Author

Robert Waitz, MD, PhD, 1900–1978, haematologist, member of the French Resistance during the Second World War, prisoner doctor in Auschwitz-Birkenau (1943–1946, prisoner number 157261). After the war he became a professor of medicine at the University of Strasbourg and was Head of the Internal Medicine Clinic of the Strasbourg Municipal Hospital.

Introduction

We might wonder whether we should be talking about concentration camp survivors’ diseases in 1960, i.e., fifteen years after their release. The answer is yes: it is worth doing that for various reasons, both medical—for easier diagnoses and proper treatment of various disorders—and for those arising from daily problems related to the seriousness of survivors’ invalidity and the benefits they deserve. Although disability commissions have thousands of files at their disposal, the observations recorded in them have no significant value for statistical compilations. They only record the ailments reported by survivors, who may not be aware of the causes of their symptoms. An example is the frequent occurrence of fibrocystic breast disease, which most female survivors ignore or treat as insignificant. So, observations made by one doctor who is treating a number of survivors can be more useful.

Carrying of the Crosses. Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click to enlarge.

One reservation should be made regarding the value of data collected in this way: it does not give a true picture of pulmonary tuberculosis affecting survivors who are now being hospitalised in specialist clinics or sanatoriums if their tuberculosis is active. A patient with active tuberculosis rarely goes to see a general practitioner for treatment. This paper is based on the systematic observations of 50 female survivors. As the observations had to be carried out for a long time, I am writing only about my female patients, and disregard 250 analogous observations I have made of male survivors. Diseases follow a different course in women than they do in men.

A proper statistical analysis of the consequences of confinement in a prison or concentration camp must meet one fundamental condition: the observations should be carried out within relatively short intervals over 2–3 years. The incidence of various diseases changes rapidly—some diseases become aggravated, or new diseases may develop. Observations which have been made beyond too long of an interval are incomparable.

This condition was met, because I carried out 80% of the 50 observations over two consecutive years.

| Table I | |

|---|---|

| Year of observation | Number of observed cases |

| 1956 | 4 |

| 1957 | 6 |

| 1958 | 22 |

| 1959 | 17 |

| 1960 | 1 |

My tables do not show the onset of the disease, because I was not able to pinpoint the exact time when the disorder started. The first symptoms usually appeared just after prisoners were released, and in far fewer cases after several years. Sometimes after a period of temporary improvement, survivors’ condition gradually deteriorated. There was a noticeable period of clinical decline between 1950–1955. This was manifested predominantly in survivors who had already developed psycho-physical disorders (e.g., asthenia) by 1948–1952, which was earlier than other survivors.

The second important remark to make is that not only individual diseases show a tendency to worsen, but the number of diseases affecting a given patient increases gradually, sometimes considerably. That is why the files of the [French] Invalidity Committee are voluminous and complex.

Three factors should be considered when analysing the harmful effects of detention in prisons and concentration camps. The first is the age of the victims at the time when they were imprisoned; the other factors are the duration and place of their imprisonment, as well as the ordeals they suffered.

