Author

Stanisław Kłodziński, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Kraków Medical Academy, Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, Auschwitz survivor (No. 20019). Wikipedia article in English.

Dr Ignacy Kwarta, a distinctive and fascinating character, deserves to be described in a separate, extensive biographical article, because of his committed and resolute conduct and his outstanding personality. He was a physician and social activist, and a member of the PPS.1 Incarceration in Auschwitz ruined his health, and he died shortly after the War, before he could spread his wings and attain the ideals he had fought for. He has been mentioned several times in various publications; here we want to focus on his conduct during the German occupation of Poland and his imprisonment in Auschwitz as well as to supplement his biography with some significant details.

Ignacy Kwarta as a young man. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1978.. Click the image to enlarge.

Ignacy Kwarta was born on 25 July 1898 in Poczapińce,2 into a farmer’s family. His parents were Jakub and Maria née Kowal. He attended primary school in his native village and then went to a nearby grammar school in Tarnopol.3 However, he had to discontinue his education when the First World War broke out. He volunteered to join the Austrian army. In 1916 he was staying in Vienna and on 26 February of that year passed his school-leaving examinations with a group of students from Austrian Galicia,4 who were allowed to take them in Polish. Thanks to that, on 20 October 1919, he was able to commence his university studies in medicine, which he had long planned to do. However, prior to that happy turn, during the military operations in the region of Lwów,5 he sustained a gunshot wound in the right arm, which was broken and damaged by the shrapnel. For years to come, Kwarta would suffer from the after-effects of that injury, as evidenced in an X-ray photo taken in the Polish Military Medical School6 hospital.

Dr Wojciech Wacław Musiał and Krzysztof Urbański, journalists from Kielce who have written about Ignacy Kwarta, say that when he recovered, he studied at the Medical Faculty of the John Casimir University in Lwów. In 1923 he was granted a one-year scholarship from the Polish Ministry of Military Affairs. On 4 December 1924 he received the degree of Doctor Medicinae Universae7 and, as he had been a beneficiary of a scholarship awarded by the Ministry of Military Affairs, he was assigned a post in the Border Defence Corps,8 a military unit created in 1924.

Even as a young man, Dr Kwarta had to face difficult situations and take dramatic decisions likely to jeopardise his career. For instance, in late 1927, when a Ukrainian peasant was shot by the soldiers of the Corps, Captain Kwarta was asked to issue a false death certificate. When he refused, there were reprisals: he was accused of having fallen under the influence of the PPS and Communists9 and, instead of keeping company with the military stationed in the area, he was fraternising with the local inhabitants.10 Due to the harassment, he had to find employment elsewhere. Another conflict with his superior, the commander of the 6th Brigade of the Border Defence Corps, occurred when Lt. Kwarta was serving in the 24th Battalion of the Corps in Sejny. He wanted to use his leave entitlement, as on 6 February 1927 he was due to marry Maria Emilia Michałkiewicz in Jarocin.11 However, his request was turned down for no reason but to aggravate him, so Kwarta left to get married. He returned to Sejny with his bride and was immediately put under house arrest for a fortnight. He spent the following two weeks in jail in the fortress of Grodno.12

Finally, he left the army in the rank of captain13 and took a training course at the National School of Hygiene14 in Warsaw at Chocimska 24 to become a powiat15 physician (3 September 1928–24 March 1929). Shortly afterwards, he and his family moved to Pomerania and settled in the town of Świecie.16 Throughout that period, he was supporting his mother. Although he lived in Świecie, he often visited Jarocin, his wife’s hometown, where he established a branch of a youth association called Wici.17

He soon became one of the recognised and most respected inhabitants of Świecie. He had a kind, friendly, and gentle manner with patients, was known for his accurate diagnoses, good treatment, and medical intuition. He saw poor patients free of charge and often gave them money for food and medicines. Dr Kwarta worked in Świecie for over four years, until 30 August 1933.

As a powiat physician, Dr Kwarta had his living quarters in the building that housed the powiat authorities. Yet, ignoring the fact that he was a public servant, he hosted Stanisław Dubois,18 a left-wing politician, after one of his public addresses in Świecie. The local press used the occasion to launch an attack on Kwarta, castigating him for his pro-Communist views.

Dr Kwarta was deeply committed to voluntary work for the community: he chaired the local branch of the Polish Red Cross, trained four teams of rescue paramedics, gave dozens of political addresses, and was active in the Airborne and Anti-Gas Defence League,19 the reserve officers’ club, the TB prevention committee, and the powiat committee20 for physical education and military training. He was also engaged in the work of the local Workers’ University Association.21 The Second Department22 considered Dr Kwarta a Communist and freethinker, which provided the grounds for his prosecution on political charges. Dr Kwarta and Kazimierz Rusinek23 published a few24 pamphlets which they signed “Sierp i Młotek” (“Hammer and Sickle”), on the Church, the popes, and Poland, religion and socialism, and the popes and independence.

