Authors

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English

Zdzisław Jan Ryn, MD, PhD, born 1938, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and formerly Head of the Department of Social Pathology at the Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków. Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the Kraków Medical Academy (1981–1984). Polish Ambassador to Chile and Bolivia (1991–1996) and Argentina (2007–2008). Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Physical Education (AWF) in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

Introduction

The literature dealing with war medicine and the Nazi Occupation has not yet explored the issue of suicide to any great extent. In fact, the topic of suicide in the Nazi concentration camps has been discussed more widely in memoirs than in medical literature. This paper presents an attempt to outline the problem of such suicide, based on interviews and information gathered from questionnaires sent to a number of former prisoners of the concentration camps. The following questions were considered:

1. How often were suicide attempts made in the population of concentration camp prisoners?

2. What was the proportion of attempted suicide to successful suicide?

3. Who made suicide attempts and for what reasons?

4. What were the methods and mechanisms of committing suicide?

5. When and where was suicide committed?

6. What were the reactions of fellow prisoners and camp staff to suicidal acts?

Special attention has been paid to mass or collective suicide, to suicide committed by women, and to the issue of suicide in the period after the camps were liberated.

It was not without reason that the Nazi concentration camps were referred to as death factories, for their chief objective was the mass extermination of people, mainly those of Jewish origin. Death and dying were such mass and everyday phenomena in concentration camps that prisoners quickly became largely indifferent towards the death of fellow prisoners, and even their own death (Ryn & Kłodziński, 1982). In this context, death through suicide receded into the background, and was often treated as an escape from everyday sufferings. Perhaps this is why, among the multitude of papers dealing with life in concentration camps, so few articles have been devoted to this particular problem.

It is the direct contact between doctors and former prisoners of these camps, and above all former prisoners of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, which has uncovered a high incidence of suicide in concentration camps. Thus, interviews with former prisoners constitute our main source of information concerning this problem (Ryn & Kłodziński, 1976).

As is shown by Auschwitz documents, many prisoners were shot whilst trying to escape. Having analysed these situations, Danuta Czech (1958) concluded that many prisoners deliberately ventured across the SS-guard lines in order to be shot. Thus, it was a way of committing suicide. One may find many similar descriptions in the Calendar of Camp Events, published cyclically in Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim (Medical Review – Auschwitz). These descriptions testify to the fact that it was mostly prisoners of Jewish descent who committed this type of suicide (Czech, 1958).

Information concerning the suicide of prisoners (in most of these cases, through hanging) can also be found in the registry books of the Auschwitz death block. Suicide was entered there under the headings Freitod, Freitod durch Aufhangen, or Freitod durch Erhangen (Brol, Włoch, & Pilecki, 1957). Suicide was also committed by prisoners who were in a state of utter exhaustion, due to starvation. These individuals were referred to as Muselmänner. Indifferent towards everything that went on around them, they lived at the borderline of life and death (Ryn & Kłodziński, 1983).

Suicide through poisoning was particularly common among those prisoners who were members of the camp resistance movement (Kłodziński, 1964). Possession of poison, and the awareness that they might use it at any time, gave courage to the prisoners subjected to exhausting and painful interrogations.

We also know something about suicide committed by members of the SS. They committed suicide either immediately after the liberation of the camps, or later, during interrogation and court trials. From among the Auschwitz medical personnel, Dr. Eduard Wirth, Dr. Hans Delmotte, and Dr. Bruno Weber committed suicide (Kłodziński, 1971). After the war, suicide was also committed by other SS-doctors. For example, Erno Lolling (the chief doctor of the concentration camps) committed suicide in 1945; Percy Treite (medical doctor in the Ravensbrück camp) committed suicide in his prison cell during his trial in Hamburg in 1947; and Wagner (medical doctor in the Buchenwald camp) committed suicide in his prison cell in March 1959 (Ternon & Helman, 1973).

