Author

Stanisław Kłodziński, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Kraków Medical Academy, Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, Auschwitz survivor (No. 20019). Wikipedia article in English.

Dr. Witold Paweł Kulesza was an outstanding prisoner-doctor of Auschwitz-Birkenau, fully deserving of a memorial article. Dr. Edwin Opoczyński published a short note about him in the first issue of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim.1 Dr. Kulesza was Häftling-Oberarzt (chief prisoner doctor), and distinguished himself by the medical services he rendered to prisoners of diverse nationalities, chiefly in the Birkenau men’s camp but also in the Roma camp2,3 He was one of the few members of the medical staff who did not leave during the evacuation of Auschwitz-Birkenau in January 1945, but stayed in his post until the day of liberation.

Witold Paweł Kulesza was born on 22 March 1891 at Wysokie Mazowieckie into the family of Józef Kulesza and his wife Blandyna née Jaźwińska. Prof. Piotr Bańkowski, who attended the same Russian grammar school as Dr. Kulesza, writes that the Kulesza family had a fine record in the pro-independence movement.4 In 1905 Witold and his brother took part in a school strike. Witold attended the Polish secondary school in Łomża which trained its students for a career in business and trade, and left school in 1910 Witold. He had to earn his living, but continued his education. In 1913 at Kazan he passed the Russian school-leaving examination in foreign languages for external students and enrolled in the medical faculty of the local university. He graduated in 1917.

Prof. Józef Wacław Grott writes in a typescript obituary of Dr. Kulesza that during his time at University he was president of the illegal union of Polish students right until the time he was called up for military service {in the Russian army} and left for the front.5 He served on the citizens’ committee6 providing aid to Polish war victims who were refugees or had been resettled from areas where combat operations were going on.

On graduating in 1917, Dr. Kulesza was sent to serve in a regiment, and later in a hospital in the front-line zone. At this time he contracted typhus, which saved him from suffering from this disease later in Auschwitz. From September 1919 to November 1921 he served as a physician in the Polish Army.7 In the newly restored Polish State, he had his Russian graduation certificate nostrificated and in May 1922 settled in Wysokie Mazowieckie, where he established the local powiat8 hospital and was its chief physician until September 1939. He was a skilful manager and used the latest diagnostic methods in the hospital. He was known for his humanitarian approach to patient-physician relations and was good at steering clear of conflicts. He was popular with the local inhabitants, who looked up to him. Usually he was the only doctor on duty in the hospital, obliged to be on call continuously, standing by to handle emergencies requiring different kinds of specialist treatment. His work was very exhausting and eventually impaired his circulatory system.

Dr. Kulesza took an active part in the work of various social organisations. He was the spokesman of the Warsaw and Białystok branch of the Medical Chamber,9 and a member of the supervisory board of the Choroszcz mental hospital.10 He also participated in the work of the Polish Red Cross. The local community wanted him to run for election to parliament. Notwithstanding all his social work, he continued to further his education and qualifications. He spent his holidays working in the hospitals of Warsaw, developing his practical experience. At home he was an avid reader of the medical journals. He was involved in many aspects of public affairs: he set up a local amateur choir, he organised public events and meetings for special occasions such as memorials for combatants who fell in the 1863 Uprising.11

When World War Two broke out, Dr. Kulesza served in the defence campaign of September 1939 in the Polesie independent operational group12 commanded by Gen. Franciszek Kleeberg.13 In the late autumn of 1939 Dr. Kulesza moved to Ostrów Mazowiecka, which was in the border zone of the Generalgouvernement14 and the Nazi German security forces placed the area under rigorous guard. Dr. Kulesza worked in the town as a municipal physician. The Germans resettled large numbers of Polish people evicted from the annexed parts of Poland15 in this powiat. Dr. Kulesza provided medical and material aid to many of the resettled people. He also visited the municipal prison, where he helped political prisoners. He was a member of the Home Army16 and used to travel secretly to the local woods to treat wounded resistance fighters.

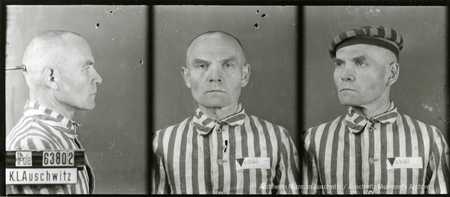

Dr Witold Kulesza’s mug shot from Auschwitz. Source: Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Click the image to enlarge.

