Author

Stanisław Sterkowicz, MD, PhD, 1921–2012, internal medicine, public health, and cardiology specialist, Neuengamme survivor (prisoner No. 78536), soldier of the Home Army, author of books examining the crimes committed by Nazi German physicians during the Second World War.

Neuengamme was set up as a concentration camp in June 1940, when the Arbeitslager sub-camp of Sachsenhausen on the site was upgraded to the status of an independent entity. Neuengamme is situated about 20 km south-east of Hamburg,1 and had 58 sub-camps with a catchment area covering the north-western part of Germany. In the five years of its existence, Neuengamme held over 106 thousand prisoners (87.5 thousand men and 13.5 thousand women) from 28 countries (Kampfert). Over half of that number—about 55 thousand—lost their lives in this camp. The high death rate was due to the inhuman way prisoners were treated, the poor quality of their food, their exhaustion by an excessive amount of work, the fact that weaker prisoners were killed, and other concentration camp realities. One of the most tragic incidents in the history of the Nazi German concentration camps occurred in connection with Neuengamme in the last days of the War.2 Its prisoners were evacuated and put on board the Cap Arcona, Thielbeck, and Athenin the Bay of Lübeck. These ships were accidentally bombed and sunk by the Royal Air Force. Only 2,400 of the 9,400 on board survived.

Quasi-scientific medical experiments were conducted in Neuengamme, just as in other concentration camps (Jakubik and Ryn, 71), but on a much smaller scale and range of different types of procedures than in other camps. Most of these experiments were carried out by physicians who were not members of the staff of Neuengamme.

Typhus experiments

In late 1941 an epidemic of typhus broke out in Neuengamme. The I.G. Farben3 production plant situated in Höchst-am-Main sent in a pharmacological substance which was tested on a group of prisoners who contracted the disease. The tests started in late January, when the biggest wave of the epidemic was over. The German doctors who managed the tests have not been identified so far.4 The physicians on the camp’s staff were so afraid of catching the disease that they did not see prisoners at all, and the observations on patients and collection and dispatch of test samples were handled by the male nurses.

The I.G. Farben Industrie Company sent consignments of the drug packed in cardboard boxes to SS Unterscharführer Willy Bahr5 in the camp, who passed them on to the camp physicians (Wackernagel). The transportation of the drug to the prisoners’ hospital was handled by Kapo Mathias May6 and male nurse Günther Wackernagel.7 The tablets were put in a wooden crate about 50 x 25 x 25 cm in size (20 x 10 x 10 inches), with the original cardboard box marked “I.G. Farben” inside. Instead of the regular type of inscription giving the name of the tablets and their producer, there was just a typewritten number on the box. A leaflet was attached with instructions how to apply them. The leaflet also said what samples were to be collected from the patients and sent in for bacteriological tests.

Willy Bahr selected prisoners for the tests from the group of typhus patients. About a hundred patients are estimated to have been “treated” with these unidentified substances. The treatment lasted for a fairly long time (Wackernagel).

Urine and stool samples were taken from patients, put into small containers marked with the number of the tablets,and packed in a special crate which was sent out to the hospital entrance every day or every two days. SS men collected it and dispatched the samples to one of the SS institutes for bacteriological tests. The results were to be used to assess the “treatment.”

Wackernagel believes the samples were sent to the Hamburg Institute of Tropical Medicine,8 or perhaps to one of the I.G. Farben labs. There was a close connection between the SS Institute of Hygiene9 and the Hamburg Institute of Tropical Medicine,which supplied anti-typhus vaccine for the SS.

The test results for the treatment of typhus using unidentified pharmacological substances were negative. No improvement was observed in the condition of patients who were forced to take these drugs. But neither were there any bad effects. So the only harm done was the withdrawal of proper treatment in order to obtain information on a new, tentative therapeutic method. This type of withdrawal of treatment was generally practised on sick prisoners, while preventive measures in the form of vaccination and treatment using serum were strictly reserved for the SS.

It was believed that the tested substance was one of the sulphonamides. Ex-nurse Wackernagel recalls that the medications available in the prisoners’ hospital at the time included Uliron, Prontosil, Albucid, Neouliron, Eubasin, and Eleudron.10 But it was known that these drugs were of no use for the treatment of typhus. The drug that was tested has not been identified.

Drinking water decontamination trials

These tests started in early 1945 (Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial Transcripts). The project was strictly confidential and it was carried out in absolute secrecy, so prisoners failed to notice it. It is not mentioned at all in the work published on the concentration camps. The need for tests of this kind was discussed at a special meeting called by Karl Brandt,11 Reich Commissioner for Health and Sanitation, held on 4 December 1944. At this meeting Dr [Wolfgang] Wirth,12 a senior staff officer, put forward a proposal for tests to detoxify drinking water contaminated with the derivatives of mustard gas (Yperite).13 Test of this kind had been conducted before, and the new ones were only intended to verify their results in a set of practical trials to test the organoleptic properties of decontaminated water.

Undoubtedly, in wartime there was a need to undertake defensive measures against the risk of chemical weapons which the enemy could have used to destroy human life and resources. So these tests would have been perfectly justified if they had been risk-free to the human body and carried out with the informed consent of the persons who were subjected to them. However, the pseudo-scientific experiments conducted in the Nazi German concentration camps never observed such conditions.

A recommendation to have these tests carried out was submitted to the Reich Office for Water and Air Resources (Reichsanstalt für Wasser- und Luftgüte).14 Dr Jäger, an expert working for this institution, and Kumpfert, one of its inspectors, apparently obtained Himmler’s permission15 to conduct the tests on 150 inmates from a more less homogeneous group.