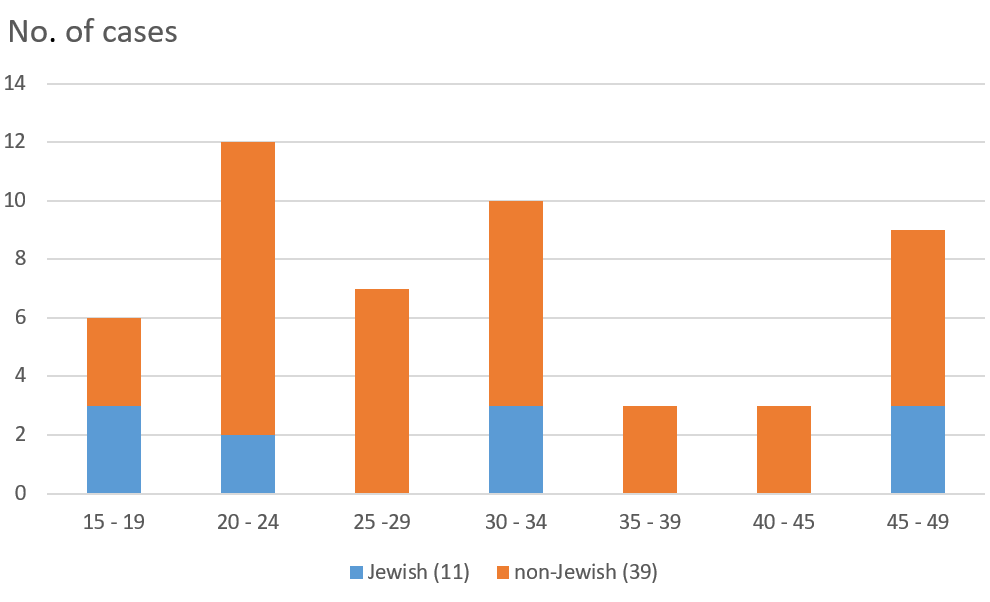

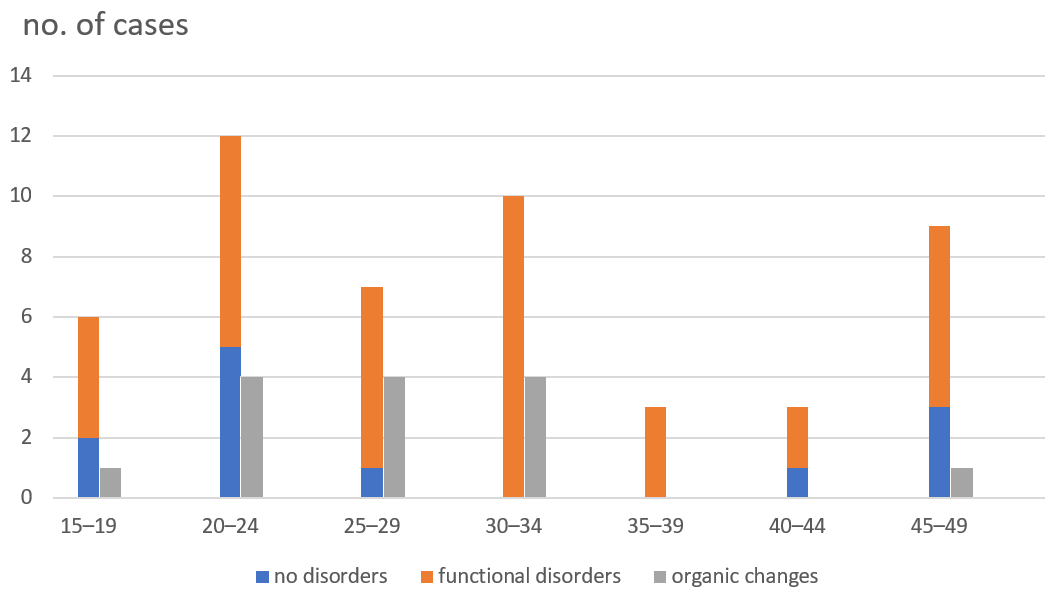

Figure 1. Age at time of imprisonment

Determining the women’s age at the time of their imprisonment will answer the question of whether there was a correlation between the appearance of symptoms and age. 35 women out of the 50 were under 35, including six who were between 15 and 19. Eleven were Jewish and 39 were non-Jewish, which must also be considered when assessing the severity of the consequences of imprisonment. The analysis of the place and duration of imprisonment shows that 45 women were detained from 1 to 18 months, and 5 for over 27 months.

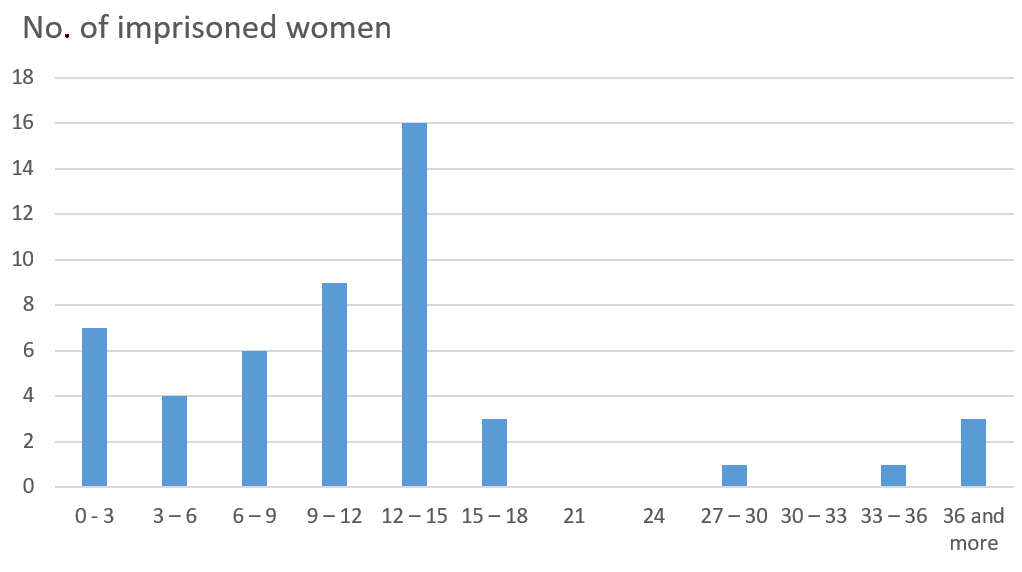

The five women who were detained for more than 27 months were either only in prison (for 2 years and 3 months; 3 years and 7 months; and 4 years) or were mainly in prison: a) eighteen months in a prison and 4 months in Ravensbrück; b) seventeen months in a prison and 8 months in Schirmeck (Natzweiler-Struthof). None of these 5 women were under 24, and none were Jewish (Table 2).

Figure 2. Duration of imprisonment (in months)

Detention in a concentration camp seems to have been much harder than in prison, where the living conditions and isolation were arduous. Also, there were more after effects for those deported to concentration camps, and they were more severe.

Finally, each observation must include a thorough analysis of the suffering experienced by prisoners during the period of their incarceration, not only the generally known physical suffering—cold, hunger, excessively hard labour, lack of rest, strenuous marches, beatings, torture—but also the moral and mental suffering. Moreover, mental suffering made prisoners’ condition far worse.

It is indeed difficult to imagine how hard these ordeals were. All of the women whose symptoms I have observed and discussed in this paper are still alive. So, I cannot describe their moral suffering in detail [to protect their privacy]. I will only mention their fear of being beaten, raped, or of attempts to rape them, of being selected for pseudo-medical experiments, or learning of the death of their families or loved ones, as well as the fear of being killed, etc.

