Authors

Danuta Bystroń (married name Pytlik) and her fiancé Władysław Pytlik were PPS members who lived in Brzeszcze, a small place in the neighbourhood of the concentration camp. See Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. “Escapes and reports” at http://auschwitz.org/

Władysław Denikiewicz, MD, 1918–2006, nom-de-guerre Romek, contributor to Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, engaged in armed clandestine resistance against the Nazi Germany in Poland during the Second World War, emigrated to the United States in 1968 and was later a Vietnam War veteran; author of a few publications related to the anti-Nazi resistance in wartime Poland, help provided to the Auschwitz prisoners, and attempts to save the Jews.

Janina Kościuszkowa, MD, 1897–1974, Auschwitz-Birkenau survivor, No. 36319, Flossenbürg survivor. Prisoner-doctor in Montelupich prison (1943) and in Auschwitz-Birkenau (1943–1944). Witness in the Auschwitz trial (1947) and in the trial of Rudolf Höss (1946–1947).

Janina Kowalczykowa, MD, PhD, 1907–1970, anatomical pathologist, lectured on medicine in the Polish secret higher education system during the Second World War; held the Chair of Anatomical Pathology at the Kraków Medical Academy.

Jerzy Mostowski, Auschwitz survivor No. 17221

Edwin Opoczyński, MD, 1918–, born Edwin Bieberstein, Jewish-Polish surgeon, orthopaedist, and traumatologist, survivor of the Kraków Ghetto and concentration camps in Kraków-Płaszów, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Flossenbürg, and Oranienburg.

Tadeusz Szymański, MD, 1917–2002, Auschwitz survivor (prisoner No. 11785), one of the founders and a longtime curator of the Auschwitz Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

Maria Bobrzecka

Danuta Pytlik

The pharmacist Maria Bobrzecka was born on 4 February 1898 in Tarnów. She started her professional career in 1919, and in 1927 became the proprietor of a pharmacy in Brzeszcze.1 In her work she was sensitive to all in need, which earned her the reputation of an upright, truly humanitarian person with the local people. In the years preceding the War, she took part in a local educational campaign and delivered public lectures.

In the autumn of 1939, the German occupying authorities appropriated Maria’s pharmacy, but employed her to manage it.

The wartime period of Poland’s occupation by Nazi Germany was full of situations when Maria’s character as a people-friendly and patriotic individual came to the fore. The ruthless measures the Germans imposed against all Polish people did not make her change her conduct. Her pharmacy was in the immediate vicinity of Auschwitz, and from the very beginning of the camp’s operations, she was profoundly committed to providing aid for its inmates. She offered various types ofassistance, though usually it was supplying medicines to prisoners working in the outside commandos. She did this either through her personal contacts or by using the intermediary services of women’s groups in the neighbourhood of the camp. Not only did she make use of her personal contacts with prisoners to send in medications, but also acted as a go-between for the despatch of their secret letters to their families, asher extant correspondence shows.

Maria selflessly continued her efforts to provide aid for prisoners and help them survive throughout the War, even though it would have put her at risk of very serious reprisals from the Gestapo if she were caught. She was a member of a PPS2 resistance group and joined in the work of other local resistance groups, such as those operating under the auspices of the BCh3 or the AK.4 She provided medical supplies for all of these groups. In 1944 a secret aid group known as PWOK5 operating in the immediate neighbourhood of Auschwitz established contact with the head of a medical supplies warehouse in Katowice, and PWOK’s liaison girl delivered the first 20 kg batch of medications to Brzeszcze. Regardless of the risk she was taking, Maria agreed to use her pharmacy as a secret distribution centre, and the next two consignments were addressed to the pharmacy and sent by post. Next she sorted the medications and put them into small parcels which were addressed to bogus prisoner numbers6 and sent to the concentration camp.

Oil painting portrait of Maria Bobrzecka by M. Niedźwiedzka, ca. 1935. Source: Jagiellonian University Medical College collections, Museum of Pharmacy in Kraków. Click the image to enlarge.

The extent of Maria’s clandestine aid was considerable: apart from catering for the main camp and its environs, she also sent supplies to units belonging to other concentration camps and POW camps in Germany. And she managed to keep her work so discreet that the Gestapo never discovered who was behind the provision of such substantial relief for the prisoners.

