Author

Adam Szymusik, MD, PhD, 1931–2000, Professor of Psychiatry, Head of Chair of Psychiatry, Head of the Department of Adult Psychiatry, Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków. Former President of the Polish Psychiatric Association.

Health problems in former concentration camp prisoners were first explored in France. In 1946, French research workers described a syndrome which they called asthenia progressiva gravis. The term KZ-Syndrome was introduced by Danish doctors and denoted a concentration camp syndrome. Research of this type was carried out in different countries and was usually stimulated by the need for medical certificates supporting applications for disability pensions.

Since 1954, a number of conferences and international congresses on the medical, psychological, and sociological issues of former concentration camp prisoners have been organised. The conferences were held in Copenhagen in 1954, in Moscow in 1957, and in Liege in 1961. The health problems of former prisoners were also discussed at the French Medical Academy in 1956 and the meeting in Paris in 1961 was dedicated to the health issues of Jews who had managed to survive the Nazi persecution.

Complete reports from the Moscow conference specified the following etiological factors in the progressive asthenia:

- starvation, lack of protein, fat, vitamins, Ca and Fe salts (the camp food was mainly based on starch and usually contained 600 kcal);

- constant cold and scarcity of clothes;

- excessive physical effort for 12-13 hours a day;

- anti-sanitary conditions, lack of space (1 person per 1 m2); an atmosphere of fear and terror leading to the neuro-glandular shock described by Cannon and Selye.

The above factors resulted in the following effects:

- the spread of infections;

- increasing malnutrition leading to the decrease of blood sugar levels and muscular atrophy and, consequently, to a negative protein balance, protein metabolism disturbances, increased capillary permeability, accumulation of fluids in the inter-tissue areas accompanied by dehydration, and desiccation of cells. These resulted in the impairment of endocrine-gland activity (mainly of the thyroid glands and reproductive organs), and only the suprarenal glands maintained their activities for long;

- nervous stress caused by physical factors decreased nervous resistance, which in turn led to greater susceptibility to physical stimuli.

Regarding pathogenesis, it is usually assumed that the basic function in the development of asthenia was the after-effects of dystrophy and psychological shock; however, the importance of the specific factors has not yet been specified. Bastiaan believes that brain injury may be the reason; Kreindler, Eitinger, Thygesen, Hermann, Kieler, Gukassian, Hagen, Hoffmeyer, Michel, and Eicke maintain that the basic factor responsible for the development of asthenia is alimentary dystrophy and the resulting brain damage. They quote the Minnesota experiment, in which 36 male patients were malnourished for half a year. They were allowed 1570 kcal a day and, as a result, they developed a psychoneurotic syndrome, referred to by the Americans as “starvation neurosis”.

Women prisoners in barracks at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp

Targowla and Gilbert-Dreyfus suggest an idea of nervous hypertonia, which stimulates the hypothalamus, and they believe that psychological factors, states of tension and anxiety, and difficulties in adjustment to post-camp life are axial. Therefore, the symptoms of asthenia could frequently be observed only after former prisoners went back to their professional work.

Partnow, Rappaport, and Fiedotow emphasised psychogenic factors even in post-traumatic phases. Hoffmeyer stressed the basic function of living conditions after liberation, although he agrees that starvation constitutes the main etiological factor. He also mentions an additional factor: the conviction that suffering was pointless, in view of the new political situations.

In addition to taking etiology and pathogenesis into consideration, many authors include descriptions of symptoms and pathologic syndromes observed during the progress of asthenia in former prisoners.

At the Moscow conference, the following clinical types suggested by Targowla were specified, with a phase of latency characteristic of all types:

- moderate/not very intense,

- serious with symptoms of depression,

- choleric,

- hypochondriac with dominant digestive system disorders,

- emotional paroxysmal hypermnesia syndrome.

