Author

Tadeusz Bilikiewicz, MD, PhD, 1901-1980, psychiatrist, historian and philosopher of medicine, Professor of the Kraków Medical Academy, and Head of the Department and Clinic of Psychiatry at the Gdańsk Medical Academy.

We often hear the overhasty opinion that notorious perpetrators of genocide, capable of killing thousands or millions in cold blood, cannot be normal; they must surely be mentally ill. The average person – and “average people” make up most of the human population – just cannot understand how a sane individual could kill a human being. He could not kill a chicken or a fly himself. Nonetheless he is a meat eater and believes in pest control. Yet he does not slaughter animals himself. He lets a butcher do it for him. Some religions forbid their followers to kill animals and eat meat. Vegetarians observe these rules, too, either for ethical or hygienic reasons, or both. Killing people on any grounds at all is ruled out completely. Most people are filled with horror and contempt at the thought of cannibalism, even though cannibals do not consider themselves criminals, and they are not mentally ill, either. So there is a vast spectrum of ethical criteria we apply to evaluate the commandment “Thou shalt not kill.” Some people extend it to apply even to the creatures low on the ladder of evolution in the animal kingdom; while others turn a deaf ear even if it concerns millions of human beings. So let us take a closer look at this issue.

The disputes on whether we have inherent ethical principles subsided a long time ago. We are born with an innate superior emotionality in the sense that as our personality develops we have a tendency to cultivate superior emotions, and this applies to our sense of ethics as well. The environment in which we are brought up and educated instils the superior emotions in the disposition we are born with and are capable of developing. The inherent roots of our emotionality may be prevented from growing due to a pathology, or they may be stopped or corrupted as our personality develops. But here I am going to consider the wholesome growth of those inborn roots and the healthy development of the individual’s psycho-physiological constitution. For the time being, we will put aside characteropathic disturbances of the superior emotions.

A normal person, who has been developing since childhood in the right conditions, by which I mean not subject to any pathogenic factors, considers a thing right or wrong in accordance with what his educators (in the broad sense of the term) have taught him and continue to teach him. Individuals and large groups tend to be highly uncritical in this respect, and the extent of their lack of criticism is evidenced by the relativism of our ethical principles. A set of ethical principles which is binding on cultivated people has evolved over the centuries, and children and young people have been brought up and educated in accordance with these principles. A cultivated person considers homicide unethical and criminal, even though every child knows that the legislators and moralists of many cultural nations actively or tacitly permit numerous exceptions to the categorical rule of “Thou shalt not kill.” Some of the exceptions tolerated are, for instance, capital punishment and war. Radicals call for the abolition of the death sentence and protest against war, sometimes even defensive war. Such radical opinions come from the fear that the range in which capital punishment is applicable and the extent of armed warfare may be stretched out to infinity.

We may derive a few reflections from the fact that cultural countries tolerate exceptions to the rule of “Thou shalt not kill.” An honest citizen who is called up for military service considers himself exempted from this rule. On the contrary, if he is engaged in killing in the course of a war, he is regarded to have “done his duty honourably.” He is censured and punished if he avoids killing. During a war people’s consciences and sense of ethics fall silent. A judge who hands down a death sentence and the hangman who carries it out have a clean conscience. A soldier who kills to obey an order has a clean conscience, too. The number of those sentenced to death or enemies killed does not matter at all, there may be hundreds of them, thousands, or millions. The mass scale on which such killings are done legally does not affect the conscience of the killers, who act on orders of a legal authority and in compliance with the law. So the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” is not a categorical imperative if in exceptional situations people’s conscience is mute, and the sense of ethics of healthy and honest citizens tells them to do the opposite: “Thou shalt kill.”