The thank-you letters Maria received from individual survivors and a group of Hungarian prisoners throw light on her work under German occupation. Of the many letters she received, I shall quote just one passage from a letter sent to her soon after the War was over by the Gliwice branch of the union of concentration camp survivors7 who were held as political prisoners:

We, the few who survived, would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to you for the constant and enduring assistance you, an honest and true Polish woman, gave us. Please accept our profound and sincere thanks, expressed in the Old Polish saying, “May God reward you,” for all that you did for us.

I must also mention that following liberation, Maria Bobrzecka provided effective material assistance and medicines free of charge to 195 survivors who were patients in Brzeszcze hospital. She provided her wartime services with commendable modesty, and was always very reticent about what she had done, and she regarded this particularly arduous and self-sacrificing period in her career simply as a citizen’s duty.

Maria Bobrzecka died in Kraków on 27 August 1957.

Others who rendered similar services to aid Auschwitz prisoners and are now deceased were the physicians Dr Władysław Dziewoński, who died in Kęty8 in 1946, and Dr Józef Sierankiewcz, who died in Brzeszcze in 1946, and pharmacists Marian Kwiatkowski of Oświęcim and Eustachy Sokalski, the manager of a pharmacy in Kęty.

Zygmunt Klemensiewicz, head of the Kraków branch of the Social Insurance Company, and his deputy Col. Stanisław Plappert were two other persons who provided medicines, clothing, and food for Auschwitz prisoners, working in co-operation with local resistance groups active in the vicinity of the camp but independently of the persons I have already mentioned. Both died in Kraków after the War.

Professor Marian Gieszczykiewicz

Janina Kowalczykowa

Auschwitz was a Vernichtungslager (a death camp), so every prisoner who had his wits about him should have known that for him there was only one way to leave the camp—with the smoke from the chimney of the crematorium. Nonetheless, there were those who “hoped against hope” that they would survive. What’s more, the Germans feared that someone who was supposed to die would come out of Auschwitz alive. So they had the registration cards of such prisoners marked “N. N.” (Nacht und Nebel9 —“Night and Fog”). Such prisoners already had a death sentence attending them as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz, to hasten on their death, which was an inevitability in any case.

Prof. Marian Gieszczykiewicz at work. Source: The National Digital Archives of Poland. Click the image to enlarge.

That is what happened to Professor Marian Gieszczykiewicz. Today[1961] he would have been 71. He was born on 21 May 1889. He read Medicine at the Faculty of Medicine of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, and started out on his medical career at the age of 20 on a voluntary internship in the Department of Microbiology. Within a decade in the Department, he had been promoted to Docent,10 and by the end of 20 years’ work he was appointed its Professor.

Professor Gieszczykiewicz conducted a series of projects and published on bacteriology, serology, and epidemiology. He is commended especially for his work on bacteriology.

At the beginning of the War he was evacuated to Lwów11 with the Fifth Regional Hospital. In December 1939, after his return to Kraków,12 he resumed university teaching for medical students on the secret university scheme13 and worked on a new textbook, and he was also deeply engaged in the underground resistance movement against the Germans. He was very daring and had but one regret about which he told his wife: he had to break off his intensive scientific work, at a time when his Department was so well organised that he could well have spread his wings to continue his scientific research.

But in November 1941 the Germans arrested him and kept him in the Montelupich prison14 until June 1942. On 11 June 1942, after six months in the Montelupich, they sent him to Auschwitz, where he was registered as No. 39197. On arrival he was in a state of total depression, convinced that he could have avoided arrest if the resistance unit he was in had been better organised. In Auschwitz a group of friends and colleagues, physicians and medical students who were fellow inmates, took care of him and managed to get him into the prisoners’ hospital to keep him away from the hardships of life in the camp. They were even thinking of setting up a little bacteriological lab for him. But after six weeks in the camp, Professor Gieszczykiewicz was summoned to report to the Politische Abteilung (political department). We all knew what that meant. To protect him, the clerk of the hospital wrote on the summons that Professor Gieszczykiewicz was seriously ill and transportunfähig (not fit to travel). Sometimes an attempt of this kind to postpone a doomed prisoner’s execution could even save his life. Unfortunately, within a couple of hours a second summons arrived, saying that if Professor Gieszcykowski was unfit to travel, he was to be carried to Block 1115 on a stretcher, and it was to be done at once. I spoke to one of the prisoners who carried Professor Gieszczykiewicz, who had to pretend he was very ill. The officer who conducted executions had left before the Professor arrived in Block 11. Rapportführer Palitzsch16 fell into a frenzy and shouted furiously, “Why so late?” (it was 11 o’clock in the morning), went up to the stretcher and fired two shots at the Professor. He then ordered the body carried back on the same stretcher to Block 28. In the afternoon the Professor’s colleagues took him to the crematorium.

