Author

Stanisława Gogołowska, Survivor of Auschwitz–Birkenau (No. 64144), Ravensbrück (No. 46669), and Buchenwald (No. 27568).

Along with all the Polish physicians, pharmacists, dentists, and nurses whose lives were disrupted by the ordeals of the War in occupied Poland and the concentration camps, Polish medical students make up yet another group whose stories deserve biographical commemoration. Jerzy Antoni Mysakowski was one of these medical students. He has been mentioned in an article by Prof. Helena Mysakowska on the wartime experiences of the group of doctors and nurses treating TB patients in the city of Lublin (“Z okupacyjnych losów przeciwgruźliczej lubelskiej służby zdrowia,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1976); and by Prof. Józef Piasecki, quoted in an article by Zenon Jagoda, Stanisław Kłodziński, and Jan Masłowski entitled “Przyjaźnie oświęcimskie” (Auschwitz friendships; Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1978, p. 57). Nonetheless, Jerzy Antoni merits a biographical note of his own.

Jerzy Antoni Mysakowski, a medical student of the University of Warsaw Medical Faculty, in his Polish Army uniform. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1979. Click the image to enlarge.

Jerzy Antoni Mysakowski was born on 13 March 1919 in Tarnawatka, which was in the Powiat1 of Tomaszów at the time, into a family which cherished progressive and Polish patriotic traditions and brought Jerzy Antoni up in this spirit. When Germany invaded Poland, Jerzy Antoni was a third-year student of medicine at the University of Warsaw. He was called up and sent to serve as a medical cadet on a frontline sanitary train. He experienced the terrors of combat and the deep tragedy and bitter taste of Poland’s defeat in its defence campaign of September 1939. When the fighting was over, he managed to return home, but he did not stay there for long.

Almost straightaway after coming home, he joined in the work of the Polish resistance movement. He left home for Tomaszów Lubelski and got a job in the surgical ward of the local powiat hospital, where he looked after wounded Polish soldiers and officers in hiding from the Germans, who were on the prowl for Polish combatants. Dr. Janusz Peter,2 the hospital’s chief physician, a social activist with a reputation for patriotism, had many talents. He was a good diplomat and spoke fluent German, so he had good rapport with the German authorities. They trusted him and it would have never crossed their minds that Dr. Peter had turned his hospital into a safe haven for people on their wanted list and that he was helping Polish resistance fighters.

His young age notwithstanding, Jerzy Mysakowski was well prepared for the resistance work in which he engaged because he had attended a cadet college before the War, as Prof. Mysakowska wrote in her article. Moreover, his character had been tried and tested in the defence campaign of September 1939. When he felt that the ground under his feet was starting to give way in Tomaszów, he left for Lublin, where he got a job in the municipal hospital. Apart from the patients he attended “officially,” he also treated his “private” patients, wounded resistance fighters secretly brought into the hospital from the forest. There were also situations when he attended sick prisoners brought in from the Gestapo prison. On a few occasions Jerzy managed to arrange a successful escape, despite the vigilance of the prison guard supposed to be watching the prisoner.

Eventually, the Gestapo started to suspect Jerzy and sent a spy into the hospital to sniff him out. At this precise time, the Gestapo dispatched Prince Czetwertyński,3 a prisoner in a very serious condition, to the hospital. To prevent his escape, he was watched day and night by a prison guard. The snooper noticed that Mysakowski was seeing Czetweryński very often and notified his superiors in the Gestapo, which linked this information with the previous escapes. Jerzy sensed a storm brewing ahead and in the nick of time managed to warn “whom it might concern,” risking his own life.

On 3 September the Gestapo arrested him and took him straight from the hospital to Pod Zegarem (the Clock), its notorious torture chamber. He was tortured and kept in a dungeon for ten days, after which time they transferred him to Lublin Castle, which they were using as a prison. There he was thrown into the infamous Baszta (Bastille), which was reserved for the worst sort of “criminals.” He had been battered so badly that he had to be put in the prison hospital. But he was not allowed to stay there for long, and was soon sent back to the Bastille. From there he was taken back to the Clock on an almost daily basis for interrogation. Yet the violence and tortured, he did not disclose anything or give away any names. Thanks to the services of Dr. Jan Kostecki, who worked in Lublin Castle, Jerzy’s family learned of his heroic conduct and received a secret letter from him, which said, “Mum, don’t try to get me out, because it won’t work and you’ll only lose your health.”

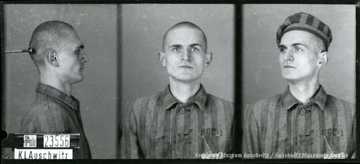

Auschwitz mugshots of Jerzy Antoni Mysakowski. Source: Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Click the image to enlarge.

On 27 November he was sent to Auschwitz. After less than three weeks in Auschwitz, he was on the brink of turning into a Muselmann,4 when by pure chance he met Prof. Piasecki, who had been his teacher before the War. Piasecki was shocked to see his former pupil in such a condition and decided to help him. By this time, Piasecki had been confined in the camp for a fairly long time and was one of the Auschwitz “veterans.” He was in the camp’s orchestra and knew his way about the camp. He took care of his ex–pupil straightaway, providing him with better clothing and extra food, and lifting his spirits. Soon there were good results; it was probably thanks to his teacher that Mysakowski landed a job in “Kanada.”5 Now Jerzy could help fellow–prisoners, and continued to do so when he was working in the prisoners’ hospital.

