Author

Janusz Krzywicki, MD, PhD, dentist, university professor, president of the Polish Association of Stomatology (1958–1971), Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor No. 74593.

Injuries to the face and jaws were a common occurrence in Auschwitz. Some happened as a result of accidents while prisoners were at work or due to Allied bombing raids, but many injuries to the face and jaws were caused by violence from SS men, block functionaries, or kapos beating prisoners up. Prisoners’ heads and faces were one of the favourite targets for the “summary punishments” administered by the camp’s functionaries for apparent transgressions, misdemeanours, or for no reason at all.

A strong SS man could tear a prisoner’s eardrum if he punched or hit him on the head or face with a hard object such as a good stick, the handle of a spade, or the leg of a stool, or if he gave the prisoner a clout on the ear with a cupped hand. Alongside kicking a prisoner prostrated on the ground, this was one of the favourite types of “fun and games” Übermensche (“superhumans”) liked to play. So no wonder there were very many cases of prisoners getting their teeth broken, dislocated or knocked out, or their crestal bone, jaw or mandible (lower jawbone) broken.

We have no records for the way such injuries were treated before the end of 1942, so we cannot say much about these incidents except for assuming that the victim ended up in the gas chamber. It was not until late 1942 and the beginning of 1943 that things changed, when H-Zahnstation (the dentistry ward of the prisoners’ hospital) got ten beds for patients with jaw injuries. This happened thanks to the sympathetic attitude taken by Dr Władysław Dering, head of the hospital’s surgery department. From that time on, the future of prisoners with injured jaws radically changed for the better and they could look forward to receiving medical care and treatment from dentists looking after them on a day-to-day basis and helping them to recover.

Simple fractures of the teeth and cases complicated by pulp exposure were handled with the use of the generally practised methods of treatment, and often, once they had healed and been filled in, a crown would be applied. Displaced teeth would be repositioned and secured with a splint. Treatment would be administered if the pulp of a dislocated tooth went necrotic. The procedure did not always end in success: often a tooth would have to be removed if there was extensive damage to the periodontal tissue, whenever it survived but showed no signs of reintegration and was effectively a foreign body in the patient’s mouth.

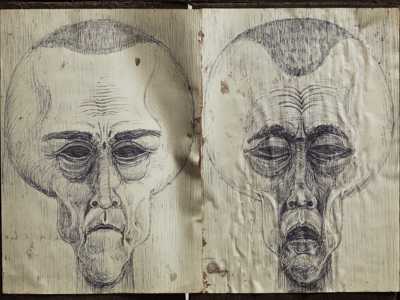

A Prisoner’s Face. Artwork by Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click the image to enlarge.

Cases of a fractured mandible (and sometimes but less often, fractures of the upper jaw) presented a considerable difficulty, especially in the early period when only primitive methods of treatment were available. Teeth being displaced or knocked out completely occurred far more frequently for the upper jaw (maxilla), while fractures were more common for the mandible (lower jaw). In almost all the case of a broken mandible, the splinters tended to undergo a considerable degree of displacement, and their relative position depended on the place where the fracture occurred, the fracture path and its relation to the muscle attachments, as well as the force causing the damage and its vector. Simple fragments under the impact of a well-developed set of muscles tended to be displaced more, while fractures along a central line counterbalanced by muscle resistance were displaced less or not at all, and could arise under the direct impact of the force causing the fracture.

In almost all the cases of a broken jaw, the fracture and its counterpart position on the opposite jaw were stabilised using a splint. The place opposite the fracture on the other jaw served as a point of orientation for the realignment of the broken pieces and restoration to their normal position. Elastic intermaxillary elastics were applied to achieve occlusion. Once maximum intercuspation was restored and confirmed using an X-ray, we could even apply a permanent metal ligature on both jaws, especially for undisciplined patients.

Usually, Hauptmeyer acid-resistant steel splints were applied and adjusted to fit the patient, either directly in his mouth or on a model set in the normal condition of occlusion. They turned out to be very comfortable, with their curved clasps for the application of elastic ligatures or bonds. Tooth fragments could be repositioned in their proper place by letting the attached elastic ligatures skip one or more of the steel clasps. We obtained good results by applying ligatures or intermaxillary bonding to reposition fragments which had only been slightly dislocated.

We had more complex immobilising appliances, cast silver splints with supports in the interdental spaces and hooks connected to elastics to dislodge fragments which had got wedged or stuck, effect the right occlusion and join the fragments together using a wire ligature. These appliances helped us to reposition the fragments in the more complicated cases. For a few patients we also used an inclined plane applied in the body of the mandible to reposition and occlude the fragments of broken teeth.