That’s how the distinguished Polish scientist Marian Gieszczykiewicz died, on 31 July 1942 in Auschwitz. He was an outstanding academic and university tutor, treasured in our memories as a man of integrity who fought fearlessly for his beloved Country.

One of the documents the Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland17 has found in Professor Gieszczykiewicz’s file kept in the Auschwitz records is a notice confirming his death with a medical statement signed byLagerarzt Dr Entress,18 which says that the cause of death was Cachexia beim Darmkatarrh (cachexia (debilitation) and intestinal catarrh).

Dr Franciszek Gralla

Tadeusz Szymański

People whose knowledge of what it was like in the Nazi German concentration camps comes only from what they have read, heard from others, or from the films they have seen, tend to think that all the inmates imprisoned in the concentration camps must definitely have hated all Germans. However, most of the prisoners the SS put in the red triangle category19—here I mean German nationals classified as “political offenders”—were intransigent opponents of the Hitler regime, and some were even Polish patriots. One of them was our colleague, Dr Franciszek Gralla.

Dr Gralla was a native of Silesia.20 He was born in Gleiwitz21 on 2 October 1905. He studied at the Universities of Innsbruck, Vienna, and Breslau,22 and graduated in medicine from the University of Breslau in 1935. Next he completed a specialist course inneurology and psychiatry in Professor Lange’s neurological clinic in Breslau. Dr Gralla lived and worked in Breslau until his arrest. The Nazi authorities put him under surveillance, because he wasagainst the Hitler regime, and quite open about it, and had friends and acquaintances who shared the same views and could not accept the way the Nazis were violating human dignity and destroying lives. He could not find permanent employment and had to work as a part-time replacement doctor for the social insurance company.

He was arrested for the first time in September 1939, following Hitler’s invasion of Poland, and was held in prison for 7 weeks for being an activist of the local Polish community. He was arrested a second time in 1940, in connection with a failed attempt to assassinate Hitler, which occurred in Munich. 300 political suspects were rounded up at the time. Dr Gralla was detained in Breslau and held in the Kletschaustrasse prison for 6 weeks.In March 1941 he was arrested a third time and sent to Auschwitz without a trial. While he was in prison a daughter was born to him, but he never saw her.

Dr Gralla arrived in Auschwitz in October 1941. He was registered as No. 21938 and categorised as a “Reichsdeutsch23 political offender,” which got him a job as a physician in the admissions room of the prisoners’ hospital in the main camp. He worked in this capacity until April 1943. Next, he was transferred to the isolation hospital in the Roma family camp,24 but in the autumn of that year he was sent back to the main camp and put in Block 28, which was an important venue for prisoners’ undercover political affairs. There he worked first as block elder, and subsequently as a physician in the admissions room, which meant that he came in contact with a lot of fellow-prisoners. At first they treated him with a fair amount of caution, thinking he was a Reichsdeutsche, but soon they saw that he could be trusted as a conscientious, self-disciplined and helpful colleague, which made him popular andgenerally well-liked by fellow prisoners.

Dr Gralla had a reputation as a physician well-versed in neurology and steadfast in his commitment to medical ethics. He was a dedicated, self-sacrificing carer for his patients, for whom so little could be done in the conditions prevalent in the camp.

By nature Dr Gralla kept himself to himself and was rather reticent, cautious and self-disciplined in his relations with the camp’s authorities. These virtues earned him a good reputation with the SS men, which facilitated the secret resistance efforts undertaken by the prisoners in his block. Dr Gralla supported and worked with a group of communists who wanted to remove the criminals, most of whom were Germans, from the offices they held, and curtail the influence these prisoners exerted on life in the camp. For a fuller depiction of Dr Gralla’s character, it must be said that in his everyday business he was always composed and cheerful. Usually he spoke the Silesian dialect of Polish, creating an air of wholesome, hearty humour. His colleagues nicknamed him “Tukaj, ” because that’s how he pronounced the Polish word tutaj.25

In 1944 the German authorities started on a partial evacuation of the camp. In August 1944 Dr Gralla was in a group of prisoners evacuated to Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg, where he was registered as prisoner no. 47887. A few days before the end of hostilities, this camp was evacuated and about eight and a half thousand prisoners were put on boardthe Cap Arcona and the Thielbeck. On 3 May 1945 these ships were bombed by Allied planes. Only about 700 prisoners survived.26

Dr Gralla was on the Cap Arcona, sharing a cabin with 11 other prisoners of various nationalities. Out of this group Dr Okła, a Polish physician, survived.

