Author

Janez Milčinski, MD, JD, 1913–1993, Slovenian lawyer, doctor, forensic medicine and medical ethics expert. Head of the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Zagreb (1945–83) and of the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ljubljana (1957–1983). Rector of the University of Ljubljana (1973–1976) and President of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts (1976–1992).

This article was first published as “Kriza neke zdravniške etike” in the Yugoslavian periodical Medicinski Razgledi (1965; 2, 1: 147‑157). It was translated from the original Slovenian into Polish by Zenon Jagoda, entitled “Kryzys etyki lekarskiej,” and published in the 1967 issue of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

In the early winter of 1962 the papers were full of articles on the devastating power of a prospective war and speculations that in the event of an on‑target nuclear attack there would be six million fatalities in New York alone.

About the same time a friend gave me a grasshopper in a box with holes punctures in it to allow air inside and a piece of moist cotton wool in a separate compartment. I also got two little notes along with the grasshopper, with instructions on how to feed and look after him and his hygiene. One of the notes said, “Every grasshopper has his own special characteristics and habits. Find out what his favourite food is. See to it that his surroundings are moist enough for him and kept at a constant temperature. Let him make his own choice of the conditions and food he likes best.”

It is amazing that the journalists needed fewer words, and perhaps less time and thought as well, to write about six million dead in New York than this animal lover, who put in so much care and effort into compiling a detailed set of instructions on how to look after a grasshopper before he entrusted his pet to someone else.

I often wonder about that whenever I read Mitscherlich and Mielke’s book Medizin ohne Menschlichkeit (and I’ve read it umpteen times).1 Perhaps it would be better if people who engage in calculating the force of an atomic explosion over New York, Moscow, London, or Berlin took the trouble to consider the habits of grasshoppers and spent some time on studying their characteristics.

That’s what came to my mind when I read those atomic speculations on New York, after the grim impression reading the concluding remarks in Mitscherlich and Mielke’s book made on me. When I saw the vestiges of the last War in Poland the thought of grasshoppers and their singular habits, as well as the problems of humanity and medical ethics, kept coming to my mind.

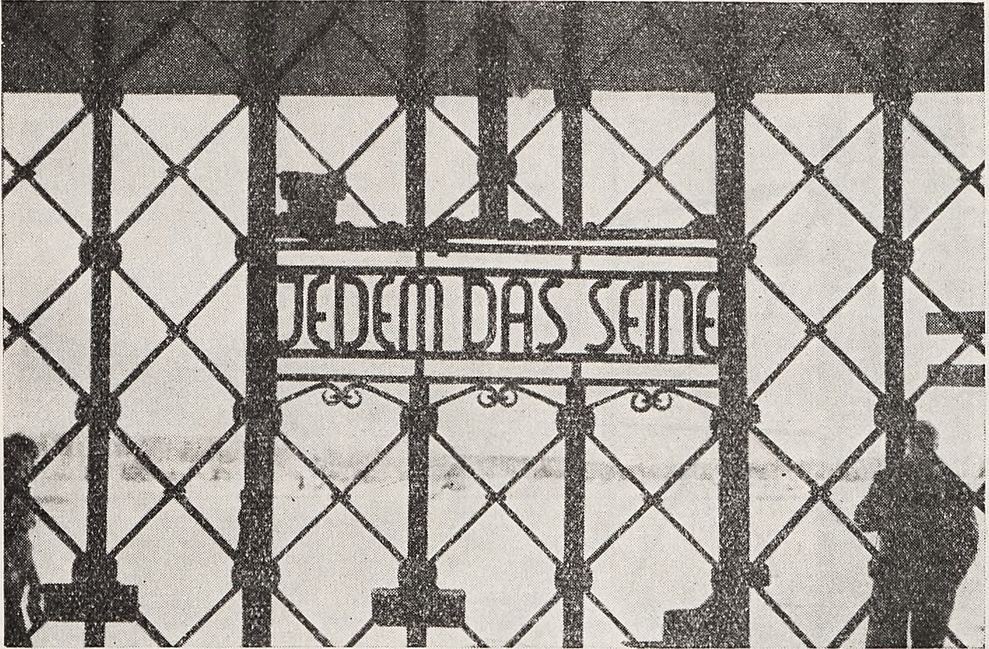

Fig. 1. Auschwitz. The main gate, preserved in the state it was in on 27 January 1945. With the notorious inscription Arbeit macht frei (“Work makes you free”) over it.

