Author

Zdzisław Jan Ryn, MD, PhD, born 1938, Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and formerly Head of the Department of Social Pathology at the Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków. Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the Kraków Medical Academy (1981–1984). Polish Ambassador to Chile and Bolivia (1991–1996) and Argentina (2007–2008). Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Physical Education (AWF) in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

World War II and the Nazi Occupation were the world’s greatest tragedy for families. Together with the imprisonment and death of millions of prisoners, an ordeal began for lonely wives, parents, and children. The death of the family breadwinner was a difficulty causing permanent material, social, and psychological consequences. The psychological situation of widows of prisoners of concentration camps comes to the foreground in this context. In Poland, there still lives a large, though rapidly diminishing, number of such persons. Widows and orphans of the victims of the Auschwitz concentration camp found themselves in the most difficult situation: they struggled to survive and adapt to the new situation. The material and social aid offered to them after the war was rather symbolic and it satisfied their basic needs only to a small extent. The families of former prisoners were not appreciated, but on the contrary, they were rather shamefully forgotten in the confrontation with the plight of “heroes,” that is, those who had died in the camps. The consequences of war and the camps become multiplied and prolonged in the plight and sufferings of widows and orphans.

In the research conducted by the author of this article, attention was drawn to the description of the psychological and social situation of widows since the time of imprisonment and death of their husbands until the present time. The time, place, and circumstances of their husbands’ arrest and, if possible, their death in the camp, were reconstructed. The psychological reactions of the closest family to imprisonment and death, the ways of adapting to the new family situation, ways of cultivating memories of the late husbands, as well as the long-term consequences to the widows’ health, were subjected to analysis (Ryn, Kłodziński 1987; Ryn 1992).

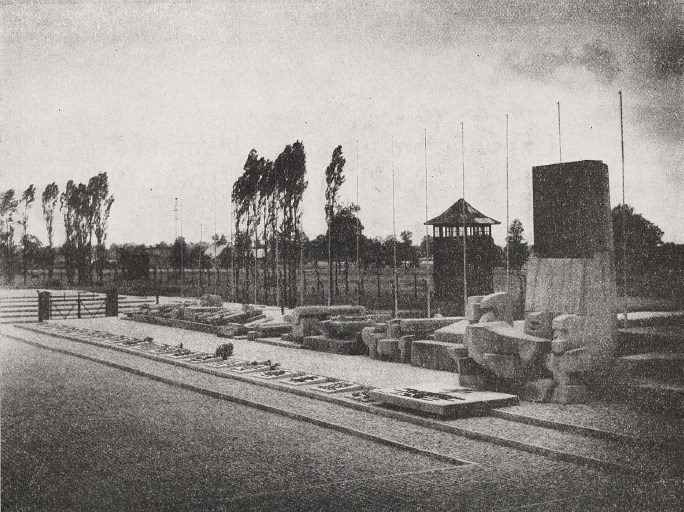

International Monument at Auschwitz-Birkenau (1968). Photograph by A. Kaczkowski

The basic research method used here was a questionnaire, which in December 1984 was presented to 215 widows of prisoners from the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, living in Krakow. By the end of 1985, 71 written replies were received (28 questionnaires were returned with information about the death of the addressee; nine widows declined to complete the questionnaire as they had married again).

Generally, the questionnaire was well received by the widows who treated it as a sign of interest in their life situation.

Personal data of the respondents

Using the questionnaire, the researcher established the basic personal data of the respondents: their age, educational status, profession, duration of their marriage, number and age of children, the date and circumstances of their husbands’ arrest, the way they were informed about their death in the camp. He also established their current social and professional status.

The age of the persons subjected to analysis ranged from 65 to 92 (the average age was 77.5 years). The duration of marriage before the arrest oscillated between 2 months and 40 years (on average, several years). Fifty-eight marriages had children, eight marriages were childless, and in the remaining cases, no data was obtained. The majority of widows (63 persons) did not remarry. Out of four persons who did remarry, two selected former prisoners of concentration camps as their partners. Among the examined widows, persons with rudimentary or intermediate level of education prevailed; persons without a profession or who were housewives. At the time of the examination, the majority of widows were retired or were pensioned as invalids (64 persons). Twenty-four widows worked part-time.