Analysis of particular disorders

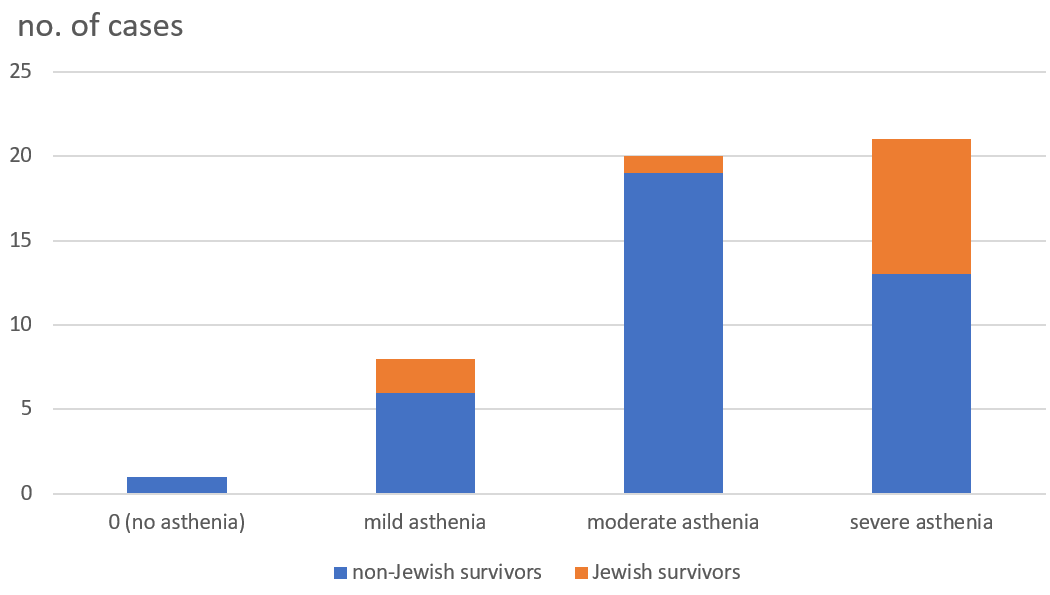

1. Asthenia

Asthenia, a term coined by Targowla,1 entails a set of neuropsychiatric disorders. I classified cases in accordance with the criteria in the guidelines issued by the French Ministry for Veterans and War Victims for the Invalidity Commission.

In patients with severe asthenia, I observed numerous cases of paroxysmal hypermnesia (nightmares, memories of torture and ordeals, concentration camps, etc.), mental disorders, [including] depression, anxiety neurosis, agoraphobia, cyclothymia, and one case of psychogenic loss of consciousness.2

I observed a sporadic occurrence (only in one woman) of a hysterical or histrionic personality and her desire for retaliation.

Figure 3 shows the frequency of asthenia in female survivors (49 cases out of the 50), the number of moderate and severe forms of asthenia (20 and 21 respectively), and as well as the high percentage of Jewish survivors among those who experienced the most severe form (8 out of the 11).

I diagnosed depression in only one woman in every 13, and mild depressive symptoms in a total of 5 out of the whole group.

Insomnia occurred on a regular basis; only one woman said that she slept well.

Headaches were very common, especially in the women with moderate or severe asthenia. There were different types of headaches: some were located in the parietal area, or others were described as a band-like sensation (i.e., tension headache) pressing on the head. I observed migraines in a few of the women survivors, which should be differentiated from sub-occipital or sub-occipital-temporal neuralgia and from neurovascular pain. Sometimes these disorders occurred in the premenstrual part of the cycle.

| Table to Figure 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| asthenia | 0 | mild | moderate | severe |

| paroxysmal hypermnesia | 0/1 | 0/8 | 10/20 | 17/21 |

| headaches | 1 | 3 | 9 | 10 |

Figure 3, with an explanatory table. Frequency of asthenia in female survivors

Two patients said they had episodes of severe dizziness, and one said she suffered from leg weakness.

One woman who lived in the country reported prolonged spells of body heat disorders (i.e., cold intolerance); she was extremely sensitive to cold and was housebound for the 8 cold months of the year. The slightest temperature fluctuations made her ill with very severe neuro-vegetative and vasomotor disorders.

2. Gynaecological disorders

These disorders were of several types:

a. Menstrual disorders during the period of imprisonment [contrasted with] the return of menstruation after liberation. Of the 50 women I observed, one was in the menopausal transition at the time of her imprisonment, 3 were pregnant, and 10 women had not started menstruating yet. Most of the women had one, two, or three [early] periods following their imprisonment. There were 4 cases the of haemorrhagic menstruation (i.e., menorrhagia). Of these 4 women, three had very heavy periods during their imprisonment and throughout their time under Gestapo interrogation.

The fourth woman had heavy periods for a whole year; she was interrogated, tortured and beaten all the time except for Sunday evenings.

46 women became amenorrhoeic during their imprisonment but resumed regular menses after liberation: in 12 cases after 1 month, in 11 cases after 2 or 3 months, in another 11 cases after 4 to 6 months, and in 5 cases after more than 6 months. Seven women had primary amenorrhea.

b. Menopause. Out of the 50 cases, 21 women experienced their menopause during the period when they were under my observation.