“Auschwitz. The Poles use the name ‘Oświęcim.’2 We deliberately call it ‘Auschwitz.’ Oświęcim is a small town with a post office, a railway station, and a marketplace with a row of single‑storey houses around it. Who’d visit this place if it were not for the concentration camp? “Auschwitz” is a concept, a symbol. That’s why we say ‘Auschwitz.’

“The main concentration camp is now in the same condition it was years ago, when it was liberated on 27 January 1945. On the external side of the fence there is a grave with the bodies of about a hundred of the dead found in the blocks [on the day of liberation]. At first they weren’t even noticed among the six thousand survivors whom the camp’s authorities did not manage to evacuate. Before, the numbers in the camp had been as much as 58 thousand. The common grave in front of the fence is the only grave in the vast charnel‑house of Auschwitz‑Birkenau. How little that is for a place where millions lost their lives.

“Everything’s just as it used to be. A double barbed‑wire fence. The external one is up on posts with insulators and notices saying Vorsicht. Hochspannung, Lebensgefahr. (‘Caution. High Voltage. Danger of Death’). On the barrier in front of the wide‑open gate there’s a notice saying Halt (‘Stop’). Over the gate is the notorious inscription Arbeit macht frei (‘Work makes you free’). Beyond are the single‑storey, barrack‑like blocks with unplastered walls, stretching in monotonous rows on either side of the road.

“A few of the blocks have been arranged to house a museum. Behind their glass panels there are clothes and personal belongings taken from prisoners who had to strip before they were sent naked into the gas chambers. These objects, as we can see them today, were found in the storehouses. Whole trainloads of them—mountains of tattered shoes, little cases, clothes, kitchen utensils, piles of boxes of shoe polish, shaving brushes, toothbrushes. A hoard of artificial limbs, arms and legs wilfully smashed to pieces or ripped up (to see if there was any gold or money hidden in them). A separate heap of glasses. Piles of children’s clothes. A train carriage full of women’s hair‑plaited, curly, in bunches, black, blond, or grey. Next to that there are rolls of fabric woven of human hair. It was discovered in the factory where it had been manufactured. Then there are cabinets full of photocopies of the camp’s records—pedantic accounts of how gold teeth were extracted from the jaws of corpses before they were dispatched to the crematorium, certificates, official notices. Lists of prisoners from all over the world. ‘Kraigher Alois, Arzt [medical doctor]’ is one of those on the lists. Elsewhere there are little keepsakes found in the pockets of those who died in the crematoria—amateur photos of people laughing, pocket calendars. Toys—a shabby rag doll, or another, headless doll made of celluloid.

“Block 11. The place of killing and torture (if you can speak of any other type of places in Auschwitz‑Birkenau!). On the outside it looks like any other building in the camp, but you can see it was better guarded, with an iron gate of its own, and small slits instead of windows. Inside there were foolproof safeguards on everything. There was a ‘courtroom’ where a singular sort of ‘court’ handed down death sentences on a hundred ‘accused’ all in one sitting. A bit further on there was an undressing room with an exit leading out into the yard where prisoners were killed. A prisoner had to face his executioners naked, so that his death should not create any costs and for his clothing to cover the cost of the bullets spent on him. In one of the rooms there are ragged items of clothing scattered all over the floor. They have been left in exactly the same way they were found when the camp was liberated. All that was removed from that room were the corpses, just the corpses. In the lower storey there are tiny cells, empty concrete rat‑holes. At the back of this part of the building there are bunkers with standing room only. One of these bunkers was open at the top; we looked down into it and saw a cage like a chimney stack, two metres tall and about seventy centimetres in breadth. At the bottom there was a slotted trap door, like in a pigsty. These were the conditions in which four people at a time were put to die of hunger and thirst. The ones who for some reason or other weren’t good enough for a bullet.

“‘This cellar is where they did the first cyanide tests,’3 our guide tells us dispassionately, as if he weren’t one of those who had to stand to appeal out of doors for hours in the freezing cold, in just his striped prison gear and wooden clogs. ‘Later they had to stop these experiments, because they couldn’t ventilate the cellars quickly enough to dispose of the corpses without much of a fuss.’

“‘This is where the outpatients’ clinic was,’ he continued when we were outside again. ‘Phenol injections. Originally administered intravenously, and later straight into the heart, as it was more effective. Death came faster. There was a special stool on which the “patient” could be made to sit in the most convenient position. Sometimes they would call in children who were playing outside between the blocks. Ten or twenty of them one after another would get a phenol jab in the heart.’”