What and who determines whether one and the same act is regarded on one occasion as a crime, and as a merit on another? In the philosophy of law, there have been many discussions on the origin of authority. It would be a good thing to have a supernatural authority give the human race a categorical list of laws to observe, and see that they were kept by directly intervening in our doings. We would have governments that were perfect, and life would be paradise. But we do not, alas. In reality, what makes the world the way it is, is the resultant of humanity’s collective egoisms. Overcoming those human egoisms will depend on us humans, and with time we will certainly create an order approaching a paradisiac utopia, but for the time being the world is the very opposite of paradise, its negation. In the most elementary human community, the family, it is the parents who are, or at least should be, the lawgivers. But they, too, have to keep to the laws instilled in them by their upbringing. The purpose of these laws is to control the individual’s egoism, but they, in turn, are subject to collective egoism, which again has to be kept in order by a superior social order. For a strong state authority aware of its purpose, controlling the collective egoism of individual social groups is a matter of efficient organisation. However, despite numerous efforts, we have not yet managed to set up such an authority to control egoism at the level of the state.

Interpersonal relations may be under the rule of the strongest, the rule of the fist, under jungle law. In such conditions, the strong man violates the rights of the weaker, robs and kills them, rules by terror. The motive for such behaviour is extreme human egoism. If people who share this mentality club together in a gang, it is the gang’s collective egoism that imposes the principles of its ethics on its members and subordinates. If it is a gang of thieves, then murder for the sake of robbery and participation in it turn into the duty of all the members of the gang. If the gang brings up its children in this spirit, their ethical principles will be nothing like the ethical principles of the society which the gang has left. The young people in the gang will look up to a negative character and emulate him. A youngster in the gang who has been brought up by his family to observe different, old-fashioned ethical principles will find himself bound in his conscience to follow the “Thou shalt not kill” commandment. If ever since the start of his personal life he has been taught a different set of superior emotions, he will probably be ashamed that he is not like the negative character who is his leader. From a certain point of view, the gang’s ethical principles are “grand”: fellowship, professional confidentiality, solidarity and readiness to sacrifice one’s life for one’s fellows, even unto the point of death. The things members of the gang regard as ethical vices are insubordination, cowardice, selfish behaviour running counter to the collective egoism, effeminacy and softness as regards carrying out cruel orders, treachery, informing on the gang etc. Their most noble feelings have been subordinated to the interests of the gang. A singular set of ethical principles stands on guard of these interests and aims, disciplining the gang’s members to see that the rules are rigorously implemented. Discipline tends to be a remarkably successful tool because it works on the basis of conditioned reflex reactions. After just a short time in the service of the gang, the categorical imperatives instilled in gang members during their childhood attenuate and vanish. If need be, for the sake of the gang they are ready to kill.

Propaganda is the most powerful instrument of education. We know its power well. It makes whole nations believe a lie or not believe the truth. Our generation has witnessed the most extraordinary events which have occurred on a mass scale in this connection. Already before the war, Hitler’s deceitful Nazi propaganda was persuading Germans that the most savage oppressive measures were being applied against the minorities in Poland, and this was going on precisely at the time when the concentration camps were already operating in Germany and the methods of extermination were on the rise. To justify military aggression to the people, Hitler had to resort to propaganda to present the offensive war as Abwehr durch Angriff (defence by means of attack). The German people have never been any more credulous than any other nation. The secret behind the success of this defamatory propaganda was that the people who gained power in Germany had no qualms about the measures they employed. Cowardly themselves, they gave the orders for and saw to the execution of the genocide. They also had a personal interest in organising a cover-up. There was never a law on euthanasia in Germany, but pseudo-euthanasia was a reality, meticulously hidden under a smokescreen of orders which spoke of resettlement, a final solution, isolating off, emigration etc. None of those in the know ever believed in all these false appearances, if only for the fact that talking about it was prohibited. Radio and the press, as well as all the other tools of propaganda applied to educate the masses, were in the hands of the ruling oligarchy. Intelligent people could deduce the terrible truth, but since all criticism whatsoever was banned, and in fact absolutely impossible under the reign of terror, no one voiced a protest. Still less likely was the emergence of daredevils ready to defy the mass atrocity by deed. The idea and attempt to carry out a coup did not emerge until it was all about to collapse anyway, and the days of tyranny were numbered.

