Author

Artur Metera, MD, pulmonologist, contributor to Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.

Wit Maciej Rzepecki, MD, PhD, 1909–1989, cardiothoracic surgeon, during the Second World War served as a military surgeon for the Polish Armed Forces in the West. Former Head of the Zakopane Chest Surgery Clinic.1

Today thoracoplasty is no longer a major collapse therapy for the surgical treatment of fibrous-cavernous pulmonary tuberculosis.2 More and more operations are being conducted with more and more advanced techniques to resect lung tissue, preceded by the right chemotherapy, and have brought about a considerable reduction in the indications for thoracoplasty. But even at the time when thoracoplasty was one of the basic methods applied in surgical treatment, the indication for its use was clearly defined—a tuberculous cavity (Talewski).

The general opinion was that for the tuberculous cavity to heal, it had to be closed off at the unobstructed draining bronchus, which could be achieved using collapse therapy, and one of the ways this could be done was by thoracoplasty. As tuberculous cavities tended to be located in the top segments of the upper lobe, thoracoplasty was usually performed in the superior, rather than in the inferior area. The latter type was done much more rarely, for a cavity in the sixth segment. Full thoracoplasty was rare as well, since it was extremely hard on the patient because of its extent, the associated hypovolemic shock caused by a heavy blood loss, and respiratory impairment caused by the compression of the lung, paradoxical breathing, and diaphragmatic dysfunction. Thoracoplasty involved another risk, postoperative infection of the wound and exudate following apicolysis. In view of the large area of the surgery, this was an additional counter-indication, especially before the advent of antibiotics, making doctors think twice before they embarked on thoracoplasty.

Our aim in this article is to present the issues involved in operations of this type, as performed on prisoners in Dachau concentration camp. We are going to discuss the case of one of these prisoners, on the basis of his own account.

Patient W. J., aged 46, was hospitalised in the Zakopane Chest Surgery Clinic in November and December 1969 (hospital record No. 494/68) for treatment and a check-up following a full thoracoplasty performed in 1941 in Dachau. In his interview, W. J. said that he was arrested in May 1940, when he was 17, handed over to the Gestapo and sent to Auschwitz on 14 June 1940, where he was registered as No. 402.3 As we know, the sanitary conditions in Auschwitz were very bad. For instance, one hand-operated water pump had to cater for about 750 persons, prisoners had to sleep on the floor, three to a mattress meant for one. Prisoners worked 10–12 hours a day, on hard labour out of doors right into the late autumn, wearing only the standard striped prison gear. Their daily food ration amounted to 1,400 calories with a very low protein content. Many prisoners could not endure such conditions and died.

W. J. fell sick in November 1940. He had spells of dizziness and muscle pain, but no cough. He counts himself lucky, because one night during the evening roll call the Lagerführer4 took a look at his tongue and sent him to the camp hospital (Fejkiel, Münch, Olbrycht, Paczuła, Höss, and Zielina). At this time no prisoner-doctors were working there yet. No lab tests were done, either. Aspirin was the only medication dispensed. W. J. stayed in hospital for about a month. He had his temperature taken only once. Next, he was sent to the convalescence ward, and afterwards went back to work. He is 179 cm (5 ft. 9 in) tall, but his weight at the time was 48 kg (105 lbs.). In March 1941 he went to see the doctor again, and this time he had an X ray taken. He says that he was told that “there was something there,” but was not sent to the TB ward.

In June 1941 he and a few other young prisoners were evacuated to the TB ward in Dachau, where he was registered as No. 26137 on 3 June 1941 and admitted to ward A in the tuberculosis station (Musioł).5 Prisoners designated for surgery had fairly good living conditions. W. J. was X-rayed. His ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) was 72 (average of 2 readings). He had several sputum tests done for TB, and one of them was positive. He learned of his condition only by reading his temperature chart. A week before the operation three officers saw him, but did not examine him. On the day of the operation he was not given breakfast and took a bath. He thinks the operating theatre was quite well equipped. He had general anaesthesia (Evipan6 and chloroform) administered for the operation which was performed by Dr. Müllmerstadt.7

The first phase of the thoracoplasty operation was carried out in July 1941 and lasted about one and a half hours. Five or six of W. J.’s top ribs were removed. Post-operative care was given by prisoner-nurses. The only medications W. J. received were painkillers. He had a layered dressing put on the wound, but cannot say whether it was a compression dressing. For two days he was on a special diet consisting of a dense milk soup sweetened with sugar, butter, noodles with butter, and two eggs. A doctor only came to see him after two or three days (Wolny). W. J. remembers about ten phase one thoracoplasties conducted on other prisoners. Three died during the operation, and a couple of them died in the ward.8 W. J.’s wound healed with no complications.