Yes, outpatients, intravenous injections, injections straight into the heart—well, of course it couldn’t be done without a doctor attending. Neither could many other things, like for instance experiments on human subjects. A doctor designed the experiments which were to show what would happen to a human being who suddenly found himself with no safeguards at an altitude of 15 thousand metres above ground level; or the experiments in which people were kept for a long time in freezing water; or the experiments to see if a desperately thirsty person could take seawater. Medical practitioners devised ways of artificially inducing phlegmons (suppurating inflammation) in subjects to test new drugs. They conducted these experiments systematically and with scientific precision. That wasn’t all. They carried out new operations on healthy subjects; they infected them with contagious diseases; they X‑rayed them to make them infertile. Programmes to annihilate masses of people, the healthy and the sick, to wipe out entire nations the Nazi Germans considered an obstacle to their drive to rule the world—all this was done on the basis of the knowledge and professional skills of medical practitioners.

The Nuremberg Trial

The Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial, which took place from 2 November 1946 to 20 August 1947, disclosed to the whole world the crimes committed by murderers in white coats, enthusiastic implementers of the concepts of Nazism, seized by a mad, pseudo‑scientific ambition and blindly and obediently following their leaders and masters.The records of this trial give an unadulterated account of the crimes committed against specific individuals, against humanity, and against medicine; crimes committed with the use of the instruments and scientific methods of medicine. The trial showed beyond all reasonable doubt that these crimes were not merely barbarous deeds perpetrated by individual physicians. Each of these criminals operated on the grounds of authorisations and instructions issued by their military and police superiors, and none of them failed to insist that he was only acting as a good and trustworthy administrator and a dutiful soldier should. In a word, he was only doing what he had been ordered to do and what was necessary in wartime conditions.

Nonetheless, the defendants were not some sort of small fry of the medical profession; they had not just graduated from medical school and had no professional experience or practice, as you might have thought going by the unconditional way they obeyed orders, which divested them of all the medical and humane virtues. No, not at all—the defendants included seven professors, heads of renowned institutes and clinics, and even the chairman of the German Red Cross.

They were the team of managers leading the other practitioners of a perverse medicine and a perverse science. Its protagonists and executors, and their subordinates at the diverse lower ranks stood trial in various countries. But it would be hard to believe that all of them appeared in court. Even some of the best known vanished in the vortex of defeat and economic miracle. Presumably their biographies are as innocent as the CVs of those criminal physicians who stood trial and were sentenced at Nuremberg.

For instance Herta Oberhäuser had to withdraw from her specialist postgraduate course owing to her father’s illness. When an advertisement appeared in a medical journal on a competition for a doctor’s appointment in Buchenwald concentration camp, she applied for the post. Later she earned the hatred of the “SS clique” working there (as she called them), and started caring for the sick, treating them and bringing relief in their suffering. Almost as innocent as the biography of Karl Brandt. On graduation he wanted to follow in the footsteps of Albert Schweitzer in Africa, but he couldn’t take the crucial step because he was compelled to serve a year in the French army. So he joined the Nazi Party, as he saw no other way out of the situation, and by sheer chance landed up among Hitler’s closest associates. He doesn’t really know how it happened that he joined the SA and SS, how he made it up to the rank of general in the SS and held other senior offices.