On 25 October 1942 he wrote a letter to his parents. Like every Auschwitz inmate, he started it with the official, obligatory formula, “I’m in good health and doing well.” There was nothing about this letter which went beyond the regulations, yet something about it carried a sense of nostalgia and that he would soon die. Jerzy asked about his family and friends, and wanted them to write as often as possible, twice a month, as he was longing for news from home. He ended the letter with something like a farewell: “ God is almighty and He will protect you...“

Three days later, during the morning roll call on 28 October 1942, the clerk of Jerzy’s block read out the names and numbers of about a dozen prisoners who had arrived from Lublin. One of them was No. 23556, Jerzy Mysakowski. He told them to stand on the left side of the block. At the same time prisoners from Lublin and its area were called out in other blocks as well. A total of 270 were selected. A rumour went round that they were to be taken to Block 3, where they were to identify members of a Lublin resistance group on photos sent to the camp by the Gestapo.

After the roll call all the prisoners marched out to work as usual, except for those whose names and numbers had been called out and told to stand aside. They were ordered to line up in a column and taken to Block 3. Here is the account of what happened next given by Eugeniusz Plewa, prisoner no. 23528, who was an eye-witness:

We were working on the construction of an extra storey in Block 13 . . . I was standing on a raised platform, with a trowel in my hand, so I could see practically everything that happened to those prisoners standing in a column. Around eight o’clock they were counted once more and sent out in the direction of the gate. They marched in rows of five, and when they were near Block 15, they were told to turn left, onto the main street leading past the kitchen and into the interior of the camp. At the same time scores of armed SS men entered the camp and instantly surrounded the entire column, which numbered around 300 prisoners. The commander of the operation was the SS man Palitzsch,6 a notorious villain, who was marching at the top of the column, leading them down the street for Block 11.7 When they had passed Block 21, a hospital block, and turned left, I noticed that as they marched the prisoners started to throw out all sorts of things that they had on them, even bread.

Some of the prisoners tried to escape, but the SS men soon cottoned on to that, and a barrage of rifle butts promptly went down on prisoners’ heads and backs. In spite of the resistance, the SS men used brutal force to finally bring all of them into the yard of Block 11... After a while you could hear the loud singing of the national anthem Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła (Poland has not perished), followed by the patriotic hymn Boże coś Polskę (O God, Who hast preserved Poland throughout the ages) ...

After a few minutes the singing stopped and again you could hear the SS men yelling. Later I learned that the prisoners were forcibly herded into the basement of Block 11. Once inside, they were ordered to strip and then led out a few at a time and made to stand against the black wall. Palitzsch and the other SS men murdered them with a bullet in the back of the head... Evidently, the murders did not proceed without disturbances. There were long intermissions between the rounds of execution... It was not until around three in the afternoon that everything went quiet and Palitzsch and the SS men left the camp. A Rollwagen8 full of bodies with blood dripping from them left the yard of Death Block. It rolled along the street in the direction of Block 3, the same block that the unfortunate victims of the massacre had passed only a few hours before.

Mysakowski was 23 when he was killed in front of Death Wall in the main camp of Auschwitz. Right to the end of his ordeal he persevered in the patriotic attitude and active defiance of his persecutors. He left a glorious legacy in the memories of his fellow–prisoners, many of whom owed their survival to him.

*

This potted biography has been compiled on the basis of the publications, statements and oral accounts mentioned above, documents and information from Kazimiera Mysakowska, Jerzy’s mother, and from his father’s sister, Professor Helena Mysakowska of Lublin.

***

Translated from original article: Gogołowska, S., “Jerzy Antoni Mysakowski.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1979.

Notes

- In Poland the second-tier territorial administrative unit is called a powiat.

- Janusz Wincenty Peter (1891–1963), Polish physician. Veteran of the Fist World War; joined the Polish Army in 1919 and fought in the Third Silesian Uprising. Rendered distinguished service for his region and in the underground resistance movement during the Second World War. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janusz_Peter and http://www.ttr-tomaszow.pl/patron.html

- Seweryn Czetwertyński (1873–1945 ), Polish aristocrat and pre-war politician. Arrested by the Gestapo in 1941 and held first in prison in Lublin, and later sent to Auschwitz and Buchenwald, which he survived but died two months after liberation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seweryn_Franciszek_%C5%9Awiatope%C5%82k-Czetwerty%C5%84ski

- Muselmann (pl. Muselmänner), “Muslim.” In the Auschwitz prisoners’ jargon, “Muslims” were prisoners whose physical and mental condition had deteriorated so much that they were on the verge of death. See Z.J. Ryn, “The rhythm of death in the concentration camp” (the subchapter on “The death of a Muselmann”) on this website.

- “Kanada” (Canada) was a special storage facility. On arrival at the ramp, Jewish prisoners had to strip and leave their clothes and belongings behind before being killed in the gas chamber. Later their belongings were searched by a commando of prisoners who had to look for gold and other valuables concealed in the discarded items. The valuables were then stored in the Kanada warehouses, while the discarded items were incinerated in a special facility. The SS guards shot any prisoner caught stealing anything from the piles of discarded clothing. For more information and a bibliography, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanada_warehouses,_Auschwitz

- SS-Hauptscharführer Gerhard Palitzsch (1917-1944). German war criminal. Conducted thousands of executions in Block 11. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerhard_Palitzsch

- The yard in front of Block 11, “Death Block,” was where scheduled executions took place. Prisoners sentenced to death were held in the dungeons of Block 11.

- The Rollwagen was a wooden handcart pulled by prisoners, often used in German concentration camps to dispose of dead bodies by taking them to the crematorium.

Notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.