Pre-senile involutional neurasthenia constitutes a separate group. It is similar to involutional depression except that it is accompanied by symptoms suggesting organic lesions. It usually takes the following course: total exhaustion and weakness symptoms, a clinical manifestation dominated by defective memory and attention disorders, and emotional apathy. Other symptoms that may develop include anxiety, emotional instability, uneasiness, serious sleep disturbances, and depression. This type of syndrome appears after the age of 40, usually between 50-60, although there are cases when it has appeared at the age of 35.

The following symptoms are regarded as most characteristic for asthenia: tiring easily, which appears in 90 percent of the subjects examined and for three-quarters of the subjects constitutes a permanent problem at work. Tiredness usually begins in the morning and intensifies towards the end of the day. It is accompanied by a feeling of pressure in the chest, periostal aches of the legs, headaches in the form of pressure in the forehead, a feeling of emptiness in the back of the head, and the so-called hypo-dynamia of sight and hearing activities. In two-thirds of the cases, cardiovascular complaints in the form of tachycardia paroxysmalis, extrasystoles, and precardial pains, and a tendency to have high blood pressure can be observed. Among digestive system disorders, gastric and duodenal ulcers, chronic intestinal ulceration, and periodic bacterial and amoebic diarrhoeas occur frequently. Cattan arrived at similar conclusions based on the results of examinations carried out in a group of Jews.

The symptoms of asthenia also include endocrine secretion disorders, which can appear after a latency period of several years, or increased irritability in the pre-menstrual period. Cases of adiposity may also be encountered: plethoric in men and spongy in women.

Gilbert-Dreyfus also mentions secondary hypoadrenalism, which appears because of functional pituitary damage. It is accompanied by hypotonia, emaciation, anorexia, digestion disorders and a lower serum level of corticoids. Hormonal compensation is achieved only after starting professional work again.

Neuropsychological changes constitute the most serious asthenic disorders. They include energy loss, periodic depression, inferiority complexes, tendency to be excessively self-critical, and suicidal thoughts. Changeable moods, irritability, and dysphoria are often present. Other symptoms include a lack of self-control, emotional instability, a less intensive emotional life, the inability to express enthusiasm, the tendency to avoid people, and living in seclusion. Not infrequent is the conviction that those around the subject are unable to understand him.

Holocaust survivors usually have difficulties in acquiring new knowledge and problems with concentration, and complain of an inability to follow lines of thought. The results of tests show defective memory and association of ideas, attention disorders, and tiring easily.

The following symptoms are also very frequent: dysestesia, unspecified pains and paresthesia in the back of the head, forehead, temples and face, radiating to the cervical vertebrae. Cervicalgiae, lumbalgiae, and paresthesia of the legs require their constant movement and cause sleep disturbances. Additionally, dizziness, a feeling that the mind is blank, uncertain movements, and a fear of falling over can also be observed.

Sleep is disturbed, heavy, does not bring good rest, and is often accompanied by fearful dreams. The use of sleeping pills leads to waking up suddenly at night, shaking, nystagmus, and sometimes to focal symptoms or epileptic seizures. Supplementary tests of cerebrospinal fluid and X-rays of the skull, as well as pneumocephalography, do not show permanent changes. The electroencephalogram is sometimes abnormal; flat waves or occasional peaks appear.

Asthenic disorders affect the whole personality and lead to distinct changes. Three fifths of the subjects examined had to change their jobs or limit their work because of adjustment problems. Sixty percent were declassified.