Barbaric pseudo‑medical experiments

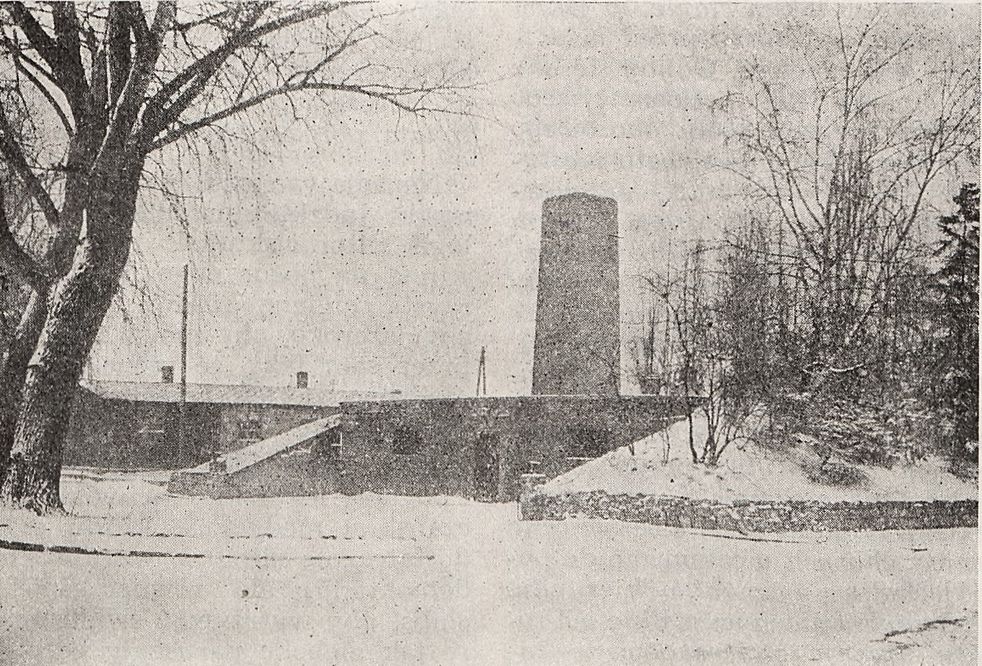

Fig. 2. Buchenwald. Main entrance gate into the camp with Buchenwald’s motto, Jedem das seine (“To everyone his due”).

But then there are the remaining criminals, still at large today but slyly keeping a low profile, criminals with whom nations and humanity as such has a score to settle. As individuals they would not be such a problem for us. Yet what is important now is for us to be on our guard against them in their capacity as carriers of Nazi concepts on medicine. It is absolutely understandable that we should be apprehensive of the crazy ideas with which they infected the “official” medical and paramedical community. They did this either in outcome of direct pressure, or due to blind obedience, or because of the police instinct latent in individuals who feel insecure or have a confused sense of ethics.

Some of them were afraid of showing their reservations about the primitive, barbarous pseudo‑medical experiments such as keeping human subjects in freezing water. Their consciences suddenly fell silent when Himmler issued a warning threatening “people who have still not sanctioned these experiments,” (he meant keeping prisoners suffering from frostbite in hot temperatures), “but are calmly looking on while brave German soldiers are dying due to frostbite. I regard such people as traitors to the fatherland,” Himmler wrote, “and I shall blacklist their names.”

That’s how conscientious objectors were straightaway rendered immune to the screams of those who were being killed in freezing water. The fire of the crematoria did the rest—it freed them from those horrific ghouls, the human skeletons.

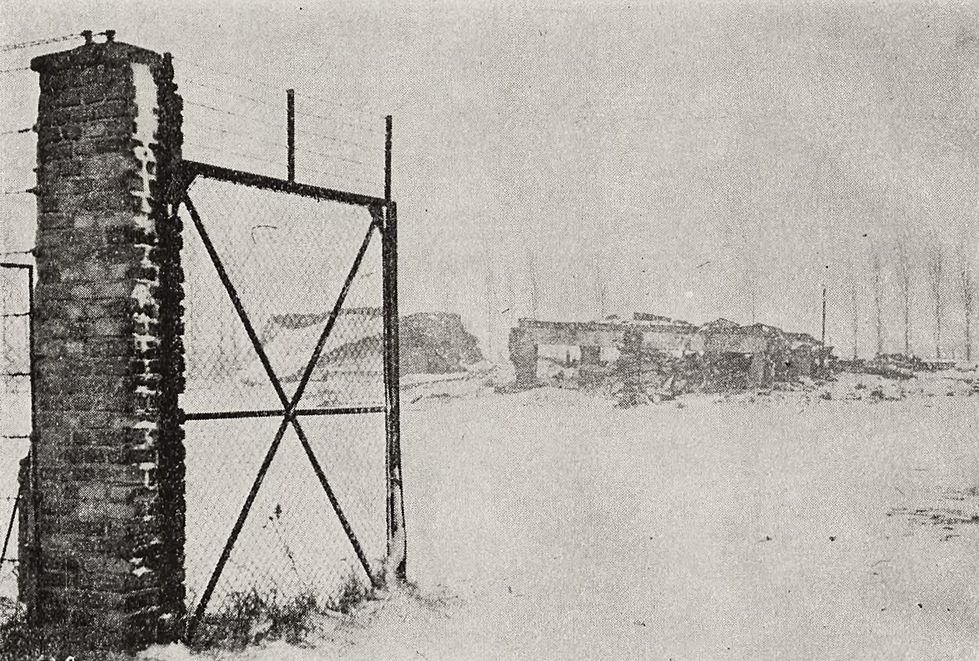

Fig. 3 The Auschwitz crematorium called “the old crematorium” to distinguish it from the four new, updated ones constructed in Birkenau, the adjoining concentration camp, which were mechanised and worked at a faster rate.