Dr Kwarta proved his mettle and openly declared his reservations on the general atmosphere in Poland when the country was governed by the supporters of Piłsudski.25 In everyday conversations, he liked to engage in political debates, pointing out the drawbacks of the political system of the time, its inequality and injustice, and the need for radical reform. His public addresses tapped a similar vein and were full of Communist ideology. Dr Kwarta delivered one of his talks in the autumn of 1932 in Julian Borkowski’s restaurant in Nowe Miasto, a small place in the Powiat of Świecie. A secret police officer who witnessed the event reported that Kwarta had declared that “capitalism was defunct.” The prosecutor’s office initiated an investigation, the secret police placed Kwarta under close surveillance, and when charges were brought against him, he lost his job. His lawyer was Dr Otto Pehr26 from Grudziądz, but Dr Kwarta was able to speak smartly and daringly in his own defence, for instance he even insisted that Józef Piłsudski be examined by a psychiatrist.

These interesting details were corroborated many years later by Kazimierz Rusinek, the pre-war secretary of the powiat committee of the PPS in Grudziądz. In his article entitled “Dubois,” published in the weekly Świat on 26 August 1962, he wrote that Dr Kwarta, a PPS member whose “political sentiments and views indicated he was a Communist and a valued physician and social activist,” stood in the dock in Grudziądz for defaming Marshal Piłsudski by calling him a “lunatic” during a political rally. Similar views about Piłsudski, whom his political opponents nicknamed “the Badger of Sulejówek,”27 were voiced by several other politicians before the coup of May 1926.28 Putting forward his motion, Dr Kwarta wanted to force the court to check if the statement was true. Of course his motion was rejected and he was put in jail.

Later Dr Kwarta moved to Warsaw, but the loss of reputation proved irreparable, despite the fact that eventually he was acquitted. More harassment ensued: he was put under regular surveillance and his home was searched on several occasions. During one of the night searches, even his little daughter Irenka was frisked, even though she swung her tiny fists at the intruders. The Ministry of Health systematically rejected Dr Kwarta’s applications for various medical appointments in different parts of Poland. I will cite a few of the numerous rejections. On 28 June 1929, Dr Stanisław Skalski, head of the Department of Public Health in the Łódź Voivodeship29 Office, wrote, “In reply to your letter of 27 June, currently there are no vacancies for powiat physicians in the Voivodeship of Łódź.” On 22 July 1929, in reply to Dr Kwarta’s enquiry about a powiat physician’s appointment, the office of the Voivode of Tarnopol wrote that his request could not be granted, because there were no vacancies in the region.

We may cite another official letter, sent to Dr Kwarta by Dr Stefan Hubicki, the Social Welfare Minister, on 29 October 1933:

As the Grudziądz Regional Prosecutor’s Office has initiated criminal proceedings against you on the grounds of Article 65b of the Polish Civil Service Act of 17 February 1922, I hereby suspend you from your duties with immediate effect.

At the time, Dr Kwarta was employed as a clerk in that Ministry. Tired of all those setbacks, he decided to leave Warsaw and on 15 August 1934 finally managed to obtain an appointment as a powiat physician in Jędrzejów. His colleagues-to-be threw a welcoming party for him and Dr Kwarta hired a band that played The Internationale for him. In Jędrzejów, Dr Kwarta became as popular as in Świecie. He improved his qualifications by attending training courses and studying specialist literature. He was called “the Judym of Jędrzejów.”30 He continued his political and community work and did not change his views, so he co-operated with the Communists, Socialists, and the peasants’ leaders, established and supported a local branch of the Workers’ University Association in Jędrzejów, and kept in touch with Wici and the Association of Freethinkers.31 Dr Kwarta also vouched for doctors against whom the Polish Supreme Medical Court was conducting an inquiry concerning professional liability. He used every opportunity to propagate his political opinions, for instance when he cheered up feeble-looking army conscripts by promising them that their lives would change for the better [when the Communists seized power] and they would have enough sausage and oranges to eat. So a new stack of letters denouncing him was piling up.

On 2 November 1934 the prosecutor opened a new case. Dr Kwarta was suddenly arrested and imprisoned in Kielce Castle. On 9 November, Dr Dziadosz, the Voivode of Kielce, notified him that he was suspended due to his “provisional” detention and that as of 1 December 1934 he would be receiving half his pay. Dr Kwarta expected to get a sentence of a few years in jail. So he went on hunger strike for a fortnight and distributed the contents of his food parcels among his fellow inmates. He was picked on even in prison. As the prosecutor wanted to break Dr Kwarta, he ordered solitary confinement for him, isolated off from other prisoners, especially Communists. Stefan Przeździecki, a Communist32 who was held in the same prison at the time, told me in March 1976 that he remembered that during exercise in the prison yard, which lasted a quarter of an hour and was taken twice a day, he used to see Dr Kwarta being watched by a guard and kept ten metres away from other prisoners.