At the time of the husband’s arrest, the majority of the persons lived in good material conditions and the husband had been the only breadwinner. His arrest had quickly led to a psychological and material crisis. Mothers who were not prepared for independent life and to earn a living were in the worst situation. The nightmare of the new problems was deepened by the continual fear for their own future, the future of their children, and the plight of the arrested husband.

Reaction to the husband’s arrest

The moment of arrest had stuck in the memory of all widows as a deep psychological trauma. The day of the husband’s arrest had become a motive for celebrating on successive anniversaries, similar to the day of his death. The dominant experience from this period was fear, fright, and a feeling of powerlessness.

The following is a fragment of an account given by Helena Jordan whose husband had died in the Gross-Rosen camp, the day before the liberation of the camp:

“From the moment of my husband’s arrest, I lived under continual stress and fear, lest the Gestapo arrested me as well. For someone who did not experience it, it is impossible to imagine what fear, anxiety, and uncertainty it involved... After the news of my husband’s death had reached us, our home went dead; we all became like soulless mannequins, benumbed and not seeing any aim in further life. We lost all our interests. However, after some time, I managed to overcome my anxiety and apathy. I ordered church masses for the soul of my husband. I understood that I could not give up the struggle, that I was responsible for the future of my orphans, who did not have anyone else except me who could help them. Today, years later I realise that all those experiences, the ruthlessness, and cruelty of fortune, continual fear lest the children lose their mother, were not without influence on the nervous system of my children and myself, they also left a trace on our attitude towards life.

“The first reaction to my husband’s imprisonment was shattering and it caused a deep nervous breakdown, and even physical disturbances in my body. Deep reactive states of depression occurred, accompanied by suicidal thoughts, as everything had lost sense.”

At times, the strength of the psychological trauma was so big that you could observe a somatic breakdown: heart attacks, disturbances of the heartbeat, rapid loss of weight, diabetes, greying of hair.

The following is an account given by Janina Sieprawska whose husband died in a concentration camp in January 1942:

“There were terrible days of ordeal, sleepless nights. Life had lost its sense entirely. In the course of 4 months, I went completely grey... When I received the news about Roman’s death, I had such a serious breakdown that I stopped believing in God; if He had existed He would not have allowed such sufferings of millions of people. It lasted a long time before I regained faith...”

The day of the husband’s arrest has remained until today the most traumatic recollection, remembered in the smallest detail. These recollections may be classified as the so‑called paroxysmal hypermnesia, occurring among prisoners of concentration camps (Półtawska 1978).

In some cases, one could observe gestures of desperation or heroism, attempts to say good‑bye to the beloved person, or protest against the tormentors.

Reaction to the husband’s death

Regardless of the way of informing the person involved, the news about the husband’s death in the camp was always an overpowering shock. In most cases, the immediate reaction was despair, or more rarely one of suppression. Sometimes, one could observe attitudes of paradoxical calm and restraint.

The following are a few selected accounts. Hanna Talko-Porzecka said:

“At the beginning, I tried to convince myself that my husband was alive. I kept on inventing ways in which he could save himself, despite everything. I found various explanations why he could not send me some news about himself. There were also some people in my immediate surrounding who tried to confirm this view. Years later, I learnt that they had done that on purpose, fearing that otherwise I might have had a nervous breakdown. For I had small children whom I had to nurture and educate. Yet, after all these years, until today, the pain of this continually fresh wound has not ceased. Nothing is able to heal it.”

The following is a fragment of an anonymous account:

“Today, it is difficult to describe what I lived through and experienced then. It seemed that I would never be able to recover. When my husband died, I lost everything: happiness, joy of life, the best man; I was left completely on my own, for I had no children. Years passed but my wounds did not heal. I am still on my own, I do not mix with others. I have no contacts with other people. Today, I am an old woman whom nobody needs.”