“There is an extant Auschwitz crematorium. The building is semi‑sunken and hardly noticeable; all that catches the eye is its quadrangular, not very tall chimney. Inside, its original equipment is still in the basement: the ovens, the iron trucks which were used to shove bodies into the ovens, two at a time to make incineration as fast as possible.

“The crematorium was the bottleneck in a procedure to annihilate human beings designed to leave no evidence. That’s why there was always a backlog of corpses piling up. Eventually they would be pulled out of the gas chambers, doused with petrol or smeared with other flammable materials and burned in the open air. Even the four new crematoria of Birkenau could not resolve the problem, even though they were mechanised and had the full state‑of‑the‑art technology. A railway siding facilitated the transportation of live prisoners and corpses. Nearby there were gas chambers which could kill 3 thousand in one operation using Cyclone B. Victims walked up virtually to the very doors of the crematorium. But even these crematoria were not enough. In August 1944 as many as 24 thousand bodies a day were being burned using various methods of incineration.

“Today all that is on the site of the four huge Birkenau crematoria are the ruins of their concrete walls, preserved in the condition the Germans left them, after blowing the crematoria up before they fled. If the crematoria had been left intact nothing could have been more monstrous in the entire macabre collection of Birkenau’s facilities. This is where in 1943 150 thousand, most of them women, went through indescribable torture, while the Auschwitz camp just 3 km away accommodated 30 thousand prisoners. The crematoria were fed mostly with trainloads of prisoners arriving every day from all parts of enslaved Europe.

“Where was the end of the road for the transport of prisoners sent out from Styria in June 1941? It comprised over 400 patients from the mental hospital in Novo Celje, and at least the same number of old and disabled people from care centres and welfare homes. When they reached Spielfeld the Slovene hospital was evacuated and its patients packed on the train, which set off for an unknown destination. After just a fortnight all the patients’ families received polite letters of condolence notifying them of the death of their relatives. The family of a girl from Ptuj who escaped from the train and went into hiding at home got one of these letters, too. Patients wept as they bade farewell to their hospital, some of them knew what was in store for them. They anticipated they were going ‘to the ovens…’

“To me Birkenau seems even more horrifying than Auschwitz. It is a better fit with the picture of Nazi German concentration camps I had built up on the basis of reading about them. It’s even worse than that picture.

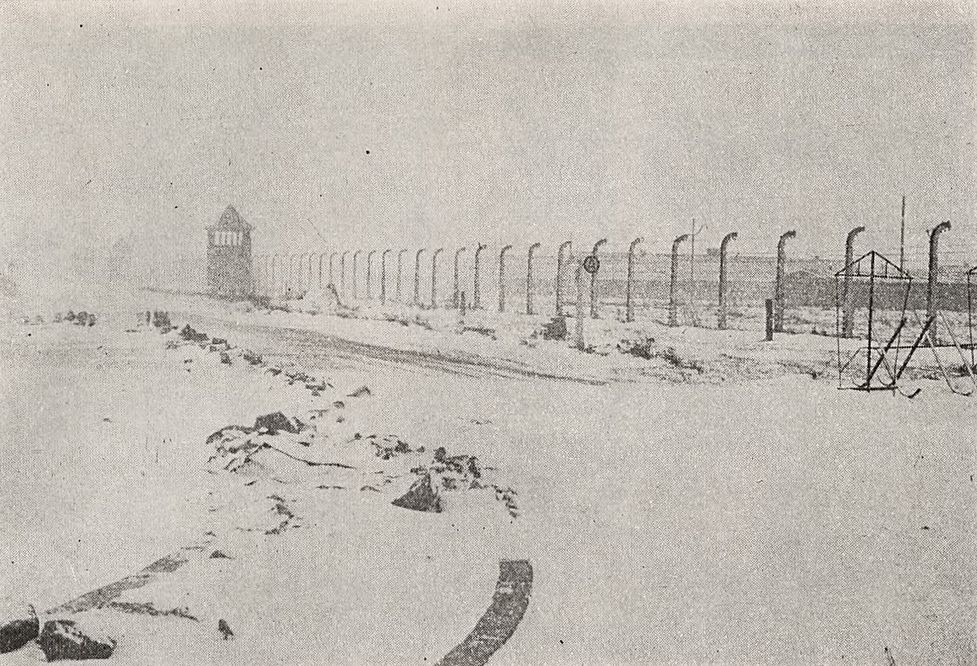

Fig. 4 Birkenau. Crematorium ruins. Before their escape the camp’s management ordered the crematoria blown up. The ruins of their concrete walls and broken pillars are a memorial and a warning.