The most difficult cases requiring treatment in concentration camp conditions were mandibles broken in the edentulous part, along a line of fracture in the corner between the mandible and final tooth, especially in cases involving a challenging fracture line and loose fragments. We applied supports fixed on extended splints, but it did not always turn out to be a good and successful method; the fragments tended to be displaced, especially as they were under the impact of muscles pulling in various directions. The prisoners’ dental station in Auschwitz did not have a Roger Anderson pin fixation appliance, so all we could do to reposition and immobilise fragments was to apply splints and intermaxillary elastics.

In one case of a complex fracture in the edentulous part of the mandible with a torn mucous membrane, we put a brace on both the upper and lower jaw and repositioned the broken fragments in what seemed to be the best alignment, but no callus formation was observed. After we had successfully treated and removed the periapical abscess and sinus tract which had developed due to the infection of the fractured area, we decided to apply a bone suture made of a metal ligature to prevent pseudarthrosis. We sedated the patient with Evipan1 and made a lenticular section, removing the sinus tract right down to the bone and exposing the lower edges of the broken pieces of the mandible. We used a dental bur to make two incisions and applied ligatures to reposition the broken pieces. We then applied the layered closure technique to suture the soft tissue, leaving a elastic drain on the wound. The operation was followed by a severe inflammatory response lasting several days, but by the tenth day the patient’s condition had improved enough to have the drain removed and the small fistula it left healed completely within three weeks. A series of X rays confirmed bone regeneration and the growth of a scar. Unfortunately, our patient had spent two and a half months in hospital, and during the next selection the Lagerarzt sent him to the gas chamber.

All the care and hard work we had put in to treat this patient was wasted, and it wasn’t the only instance when this happened: there were many more paradoxes about Auschwitz. So many of our fellow inmates were sent to the gas chamber after being fitted out with a full set of dentures, having waited for months for a licence to come from Berlin allowing them to be given prosthetic treatment, only to be killed shortly afterwards. At one point, the staff of the prisoners’ dental surgery even started to have doubts whether there was any sense in providing prisoners with dentures, but eventually the opinion that it was our duty to help fellow inmates won the day.

Our dental surgery had a few serious cases of upper and lower jaw fractures following an Allied bombing raid which damaged the SS army barracks and one of the women’s prison buildings. The worst devastated were two SS workshop buildings in which prisoners worked. Most of the casualties reporting for medical treatment had been injured by debris falling from the devastated buildings.

One of the casualties had his mandible broken in two places as well as a broken shoulder blade and a splinter of wood lodged in the cornea of one of his eyes. We braced his upper and lower jaw and applied intermaxillary elastics before sending him to other specialists for further medical treatment. His physical condition was generally good, so his health problems were resolved fairly soon. The worst was the broken mandible; he was not a disciplined patient and kept removing his elastics to quickly eat the meals his mates from the workshop brought in for him. It was not until we explained all the details of the complications such behaviour could bring that he accepted and kept to our recommendations.

He was from Kraków and had all the qualifications allowing him to stay in the camp while evacuation was going on. Nonetheless, he asked the doctors to put him in the group of evacuees because he did not want to lose the chance to have specialist medical care. In the harsh conditions of evacuation and a short period of confinement in Mauthausen, he had little or no chance of medical care and treatment. After a few days, he was transferred to a small sub-camp, where he was left with no medical assistance at all. His elastics broke and he was left with just the splints, which he could not remove on his own and which were a risk to his life on a few occasions, as he told me later, because he was suspected by SS men of using them to smuggle gold in his mouth. When I saw and examined him for the first time after the war, he was in a fairly good condition. He had recovered, practically on his own, following the treatment he had received from us. His teeth and jaws were working quite well; there had been just a slight horizontal dislocation, and all he needed for full intercuspation was a bit of selective grinding on a couple of teeth.

We found that treatment of gunshot wounds and fractures was particularly difficult, but very few of these cases reached us because usually prisoners who were gunshot victims were killed off on the spot. Nonetheless, we did get two patients with such a condition.

One of them had a gunshot wound running from the left corner of the mandible to the right-hand side of the body. The bullet penetrated the soft tissue, injured the floor of the oral cavity, and stopped on the inner right-hand side of the mandible without fracturing the bone. The patient had a profuse sublingual haemorrhage, which suggested a damaged lingual artery. We decided to conduct surgery to remove the bullet and ligate the artery in the area of the Pirogov triangle. During the removal of the bullet and securing the wound, it turned out that the haemorrhage was from a branch of the lingual artery, not from its main part. We applied a ligature and sutures. There were no postoperative complications at all after the surgery.