Our colleague Dr Franciszek Gralla died five days27 before the end of the War. He died a democrat, a wise and ethical physician, a man of integrity, a fellow prisoner we shall never forget.

Dr Stefania Kościuszkowa

Janina Kościuszkowa

Dr Stefania Kościuszkowa completed her grammar school education in Jasło and graduated in medicine from the Jagiellonian University Medical Faculty in 1924. On graduation and subsequently as a fully qualified medical practitioner, she worked in the children’s ward of St. Louis’ Hospital,28 whose chief physician at the time was Professor Bujak.29 After qualifying as a specialist in paediatrics, she moved to Łańcut30 for family reasons and continued to work as a physician.

In 1929 she attended a training course in Warsaw for the treatment of tuberculosis and set up one of the first anti-TB advisory centres in provincial Poland, equipping it with an X-ray facility provided by her husband.

The couple worked selflessly and with full dedication, providing medical care not only for the Powiat31 of Łańcut. Patients from adjoining powiats came to Łańcut for treatment. The Łańcut advisory centre caught the attention of members of the government, who came to see it when they were in Łańcut. It was one of Poland’spioneer centres for the treatment of tuberculosis.

In 1934, after her husband’s death, Dr Stefania moved to Rabka32 and worked in the children’s ward of the officers’ rest home. Later she ran a boarding school offering preventive care for children at risk of developing TB. This institution was financed by the national social insurance company.

When the War broke out, Rabka found itself with a shortage of doctors. Dr Kościuszkowa worked with the utmost dedication and did not deny assistance to resistance fighters in need of medical treatment. After the War she was posthumously awarded a military distinction and promoted to the rank of second lieutenant under her nom-de-guerre “Biała.”

In June 1942, the local Gestapo unit in Rabka discovered evidence of the activities of an underground resistance organisation operating in the area and fell into a frenzy, arresting Dr Kościuszkowa, another dozen women, and several men.

She was taken to the Palace Hotel33 in Zakopane, from there to Tarnow Prison, and shortly afterwards (on 28 July 1942) to Auschwitz. On the way there, she looked after her fellow-prisoners, several of whom died in her arms.

August 1942 was the worst period for women prisoners. They were being transferred from the main camp to Birkenau and accommodated in barracks built of clay bricks and stones in which well over ten thousand Soviet POWs had perished. For the women this was the pit of despair and misery.

The hunger, dirt, and the lice that ravaged the camp, along with the shortage of water which made it impossible for prisoners to wash and keep themselves and their clothes clean—all these things gave rise to the outbreak of various diseases. There were no medicines. Health workers were only starting to organise a medical service.

Step by step, gradually Polish women got jobs in the prisoners’ hospital, first as Nachtwache (night watch) and cleaners (or putzerki in the prisoners’ jargon, from the German Putzerinnen). Thanks to their self-denying, hard work, by the end of 1942 there were no more German women on the staff of the prisoners’ hospital, and all the jobs were in the hands of Polish girls.

Dr Stefania Kościuszkowa was the first woman prisoner doctor, but she started as a Nachtwache, her job was carrying out the excrement buckets and disposing of their contents. The heavy buckets were a terrible strain on her, and often made her fall down if she slipped on the wet dirt floor. There were no proper floors at the time, not even ones made of bricks.

She could not let the authorities and functionaries know she was a doctor. But she did not give up her job as a Nachtwache, because it was the only way in which she could help her sick friends.

Between carrying out the slops and disposing of the dead bodies, she always found time to secretly examine the patients. One day she was caught doing that by Schwester Klara,34 who slapped her face and threw her out of the hospital.