“The camp extends over a flat plain. It is surrounded by a high barbed‑wire perimeter fence and watchtowers. There are low, dark barracks in straight rows that seem to go on endlessly, one behind another. All grey and empty. There’s not a soul to be seen on the main street that starts from the open gate, not a soul in sight. It’s so quiet you think you can hear the snowflakes falling on the frozen ground. The black eye‑sockets of windows staring out of the disintegrating barracks. It’s a picture of a world that’s dead, hit by an atom bomb…”

The repudiation of the humanist values and of the value of the human individual gradually crept from the Nazi ideology into medicine through the innocuous‑looking eugenics and the absolutely transparent racial hygiene, and established itself firmly enough not to be erased by the mere fact that only a few of its proponents have been sentenced to death or imprisonment.

Fig. 5. Birkenau. A concentration camp for 100 thousand inmates. The high‑voltage perimeter fence and watchtowers. Beyond the fence you can see the outlines of its low barracks.

Its perverted concepts engendered turmoil in the ideas and opinions espoused by physicians; they shook the foundations of bourgeois medicine, whose ethics maybe were strong enough in the conditions prevalent in bourgeois democracy, yet feeble enough to founder when exposed to the global tremors that assailed and posed such a fundamental challenge to values which seemed inviolable. In those turbulent times medicine was on the one hand enriched by numerous discoveries of paramount importance which turned into a powerful tool for the prevention of disease; yet on the other hand it went through a bad time of abuse and medical error, while medical ethics experienced a deep crisis. True enough, even before the War as well as in its aftermath we used to hear of facts and opinions, sometimes voiced by distinguished men of learning, which we would hardly say complied with our moral principles. Opinions on the right of doctors to make use of human health, life, and personality for their own purposes; on the need to sterilise those who were antisocial and useless; on so‑called “truth serum” and narcoanalysis. Also there have been numerous amendments in the legislation of some countries on issues such as euthanasia on a patient’s request, limits to physician’s confidentiality etc.

What is even more terrifying than the fact that years before the War and beyond the Nazi sphere of influence experiments were being conducted on human subjects, experiments which were controversial if not weird from the point of view of ethics—is that the medical community was watching it all with indifference. Putting it mildly, many did not notice there might be something wrong in it.

I am tempted to draw a comparison: aren’t these medical events reminiscent of what was going on in politics—Hitler’s occupation of the Rhineland, the Anschluss, Munich? Was it a symptom of premature ageing, too high a dose of unwarranted optimism, turning a blind eye to the threat of the eradication of our legacy of ethical values?

How far do moral rights go

Great discoveries in medicine and its related disciplines require experimentation by their very nature, and tests on human subjects as well, at a specific stage. The criteria and principles of ethics are being put to the test on a daily basis. Everywhere there are pitfalls, sometimes very well hidden, to trap the ethical health worker. Some of the decisions are very hard.The new rules applicable to pay in the health service and the new criteria for the assessment of a doctor’s work could result in conflicts if we took a primitive approach to the matter. They could easily pose a danger to ethics and put patients at risk. So I believe the time has come for us to think seriously about the problems that Mitscherlich and Mielke’s book has been trying to make us consider.

Now more than ever before we are in need of doctors with the right sense of ethics, aware of their responsibility with regard to their patients and to society at large. Health workers should know the problems which came up at the Nuremberg Trial and think hard about them. For of course virtually all of us come up against variations of those cases in our work during times of peace. If we look closely enough we shall notice certain elements of attempts to conduct a particular type of euthanasia; we will come up against the problem of the patient’s consent, the clash between obeying orders and obeying one’s conscience, between the legal provisions and moral duty. Apart from all this, the new times are continually bringing new issues. For instance, how far does a doctor’s moral right go as regards the mutilation of the human body in patients at the advanced stage of cancer—as is being practised in some countries nowadays? And what about the right to carry out brain surgery to resocialize a mental patient, and in particular to ease his symptoms and make him more comfortable by eliminating part of his emotional life?4 Where is the limit to the use of narcoanalysis? How far may a plastic surgeon go and to what extent dare he acquiesce to patients’ demands?