- One woman’s menopause began before she was imprisoned;

- 7 of the women started their menopause during their imprisonment (their age at the time of arrest was 38, 42, 44, 45, 47, 47, and 49 respectively);

-

Subsequent menopause (after incarceration)

- 9 cases of spontaneous menopause, including

- 4 cases of premature menopause:

- aged 41 (in 1945),

- aged 46 (in 1945),

- aged 47 (in 1946),

- aged 49 (in 1947),

-

and other 5 cases:

- aged 45 (in 1955),

- aged 47 (in 1958),

- aged 38 (in 1958),

- aged 48 (in 1959), and at the age of 49 in 1950.

- 4 cases of premature menopause:

- 9 cases of spontaneous menopause, including

4 separate cases occurred after surgical operations:

- aged 40 (in 1957),

- aged 44 (in 1954),

- aged 47 (in 1959),

and aged 53 (in 1958).

There were 11 cases of premature menopause on imprisonment or shortly afterwards. In 4 cases of menopause occurring soon after release, there were significant climacteric symptoms.

c. Uterine fibromas occurred in 13 cases out of the 50. The number of cases varied significantly depending on the prisoner’s age at the time of her imprisonment: 8 of the 17 women detained between 25 and 34 developed fibromas. One patient with a fibroma developed uteritis,3 another patient developed chronic adnexitis (salpingo-oophoritis), and a third developed polycystic ovaritis.4

| Table 2. Incidence of fibromas | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age at time of imprisonment | No. of cases | No. of surgeries |

| 15–19 | 0 out of 6 | — |

| 20–24 | 1 out of 12 | — |

| 25–29 | 3 out of 7 | 1 |

| 30–34 | 5 out of 10 | 3 |

| 35–39 | 1 out of 3 | — |

| 40–44 | 1 out of 3 | — |

| 45–49 | 2 out of 9 | — |

| Total | 13 out of 50 | 4 |

d. Miscellaneous. I observed the following disorders of the external genitalia:

- Vaginitis (granular)—2 cases;

- Cervicitis and polyps—6 cases;

- Salpingitis—4 cases;

and 11 cases of menorrhagia. I also observed 3 cases of ovarian cysts, 1 case of cervical cancer, 1 case of uterine prolapse, and 3 cases of hypoactive sexual desire.

e. Fertility. I wanted to determine whether detention in a prison or concentration camp affected fertility, pregnancy, and childbirth. My data show that a considerable number of women survivors who were young at the time of their imprisonment conceived and had children after being released.

| Table 3 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age at time of imprisonment | No. of fertile women | No. of women pregnant one or more times after their release |

| 15–19 | 5 | 4 |

| 20–24 | 10 | 10 |

| 25–29 | 5 | 3 |

| 30–34 | 7 | 2 |

| 35–39 | 3 | 0 |

| 40–44 | 3 | 0 |

| 45–49 | 7 | 0 |

| Total | 40 | 20 |

Out of the 20 women who did not become pregnant after release, 15 were pregnant before their imprisonment.

f. Data on the three women who were pregnant at the time of their imprisonment.

The first woman, 22, was in the third month of pregnancy and was in prison for 3 months. The delivery took place after her release in the seventh month of pregnancy. She had no more pregnancies; her child is developing normally.

The second, 21, was seven months pregnant and was kept in unheated premises for 27 days in February 1944. A month after her release she gave birth at full term. Her next pregnancy was in 1954.

The third woman (28) was four months pregnant when she and her husband were imprisoned. She was in prison for three and a half months. She gave birth one and a half months after her release, i.e. in the ninth month of pregnancy. Her baby girl had a birth weight of 2,400 g (5 lb. 5 oz.) and later turned out to have learning problems. This woman was re-arrested after her husband was sentenced. She [first] became pregnant in 1939 before her imprisonment, and after her release she conceived three more times.

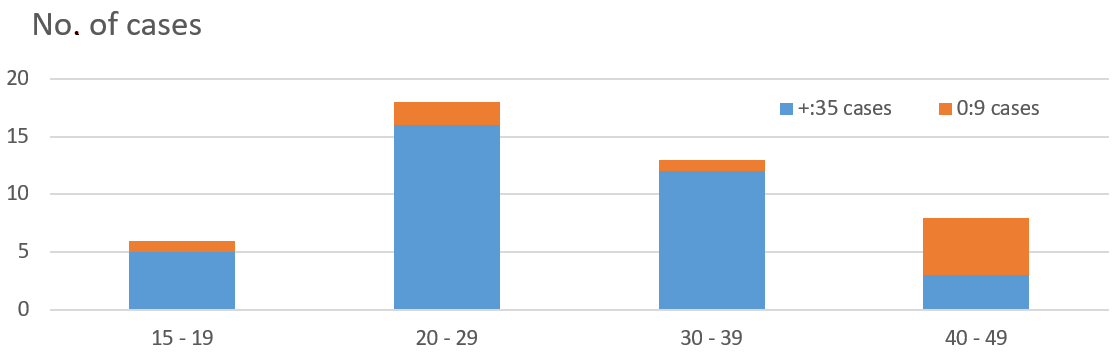

3. Fibrocystic breast disease

Figure 4 presents the incidence of fibrocystic breast disease in 44 of the women. 6 women were not examined for this condition, including 3 aged 40–49. 36 of the 44 women examined were found to have fibrocystic breast hyperplasia. There were 4 cases of unilateral breast hyperplasia (3 of the left breast, and 1 of the right breast). In 31 cases the hyperplasia was bilateral and had developed to the same extent in both breasts. In some cases, it was more pronounced on the left side. Table IV shows not only the number of cases of fibrocystic breast hyperplasia, but also the size of the changes with respect to the age of the women at the time of their imprisonment.