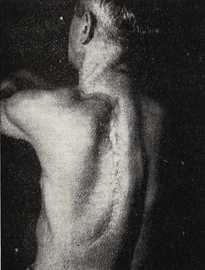

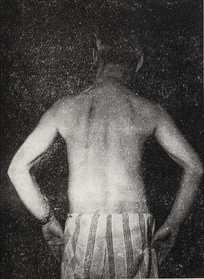

Photo 1. W. J.’s postural deformity following thoracoplasty in Dachau concentration camp. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1971.

His phase two thoracoplasty was done six weeks later. He had a total of eleven ribs removed in the two surgeries. He remembers there were four other patients who were operated a second time. The post-operative nursing care, diet, and treatment was the same as after the first operation. The ward and their bed linen were kept clean, though there were patients with an infected wound and others who had just had their operation in the beds next to them (Wolny). Four weeks after W. J.’s second operation, his wound started to discharge an exudate and had to be opened under general anaesthesia. It took a long time to heal—until December 1941. Afterwards, W. J. was discharged from the hospital and sent back to work. Thanks to the efficient work of the prisoners’ clandestine mutual assistance group, he was given a light job, first in the stocking and sock darning unit, and later in the garden (Musioł). Two years later W. J. was back in the TB ward with a cold (by that time there was no longer a TB station). He was X-rayed, but no treatment was prescribed. He had a sputum test done for TB using the direct method, and it gave a negative result., W. J. never had any complications after the liberation of the camp until 1956. In 1956 he reported to an anti-tuberculosis clinic and spent four periods of treatment in a sanatorium and was also hospitalised in the Second Internal Diseases Clinic of the Warsaw Medical Academy.9

On examining W.J. at the Zakopane Chest Surgery Clinic in 1968, we observed the following: general condition: good. Posture: distorted, with scoliosis in the chest area on the left side of the spine. Breathing: dyspnea (shortness of breath) at rest. Cardiovascular condition: stable. Chest X ray (posteroanterior view): right-hand side—several small patches of shadow distributed over the entire area of the pulmonary parenchyma; left-hand side: post-operative condition following thoracoplasty for the removal of 11 vertebrae. Numerous small patches of shadow and discrete calcifications visible in the pulmonary parenchyma. Tomography (posteroanterior view): left-hand side—streaks of shadow in the apical area, best visible in the 8 cm layer. In addition, inhomogeneous shadows and calcifications visible in the apical part of the parenchyma. A few calcifications visible along the periphery of the central area. General spirometry: vital capacity (VC) 2490 ml (25% of the normal value); forced expiratory volume (FEV) 1440 ml (59% of the normal value); maximum voluntary ventilation (MVV) 55 litres (49% of the normal value); breath reserve (BR) 44.2 litres. A considerable extent of respiratory failure of the mixed type, with predominant restriction. Bronchospirometry: the left lung contributes 34% to the patient’s respiration. ECG: heart axis at the top end of the normal range. Blood morphology: normal. Urine test: a trace of protein; 3–4 leukocytes10 and 25 erythrocytes11 visible in the sediment.

Photo 3. W. J.’s X ray after the thoracoplasty of his left side. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1971.

As we know, during the Second World War there were very many physicians in the Nazi German concentration camps who exploited these places as testing sites to conduct criminal experiments on human beings. We shall recall the experiments Dr Heissmeyer conducted, infecting children and adults with TB in Neuengamme concentration camp (Kłodziński);12 the Ravensbrück surgical experiments (Mączka; Półtawska); and the low-pressure chamber in Dachau (Mączka; Musioł).13 These are well-known facts, and have received extensive coverage in the research.

This article is a contribution to the history of the tuberculosis station that operated in Dachau in 1941, and especially its ward A, which was a place where TB was treated with calcium, codeine, and pheumothorax or thoracoplasty. In ward B, patients were under observation but received no treatment. The therapy in ward C consisted of outdoor walks and exercise, while ward D administered homeopathic cures to its patients. Dr Rudolf Brachtel was chief physician.14 The TB station was closed down in 1942, and the overwhelming majority of its patients were gassed in Hartheim (Musioł).15 Drs Müllmerstadt and Lange16 performed surgical operations, often neither having any indications for the surgery nor having examined the patient beforehand (remarkably, the X rays were done for them by a prisoner who was a carpenter by profession—Musioł). According to W. J., sometimes they treated an operation as a type of punishment for the operated prisoner; sometimes they raced each other who could operate faster and bragged about it (Wolny). They took care to have the wards kept clean, using draconian punishments, such as hanging up by the arms, against those who broke their rules; yet at the same time they had post-operative patients straight after surgery in beds next to patients with oozing inflammations (Wolny and W. J.).