From Hippocrates to our times

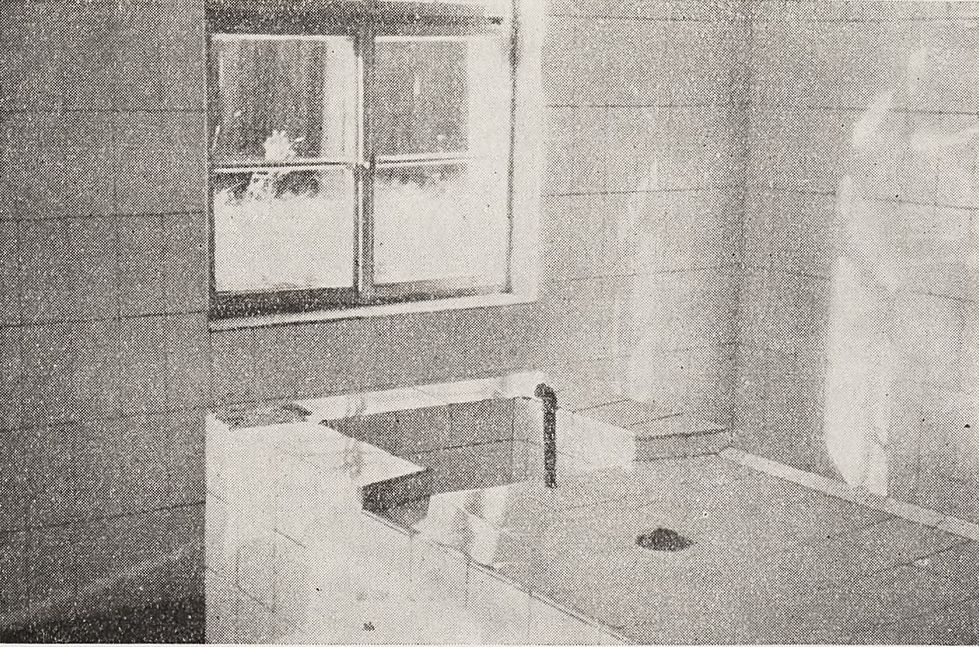

Fig. 6. The medical examination room at Buchenwald. This is where the results of experiments on humans were analysed, and human skin was used to make lampshades or bind books. Today it is part of the museum. There was also an “outpatients’ room” in the building, where patients were killed by being shot in the back of the head.

Do we make responsible decisions solely on the grounds of the principles of deontology shared by all physicians since Hippocrates down to our times? Are we guided by the rule of unconditionally protecting life, unconditionally observing confidentiality, and the requirement to respect the patient’s individuality? Do we always respect their right to decide?

It would all be extremely simple if doctors had no trouble with finding a universal answer to the problems that life brings. Unfortunately, that’s not what it’s like, and there’s nothing we can do about it, it’s just not like that! The principles of medical ethics are full of love of mankind and beauty, and quite understandably they are the foundation from which we can start. They offer a means for the training of physicians and health workers. They serve as a signpost whenever we have to make a decision. But they are only a signpost, not a dogma. Ethical guidelines have a significance and a value if they are put into practice with a full sense of moral responsibility. But that is a matter of interpersonal relations, social order, education and upbringing—a matter of special importance in view of the forthcoming generation of health workers now being educated and trained. It is a matter of concern for academic tutors working in the medical schools and colleges.

Moral education, giving a good example, exercising the right kind of supervision, and the resolute cultivation and promotion of a sense of humanitarianism may serve as the best way to train prospective physicians and help them adopt and build up a moral attitude. We are all responsible for seeing to it that things will take the course we want them to take.

Crematorium soot on the doctor’s lab coat, the stench of phenol coming from his syringe, talk of lives not worth the living—all of that has cost us such a lot, teaching us a lesson at such an exorbitant price that science and education can easily be corrupted.

Inhuman medicine, a regime of bestiality, the planned abuse of human dignity, the systematic devastation of human individuality, the rule of the whip, clog‑fights for a sip of parsnip swill, the monstrous everyday life in the camp and its defiance, defiance down to the last breath, the hopeless struggle of the human skeletons in striped prison gear to save their humanity…

“In one of the glass cabinets of the Auschwitz museum there is a photo of a child with black hair. That little Italian was one of the boys who used to play outside the blocks and who were enticed with cheap bait, an apple or a sweetie, to run up to outpatients for a phenol jab. Prisoners kept this lad hidden away for weeks on end despite the endless searches that went on, despite the threats that they would die if caught. They saved some of their paltry food to feed him; they kept him hidden near the crematoria right up to the day of liberation. Today he’s an engineer—a living proof of human solidarity.