Public opinion in the Kielce region was shocked and outraged by the discriminating practices of the authorities. The Socialist press wrote reports on Dr Kwarta’s hunger strike. His wife tried to obtain a reprieve and managed to contact President Ignacy Mościcki.33 She was also receiving letters of protest sent by Communists from France and other countries. Henryk Jabłoński,34 chairman of the Warsaw branch of the Freethinkers’ Association, offered her financial support. On 22 January 1935, the prosecutor gave in to popular demand and dropped the charges against Dr Kwarta, who stayed in Jędrzejów, continued his education as well as his previous political and social mission, gave lectures and ran medical courses for young people. He attended May Day celebrations in Warsaw and took part in the workers’ marches which started in front of the Ateneum theatre.

It should be noted that Dr Kwarta, who was active in many milieus, took special care of sick teachers and children. His widow remembers an incident involving a little girl who had been bitten by an adder. It took Dr Kwarta plenty of time and effort to rescue her from the hands of the ignorant crowd: the local people believed the girl would recover if she was buried up to the waist. He often used a primitive horse cart with a bale of straw for a seat to travel across the countryside over the bumpy roads of the former Russian Partition.35 He would stay with his patient for as long as necessary, until the sick man was well provided for.

Life went on as usual until September 1939. Dr Kwarta was a war invalid, so he did not take part in the fighting against the German invasion, but he was in the reserve force. He organised medical services in Jędrzejów for casualties, especially a hospital. In the early days of the War, he was one of those who managed to contain the panic that erupted when the town was bombed. In the autumn of 1939, the Germans searched his home and held him hostage for a fortnight in the municipal detention centre. During the search, many of his books and other objects were confiscated. Dr Kwarta was harassed and put under surveillance; he was banned from leaving the town and seeing his patients at night. Instead, after dark, he was continually checked up on by German military police patrols. All the time he was under stress, fearing another imprisonment, but he carried on with his usual work, having adopted appropriate safety measures. The Germans forced him to move house three times and after each eviction he was given worse and worse accommodation. Dr Kwarta provided medical aid to anyone in need of it; he treated one of the “Silent Unseen36 Men,” and other resistance fighters. Whenever he heard that the Gestapo had arrested a family’s breadwinner, he helped the relatives, usually by giving them money.

After the fighting against the German invaders and the initial shock following defeat, and the ensuing German reign of terror, the Communists and Socialists of Jędrzejów closed ranks and started their underground work. Dr Kwarta supported them and in April 1941 offered his flat on Wodzisławska as a venue for the first meeting of Młot i Sierp.37 The participants were Jerzy Wojciechowski, Antoni Patrzałek, Władysław Jureczko, Wacław Zielonka, and Marian Kubicki. The smallest cells of Młot i Sierp had five members and the person who maintained contact between the Jędrzejów branch and headquarters in Warsaw was Marian Kubicki, a member of the peasant movement. Stanisław Sędek, a young doctor, was another member of the Jędrzejów branch.

Wacław Zielonka sent me a letter dated 3 April 1976 saying that of course the local members of the organisation wanted to fight the Germans, but they also intended to shape public opinion and persuade people that the USSR supported the Polish working class and that, although it had formed an alliance with Nazi Germany,38 now, as a German-Soviet war seemed inevitable, it was going to defeat the Third Reich and bring freedom to Poland. When Germany invaded the USSR, Młot i Sierp formed a special unit to sabotage railway transport. However, the Gestapo learned of the group and suppressed it, having arrested several of its members. Dr Kwarta joined another organisation, Straż Chłopska (called Chłostra for short), which later evolved into the Peasant Battalions.39 He was a member until his arrest in 1942. Genowefa Sobolewska, one of his then comrades, informed me in a letter dated 18 April 1976 that she and Dr Kwarta listened in on and monitored the news broadcast by foreign radio stations and disseminated it.40 Dr Kwarta was fluent in German, which was an asset for his underground resistance activities. His flat was a venue for the illicit secondary school classes held within the Polish clandestine educational system.41 The six teachers involved in it were arrested by the Gestapo on 6 February 1942.

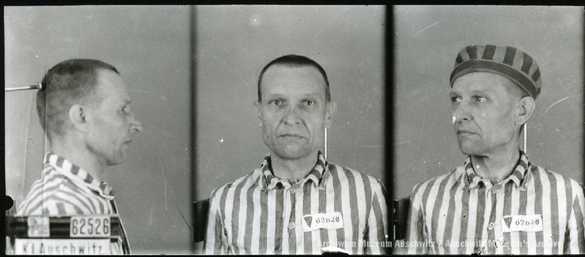

Ignacy Kwarta in an Auschwitz mug shot. Source: Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Click the image to enlarge.

On the night of 14/15 June, the Gestapo burst into Dr Kwarta’s lodgings, searched and looted them. He was arrested for being a Communist, held in the Kielce jail on Zamkowa, brutally interrogated and tortured, but he did not break down or rat on any of his associates. In the meantime, his family was ordered to leave Jędrzejów and its powiat within twelve hours. All of their property was confiscated. On 26 June 1942, Dr Kwarta’s wife Maria was notified in writing by the Kreishauptmann42 of Jędrzejów that on the orders of the Kielce Gestapo all the furniture in her flat had been “secured” and handed over to Reichsdeutsche.43

In her letter of 4 April 1976, Maria Kwarta explained the reasons for and circumstances of her husband’s arrest:

During the War, S.L., a driver, wrote a letter denouncing my husband, saying that he had been receiving payments in roubles from Moscow for his pro-Communist agitation and encouraging people to change the political system by means of a revolution. During the interrogations in the Kielce jail, he was brutally beaten up. He returned to his cell, and all of his body was battered black and blue.