The cases are listed according to the status of the more hyperplastic breast.

One of the young women, who was in the 15–19 age group when she was imprisoned and was not observed to have breast hyperplasia in 1957, developed a very pronounced condition by the time she was examined in 1959. In contrast, one of the women who was over 40 at the time of her arrest had pronounced bilateral hyperplasia in 1958, which persisted in the same condition when she was re-examined in 1960.

Thus, age at the time of their imprisonment was a major factor determining a woman’s chances of developing breast hyperplasia. Other contributing factors were hyperfoliculinemia and sensitive breast tissue.5

| Table IV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of imprisonment | 0 | (+) | + | ++ | +++ | Total |

| 15–19 | I | — | I | II | — | 6 |

| 20–29 | II | I | II | IIIIIIII | II | 18 |

| 30–40 | I | II | IIIII | II | — | 12 |

| 40–49 | III | I | I | — | — | 8 |

| 9 | 4 | 14 | 15 | 2 | 44 | |

Figure 4. Distribution of fibrocystic nipple hyperplasia by age.

4. Urinary disorders

I diagnosed 8 cases of cystitis, among which we additionally diagnosed:

- 2 haemorrhagic cases,

- 2 cases with incontinence,

- 1 pyelonephritis,

- 4 cases of bladder pain,

- 2 cases of bladder prolapse (cystocele) or rectal prolapse (rectocele),

- 1 case of bladder polyps,

- 3 cases of proteinuria,

- 2 cases of renal colic,

and 1 case of renal oedema.

5. Gastrointestinal and biliary tract disorders

As Tables V and VI show, gastritis and duodenitis were quite common, especially in women who were over 20 at the time of their imprisonment. I also observed intestinal complications, such as ulcerative colitis and diarrhoeal colitis or alternating constipation and diarrhoea,6 one case of an ulcerative colitis and three cases of duodenal ulcers (viz. 6% of the group, which is a high percentage for women). Gastric and duodenal ulcers have often been observed in male survivors.

Other conditions I observed quite frequently in the group were gastrointestinal disorders which included cholangitis and biliary dyskinesia, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and haemorrhoids.

7 the 25 women who were over 30 at the time of their imprisonment developed gall stones. None of the members of their family had suffered from gall stones.

I also observed the following diseases in this group: inflammation of the lower oesophagus with a supra-diaphragmatic dilation (1 case), a diaphragmatic hernia (1 case), duodenal dyskinesia (1 case), dyskinesia of the small intestine (2 cases), peritoneal tissue inflammation (1 case), changes associated with past tuberculosis peritonitis (1 case) and inflammation of the common bile duct. Only 3 out of the 50 women had neither gastric nor hepatic disorders. Three women had [digestive disorders but] no hepatic disorders, and 5 women had [hepatic disorders but] no digestive ones.

Table VI illustrates the complexity of hepatobiliary disorders observed in some of the patients in the group. One of them, P. Z., who was 34 at the time of her imprisonment, was examined in 1958 and diagnosed with gastritis hypertrophica, inflammation of the lower oesophagus and enlargement of the supradiaphragmatic oesophagus, duodenitis, left-sided spastic colitis, hepatic parenchymal insufficiency, acute pancreatitis, and two large gallstones, one of which was the size of a pigeon’s egg. Moreover, she was also observed to have a considerable degree of biliary dyskinesia with an atonic and significantly enlarged gallbladder.

| Table V. Digestive disorders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at imprisonment | gastritis | duodenitis | diarrhoea | diarrhoea + constipation | constipation | ulcerative colitis | duodenal ulcers |

| 15–19 (6 cases) | 3 | — | — | 1 | 3 | — | 1 |

| 20–29 (19 cases) | 12 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | — | 1 |

| 30–39 (13 cases) | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 1 | — |

| 40–49 (12 cases) | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | — | 1 |

| Table VI. Hepatic and biliary disorders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at imprisonment | hepatic failure | enlarged liver | biliary dyskinesia | cholecystitis | cholelithiasis | pancreatitis | haemorrhoids |

| 15–19 (6 cases) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | — | 3 | 3 |

| 20–29 (19 cases) | 16 | 1 | 5 | 1 | — | 5 | 1 |

| 30–39 (13 cases) | 7 | — | 7 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| 40–49 (2 cases) | 6 | 2 | 5 | — | 5 | 3 | — |

6. Respiratory disorders and tuberculosis

I diagnosed inactive pulmonary tuberculosis in 5 of the 50 women I examined, but only one had calcified nodules (granulomas).7 The remaining women with inactive tuberculosis were 16, 31, 34, and 44 when they were imprisoned. There was one case of peritoneal tuberculosis (age at imprisonment: 23).

Thus, 4 of the 5 women with pulmonary tuberculosis had been imprisoned when they were over 30.

However, we might think that especially the younger prisoners should have contracted lung diseases. They did in fact, but many of them died of tuberculosis in the camps.

