Author

Stanisław Kłodzinski, MD, 1918–1990, lung specialist, Department of Pneumology, Academy of Medicine in Kraków. Co-editor of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Former prisoner of the Auschwitz‑Birkenau concentration camp, prisoner No. 20019. Wikipedia article in English

Many a time the persistent and often victorious struggle of doctors arrested and incarcerated in the German prisons and concentration camps transcended the prison walls or the barbed wire of their confinement. Their aim was not only to save their companions’ lives, but also, for instance, to frustrate the Nazi German criminal pseudoscientific research, in situations like the production of drugs or vaccines.

Prisoner-doctors conducted this struggle under constant threat of losing their own lives, and all methods were considered good if they achieved the intended aim. Usually they departed a great deal from the rules these doctors had been taught during their medical studies. Polish prisoners played a significant role in this battle. Thanks to their knowledge, dexterity and skills, they usually held important jobs in the concentration camp sick bays, hospital blocks or SS medical institutes. This was so both in the Pawiak and Montelupich prisons, and in the concentration camps Stutthof, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Gross-Rosen, Majdanek, Mauthausen-Gusen, Ravensbrück, Neuengamme, Dachau, Buchenwald. The activities of prisoner doctors, many of them forgotten and their work not researched, deserve to be made public. For example, the general public does not know much about the activity of Marian Ciepielowski, a prisoner doctor at Buchenwald, who died a few years ago.

In August 1943 Sturmbannführer Dr Erwin Ding-Schuler, an SS doctor, set up a typhus fever and virus research department in Block 50 at Buchenwald near Weimar. In this block vaccines were to be produced against typhus fever using Professor Giroud’s method on the lungs of mice and rabbits. Dr Ludwik Fleck, a docent from Professor Weigl’s1 Institute in Lwów,2 was brought over to Buchenwald via Auschwitz and imprisoned in the camp. In addition, the best specialist doctors, bacteriologists, serologists, and chemists were sent to Buchenwald and allocated to a special medical commando, which included Prof. Balachowski from the Pasteur Institute in Paris; the Czech bacteriologist Dr Karel Makovicka; Kolosov, a Russian bacteriologist; Prof. Suard, a French pharmacologist; Prof. Kirmann, a chemist, and Dr Robert Waitz, an internist, both from the University of Strasbourg; the Dutch physicist Prof. van Lingen; Jean Robert, the Dutch national consultant for physical education; the architect Harry Pieck; the distinguished Austrian journalist Eugen Kogon, who was later appointed to a professorship; and several others.

A total of 65 prisoners including 12 Russians worked there. Seven Jewish colleagues were sent to work there as well, which saved them from certain death. Dr Ding-Schuler, a fanatical Nazi and anti-Semite, must have considered this commando the ultimum refugium Judeorum (ultimate haven for Jews who were still alive). Marian Ciepielowski, a Polish prisoner-doctor, was appointed production manager.

The equipment for the workshop came from France; it was either looted or “redeemed” without subsequent payment. As Eugen Kogon writes in Der SS-Staat. Das System der deutschen Konzentrationslager, Block 50 was a true haven in the camp. The prisoners working there, albeit exposed to laboratory infection and subject to the authority of a difficult boss, had relatively good living conditions right until Buchenwald was closed down. They all had a bed to themselves, a “luxury” which most concentration camp inmates never dreamed of, fresh bed linen, light and clean workrooms. Furthermore, since prisoners working there were at risk of infection, they received a weekly extra in the form of 80 grams of sugar, 64 grams of fat and 400 grams of bread. To top it all, they had the infected rabbit meat, which they first heated up to 120 degrees Celsius, cooked, and then ate, illegally because once the lungs needed for production had been removed it should have been incinerated. Block 50 residents were exempted from the camp’s exhausting roll calls. Buchenwald’s SS-men feared and respected this commando and the commando from Block 46; and both Sturmbannführer SS Dr Ding-Schuler and the prisoners created an atmosphere of fear and a no-go precinct by putting up noticeboards with warnings and an additional barbed wire fence around the barrack.

According to Eugen Kogon, the strains of Rickettsia provazekii bacteria were bred from 2 cu. cm of blood drawn from each patient in Block 46 and transfused into guinea pigs. Officially two types of vaccines were made: the normal vaccine designated for SS combat units, and a somewhat murky spin-off substance for prisoners. In fact, the “vaccine” prepared in large quantities for the SS was medically useless, albeit harmless. But the murky “offshoot” was the effective product, and successfully distributed to prisoners at risk of typhus fever.