The constructor Haase16 of the Reich Office for Water and Air Resources designed a device for the decontamination of drinking water. The device needed to be tested out for its practical applicability. Its implementation and operation was to be supervised by the camp physicians of Neuengamme in the presence of Dr Ebel of the Reich Office for Water and Air Resources. Water which had been contaminated was supposed to be potable on being passed through the device. So the aim of the project was to see whether this claim held good by testing it out on human subjects.

The first stage was to see whether the use of a solution of ferrous sulphate as a decontaminating agent had any negative effects on prisoners’ health. In the next stage of the tests a decontaminating agent was added to the water which had contaminated with a chemical weapon containing arsenic using Lewisite in liquid17 form and a solid substance code-named “Dora.” A derivative of mustard gas was used in a third series of tests. The experimenters wrote in their report that no bad effects were observed on the health of the prisoners.

These experiments were discussed during the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial. Karl Brandt mentioned them in his statement (Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial Transcripts; seeU.S.A. v. Karl Brandt et al.: The Doctors’ Trial Summary). Counsel for the defence argued that strictly speaking, they were not medical tests, since the chemical tests were carried out with decontaminated water in which the presence of harmful substances was not observed, and the aim of the experiments was to determine the organoleptic properties of the decontaminated water. In reality the tests were a practical trial run of the apparatus which had operated well in laboratory conditions, but might have failed in a practical application on a mass scale. For the sake of safety, the test were conducted on concentration camp prisoners to avoid putting German citizens at a potential risk of being poisoned should the apparatus prove defective.

A total of 150 prisoners were subjected to the tests (Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial Records; statement of Karl Brandt). We may speculate that the test turned out to be harmless for the prisoners, as evidenced by the fact that fellow-inmates did not notice it. The subsequent developments of the War showed that there was no need for these tests, though of course the team that organised them could not have foreseen that.

Photo 1. Archival photograph of Neuengamme concentration camp. The insert shows the camp’s SS staff. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1977..

Surgical training

Just like their colleagues in many other concentration camps, the SS physicians in Neuengamme performed a variety of surgeries with no specific indications but simply because they fancied doing a particular operation. Neither the type and number of these operations, nor the names of the victims and experimenters have been established. There are a couple of records of such operations in the recollections of Neuengamme survivors.

Bogdan Suchowiak writes that Mathias May, the kapo of the prisoners’ hospital, performed leg amputations. Karl Kampfert writes that some doctors, for instance Jäger, conducted private experiments on prisoners without official permission. Jäger was a graduate of dentistry, but his ambition was to practise surgery. One day he amputated a prisoner’s injured arm, using no anaesthetic and with the prisoner fully conscious (Kampfert).

Phlegmon experiments

A fairly small scale of experimentation was carried out in Neuengamme to test the effectiveness of sulphonamides for the treatment of phlegmons and diarrhoea. The nature of these experiments was not criminal.

The phlegmon experiments conducted in the prisoners’ hospital at Neuengamme started in 1943. Unlike the Sachsenhausen and Dachau experiments for the treatment of phlegmons, in Neuengamme they were carried out on prisoners who were genuinely ill, not artificially infected. The prisoners subjected to the tests were divided into four groups, as I have learned from a statement by Franciszek Czekała,18 a male nurse in the camp. The first group were treated with Eubasin; the second group received Eleudron; the patients in the third group had their abscesses cut and were then treated with Marfanil,19 a powdered sulphonamide. The fourth was a control group, and the treatment prisoners in this group got consisted of baths in a solution of potassium permanganate. The tests were conducted by the camp physicians. A total of about a hundred prisoners were tested. There was certainly a need to find the best method to treat wound infections, and that was the reason for the tests. Reports with the results must certainly have been drawn up and sent to the relevant authorities as well as to the pharmaceutical companies that supplied samples for the tests. Many medical institutions employ a similar procedure, as we know.

Dr Jäger conducted sulphonamide experiments of a different type. At the time he was conducting a research project for his doctor’s degree, and decided to examine the effect of sulphonamides for the treatment of diarrhoea (Suchowiak). The Bayer Company supplied him with a consignment of sulphonamides for the tests. Jäger selected subjects for tests from the large number of prisoners coming to the hospital for treatment. He was assisted by Maurycy Mittelstädt,20 a Polish prisoner-doctor, who made use of Jäger’s I.G. Farben contacts to obtain large quantities of sulphonamides, purportedly for the diarrhoea tests, but secretly distributed them to prisoners. These experiments could hardly be called criminal. In view of the reaction mechanism of sulphonamides on the bacterial flora of the digestive system, the effects of these substances could well have been very beneficial for prisoners. Moreover, we cannot deny that the experiment brought additional benefits for the prisoners who participated in it—they could stay in the hospital for a fairly long period for observation.

The sulphonamide tests carried out in Neuengamme were beneficial, and as such are an exception to the general rule of the harmfulness of the diverse medical experiments performed in the Nazi German concentration camps, showing that it was possible to conduct medical experiments in a humanitarian way without doing harm to prisoners or patients.

Tuberculosis experiments

The tuberculosis experiments conducted in Neuengamme were definitely one of the most ruthless and pointless research programmes German SS doctors carried out in the concentration camps. There was no sensible reason to carry them out. They were performed not only on adult prisoners, but on children as well. Most of the victims who survived these experiments were later killed. This included the children who served as guinea-pigs: as the War was coming to an end,21 they were hanged like notorious criminals in the basement of the Bullenhuser Damm School in Hamburg.

The scheme was launched and carried out by the physician Dr Kurt Heissmeyer, who specialised in the treatment of lung diseases and was head of the TB ward in the SS and police sanatorium at Hohenlychen.22 Heissmeyer came from a family of physicians and was brought up to be a good Nazi. After graduating he specialized in the treatment of lung diseases and in 1938 was appointed head of the TB ward in Hohenlychen, which had had an SS management since 1942. Working in Hohenlychen side by side with the surgeon Prof. Karl Gebhardt, who was the SS chief clinician, gave Heissmeyer the opportunity to meet the top figures in the SS medical service. A few words need to be said here about Heissmeyer’s criminal activities, the special feature which marked him out and without which the picture of the Neuengamme experiments would be incomplete.