Dr. Kulesza’s activities caught the attention of Gestapo agents. He was kept under surveillance and arrested on 17 May 1942. On 15 September 1942, after a four-month investigation and imprisonment in the Pawiak jail in Warsaw, he was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau and registered as political prisoner No. 63802. The few accounts that we have tell us that on his fifth day in Block 28 in Auschwitz I (the main camp), he was sent to Birkenau. We know that he worked in the men’s hospital there, and later transferred to Section BIIe, the Zigeunerlager (the Roma camp).17

Dr. Kulesza helped fellow prisoners, putting his life at stake on an everyday basis. Nonetheless, he managed to save many prisoners’ lives. Proof of this came after the War in numerous thank-you letters he received from survivors of various nations, practising various religions and holding different beliefs. His widow has preserved these letters. One of the people whose life he saved was Dr. Edward Stokowski, a physician, who was so debilitated that he had turned into a Muselmann.18 Dr. Kulesza took him into the prisoners’ hospital and gave him a job there. Dr. Kulesza also saved Dr. Herman from death by giving the SS physician a false diagnosis;19 he also saved Dr. Szor and many others.

There is a touching set of letters from Czech inmates whom Dr. Kulesza looked after in Birkenau. He had a gift for making friends, so he made friends with them, too. The collection of his thank-you letters includes correspondence from Drs. Štich, Janauch, and Cešpiva. In a letter dated 23 November 1947, Dr. ZdeněkŠtich,20 who was the Czechoslovak deputy minister of health at the time, wrote to Dr. Kulesza,

I couldn’t have celebrated Polish-Czech Friendship Week better than by thinking about you, the first Polish friend I made in the camp. Memories came back of those times when you lent me a merciful and helpful hand in those dreadful conditions. Could I ever forget the friendly advice you gave a young Czech doctor whose lack of experience was aggravated all the more by that cruel environment?

Dr. Štich recalls that Dr. Kulesza gave him extra food during a typhus epidemic, sharing his food parcels with other prisoners; that he attended him patiently in Block 2, helping the young Czech prisoner with bedsores to recover; and that he looked after the Roma children. Finally, he observed that “fraternal Poland had you as its first envoy to the Czechs.”

After the liberation of Auschwitz Dr. Kulesza returned to Ostrów Mazowiecka and resumed his post as chief physician of the municipal hospital. Unfortunately, his health, which had been ruined in Auschwitz-Birkenau, did not permit him to continue his medical career. In 1949 his cardiac condition following a second heart attack forced him to retire. From the autumn of 1949 Dr. Kulesza lived in Pruszków, where his wife, who managed the pharmacy of the local mental hospital, looked after him for the rest of his life. He died on 18 May 1957 and was buried in the local cemetery.

Dr. Kulesza has stayed in the memories of many Auschwitz survivors as a man of integrity and a brave, friendly, patient and cheerful, resolute and kind-hearted person, an excellent diagnostician and a first-rate medical practitioner.

***

Translated from original article: Kłodziński, S., “Dr Witold Paweł Kulesza.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1975.

Notes

- Opoczyński, Edwin. 1961. “Dr Witold Kulesza,” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 90–99. Information on Dr. Kulesza is available in several other sources, for instance by Mieczysław Bartniczak, “Eksterminacja ludności w powiecie Ostrów Mazowiecka w latach okupacji hitlerowskiej (1939-1944),” Rocznik Mazowiecki, Vol. V (in print) {Translator’s note: this volume was published in 1974}. In the typescript of his book on Stalag 324, entitled Obóz jeniecki w Grądach. Z dziejów stalagu 324 – Ostrów Mazowiecka, which he has deposited in Mazowiecki Ośrodek Badań Naukowych, a regional research Centre, Bartniczak writes that in June 1941 Dr. Kulesza provided medical treatment for Soviet POWs in the surgical department of Ostrów Hospital. {Translator’s note: An extended version of Bartniczak’s book, covering Stalag 333 as well, was published in 1978 by MON, the Polish Ministry of Defence publishers.}a

- The Zigeunerlager (the Sinti and Roma camp) was a separate part of Birkenau set up on orders from SS Dr Josef Mengele, who accommodated a group of Sinti and Roma families there and used them as human guinea pigs for his experiments. On 2 August 1944, after he had finished his experiments, he had them killed.b http://auschwitz.org/en/history/categories-of-prisoners/sinti-and-roma-gypsies-in-auschwitz

- See Szymański, Tadeusz; Danuta Szymańska; and Tadeusz Śnieszko, 1965, “O ‘szpitalu’ w obozie rodzinnym dla cyganów w Oświęcimiu-Brzezince.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim: 90–99, who write that Dr. Kulesza ran an internal diseases ward for women and children in Block 30. The ward also provided a maternity service and medical treatment for prisoners with diseases of the digestive system; in addition, it accommodated a “gynaecology and obstetrics outpatients’ clinic” (p. 93).a