In his book‚ Teufel und Verdammte, Benedikt Kautsky (1961) devotes a short chapter to suicide in concentration camps. The author warns there that statistical figures relating to this phenomenon should not be trusted, since murders were often disguised as suicide. Kautsky observes that suicide occurred very rarely and that in most cases during the first few weeks of camp life, when prisoners were still in the state of shock that was the usual reaction to the conditions of life at the camp. From Kautsky’s own observations of camp life, it appears that the majority of suicides were committed by prisoners wearing a black triangle, which signified people who were morally and/or psychologically unbalanced. There were also many Jewish suicide victims, who were subjected to the most severe oppression in concentration camps. Kautsky observes that suicide occurred much more frequently in the population of concentration camp prisoners than among persons in the outside world.

Every suicide aroused doubts among other prisoners as to whether the suicide victim had been right in ending his or her sufferings. Despite the appearance of being right, notes Kautsky, suicide victims had few followers, although suicide was, by all means, a way of attaining freedom.

Remarks concerning suicide committed by prisoners can also be found in the diaries of Pery Broad, a member of the Auschwitz SS-Political Department (Politische Abteilung). Broad writes:

“The people who lacked the stamina necessary to face this overwhelming situation chose voluntary death after only a few days. Working in teams outside the camp, they crossed the guard lines to get shot, or else flung themselves on the wires... During all the years of the camp’s existence, there were innumerable cases of prisoners who due to an acute longing for freedom and the closest family, starvation, pain, illnesses and cruel beatings, were led to the decision of putting an end to an existence unworthy of a human being. Others were found hanging on their belts from the bed railings. In such cases, the block guard briefly reported the number of suicide victims to the camp manager. The camp’s guards then rushed to the scene of the incident, taking photographs of the victim from all sides and angles; very thorough interrogations were carried out in order to find out whether the prisoner had been murdered by his companions. An unbelievable cynicism enveloped the whole incident.” (Broad, 1965).

Method

This study was based on material collected from two sources. The first was medical reports from former prisoners of Nazi concentration camps with anamnesis, mainly from the Auschwitz concentration camp. The reports were made during the psychiatric examination of 25 former prisoners in the Department of Psychiatry at the Nicolaus Copernicus Medical Academy in Kraków in the years 1972-1975. The other source was written answers to specially prepared questionnaires sent to former prisoners of the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1974-1975. The questionnaires were sent to 40 men and 10 women and included questions covering the already-described research problems. By the end of 1975, 44 responses had been returned to the clinic, including 34 answers from men and 10 answers from women. Six persons did not complete their questionnaires. Only four persons sent back negative answers and maintained that they had never heard of or witnessed any suicidal attempts during their incarceration. It should be mentioned, however, that all those persons were later arrivals in the camp.

Description of the examined group

The age of the respondents ranged from 55 to 75, and the average age was 60. The group was made up of 56 men and 13 women, including 35 persons who were currently married, 36 widowers or widows, and 8 single persons. Regarding education, 38 persons had primary-level schooling, 21 persons had a secondary-level education, and 10 persons had continued to higher education. Fifty-seven persons were receiving invalidity pensions at the time of the interviews, and only 12 persons were professionally active. Twelve former prisoners of the Auschwitz camp had also been interned at other camps, such as Gross‑Rosen, Flossenburg, Gusen, Sachsenhausen, Mauthausen, or Bergen-Belsen. The periods of incarceration ranged between several months and 4.5 years, the average period being 3.5 years.

From a methodological perspective, it should be emphasised that all data mentioned in this paper concerns prisoners of concentration camps who died in the camps. The information relating to these prisoners was obtained from former prisoners who survived the camps. In such a way the information was collected, appropriately selected, and prepared for a critical analysis. This facilitated the specification of a number of details connected with the circumstances, motives, and techniques of suicide in the concentration camps.

General remarks

In view of the opinions presented by many respondents, especially by those who spent several years in the Auschwitz concentration camp, it may be assumed that the number of suicides in the camp came to several thousand cases. They frequently passed unnoticed, because death was so common in the camp. Prisoners died in such great numbers that death was regarded as a tragic norm of camp life. Death surprised nobody, since it happened every day. For almost all prisoners death was inevitable; whether it came sooner or later did not matter. Thus, the sight of corpses was a regular experience, and the prisoners’ reaction was limited to the question of how much effort they would have to make to transport the dead bodies to the crematorium.

Therefore, all the cases of suicide that could still be recollected by camp survivors must have been exceptional. Such suicides either were committed by prisoners who were well known in the camp or were committed in such a way and in such circumstances that the news about them was widely spread among the prisoners. It could be observed that suicidal death in general was certainly more anonymous than deaths caused by camp staff.