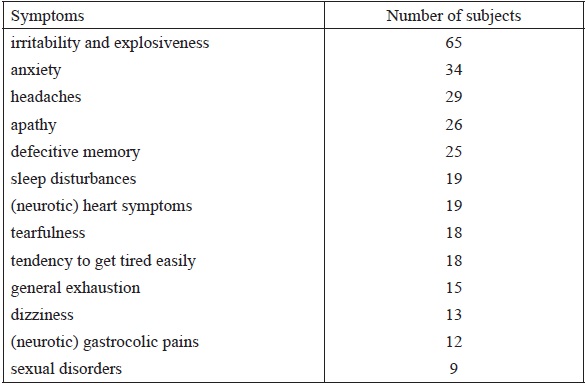

Table I: Symptoms observed in prisoners

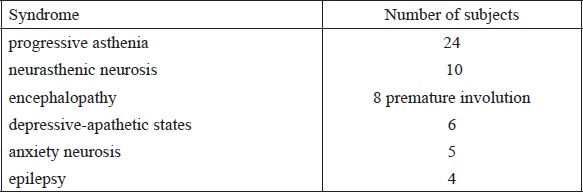

Table II: Syndromes observed in prisoners

One special type is formed by attacks of consciousness disturbances, specified by Targowla as the syndrome of emotional paroxysmal hypermnesia with retrograde amnesia. This comprises psychomotor attacks, during which camp scenes are brought back as a kind of series of events. Such seizures are accompanied by deep anxiety, and usually end with amnesia. Also encountered are sub-clinical forms with the features of oneiric automatisms, and obsessive preoccupations accompanied by the dimming of consciousness. This syndrome resembles hysteroepilepsy.

Strauss and Kolle describe a specific disorder that, as they state, mainly appears in Jews. They call this syndrome a chronic reactive depression. It cannot be compared to depression that usually follows psychological traumas. Even the most depressed person retains his ability to work, but in the case of Jews who survived the Nazi persecution, psychological breakdowns lasting for many years can be observed.

Further syndromes specified by these authors, independently of each other, are development and adjustment disorders found in young people. According to Kolle’s view, these people were left as wrecks after the war, and freedom did not offer them any better position. They were supplied only with the necessary material goods but left without emotional support, which was essential for them. Levinger believes that Israel offers exceptionally good conditions for these young people, since various social organisations usually take care of them. According to him, this is an explanation for the fact that he did not meet many such cases among his group of subjects. Kolle suggests that both groups of disorders should be given the common name of alienation reaction, Entfremdungs-Reaktion.

Examinations conducted by the Department of Adult Psychiatry at the Medical Academy in Kraków show that in 100 subjects, all former camp prisoners, only 36 showed no deviation from the psychological norm. Since we were interested only in psychological disorders, we ignored even difficult cases of somatic illnesses that developed in the camp or soon after liberation, as well as cases of tuberculosis, rheumatic arthritis, and asthma, which are often classified as progressive asthenia.

Out of 100 subjects examined in our department, at the time of the examination, 19 people had higher education, 35 persons had secondary, and 42 primary; 32 subjects were blue-collar workers, 6 were craftsmen, 49 white-collar workers, and 13, most of them housewives, had other professions. There was no interdependence between the frequency of disorders and education or profession. There were 28 female subjects and 72 male ones.

The border between health and illness was not always clearly drawn; to classify the subjects into groups of healthy or sick persons, additional criteria were frequently necessary such as, for instance, working capacities or levels of adjustment.

In order to recognise irregularities, the analysis began with the enumeration of the most frequent symptoms.

A great number of subjects had a strong sense of being wronged, alienation, and often an inferiority complex, regardless of the symptoms mentioned above.

Based on symptom occurrence and development, the following clinical syndromes were specified: There were a number of cross-symptoms: for instance, the progress of asthenia was sometimes accompanied by anxiety states or encephalopathy transforming into premature involution after several years. There were also several cases of psychoses and alcohol abuse; however, these were incorporated into the appropriate syndromes based on the prevailing symptoms appearing in the clinical manifestation.

Psychological disorders appeared in the following periods: in 41 persons a year after the camp experience, in 9 persons from one to five years after the camp experience, and in 14 persons from five to fourteen years after the camp experience.

In several cases, the symptoms of psychological disorders were already present in the pre-camp period or certain extra factors appeared in the post-camp period, which ruled out a statement of the clear causal nexus between the disorders and the camp experiences. However, in 48 cases the causal relationship was absolutely clear.