In a letter written on 31 January 1947 to his family, prisoner Marian Ciepielowski, the production manager, gives a clear and straightforward description of this sabotage:

The sabotage consisted in the fact that instead of the vaccine we were supposed to produce from mouse and rabbit lungs according to the new method designed by Prof. Giroud,3 we produced 600 litres of water slightly stained with blood and seasoned with formalin for the SS combat units, while 7 litres of the real vaccine of our own production, which turned out to be better than Weigel’s, was used to vaccinate ourselves and other Buchenwald prisoners. Moreover, in just under two years we ate over 9 thousand rabbits, and utilised thousands of white mice and guinea pigs.

In 1947 Klemens Barbarski wrote the following in an article on the subject in the Polish magazine Przekrój:

[T]he Buchenwald scientists modified the Giroud production method. They used guinea pig brains, instead of infected lice, as in the Giroud method. The supervisor of the Buchenwald SS Institute was Dr Ding-Schuler, an SS doctor who let them introduce this modification, because first he was not an expert himself, and secondly he did not want lice to be brought into the camp.

Everything seemed to be going smoothly and vaccine production started. A total of 600 litres was produced, which was administered to about 30 thousand SS men fighting on the front. The production was going well, the SS doctors were pleased with the Institute, and even the majority of prisoners working there did not suspect anything, when suddenly trouble struck like a bolt out of the blue. Dr Ding-Schuler was presented with the work of a Romanian scholar, Prof. Combiescu, on the production of anti-typhus vaccine. That scientist showed that you could not run an intestinal transit experiment on rabbits and mice if you started with the brain of an infected guinea pig.

Ding-Schuler smelled a rat (pardon the pun), and the prospect was the gallows for all the prisoners working in the hygiene institute. And then the group of scientists in the know ventured on an even bigger gamble. As if butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth, Dr Ciepielowski told the SS doctor that the Romanian scholar was wrong and that he (Ciepielowski) would write a paper proving that you could produce a vaccine, even a good-quality one, using the Buchenwald method. Ding-Schuler consented to this, and as no prisoner was permitted to publish under his own name, Ding-Schuler put his name on the article written by Ciepielowski, sent it to the scholarly journal Zeitschrift für Hygiene Instytut und Infektionskrankheiten, which published it in its July 1944 edition.

Dr Eugen Kogon also adds that

. . . in the last two years of my work as a clerk to the SS doctor of Block 50, Dr Ciepielowski and I wrote half a dozen professional medical contributions on the subject of typhus fever, inspired by our dangerously sarcastic attitude to Nazi science. Dr Ding-Schuler published them under his name in Zeitschrift für Infektions-krankheiten, Zeitschrift für Hygiene and other scientific journals. Ding-Schuler’s personal contribution was handling the statistical data we gave him, which was all bogus. In a report about droplet infection in typhus fever, he expressed his reservations by claiming that 10 thousand smears had been made without finding even a single Rickettsia prowazekii. We used to test just one sample, and all the other ones were ignored.

Incidentally, in his capacity as Ding-Schuler’s clerk, Eugen Kogon took care of most of the Sturmbannführer’s correspondence, including his love letters and his condolence letters.

During the Nuremberg trials the activity of Dr Ciepielowski in Buchenwald was mentioned several times, and Dr Eugen Kogon’s testimony in both the Nazi Doctors’ Trial and his book Der SS-Staat, documents the extraordinary, large-scale medical sabotage conducted by the prisoners working in the Buchenwald SS Hygiene Institute and producing a dud vaccine for SS combat units.

As Klemens Barbarowski reports, the matter received even more publicity when Dr Marian Ciepielowski, then [after the war] resident in the American occupation zone, “was approached by a big German pharmaceutical company with an extraordinary request. The company intended to produce typhus vaccine as practised at the Buchenwald institute of hygiene in the concentration camp near Weimar, but none of the tests carried out in their laboratories had given a positive result. The company’s physicians, bacteriologists, serologists, and chemists could not produce the vaccine, even though they were strictly following the Buchenwald method as presented in one of the issues of the German scientific medical journal Zeitschrift für Higiene und Infektionskrankheiten in 1944. So the company was requesting the Polish doctor who had been production manager at the Buchenwald institute of hygiene to kindly help them produce the vaccines using the method described in the said journal. That was the second time the Buchenwald prisoners were exposed as saboteurs who had discredited Nazi German science.”