As I have already emphasised, these data have no statistical value. Active tuberculosis is usually treated in sanatoriums and specialist wards. Nonetheless, my observations may still be relevant. In the majority of cases of female survivors with pulmonary tuberculosis, it is impossible to observe a complete cure. Their X-rays hardly ever showed fibrotic scars or calcified nodular lesions (calcified granulomas). That is why invalidity commissions should be extremely cautious in diagnosing full recovery from pulmonary tuberculosis, since latent infection can re-activate around these uncalcified nodules.

As regards nonspecific respiratory diseases, two observations need to be made: a high level of sensitivity of the upper respiratory tract (4 cases; the oldest woman was 28 at her imprisonment) and bronchitis, with 4 recurrent cases (in women aged 16, 18, 19, and 28 when they were imprisoned), and 3 chronic cases (age at the time of imprisonment: 22, 25, and 26).

In addition, there was one case of each of the following: cirrhosis of the lung, pleurisy, and acute emphysema (in a young woman who was 17 when she was imprisoned).

7. Cardiovascular disorders

In the group of female survivors I examined, there was a high frequency of cardiovascular disorders.

Figure 5 shows the incidence of cardiac disorders. The following comments may be made on the data:

- Frequency and intensity of functional disorders. Pain, sometimes very sharp, in the heart area, exertional dyspnoea, arrhythmia, etc., are often indicative of an anxiety syndrome known as cardiac neurosis.

- High blood pressure.

- I often observed moderately high blood pressure in women who were over 20 at the time of their imprisonment, along with a reduced amplitude,8 which is significant for the subsequent development of cardiac disorders (hypertension, heart failure, etc.).

- b. Occasionally I also observed significant hypertension in some of the women who were over 25 at the time of their imprisonment.

- Frequency of structural changes, usually rheumatic9 or atherosclerotic, and sometimes mixed. They occurred mainly in women who were under 35 when imprisoned.

- Rheumatic lesions of the mitral valve—5 cases;

- Mitral valve and aortic lesions—4 cases:

- rheumatic—3 cases,

- atherosclerotic—1 case;

- Aortitis—3 cases (one case with atherosclerotic lesions);

- Myocarditis—1 case;

- Coronary vasculitis—1 case;

- Numerous cases of varicose veins regardless of age at the time of imprisonment—only two of the women concerned had varicose veins before being sent to the camp, and their condition aggravated in the camp. 13 cases of varicose veins, 8 cases with both legs affected, and 5 cases of unilateral varicose veins. 1 case of phlebitis.

-

Vascular disorders:

- acrocyanosis or erythrocyanosis—2 cases;

- vascular disorders of the limbs—2 cases;

- swollen feet, ankles, and legs (oedema)—5 cases.

Total: 14 cases

| Table VII | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of imprisonment | blood pressure | |||

| normal | low | high | ||

| slightly high | very high | |||

| 15–19 | 5 | 1 | — | — |

| 20–24 | 7 | 2 | 3 | — |

| 25–29 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| 30–34 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 35–39 | — | — | 2 | 1 |

| 40–44 | — | — | 3 | — |

| 45–49 | 1 | — | 2 | 6 |

Figure 5. Cardiac disorders

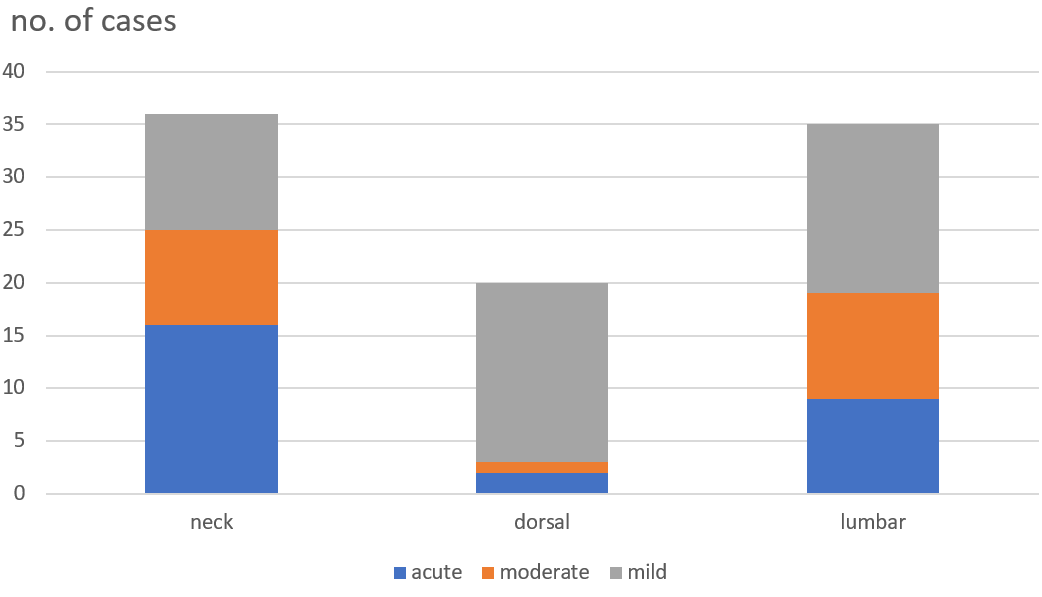

8. Rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarticular complications

I observed a high incidence of:

a. acute rheumatoid arthritis,

b. deforming and non-deforming rheumatoid arthritis,

c. mixed conditions,

d. periarticular arthritis.

a. Acute arthritis. Its acute character comprised:

- persistent pain and other clinical ailments impairing functional and occupational performance, and an impaired ability to sleep due to pain; uncomfortable insomnia, which is very common in survivors;

- many large and small joints, especially in the spine, involving two or more segments and showing a tendency to develop subsequent degenerative changes, often very resistant to treatment. In 16 out of the 50 women, these changes involved spinal disks, in 3 cases they affected several vertebrae. In addition, there were deformities in the sacroiliac joint, often with spondylolisthesis;

- sciatic, cervico-shoulder, and sub-occipital nerves could also be affected, sometimes mimicking neurovascular or (less often) intercostal pain.

