camp. This observation was supported by the conclusions drawn by Teutsch (1964). The striking uniformity of the pre‑camp psychological profiles in this group was also observed by Dąbrowski (1965).

Entrance into the Auschwitz main camp (27 January 1945)

When he compared the survival of the camp to the after‑effects of psychosis, Kępiński (1964) concluded that former prisoners became entirely different people after their isolation in the camp. Venzlaff (1958) also claimed that the camp experiences might lead to long‑lasting irreversible personality disorders.

The following features are dominant in the picture of the post‑camp personality disorders: change of basic, general frame of mind towards depression; a lack of confidence in other people; suspiciousness; irritability; explosiveness; difficulties in establishing interpersonal contact; frequent cases of missionary attitude, etc. Leśniak (1965), before other Polish authors, distinguished three basic directions of personality changes in the former prisoners: depression, suspiciousness, and explosiveness. He also compared post‑camp personality changes to those that could be observed after certain psychological disorders and he posed the question whether the three types of personality changes mentioned above might be equivalent to general types of changes in life after experiences that “exceeded the limits of human endurance.”

The situation of prisoners after liberation might be compared to the situation of people described by Kroeber (1957) who were forced to develop or re‑develop their own model of life (“re‑adjustment”) and find new groups of reference (Merton, 1965).

It turned out that the majority of former prisoners, the subjects of our examinations, still lived in the circle of values from the camp period, which had become the main range of reference in estimating people or events, or creating a hierarchy of values. In the majority of cases the subjects had not been able to develop new ranges of reference for their normal everyday life. They felt alienated among people who had never experienced concentration camp life, they knew they were not being understood, they were convinced they were different, inadequate, strange, useless. Sometimes they assumed an attitude of superiority or inferiority towards others. Their range of reference was formed by a closed period in their life: their concentration camp experiences (Orwid, 1964).

The majority of the examined subjects felt very closely related to their former camp mates; usually such people were their closest friends and they were able to feel well only in their company. A number of the examined group, however, avoided the company of their former fellow prisoners because such meetings intensified their anxiety, sense of danger, or somatic ailments. There were no subjects who remained indifferent towards their camp mates. All subjects had or still have nightmares about the camp.

The hypothesis (Orwid, 1964; Teutsch, 1964) that their post‑camp adjustment to life was worse than the adjustment to life in the camp under the conditions of the strongest possible bio‑psychological stress was once again confirmed when the former prisoners were examined in the Department of Adult Psychiatry at the Medical Academy in Kraków This, however, seemed only natural considering the fact that the examined group consisted of people who were forced to completely concentrate their entire strength during their imprisonment. Psychopathological and social phenomena that can now be observed in them are the after‑effects of such a concentration in extremely difficult conditions that exceeded the limits of endurance of almost all prisoners.

The same group of 130 persons was also subject to electroencephalographic examinations, which were carried out with the help of a 15‑channel appliance produced by Alvar. Bipolar surface leads, unipolar leads and triangulation leads of the so‑called deep triangles were used in the examinations. Activation trials were performed in all cases with three‑minute hyperventilation and three‑minute flash exposition (stroboscope). Stoppage reaction and the rhythm of leading were also taken into consideration.

The results of the electroencephalographic examinations were divided into normal, flat, and pathological records. Due to interpretation difficulties caused by the lack of anamnestic data, flat records were put into the group of normal records. Pathological records were divided into three groups: generalised pathological records, focal pathological records, and paroxysmal pathological records.