Another characteristic feature of suicide in the concentration camp was that successful suicide attempts were much more numerous than unsuccessful attempts. The implications of this are that the desire for death in prisoners committing suicide was deep, and that they did not treat suicide as an act of demonstration, attempted in order to gain the attention and sympathy of others, or aimed at the improvement of the situation. For these individuals, suicide resulted from a previous decision “to become free” earlier, as the prisoners themselves would say.

The consequence of such an approach to suicide could also be seen in the choice of methods of committing suicide in the concentration camp; methods that were always effective and brutal, guaranteeing death, and the impossibility of resuscitation. Such methods were especially drastic among prisoners who committed suicide in a state of psychological breakdown or depression, or among those who were Muselmänner (see above). There was nothing that could stop such prisoners. They prepared their suicide in such a way that nothing could be done to save them.

Who committed suicide?

The survivors’ reports revealed that suicide was committed by both men and women of different ages, different nationalities, and different professions. Their functions and importance in the camp structure were also varied.

The most commonly encountered opinions, however, suggested that suicide was most often committed by prisoners of Jewish origin. They were the ones who were subject to mass extermination and who were most deeply convinced of the senselessness of their situation in the camp. In the women’s part of the concentration camp, Jewish women also accounted for most of the suicides. Among the descriptions of many different cases, there was also reference to suicide committed by prisoners of French, Yugoslav, Dutch, Greek, Czech, Russian, Polish, and German origin.

White-collar workers were least resistant to the camp trauma. Unaccustomed to the hardships of life, they were the first to break down. Some of them had been spoiled by their pre-camp life; they had never experienced hunger, physical effort, or difficulties. Before they entered the camp, they had never had to work physically and usually had few, if any, financial problems.

When was suicide committed?

Although it is difficult to estimate precisely, the majority of suicides were undoubtedly committed in the first two years of the camp’s existence. This fact was confirmed by the majority of former prisoners, and especially by those who were incarcerated in the Auschwitz camp from its beginnings. The years 1940-1942 were the most arduous regarding discipline, terror, and mass extermination of the prisoners. In that period, the camp staff consisted of the worst “functionary” men, especially barrack overseers. It was also a period of terrible epidemics. All those factors made it even more difficult for the prisoners to survive physically and psychologically, and brought frequent suicidal thoughts and decisions. Cases of suicide were much less numerous in the years 1943-1944. The discipline in the camp was not so strict during this period; the underground resistance movement was now in operation; supplies of extra food were illegally brought to the camp; medical aid was organised; and it was easier to change to less difficult work. It was also easier to help and stop prisoners who had decided to commit suicide.

Motives for suicide

The statements made by the former prisoners suggested that motives for suicide committed in the concentration camp could be classified as “direct” and “indirect”. The first group would include all traumatic factors connected with the incarceration period, such as imprisonment, changes in the camp hierarchy, drastically difficult financial situation and living conditions, starvation, diseases, extremely hard work, and the constant danger of repressive measures and death. The second group would consist of any psychological and somatic traumata or any circumstances directly connected with a prisoner that might constitute a cause of attempted suicide. The motives in this group would also include intra-psychological factors, such as mental illness.

The most frequently encountered motives for suicide in the concentration camp were as follows: psychological disturbances (mainly states of depression of varying intensity and etiology), somatic illnesses, fear of torture, fear of being denounced, loss of a relative or friend, disappointment in love, physical assault, and feelings of patriotism and altruism.

Psychological disturbances

In the majority of prisoners, loss of freedom and incarceration in the concentration camp produced at least temporary reactions of depression. The descriptions of suicide very often pointed to the fact that prisoners took their own lives in a state of psychological breakdown or depression. For example, a doctor from Warsaw incarcerated in the women’s camp committed suicide for psychotic reasons. Whilst suffering from typhus, she also showed symptoms of psychological disturbances. She was depressed, experienced great fear, and possibly hallucinated. She had suicidal thoughts and talked about them when she had a high temperature for several days. Her prison mates looked after her all the time to ward off a tragedy. A short unguarded moment, however, was enough for her to run out from the barrack and rush in the direction of the barbed wire. A German doctor called out to the guards not to shoot her because “she was mad”. Unfortunately, despite this, she was shot before she managed to reach the wires.