Hence, an X-ray should be taken of the entire spine, especially of the neck, and carefully examined. Oblique views should be taken of the atlantoaxial joint (the C1 and C2 vertebrae) and of the L5 to S1 lumbosacral section. I looked for displacements. Bone spurs osteophytosis on the spinous processes occurred less frequently.

b. Deforming arthritis is a fairly familiar condition [in survivors] and is sometimes compared to premature age-related or microtraumatic deformities.

The guidelines issued by the [French] Ministry [for Veterans and War Victims] put special emphasis on these conditions and established recommendations. However, it is a pity that many specialists tend to emphasize the lowest incidence, or combine distant joints as one [symptomatic] group [when they assess the disability pension a survivor may claim thus diminishing the grounds her injuries].

c. Non-deforming arthritis is usually not listed in the Ministry’s guidelines and [is erroneously] ignored by specialists. While early X-rays show only a minimum change in this respect, specialists believe that non-deforming arthritis is only a subjective ailment.

Figure 6. Deforming arthritis

| Table VIII | |

|---|---|

| Acute forms of rheumatoid arthritis | 35 cases out of the 50 |

| a. severe rheumatoid arthritis deforming arthritis – with dislocated vertebrae – painful and hypersensitive – inflammatory | 18 8 10 1 1 |

| b. mixed forms deformation + pain deformation + inflammation ankylosing spondylitis + pain +inflammation | 15 6 7 1 1 |

The most common types of non-deforming arthritis I observed in the group of 50 women survivors were as follows:

- Various forms of inflammatory rheumatoid arthritis: 6 cases of mixed spondyloarthritis, 3 cases of acute, often masked rheumatoid arthritis, arthritis complicated by infection (e.g., scarlet fever, etc.), rheumatoid polyarthritis, and inflammatory arthritis syndromes which are difficult to classify.

In various forms of inflammatory arthritis, the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate was not always elevated. - Painful polyarticular arthritis tended to be generalised and accompanied by symptoms of depression. I observed 14 cases of joint pain, more often mixed forms.

- Periarticular unilateral or bilateral inflammations of the shoulder area were common (13 out of the 50 women suffered from them); this condition led to functional impairment.

The causes of these disorders were the same as for infectious arthritis. Other contributing factors included Gestapo interrogations and violence, the victim being slung up by the arms and left in a hanging position, especially if her arms were tied behind her back. Cases of arthritis involving the hip joint were not so common.

d. Mixed forms were characterised by combinations of deforming and inflammatory types, or deformations with painful and inflammatory arthritis. Similarly, other inflammatory forms could also be combined. These mixed forms were particularly severe and led to considerable disability.

e. Periarticular arthritic changes: tendon-synovial, muscular, pertrochanteric femoral changes, etc.

f. I observed a number of different conditions in the 50 women which deserve to be mentioned: calcifications in the sacroiliac tendons, soft-tissue shading beyond the process due to a fracture, dislocateddisplaced vertebrae, thoracolumbar sclerosis, and fallen arches (3 cases, in one of them, the deformation led to a flat foot).

g. Changes caused by arthritis were frequent. I did not observe any arthritic changes in 4 of the 50 women. At the time of their imprisonment, these 4 women were 16 (with severe scoliosis), 17, 23, and 44.

h. Arthritic symptoms have occurred at various times since the women’s release, shortly after their liberation or later. Their condition has clearly deteriorated over the past two to four years.

i. Age at the time of imprisonment did not have much of an effect on the clinical condition and its severity. It was only significant to a certain extent in the case of osteoporosis. Age had no effect on the development of scoliosis, which I saw in 13 cases, including one case of deteriorating juvenile scoliosis.

| Table IX | |

|---|---|

| Age at imprisonment | No. of osteoporosis cases |

| 15–19 | 1 out of 6 |

| 20–24 | 0 out of 12 |

| 25–29 | 1 out of 7 |

| 30–34 | 2 out of 12 |

| 35–39 | 0 out of 3 |

| 40–44 | 0 out of 3 |

| 45–49 | 5 out of 9 |

i. This report shows just how insufficient the medical examination for the assessment of disability is, and the difficulties encountered by the Medical Consultative Commission of the Ministry for Veterans and War Victims. The following points should be clarified in the Ministry’s guidelines to avoid unfair assessments of survivors’ health, and the following actions should be taken:

- pay special attention to the advancement and progress of disorders of the spine and limbs;

- make a distinction between deforming, inflammatory, and painful arthritis; a combination of two forms increases the degree of disability;

- remember that there is little or no X-ray evidence for inflammatory arthritis (osteoporosis, etc.).

