Author

Ella Lingens-Reiner, MD, JD, 1908–2002, Righteous Among the Nations (1980), survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau (prisoner no. 36088) and Dachau, witness in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials (1964).There were two kinds of resistance against Nazi German terror. One was the organised kind. Organised resistance groups had to use every means they could, legal or illegal, to destroy the enemy and sabotage his undertakings. But there was also another method of resistance, a quiet way, saying a distinct “no” on the basis of steadfast defiance. The resistance offered by every individual who refused to be dragged in and turned even into the smallest cog in the machine of destruction had an immediate practical value. Behaviour of this type set a moral example which had a deep and far-reaching effect and deserves special esteem, because it sowed the seeds of new groups of resistance.

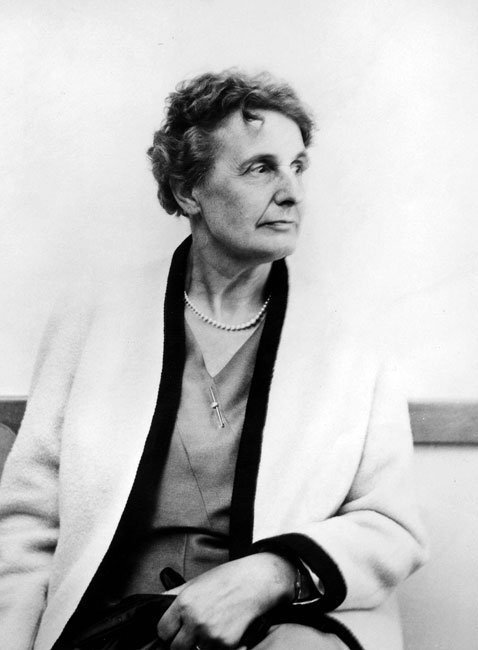

Dr Adélaïde Hautval was one of the persons who jeopardised her own safety to make a personal contribution of this type of quiet resistance. A physician who survived the women’s camp at Auschwitz- Birkenau, Dr Hautval is now working as a medical practitioner for the schools of Paris.1 She set a fine example for others to follow.

When I arrived in Auschwitz in February 1943, as a German non-Jewish doctor, I was sent to Block 22, the German hospital block. Right after we arrived, when we were still in the “sauna,” Scharführer (or Oberscharführer) Klauss said to me, “It’s a good thing we’re getting a German doctor for the German prisoners. At the moment there’s a Frenchwoman, and all she says is ‘oui, oui,’ and ‘grippe,’2 while the women are going down like flies. You must look after the patients in the hospital as if they were your private patients.”

As a new arrival with no knowledge as yet on the situation, I let myself be fooled by his polite words of address and clearly patronising tone, and thought that since the SS had such an attitude full of care for sick inmates, things could not be as bad as I had feared. I did not yet know the truth about Auschwitz.

Next, I toured the camp and the hospital. I had just arrived from the clinics of Austria, with their white-tiled walls, and I was shocked by what I saw. It was like being knocked on the head with a hammer.

I staggered about helplessly between the beds in a windowless stable. I could barely make out the faces of the patients in the dingy block, and I couldn’t hear anything for the noise made by the women crowded together in the narrow corridor. How was I supposed to auscultate a patient in such conditions? Trying to keep my balance between the three-tier bunks, I would not be able to administer an intravenous injection, and I wondered how I would be able to reach and examine the woman at the back, next to the wall. It would be extremely hard to carry out any medical observations at all.

And then I saw a tall, slim, dark-haired woman of about 30 with the regular, worthy features of a Roman lady, calmly and confidently passing from one patient to the next. She administered an injection to one patient, then applied a dressing to another patient, and all the time had a kind word of comfort for each of them. She did all her tasks with ease, while I found them difficult. She looked after me in a kind and friendly way, helping me, her junior colleague, and explaining the range of duties to me. With unwavering confidence she showed me where to administer an urgent infusion, where to inject strophanthin to prevent the worst. The few medications available were administered to those patients whose lives were at risk. Every decision she made, each of her orders was precise, well thought out, and made perfect sense. The idea to stand up against her would not have come into anyone’s mind. Nonetheless, of course, the women still continued to drop like flies, because of typhus. However, the only diagnosis that the SS physician heard from Dr Hautval was “flu,” because she knew that a diagnosis of typhus would have meant a lethal injection or gas chamber for the patient.

One day, Dr Mengele ordered us prisoner doctors to draw up a list of diagnoses and prospects for all the women patients in the block, and although it was an order that did not suffer disobedience, yet she dared to refuse. “He’ll use this list to make his selections. I’m not going to do it,” Dr Adélaïde Hautval said. And she didn’t.