Somatic illnesses

W. Broniszewska, a prisoner at Auschwitz, described a young Polish woman who was taken ill with cancer of the abdominal cavity. Because of a dangerous haemorrhage from the vagina, a laparotomy was performed on her. The operation was carried out in the men’s ward. After the operation, the patient could not stand the pain, escaped from the sick room, and tried to fling herself onto the wires. Another prisoner, a young actress from Warsaw opera, was taken ill with tuberculosis. Before the illness, she was brave and active, and organised performances for her fellow prisoners. After she learned about the diagnosis, she broke down and cut her veins at night.

The menace of death

In many cases, suicide in the concentration camp was caused by the direct danger of death. In a situation when death appeared to be a question only of time, many prisoners shortened the period of awaiting their sentence and execution by committing suicide. In the Auschwitz concentration camp, inevitable death was the fate for those who were caught whilst escaping. Therefore, it was only natural that many of the unfortunate escapers decided to end their lives by suicide even before they were caught and interrogated.

One of the famous events in the Auschwitz camp was the romantic, and at the same time tragic, love story of Mala and Edek. The young couple were well known in the camp long before their tragic end. Many concentration camp survivors referred to this story because it ended with two successful suicide attempts. Mala and Edek’s story has become the basis for both literary and film works.

Mala (camp no. 19880) was a Polish Jewess. She was young and pretty, and knew several foreign languages. Edek’s full name was Edward Galiński (camp no. 531). He was industrious and clever, and had numerous contacts at various levels of the camp hierarchy. Together, they carefully prepared an intricate plan of escape from the Auschwitz camp. Although the escape itself was a success, they were caught and returned to the camp. They were sentenced to death. Wiesław Kielar, an eyewitness to the execution and author of the famous book Anus Mundi wrote that after the sentence was read out to him, Edek put his head through the loop and jumped down from the scaffold.

“He kept his word! he did not allow the hangman to handle him!” (Kielar, 1972, p. 408).

Like Edek, Mala did not allow the SS-men to carry out the execution. When she was at the scaffold and the sentence was being read to her, she cut her veins with a razor blade she had smuggled in with her.

“The furious SS-men mutilated her body in front of the entire women’s section of the camp. Mala died on the way to the crematorium” (Kielar, 1972, p. 408).

Emotional motives

Prisoners appeared to be especially susceptible to emotional disappointments, most of all to love tragedies. The loss of a relative, a friend, or a lover led to many psychological breakdowns and increased the menace of death in the camp, especially of suicidal death. This applied to the loss of relatives and friends outside the camp, as well as, or even to a greater degree, to similar losses in the camp. For instance, one of the younger prisoners received a letter from his family and learned that his beloved had married another man. He was in despair; he could not recover from the fact that she did not wait for him to come back from the camp, or as he put it at least for his death. He flung himself onto the wires in this state of despair. This suicide resulted from a reaction of depression after the loss of a beloved person.

Patriotic and altruistic motives

The case of Father Maksymilian Kolbe (now canonized by the Roman Catholic Church), who died of starvation of his own free will, is worth remembering here. His death created a sensation; it shocked the whole camp. It was probably the greatest possible sacrifice in the camp situation. Father Kolbe expressed his readiness to undergo death by starvation, a sentence passed on someone else. He was not obliged to do such a thing in any way; he was not in danger of extermination. He voluntarily directed destructive forces against his own life in order to save the life of another human being.

This was a special case of a “substitute death”.

A suicide committed to save another person or for the sake of some great cause is not one that violates any specific moral value. On the contrary, such suicide may be regarded as an ethically creative element and may raise a human being to a higher level of humanity.

Methods of suicide

It was evident from the collected material that the most common, most numerous, and most easily available method of committing suicide in the concentration camp was “flinging oneself onto the wires” (Polish pójście na druty or rzucenie się na druty). As noted below, this could be any form or style of contact with the electrified barbed wire surrounding the camp. In general, death came at once, and often the body of a suicide victim was charred. Sometimes, however, it happened that death did not come immediately, and the victim died in pain. In some cases, it was still possible to tear a victim away from the wires with the help of a wooden stick or clothes. It is impossible to assess how often suicide was committed and how many prisoners died in such a way. It can certainly be stated, however, that suicide was a mass phenomenon and that this was the most common form of suicidal act.