“The tour concludes with a film showing the liberation of Auschwitz. Once more we see animated versions of the images we saw on the photographs in the museum, still more monstrous and more pitiful. Muselmänner standing in their striped camp gear by the open gate and staring vacantly into the camera. They don’t seem to have any hope of taking a single step into freedom. Scenes of the dead being collected up from the blocks, and of doctors examining live skeletons. A procession of a hundred and fifty children found in the camp, walking anxiously and wobbling about in ragged, ridiculously oversize prison gear, holding hands. Their faces gaunt from starvation, dead serious, their eyes huge and asking why. They pass by the camera slowly, these unsmiling children, with no toys, no parents, no homes, no childhood…”

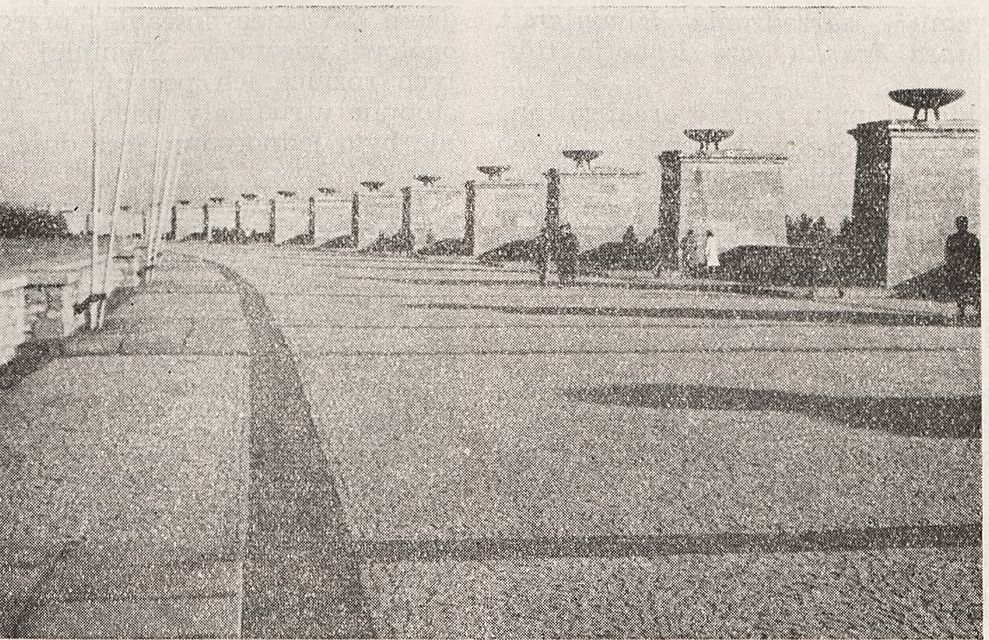

Fig. 7. The Street of Nations running along the Great Memorial in Buchenwald. Each of the columns is named after one of the countries of Europe.

“Some have tears running down their cheeks, their eyesight has gone cloudy. You’re crying—why? For those millions killed? Too many of them, distant and unknown. Or for joy over the survivors? Who’d spend a day or two staying on the ruins of houses and on their inhabitants’ graves? No, it’s not for that. You’re not crying out of hatred, not out of grief, you’re crying because you feel bad, you’re crying out of shame. You’re probably ashamed of your species.

“Beyond the gate, in the dinginess of the blizzard, perhaps you’ll try again to restore your shaken confidence in man. Without that life would be hardly imaginable.”

The death of four and a half million in Auschwitz5 and the threat of death to six million in New York. Have we really forgotten those victims already, within the first generation? Is man’s world really being shaken down to its very roots? And is one of its tiny props, the physician—just one of its many supports—trembling with it?

I don’t know if I’m a good person and a good doctor, but that’s what I want to be.

Translated from original article: Janez Milčinski, Kryzys etyki lekarskiej. Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1967.

1. The book was originally written in German and has been translated and published in an English as well as in a Polish edition. English edition: Doctors of Infamy. The Story of the Nazi Medical Crimes. Translated by Heinz Norden. (1949. New York: Henry Schuman). Polish edition: Nieludzka medycyna. Dokumenty procesu norymberskiego przeciwko lekarzom. (1963. Translated by Adam Bukowczyk. Foreword to the Polish edition by Jerzy Sawicki. Warszawa: Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich).

2. This custom has been abandoned and nowadays the name used in Polish for the concentration camp is “Auschwitz.” (translator’s note).

3. Experiments using the notorious Cyclone B (note by Zenon Jagoda, the translator of Milčinski’s article into Polish).

4. Direct allusion to lobotomy, still widely practised at the time of the article's publication.

5. Early estimates of the number of deaths in Auschwitz put the figure at four million or more. Today it is believed the death toll was about 1.1 million (translator's note).