Of course, the reign of terror can explain a lot. But not everything. Apart from the demoralised, terrorised, and overwhelmed part of German society, there was also a large part of it which remained decent and intellectually independent. There were also millions of German émigrés, who did not fall for the lies or succumb to the terror. How was it possible that the decent part of the German nation did not embark on a large-scale campaign of protest and information? Why did the honest people keep their mouths shut and remain silent about the truth of the death camps, the extermination of millions of Jews, the methodical violation of international law, of the Hague Convention, and of human rights?

The secret of this conspiracy of silence may lie in the effectiveness of the propaganda methods. Chauvinist ideas had deep roots in German society, going back many centuries. For centuries the masses had been brought up to believe in a German cultural mission. The average intelligent German thought of the Drang nach Osten (Eastward Thrust) as the materialisation of the sacred cultural mission to be carried out by the German nation. The real nature of the Teutonic Knights’ expansion into the Easta was colonising and imperialistic, only hidden under the mask of a religious mission. To achieve this aim, the Teutonic Knights had to convince their own nation that the peoples living in the East were backward and barbaric, and that it would be beneficial, salutary, and felicitous for them to be converted to Christianity. Their lofty, sacred slogans and an outer show of the Cross were coupled with conversion by fire and sword, violence, robbery, and slavery. We could even address the question to that distant age – did the decent and fair part of the German nation of those times offer any opposition whatsoever to that invasive expansion, to the cruelty and deceit? They were different times, and the methods of bringing up the masses were different, nonetheless, the appeal was made to the lowest, power-loving instincts in the German masses, and it fell on fertile ground. The cruel ideology of the Nibelung and Grimm’s fairy tales had been moulding the mentality of the German people since their childhood. The triumph of brute force and contempt for weakness. “Der Herrgott ist immer mit den stärksten Kanonen,” [The Lord God is always on the side of the mightiest cannon] said Frederick the Great. Hegel’s objective spirit and the German State were identical. Providence was watching over the German Nation and State. Under the German Empire and in Hitler’s times, the German masses were nurtured on the vision of a Great Germany, whose divine destiny it was to rule over the nations of the East and over the whole world. They all knew that there was no other way to put this grand imperialistic intent into practice but by military means. There was no other way to conquer the world. Every German had to devote all his powers to these grand aims. The propaganda which had been conducted for centuries proved effective. For centuries a patriotic national pride had been established and swelled up vastly in German minds, along with a haughty ambition to rule over vanquished nations, whose racial inferiority was due to the will of Providence that favoured its chosen nation.

There is only a quantitative difference between a moderate effort to expand the borders of one’s country and a drive to conquer the whole world. There is only a quantitative difference between chivalric combat and total war. And only a quantitative difference may be observed between an armed robbery by a gang of thieves and the Nazi German invasion of a country which had no Quisling. There is only a quantitative difference between an individual murder and robbery and the mass killings and robberies perpetrated in the Nazi German concentration camps. Whoever condones a duel as a method to resolve a dispute must also condone warfare of all manner and magnitude, right up to a thermonuclear war. Whoever teaches children and young people that the law of the fist is admissible as a method to resolve conflict is thereby a teacher sowing the seeds of a future war. Since the very beginning of human history there have always been wars. But human history has also recorded numerous impressive examples of good neighbourly relations between nations and countries. The inclination to make war and the drive to gain power are inherent in the human psyche, yet their growth is the outcome of nurture and education. Individuals and nations may be educated to love peace and justice, but they may also be educated to cherish the practice of war and plunder. It is possible to inculcate in the minds of children and young people the opinion that only the strong have the right to live, and that the weak may stay alive only if they agree to be slaves. If not, they must die to make room for the strong, who have the right to any means and measures, even the cruellest and most brutal, to achieve their selfish aims.