The brain behind the sabotage was Dr Marian Ciepielowski, and those in the know were Dr Ludwik Fleck, Dr Makovicka, and a few others from the commando. Dr Ciepielowski, who died on 1 February 1973 at the age of 65, deserves closer attention thanks to his original, bold, and especially risky activity, undertaken despite the extremely adverse conditions at Buchenwald. He has gone down in the history of Buchenwald. After liberation, despite being exhausted by life in the camp and his chronic lung disease, Dr Ciepielowski vigorously embarked on medical work and organising a project to help Polish survivors in Germany. He also had the strength to build up a status of authority in the USA.

He was born on 30 August 1907, in Dzikowiec (near Lwów, in the Powiat4 of Kolbuszowa), the son of Walenty and Kazimiera née Majchrowicz. He attended Tarnowskie Góry grammar school and then went up to Kraków to study medicine. In 1929–1931 he was vice president of Bratnia Pomoc Medyków, a medical students’ fraternity at the time when the Dom Medyków, a medical students’ hall, was being built at Number 20 on the Grzegórzecka. By that time he was already known for his left-wing views and considered himself a socialist, though he was also a Catholic. In March 1934 he graduated from the Jagiellonian University Faculty of Medicine and subsequently worked in Katowice, Krosno, and Zbaraż.5 From April 1937 to September 1939 he worked in the Kraków Department of Microbiology and Serology, and for a social insurance company. He also worked with the Kraków Infectious Diseases Clinic, pulmonary tuberculosis being the subject of his special interest. As an expert on infectious diseases, he had the right qualifications for his later job as production manager in the Buchenwald hygiene institute, where he wrote numerous scientific papers for Ding-Schuler, and made observations and notes which he used later in his scientific papers published in the West. One of these papers, co-authored with Prof. Robert Waitz on experimental typhus fever in Buchenwald concentration camp, was published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim (1965: 68–69).

In September 1939, Dr Ciepielowski took part in the Polish defence campaign against the German invaders and thereafter was briefly interned in the USSR, but was probably already back in Kraków by October 1939. Drawn into clandestine resistance activities, he did not enjoy freedom for very long, because the Gestapo arrested him on the night of 1 April 1941, from Dr Morus’s apartment (at ul. Limanowskiego 44). After his apartment had been searched twice, he was interrogated in the Gestapo building (at Number 2 on the Pomorska) and imprisoned in the Montelupich jail. On the basis of a denunciation, he was accused of giving anti-German speeches, using violence against German airmen who had been taken prisoner during combat in the September campaign, etc. The accusations were vague and not based on evidence.

In the Montelupich prison he had a hard time, as he described it, along with some of his Buchenwald experiences, in a letter of 31 January 1947 to his sister:

At the very end of my imprisonment in the Montelupich jail, I was in the same cell as Capt. Szymanski of Kraków, and Menzel, an insurance clerk. When all the skylight windows were being walled up in the entire prison, some steel saws were found in our cell hidden in the window, which the bricklayer on the job . . . thoughtlessly or deliberately handed in to the Gestapo. After a summary trial, everyone in our cell was to be shot immediately. However, thanks to the splendid attitude of Capt. Szymanski, who spoke fluent German, and explained that the building was an old military prison dating back to Austrian times,6 after long deliberations and interrogations the matter ended with a three-day starvation sentence.

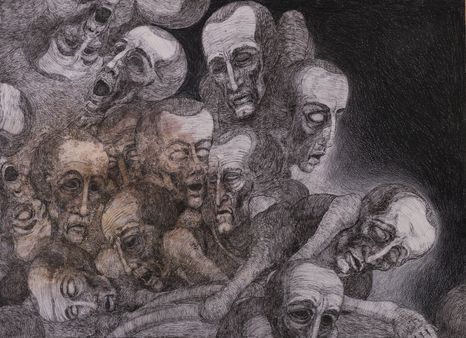

Rolling Back to the Camp. Marian Kołodziej. Photo by Piotr Markowski. Click to enlarge.