Maria Kwarta went on to say that after the War Dr Kwarta was questioned about those events by the Polish secret police,44 but he did not want the informer prosecuted. In his opinion, recognising that his deed had a negative moral value was a sufficient punishment for a guilty man.

Various accounts and letters corroborate the fact that in jail Dr Kwarta was not dejected, but on the contrary, he cheered up his fellow inmates. He would invite new arrivals to sit on his mattress and instructed them how to behave under interrogation. He showed other prisoners the right way to behave and set a good example. For instance, initially everybody rushed to be served as soon as the food pot arrived, but he would stand aside and wait until all of his companions had received their rations. Later, when they got to know him better, they would have been embarrassed to push ahead of him. Instead, they tried to make themselves useful in many ways. Dr Kwarta was a very tolerant person and not judgemental. If someone transgressed, he tried to understand them, justify, and forgive the misdeed. This is why his fellow inmates had many warm feelings for him. Both in jail and later in Auschwitz, Dr Kwarta gave an example of how to uphold one’s human dignity.

On 1 September 1942, Dr Kwarta was put in a group of 514 prisoners from Kielce and Radom and deported to Auschwitz, where he was registered as political prisoner No. 62526. At first he had a very hard and exhausting job, regulating the Soła River. He ended up in the camp hospital and was admitted to Block No. 20. During the admission procedure he was selected for death by an SS physician, but saved by Dr Rudolf Diem, of whom I shall write later. When he got slightly better, he was kept on in the hospital in the capacity of an assistant nurse in Room 3, and later as the supervising physician of Room 3. His co-workers were two other prisoners: Józef Mężyk,45 a medical student, and myself. Although by that time his tuberculosis had advanced and his health had visibly deteriorated (he had lost a lot of weight), Dr Kwarta did not lose his optimism or go back on his convictions. He liked to join in discussions and propagate his leftist views, expecting Poland to become a state ruled by workers and peasants. He bravely worked in the hospital with a lot of dedication and shared his food parcels and meagre rations with fellow inmates. He was a popular and respected personality, as confirmed by survivors.

Here I would like to quote an unpublished opinion voiced by Dr Rudolf Diem, whom I have mentioned above, a prisoner doctor from Block 28 in Auschwitz:

It was probably in the autumn or late summer of 1942 that Marian Kubicki, who was in regular contact with me, brought Dr Kwarta and asked me to take care of him. He introduced him as a Wici member: the two of them used to work together for this organisation before the War. His Wici membership notwithstanding, I wanted to admit Dr Kwarta because he was a medical professional. He looked poorly and I suspected he had tuberculosis, so I told Adam Kuryłowicz that Dr Kwarta should not report for the Arztvormeldung.46 We took the risk, skipped the formality, and took him straight in to be treated in Block 20. There he was tended to by Dr Władysław Tondos, as far as I remember, and given the best care it was possible to give in the camp.

One day, Marian Kubicki came to me with a request: he wanted to visit Dr Kwarta in Block 20. When we arrived there, we saw him engaged in a lively conversation with his fellow patients on the shape of the future Polish state. We heard him say that Communism should be introduced as the political system, that wealthy landowners and factory owners should be done away with, and that the country should be ruled collectively. One of the participants in the discussion defended the landowners, saying they would guarantee agricultural productivity. Perhaps it was Dr Kwarta who replied that the best crops were yielded by farms of about 15 hectares. The debate was getting more and more heated, and I took part in it as well. As far as I remember, that was the last time I saw Dr Kwarta.

The working conditions in the hospital were difficult and I had just a short time for each patient, while examining him in the admissions room or talking to him while filling in his medical history, which had to be kept in German. Later on, patients were looked after by the nurses responsible for particular blocks and rooms. So I remember only the most unusual incidents involving sick prisoners who wanted to be admitted.

Dr Kwarta’s hospitalisation in Block 20 has been described by Józef Mężyk, his close friend and fellow inmate. Prior to his imprisonment in Auschwitz, Mężyk was a medical student, so he did a doctor’s job in the camp hospital. He is now living in Chicago. Here are passages from his letter to Maria Kwarta, sent from Belgium in 1947:

I met Dr Kwarta in November 1942, when he was working in the hospital room I supervised. He had become so exhausted by his shovelling job and starvation diarrhoea that he was actually selected for death in the gas chamber, although he did not realise that at the time. He was saved by Dr Diem of Warsaw. A few weeks after his admission to Block 20, he developed a lung condition. At first, we simply suspected pneumonia, but then it turned out he had tuberculosis. During the winter of 1942-1943 he was confined to his bed, and the food parcels you sent kept him alive.

In the spring of 1943, he started working as a doctor and soon earned the reputation of a good practitioner. I was a young enthusiast, and drew upon his experience most of all, and he did not mind passing his knowledge on to me. He had many friends among fellow inmates and was liked and esteemed by his colleagues, especially for his calmness and subtle but ready wit. In the summer of 1943, he felt well and worked as hard as he could to give me some respite: there were only two of us to a room with 180 patients and we had to fight fiercely for their lives, which was not an easy thing in the circumstances. We tried to have as many Poles as possible on the staff, while the Germans kept removing our best medical professionals from their jobs. The hospital was pestered with intrigues, blackmail, and denunciation, while we were at constant risk of serious infection and had to struggle against the odds, trying to avoid many traps that were laid for us, and to resolve everyday dilemmas.

Our work started at 6 a.m. and lasted until evening. Feeling responsible for the future of the prisoners’ children and other relatives, we never gave up our efforts and therefore our results were fairly good, sometimes better than those in regular hospitals.

It was in those days full of toil that I got to know your husband and became his friend, as the strongest bonds come from working and fighting together, and pursuing a common goal.

In the autumn of 1943, Dr Kwarta was unwell again and this time it was more serious. His tuberculosis had developed bilaterally, the pneumothorax proved ineffectual due to pulmonary adhesions, and the cavities grew larger. He lost his appetite, ran a fever, and what made matters worse was that he realised he was dying.

Although his condition was hopeless, he remained peaceful and his intellect continued to impress his fellow prisoners.

I did not see Dr Kwarta after August 1944, because I was incarcerated in the Bunker,47 having been denounced as a saboteur. I was accused of keeping healthy prisoners in the hospital to save them from evacuation west, into the depths of the collapsing Third Reich. The informers were German prisoners. . . . Luckily for me, the ultimate punishment was just a deportation to another camp in Germany. Many prisoners waved us good-bye from the hospital windows, and Dr Ignacy Kwarta was one of them. He has left a lasting memory as an honest and reliable man, whom I respected when he was alive and whom I honour after his death. . . .

My memories of the camp also include scraps of information about his daughter. Dr Kwarta shared the details with me and showed me her photograph: on it she was a girl of fourteen. I knew how dearly he loved her and how much he cherished the photo. This tough, uncompromising, and withdrawn man had his soft spots and vulnerabilities.

In the camp, neither Dr Kwarta nor the authors of these passages knew that his brother Władysław had been killed in action in 1944.

Dr Kwarta was too weak to join the evacuation march of Auschwitz prisoners to other camps, which began on 17-18 January 1945. He stayed behind, expecting to be killed with a group of other seriously ill inmates, whom he did not want to abandon.

Although he lived to see Russian troops liberating Auschwitz, he was swollen and emaciated. He was sent to Kraków by car and placed in St. Lazarus’ Hospital. Again he was not receiving enough food, because the establishment had meagre supplies. TB patients were slightly better off after they were moved to a specialist hospital for infectious diseases (Miejskie48 Zakłady Sanitarne at Prądnicka 80). Once a week they received a ration of Swedish crispbread, 100 grams of lard, 150 grams of honey, and 100 grams49 of cheese.

On 7 March 1945 Dr Kwarta’s old comrade Antoni Patrzałka arrived in Kraków to take him back to Jędrzejów and put him in the local hospital. Within a month, even though he was very ill, Dr Kwarta managed to deliver a few speeches (e.g. to the inhabitants of Jędrzejów assembled in the Gdynia cinema and to the representatives of workers and peasants who gathered from the entire powiat for a political meeting).

He had a nice, warm room in the hospital and was well fed. He hoped that with proper care and treatment he would recover and go back to work. On 14 March, Edward Feliś, the starost50 of Jędrzejów, appointed him head of the hospital and chair of the Powiat51 National Council, even though Dr Kwarta was unable to carry out his duties. In spite of his poor condition, he helped to draft a speech for the May Day celebrations. However, as his condition deteriorated and he developed cavernous TB in the right lung, he had to be taken back to Kraków for an operation, which was performed by Prof. Józef Glatzel52 and Dr Jan Kowalczyk.53 Dr Kwarta was hospitalised at Kopernika 9 from 24 April 1945 to 23 May 1945, the day he died. To the very end of his life, he was cheerful and patiently endured his suffering, so the nurses called him an angel.

Dr Kwarta’s funeral was attended by crowds of local people and will be remembered for long by the inhabitants of Jędrzejów. On 28 June 1945 the town’s National Council voted its resolution No. 5, which read: “In recognition of the exceptional achievements of the deceased Dr Ignacy Kwarta and in order to pay tribute to his flawless character and generous nature . . . [we have hereby decided that Prosta Street should be renamed after him54 and new signs be put up immediately with all due dignity, in the presence of the Jędrzejów National Council in corpore.”

Finally, we cannot ignore the fact that Dr Kwarta’s wife Maria was his faithful lifelong partner, who shared his political views, responsibilities, and concerns. She never gave up despite the trials and tribulations described above. Even at the bleakest times when her husband was imprisoned, she carried on his social and political efforts. On many occasions, sometimes successfully, she applied for his release from jail. Several times the couple lost their entire property and their library. As Dr Ignacy Kwarta had always wanted, she raised their daughter Irena up to be a conscientious citizen and made it possible for her to study medicine.

Dr Kwarta’s tombstone in Jędrzejów cemetery bears a short, but meaningful inscription:

Dr Ignacy Kwarta, physician, champion of the emancipation of workers and peasants, best caregiver to the sick, poor, and underprivileged, benefactor of this town and powiat, Auschwitz survivor. He shall live forever in our hearts and minds.

***

Translated from original article: Kłodziński, S. “Dr Ignacy Kwarta.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1978.

Notes

- PPS, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, the Polish Socialist Party.

- Now Pochapyntsi, Ukraine.

- Now Ternopil, Ukraine.

- From 1795 to 1918 Poland was not an independent country, but partitioned and ruled by three neighbouring powers, Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Galicia, the south-eastern part of Poland, was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

- Now Lviv, Ukraine. At the Peace Conference of Versailles after the First World War, Poland was restored as an independent state, but fighting went on between Poles and neighbouring national communities for the demarcation of the borders. The military operations meant here are probably the fighting for the city of Lwów and its region in 1918–1919 between the local Polish population and the Ukrainian community.

- Oficerska Szkoła Sanitarna.

- Doctor Medicinae Universae—the degree awarded in Poland at the time to graduates in medicine.

- The Border Defence Corps (Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza) was established to protect Poland’s eastern borderlands against continuous attacks by infiltrating guerrilla groups sent into Poland from the Soviet Union.

- The PPS was a legal and registered political party in Poland in the interwar period (see Note 1), but the Polish Communist Party (KPP) was delegalised after it sided with the Bolsheviks, who invaded Poland in 1920 and wanted to turn the country into a Bolshevik Soviet state.

- The eastern borderlands of pre-war Poland had a multiethnic population. Some of the region’s Ukrainian and Belarusian inhabitants engaged in anti-Polish activities, either because they wanted to set up their own national state in the area, or because they were sympathetic to the Soviet Union. This article glosses over such facts (see Notes 5, 8, and 9).

- Jarocin is a place in western Poland, hundreds of kilometres away from Sejny, which is now near Poland’s border with Lithuania.

- Now Hrodna, Belarus.

- Therefore he must have been demoted, since the year before he was a lieutenant.

- Państwowa Szkoła Higieny.

- In Poland the second-tier territorial administrative unit is called a powiat.

- Świecie is a small town in the north of Poland.

- Wici was a Polish rural youth organisation which operated from 1928 to 1948. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zwi%C4%85zek_M%C5%82odzie%C5%BCy_Wiejskiej_RP_%E2%80%9EWici%E2%80%9D

- Stanisław Dubois (1901–1942), Polish left-wing politician, journalist, and parliamentary deputy for the PPS. Veteran of the 1919 Silesian Uprising and the Polish-Bolshevik War of 1920. Dubois was a prominent opponent of the Sanacja military government of 1926–1939, and as such was one of the politicians imprisoned for their stalwart opposition. When the War broke out, Dubois served in the PPS underground resistance movement. The Germans arrested and imprisoned him in the Pawiak jail, and later sent him to Auschwitz, where he took part in the camp resistance movement and was executed in 1942. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanis%C5%82aw_Dubois

- The Airborne and Anti-Gas Defence League (Liga Obrony Powietrznej i Przeciwgazowej, LOPP) was a Polish paramilitary organisation founded in 1928 whose interests focused on aviation. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liga_Obrony_Powietrznej_i_Przeciwgazowej

- Powiatowy Komitet Przysposobienia Wojskowego i Wychowania Fizycznego.

- Towarzystwo Uniwersytetu Robotniczego (TUR), a socialist cultural and educational institution.

- The “Second Department” was the colloquial name for the Polish military intelligence and counterintelligence service.

- Kazimierz Rusinek (1905–1984), Polish left-wing politician, survivor of Stutthof and Mauthausen, after the Second World War a prominent member of the Communist government in People’s Poland. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kazimierz_Rusinek_(polityk)

- Original Polish titles: Kościół, papieże a Polska, Religia a socjalizm, and Papieże a niepodległość.a

- Józef Piłsudski (1867–1935), Marshal of Poland. One of the chief Polish military commanders to whom credit is due for the restoration of the country’s independence in 1918 and its successful defence against the Bolshevik invasion in 1920. A member of the PPS Socialist Party, Piłsudski was appointed First Marshal of Poland in 1920 and held the top position in the country’s government. He had bitter political antagonists, and in 1926, when he and his supporters were out of office, they staged a military coup. The Piłsudskiite military regime ran the country for the rest of the time until the outbreak of the War. Hated and reviled by the Communist rulers of People’s Poland (1944–1989), he is now generally regarded as a national hero for his contribution to the restoration of Polish independence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%B3zef_Pi%C5%82sudski

- Otto Pehr (1892–1963) was a Polish lawyer and a PPS member. Before the War he represented Socialists brought before the Polish courts on political charges. When the Soviet Union invaded Poland on 17 September 1939, Otto Pehr was one of hundreds of thousands of Poles deported to the Soviet Union and held in Soviet jails or gulags. In 1941, following the Sikorski-Maisky agreement after the Germans attacked the Soviet Union, Pehr and thousands of other Poles were released and served in the Polish Forces in the West. Otto Pehr spent the rest of his life in exile, taking an active part in the PPS activities there. Cf. Tadeusz Wolsza, “Misja gen. Władysława Andersa, Jozefa Lipskiego i Józefa Różańskiego w 1948 r.,” Dzieje Najnowsze XXXVIII (1996), 3-4: 122. Cf. http://rcin.org.pl/Content/46458/WA303_62582_A507-DN-R-28-3-4_Wolsza.pdf; https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komitet_Zagraniczny_PPS; https://www.nytimes.com/1963/12/08/archives/dr-otto-pehr-71-of-polish-exiles.html.

- Józef Piłsudski’s veterans built a country cottage for him at Sulejówek as a token of their gratitude to their commander-in-chief. In 1923 Piłsudski and his family moved in. Now the house accommodates the Józef Piłsudski Museum. https://muzeumpilsudski.pl/miejsce-2/https://muzeumpilsudski.pl/miejsce-2/. Borsuk, the Polish word for “badger,” also has a figurative meaning and stands for a taciturn, devious, and solitary person. It could also be a reference to Piłsudki’s long, silver, drooping moustache (cf. Słownik języka polskiego, https://sjp.pwn.pl/sjp/borsuk;2445760.html).

- See Note 25.

- A voivodeship is the first-tier territorial administrative division in Poland, and its chief administrative officer is called a voivode.

- A reference to Dr Judym, an altruistic physician in Stefan Żeromski’s novel Ludzie Bezdomni (Homeless People).

- Koło Wolnomyślicieli.

- Not to be confused with Stefan Przezdziecki, who was Poland’s ambassador to Italy at about this time.

- Ignacy Mościcki (1867–1946), professor of chemistry and inventor, President of Poland in 1926–1939.

- Henryk Jabłoński (1909–2003), Polish socialist, professor of History, and after the War a prominent member of the Communist government of People’s Poland.

- A reference to the times before 1918, when Poland was not an independent country, but partitioned for 123 years and ruled by three neighbouring powers, Russia, Prussia, and Austria. The Russian Partition was considered particularly backward.

- The Silent Unseen were paratroopers trained by Polish forces abroad for intelligence and resistance operations and dropped in occupied Poland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cichociemni

- Młot i Sierp (“The Hammer and Sickle”), a wartime Communist organisation in occupied Poland. http://www.andreovia.pl/po-roku-1918-4

- On 23 August 1939 the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, on the grounds of which they decided on a joint invasion of Poland, the Germans invading from the west on 1 September, and the Soviets from the east on 17 September and drawing up a demarcation line between their respective occupied territories of Poland. On 22 June 1941 Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, thereby ending their alliance. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Molotov%E2%80%93Ribbentrop_Pact

- Bataliony Chłopskie (the Peasant Battalions), an armed resistance organisation operating in Occupied Poland during World War II and associated with the PSL (Polish Peasants’ Party). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bataliony_Ch%C5%82opskie

- Under German law in occupied Poland, Poles were liable to severe penalties (including deportation to a concentration camp or death) for the mere possession of a radio. https://wiadomosci.dziennik.pl/historia/ciekawostki/artykuly/7685608,wyrok-posiadanie-radia-sowieci-wojskowy-sad-ii-wojna-swiatowa.html

- In line with their racist policy, the German authorities occupying Poland closed down all the country’s universities, colleges, and secondary schools. Polish educationalists set up a system of secret university and grammar school education.

- Kreishauptmann—title of the German chief official of what had been a Polish powiat and was now a German Kreis.

- Reichsdeutsche—Germans originating from the territories of the Third Reich proper.

- Urząd Bezpieczeństwa (UB), the secret police operating in the People’s Republic of Poland in 1944–1956. Generally, the work of UB focused on the anti-Communist underground resistance movement operating in post-war Poland, but sometimes during the Stalinist period they turned their attention to pre-war Communists whom they found suspicious and whose comrades had died in Stalin’s purges in the 1930s.

- Józef Mężyk (b. 1916), prisoner doctor and surgeon in Auschwitz (No. 18858); later transferred to Neuengamme, which he survived. After the War he lived in the USA. http://auschwitz.org/muzeum/o-dostepnych-danych/dokumenty-medyczne/chirurgie

- Die Arztvormeldung (German for “doctor’s preliminary review”). In Auschwitz the expression referred to the SS physician’s examination of prisoners applying for hospital admission. Any prisoners the SS physician considered too ill to recover (including all with TB or typhus) would be sent straight to the gas chamber or killed with a phenol injection.

- In Auschwitz the Bunker was a dungeon for solitary confinement. Few inmates survived it.

- This hospital is now known as the John Paul II Hospital in Kraków.

- The respective weights in ounces are 3.5 oz. (lard and cheese) and 5.3 oz. (honey).

- In Poland the chief administrative officer of a powiat is called a starost.