- Poland lost its independence for 123 years from 1795 until the end of the First Word War, and its territory was partitioned and annexed by three neighbouring states (Russia, Prussia, and Austria). During this period Poles engaged in several uprisings and other pro-independence activities against the Partitioning Powers.b

- Dr. Kulesza was a subject of the Tsar of Russia at the time, so he was called up for service in the Russian Army.b

- During the First World War, as the Germans conducted an offensive into the western territories of Russia, the Russian authorities forcibly evacuated the largely Polish population east, leaving the people destitute. Social organisations stepped in to handle the welfare services the Russian government failed to provide.b

- Poland was restored as an independent state in November 1918, at the end of the First World War, but had to fight several wars with neighbours for the demarcation of its borders. One of these wars was with the Ukrainians inhabiting Poland’s eastern territories for Eastern Galicia (i.e. the City of Lwów and its region) in 1918; another was against the Bolsheviks, who invaded Poland in 1920. This article was published during the period when Poland was in the Soviet sphere of influence, and for reasons of censorship it is not explicit on this point. However, it is reasonable to assume that Dr. Kulesza served as a Polish army physician on one of these fronts.b

- Powiat – the term for a second-tier territorial administrative division in Poland.b

- Izba Lekarska Warszawsko-Białostocka.b

- Szpital Psychiatryczny w Choroszczy.b

- In 1863 the Poles in the Russian zone of Partitioned Poland rose up in a major insurrection against their Russian overlords. See Note 2 above. Veterans of the 1863 Uprising lived to see Poland recover its independence in 1918.b

- The Polesie independent operational group (Samodzielna Grupa Operacyjna Polesie) was a large Polish combat force fighting in the defence campaign of September 1939 against the German and Soviet invasions.b https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independent_Operational_Group_Polesie

- Franciszek Kleeberg (1888-1941), Brigadier-General in the Polish Army. The last Polish commanding officer to lay down arms at the end of Poland’s unsuccessful defence against the double invasion by Germany and the Soviet Union. His troops were fighting alternately against German and Soviet forces closing in on him. He died in German captivity.b https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franciszek_Kleeberg

- Das Generalgouvernement (GG) was the name the Germans gave the part of occupied Poland which they did not annex and incorporate in Germany. The GG was ruled by Hans Frank and a German administration.b

- When Germany invaded and occupied Poland in 1939, it annexed the western part of the country, which it called the “Reichsgau Wartheland” and incorporated this territory in the German Reich.b

- Armia Krajowa (AK, the Home Army) was the largest combat resistance organization in occupied Europe during the Second World War.b

- After a letter of 27 February 1974 from the State Auschwitz Museum in Oświęcim.a

- Muselmann (pl. Muselmänner, “Muslim”). In the Auschwitz prisoners’ jargon, Muselmänner were prisoners whose physical and mental condition had deteriorated so much that they were on the verge of death. See Z.J. Ryn, “The rhythm of death in the concentration camp” (the sub-chapter on “The death of a Muselmann”) on this website.b

- The management of German concentration camps had prisoners suffering from diseases such as TB or typhus killed in the gas chambers or with a phenol injection. To save such prisoners' lives, prisoner doctors used a number of ruses, one of them being entering fake diagnoses on prisoners' medical records.b

- Zdeněk Štich: (1928 - 2013), See a 1959 World Health Organisation document at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/40460/WHO_TRS_194.pdf;jsessionid=3218707A33FC29DD9CBCF9CD61CD6EB6?sequence=1.b

a—original notes translated from the Polish article; b—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

This potted biography of Dr. Witold Paweł Kulesza is based on the following sources:

- Letters from his widow, Janina Kuleszowa-Cieślawska née Gołębiowska, sent to me from London and dated 5 January and 19 February 1974;

- Letters from Auschwitz survivors and Dr. Kulesza’s patients, Halina Bartnicka, Jan Celiński, Dr. František Janauch, Irena Prosińska, Dr. Zdeněk Štich, Dr. Edward Stokowski, Dr. Szor, and Stefan Wierzejewski, sent to him after the War, copies of which I received from his widow;

- A photocopy of Prof. Józef Wacław Grott’s typewritten memorial of Dr. Kulesza;

- A note dated 23 February 1974 with information on Dr. Kulesza, which I received from Mieczysław Bartniczak, the historian of the Powiat of Ostrów Mazowiecka;

- A letter dated 13 April 1974, from Prof. Piotr Bańkowski;

- A letter dated 24 March 1974, from Dr. Leon Surówka of Ostrów Mazowiecka;

- Records from the Archive of the State Auschwitz Museum in Oświęcim;

- My personal recollections.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.