The second gunshot case was for a wound in the area of the mental protuberance, which shattered the entire body of the mandible. The first procedure in the treatment was to brace the maxilla and mandible. We soldered inclined planes onto the splints and applied an elastic between the jaws to achieve normal occlusion in the premolar and molar area. We had a lot of problems with the front part of the mandible and were presented with a dilemma in the first phase of the treatment, whether to perform a sequestrotomy on all the fragments, or wait. We decided on the latter and waited for the necrotic fragments to fall out spontaneously, especially as some of them were still attached to the periosteum, which was damaged in parts.

In the first phase after surgery, when the epidermis and tongue was still very swollen and purulent, we administered the drugs we had available, Prontosil2 and a couple of intramuscular injections of Albucid.3 The patient was also given Pyramidon4 to bring down his temperature. We managed to control and remove the inflammation and purulence in a fairly short time, and the external wounds were healing at an exceptionally fast rate. The dressings we put on the chin area worked like a chin strap immobilising all the fragments and promoting the formation of bone scars.

The wounds were fully healed following the sequestrotomy of two small necrotic fragments of the crestal bone. Of course, we had to extract the teeth from this area in the first phase of treatment, because they were located along the line of the fracture and were fairly loose. The patient recovered quite quickly with an exceptionally good final outcome, despite the initial pessimistic prospects.

What was surprising about this fairly large number of broken crestal bones, maxillae and mandibles was the quite fast rate at which bone scars developed and the relatively low tendency of necrotic bone formation in patients who were concentration camp inmates and therefore very undernourished, debilitated and exhausted. Before a small unit for the treatment of broken jaws opened in the prisoners’ hospital, there was no chance at all for any sensible type of medical care for such patients, not least for the lack of peace and quiet to take their miserable meals slowly, what with block elders and room functionaries continually pestering them to hurry up. Conditions changed dramatically when we got the facilities to hospitalise such patients, who now had peace and quiet, a bed to themselves, and enough time to take their meals, now slightly better nutritionally than the run-of-the-mill food in the camp, at their own, slow pace. They also had a special diet, which has been described in an article by Julian Kiwała,5 and a regular supply of vitamins, “organised” unofficially in this difficult period by fellow prisoners Homme and Wesołowski, and later by Sikorski. These were the basic improvements.

Perhaps the chief reason for our patients’ surprisingly fast treatment and rate of recovery, and the good effects obtained, was their mental and psychological attitude. They enjoyed a sense of being given proper medical care, a friendly approach, and an atmosphere of peace and stability, all of which contributed to successful treatment, since few of our patients realised that the menacing chance of selection was still hanging over them.

I have no idea how many of our patients survived the camp. We lost contact with them as soon as they left the hospital, and had no chance of seeing them at all once the transports to other camps started and Auschwitz was evacuated. The last patients we had with jaw injuries was a group of Greek Jews; I don’t remember their surnames and camp numbers, just their first names, Salem, a senior academic from the University of Thessaloniki; Molho, an administrative clerk working in the port of Thessaloniki; and Halegna. It would be good to trace them to see the result of the dental treatment we gave them in such difficult and primitive conditions (especially as regards jaw injuries) and assess it in retrospect. The conditions in which we treated our patients can perhaps only be compared with the conditions on a battlefield during a war.

***

Translated from original article: Krzywicki, Janusz. “Obrażenia szczękowe w obozie oświęcimskim.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1967.

Notes

- Evipan (hexobarbitone)—a barbiturate produced by the Bayer pharmaceutical company and used as an anaesthetic. Clara Cotaru, “Evipan: The dark side of anaesthesia,”

https://www.geoffreykayemuseum.org.au/evipan-the-dark-side-of-anaesthesiaa - Prontosil, trade name of the first synthetic drug used in the treatment of general bacterial infections in humans. Introduced in the 1930s following research, directed by German chemist and pathologist Gerhard Domagk, on the antibacterial action of azo dyes. https://www.britannica.com/science/Prontosil.a

- Albucid (sodium sulphacetamide), a sulphonamide antibiotic now used as eye or ear drops. https://www.cheapmedicineshop.com/albucid-eye-drop-10ml-blephamide.htmla

- Pyramidon, Aminophenazone (aminopyrine, amidopyrine) a non-narcotic analgesic, first synthesized by Friedrich Stolz and Ludwig Knorr in the late 19th century, and sold as an anti-fever medicine known as Pyramidon by the German drug company Hoechst AG from 1897 until it was found to give rise to numerous dangerous or life-threatening side effects and banned in many countries. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aminophenazonea

- Kiwała, Julian. 1964. “Kuchnia dietetyczna (Dietküche) w szpitalu obozu koncentracyjnego Oświęcim—Brzezinka.” Przegląd Lekarski—Oświęcim. 80.b

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—note included in the Polish original version of the article.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

The contents of this site reflect the views held by the authors and do not constitute the official position of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.