Dr Kościuszkowa started working as a physician in the camp. At the time sick inmates were afraid of being sent to the hospital, so they were grateful for any care they could get in their block. She was ready to help at any time of the day or night. She would clamber up to the top bunks, and was into the secret of how to procure medications. There was no running water in the hospital at the time, so she organised a system to bring in the much needed water and herbs, creating conditions that started to resemble an environment fit for humans. Sometimes, if she did not have the required medicine, a kind word would cheer up her patient and help to save her life.

In her book Smoke over Birkenau, Seweryna Szmaglewska35 writes affectionately about Dr Kościuszkowa, for instance in this passage on page 42 (of the Polish edition36):

You could see her grey hair and withered little face, all the time attending the patients who were the most seriously ill. For so many eyes the sight of this slight figure kindled a warm glow of trust and consolation. You could see by the way she moved and behaved, and by the expression on her face that she was carrying out an important mission. She issued very clear instructions that she wanted to be woken up at any time of the night whenever anyone needed her. Her patients knew that. They felt safe under her kindly care... it was much easier to be ill, and much easier to die in the hands of such a doctor, hands that trembled with concern for them. But there came a day when the avalanche of death swept away the good Dr Kościuszko, leaving hundreds and thousands of patients waiting for her in vain.

In January 1943, Dr Kościuszko went down with a serious condition herself. Durchfall (diarrhoea due to starvation), not fully healed frostbite, combined with abscesses and erysipelas killed her on 11 January 1943.

Dr Jan Kowalczyk

Władysław Denikiewicz

Dr Jan Kowalczyk was born in Kraków on 22 June 1903. He graduated in Medicine from the Medical Faculty of the Jagiellonian University and obtained his training in surgery under the supervision of Professor Jan Glatzel.37 Not only was he Glatzel’s student, but also his most devoted friend. He did not abandon his tutor at the most difficult time, when Glatzel was very seriously ill for a very long time. Dr Kowalczyk was at his side to the very end.

After the War, Dr Kowalczyk obtained his habilitation38 and was appointed docent. He was an extremely meticulous physician, and excellent diagnostician, a cool-headed and circumspect surgeon, and fully dedicated to his work in the hospital and clinic. In his scientific work he was thoroughgoing and could not stand sloppiness and pretentiousness. He left a legacy of around 30 papers, all of them models of attention to detail and creative contributions to the store of medical knowledge. Although he did not live long enough to consolidate a set of features characteristic of his work, he educated a group of students, giving them a thorough training in surgery and introducing them to scientific research. For a short time he was head of the surgery ward of St. John’s Municipal Hospital. Hewas appointed to this post by the Medical Faculty, and upgraded that fairly small ward to the status of a good clinic.

Dr Kowalczyk was well-known for his outstanding intellect and wide range of interests. He was an expert on Polish literature, philosophy, and a collector of coins and stamps.

All these features underpinned his activities in the resistance movement under the wartime Nazi German occupation of Poland, making his endeavours stand out all the more. He knew very well that every time he provided medical services for the resistance movement he was risking his life, yet he made a wholehearted commitment to helping sick and wounded soldiers in the service of the Polish Underground State.39 For them he was on call at any time of the day or night. He and Professor Glatzel admitted resistance activists whose names were on the German wanted list to the clinic, and later to two other medical institutions40 on the pretence of treatment. Sometimes, for the sake of security, he would conduct a fake operation, for instance the removal of an appendix or some other surgery involving just a superficial cut on the endangered person’s abdomen to leave a post-op scar. In the period when the resistance movement was establishing regular combat units, Dr Kowalczyk served as physician to one of them known as Żelbet41 (Reinforced Concrete), and operated one of its men, Cpl. “Rezuła” (Tadeusz Żuwała), who was rushed into hospital straight from the unit’s forest hideout, this time with a genuine and urgent case of appendicitis. The operation was carried out in a medical centre on ul. św. Filipa. When the prisoners’ resistance movement inside Auschwitz (under the leadership of Józef Cyrankiewicz42) had reached the point when it could start organising escapes, almost all of the successful fugitives who came to Kraków needed to be seen by a doctor. Dr Kowalczyk was one of the few physicians who examined them, provided treatment and performed surgery to remove the prison number tattooed on their skin. He obliterated the “concentration camp IDs” of Tomek Sobański, Kostek Jagiełło,43 Szymek Wojnarek, and the Austrian Communist Josef “Pepi” Meisel,44 who is now Secretary of the Communist Party of Austria.