We don’t think the thoracoplasty performed on W.J. could have been part of a pseudo-scientific experiment, as the SS physicians did not show very much interest in this patient’s condition either before or after the surgery. However, the extensive thoracoplasty they decided to conduct and performed without much consideration put the patient at risk from a serious and presumably unnecessary operation. No attempt was made to try pneumothorax, which would have been a far less radical treatment. There is no evidence in W. J.’s X rays of a healed tubercular cavity, yet the surgery was carried out on a man who was debilitated, had lost a lot of weight, and was suffering from starvation disease (Kowalczykowa; Münch; Höss).

Before he was deported to the concentration camp, W.J. was healthy, as evidenced by his 1939 medical examination, which was conducted when he applied for admission to a Polish air force college. He was not deliberately infected with TB. He had been through active tuberculosis, as evidenced by the positive sputum test, his high ESR reading and other symptoms, as well as the changes observed in his lungs on his chest X rays done in 1941 and now (Waitz). Presumably the operation was carried out fairly well from the technical point of view, in compliance with the fundamental principles of aseptic therapy. The operation’s outcome has to be considered favourable. Since that time tuberculosis has not been observed in the patient’s sputum, while the medical examination and tests carried out in our Zakopane clinic have shown a degree of respiratory failure commensurate with the degree of thoracoplasty.

***

Translated from original article: A. Metera and Rzepecki, W.M. “Torakoplastyka w Dachau.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1971.

Notes

- Klinika Chirurgii Klatki Piersiowej Studium Doskonalenia Lekarzy w Zakopanem.a

- The article was first published in 1971 and describes the state of medical knowledge at the time of its publication.b

- On the basis of this information and using the list of prisoners sent to Auschwitz from Tarnów jail on 14 June 1940, W. J. May be identified as Jan Walczak. Cf. http://www.chsro.pl/pierwszy-transport/lista.html.a

- Probably Karl Fritzsch, Höß’s deputy. Fritzsch managed the everyday affairs of the camp, and his official title was Schutzhaftlagerführer. He was appointed to this post on 14 June 1940, the day the first transport of Polish prisoners arrived. See http://www.deathcamps.org/occupation/auschwitzmen.html.a

- For pseudo-medical experiments conducted in Dachau concentration camp, see https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/dachau.a

- Evipan (hexobarbitone)—a barbiturate produced by the Bayer pharmaceutical company and used as an anaesthetic. Cf. Clara Cotaru, “Evipan: The dark side of anaesthesia,” https://www.geoffreykayemuseum.org.au/evipan-the-dark-side-of-anaesthesia.a

- Dr Helmut Müllmerstadt (1913-1991) was an SS physician and conducted surgery on tuberculosis patients in Dachau. There has been controversy whether or not his activities in Dachau and Sachsenhausen concentration camps were criminal pseudo-medical experiments. See Paul Weindling, Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014, p. 62. See also Marco Pukrop, SS-Mediziner zwischen Lagerdienst und Fronteinsatz. Die personelle Besetzung der Medizinischen Abteilung im Konzentrationslager Sachsenhausen 1936–1945. PhD Dissertation, 2015, pp. 520-536. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/268939315.pdf. See also Anna von Villiez, “Nur eine Handvoll Täter? Unmoralische Menschenversuche im Nazionalsozialismus,” https://www.medizinundgewissen.de/fileadmin/websiteFiles/pdf/Nur_eine_Handvoll_Taeter.pdf. After the war an investigation was conducted against him by the West German authorities, but he never stood trial. Cf. https://www2.landesarchiv-bw.de/ofs21/suche/ergebnis1.php.a

- See Weindling, 62.a

- II Klinika Corób Wewnętrznych Akademii Medycznej w Warszawie.a

- White blood cells.a

- Red blood cells.a

- See on this website: S. Kłodziński, “Zbrodnicze eksperymenty z zakresu gruźlicy dokonywane w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych w czasie II wojny światowej” (1962), English version: “Criminal tuberculosis experiments conducted in Nazi German concentration camps during the Second World War” and “Zbrodnicze doświadczenia z zakresu gruźlicy w Neuengamme. Działalność Kurta Heissmeyera” (1969). English version forthcoming.a