Sometimes, the news of the husband’s death in the camp caused irreversible changes. An example may be the account given by Kazimiera Nowak, 81, recorded by her daughter Halina:

“The death record was handed in to my mother personally. When she returned home, she lost her memory. She went to bed and when she got up the following day, she was completely lost. She did not know where she was; she did not know where her husband and her children were; she did not know what day of the week it was and what the date was. It was a case of total amnesia. In addition to that, in a short time, she went white as a dove and before she had beautiful auburn hair. Since that time she had also lost her ability to write; she writes like an illiterate person.”

The above-described reactions occurred immediately after receiving the tragic news, or sometimes after a certain delay. The traumatic power of these stimuli was so great that the only defence was escape or suppression expressing itself in unrealistic states with wishful contents. Some persons needed an escape into prayer and contemplation; others, on the contrary, dramatically broke down and denied the very existence of God.

With the passage of time, these acute reactions were transformed into a protracted form and survived many years, leaving a specific locus minoris resistentiae, susceptible to new traumas in the personality of the victims.

The figure of the murdered husband often appeared in dreams. Thirty-two persons confessed to having such dreams. The dead husband appeared just as he was remembered at the time of arrest. Thus, he was young, caring, and dressed just like during the arrest.

Some widows describe the characteristic imaginings and sensual perceptions of the dead husbands. They include the psychological experience of their presence, in their home, beside their spouses. The women reported that they could talk to their husbands; they could hear their voices and answer their questions. The content of these unusual contacts was conversation or singing, in most cases of a pleasant emotional nature, as the husband usually loomed in them as a good guardian, adviser, or guide. With some widows, these experiences were superimposed on the content of dreams, in this way obliterating the boundary line between reality and dream.

The above phenomena remind one of the so-called “hallucination of widowhood,” where the widow experiences subjective contacts with the dead husband, in the shape of delusions (Olson et al., 1985). The delusions in question may be aural, visual, or more rarely, tactile in character. Sometimes, their form is more complex and includes conducting conversations. The latter phenomenon is much more common than expected, yet widows rarely discuss this problem with their physicians. They are more willing to share their feelings concerning this problem with their friends or relations (Palmer and Dennis, 1974; Kalish and Reynolds 1975; Marris 1958).

Adaptation to widowhood

Families that had had no news of their imprisoned fathers and husbands, found themselves in a particularly difficult psychological situation. Some widows continued to live in such uncertainty and expectation many years after the war. With sharpened sensitivity, they looked for any information connected with a given camp. They made contact with persons returning from those camps and, in this way, tried to trace the fortunes of their missing husbands.

Among the persons subjected to analysis, there were also widows who, despite the passage of over 40 years, still continued to believe that their husbands were alive and only for some unexplained reasons could not reveal themselves, write to them, or return home. The documents confirming the death of their husbands have no major impact on what they really feel: “I continue to hope for the return of my husband; I spend hours praying; I believe that it is not true; I believe that my husband is alive and will come back, that he will one day knock on my door. With such hopes and imaginings, I persist in prayer everyday, in chores and duties, and so the years pass.” (Jadwiga Gajda).

The choice of widowhood, despite the possibility of remarrying, was a conscious and premeditated decision on the part of the widows. The majority of them considered this state to be the only honourable expression of faithfulness to their murdered husbands. For some widows, this state was even a source of positive experience – remaining faithful to the husband, not only as a life partner, but also as a victim in the struggle for higher ideals, as a war hero. In the stories told by some widows, one could clearly detect a trace of pride from being a widow to an Auschwitz prisoner.

The most difficult period of adjustment to widowhood occurred in the first few years after the loss. General poverty and shortages of the post-war period were experienced most acutely by families without fathers. The negative attitude of contemporary authorities and state administration to members of the Home Army (Polish Armia Krajowa, AK), to participants of the Warsaw Uprising, and to members of the resistance movement, had its negative effect on their families as well. The moral wrongs perpetrated in this period have survived in memories until today.