In July 1943 Marian Bomba,45 commander of the PPS People’s Guard46 combat unit for the Kraków District and for combat units in the Oświęcim area, was seriously wounded in a skirmish with the German police on ul. Dietla. One of the trusted surgeons denied his assistance, because the entire Gestapo and other police units had been alerted and were out to apprehend the wounded man. Then the organisation’s command asked Dr Kowalczyk for help; he had no hesitations and agreed at once. Without wasting time talking, he just took his doctor’s bag and went to the house where the wounded man was waiting. He continued to treat him for the entire duration of his illness, and after a few months Bomba was fit enough to cross two borders illegally, get to Budapest, and be back quite soon to continue fighting against the Germans and providing aid for prisoners in the concentration camps, particularly Auschwitz. Marian Bomba died in the spring of 1960.

Dr Kowalczyk died of a heart attack on 26 April 1958. He was an ardent patriot, a distinguished physician, scientist, and academic tutor, truly human in the best sense of the word, always ready to come to the aid of all who needed his assistance regardless of race, religion, or political views.

Dr Henryk Krause

Edwin Opoczyński

Dr Henryk Krause came from Kielce and before the War worked in his hometown for the national social insurance company. He enjoyed a good reputation as a helpful and responsive physician. He was Jewish and was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Once there, he quickly earned the confidence and respectof his fellow prisoners. He worked gratuitously and selflessly. He was transferred to another concentration camp and died in unknown circumstances.

Dr Witold Kulesza

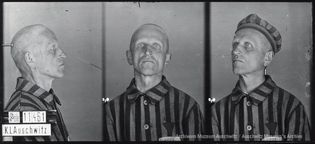

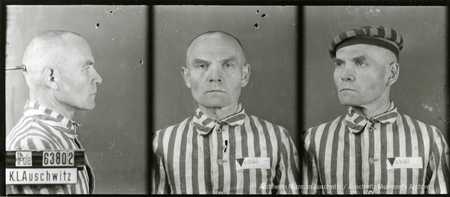

Dr Witold Kulesza’s mug shot from Auschwitz. Source: Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Click the image to enlarge.

Dr Witold Kulesza was always calm and self-controlled, fully dedicated to his patients, and enjoyed their confidence both as an individual and as a physician. He worked in the Birkenau Krankenbau (prisoners’ hospital) practically from the beginning of its establishment. His life in the camp was connected with the Roma family camp,47 where he worked for 16 months. When the Roma family camp was closed down, Häftling Oberarzt (chief prisoner doctor) Kulesza was sent to the penal company. His friends managed to get him out of it and have him reinstated in the Birkenau prisoners’ hospital.

Whenever Dr Kulesza spoke to his patients, he bolstered their determination to survive and continue fighting for their lives. He survived himself but was left seriously ill. After the War, he settled in Ostrów Mazowiecka and died after a couple of heart attacks.

Dr Jan Malinowski

Dr Jan Malinowski came from a village in the neighbourhood of Krosno. In 1921–1927 he was a student at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. At university he was a member of several progressive students’ organisations, and used to say he was a close associate of Wanda Wasilewska.48 After graduating, he settled in Łódź, and alongside his professional work engaged in social work on behalf of the Society for the Workers’ University49 and workin gmen’s sports clubs. Those who knew him say he was always penniless, because he donated all of his income to help impoverished students.

In 1939 he fled Łódź and settled in Radom but was arrested and imprisoned in the local jail. In June 1943, after a long period of imprisonment, he was sent to Auschwitz. On several occasions during the initial period of his confinement in Auschwitz, he was summoned to report to the political department, and always came back injured and bruised after having been beaten up. Yet such experiences left him undaunted; he was a cheerful character and believed that eventually social justice would come out victorious.

When the prisoners’ hospital was moved to new barracks, Dr Malinowski worked in the infectious diseases ward until January 1945. He was always very modest, ready to help, and shared whatever he had with fellow prisoners. In January 1945 he was evacuated to Germany. As soon as the War was over, he returned to Poland and was appointed head of a hospital in Legnica. He was 44 at the time and set about his new duties full of enthusiasm. He was an insomniac, and one night sat on a second-floor window sill and dozed off. He woke up suddenly, lost his balance, fell and was killed on the spot.