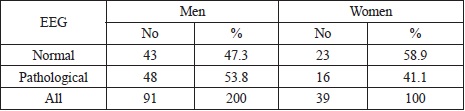

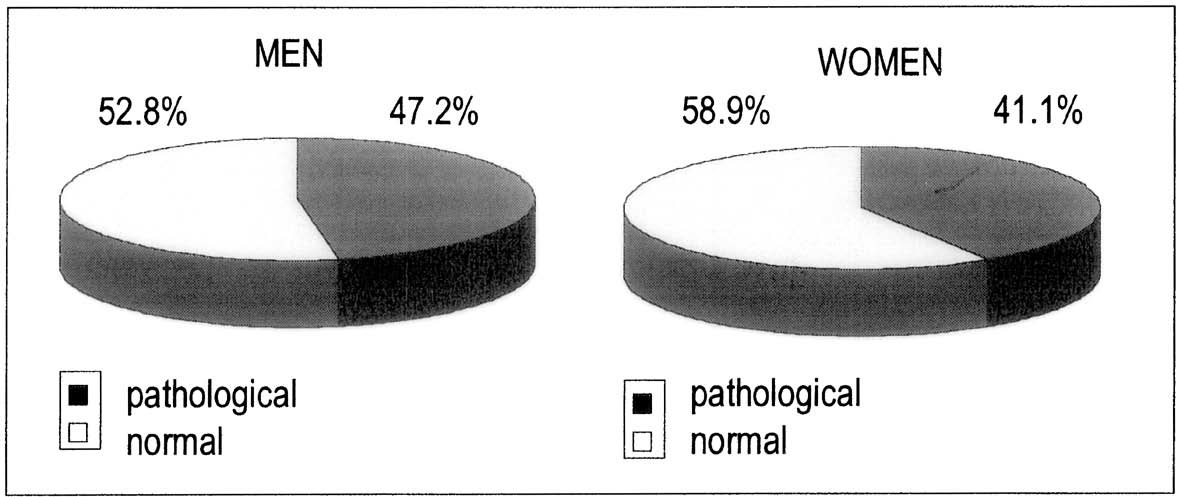

Table I shows the correlation between the total number of normal and pathological records. Records that were specified as normal, as well as 17 flat records, could be observed in 43 men (47.2%); 23 normal records, including 12 flat records, were recorded in the group of women (58.9%). There were 48 pathological records observed in men (52.8%) and 16 in women (41.1%).

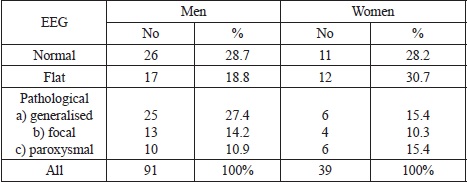

Table II illustrates the quantitative and percentage correlation of normal and pathological records with the division of pathological features into generalised, focal, and paroxysmal changes. There were 25 pathological records with generalised pathology features in the form of scattered slow elements (theta and delta waves) in men (27.4%) and 6 in women (15.4%); focal pathology features in the form of focally localised elements of slow acute single‑phase and two‑phase waves were found in 13 men (14.2%) and in 4 women (10.3%); paroxysmal discharge features in the form of acute single‑phase and two‑phase waves, slow elements or spike-and-wave complexes were observed in 10 men (10.9%) and 6 women (15.4%).

Table I: Results of electroencephalographic examination

Table II: Types of electroencephalographic records

It should be emphasised that the group of subjects with psycho‑organic symptoms diagnosed during psychiatric examinations exhibited a great number of pathological features in their bioelectric records. In the group of men, pathological features in EEG records could be observed in 78.5% of the cases and among the women in 71.9%. Pathological changes were largely of a diffused character. A majority of left‑sided focal changes could be observed. Among the members of this group, intensified slow activity was recorded in nine cases after hyperventilation. Stroboscopes caused the intensification or development of paroxysmal discharges in seven subjects.

Figure 1: Percent of pathological electroencephalographic records in the examined group of former prisoners (with respect to sex)

The stoppage reaction was absent in 32 cases in this group. “Leading” could not be observed in 26 cases, which might be evidence for the decreased cortex reactivity on sensual stimuli.

Any conclusions concerning electroencephalographic examinations made in the studied group of 130 former prisoners should be drawn very carefully, because the group was mainly composed of elderly people. Obrist and Henry (1958) observed pathology in EEG records in 91% of elderly people, Silvermann et al. (1955) in 78% and Barnes (cf. Silvermann et al.) in 65% Jankowski (1959) proved a distinct correlation between the frequency of the occurrence of pathology in EEG records and the old age of his subjects. Moreover, according to Jus (1967), the EEG picture is influenced by not only past traumas and central nervous system disorders but also by internal diseases such as pancreatopathy, thyropathy, suprarenal cortex illnesses, the increase or decrease of base metabolism rate, disturbances in acid‑base and water‑electrolyte balance, or blood sugar levels, which are frequently seen in elderly people.

The results of the electroencephalographic examinations are consistent with the statements made by Luce, Rothschild, and Barnes (1954) that old people, alongside with organic changes, exhibit frequent EEG changes in the form of focal complexes. In our material, as in the cases described by Silvermann and co-authors (1955), the majority of focal changes were found in the temple area on the left side.

Electroencephalographic examinations of the former prisoners of the Nazi camps were performed both in Poland and abroad. Deutschowa (1961) examined 319 former prisoners of concentration camps and observed pathological EEG records in 60% of the cases. Raveau (1961) found diffuse pathological features in 80% of the EEG records. Rogan (1961) observed focal features in 14 of 96 former camp prisoners, paroxysmal complexes in five and scattered slow elements in the form of theta waves in eight cases. Schulte (1953) described electroencephalographic changes that resulted from starvation disease in former concentration camp prisoners. Thygesen and co-authors (1952) also emphasised the importance of starvation disease in the etiology of further organic changes in concentration camp survivors. Electroencephalographic examinations carried out in the Department of Adult Psychiatry at the Medical Academy in Kraków, and performed on 44 persons who had been isolated in their childhood or born in the concentration camps, demonstrated distinct pathological features in 61.4% ofthe EEG records (Gątarski, 1966).