- Powiatowa Rada Narodowa.

- Józef Glatzel (1888–1954), Polish surgeon, professor of the Jagiellonian University Medical Faculty; active during the War in the Polish resistance movement.

- Dr Jan Kowalczyk (1903–1958), husband of prof. Janina Kowalczykowa, whose biography can be read here. See also Dr Jan Kowalczyk’s biography by Władysław Denikiewicz (in Danuta Pytlik et al. “Biographical notes . . .” and the biography of Dr Szlapak.

- On the grounds of the Prohibition of the Promotion of Communism and Other Totalitarian Regimes in the Names of Public Buildings and Other Public Facilities Act of 2016, the Institute of National Remembrance’s Committee for the Prosecution of Crimes Against the Polish Nation recommended the withdrawal of the street name “ulica Doktora Ignacego Kwarty.” The Committee ruled that as a pro-Soviet agitator and implementer of Communism, Ignacy Kwarta satisfied the definition in Art. 1 of the Act. The street has reverted to its old name and is now known as “ulica Prosta.” https://ipn.gov.pl/pl/upamietnianie/dekomunizacja/zmiany-nazw-ulic/nazwy-ulic/nazwy-do-zmiany/42155,ul-Kwarty-Ignacego.htmla

- In the original Polish article the next point is erroneously labelled e) instead of d), and point d) is erroneously labelled f).a

- Published as Mrok i mgła nad Auschwitz: wspomnienia więźnia nr 20017, 2019, Poznań: Replika.

a—notes by Marta Kapera, the translator of the text; remaining notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

- Various documents owned by Dr Ignacy Kwarta, such as:

- membership cards, baptism and marriage certificates, secondary school-leaving certificates, letters (especially those turning down his applications for employment), copies of official correspondence he had with institutions, his request for a leave of absence dated 7 January 1927, military orders dated 18 November 1927 and 18 April 1928, Dr Kwarta’s letter to his wife, dated 17 March 1945, and an X-ray report dated 4 April 1928;

- letters from the Ministry of Social Welfare to Dr Kwarta, reference numbers 3911/BP of 24 October 1933 and 3840/BP of 29 October 1933;

- a letter from the Voivode of Kielce to Dr Kwarta, reference number OLP. 3/K-100/5 of 9 November 1934;

- a letter from the Voivode of Tarnopol, reference number Pr. 2323/29 of 22 July 1929;

- the decision of the investigating judge of the Grudziądz Regional Court, reference number I.S. 13/33, Ds 2274/33, of 24 October 1933, authorising the search of the residence of Ignacy Kwarta as well as a body search; another decision of the same date saying legal proceedings are to be initiated against Dr Kwarta; and a decision dated 22 December 1933 to drop proceedings against him;

- the verdict of the Criminal Department of the Grudziądz Regional Court, reference number I.K. 431/33, sign. Ds 2274/33, acquitting Dr Kwarta.

- Głowa, Stanisław. Mrok i mgła obozu w Oświęcimiu [Darkness and fog in Auschwitz] (typescript, 94 pp.).

- An article entitled “Jednolitofrontowiec dr Ignacy Kwarta” in KPP 16 XII 1918 — PZPR 10 III 1959. Tadeusz Bartosz, Bolesław Dziatosz, Antoni Grygierczyk et al. (eds.), 1959, Kielce: Komitet Miejski Polskiej Zjednoczonej Partii Robotniczej, p.

- Kwarta, Maria. Wspomnienia o drze Kwarcie. (Photocopy of a manuscript in quarto format, 28 pp.)

- A letter from Józef Mężyk, Auschwitz survivor, to Dr Kwarta’s widow Maria, dated 22 July 1947.

- Letters and written statements I received from:

- Rudolf Diem (5 September 1976);

- Maria Kwarta (a series of letters dated 1975-1977);

- Ludwik Lech (25 February 1976);

- Roman Pańtak (29 March 1976);

- Stefan Przeździecki (1 April 1976);

- Kazimierz Rusinek (6 November 1976);

- Genowefa Sobolewska (18 April 1976);

- Wacław Zielonka (3 April 1976).

- Musiał, Wojciech Wacław, and Krzysztof Urbański, “Dr Ignacy Kwarta (1898- 1945) — Judym jędrzejowski.” Studia Kieleckie. Kwartalnik. Kielce 1976, 2 (10), pp. 187-191.

- Roszko, Janusz, and Stefan Bratkowski, Ostatki staropolskie.1966. Warszawa: Czytelnik, pp. 75 and 78-81.

- Rusinek, “Dubois.” Świat, 1962, issue 34, p. 8.

- Resolution No. 5, copy of the minutes of session No. 4 of the Jędrzejów National Council of 28 June 1945.

- Urbański, “Jędrzejowski Judym,” Słowo Ludu, 1974, issue 781.

- Węcewicz, S. “Doktor Ignacy Kwarta,” Służba Zdrowia, 1969, issue 4, p. 3.

- I also relied upon my personal memories of Dr Ignacy Kwarta, who was my fellow prisoner in Auschwitz and my colleague in Block 20 of the camp hospital.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.