“Flinging oneself onto the wires” was usually done at night or at dawn; these were the best times. In different situations, it looked different. By the accounts of eyewitnesses, some prisoners sprang to their feet and rushed to the wires; others approached slowly, as if with ostentation and ecstasy. It also happened that prisoners unexpectedly tore away from the assembly and flung themselves onto the wires in front of thousands of prisoners and many functionaries. In the women’s camp flinging oneself onto the wires was also the most common way of committing suicide.

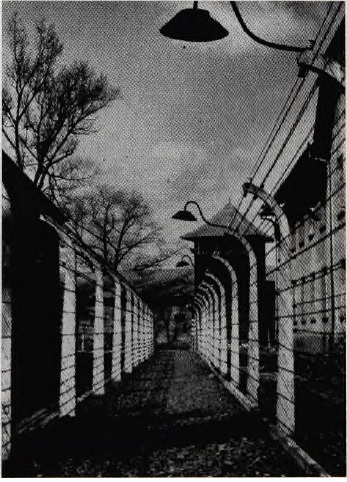

The electric fence and a guard tower at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Photograph by J. Kuś

Suicide by hanging held second place. Prisoners committed suicide in such a way in secluded and isolated places such as cellars, attics, deserted barracks, or structures that were just being built. Sometimes it happened, though, that prisoners hanged themselves in the presence of their prison mates in their barracks, in the bathroom, or in bed, where apparently there was the possibility and time either to prevent the suicide or to resuscitate the victim.

Prisoners sometime sought death by poison. They sometimes used iodine or some other less well-known chemical reagents, but the most effective and common ones were cyanide, arsenic, and strychnine. Such suicide included an extremely rare case of committing suicide by swallowing cement. This case was recorded in the Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke, Holzplatz in 1942. The prisoners had been starved for a long time. They were busy mixing cement. Suddenly one of them exclaimed, “Listen, friends! We’ll have a lot to eat finally! Just watch!” He then began to swallow cement greedily and washed it down with water. For a short time, he was excited, shouted for joy, and encouraged the others to follow his example. In a moment, however, he was seized with a fit of pain and died quickly. All descriptions provided by the concentration camp survivors give evidence that prisoners were able to use the most improbable situations to commit suicide. In September 1942, an underground organisation was discovered. The organisation included tailors, shoemakers, leather tanners, and dog trainers. In order to avoid interrogation, two of the prisoners jumped into a pit of poisonous tanning liquid and drowned.

Mass suicide

Among the reports that came from the camp survivors, there were descriptions of eight cases of mass suicide.

In the Auschwitz camp mass suicide started with the first Russian prisoners. At the beginning, after evening roll call, when they were given very small portions or when they were not given any food at all, many starved and depressed prisoners flung themselves onto the wires.

Suicide committed by women

Suicide committed by women was much more frequent than is usually thought. Although the collected information is not enough to permit statements about the specific etiological factors behind women’s suicide, it may be observed that there were some differences between suicide committed by women and suicide committed by men. Differences can also be observed in the ways in which suicide was committed.

The first suicide recorded in the women’s camp was probably committed by a Jewish prisoner from Slovakia on May 12,1942. She was the eldest of three sisters incarcerated in Barrack 9. She committed suicide out of worry for her sisters. She spent several evenings in the attic of Barrack 9, watching the wires, and tried to estimate the distance she would have to cover as quickly as possible in order not to be shot by a guard. She tried to persuade her sisters to commit collective suicide. Unwatched by her fellow prisoners and sisters, she committed suicide unobstructed.

Suicide was especially frequent in the autumn of 1943. Flinging oneself onto the wires was an everyday occurrence. Prisoners of Jewish origin of different nationalities – French, Greek, German, Czech, Yugoslav, and Polish – committed suicide most commonly. They were the least resistant to camp conditions, easily broke down in the absence of any moral support in the form of letters or parcels, and were not able to communicate in the foreign language.