From the Montelupich prison, Dr Ciepielowski was sent to Buchenwald and there he received prisoner number 4367. He writes in the same letter:

My first year in Buchenwald was the time of the worst ordeals for Poles, and for me a full year with a shovel and pickaxe on roadworks. Every day people around me who were twice or three times stronger than me, were giving up and going down due to hunger and despair. Every day dozens of people were being clubbed or trodden to death, strangled in elaborate ways, shot or sadistically abused for days. Despite going through the same experience, despite having my right shoulder broken and undergoing very serious surgery for a phlegmon in the metacarpus of my right hand, during which a railway mechanic acting as chief surgeon cut right through my hand, in three attempts (granted—he did the incisions properly), because he was unable to find the source of the purulence. As a result, my right hand was stiff for a long time, but I still had to continue to work; there’s still no exteroceptive sensation in my first and middle fingers, and their mobility is impaired. However, to my own surprise I survived that year. My weight at that time was 46 kg (100 lbs.).

The following years in the camp were better for Dr Ciepielowski, because he no longer had to do physical labour, but was sent to the hygiene institute, and worked there from July 1943 to April 1945. Involvement in the camp’s underground resistance movement and the medical sabotage operation put his life at risk every day. A couple of times he was in danger of execution. The clashes and conflicts which unfortunately troubled the Buchenwald resistance movement, were not only an additional hindrance to Ciepielowski's work, but even landed him in tricky situations or put him in jeopardy. He was helped out by prisoner Eugen Kogon, who was a professor after the war. The journalist Dr Józef Matynia, a survivor and member of the underground PPR group7 at Buchenwald, wrote in a letter to me that Ciepielowski “was active in the underground peer committee [of Buchenwald], which was transformed in 1944 into an anti-fascist committee.”

Ciepielowski’s last days in Buchenwald before the arrival of American troops were a very difficult period. The camp’s Political Department (i.e. the Gestapo) were looking for him. In the letter to his sister he wrote, “after a week of hiding in the canals, cellars, and other nooks, I was finally released by American troops. Two hours after the troops had entered, I experienced one of the finest moments in my life, at our first meeting in a liberated Buchenwald, where I spoke on behalf of the Polish secret organisation.”

It happened on 11 April 1945. As a result of various intrigues, Ciepielowski did not return to Poland, to his beloved Kraków. He joined in the work to save the survivors, and for the next 5 years took care of them in several German provinces, in cities like Karlsruhe, Ludwigsburg, and others. In his letter of 1947 he writes about “the mad pace of work in Buchenwald and Weimar. We pulled Poles out of the dung, from stables, barns, and ditches; we furnished their residential quarters, outpatient clinics, hospitals, kitchens, and we taught Germans to treat us as people, not as rabble. Today we are still working in the same area of problems with the army and UNRRA,8 but opportunities for our work are very limited and restricted.” During this period he was a Polish Red Cross medical inspector for the provinces of Hessen, Württemberg, and Baden. From February 1948 to December 1951 he worked for the International Tracing Service of the Allied High Commission for Germany in the Exhumation and Identification Department, whose task was to prepare and file information about the victims who had been killed and died in the Nazi German concentration camps.

Having married a Polish survivor in (West) Germany, in 1951 he and his wife left for the United States. On 28 January 1952, he was employed in the Roosevelt Hospital, where he first worked in the laboratory and perfected his English. On 14 March 1962 his graduation certificate in Medicine was officially recognised in the USA and he was licensed to practise in medicine. His career progressed and he held more and more senior medical positions. Finally, on 1 August 1966, he was appointed deputy director of Roosevelt Hospital and held the post for over 7 years, until his death. He was a member of several learned societies and Polish diaspora organisations, such as the American Medical Society, the New Jersey Medical Society, the Middlesex County Medical Society, United Poles in America (at Perth Amboy, NJ). He was laid to rest on February 3, 1973 in the Resurrection Cemetery in Metuchen, New Jersey.

Despite many hardships, diseases and difficulties connected with his peregrinations far from his beloved homeland, Dr Ciepielowski preserved his serenity, was extremely obliging and kind-natured at work with his patients, and was loved by all.

The Buchenwald medical resistance movement is closely connected with the person of Dr Marian Ciepielowski and deserves to be remembered by posterity.

Translated from original article: Stanisław Kłodziński, “Sabotaż w buchenwaldzkim Instytucie Higieny SS. Dr Marian Ciepielowski.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1977.

- Rudolf Weigl (1883-1957), Polish biologist and pioneer of the first anti-typhus vaccine.

- Now Lviv (Ukraine); under German occupation the city was known as Lemberg.

- Paul Giroud (1898–1989), French physician and biologist, developed a vaccine against typhus.