Kurt Heissmeyer was a fanatical Nazi, and grafted the Nazi ideology onto the substrate of his clinical specialisation. The papers he published in medical journals were on the social aspects of tuberculosis, as seen from the racist point of view, for instance a paper on the basic duties in post-therapeutic social welfare for the German TB prevention programme; and another paper in the same year and journal on the treatment of TB patients and those with other diseases at the Hohenlychen sanatorium.23 In another of his papers Heissmeyer wrote the following:

It cannot be denied that the present time is under the all-embracing influence of a new worldview. The foundation of this worldview is grounded in the concept of “The People and the Race,” which is an idea that entails a reappraisal of the concept of “the human being” and hence forces the physician to adopt this point of view in the treatment of individual patients. When it comes to the selection of patients for therapy in health institutions, preference must be given to those who are the best for the preservation of “The People and the Race,” even if their current condition is less promising than that of others who are racially inferior. In future only patients who meet the racial criterion should be given the opportunity to receive treatment for an indefinite period of time, while the racially inferior should be treated only for a limited length of time for the sake of scientific progress.24

Heissmeyer, “Grundsätzlichesüber Gegenwarts- und Zukunftsaufgaben der Lungenheilstätte.”25

Heissmeyer’s professional status backed up by his pseudo-scientific racist publications helped him accomplish his ambition to obtain the habilitation degree.26 To do this, he had to present a dissertation based on a practical research project. He was fascinated by the ideas of the Austrian lung specialist Kutschera-Aichbergen,27 who claimed that TB patients could be treated by giving them a secondary infection of cutaneous tuberculosis, which would enhance their immunity. Heissmeyer wanted to check this up and examine the role of immunisation in pulmonary tuberculosis.

By the time Heissmeyer was planning his research project, Kutschera-Aichbergen’s hypothesis had already been evaluated from the clinical point of view and rejected as useless and dangerous for patients. A lung specialist with Heissmeyer’s professional experience must have been well aware of the criticism, but that did not stop him from proceeding with his experiments, especially as he was going to conduct them on concentration camp prisoners, in other words, on people Nazi ideology said need not be taken into account at all.

Heissmeyer’s research was to find answers to the following questions:

- Could frequent intracutaneous injections of live TB bacteria administered to fully healthy persons infect them with pulmonary tuberculosis?

- Could this procedure bring about tuberculosis in persons not suffering from active pulmonary tuberculosis but with a positive result for the Moro tuberculin test?

- How would pulmonary tuberculosis develop in persons suffering from its bilateral advanced cavitary form if they were recurrently infected with bacteria from their own inflammatory foci?

- Could the recurrent intracutaneous injection of TB bacteria of patients with unilateral pulmonary tuberculosis bring about an infection of the healthy lung if TB bacteria were brought into it with the use of a probe?

- Was there a difference between the development of pulmonary tuberculosis due to artificial infection in adults and children, and in patients who had already been through TB and persons with a negative tuberculin reaction?

As Heissmeyer continued his experiments in Neuengamme concentration camp, he expanded his agenda, for example he started to conduct post mortems on the bodies of victims killed after he finished a particular phase of his experiments. Scientifically, all of his work was worthless, as the committee of experts confirmed during his trial after the War.

To accomplish such an extensive research programme, Heissmeyer had to have vast resources of patients at his disposal. Obviously, nowhere else except in a concentration camp would he have had the opportunity to carry out his experiments on children. His good relations with the top brass of the SS—Oswald Pohl,28 Karl Gebhardt, and Ernst Grawitz29—whom he often saw in Hohenlychen, helped him put his plan into practice. He could count on his powerful mentors to help him obtain the consent he needed to perform his experiments on concentration camp prisoners. Gebhardt and Grawitz wrote recommendations for the project. Pohl was head of the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, Reich Main Security Office), and could give the projectpriority status.

In the spring of 1944 Dr Heissmeyer met with Dr Conti,30 Prof. Grawitz, and Prof. Gebhardt in the officers’ mess at Hohenlychen. They promised to assist him with his research and enable him to carry it out on concentration camp prisoners. This fact is mentioned in the grounds for the verdict handed down by the Magdeburg criminal court31 in Heissmeyer’s trial (I have a photocopy of this document, which is dated 30 June 1966). As Hohenlychen was just 14 km away from Ravensbrück, Heissmeyer tried to make arrangements to carry out his research in that concentration camp. However, Pohl did not issue approval for the scheme, because information on experimental operations done on women prisoners in Ravensbrück would have been likely to reach the outside world and spread abroad, earning general censure. That was why he designated a concentration camp that was further away, Neuengamme near Hamburg, for Heissmeyer’s experiments. Nonetheless, he promised to help with the supply of a sufficient number of prisoners needed for the experiments.

Having acquired such wide-ranging powers of attorney, in late April 1944 Heissmeyer arrived in Neuengamme in the company of Enno Lolling,32 chief physician for all the concentration camps. The Neuengamme commandant’s office had received advance notice and had been ordered to get the facilities ready for Heissmeyer’s experiments. He was allocated part of Block 4, which was screened off from the rest of the barrack with wire and a wooden fence. Dr Tadeusz Kowalski,33 and Dr Szafrański34 were chosen from the group of Polish prisoner-doctors in the camp and sent in to look after Heissmeyer’s guinea-pigs. Later on two French prisoner-doctors, Dr Gabriel Florence35 and Dr René Quenouile,36 were sent in to replace them. There were also two Dutch prisoners who were male nurses, Deutekom and Hölzel,37 who were to provide nursing care for the guinea-pigs.

The first experiments on the prisoners started in June 1944. The last experiments involving children took place in March 1945. The prisoners selected for the first run of tests were Poles and Russians. They were selected either by Heissmeyer himself, or in accordance with his instructions for the conditions the victims had to meet. Three groups of prisoners were selected for the first run of tests, a group with bilateral TB, a group with unilateral TB, and an extra-pulmonary TB group.Subsequent tests were performed on healthy prisoners as well.

The tests started with the application of active, virulent TB sent in from Prof. Meinicke’s38 bacteriological laboratory in Berlin. The prisoners selected for the test had a live strain of TB bacteria injected into the area of the heart muscle, which caused general, bilateral, and local reactions, as reported by Dr Tadeusz Kowalski in his lecture delivered to the local medical society at Kowary in 1946. A week after the injections, each of the guinea-pig prisoners had one of his lymph glands removed near the place where he had had the injection. These samples were sent to Berlin, where new TB cultures were grown from them. The suspensions obtained were sent back to Neuengamme, and each of the guinea-pigs was injected with a dose derived from the lymph glad that had been removed from him. Injections were repeated at intervals of a fortnight. In addition, each guinea-pig had his own spittle rubbed into his scar.

Using a probe, Heissmeyer introduced TB bacteria into the healthy lung of at least 16 adult prisoners, some of whom had never had pulmonary tuberculosis. These experiments were usually done on prisoners who had been sentenced to death, which was particularly convenient for Heissmeyer, because when the experiments were over, the victims were killed and Heissmeyer took part in the post-mortems to collect histopathological data.

In the autumn of 1944 Heissmeyer wanted to start TB experiments on children. Through the services of his mentors Gebhardt and Pohl, 20 Jewish children aged 4 to 12 were brought in for Heissmeyer from Auschwitz. These Jewish children came from various European countries, most of them from Poland. Heissmeyer continued to perform his ruthless experiments on children until March 1945. After three months of the experiments, most of the children had developed tuberculous changes in the mediastinal lymph nodes. After four months infiltrates started to develop, and by April 1945 tuberculous cavities could be observed.

On the basis of the records, it has been established that in the nine months for which Dr Kurt Heissmeyer conducted his activities in Neuengamme (commuting from Hohenlychen), he experimented on about a hundred adults and twenty children. Not many of his guinea-pigs survived these experiments. Even if any of them did manage to get through to the end of these criminal experiments, they were killed afterwards by Nazi German henchmen. That was the fate of all the children subjected to these experiments.

In the latter half of April 1945, when it was clear to all Germans that nothing could save Nazi Germany, the experimenters hastily set about getting rid of the evidence of their ruthless experiments. Heissmeyer took away the records ofhis experiments and hid them in a special crate which he ordered his staff to bury in the grounds of Hohenlychen. Meanwhile, SS Obersturmbannführer Max Pauly,39 the commandant of Neuengamme, received a telephone call from his superiors in Berlin with orders to kill the children who had witnessed Heissmeyer’s “scientific activities” and were still alive.

The order was carried out on the night of 20/21 April 1945. All the children, their carers the Dutch nurses and the French prisoner-doctors, were taken to a sub-camp of Neuengamme located in a school building on Bullenhuser Damm in Hamburg. The children were attended by the concentration camp physician Dr Albert Trzebinski,40 who was responsible for supervising the execution. The order to have the children hanged was given by SS Hauptsturmführer Arnold Strippel41 (Trzebinski’s testimony in the Curiohaus Trial).

The children were brought down to the air raid shelter in the basement of the school. They were told to undress, and Dr Trzebinski gave each of them an injection of morphine to make them fall asleep or unconscious. Next, SS Unterscharführer Johann Frahm42 hanged the children from hooks attached to the central heating pipes. At the same time Deutekom and Hölzel, the children’s two Dutch carers, and the Frenchmen, the biologist Prof. Florence, and the radiologist Dr René Quenouilel, were hanged in another room in the basement.

Heissmeyer’s experiments showed that the lymphatic system set up a barrier which for a certain time prevented the TB bacteria from reaching the lungs, and that healthy lungs did not have an inherent immunity of their own. These were widely known facts in the medical community and did not require further confirmation, certainly not on prisoners without their informed consent and at great risk to their lives. So Heissmeyer’s research has to be considered scientifically pointless and redundant, as well as performed at the expense of the suffering and death of many persons.

Professors Prokop, Steinbruck, Schubert, and Landmann, the team that issued an expert opinion for the court in the proceedings against Heissmeyer, observed that his experiments were pointless from the very outset. He must have known from the medical literature available at the time that TB could not be cured using his method. Moreover, he must have realised that a secondary infection of TB, which he induced artificially, was particularly dangerous, especially for children, who are at high risk of infection if exposed to TB. Heissmeyer’s pseudo-scientific fanaticism encouraged him to conduct ruthless and criminal experiments on children, despite the fact that he was well aware of the imminent defeat and fall of Nazi Germany.

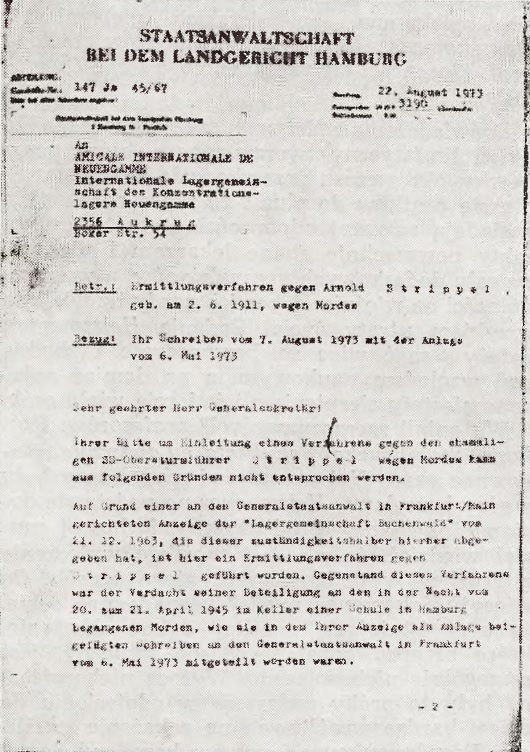

Photo 2. The Hamburg prosecutor’s letter notifying the Secretary-General of the association of Neuengamme survivors Amicale Interationale de Neuengammethat its complaint against the acquittal of SS Obersturmführer Arnold Strippel has been dismissed (22 August 1973). Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1977.

After the War the trial of the staff of Neuengamme was held in Hamburg from 18 March to 3 May 1946. Heissmeyer’s experiments were discussed, but their chief perpetrator was not in court. He had gone into hiding in Holland. The defendants included the accomplices to the ruthless murder of the child victims of Heissmeyer’s experiments—SS physician Alfred Trzebinski, who sedated the children; SS Unterscharführer Willi Dreimann, the Rapportführer of Neuengamme who was in charge of transportation; SS Unterscharführer Johann Frahm, who hanged them; Ewald Jauch, the commandant of the sub-camp in Bullenhuser Damm school; SS Hauptsturmführer Karl Wiedemann, the commandant of all the sub-camps in Hamburg; and SS Oberscharführer Adolf Speck, who brought the children to the camp. All these defendants, except for Wiedemann, were sentenced to death. Wiedemann got a prison sentence of 15 years (Trzebinski).

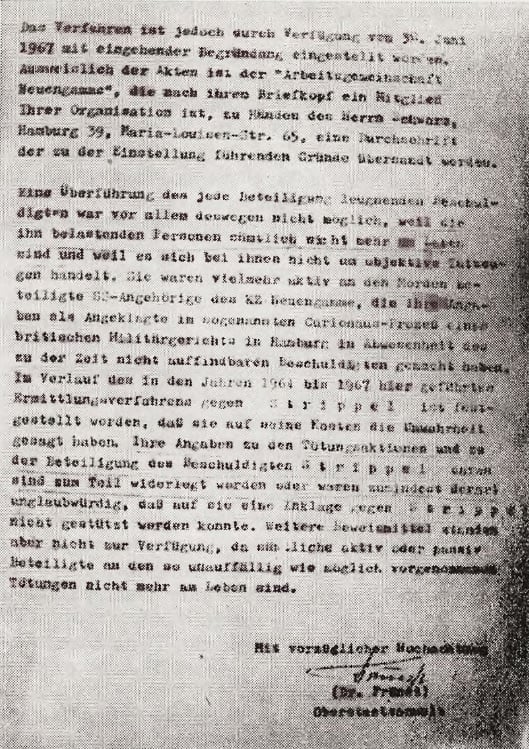

SS Hauptsturmführer Arnold Strippel, who had ordered Jauch and Frahm to hang the children and their four carers, was not in court, either. He had gone into hiding in Schleswig-Holstein and was working as a farmhand under a false name. He wasn’t apprehended until 1948. Strippel had a prolific CV as one of the henchmen of Buchenwald, and in 1949 he was convicted for his activities in that camp and sentenced to life imprisonment. However, he was released in 1969 and the charges against him were reviewed. The sentence against him was declared a miscarriage of justice and he was charged in new proceedings merely with aiding and abetting in the murder of prisoners, for which he got a sentence of six years in prison (VVN-Bund der Antifaschistischen). But as he had already spent 21 years in jail, he was paid out compensation amounting to 150 thousand DM. He never stood trial for his part in the Bullenhuser Damm atrocity. A group of survivors of Buchenwald and Neuengamme lodged a complaint to the West German prosecution service, but it was dismissed.

Photo 3. Last page of the Hamburg prosecutor’s letter concerning Arnold Strippel to the Secretary-General of Amicale Internationale de Neuengamme. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1977.

SS Unterscharführer Willi Bahr, another of Heissmeyer’s accomplices in the Neuengamme experiments, was also a defendant sentenced to death in the Curiohaus Trial.

It wasn’t until December 1963 that the long arm of the law caught up with Kurt Heissmeyer. For many years the perpetrator of the ruthless Neuengamme experiments had been practising as a physician specialising in lung diseases in Magdeburg in the German Democratic Republic. In the autumn of 1963 he was recognised by a survivor of Neuengamme. An investigation was conducted against him, followed by a trial. On 30 June 1966 the Magdeburg court sentenced Heissmeyer to life imprisonment. A year later he died in prison.

***

Translated from original article: S. Sterkowicz, “Pseudomedyczne eksperymenty w obozie w Neuengamme.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1977.

Notes

The author gives the numbers of persons embarked on the Cap Arcona and Thielbeck ships and a number of those who sunk already in the opening part of the article. Historians nowadays treat estimating the victims of the sinking of the aforementioned ships with great caution, and the Sterkowicz’s numbers are considered to be tantamount to taking a stance on the circumstances of the disaster in question. Sterkowicz does not cite the source of his information.

- Currently the Neuengamme site lies within the Hamburg municipal area. For the history of the Neuengamme camp, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuengamme_concentration_camp and https://www.kz-gedenkstaette-neuengamme.de.

- These ships, along with a fourth, the Deutschland, were accidentally bombed and sunk by the Royal Air Force in the belief that fleeing Nazis were on board. https://theconversation.com/why-the-raf-destroyed-a-ship-with-4-500-concentration-camp-prisoners-on-board-75903.

- I.G. Farben was a conglomerate of eight leading German chemical manufacturers, including Bayer, Hoechst and BASF, which at the time were the largest chemical firms in existence. This industrial potentate provided the technology Nazi Germany needed to implement its policies, including the establishment and running of the concentration camps. Höchst is now part of Frankfurt-am-Main. See http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/economics/igfarben.html.

- According to the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the typhus experiments were carried out by scientists from the Institute for Marine and Tropical Diseases (Institut für Schiffs- und Tropenkrankheiten). https://en cyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/neuengamme

- SS Unterscharführer Wilhelm Bahr (1907–1947) Nazi German war criminal, Neuengamme staff member. Apprehended after the War and brought to justice as one of the defendants in the Curiohaus Trial, convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged. Klee, Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. . ., 25.

- Mathias May’s 1946 statement is quoted in Konflikte um das Verhalten . . ., 13–14. http://media.offenes-archiv.de/ha4_2_3_thm_2425.pdf. Another favourable report on Mathias May is in Megargee, Geoffrey P., ed. “Neuengamme Main Camp.” The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, Vol. I, 1073–1078. “In the main camp, the infirmary Kapo, Mathias May, would step in to protect prisoners from seizure by the SS.” (p. 1077).

- Günther Wackernagel (1913–2001). Pre-war member of the KPD (Communist Party of Germany), imprisoned under the Nazi regime and held in various concentration camps, including Neuengamme. Sent to the eastern front, and when taken prisoner by the Soviets in 1945 volunteered to join the Red Army. On release lived in East Germany, working in the police force. Activist of the Committee of Anti-Fascist Resistance Veterans of the German Democratic Republic; wrote an autobiography, Zehn Jahren gefangen, East Berlin: Verlag Neues Leben, 1987. http://media.offenes-archiv.de/HA2_1_3_bio_1606.pdf.

- The Institute for Marine and Tropical Diseases; now the Bernhard-Nocht-Institut für Tropenmedizin; see Comment 5.

- Presumably both institutions were located in Hamburg, though it is not quite clear which SS Institute of Hygiene is meant. The Germans wanted the Hamburg Institute for Marine and Tropical Diseases to be a model for similar institutions in occupied countries and reorganised its Warsaw counterpart along these lines. See Marta Gromulska,“Państwowy Zakład Higieny w czasie wojny w latach 1939–1944,” Przegląd Epidemiologiczny / Epidemiological Review. 2008, 62(4): 719–725. Available online under the link.

- Uliron—sulphonamide drug for the treatment of pemphigus, manufactured by Bayer. Prontosil—sulphonamide drug manufactured by Bayer for the treatment of fungal skin infections. Albucid (eye drops), Neo-uliron, Eubasin, and Eleudron were other sulphonamides produced by Bayer for the treatment of diverse conditions. Rudolf Franck, Moderne Therapie in innerer Medizin und Allgemeinpraxis. Handbuch . . .. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1941 (12th edition).

- Karl Brandt (1904–1948), head of the Nazi German health and sanitary service, “Hitler’s doctor,” the highest-ranking defendant in the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial, found guilty on 3 charges, sentenced to death and hanged. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Brandt_(Mediziner).

- Wolfgang Wirth (1898–1996), head of the Institute for Pharmacology and Military Toxicology of the Military Medical Academy; participant (witness) in the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial. Klee, Deutsche Medizin im Dritten Reich, 299–303; Klee, Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. . ., 681. https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q2591794https://www.medvik.cz/link/xx0214065. Florian Schmaltz (2017: 246–253.

- Mustard gas (Yperite)—one of the first chemical weapons used during the First World War as a poison gas. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Mustard-gas.

- Schmalz, 246–253.

- Schmaltz (252–253) writes (on the basis of German records) that “on February 16, 1945, Himmler withdrew his approval [which he had issued in 1943] ‘in consideration of the current situation.’” Germany’s final defeat was unavoidable, but “the scientists still tried to make use of the last opportunity to exploit the lives of the concentration camp inmates at their disposal and ruthlessly subjected them to lethal human experiments.”

- Karl Ludwig Werner Haase (1903–1980), head of the Reich Office for Water and Air Resources, a graduate in chemistry. Schmaltz, 246–248ff.

- Schmalz (247–248) writes that tests with water contaminated with Lewisite, a chemical containing arsenic, preceded the tests with “nitrogen mustard gas.”

- Franciszek Czekala (b. 25 April 1911; note differently spelled surname) is on the list of Polish survivors of Neuengamme on the Lübeck–Neustadt transport. Cf. Zapisy terroru / Chronicles of Terror, online at https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/.

- An article on this German drug used to treat wounds appeared in 1944 in Nature. “Marfanil.” Nature. 1944. 153, 707. https://doi.org/10.1038/153707a0.

- Dr Maurycy Fryderyk Oswald Mittelstaedt (1902–1980), a Polish physician, after the War practised in internal medicine in Warsaw. http://www.barbarafamily.eu/webtrees/individual.php?pid=I9124&ged=2018.

- On the night of 20/21 April 1945. For more on the Bullenhuser Damm atrocity, see the website of the memorial, (under the link) and the article by Stanisław Kłodziński on this website, English version “Criminal tuberculosis experiments conducted in Nazi German concentration camps during the Second World War.” Also see other publications by Kłodziński in the references at the back of this article. For more on Dr Kurt Heissmeyer, see http://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss1_2_3_bio_1986.pdf (in German).

- Hohenlychen, situated about 75 km north of Berlin, was one of the main centres used by the SS and German police for medical treatment. Its staff included physicians who were war criminals, such as SS-Sturmbannführer Dr Karl Gebhardt, who was sentenced to death in the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial. Cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hohenlychen_Sanatorium; https://www.abandonedberlin.com/hohenlychen.

- These articles are available online at https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0028-1124178 and https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0028-1124156.

- Sterkowicz quotes the passage in the original German, followed by a Polish translation.

- This paper has also received a comment from Paul Weindling (p. 265).

- The habilitation is a post-doctoral degree some European universities (formerly especially the German universities) require from scholars who want to pursue an academic career.

- Hans Kutschera-Aichbergen (1890–1940). Austrian internist. Name misspelled in Sterkowicz’s article.

- SS Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl (1892–1951), chief administrator of the Nazi German concentration camps, a key figure in the design and implementation of the Final Solution. Arrested after the War and tried by the American Military Court on charges of war crimes. Convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pohl_trial.

- SS Obergruppenführer Ernst-Robert Grawitz (1899–1945). Reich Physician of the SS and Police, head of the German Red Cross. Involved in experiments on concentration camp inmates, especially in the children’s camp in Łódź. See Schafft, 159–163.

- SS Obergruppenführer Leonardo Conti (1900–1945). German physician, Reich Health Leader. Involved in T4, the Nazi involuntary euthanasia programme, and in pseudo-medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners. Imprisoned after the War but committed suicide before the Doctors’ Trial started. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonardo_Conti.

- I Strafsenat des Bezirksgerichts Magdeburg.

- SS Standartenführer Dr Enno Lolling (1888–1945). Chief physician at the Concentration Camps Inspectorate. Committed suicide at the end of the War. Lifton, 180. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enno_Lolling.

- Dr Tadeusz Kowalski. Polish prisoner-doctor held in Auschwitz-Birkenau and Neuengamme. Witnessed the Bullenhuser Damm atrocity and testified against its perpetrators in the Curiohaus Trial. Cf. http://media.offenes-archiv.de/Rathausausstellung_2017_Curio_10.pdf. Zdzisław J. Ryn, “Lekarze-więźniowie w Auschwitz-Birkenau,” 65.

- Dr Zygmunt Szafrański (1913–1975?), Polish physician, prisoner-doctor held in Neuengamme, 1941–1945; made an extensive statement in 1946 on Neuengamme to Polish investigative judge Kazimierz Borys. Cf. Zapisy terroru. Chronicles of Terror. Online at https://www.zapisyterroru.pl.

- Dr Gabriel Florence (1886–1945). French professor of biological and medical chemistry at the University of Lyon. Cf. http://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de/_english/prof_gabriel_florence.php.

- Dr René Quenouille (1884–1945). French radiologist. http://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de/_english/dr_rene_quenouille.php.

- Dirk Deutekom and Anton Hölzel (misspelled “Hölzl” in Sterkowicz’s text). http://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de/_english/antonie_hoelzel.php; http://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de/_english/dirk_deutekom.php.

- Ernst Meinicke (1887-1945). German physician. Name spelled “Meinecki” in Sterkowicz’s article. “In June 1944, Heissmeyer enthusiastically began his experiments at Neuengamme. He obtained a strain of live tubercle bacilli from a Berlin bacteriologist named Meinicke. Meinicke was unaware of Heissmeyer’s intentions, and warned him against testing the bacteria on people.” https://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=67121.

- SS Sturmbannführer Max Pauly (1907–1946). German war criminal. Commandant of Stutthof and Neuengamme concentration camps. Ordered the execution of the Polish defenders of the Danzig/Gdańsk post office. After the War stood trial before the British military court, convicted of war crimes, sentenced to death and hanged. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Pauly.

- SS Hauptsturmführer Alfred Trzebinski (1902-1946). Nazi war criminal active as a doctor in Neuengamme. After the War tried by a British military court, convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged.

- SS Hauptsturmführer Arnold Strippel (1911-1994). German war criminal and mass murderer. Served in various concentration camps. Apprehended in 1948 and convicted to life imprisonment. Released in 1969. Cf. http://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss1_2_2_bio_2117.pdf.

- Johann Frahm (1901–1946). Nazi German war criminal, deputy of Ewald Jauch, commandant of the Bullenhuser Damm sub-camp, 1943–1945. After the War apprehended, tried by the British Military Tribunal in the Curiohaus Trial, convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged.

General introductory note by Teresa Wontor-Cichy, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project. Numbered notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project, in cooperation with Maria Ciesielska, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

Archival materials and sources

I Strafsenat des Bezirksgerichts Magdeburg. Grounds issued by the Magdeburg court for the verdict in the criminal proceedings against Kurt Heissmeyer, 30 June 1966. Photocopy of the original German documentin the possession of Stanisław Sterkowicz.

Czekała, Franciszek. Statement made by Franciszek Czekała, former nurse in the prisoners’ hospital at Neuengamme concentration camp; a copy in the possession of Stanisław Sterkowicz.

Dr Kurt Heissmeyer, biography. http://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss1_2_3_bio_1986.pdf

Gedenkstätte Bullenhuser Damm. Website at https://bullenhuser-damm.gedenkstaetten-hamburg.de

Kampfert, Karl. Gutachten des Sachverständigen Prof. Dr Karl Kampfert gegen Kurt Heissmeyer [Statement made by Prof. Dr Karl Kampfert, expert witness in the proceedings against Kurt Heissmeyer; a copy in the possession of Stanisław Sterkowicz].

Konflikte um das Verhalten von Funktionshäftlingen und Auseinandersetzungen zwischen „Politischen“ und „Kriminellen“ im Hauptlager Neuengamme. http://media.offenes-archiv.de/ha4_2_3_thm_2425.pdf

Kowalski, Tadeusz. “O pasażach żywych prątków Kocha na organizmach dziecięcych w obozie koncentracyjnym Neuengamme w Niemczech” [On the passages of virulent TB bacteria in children’s bodies at Neuengamme concentration camp, Germany]; lecture delivered on 26 June 1946 at a meeting of a local medical society at Kowary and reported in themedical journal Śląska Gazeta Lekarska 1946, p. 712.

“Neuengamme Main Camp.” The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, Volume I: Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). 2009. Elie Wiesel et al. (eds.), Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16gzb17.37.

Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial Transcripts. “Chemical warfare (water) experiments.” For the online English version, see Harvard Law School Library Nuremberg Trials Project, http://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/search/?q=issue:%22Chemical+warfare+%28water%29+experiments%22. Sterkowicz cites the German-language version of the Nuremberg records, preserved in the Archives of the Polish Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi German Crimes Committed in Poland (GKBZHwP), Ref. No. ATW-1, Ldn-21, p. 2376 (now kept in the archives of the National Institute of Remembrance, Warsaw).

Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial Transcripts.U.S.A. v. Karl Brandt et al.: The Doctors’ Trial Summary. http://nuremberg.law.harvard.edu/nmt_1_intro . Sterkowicz cites the Polish translation of the verdict and its grounds, published as “Wyrok wraz z uzasadnieniem Amerykańskiego Trybunału Wojskowego Nr 1 w z dnia 20 sierpnia 1947 r.” Introduction by Józef Bogusz and Władysław Wolter, in Biuletyn Głównej Komisji Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce, 1970, Vol. XX, p. 13–187.

Schmaltz, Florian. 2017. “Chemical weapons research on soldiers and concentration camp inmates in Nazi Germany,” One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences. Bretislav Friedrich, Dieter Hoffmann, Jürgen Renn, Florian Schmaltz, and Martin Wolf (eds.). Springer, 229-258. Online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321327577_One_Hundred_Years_of_Chemical_Warfare_Research_Deployment_Consequences.

Trzebinski, Alfred. Statement made by Alfred Trzebinski before the court in the criminal proceedings against the defendants in the Neuengamme trial. Das Curiohaus Prozess gegen die Hauptantwortlichen des K.Z. Neuengamme. Transcript in the possession of Stanisław Sterkowicz.

Vereinigung Kinder vom Bullenhuser Damm e.V. The association’s website at http://www.kinder-vom-bullenhuser-damm.de

VVN-Bund der Antifaschistischen “Erinnert Euch.” Mimeograph, n.d. (a copy in the possession of Stanisław Sterkowicz)

Verbrechen an KZ-Häftlinge. Die Zeugen im Hauptprozess zum KZ Neuengamme. Online at http://media.offenes-archiv.de/Rathausausstellung_2017_Curio_10.pdf.

Wackernagel, Günther. [Account of Neuengamme, by G. Wackernagel, formerly a male nurse in that concentration camp; a copy in the possession of Stanisław Sterkowicz].

Zapisy terroru. Chronicles of Terror. Online at https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra

Publications

Heissmeyer, Kurt. 1943. “Grundsätzliches über Gegenwarts- und Zukunftsaufgaben der Lungenheilstätte.” Zeitschrift für Tuberkulose. 90: 34.

Heissmeyer, Kurt. 1943. “Grundsätzliches zum Aufgabenkreis der nachgehenden Fürsorge in der Tuberkulosebekämpfung,” Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 33/34: 598-600.

Heissmeyer, Kurt. 1943. “Erfahrungen über gemeinsame Werkdienstbehandlung Tuberkulöser und Nichttuberkulöser in Hohenlychen,” Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 33/38: 667.

Jakubik, Andrzej, and Ryn, Zdzisław Jan. 1973. “Eksperymenty pseudomedyczne w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 63–72. Original Polish version online on this website, https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/polish/171123,volume-1973 and English version, “Pseudo-medical experiments in Hitler’s concentration camps,” on this website,https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/170062,pseudo-medical-experimens-in-hitlers-concentration-camps

Klee, Ernst. 2001. Deutsche Medizin im Dritten Reich. Karrieren vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt-am-Main: S. Fischer.

Klee, Ernst. 2007. Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt-am-Main: S. Fischer.

Kłodziński, Stanisław. 1962. “Zbrodnicze eksperymenty z zakresu gruźlicy dokonywane w hitlerowskich obozach koncentracyjnych w czasie II wojny światowej.”Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 77–81. Original Polish version online on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/polish/171119,volume-1969, and English version, “Criminal tuberculosis experiments conducted in Nazi German concentration camps during the Second World War.” https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/259881,criminal-tuberculosis-experiments-conducted-in-nazi-german-concentration-camps-during-the-second-world-war.

Kłodziński, Stanisław. 1969. “Zbrodnicze doświadczenia z zakresu gruźlicy w Neuengamme. Działalność Kurta Meyera.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 86–91. Original Polish version online on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/polish/171119,volume-1969, and English version forthcoming.

Kłodziński, Stanisław. 1973. “Verbrecherische Tuberkuloseexperimente im Konzentrationslager Neuengamme.” Ermüdung und vorzeitiges Altern. Folge der Extrembelastungen. V. Internationaler Medizinischer Kongress der FIR, 21. bis 24. September 1970 in Paris. Leipzig: Barth. 347–349.

Lifton, Robert Jay. 1986. The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books, Inc.

Ryn, Zdzisław J., “Lekarze-więźniowie w Auschwitz-Bikrenau,” Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej 2009: 4(99).

Suchowiak, Bogdan. 1973. Neuengamme. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo MON.

Schafft, Gretchen E. 2004. From Racism to Genocide. Anthropology in the Third Reich. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

“SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt Heissberg.” https://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=67121

Weindling, Paul. 2003. “Genetik und Menschenversuche in Deutschland, 1940 – 1950. Hans Nachtsheim, die Kaninchen von Dahlem und die Kinder von Bullenhuser Damm.” Rassenforschung an Kaiser-Wilhelm-Instituten vor und nach 1933. Hans-Walter Schmuhl (ed.) Wallstein Verlag. 245–274.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.