9. Endocrine disorders

I observed:

- 12 cases of goitre: 9 cases of struma diffusa (diffuse goitre), including one case of calcification; 1 case of struma nodosa (multinodular goitre), 3 cases of struma basedowiana (Graves’ disease);

- the Chvostek sign was observed in 3 cases;

- 1 case of polyglandular deficiency;

- one case of hirsutism, and

- 1 case of cold sensitivity.

The hypothalamus and autonomic nervous system play a significant role in all of these disorders.

10. Nutritional disorders

These disorders occurred in numerous cases:

- emaciation—8 cases;

- obesity—17 cases, including two dating from before imprisonment; considerable obesity in half of these cases, extreme obesity in a few and overweight in the other cases;

- cellulitis—5 cases;

- hypercholesterolemia over 240 mg%—13 cases out of 33 examined; high uric acid level in the blood—11 cases out of 33 examined.

11. Miscellaneous

- 3 cases of syphilis were observed in 1945, 1946, and 1947. This observation is quite significant, 3 out of the 50 patients—is similar to the percentage of non-sexually transmitted genital tract infections. Out of these three cases two were due to prostitution, and the third to rape.

- 5 cases of myositis—1 case of inflammation of the pectoralis major muscle, which was first diagnosed as angina pectoris, but turned out to be an inflammatory infiltration of the edge of the pectoralis major muscle. The remaining four cases represented thigh muscle inflammation. The clinical picture was the same: pronounced thigh fatigue during exertion, especially when going upstairs; the need to stop for a few seconds, intermittent claudication with unchanged pulse and oscillometry of the legs. If a patient with this condition moves her thigh to a position perpendicular to her pelvis, she cannot move her leg back into a straight position even though the movement is usually painless. This symptom is caused by a shortening of the posterior thigh muscle. It is not a limitation of mobility due to pain, as in the case of Lasčgue’s sign. J. Silber of Metz and I observed painful thigh muscle contractures in many of our colleagues at Budy-Manowice concentration camp in winter. But they concerned mainly the adductor muscles.

- Consequences of injuries (4 cases), frostbite (3 cases) and typhus (one case).

- 3 cases of severe allergies that developed after the patient’s return from the concentration camp.

- 3 cases of leukopenia and granulocytopenia, one of which was anaemia-related.

12. Reactions of the women survivors to abnormal conditions

Both male and female survivors tend to react to their environment in a different way from other people. Although this has hardly been taken into account, it should be included in the assessment of survivors’ disability. At this point, I cannot give details, because the examined survivors are still alive [and their confidentiality needs to remain protected]. I can only briefly highlight certain facts:

- acute and prolonged depression following [professional or personal] failures;

- depression caused by the death of the survivor’s husband, requiring a long period of treatment in a sanatorium;

- “sponge-like” obesity, with a weight gain of 20 kg occurring in the space of two months after the sudden death of a child;

- acute forms of anxiety observed in some cases, especially the anxiety of becoming pregnant, because the survivor’s first pregnancy on her return from the camp led to psychological imbalance and neurosis;

- cardiovascular dysfunction, sometimes very acute and resistant [to treatment], which occurred after a hysterectomy due to fibroma.

It is impossible to predict how survivors will react psychologically to somatic exertion, infectious diseases, surgeries, or even minor mental shocks.

***

Translated from the Polish: Waitz, R., “Zmiany chorobowe u bylych wiezniarek obozów koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1963. Originally published as “La Pathologie des déportées.” La Semaine des Hôpitaux, 1961.

- The French psychiatrist René Targowla.a

- An involuntary reaction of the brain to distress which can occur in individuals subjected to trauma.b

- The term “uteritis” has been preserved after the original; however, it is much more probable that the condition in question here is the much more common endometritis, i.e., inflammation of the inner lining of the uterus (endometrium).a

- The modern term is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).b

- The term “fibrocystic breast disease” has fallen out of use in favour of “fibrocystic breast changes” or simply “fibrocystic breasts,” as the condition is entirely normal (with more than half women experiencing it at some point of their life) and cannot be considered a disease.

Additionally, the term hyperfolliculinemia is not used to describe a clinical condition and is now considered a controversial concept; nor can it be considered a contributing factor here.

The exact mechanism of the condition described by the author is not fully understood, though it is known that breast tissue responds to hormone levels.a, b - The author may be referring to what is now known as the irritable bowel syndrome, which is characterised by alternating constipation and diarrhoea.b

- Inactive, past tuberculosis usually presents as pulmonary nodules in the hilar area or upper lobes, with or without fibrotic scars and volume loss. Nodules and fibrotic scars may contain slowly multiplying tubercle bacilli with the potential for future progression to active tuberculosis.a

- A “reduced amplitude” is not considered a separate risk factor for the development of hypertension or heart failure.b

- Rheumatic fever is an inflammatory disorder caused by a Group A strep throat infection. It affects the connective tissue of the body, causing temporary, painful arthritis and other symptoms. In some cases, rheumatic fever causes long-term damage to the heart and its valves. This is called rheumatic heart disease. In chronic rheumatic heart disease, the mitral valve alone is the most commonly affected valve in an estimated 50–60% of cases. Combined lesions of both the aortic and mitral valves occur in 20% of cases.a

a—notes by Maria Ciesielska, MD; b—notes by Susan M. Miller, MD.