- For the Dachau low-pressure experiments, see Comment 4.a

- Dr Rudolf Brachtel (1908–1988; in this article his surname is misspelled). In 1947–48 Brachtel was tried by an American court on charges of violation of the laws and usages of war and acquitted. Cf. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Brachtel and https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/dachau-war-crimes-trials.a

- A euthanasia centre operated in Hartheim Castle, Upper Austria under the Hitler regime. 30 thousand victims (including one thousand Polish citizens) were murdered there. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hartheim_Euthanasia_Centre and https://www.polska1918-89.pl/pdf/hartheim---zamek-smierci,2052.pdf.a

- Dr Johannes Lange is mentioned with Müllmerstadt and other SS physicians who performed surgeries on prisoners in Dachau. Next to the note there is a photo of their operating theatre. See http://www.majdanek.com.pl/eksperymenty/dachau.html.a

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—Website Editor’s note.

References

- Fejkiel, Władysław. 1961. “O służbie zdrowia w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu I (obóz główny). Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 44–51.

- Kłodziński, Stanisław. 1962. “Zbrodnicze eksperymenty z zakresu gruźlicy dokonywane w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych w czasie II wojny światowej.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 77–81. English version online on this website, “Criminal tuberculosis experiments conducted in Nazi German concentration camps during the Second World War”.

- Kowalczykowa, Janina. 1961. “Choroba głodowa w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 58–60. English version online on this website, “Hunger disease in Auschwitz,” translated by Władysław Chłopicki, https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/215170,hunger-disease-in-auschwitz.

- Mączka, Zofia. 1946. “Operacje doświadczalne przeprowadzane w obozie koncentracyjnym w Ravensbrück.” Polski Tygodnik Lekarski. 34/35: 1074–1079.

- Mitscherlich, Alexander, and Mielke, Fred. 1963. Nieludzka medycyna, Warszawa: Państwowy Zakład Wydawnictw Lekarskich. Polish translation of Medizin ohne Menschlichkeit (first German edition, Heidelberg: Lambert Schneider, 1947; English translation, Doctors of Infamy: The Story of the Nazi Medical Crimes, New York: Henry Schuman, 1949).

- Musioł, Teodor. 1968. Dachau 1933–1945. Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Śląskie.

- Münch, Hans. 1967. “Głód i czas przeżycia w obozie oświęcimskim.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 79–88. Hans Münch (1911–2001), German physician and bacteriologist, member of the SS staff of Auschwitz working at the Hygiene-Institut der Waffen-SS at Raisko, about 4 km away from the main camp of Auschwitz. Unlike his colleagues, Münch refused to participate in criminal experiments, and was the only accused to be acquitted in a trial of Auschwitz staff members before the Polish Supreme National Tribunal. See testimony of several witnesses in Chronicles of Terror, online at zapisyterroru.pl.

- Olbrycht, Jan. 1962. “Sprawy zdrowotne w obozie koncentracyjnym w Oświęcimiu.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 37–49.

- Paczuła, Tadeusz. 1962. “Organizacja I administracja szpitala obozowego KL-Auschwitz I.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 61–68.

- Półtawska, Wanda. 1963. “Operacje doświadczalne w obozie koncentracyjnym w Ravensbrück.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 90–97. English version online on this website, “Experimental operations at Ravensbrück concentration camp,” translated by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/193985,experimental-operations-at-ravensbruck-concentration-camp.

- Talewski, Roman. 1951. “Krótki zarys rozwoju chirurgicznego leczenia gruźlicy płuc z zaznaczeniem rozwoju tej dziedziny w Polsce,” Polski Przegląd Chirurgiczny. 5: 566–578.

- Waitz, Robert. 1961. “La pathologie des déporteés.” La Semaine des Hôpitaux. 37(33): 1977–1964. See the Polish version on this website and its English translation, “Investigation of the aftereffects of female survivors’ imprisonment,” translated from the Polish version by Maria Kantor: https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/236201,aftereffects-of-female-survivors-imprisonment.

- Wolny, Jan. 1966. “Wspomnienia sanitariusza z obozów w Dachau, Oświęcimiu I Mauthausen.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 198–202.

- Höss, Rudolf. 1960. Wspomnienia Rudolfa Hoessa, komendanta obozu oświęcimskiego. Polish translation from the original German by Jan Sehn and Eugenia Kocwa. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Prawnicze. For the English version of the autobiography of Rudolf Höss, seeCommandant of Auschwitz: The Autobiography of Rudolf Höss, Translated and edited by Constantine Fitzgibbon et al. Phoenix: 2000.

- Zielina, Jan. 1964. “Blok 9 szpitala obozu Oświęcim I.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Pp. 82–84.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.