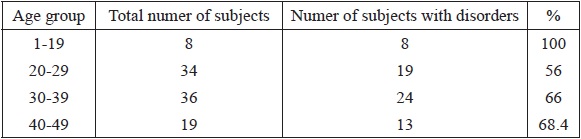

Table III: Age groups and numbers of subjects

Taking the progress of the disease and dominant symptoms into consideration, the following clinical syndromes could be specified:

– Epilepsy characteristic of frequent seizures. Out of four subjects suffering form this illness, the cause and effect relationship with the camp experiences was obvious only in two cases. One of the subjects had epileptic seizures since 1919, and after the camp, the seizures only intensified. In the other case, the seizures came in 1958 though there were clear asthenic symptoms before.

– Encephalopathy. This diagnosis was made very carefully, only in cases supported by clinical observation or when the psychological state combined with neurological or electroencephalographic disorders clearly pointed to this illness. In many unclear cases, that suggested at least cerebrasthenia, asthenia or neurosis were diagnosed instead. The symptoms indicating encephalopathic changes appeared either immediately after the camp period or soon after liberation, after some additional psychological trauma. The following factors were dominant in the clinical manifestation: irritability, explosiveness, headaches, dizziness, defective memory, emotional instability, and poor working capacities. In some cases, intellectual apathy could be observed. States of apathy and depression, sleep disturbances, and complaints of heart and gastric problems were infrequent. Some subjects showed a lowered level of self-criticism, and they became engaged in activities that they could not manage. There were a relatively high number of cases of habitual alcohol abuse accompanied by a distinctly low level of tolerance in this group. In four cases encephalopathy intensified, which might suggest premature involution.

In the group of premature involution, the following factors were axial: general exhaustion, poor working capacities, tendency to tire easily, worse moods, apathy, defective memory, sleep disturbances, and heart problems. Diminished sex drive could also be regarded as characteristic in this group. Irritability and explosiveness were of secondary importance. Torpidity of psychomotor activities, emotional instability, and distinct symptoms of apathy were objectively recorded. In two out of seven cases, involution was preceded by a long period of alcohol abuse. Characteristically, members of this group demonstrated mild neurotic symptoms for many years.

In the group of progressive asthenia, the characteristic feature was the progress of the disorders. After shorter or longer periods of a lack of working capacities, usually from six months to four years, the subjects went back to professional work, but often could not cope with it. They thus changed jobs and finally retired in the majority of cases: they were not able to perform their duties properly. At the time of the examination, premature involution could be observed in many subjects alongside inferiority complexes and the conviction that they were entirely inefficient. Besides irritability, explosiveness, and vegetative ailments, anxiety and depressed thoughts about the camp dominated in the clinical manifestations. A sense of being wronged and alienation, tearfulness, tendency to tire easily, and a sense of general exhaustion were equally frequent. Worse moods, apathy, and sleep disturbances also constituted major symptoms. Cerebrasthenic symptoms in the form of headaches, dizziness, and defective memory were less distinct.

Very often, in as many as 8 cases, psychosomatic illnesses such as ulcers (1 case) and hypertension (7 cases) were present.

Asthenic symptoms consisted of states of varied intensity: from those that required long periods of hospitalisation and sanatorium treatment to ones with sub-clinical symptoms, in which subjects retained their working capacities. The character of the syndrome was always chronic and its intensity increased with the course of time. This syndrome was most difficult to treat efficiently.

Among various kinds of neuroses, neurasthenic neurosis constituted the most numerous group and usually appeared several years after the camp period, after some additional negative psychological stimuli. The following symptoms were axial: irritability, explosiveness, sudden changes of mood, sleep disturbances, defective functional memory, and a high tendency to tire easily. Headaches, anxiety, tearfulness, and sexual disorders could be sporadically encountered. With this type of neuroses, which normally lasted longer than the usual periods of neurotic exacerbations, the results of the therapeutic treatment were relatively favourable; however, cases of the recurrence of such neuroses provoked by some apparently unimportant factors were quite frequent. This group included the majority of cases in which the causative clause between the symptoms and the camp experiences might be doubtful.