There is also an evident hierarchical range of methods to choose from for the achievement of such egoistic purposes, from the gentlest to the most savage means. The indiscriminate slaughter of vanquished enemies, maiming and torturing them, or castrating them to turn them into obedient slaves, have been around since the most ancient times. Sometimes, in a fit of pride, we boast of the achievements of the 20th-century culture and we fancy that the past centuries were full of obscurity and barbarity. Our pride is unfounded. We do have the right to be proud of the progress we have made in civilisation, but at the same time we must not turn a blind eye to the fact of history that along with the advancement of science and technology there has been a rise in the intensity of savagery and in the efficiency of the methods of destruction. Genghis Khan murdered only five million; Himmler murdered far more. None of the previous wars cost so many human lives as the Second World War. From the caveman’s cudgel to the hydrogen bomb – that is the path of development human culture has taken. Maybe sometime in the future the world record will be beaten. Right now the record holder is still the empire under the sign of the swastika.

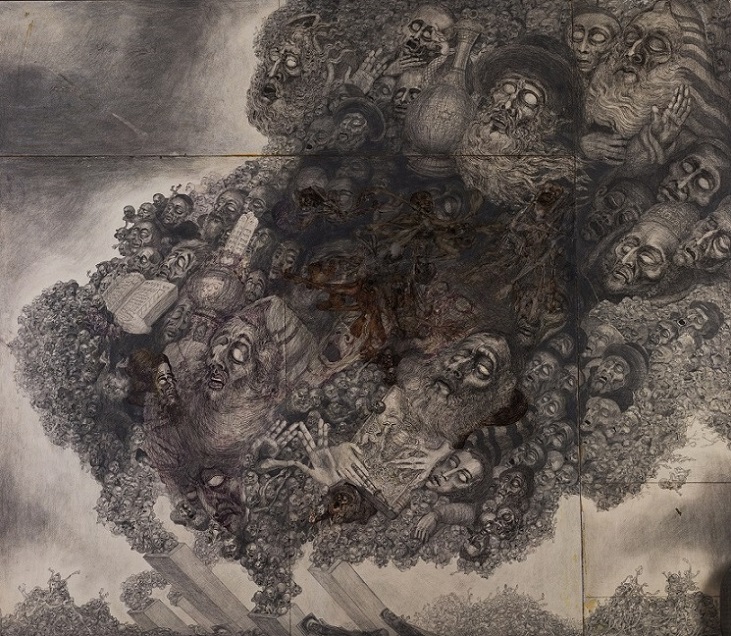

The Chimneys (Smoke over Birkenau). Marian Kołodziej

In every nation there are, there may be, or even must be criminals, apparently. This is due not only to social demoralisation, which may occur in any community, but it also comes about as a result of the characteropathic attributes of some individuals with an organically damaged central nervous system, who are, therefore, particularly susceptible to develop a secondary sociopathic personality and initiate criminal activity. Yet everywhere, in all the cultural countries, public opinion representing the decent majority stands on guard of collective ethics to prevent lawbreaking and to firmly condemn the violation of human rights. In our own times, too, not so long ago, there were instances of abuse which could even have led to genocidal practices, had it not been for resolute opposition from the decent part of society. We are not proud of Bereza Kartuskab the period between the World Wars, but we have the right to assert that this germ of a concentration camp immediately came up against vociferous protest from the decent part of Polish society. There have also been instances of abuse of the law in the post-war period but they were firmly and thoroughly brought to a stop in the “October period.”c Was German society able to make such a firm stand, and protest and condemn the genocidal projects and practices, either before, during, or after the war?

I have recently published reviews in Biuletyn Głównej Bibioteki Lekarskiej and Neurologia, Neorochirurgia i Psychiatria Polskad on two books I consider the most important contributions to the work on the genocide perpetrated by the Nazi Germans, published almost at the same time in 1964. One is by a Jewish survivor, and the other by a group of German authors. What a tremendous difference in the treatment of the same subject! What a different picture of the same facts, through the eyes of a victim, and by members of the nation which through the spokesmen of its new spiritual leaders should be disavowing the monstrous genocide and doing all it can to remedy the wrongs it caused, expunge its disgrace, and stop the Nazi hydra from sprouting new heads in the future.