Having children made the process of adaptation easier, as it increased motivation for life and the need of passing on war experiences to the next generation. An important psychological factor in becoming adjusted to single life was preserving an ideal portrait of the dead husband in memory. All widows underlined exceptional features of their husbands’ personalities: faithfulness, devotion to the family, ability to work hard etc. It was only in this context that the patriotic and social values of the murdered husbands came to the surface more clearly.

Memory

A common form of cultivating the memory of the late husband is a scrupulous observation of anniversaries linked with his personal life, such as birthdays, wedding anniversaries, and anniversaries of his arrest and death. Mourning masses are arranged in the memory of the dead in which entire families participate. Almost all the widows continually pray for their late husbands. The prayers are transformed into conversations with the dead husbands, and in this way, they more fully fulfil the need for spiritual contact.

Another way of cultivating the memory of the dead is by collecting souvenirs and mementoes of them, especially from the camp. Letters sent from the camp have the greatest value. For some families, they acquire the value of a talisman. The photographs from the war period are treated in a similar manner.

The majority of widows in the analysed group (42 persons) did not feel the need for visiting the camp in which their husbands died. The very thought of such a visit filled them with fear and made them feel ill at ease. Only 20 persons felt such a need and from time to time, they organised pilgrimages to the former concentration camps. The purpose of such pilgrimages was to visit the places in which their husbands were probably interned, and to lay down flowers in them. Some widows expressed sorrow that the distance and costs connected with the journey make it impossible for them to fulfil their wishes.

Consequences for health

The loss of a husband in the camp caused not only short-term disturbances, but in many instances, it led to more long-term consequences. The latter ones may be observed in personality changes and in symptoms of neuroses. Personality changes can be observed in permanent abatement of mood and of general life activity, in focusing attention on the closest relatives, and in a neurotic concern about their health and fortune. One also observes an ever-present feeling of harm and injustice; due to loneliness, abandonment, the difficulties and discomforts of life injustices, inability to experience wedded life, having children etc. One also observes an attitude of living in the past and relating all present and future situations as forms of past experiences.

Some widows explore the camp and war realities in an obsessive way. They reconstruct the conspiracy activity of their husbands and are tireless in looking for traces of their time in the camps. In this way, they tear up unhealed wounds and cause themselves new pain. They expect and sometimes even demand that those around them pity them.

Despite the passage of many years, the experienced traumas have survived among the widows in the shape of increased nervousness, fears, oversensitivity, changes of mood, depression, the feeling of having been wronged, and the restriction of the scale of feelings to matters connected with the lost person.

The selected accounts point out to a variety of health problems that have continued until today:

“Due to all these experiences, my health deteriorated. I am very nervous now; I constantly worry about my and my relatives’ future. I have completely lost the sense of patriotism that dominated my life during the German Occupation. I have periods of nervous breakdowns when I regret that life had given me such hard experiences. I believe that if my husband had survived the camp, my life would be different, better and more cheerful.” (Jadwiga Lech).

Here is a fragment of an account given by Natalia Trojanowska,

“Since the moment of my husband’s arrest I fear being on my own, particularly in the evening. This fear has made my life really difficult. I cannot go out in the evening; I cannot travel by train . . . When I feel particularly down, I take out my husband’s letters from the camp. I have 80 of them. I read them, though they are in German. After the loss of my husband, I spent 5-6 hours daily at the cemetery. I lived through every moment of our life together there. My son also recollects frequently; he says that by taking away his father, the war took away his childhood . . . The memory of my husband and his fortune has not been obliterated, despite the passage of time. It will not be obliterated for as long as my son and I live. We always remember about the victims of the Auschwitz camp who are buried at the Rakowice cemetery in Krakow. We always light candles for them. This suffering and homicide cannot be forgotten. I have lost all perspective of time. The past still lives in me and nothing has been erased from my memory. The pain has not become smaller. I pray to God fervently that our children and grandchildren do not have to experience a new tragedy – a nuclear war.”