In the group of anxiety neuroses, there were cases in which illness began immediately after the camp as well as cases in which the first symptoms of disorders were not observed until 1955. Regardless of the time of their appearance, however, the anxiety and obsessive thoughts present in this group were thematically connected with the camp.

Depressive-apathetic states could be observed in four cases immediately after the camp period and in two other cases, several years after liberation. Irrespective of the time of their appearance, the basic factors comprised worse moods, apathy, lack of interests, and separation from their surroundings. As in the case of anxiety neurosis, the clinical symptoms were present for a long time, almost until the time of the examination.

The age of the subjects at their imprisonment was taken into consideration when the attempt was made to specify the factors conditioning the psychological disorders in the former prisoners.

The youngest subject was 14 at the time of imprisonment, and the oldest 57. All the subjects who were incarcerated before the age of 20 suffered from psychological disorders. Other groups did not show any specific differences. The inconsistency between the data concerning the 50-59 age group, and the relevant data quoted in literature were probably accidental, as the members of that group lived in relatively good conditions in the camp.

Out of 100 subjects, several persons had already had neurotic symptoms before the war; in some cases, epilepsy disorders connected with the skull injuries were present. There were 19 such cases altogether. The remaining 81 subjects were cheerful, energetic, resourceful, good-tempered, usually socially committed; in this group the disorders appeared in 45 persons (55.5 percent). Of the 19 persons who showed neurotic and encephalopathic features, disorders were present in 10 of them, and the symptoms were more intense.

When analysing the reasons for imprisonment, the subjects were divided into two groups. The first group constituted subjects arrested for clearly political reasons. This group included persons that were members of illegal organisations even if their imprisonment was the result of individual acts of sabotage, attempts to hide members of the resistance movement, etc. The second group comprised subjects imprisoned as hostages, arrested during street roundups, because of illegal trade, evading compulsory labour, avoiding the imposed payments, etc. In the group of 61 subjects arrested for political reasons, psychological disorders appeared in 34 persons (55.5 percent), and in 30 persons (77 percent) of the group of 39 subjects arrested for other reasons.

The correlation between psychological disorders and skull injuries received in the camp was also taken into consideration. In the group of 68 subjects who were beaten in the camp, frequently until they lost consciousness, psychological disorders could be observed in 54 persons, that is, in 77.8 percent. In the group of 32 subjects without any serious skull and brain injuries, psychological disorders appeared in 10 persons, in 31.8 percent.

The length of the period spent in the camp was also an important factor. Fifty-two subjects spent less than three years in camps or prisons and 28 of them (54 percent) showed psychological abnormalities. Forty-eight subjects were incarcerated for more than three years and 36 persons of this group suffered from disorders (75 percent).

Prisoners of the Mauthausen concentration camp

All prisoners dreamt of surviving the camp period, all lived through moments of breakdown, and doubted whether they would be able to see their families again. At the same time, they all worried about the condition in which they would find their families if they returned home. The prisoners were usually not allowed any news about the fate of their families; many knew, however, that their relatives had also been arrested or imprisoned in camps. Thus, for all of them, dreams of returning home were accompanied by anxiety: what they would find there, and whether they would still be welcome. All of the prisoners were strongly convinced that their suffering entitled them to a special privilege of social welfare since even the most difficult conditions outside the camp could not be compared to the camp life. Therefore, the problem of living conditions after liberation constituted a very important factor in the lives of the former prisoners. But the attitudes of their families and society were more important than the material situations they found themselves in after the liberation.

If those hopes and expectations were not fulfilled for some reason, and the prisoner was not welcomed with proper sympathy and hospitality, or at least with sincerity and friendliness within his environment, his psychological state usually deteriorated. Animosity and lack of understanding led to psychological stress sometimes greater than those encountered in the camp.

Good living conditions were the privilege of 50 persons. In this group, psychological disorders appeared in 23 subjects (46 percent), whereas in the group of 50 persons whose living conditions could be described as bad, psychological disorders affected 41 subjects (82 percent).