Camp conditions were most difficult for women with children. They worried not only about themselves, but also about the fate of their children. Similarly, the eldest siblings worried about their younger brothers and sisters. That is why mothers and eldest siblings most often suffered from psychological breakdowns. Children and younger siblings were usually in a good frame of mind. This remark may be supported by the following case of a collective suicide committed in the camp and described by A. Tytoniak: Tytoniak had watched the Lachs family for a long time. The Lachs lived in Block 6 in the Auschwitz camp. The family consisted of three persons: a mother and two daughters. They worked in a straw mat workshop. Mrs. Lachs was the wife of a Slovak doctor. She and her two daughters were brought to Auschwitz in one of the first Slovak transports. She was exceptionally beautiful. She kept her grey-haired head high and had a slim neck; according to Tytoniak her elegant head resembled a work of sculpture with a frozen expression of pain. She always kept her daughters in front of her where she could see them – at work, during free time, at roll call. She used to gaze pondering at their backs, whilst automatically making straw plaits several meters long. Her whole attention was concentrated on her daughters; otherwise, she noticed only such things that might possibly be dangerous for her daughters. She moved very cautiously. She cast her eyes restlessly about, ready to notice danger and warn her daughters, who were always ready to obey her instructions. They did not make any decisions by themselves and did not act on their own.

Once, Mrs. Lachs stole two unpeeled potatoes from the cauldron. Though she was chased by a group of prisoners and beaten by those who were on duty, she managed to escape and bring the precious objects to her daughters. She also used to save her portions of bread for them; often during work, she would divide it into pieces and give it to her daughters. Day by day, she grew increasingly thinner, and her eyes lost lustre and looked faded. Such were the eyes of those awaiting death. She kept four pieces of cardboard in her breast pocket. She used to give them to her daughters to stand on during roll calls. It was the rule that, until the end of November, prisoners walked barefoot.

In August, the women’s camp was moved to Birkenau. The mother and her daughters disappeared for some time. Finally, on 1 October 1942, figures of women dressed in Russian prisoner-of-war uniforms emerged from the nocturnal mist. They were going in the direction of the wires. The mother and daughters could be easily recognized. The elder daughter was in front; the mother led the younger by the hand. They were approaching the wires between the kitchen and one of the barracks. A guard was on duty by the food store all night. When asked what they were doing, Mrs. Lachs said,

“Don’t ask questions. You know where we are going. There is no point in living any longer. To die today or tomorrow... I cannot stand the torment of my daughters... Don’t stop me!”

The younger daughter held her mother’s hand and looked into her eyes with terror and hope that she would still change her mind. The elder daughter stopped for a second only and then went on like a sleepwalker, deciding to accept death, resigned to her fate. It was the eldest daughter who first flung herself onto the wires; the younger was pushed by her mother. In the end, the mother herself stood erect and slowly knelt down.

For its tragic significance, unusual course, and its motives, this little known case of suicide in the women’s camp deserves more detailed analysis and broader familiarity, since it constitutes a dramatic example of the consequence of camp terror.

Prisoners’ reactions to suicide

At the beginning, prisoners reacted spontaneously with shock and grief to the death of their prison mates. After some time, however, when death became a common everyday phenomenon, a specific apathy developed, and they reacted neither to a fellow prisoner’s death nor to the sight of a corpse. They also ceased to be moved by suicide, wondering whether it might not be a better alternative than endless torment. Gradually, however, total apathy became the only reaction.

Discussion and Conclusion

The descriptions given above of various types of suicide in the concentration camp clearly illustrate their specific dissimilarity concerning both the motives and the ways of committing suicide. It is certain that suicidal death was a mass phenomenon under camp conditions and that uncounted masses of prisoners were its victims. Like all other types of death in the structure of the camp, suicide of every kind evoked unofficial acceptance on the part of the functionaries.

In the whole of the literature dealing with suicide, it would be difficult to find any analogies to many factors typical of suicide in the concentration camp. First, successful suicide was definitely much more numerous than attempted ones. Some analogies could be found in the category of suicide committed by mentally ill persons suffering from depressive or endogenous psychoses, where the co-efficiency of successful suicide is very high (Broszkiewicz et al., 1974).