Leo Eitinger, the author of the first book, originally from Czechoslovakia, graduated from Brno University in 1937. The Second World War forced him to flee to Norway, where the Nazi Germans detained him because he was Jewish and sent him to Auschwitz. He was one of the very few Jews to survive. His book is based not only on his own recollections of the hell of the concentration camp, but mostly on his research on the survivors of the Nazi German atrocities who settled in Norway and Israel after the war. In 1958 he received a doctor’s degree on the grounds of a dissertation on the refugees in Norway. His present book is the result of more research on the subject. He travelled to several countries to collect his research material, and spent a whole year researching in Israel on the invitation of the Israeli government. The renowned Norwegian psychiatrist, Professor G. Langfeldt, was his boss. Currently, Dr Eitinger is head of the Psychiatric Clinic of the University Hospital in Oslo.

Eitinger’s book is very well written. It deserves commendation above all for its scientific documentation and for the objectivity with which it has been written. As it is in English and is being distributed by the well-known publishers Allen & Unwin, readers from all over the world will be able to learn from a direct source about the truth of the Nazi German concentration camps. There are certain groups which have been trying for a long time to cover up or even misrepresent the truth about the monstrous slaughter of millions of defenceless people, distorting it to suit the hostile German propaganda. Not only in Germany, but all over the world there are still those who do not want to know that terrible truth.

Eitinger’s bibliography covers seven pages. He has issued seven scholarly publications on Nazi German oppression himself. His scientific materials are divided into chapters as follows. After a short introduction, he presents the general political background which eventually led to the extermination of entire “racially alien” groups, with an account of the methods applied for the extermination and the moral and physical ordeal of the victims. He discusses the literature of the subject in detail and compares it with his personal experience and his own and other writers’ research results. He gives separate descriptions of the Norwegian and Israeli groups and presents case histories with points such as the subjects’ condition prior to imprisonment, their family life, school-days, age, marital status, and personality traits, all of which he gives in meticulously drafted statistical tables and data. Next, he reconstructs his subjects’ somatic and mental condition during the period of oppression and concentration camp imprisonment, and after liberation. This methodology allows him to determine the nature of the personality changes in victims which helped them survive, their condition on liberation, and what they are like now as regards employability, their present mental and somatic condition, and the disorders they are suffering from. On the basis of his clinical observations, he goes on to give a general definition of the concentration camp syndrome, the most frequent symptom of which is chronic reactive depression. Not all of his subjects developed the same psychiatric conditions. He could observe clinical symptoms of psychosis which were different for the Norwegian group and for the Jewish group, different for the neurotic subjects from those observed in survivors in regular employment. Predictably, he observed the severest consequences in the Jewish subjects, for whom the Nazi Germans had set up the cruellest conditions in the concentration camps. As regards the level of severity, the fate of the Poles and Soviet prisoners-of-war in the camp was not much better. The Norwegians were one of the “privileged” groups, which does not at all mean that large numbers of its members did not die or suffer physically and morally. Eitinger’s book is an exemplar of objectivity and free of emotionality, which would have been understandable in a victim of the most dreadful oppression. There is no hint of vindictiveness in what Eitinger writes, and this is without doubt one of the features enhancing his book.

Let us now take a look at the publication compiled by the German authors, which, in a way, we could regard as representative or typical. At any rate, the nearer we got to 1965, the time bar in the West German statute of limitations on Nazi war crimes, the more we got in the way of serious publications in West Germany on the effects of Nazi German crimes. All we can speak of now are the very distant effects, as only a few of the survivors are still alive. The book by Baeyer, Häfner, and Kisker is by no means on all of the victims of Nazism. These and other German authors are only interested in individuals who have the right to claim compensation, in other words, are entschädigungsberechtigt under the West German law. The West German compensation act did not come into force until 1956, over a decade after the war finished. The regulations formerly used in the jurisdiction could not be applied to determine the pathogenesis and extent of the injuries claimants had sustained due to the satanic oppression they had endured on a mass scale, and new criteria and standards had to be brought in. This was the aim of these authors, who collected up the records of West German court decisions on compensation claims brought by victims of Nazism and the psychiatric diagnoses relating to such cases.

The book was written at the Psychiatric and Neurological Clinic of Heidelberg University. Its chief author, Professor Baeyer, is head of the Clinic, and Drs Häfner and Kisker are his adjunct staff. They have used a set of 700 diagnoses they have issued themselves for compensation claims. Their research covers the past eight years. The majority of these 700 claimants – 398 individuals – could not be examined in person because they had died or were otherwise inaccessible. Moreover, the data pertaining to only 535 claimants were available for statistical analysis. As a result, the authors could examine and carry out clinical observations on only 137 of these victims, without having to rely merely on documents, information provided by the claimants themselves, and earlier rulings on their cases. This reduction in the number of subjects examined quite naturally diminishes the value of the study. The authors are candid about the fact that they have studied only a minute fraction of the countless masses of victims of the Nazi reign of terror, now scattered all over the world. Remarkably, they considered only the literature of the subject and the material relating to individuals from German-, Danish-, Norwegian-, French-, English-, and Dutch-speaking regions, as if victims from parts of the world not speaking these languages were still Untermenschen whose fate did not deserve to be considered. Explaining this away with the linguistic problems involved in referring to foreign-language publications would sound pathetic in this day and age, what with the current availability of translation services, or even simultaneous interpreting. Perhaps we ourselves are to blame for the fact that our countrymen have been passed over in the compensation claims.

At any rate, it would be fair to say that the value of retrospective research of this kind would be infinitely greater 1) if the Germans had carried it out straight after the war, when there were still many victims alive and when the memory of the hell they went through was fresh; 2) if the all-too-well-known German tendency to cover up, obscure, and diminish the enormity of the Nazi crimes had been stopped in all fairness; and 3) if the study had covered all the regions of the different languages spoken by victims, in other words, if it covered all the victims of the terror. It has been a grave mistake to make distinctions among the victims. Some were accorded the right to claim on the grounds of their domicile, citizenship, their technical accessibility to claiming their rights, and other conditions and reasons. The West German government, which considers itself the legal successor to Hitler’s state, should have made an official declaration worldwide condemning Hitler’s policy of extermination, disavowing the slogans, aims, and methods used by its predecessor, fully acknowledging the moral and material damage, and the harm to the health of individuals and entire societies, and announcing that it wanted to do all it could to redress the wrongs, diminish the suffering, and provide material compensation regardless of costs. If it had issued such a statement, all the victims from all over the world would have responded. The clinicians and theoreticians would have had a pool of millions of direct or indirect victims as subjects for their research. The scientific value of a project of psychiatric examinations carried out on such a mass scale and straight after the event would have been colossal. If the Germans had demonstrated their good will in this way, they would have done a lot to deflate the bitterness and sense of injustice which people of the countries most oppressed by German occupation still feel. If they had behaved in this way, the successors to the Third Reich would have saved themselves from the charge of sympathising with the war criminals. And we would not have had the embarrassing post-war discoveries of war criminals in senior offices or management in the German Federal Republic. The war criminals would have been denounced and debarred from participation in community affairs with the decent part of German society.

Now we can compare Eitinger’s book with the work of Baeyer, Häfner, and Kisker. What a different methodology for the collection of case studies on particular individuals for study! The German authors restricted their work to the examination of the cases of individuals who lodged a compensation claim in a German court. Eitinger did not wait for the victims to come to him, but searched for them and went to them himself. Of the numerous trips he made to many countries, he spent the longest time in Israel, a whole year, with the help of the Israeli authorities resolutely trying to trace survivors of the Nazi reign of terror. And he did trace them. But we may say that his motives were different. He was not just an academic dispassionately observing the predicament of the victims of years of the cruellest tortures you could imagine; he was also their companion and fellow-sufferer of their ordeal, who understood its effects because he had experienced them himself. We have to admire Eitinger for having written his book with the thorough objectivity of a scientist, without a trace of vengefulness or hatred. The objectivity of the German authors is different – unemotional, to the point, cool, and notwithstanding the words of condemnation for the Nazi past – haughty. If these authors had come to Poland, for instance, and talked person-to-person with the orphans who have been left for the rest of their lives with the memory of watching their parents being tortured by the Gestapo, perhaps they would have climbed down from their high horse, discarded the insensitive approach of their forensic psychiatric expertise, and come to appreciate the permanent consequences in the personality of an individual who has not been tortured physically, yet has certainly been injured, even though he may not have any neurological or psychiatric symptoms to show for it. Perhaps if they had been shocked by the enormity of the human tragedy, they would have extended the bounds of their study far beyond their selected human material of those who on the grounds of the 1956 compensation act, many years after the war and wartime occupation, qualified as entschädigungsberechtigt.

From the point of view of the method and structure, Baeyer, Häfner, and Kisker’s book is unfaultable. They have sub-divided it into a general part and a clinical part. In the general part, they describe and analyse the Nazi reign of terror against a background of remarks on the sociology of terror in general. They give a vivid picture of the concept of racial discrimination and describe the anti-Jewish operation carried out in the autumn of 1938. They examine the idea of the “Endlösung (Final Solution) to the Jewish problem,” and they provide the reader with information on the different types of concentration camps and the ways in which prisoners adjusted to life in them; finally, they describe the way people vegetated in the ghettos and the dreadful conditions they were forced to live in, or to seek shelter in hideouts, before they eventually died. Next, the authors discuss the psychopathology of the greatest possible stress situations and their immediate and distant effects. To conclude this part of the book, they provide a transcript from the legislation on the grounds for claims victims may bring for what they have suffered.

The clinical part of Baeyer, Häfner, and Kisker’s book is exemplary. It has been sub-divided into sections on the diverse tests, followed by the various psychopathological syndromes, separately for the vast group of reactive conditions and for the psychoses. While there were no major problems with the section on reactive conditions, a number of difficulties emerged with the psychoses. There were misunderstandings relating to the discrepancies in the diagnostic terminology used by German psychiatrists and their counterparts from the English-speaking countries. Another problem arose over the endogenous psychoses, where it was difficult to determine beyond all reasonable doubt whether they would have developed in the subjects irrespectively of their ordeal. There were difficulties with these patients’ hitherto unexplained aetiology and pathogenesis of the endogenous psychoses, bouts of which sometimes occur due to a different, not necessarily specific cause. On the whole, decisions on compensation claims were made on the basis of pragmatic criteria, though in many cases the grounds for the decision were founded on probability rather than absolute certainty. There were also difficulties with the insistent way in which some applicants pressed their claim, but an attitude of tolerance was adopted to such conduct. This part of the book ends with a recapitulation of the principles governing the jurisdiction for compensation claims, though of course, the reader can gather information on this in the course of reading the book. There are numerous case studies. Reading the book is a tense experience as if it were written by a gloomy novelist fond of the macabre. Yet these facts are more sinister than fiction – a tragic product of the 20th-century culture. Besides, from the land of Goethe and Schiller! From the land of Immanuel Kant, whose philosophy of categorical imperatives would have denounced transgressions infinitely less serious than the crime of genocide.

How are we to explain the harmonious coexistence of opinions which are so diametrically opposed to each other in one and the same nation? Why is it that a quarter of a century after these atrocities the entire cultural world still has to fight to prevent the imposition of any kind of limitation on the prosecution of genocide? Why are courts in the German Federal Republic acquitting nurses who killed defenceless children in mental hospitals? Why are they handing down such ridiculously light sentences on mass murderers that one can hardly refrain from considering them indulgent? How can we explain the fact that everywhere except in West Germany people are appalled by the genocide? Why is it that judges and prosecutors who are not German are far more stringent than German judges and prosecutors? How can we explain the fact that in the German Federal Republic war criminals have been living for years in the midst of German society, treated by decent Germans as respectable fellow citizens, people they are on friendly, hand-shake terms with and certainly not looked down on with contempt? Why has the role and purpose of public opinion faded away in that country?