Among other data, it should be emphasised that 32 subjects were pensioners, or were not able to work even though they were not yet at retirement age.

Out of the group of 100 subjects, six persons made suicide attempts, in two cases ending in death. Mortality in the group of former prisoners was consistently high; for instance, four subjects that took part in our examinations are now deceased.

29 subjects underwent out-patient or hospital treatment due to neurotic or psychosomatic disorders. For others, therapeutic treatment in the Department of Adult Psychiatry at the Medical Academy in Kraków began immediately after the described examinations.

The following is a short presentation of some cases:

1. A man of 58. A cashier, he had never suffered from any serious illness. He was arrested in 1940 and beaten many times during his stay in the camp. In 1942, he had a serious skull injury, after being hit with an iron rod. He spent several months in the camp hospital. Both before and after the incident he was working as a locksmith, and was involved in making and opening locks. After the liberation, he went back to his job as a cashier. In 1947, he broke into one of the offices and stole several thousand Polish zloty. As a result, he was sentenced to imprisonment, and afterwards he again broke into several institutions, and picked the most complicated locks. He then usually stole nothing. A psychiatric diagnosis qualified him as mentally ill, and he spent a long time in a psychiatric hospital. In 1961, during his stay in the department, he committed suicide by poisoning himself with gas. He was never able to give any reason why he picked locks. The only explanation offered was that he could not resist the temptation to do so. A somatic examination revealed a scar in the central line of his skull; the scar was 15 cm long, around 4 cm wide, and 3 cm deep into the bone.

2. A man of 45, a manual worker, had never been seriously ill. Arrested in 1940 during a street roundup, he was kept in Auschwitz until 1945 and was frequently beaten there. He survived hunger dystrophy. After the liberation, he turned to alcohol abuse. He was irritable, explosive, with a tendency to tearfulness. He complained of sleep disturbances and headaches. Since 1956, he had suffered from lung tuberculosis. As a habitual drinker, he underwent psychiatric hospital treatment four times. He was a pensioner.

3. A woman of 40, a white-collar worker, never suffered from serious illnesses. She was arrested in 1942 for co-operation with the AK (Pol. Armia Krajowa, Eng. Home Army, the Polish underground forces), and was incarcerated in Auschwitz until 1945. She suffered from hunger dystrophy, typhoid fever, and typhus fever. During one of these, she underwent a several-week period of confusion. At the time of examination, she had not been working for four years. Her problems included anxiety thematically connected with the camp, uneasiness, general exhaustion, defective memory, gastric problems, and migraines. EEG results showed a pathological record of the epileptic type. Since the examination, she has been a patient of the Psychiatric Outpatients Clinic.

To conclude, we may state that in the group of 100 former prisoners of the Auschwitz concentration camp, psychological disorders could be observed in 64 subjects: in 48 cases, the causal nexus between the illness and the camp experiences was obvious, and in 16 subjects, such a relationship was only a possibility.

The existence of a connection between the disorders and the camp experiences was supported by the following factors:

1. Pre-camp personalities of the subjects examined, who usually had not suffered from any neurotic disorders and in the majority of cases had been active, energetic, good‑tempered and cheerful;

2. Organic syndromes that appeared after skull and brain injuries in the camp, such as cases of epilepsy, or encephalopathy;

3. The time after which clinical symptoms could be observed. In the majority of cases, this was either immediately after the liberation or several years later, frequently after an attempt to undertake professional work again;

4. Lack of other reasons for clinical syndromes such as premature involution or depressive-apathetic states;

5. Thematic relationships between anxiety or obsessions and camp experiences;

6. A high percentage of disorders that were not found in other social groups;

7. Intensity and long duration of the symptoms as well as poor therapeutic results;

8. Similarities in clinical manifestations.

It would be difficult to give an exact number of the former prisoners who are still alive at present and suffer from psychological disorders, since an examination of the representative groups has not yet been carried out. Our investigation suggests, however, that such disorders may be expected in half of all Holocaust survivors. This number is estimated rather cautiously and appears much lower than it would be suggested by the research done abroad.