- Powiat—Polish second-tier territorial administrative unit. After the War the City of Lwów found itself east of the new Polish border (viz. in the Soviet Union; it is now known as Lviv and is in Ukraine), while Dzikowiec is on the Polish side, about 120 km (75 miles) from the border, and 190 km (118 miles) west of Lviv.

- Now Zbarazh, Ukraine.

- I.e. prior to 1918, when Poland was restored as an independent country after 123 years of being partitioned between Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

- PPR—Polska Partia Robotnicza (the Polish Workers’ Party), the official name of the Polish Communist Party, which was illegal in prewar Poland, but officially enjoyed a good reputation after the war (and when this article was written) when the Communists took power.

- UNRRA—the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, an international relief organisation founded in 1943 to administer aid to war victims, especially to displaced persons in the aftermath of the Second World War.

All notes come from the translator, Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa.

References

-

Unpublished documents

- letter of 31 January 1947 from M. Ciepielowski in the American occupation zone to his sister, Ada Tokarska;

- information on M. Ciepielowski, recorded by Dr E. Kogon in Oberursel (Taunus, Germany) on 1 December 1947; +statement written in Hanau on 20 May 1947, by Stefan Szczepaniak, former leader of the Polish Clandestine Organisation in Buchenwald, former Chairman of the Polish Committee and manager of Buchenwald after liberation; at the time Szczepaniak was also Chairman of the Union of Poles in Germany and contemporary Board member of the World Union of Poles in London; +letters M. Ciepielowski received from survivors, family members and friends: Wanda Ciepielowska (from Metuchen, New Jersey), Stanislaw Fudala (from Jaroslaw), A. Gadzinski (from Opole), Dr. Romuald Gecow (from Warsaw), Stanislaw Gosiak (from Jedlicze), Rudolf Gottschalk (from Frankfurt-am-Main), Dr Jerzy Lebioda (from Kraków), Dr Józef Matynia (from Sopot), Helena Morusowa (from Kraków), Dr. Stanislaw Nowak (from Kraków), Kazimierz Olenderek (from Poznan), Jan Rajek (from Ostrów Wielkopolski), Dr Adam Syrek (from Tarnów), Ada Tokarska (from Jedlicze), and Dr Janku Vexler (from Paris);

-

Personal documents

- photocopy of Dr M. Ciepielowski’s personal ID card, mentioning his arrest

(Certificate of Incarceration) of 10 December 1951, no 23755 (issued by the Allied High Commission for Germany); - document stating as follows (full quote): “The State Board of Medical Examiners of New Jersey certifies that Marian Jacob Ciepielowski, M.D., has passed a satisfactory examination before this Board and is hereby licensed to practice Medicine and Surgery in the State of New Jersey. Nr 18675. Trenton, New Jersey, March 14, 1962. (—) President. (—) Secretary .”

- photocopy of Dr M. Ciepielowski’s personal ID card, mentioning his arrest

-

Posthumous information

- a short mention of M. Ciepielowski in Nasze Drogi. Czasopismo Stowarzyszenia Bylych Wiezniow Politycznych w Stanach Zjednoczonych i Kanadzie, 1973: 12, 39, (mimeograph);

- posthumous information (detached print) entitled “Memorial Obituary” of 2 February 1973 (The News Tribune, Perth Amboy, N. J.); Dr Marian Ciepielowski (posthumous note). In: Roosevelt Hospital. Three-year report 1971–1973 (photo album), p. 2;

- ”Non omnis moriar” (obituary). Nowy Dziennik, 1973: 3, 9.

-

Publications

- Barbarski, Klemens. 1947. “Sabotaz w ampulce.” Przekrój. 99: 16; Czarnecki, Waclaw, and Zonik, Zygmunt. 1969. Walczacy obóz Buchenwald. Introduction by F. Ryszka. Warszawa: Ksiazka i Wiedza, 59, 235, 242, 268, 270-273, 275, 283, 284, 377, and 378.

- Kogon, Eugen. 1947. Der SS-Staat. Das System der deutschen Konzentrationslager. Berlin- Tempelhof: Verlag der Frankfurter Hefte/Verlag des Druckhauses, 164, 275, 286;

- Waitz, Robert, and Ciepielowski, Marian. 1946. “Le typhus experimental au camp de Buchenwald.” La Presse Medicale. 23: 322ff. Polish version: “Doswiadczalny dur wysypkowy w obozie koncentracyjnym w Buchenwaldzie.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1965: 68–69.