(From the recollections ofAuschwitz survivor Kazimierz Smoleń50)

Dr Ernestyna Michalikowa

Janina Kościuszkowa

Dr Ernestyna Michalikowa graduated from the Jagiellonian University Medical Facultyand worked for several years in the Third Gynaecology and Obstetrics Ward of St. Lazarus’ Hospital. Later she worked as a self-employed gynaecologist.

She was an amateur aviator. She and her husband, who was a pilot and a physician, had a small aircraft of their own and flew to Spain, Hungary, Bulgaria, and made domestic flights in Poland.

When the War broke out, she was left on her own; her husband was an army doctor, and when combat operations were over, he left the country.

Ernestyna engaged wholeheartedly in the Polish resistance movement. She had no family members to worry about, and perhaps her involvement in the matters entrusted to her was too bold or went over the bounds of what was wise. She made the whole of her apartment available to the underground organisation she belonged to. It was used for secret meetings, editing a clandestine broadsheet, and listening to foreign radio broadcasts. She also kept a duplicator on the premises, along with a lot of reserve tubes of ink, Kennkarte (German ID) forms, and blank forms for baptismal and marriage certificates, plus a collection of stamps and seals used by various parishes. On 11 February 1942 the Gestapo had a field day when they swooped down on her flat and impounded all these items.

The Gestapo men were amazed by the importance of many of the things in the cache. They called the incident “the Michalik Affair” and set up a trap in the apartment and kept it running for three days. Anyone who knocked on her door was arrested, and about a hundred persons were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. Not many survived.

Dr Ernestyna was held for a year in the Montelupich prison. At first she was not allowed to work at all, and was even put in a dungeon. For the last three months she worked as a prison doctor in the women’s sectionaccommodated in the Helcel old people’s home.51

In May 1943 she was sent to Auschwitz. When she arrived, the prisoners’ hospital had already started to operate on an organised basis, with Polish doctors and nurses. Thanks to this, she could work as a doctor in the prisoners’ hospital, despite the fact that on arrival she had been assigned to the penal commando and had a Fluchtpunkt badge52 (a red circle in a white border around its circumference) on her back.

Dr Michalikowa was sent to work in the dispensary. All the sick prisoners who were to be admitted to the hospital had to pass through the dispensary. Thanks to Dr Michalikowa’s brave and determined attitude, not only women in a serious or hopeless condition were admitted, but also ones who were so exhausted and debilitated that a respite away from the roll calls and work out of doors could save their lives. The hospital filled up with young and old women, Polish, Yugoslav, French and Russian women, who could look forward to medical treatment there and survival. The hospital took in patients of all nationalities—there was no German racism within its walls.

Though working in the dispensary was not easy at all, under the prying eyes of German nurses and wardens constantly interfering with admissions, yet with a bit of good will and a considerate approach, Dr Michalikowa managed to do a lot of good.

Next, she worked as a surgeon, pioneering what would later become the surgical ward in the Birkenau women prisoners’ hospital. Alas, she did not live to see it opened. Utterly exhausted by her long imprisonment followed by confinement in Auschwitz, and debilitated by starvation diarrhoea, she contracted tuberculosis and died in November 1943.

Dr Witold Preiss

Janina Kowalczykowa

Dr Witold Preiss was born on 19 January1908 in Brylińce near Przemyśl. In 1926–1934 he studied Medicine at the Jagiellonian University, and while still an undergraduate worked as an assistant in the Chair of General and Experimental Pathology, as well as for the emergency ambulance service. After graduating he completed an internship in surgery, first in the Kraków Military Hospital, continuing in the Gabriel Narutowicz Hospital in Kraków, and subsequently received a physician’s appointment in the latter hospital. Until the outbreak of the War he was also an assistant in the Chair of Pathology at the Jagiellonian University Faculty of Medicine.