As soon as I had recovered from typhus, Dr Rohde, who was our SS physician at the time, transferred me “for a rest” to Block 10, the experimental block in the men’s camp. I didn’t have to be an experimental guinea pig; nor was I required to do any other type of work. I could spend a couple of weeks in bed, in the orderlies’ room, which was relatively clean in comparison with the conditions in Birkenau, until I had fully recovered. After a few days Dr Hautval was sent to the same place, too. One day unexpectedly, the garrison physician called her and asked if she could operate. She said she could, and straightaway she was sent to work in Block 10.

I didn’t ask her what kind of operations she was to perform here, and she never mentioned the subject. She was just as calm and resolute here as she had been in Birkenau. On the other hand, I was still so dazed by my illness that I didn’t realise what was going on around me.

After a few weeks I was transferred to Babitz,3 and in late August Dr Rohde sent me back to work in the Birkenau women’s hospital, which had been expanded in the meantime. Here I again met Dr Hautval.

“You’re not on Block 10 any more?” I asked.

“No,” she replied.

“Why were you laid off?”

“First I had cases which needed an operation, so I operated them. But later women were sent to me with no medical indications calling for surgery, and that was too much for me. I said I would no longer operate.”

“And what did Dr Wirths say to that?”

“Nothing, he just sent me back here.”

Was it possible for a prisoner to refuse to do what she was ordered to do and get off scot-free?

Last autumn I met Adélaïde Hautval again, after nearly 20 years, for the first time since Auschwitz. We were in a cosy apartment with two pianos and an accordion. Alongside her professional work, Adélaïde loves music and on Sundays she plays the organ in her parish church. Only now did I learn what had really happened back then in Auschwitz.

Dr Hautval reported in the garrison physician’s office and told him she would not conduct the operations she had been ordered to do, because it would be against the Hippocratic Oath and against her conscience as a doctor.

“But you’re only to operate on Jewish women,” Dr Wirths replied.

“Nonetheless, I still don’t see any reason to change my mind on the issue.”

Wirths had a vague feeling that although it was easy to force a prisoner to dig their own grave, it would be hard to force them to perform an abdominal operation and get them to do what Wirths wanted. It would be easy for the operating surgeon to sabotage the job. So he tried another way to persuade Dr Hautval.

“Yes, so you don’t at all think that there is a difference between people?” he asked.

“Oh, but I do, Herr Hauptsturmführer,” answered Dr Hautval. “I think there’s a tremendous difference between people, for instance between you and me.”

Wirths made no reply to that, but just sent her back to Birkenau.

At first nothing happened. But one evening after a few weeks Orli Reichert, the camp senior, called Dr Hautval.

Orli was very distraught and said, “Adélaïde, I’ve been notified that tomorrow morning you’re to be put on a transport. Executions are due to be held in the men’s camp, and you’re on the list. But we’re going to do all we can to save you.”

Presumably Wirths had informed Berlin the order had not been carried out, and Berlin had issued a death sentence.

“Thank you,” Adélaïde said to the camp senior and went back to the block, where she carried on with her work as if nothing had happened. She didn’t tell anyone about her talk with Wirths, and none of us sensed that she had been sentenced to death. Next morning she was waiting for them to take her away. But the day passed and nothing happened. Nothing happened on the day after that, either.

Over the next few weeks she knew that any day could be her last. All the time she calmly and unostentatiously continued to do her job. No-one noticed anything, either.

“Finally,” she continued her story, “I was transferred along with hundreds of other women to a small sub-camp next to a factory. I was hoping they’d forget about me. And indeed, I managed to survive until the day of liberation. I still have no idea why I was not executed.”

Orli is no longer alive, so we can’t ask her. Could she and her friends in the men’s camp have been so influential that, for instance, they could swap Adélaïde’s camp number for the number of a deceased prisoner? Could the SS have overlooked the matter, because Dr Hautval was the only one to be taken away from the women’s camp? Were they in such a hurry that they missed her? Could it be that, given a bit of good luck, the SS’s corruption or sluggishness saved her life? Or should we believe in a miracle, that her unparalleled courage and powerful personality could have made the SS-man who was to carry out the order decide not to carry it out, thereby saving this woman’s life? Dr Hautval could not have counted on any of these things happening, and had resolved to face all the consequences of her behaviour.

Shouldn’t this be read by all those who are still hedging and denying their responsibility with the excuse that “they were only carrying out orders”?

Translated from original article: Lingens-Reiner, E., “Dr Adelajda Hautval.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim; 1964.

Notes- The article was published in 1964.

- French for flu.

- A sub-camp of Auschwitz established in the village of Babice following the eviction of the villagers.

Notes by Teresa Baluk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator of the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland.