Author

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English.

Dr Helena Szlapak, a well-known Kraków physician, social activist, World War II resistance combatant, and promoter of planned motherhood, died in Kraków on 31 March 1984 and was buried in Rakowicki Cemetery. People liked her, but knew very little about her life and achievements, because she was a very modest person.

She was born on 4 December 1898 in Brunary Niższe, a small place in the Gorlice region, as the thirteenth child of Albin Szlapak and his wife Tekla née Adamowska. Her father ran a country sawmill, and died when Helena was six. Helena went to school in Grybów and later in Kraków, where she attended and finished an eight-year classical gimnazjum (grammar school), though I have not managed to find out when she passed the matura school-leaving examination. In 1927 she graduated in Medicine from the Jagiellonian University. When she was a student, she was supported by her brother, except for the last two years of her studies, when she earned a living of her own. She advanced her professional experience in gynaecology and obstetrics, paediatrics, surgery, internal medicine, medical chemistry, and bacteriology. She was active as a practising and successful physician virtually to the end of her life, earning the admiration of her patients and enjoying the reputation of a highly respected doctor.

When the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, Dr Szlapak was working as a physician for the social insurance company Ubezpieczalnia Społeczna and also held an appointment as a medical office in a factory. She left Kraków as a refugee,1 but on her return lost no time in joining the local resistance movement associated with the People’s Guard of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS).2 The Kraków branch of the PPS was under the leadership of its district workers’ committee, with Józef Cyrankiewicz3 as its secretary. Dr Szlapak was also involved in resistance activities conducted together with Teresa Lasocka-Estreicher4 and Patronat, a group that organised aid for the inmates of the Montelupich prison, other jails and places of torture in Kraków, and in Auschwitz. She provided medical treatment for members of the resistance movement and made her apartment at No. 12 on ul. Garbarska available as a venue for secret meetings and other resistance activities. She was involved in a variety of resistance operations, such as the distribution of the underground press, the production of forged ID cards and documents, offering a safe haven for individuals on the German wanted list, and running an underground communications network.

Dr Szlapak was involved in establishing a clandestine communication system for Adam Rysiewicz5 (nom-de-guerre Teodor), leader of a local PPS resistance unit, and Maria Dziurzyńska, a clerk in the Kraków Arbeitsamt,6 thanks to which members of the resistance managed to destroy the personal records of Polish citizens due to be deported to Germany for slave labour.

She also participated in the rescue of Dr Tadeusz Orzelski7 from the clutches of the Gestapo. Orzelski was an Auschwitz prisoner whom the Gestapo had brought in to Kraków for interrogation, but due to his poor state of health put him in the dermatology ward of St. Lazarus’ Hospital.8 A resistance group devised a successful scheme to abduct him from the hospital. Dr Szlapak helped by lacing a packet of cigarettes with hashish to sedate the policeman who was guarding the prisoner.

Dr Szlapak wrote a fairly short, unpublished account of her involvement in other similar operations, such as the successful rescue and treatment of Marian Bomba,9 leader of the Kraków unit of the PPS People’s Guard. Bomba was seriously wounded in a Gestapo street ambush.

.Obverse of the medal conferred on Dr Helena Szlapak in 1981. The inscription in Hebrew and French above her name says “The Jewish People in Acknowledgement.” The French circumscription in the lower part of the medal says “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.” Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1985.

Those who needed Dr Szlapak’s assistance were not only the wounded, but also others in a variety of dangerous situations in which Poles engaged in combat against the German invaders could find themselves. One of the groups at risk were young people, who had to be protected against deportation to Germany for slave labour, as well as against oppressive measures at home from the Germans occupying Poland. In her private apartment, flat number 6, ul. Garbarska 12, Dr Szlapak ran a surgery, and administered injections to those in trouble, bringing about a dramatic rise in body temperature and making them appear to be suffering from an infectious disease.

She had contacts in Auschwitz, and her activities ranged from receiving kites (secret messages smuggled in and out of the camp), sending in food, medications, poison pills (cyanide), and other items such as wigs to help prisoners escape. She procured the wigs from Wacław Hemzaczek,10 the stage manager of the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre, which at the time was in German hands, playing only for Germans. She knew a lot about what was going on in Auschwitz and handled documents smuggled out of the camp, so she was a chain in the link of information reaching the world at large about the genocide. She continued to be in touch with Cyrankiewicz, who was her nephew, after his arrest in April 1941 and later deportation to Auschwitz (September 1942). He maintained his resistance activities in the camp. Dr Szlapak preserved a collection of documents connected with Auschwitz, which have come down to us.

.Reverse side of the Medal. The circular inscription in Hebrew gives the same motto as the Talmud quote on the obverse, “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.” Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1985.

The most important document relating to Dr Szlapak’s life during the War is her own story, which Dr Jerzy Brandhuber, as associate of the Auschwitz Museum, took down on 16 June 1963. I shall quote a passage from this document, so to speak giving the floor to Dr Szlapak herself, for an insight into what was going on in the resistance movement in Kraków:

In late September 1939, when I returned home to Kraków from my trek,11 I found my nephew Józef Cyrankiewicz in my flat at Number 12, ul. Garbarska. He was using it as a venue for secret meetings with lots of other PPS activists and their liaison officers. Members of the PPS resistance group continued to use my flat for this purpose right until Cyrankiewicz’s arrest in April 1941. I remember three of the numerous people who came to my flat, Stefan Rzeźnik,12 Józef Woźniakowski,13 and Mieczysław Bobrowski.14 Prior to Cyrankiewicz’s arrest my part in the underground resistance was not very big, I only carried out tasks I was instructed to do.

My flat was good for a secret meeting place, because during the War I was a district doctor and a lot of patients came to my surgery, so the frequent visits by members of the underground resistance went unnoticed.

After Cyrankiewicz’s arrest, when he was in Montelupich prison, we kept in touch with him and sent him food and small sums of money. Apart from the official allowance of food we could send, we also used the services of a Gestapo man called Friedrich to smuggle in an extra quantity and pass on kites. Friedrich’s services were procured by Zygmunt Kłopotowski15 who worked with us for a certain time; later he was sent to the concentration camp. During one of his visits to my flat, Kłopotowski recognised one of my patients, a Polish officer called Matowski, who he knew was an informer, and warned me about him. This officer frequently came to my surgery for treatment, and when he was waiting for his turn, he’d sit in the waiting room reading a paper and observing everyone who came in. After the warning, I told him his treatment had finished and got rid of him.

My first contact with Cyrankiewicz when he was in Auschwitz was established by means of a letter he sent from the camp.16 In it he wrote of a sweetheart and asked me to send his regards to her, which intrigued me, but in reality this was how he passed on the contact address to me. I gave the letter to Stefan Rzeźnik. The address he mentioned in his letter was one of the contact places we used to send kites to Auschwitz.

After Cyrankiewicz’s arrest, I met Adam Rysiewicz, who I think must have held a leading position in the underground organisation [he was the secretary of the district workers’ committee of the Kraków branch of the PPS—S.K.].

Teresa Lasocka and Rysiewicz met each other in my flat, and started visiting me. I didn’t know Lasocka before. Lasocka had contacts in Auschwitz, and when she had decoded the kites she received, she would bring them to me, and then we would work together to carry out the instructions and requests in them. At the time I didn’t know who delivered these secret messages. As far as I was concerned, I got them from Lasocka. I now know that Danuta Bystroń (now Pytlikowa)17 handled the delivery of kites, and that they were brought to Kraków by “Magda” Kieres Motykowa, but I don’t know who she passed them on to. Rysiewicz visited me very often. I only knew him by his nom-de-guerre, “Teodor,” and it was only after the War that I learned his real name.

The people who visited me in matters concerning Auschwitz were Rysiewicz, Lasocka, Edward Hałoń,18 and Rzeźnik. Liaison girls Marysia Mariańska, Róża Osiek-Ruszkowska, and “Basia” (later Kowalczykowa) also visited me. Forged Kennkarten (German ID cards) were made in my flat. One of the chief tools required for this business was a set of seals and stamps. The fakes were made by a graphic designer. When the Kennkarten were ready, the liaison girls would collect them from a network of hidey-holes used specially for this purpose. Marysia, who is now my home help, was in the know and managed the collection of the Kennkarten and other materials. We made counterfeit Kennkarten for PPS activists and persons in danger of being arrested or deported to Germany. They were also made for the Home Army.19

I tried to get medications for Auschwitz and brought them over from the social insurance institution. Rysiewicz took them from my flat and passed them on or delivered them himself to the concentration camp. We also sent in doses of poison on request. Poison pills were needed by prisoners planning an escape, in the event of being caught.

Rysiewicz procured the poison, potassium cyanide—I don’t know where he obtained it from—and after it had been checked by Prof. Jan Zygmunt Robel,20 Rysiewicz brought it to my flat, packed it, got the packages ready for transportation, and then took them away. There were six doses left when that period in my life came to an end, and I am going to send them to the Auschwitz Museum.

I obtained a couple of wigs from the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre and sent them to the camp. They were to make it more difficult to identify fugitive prisoners, who would otherwise have been easy to spot because they all had their hair cropped very short. Kazimierz Hałoń used one of these wigs for his escape.

Rysiewicz was a phenomenal boy. He was full of energy and had fantastic ideas. When he was in Kraków, he came round to my place every day. On a few occasions he showed me his backpack, which had been riddled with bullets during a combat operation. He wept whenever any of his men were killed in action. He took a very thorough approach to underground resistance business. Although I saw him every day and worked with him, I never knew anything about the operations he was about to conduct. He’d only tell me about them once he had carried them out.

One day, I inadvertently exposed him to a serious risk. At the time he was suffering from boils in the armpits. We used to cut them, but I wanted to stop new ones from forming and decided to apply a series of injections. I didn’t know he was about to go up to Auschwitz, and gave him an injection of Propidon,21 which causes a rise in body temperature. He left in the evening, and when he was in the Planty Gardens,22 he developed a fever and passed out. He had some confidential materials on him. When he came round, he was on a bench in the Gardens. He realised what had happened and found that he still had the secret materials on him. He got up and continued on his way to accomplish his mission on the same night.

At first Rysiewicz avoided contact with the Home Army. It wasn’t until later that he got in touch with them, probably for a mutual project to identify people in the service of the Gestapo. It was done by comparing and cross-checking the lists of names both parties had, for the purpose of identifying those due for execution.23

We were also in contact with Żurowska of the Home Army’s Military Archives and often did business with her.

I remember an incident connected with Rysiewicz. When “Basia” the liaison girl, one of whose contacts was Marian Bomba, was on her way to Rysiewicz, she noticed that the house where Bomba lived was surrounded by Gestapo men. She stopped for a while and overheard one of them saying his name, which told her that they were out for Bomba.

In this assassination attempt Bomba was shot in the thigh, and took refuge at Rysiewicz’s [or more precisely, in a hidey-hole where the two of them met—S.K.]. The Gestapo surrounded the building and embarked on a house search. When they got to the hideout flat, they started banging on the door. Those inside kept quiet. The concierge [a young woman—S.K.} came out and told the search party that the young man who lived in the flat had gone out and no one was in. The Gestapo men went away. Rysiewicz [and Bomba—S.K.] had kites and photos on them. They could neither destroy nor burn them, because smoke from the chimney would have given them away, so they ate a lot of paper and photos [the photos were on microfilm—S.K.]. When the Gestapo had gone, the combat unit was alerted and removed the wounded Bomba to Podgórze,24 where he was put in a hidey-hole in an air raid shelter in one of the houses [in the German army barracks on ul. Zamojskiego—S.K.].

“Basia” came running to me to fetch a doctor to remove the bullet. It was urgent and had to be done as soon as possible, so that no-one should see the wounded man in the shelter. After a few attempts, I finally reached Dr Jan Kowalczyk,25 whose wife was a prisoner in Auschwitz at the time. He agreed at once, and just said, “Let’s go.” I replied that first he had to get his instruments ready, to which he declared that they were ready and took his doctor’s bag. We left. It was obvious that it wasn’t the first time he was doing this kind of service. He always had his instruments ready for emergencies of this kind. We went by tram. When we reached the stop where we were to alight, I noticed Kazimierz Hałoń standing there. We waited for Rysiewicz, who was late. Finally, he arrived and took Dr Kowalczyk. I went home, and didn’t even know where they went. . . .

Rysiewicz had stomach trouble after eating the kites and photographs [microfilms—S.K.].

When we tried to help Cyrankiewicz escape from Auschwitz—both attempts failed—we had to get a hiding place for his mother.26 On the first occasion, when we received a secret message from Auschwitz that the escape was being planned, I had my sister admitted to St. John’s Hospital27 for an appendicitis operation, which I managed to persuade my sister she needed. She stayed in hospital for several weeks. On the second occasion, I rented a flat for her on ul. Starowiślna (now ul. Bohaterów Stalingradu).28 She spent a few weeks there.

During this second abortive attempt Rysiewicz and two of his colleagues were killed. It was an irreparable loss for us. For a short time his duties were taken over by Władysław Wójcik,29 who visited me a couple of times.

We tried a few times to procure Cyrankiewicz’s release from Auschwitz, but unfortunately all of our efforts were abortive. They only resulted in tremendous financial costs. I made one more attempt when he was in the Bunker.30 I had the address of a certain German, but he could not help.

One of the matters directly relating to Auschwitz that I remember concerned a plan to effect a large-scale break-out. I took part in one of the planners’ meetings, which was held in the flat of Dr Józef Garbień’s31 brother on ul. Karmelicka. Garbień had contacts in the Home Army. I remember some of the people who attended that meeting, Siemiginiewicz nom-de-guerre Wiktor, a Home Army intelligence officer, and Teresa Lasocka. We discussed the basic question, whether we should go ahead with the operation, and if so, when. We decided to put it on hold.

We learned that the Germans were planning to destroy Auschwitz. I remember that Lasocka brought a kite with this information and a demand that it should be immediately sent abroad. We were shocked and decided to send the news to London via our secret radio transmitter, with the demand that in retaliation German prisoners-of-war should be treated as hostages. I went to Żurowska with a copy of the secret letter, so that the Home Army could forward the information as well. I learned that three days later Churchill mentioned this barbarous plan in the House of Commons.

I saw a list of Auschwitz inmates who were informers. The only name I can remember from this list is Dorosiewicz.32

I read a kite with a word-for-word report of a conversation Cyrankiewicz had with Liebenhenschel,33 the commandant of Auschwitz. One of the things he told him was that he was the first prisoner to speak directly to the commandant.

Various lists and schedules arrived, which I transcribed or had transcribed by other people. It was a time when a lot of materials arrived, so I was very busy.

We ran an operation code-named PWOK34 to provide aid for concentration camp prisoners. The project was dubbed PWOK in my flat, and we were hoping to extend it to cover other concentration camps apart from Auschwitz, but did not manage to accomplish this aim.

Most of the secret messages from Auschwitz I saw were sent either by Cyrankiewicz himself, or on his orders. Perhaps Lasocka had other kites as well. I can’t remember whether or not they were signed by Kłodziński. When Cyrankiewicz was in the Bunker, someone else wrote kites for him.

I buried all the kites and photographs I received in the garden of Cyrankiewicz’s mother’s house on ul. Salwatorska.35 A German had moved into the house and occupied most of it, but let my sister use two rooms upstairs and part of the garden. We cultivated this patch. Rysiewicz packed the kites in tin boxes which he sealed with a soldering iron and later buried in the garden when he was working on the vegetable patch.

After the liberation we dug the boxes up. They and their contents (the kites and photos, including photos of Birkenau and heaps of bodies being burned) were unscathed when we retrieved them. I gave them back to Cyrankiewicz.

This account was taken down by Jerzy Brandhuber, curator of the Auschwitz State Museum.

Numerous honours and distinctions were conferred on Helena Szlapak, most of them for her wartime record. She was awarded the Knights’ Cross36 (1959), the Officers’ Cross37 (1960), the Order of Polonia Restituta,38 and the Righteous Among the Nations Medal (1983).

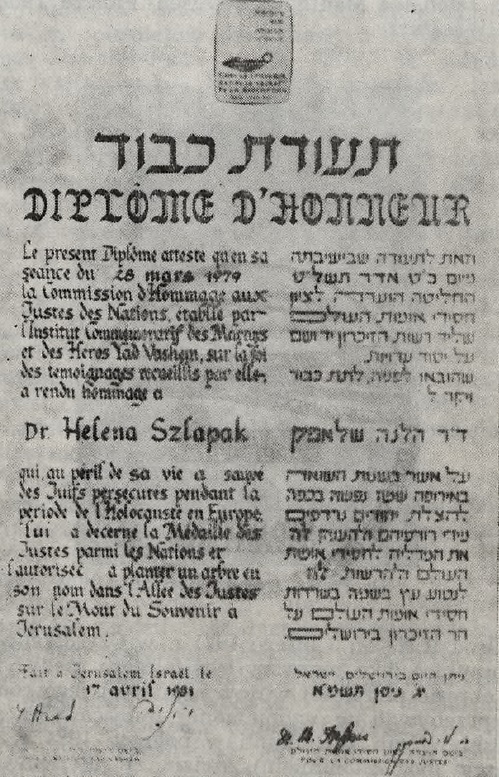

The certificate accompanying Dr Szlapak’s Yad Vashem medal. The bilingual text is arranged in two columns, with the left-hand column in French and the right-hand column in Hebrew. The emblem at the top bears an inscription reading “Remembrance is the Secret of Redemption.” The English version of the text is: “This is to certify that in its session of 28 March 1979, the Commission for the Designation of the Righteous Established by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Heroes & Martyrs’ Remembrance Authority, on the basis of evidence presented before it, has decided to honour Dr Helena Szlapak, who, during the Holocaust period in Europe, risked her life to save persecuted Jews. The Commission, therefore, has accorded her with the Medal of the Righteous Among the Nations and authorised her to plant a tree in her name in the Avenue of the Righteous on the Hill of Remembrance. Given in Jerusalem, on 17 April, 1981.” [The trees are planted on the Mount of Olives.]45 Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1985.

Dr Szlapak was circumspect and equable, to the very end of her life continuing her professional work and her involvement in social and political affairs, and taking a sound and open-minded attitude to people and their problems. After the War she continued to take an active part in the PPS and its affairs. She was also involved in the work of the Polish Red Cross, trade unions, professional associations, and medical societies (she was an honorary member of the Polish Gynaecological Society39), the Women’s League,40 and the Society for Family Development.41 Dr Szlapak found the time for all of these matters and was known for her level-headed and critical attitude. She appreciated the value of Poland’s medical chambers, which should be restored.42

Dr Szlapak joined the PZPR when the PPS was amalgamated with the PPR.43

She joined ZBoWiD44 in July 1957.

Dr Szlapak was proud of being a member of the Society for Family Development. In November 1957 she set up an advisory centre for the Society and ran it until December 1962. Later she was head of the Society’s specialist centre at No. 6 on Kraków’s Main Market Square. She was Honorary Chairwoman of the Society’s Kraków branch. When she died, the Society published an obituary notice in the papers, alongside the private obituaries from her family and friends.

Dr Helena Szlapak rendered distinguished service and was deeply committed to Kraków, its people and its culture.

On 3 April 1984, the day she was laid to rest in the Rakowicki Cemetery, the following words were spoken in a funeral oration at her graveside:

Dr Helena Szlapak was an activist with a deep commitment to public affairs. During the Second World War she was a combatant in the resistance movement and she looked after and provided aid to Auschwitz inmates and other victimised individuals. . . . For the whole of her life she was dedicated to action on behalf of society and service to her three great passions—Poland, socialism, and medicine.

***

Translated from original article: S. Kłodziński, “Dr Helena Szlapak.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1985.

Notes- When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, thousands fled east, the men to join the Polish forces in the east of the country. But when Soviet forces invaded on 17 September, many refugees returned home.

- PPS, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, was a large political party with several wings or splinter groups spanning a broad ideological range from moderately socialist to radical or almost communist views.

- Józef Cyrankiewicz (1911–1989)—a prominent member of the PPS before the War, involved in the wartime underground resistance movement both at liberty and when held in Auschwitz. After the War Cyrankiewicz joined the PZPR (Communist) Party and served for many years as Prime Minister of People’s Poland.

- Teresa Lasocka-Estreicher (1922-1974). The English translation of her wartime biography will shortly appear on this website.

- Adam Rysiewicz (1918-1944). Leader of a Socialist resistance group in Kraków, killed during an incident at a suburban railway station. More information on him at http://przystanekhistoria.pl/pa2/tematy/polacy-ratujacy-zydow/68775,Przywodca-konspiracji-socjalistycznej-w-Krakowie-w-latach-1939-1944-Sprawiedliwy.html.

- German for “employment exchange”. The main business these offices handled in Occupied Poland was the deportation of Polish citizens to Germany for slave labour.

- Tadeusz Orzelski (1894-1953). Director of Kraków’s municipal water company, associated with the Wisła football club. Member of the PPS and combatant in the resistance movement during the War. More information on him at http://historiawisly.pl/wiki/index.php?title=Tadeusz_Orzelski.

- Szpital św. Łazarza.

- Marian Bomba (1897-1960). PPS member and underground resistance fighter Turing the War. Took part in the Żegota project to provide assistance to Jews. More information at https://krakow.ipn.gov.pl/pl4/aktualnosci/62746,Malopolscy-Bohaterowie-Niepodleglosci-Marian-Bomba-1897-1960-Pepeesiak-w-walkach.html.

- Wacław Hemzaczek (1892-1951) actor, stage manager, and theatre director. For more information, see http://www.encyklopediateatru.pl/osoby/38494/waclaw-hemzaczek.

- The article was originally published in 1985.

- Stefan Rzeźnik (1902-1976). Member of the PPS, underground resistance combatant during the War, associated with the Cracovia football club. For more information, see https://www.wikipasy.pl/Stefan_Rzeźnik; http://krakowianie1939-56.mhk.pl/pl/archiwum,1,rzeznik,6425.chtm".

- Józef Stanisław Antoni Woźniakowski (1885-1943). Eminent lawyer, member of the PPS, underground resistance combatant during the War, sent to Auschwitz and executed at Death Wall. More information at http://krakowianie1939-56.mhk.pl/pl/archiwum,1,wozniakowski,3897.chtm.

- Marian Mieczysław Bobrowski (1877–1945). Member of the PPS, underground resistance combatant during the War, Żegota activist providing assistance for Jews. More information at http://krakowianie1939-56.mhk.pl/pl/archiwum,1,bobrowski,4449.chtm and https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polska_Partia_Socjalistyczna-_Wolność,_Równość,_Niepodległość.

- Zygmunt Kłopotowski (1900-1965). Major in the Polish Army. PPS member and combatant in the Home Army during the War. Arrested and deported to Auschwitz. More information: http://krakowianie1939-56.mhk.pl/pl/archiwum,1,klopotowski,1565.chtm.

- Concentration camp prisoners were allowed to send and receive correspondence written in German according to an approved scheme. Their mail had to be passed by the censorship office in the camp. Cf. Sylwia Przewoźnik, “Korespondencja więźniów z obozu w Auschwitz w świetle akt Sądu Grodzkiego w Krakowie z lat 1946-1950,” Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne, LXX-2018-1: 335-344, pp. 340, 341, 343; https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/162597657.pdf. Miejsce pamięci Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau. Zasoby. Korespondencja. http://www.auschwitz.org/muzeum/archiwum/zasoby.

- Danuta Bystroń and her fiancé Władysław Pytlik were PPS members who lived in Brzeszcze, a small place in the neighbourhood of the concentration camp. Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Escapes and reports. http://auschwitz.org/en/history/resistance/escapes-and-reports.

- Edward Hałoń (1921-2012). An inhabitant of Brzeszcze and PPS member; wrote reports for the Polish government-in-exile and helped to organise escapes. Author of W cieniu Auschwitz (2003), on the resistance movement in the environs of the concentration camp. See https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hałoń and https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/W_cieniu_Auschwitz.

- The Home Army, Armia Krajowa (AK), was the main and largest of the Polish underground resistance organisations. As a rule, it did not conduct joint operations with other groups, such as the Socialist Gwardia Ludowa (People’s Guard) on a regular basis (except for the People’s Guard of PPS-WRN—The Freedom-Equality-Independence splinter group of the PPS). In 1942 a Soviet-oriented Gwardia Ludowa was established, with a Communist membership. This group was hostile to the AK. Cf. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gwardia_Ludowa_WRN; https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gwardia_Ludowa.

- Dr Jan Zygmunt Robel (1886-1962), Polish chemist and forensic scientist, Jagiellonian University academic. Imprisoned by the NKVD after the War for his work on the team of experts examining the Katyn Massacre. See https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Robel.

- Propidon—a medication for the treatment of boils and other infections, often applied as a vaccine.

- The Planty Gardens are a ring of municipal parks encircling the medieval city centre of Kraków. They were laid out in the 19th century after the demolition of the city’s medieval fortifications. See https://youtu.be/SFEYRVI8dX0.

- The Polish Underground State operating in Occupied Poland during the Second World War had an underground judicial system. Its underground courts passed death sentences on collaborators, which were carried out by members of the armed resistance, generally Home Army men. Seehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special_Courts.

- Podgórze—a south-bank district of Kraków.

- Dr Jan Kowalczyk (1903-1958), husband of Prof. Janina Kowalczykowa, whose biography is on this website. For its English version, see S. Kłodziński, “Professor Janina Kowalczykowa.”

- Dr Szlapak’s sister Regina Cyrankiewicz née Szlapak (1880-1969).

- Szpital Bonifratrów—a hospital in Kraków run by the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of God.

- The name of this street now is Starowiślna, but under the People’s Republic, when this text was published, it was known as Bohaterów Stalingradu (“Heroes of Stalingrad Street”). After the fall of the Communist regime it reverted to its old name, which alludes to the old riverbed, along which the street was laid out following the late 19th-century adjustment of the Vistula channel. Surprisingly, the Germans did not change the name of this major thoroughfare, as they did with many other street names (e.g. under Nazi German occupation Kraków’s Main Market Square was known as “Adolf-Hitler-Platz”).

- Władysław Wójcik (nom-de-guerre “Żegociński”) was the secretary of PPS-WRN and a member of the local authorities of the underground resistance movement in Kraków. In 1944 he was the chairman of Żegota, the largest Polish organization providing assistance to Jews. Cf. Polska Podziemna Delegatura Rządu na Kraj. Okręgowa Delegatura Kraków. Część II. Online at http://www.dws-xip.pl/PW/RPDEL/pw31.html.

- The Bunker of Auschwitz was a dungeon for solitary confinement. Few inmates survived it.

- Dr Józef Garbień (1896-1954)—physician, soldier and football player, a member of Poland’s national soccer team. Cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Józef_Garbień.

- Stanisław Dorosiewicz. Dorosiewicz’s activities as an informer are confirmed in the statement made after the War by survivor Edward Liszka (b. 1920) on Chronicles of Terror (English translation available).

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Arthur Liebenhenschel (1901-1948), Nazi German war criminal. Commandant of Auschwitz I (the main camp of Auschwitz), succeeding Rudolf Höss in December 1943 until Höss’ return in May 1944. Arrested by the Americans after the War, extradited to Poland, stood trial before the Polish Supreme Tribunal, convicted of war crimes, sentenced to death, and executed. Ernst Klee, Das Kulturlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. S. Fischer: Frankfurt-am-Main, 2007. Hermann Langbein, “The Auschwitz Trials: Background and Overview (1947-1968).” English version of Der Auschwitz-Prozess: eine Documentation, (1965); Brand, in Yad Vashem Bulletin, 15 (1964), 43–117. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/background-and-overview-of-the-auschwitz-trials.

- Pomoc Więźniom Obozów Koncentracyjnych (Polish for “Aid for Concentration Camp Prisoners”).

- For pictures of the Cyrankiewicz family home, see https://aordycz-krakow.blogspot.com/2019.

- Krzyż Kawalerski.

- Krzyż Oficerski.

- Order Odrodzenia Polski.

- Polskie Towarzystwo Ginekologiczne. Now known as the Polish Society of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (Polskie Towarzystwo Ginekologów i Położników).

- Liga Kobiet.

- This is the organisation’s current name in English (its Polish equivalent is Towarzystwo Rozwoju Rodziny). This article uses the association’s old name, Towarzystwo Świadomego Macierzyństwa (the Society for Planned Motherhood).

- The Communists closed down the Polish medical chambers (izby lekarskie) in 1952. They were not restored until the fall of the Communist regime in 1989. See https://nil.org.pl/dzialalnosc/izby-okregowe.

- Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, the Polish United Workers’ Party (the Communist Party that held power in People’s Poland), was founded in 1948 through the enforced amalgamation of PPS with PPR (the Polish Workers’ Party, a communist group). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_United_Workers’_Party.

- ZBoWiD, Związek Bojowników o Wolność i Demokrację (the Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy), the main Polish war veterans’ association under the People’s Republic.

- This is an earlier version of the certificate, and does not mention the inscription of the holder’s name on the Wall of Honour.

Notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

This biographical article has been compiled on the basis of the following sources:

- Documents written by Dr Helena Szlapak

- A list of her awards and distinctions (a one-page typescript with handwritten additions);

- “Okupacja” (a four-page typewritten annex about her life during the War, appended to her CV written in 1971);

- “Relacja” (a six-page transcript of Dr Szlapak’s account of her life during the War, as related to J. Brandhuber on 16 June 1963);

- Dr Szlapak’s CV (a dense, one-page typescript);

- Dr Szlapak’s CV (a four-page, fairly dense typescript);

- Dr Szlapak’s CV (a seven-page, fairly dense typescript dated February 1983);

- Miscellaneous

- Certificate No. 734474 issued on 18 April 1983 by the Kraków branch of ZBoWiD confirming that Dr Szlapak was a war veteran;

- Document No. IV-8520-107(985)84, issued by the Auschwitz State Museum on 11 April 1984, with an appended photocopy of Dr Szlapak’s wartime story, as related to J. Brandhuber;

- Dr Szlapak’s obituary notice compiled by Stanisław Kłodziński for publication in the press (a three-page typescript);

- The farewell delivered by the master of ceremonies at the graveside of Dr Szlapak on the day of her funeral (a short, untitled text typed on one page);

- Obituary notices published in the press (Życie Warszawy and Dziennik Polski);

- Dr Szlapak’s obituary entitled “Nad mogiłą dr Heleny Szlapak: w hołdzie Człowiekowi,” published in Gazeta Krakowska (1984, No. 81, 4 April, p. 4);

- Dr Szlapak’s obituary entitled “Dr Helena Szlapak. Z kroniki żałobnej” published in Echo Krakowa (1984, No. 69, April, p.3);

- Oral information and comments on the draft for this article, from Danuta Kozubowa and Alicja Konopelska née Bomba.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.