The major observations made during the examination were a great number of pathological features revealed during the electroencephalographic examination of the 130-person group of former prisoners as well as a clear consistency between their EEG pathologies and psychiatric examination results; that is, the diagnosis of organic symptoms, and the fact that pathological features could be more frequently recorded in men than in women.

Translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1969.

References

1. Dąbrowski S., Schrammowa H., Żakowska-Dąbrowska T. Trwałe zmiany psychiczne powstałe w wyniku pobytu w obozach koncentracyjnych i eksperymentów pseudolekarskich [Permanent psychological disturbances after the concentration Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1965; 22: 31-34.2. Gątarski J. Badania elektroencefalograficzne u osób urodzonych lub przebywających w dzieciństwie w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych [Electroencephalographic examinations of persons born, or imprisoned in their childhood in Nazi concentration camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1966; 23: 37-38.

3. Jankowski K. EEG-Picture of Sclerosis and Senile Apathy. Neurol. Neurochir. and Psych. Pol. 6: 827-831.

4. Jus A., K. Elektroencefalografia Kliniczna [Clinical electroencephalography]. Warsaw: PZWL; 1967.

5. Kępiński A. Oświęcimskie refleksje psychiatry [Auschwitz reflections of a psychiatrist]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 21: 7-9.

6. Kępiński A. Uwagi o psychopatologii lęku. Zasadnicze postawy uczuciowe [Remarks on the psychopathology of anxiety: basic emotional attitudes]. Polski Tygodnik Lekarski. 1966; 366-369.

7. Klimkova-Deutschova E. Neurologische Beiträge zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Folgezustände des Krieges. Kongr: Lottich; 1961.

8. Kroeber A. Anthropology Today. University of Chicago Press: Chicago; 1957.

9. Leśniak R. Poobozowe zmiany osobowości byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim-Brzezinka. Translated as “Post-Camp Personality Alterations in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1965; 22: 13-20.

10. Luce R.A., Rothschild D. The Correlation of Electroencephalography and Clinical Observations in Psychiatric Patients over 65. Journal of Gerontology. 1954; 8.

11. Merton R.K., Kitt A.S. Remarks on the Theory of Reference Groups. In Zagadnienia Psychologii Społecznej [Problems of social psychology], selected by A. Malewski. Warszawa: PWN; 1965: 124-150.

12. Obrist W.D., Henry Ch.E. Electroencephalographic Findings on Aged Psychiatric Patients. J. Nerv. Merit. Dis.. 1958; 126: 3.

13. Orwid M. Socjo-psychiatryczne następstwa pobytu w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim-Brzezinka [Socio-psychiatric after‑effects of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 21: 17-23.

14. Półtawska W., Jakubik A., Sarnecki J., Gątarski J. Wyniki badań psychiatrycznych osób urodzonych lub więzionych w dzieciństwie w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych. Translated as “The Results of Psychiatric Examinations of Persons Born, or Imprisoned in their Childhood, in Nazi Concentration Camps.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1966; 23: 21-32.

15. Raveau F. A Neuro‑psychiatric Study of Former Deportees (Document-35). Kongr: Den Hag; 1961.

16. Rogan B. Examination of Norwegian Former Concentration Camp Prisoners: VI Social and Vocational Aspects in Former Concentration Camp Prisoners (Document D-21). Kongr: Den Hag; 1961.

17. Schulte W. Hirnorganische Dauerschäden nach Schwerer Dystrophie. Berlin; 1953.

18. Silvermann A.J., Busse E.W., Barnes R.H. Electroencephalography Findings in 400 Elderly Subjects: EEG Clinic. Neurophys. 1955; 1.

19. Szymusik A. Astenia poobozowa u byłych więźniów obozu koncentracyjnego w Oświęcimiu. Translated as “Progressive Asthenia in Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 21: 23-29.

20. Teutsch A. Reakcje psychiczne w czasie działania psychofizycznego stressu [stresu] u 100 byłych więźniów w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim‑Brzezinka. Translated as “Psychological Reactions to Psychosomatic Stress in 100 Former Prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Doctoral Thesis, abridged in Przegląd Lekarski. 1964; 21: 12-17.

21. Thygesen P., Kielar J. Psychological Deterioration: Starvation Disease in German Concentration Camps, Complications and After-Effects. Ejnar Munksgaard: Copenhagen; 1952.

22. Venzlaff H. Die Psychoreaktiven Störungen nach Entschudigungspflichtigen Erreignissen. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1958.