Suicide was usually attempted by prisoners who suffered the cruellest harassment by camp staff: They were most often prisoners of Jewish origin, foreigners, white-collar workers, and prisoners more advanced in age. These individuals found it most difficult to adapt to the camp conditions.

The lowest number of suicide cases was recorded in the first months of the camp’s existence. Later, a rapid increase was noticed in the first two years of the camp. This was the period of greatest terror, mass extermination, the increased activity of gas chambers, infectious diseases, and pseudo-medical experiments; all these factors combined to form a situation in which survival was most difficult. Suicide was particularly frequent in autumn and winter.

The usual motives of suicide attempts were psychological disorders (in the form of depressive-anxious syndromes that could be referred to as psychological breakdowns); somatic diseases; the menace of death; emotional motives; a loss of emotional security; physical assaults; and, finally, patriotic and altruistic motives. The last-mentioned, though rarely encountered, are still remembered as glorious moments of camp history and played an extremely positive part not only during the camp period, but also in the prisoners’ lives after liberation.

The most tragic aspect of suicide was the way in which it was committed. The specificity and sophistication of suicide methods resulted from the refined methods of mass extermination of prisoners in the camp “death factory”. Although responsibility for each suicide committed in the camp belongs to the Nazi torturers, the functionaries were most guilty, since it was they who personally forced prisoners to commit suicide. The collectivity of group life and the possibility of inducing common forms of behaviour were certainly the most significant motives of numerous mass suicides in the camp. They were particularly frequent and tragic in the women’s camp. The suicide of the Lachs family, described here in detail, was one of the most tragic pages of camp history.

Besides annihilation, suicide often had an extremely important function as a dramatic protest against the idea and ideology of the camp. That is why suicide committed in the camp acquired a deeper and broader meaning than those committed elsewhere.

To conclude, let us allow a former prisoner, J. Apostoł-Staniszewska, to speak. She finished her questionnaire with the following statement:

“There, behind the wires, was only fear of life and the courage to die of one’s own will, or fear of death and the great courage to live. Those who managed to overcome their fear of life had a chance to live; those who managed to overcome their fear of death died – the death of suicide.”

Adapted and translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1976.

References

1. Broad P. Wspomnienia Pery Broada, SS-mana oddziału politycznego w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim [Recollections of Pery Broad, an SS Man from the political section of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1965;9: 7-51.2. Broszkiewicz E., Czeczótko B., Universał-Leśniak E., Ryn Z. Samobójstwa dokonane przez osoby chore psychicznie [Suicide committed by mentally ill patients]. Psychiatria Polska, 1974;5: 463-468.

3. Brol F., Włoch G., Pilecki J. Książka bunkra. Przegląd Lekarski. 1957;1: 39-48.

4. Czech D. Kalendarz wydarzeń obozowych. Przegląd Lekarski. 1958;3: 65.

5. Kautsky B. Teufel und Verdammte: Erfahrungen und Erkenntnisse aus sieben Jahren in deutschen Konzentrationslagern. Vienna: Verlag der Wiener Volksbuchhandlung; 1961.

6. Kielar W. Anus Mundi. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie; 1972.

7. Kłodziński S. Rola trucizn jako „ultimum refugium” w obozie w Oświęcimiu: Dr. Jan Zygmunt Robel [The role of poison gas as the last resort in the Auschwitz Camp: Jan Zygmunt Robel, M.D]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1964;21: 122-124.

8. Kłodziński S. Esesmani z oświęcimskiej służby zdrowia [SS-men in the Auschwitz medical service], in Okupacja i Medycyna. Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza; 1971: 339-345.

9. Ryn Z., Kłodziński S. Z problematyki samobójstw w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych [Suicides in Nazi Concentration Camps]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1976;33: 25-46.

10. Ryn Z., Kłodziński S.: Śmierć i umieranie w obozie koncentracyjnym [Death and dying in the concentration camp’]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1982;39: 56-90.

11. Ryn Z., Kłodziński S. Na granicy życia i śmierci: Studium obozowego „muzułmaństwa”. Translated as “Teetering On the Brink Between Life and Death: A Study on the Concentration Camp Muselmann”. Przegląd Lekarski. 1983;40: 27-73.

12. Ternom Y., Helman S. Historia medycyny SS, czyli mit rasizmu biologicznego. Warsaw: PZWL; 1973.