There is a general answer which inexorably comes to mind to that question: presumably, most of the people of West Germany do not consider genocide a crime. Presumably, the idea of total war has gone down so deeply into their psychology that they regard it as a sort of national duty. They do not blame their soldiers for having committed mass murder during the war; neither do they blame the perpetrators of genocide for having obeyed orders from their superiors during total war and killed foreign peoples officially recognised as enemies of the German nation, and therefore dangerous and harmful, to be eradicated in the interest of the German nation. The people the Nazi German authorities employed to carry out the killings were not just criminals and psychopaths. They also sent in cultivated individuals, whom they persuaded that total war was the right and necessary thing to do. Their air raids on open cities, targeted against defenceless people, against women and children, were also genocidal in character. The Luftwaffe did it on orders from their superiors.

The arguments for the defence of the war criminals are as follows: the SS butchers in the concentration camps were soldiers obeying orders. They killed because they had orders to kill. Just like soldiers, they were duty-bound to obey orders blindly. In a total war, you have to kill enemies on the home front. War was waged not against enemy military units, but against entire peoples. Those who kill enemies on a mass scale on an external front using modern weapons are dubbed heroes. They are treated with respect and honoured for what they have done for their nation, even though they are homicides. The same honour is due to those killers who committed murder on orders from their leaders for the sake of their nation, slaughtering whole nations which the Nazi German authorities had sentenced to death. This kind of reasoning exonerates the war criminals from all the blame. In fact, Hitler, Himmler, Goering, and Goebbels took all the blame upon themselves, and the others were only carrying out Hitler’s orders. Their subordinates, in turn, were carrying out their orders, passing them down to subordinates lower down the ladder of command. The gigantic machine which worked on a system of military discipline and had fantastic propaganda resources at its disposal fanaticised and blinded the German masses, winning over even the decent Germans who acted on a patriotic impulse, convinced that they were on a holy war for the wellbeing and security of Great Germany.

Brought up on the standards of anti-totalitarian ethics, we are still applying the normal gauge to evaluate the deeds of Nazi German criminals. Our standards seem alien to people who have been brought up since childhood in the spirit of total militarism. Such people do not censure war, whatever form it might take. The bloodied hands of heroes of the swastika do not appal them. For them, they are just ordinary people who follow an ethical code different from ours. Their principles are in harmony and concord with their superior emotions. I remember how the SS-men employed to kill the mental patients of Kocborowo hospitale spent their leisure time. After they had heroically carried out their duty and returned to their quarters on completing their bloody job, they would gather in a mess-room arranged on the first floor of the hospital’s administrative building. One of them was a talented violinist, and another played the piano. You could hear music and singing coming from the windows of the mess-room. The terrorised Polish inhabitants, who were being systematically decimated, trembled in defenceless terror, while those Germans indulged their artistic inclinations, loftily and nobly, as befits fine, sensitive spirits. A cutthroat’s bloodstained hand fondly drew the bow over the strings of his violin. The others listened enraptured and dreaming of their great Vaterland, which they missed so terribly, serving it faithfully and with the utmost devotion.

Translated from the original article: Bilikiewicz T.: Z rozważań nad psychologią ludobójstwa. Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim, 1966.

Notes:

a. The Order of the Teutonic Knights, a medieval German crusading order which colonized the Baltic coast area which much later served as the foundation for East Prussia, “converting” (or in fact exterminating) indigenous pagan peoples.

b. Bereza Kartuska - an internment camp where the Polish government detained political prisoners, in operation 1934-1939.

c. The post-war period - viz. Stalinism; this text was written after the political thaw of 1956 in the Communist countries, which denounced the earlier period under the rule of Stalin, but remained silent about the later abuses under the Communist regimes.

d. Polish medical journals.

e. Kocborowo – a large mental hospital near the city of Starogard (northern Poland). In 1939 and 1940 the Germans took the hospital’s patients to a nearby wood and murdered them.

References

1.Eitinger, L. 1964. Concentration Camp Survivors in Norway and Israel. The Norwegian Research Council for Science and Humanities, Sektion: Medicine E. 305. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.2.Baeyer, W., Häfner, H., and Kisker, K.-P. 1964. Psychiatrie der Verfolgten. Psychopathologische und gut-achtliche Erfahrungen an Opfern der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung und vergleichbarer Extrembelastungen. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.