Social implications

The Polish widows of prisoners of concentration camps did not find suitable aid and care on the part of the social and administrative bodies. This state of things had an unfavourable impact on the shaping of attitudes towards the new situation in Poland after the war. The feeling of frustration was deepened by irregularities in granting compensation to the former prisoners of camps and participants of the war, especially war invalids. The nature of this frustration is summed up by a statement made by Jadwiga Lech:

“The war destroyed everything, my dreams, my life, my home. It was a terribly brutal blow. After the arrest and death of my husband, the rest of my life was a struggle with difficulties, shortages, and human indifference. The bitterness of the situation was aggravated by people’s indifference and lack of help from the authorities after the war. It was both a moral and material blow. I regarded it as a personal blow and an injustice. The person who was closest to me, who had given his life for the freedom of the motherland, who sacrificed himself, after dying in torment was considered to be the enemy of the already liberated country. He was regarded as a useless, non-existent, and indifferent person. It was terrible. I shall never forget it. I lost all faith and confidence in the authorities.”

In this way, personal problems overlap and entwine with the social context. The need for individual remembrance is connected with the need for a communal, public remembrance. For the widow it is equally important that the society and state respect the memory of the victims. For it turns out that sometimes it is easier to bear the shortcomings in private life, as well as personal humiliation, than unjust and improper social evaluations.

Many widows learnt the truth about the conspiracy activity of their husbands only after their death. Despite the most painful loss, all of them evaluated this activity as noble and worth the price their husbands had paid and they themselves have continued to pay until the present day. The value of this sacrifice overshadows one’s own personal interest and is timeless.

In some cases, with full understanding, solidarity, and devotion the widows took over not only the burden of maintaining the family, but also continued the conspiracy activity of the murdered husbands. In this way, the widows of the Auschwitz prisoners filled in one of the most beautiful chapters of Polish and women’s heroism. In such atmosphere, the lost husband often became a mythical hero for the family.

The attitudes of many orphaned children were shaped in a similar spirit. It is not surprising, therefore, that under the influence of such ideals, the youth and even children became involved in conspiracy activities and joined the ranks of the resistance movement following in the footsteps of the beloved and glorified father. In this way, the occupants desire to crush the spirit of the nation and transform it into a nation of slaves could not be fulfilled.

The place of the murdered husbands and fathers was filled with full devotion by widows and often children. They continue in their positions until today. Unfortunately, their activity and involvement are still not perceived and appreciated. The families of the Katyń victims, of Siberian exiles, and of other victims of the Stalinist regime in Poland are in a similar or maybe even worse situation. Even the greatest effort of the authorities and the society will not be able to recompense the wrongs and losses perpetrated in this bleak period of history.

Adapted from Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1987.

References

1. Kalish R.A., and Reynolds D.K. Phenomenological Reality and Post-Death Contact. Journal Sc. Study Religion. 1973; 12: 209-212.2. Marris P. Widows and Their Families. London: Routlege and Kegal Paul; 1958.

3. Olson P.R., Suddeth J.A., Peterson P.J., and Egelhoff C.E. Hallucinations of Widowhood. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1985; 33; 543-547.

4. Palmer J., and Dennis M. A Community Mail Survey of Psychic Experiences. In Morris, J.D. (ed.), Research in Parapsychology. N.J. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press; 1974: 130.

5. Półtawska W. Stany hipermnezji napadowej u byłych więźniów obserwowane po 30 latach. Translated as “Paroxysmal Hypermnesia States Observed in Former Prisoners after 30 Years.” Przegląd Lekarski. 1978; 35: 1, 20-24.

6. Ryn Z.J. Viudas de Victimas de los Campos de Concentración Nazis: Su Patologia. Acta Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de América Latina. 1992; 38: 3, 223-228.

7. Ryn Z., and Kłodziński S. Wdowy po Więźniach Obozów Koncentracyjnych. Studium Psychologiczne i Społeczne [Widows of concentration camp prisoners: A psychological and sociological study]. Przegląd Lekarski. 1987; 44: 1, 14-34.