There were different clinical syndromes in the group of subjects examined, but their common features were duration and poor therapeutic results. The following symptoms were most commonly seen: increased irritability, tendency to tire easily, anxiety, vegetative distortions, worse moods, defective memory, sleep disturbances, and emotional instability. A sense of being wronged, alienation, or inferiority complexes were also relatively frequent.

The disorders quoted above were connected with such factors as skull injury, hunger dystrophy, and fever illnesses; on the other hand, however, we could also observe the influence of such factors as political commitment, camp adaptation, and especially post-camp conditions, which all appeared to play an essential role in the development of psychological disorders. Gender and age were of less importance though subjects who were imprisoned before the age of 20 suffered from the most intense disturbances. No correlation was found between the disorders and profession or education level.

In the debate on the etiology of asthenic disorders (organic or psychogenic factors), this work supports the view that organic factors are essential but only as predisposing ones, whereas the occurrence of psychological disorders is usually connected with psychogenic factors. In comparison with other works on related subjects, the research method used in the investigation described here allowed mistakes usually connected with pension and reparation cases to be avoided. The sample of the whole population of the former prisoners was examined and the examination was not limited only to the cases of specific clinical complaints. It appears that the psychiatric examination described above was more detailed and exact, at least in the comparison with the methods quoted in other works. In comparison with the results of research done abroad, these are largely the same, though the findings of our investigation are closest to those of Dutch examinations.

The differences between this and other publications can be explained by the fact that the term “asthenia” was used to describe a clinical syndrome observed in former prisoners of concentration camps, and it was not assumed that symptoms in all cases were identical. French researchers presented the same attitude initially and emphasised the fact that the term “asthenia” was typically used in pension cases. Over the course of time, however, the majority of authors started to use this term to refer to all symptoms and clinical syndromes that could be observed in Holocaust survivors. We find it difficult to accept the view of the exclusive importance of organic factors, without considering also the influence of psychogenic factors. The results of the present research appear to contradict the validity of such an attitude.

The final conclusion of the research is that even those few who managed to live through the camp experience suffer from different somatic and psychological disorders, and that the camp period left a permanent mark on their physical and mental health. In some cases, the symptoms clearly suggest a pathological state, but frequently they were only distinct enough to make the readjustment to life difficult.

Translated from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1964.

References

1. Andere Spatfolgen (auf Grund der Beobachtungen bei den ehemaligen Deportierten und Internierten der nazistischen Gefängnisse und Vernichtungslager). Medizinische Konferenzen der Internationalen Föderation der Widerstandskämpfer. Band 2. Vienna: F.I.R.2. Ärztekonferenzen der Internationalen Föderation der Widerstandskampfer. Die chronische progressive Asthenie. Materialen der Internationalen Konferenzen von Kopenhagen und Moskau, zusammengestellt vom (Ärztlichen Sekretariat der Internationalen Föderation der Widerstandskämpfer). Band 1. F.I.R.

3. Kolie K. Die Opfer der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung in psychiatrischer Sicht. Der Nervenarzt. 1958;29: 148-158.

4. Helweg-Larsen P., Hoffmeyer H., Kieler I., Hess E., Thaysen I., Thygesen P., Hertel-Wulf M. Starvation Disease in German Concentration Camps: Complications and After-effects with Special Reference to Tuberculosis, Psychological Disorders and Social Consequences. Acta Psychiatrica et Neurologica Scandinavica. 1952;27.

5. Michel M. Gesundheitsschäden durch Verfolgung und Gefangenschaft und ihre Spätfolgen. Frankfurt am Main: Rederberg-Verlag; 1955.

6. Strauss H. Besonderheiten der nichtpsychotischen Störungen bei Opfern der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung und ihre Bedeutung bei der Begutachtung. Der Nervenarzt. 1957;28: 344-350.