When the War started, he joined the ZWZ53 resistance movement, and never hesitated to undertake the most challenging tasks he was ordered to carry out. The ZWZ had a wide network of links; the work was dangerous and carried a lot of responsibility. Members of the organisation started to be arrested. On 4 December 1941 the Gestapo arrested Dr Preiss, his wife, and their housekeeper. The Gestapo wanted to send their children to a children’s home, but the couple managed to make them relent and put the children under the care of their grandmother. Dr Preiss was subjected to a series of very strenuous interrogations, which were held in several places apart from the Gestapo headquarters on ul. Pomorska. The Gestapo men who interrogated and beat him up were Johann Wośny,54 a Silesian who changed his pre-war name, Jan Woźny, to a more German-sounding one, and Christiansen,55 believed to be Danish. On two occasions Dr Preiss was taken to his own apartment for an interrogation; on one occasion he was interrogated in Warsaw, and on another in Cieszyn. At this time, about 60 persons were arrested within 3 weeks. In the first phase of the interrogations he sustained such heavy injuries that the Germans offered to send him to hospital, but he did not take up the offer and preferred to stay in his cell. They told his mother, who used to come to the Gestapo to get any news she could about him, that he was “a proud and adamant Pole.” At first Dr Preiss was confined in the Montelupich prison, where he provided medical treatment for other inmates, especially for women prisoners.

On 17 June 1942 he was sent to Auschwitz; alas, a death sentence had already been passed on him. He was registered in the camp as prisoner No. 39594.

Dr Preiss’s fellow inmates in Auschwitz, especially his closest friend Stanisław Głowa, say that he was stalwart and very brave. Dr Preiss was a prisoner doctor on Block 20 and did all he could—within the narrow scope of his powers—to help his patients. When he distributed medicines, he always considered very carefully which of his patients was most in need of them. He performed secret operations and cut abscesses, which were one of the most common ailments in Auschwitz. And he comforted other inmates to keep their spirits up. Dr Preiss knew he was going to die, as he often said to Stanisław Głowa, “They’re going to smash us all up, you’ll see. ” Głowa was the clerk of Block 20, and on the morning of 21 September 1942 he was due to escort Dr Preiss and the other prisoners who had been selected to the political department. He learned of this the previous evening, but could not bring himself to tell Dr Preiss. That night he could not sleep, and it was only in the morning that he had the courage to tell him the bad news. Dr Preiss replied that he could not get any sleep, either, and had sensed a foreboding of the worst. He went along with the others to the political department. An hour later, when they were all being taken to their deaths in Block 11, Dr Preiss was supporting a Muselmann.56 As he was passing Głowa in front of Block 20, he put a finger to his forehead to show that he would be shot. After the execution, Głowa saw Dr Preiss’s body in Block 28, waiting to be cremated. Dr Preiss had a bullet holein the back of the head; he had been shot at close range. His body was sent to the small crematorium. The execution had been carried out by a short, dark-haired Rumanian SS-man whom everybody knew.

Dr Preiss’s wife, who had been released, received a laconic telegram which said, “Your husband has died in the camp. ” Juliusz Twardowski, a relative of Dr Preiss who worked in the RGO,57 sent a request to the commandant’s office in Auschwitz, asking for the cause of death, and received the reply that it was Kachexie beim Darmkatarrh, that is cachexia (debilitation) and intestinal catarrh.58

(Information relating to the life of Dr Witold Preiss has beenprovided by his wife Krystyna, who was arrested with him.)

Dr Zbigniew Szawłowski

Edwin Opoczyński

Dr Zbigniew Szawłowski came from Warsaw and wasa prisoner doctor in one of the hospital blocks of Birkenau. Later he was chief physician in Block18. As a graduate of the military medical college in Warsaw,59 he was very self-disciplined himself and expectedthe same of others. On the surface, he seemed brusque and inflexible, but in reality this young doctor, just 27 at the time, had a heart of gold. He looked quite healthy, but in fact was suffering from tuberculosis which had already wreaked havoc in his lungs. He had several haemorrhages while confined in Birkenau, and later during his imprisonment in the Leitmeritz60 concentration camp in the Czech Sudetes. He survived the concentration camps, but died in a TB sanatorium a few months after the War. The hard and inhumane conditions in the camps were a formidable challenge to the prisoner doctors confined in them, yet many of these doctors managed to carry out their professional duties, even at the cost of their own health or life.

Dr Wilhelm Türschmid61

Jerzy Mostowski

Dr Wilhelm Türschmid’s German name and the rumour that he was a Reichsdeutsche62 made many people who had known him before the War treat him with a certain amount of reserve and caution. The whole of Tarnów knew him, after all he had been the chief physician of the local hospital63 since 1927. He was a first-rate surgeon and an excellent internist. He had a heart of gold and was considerate and sensitive to the misfortunes of others. Patients from a working class or peasant background wanted to have him as their doctor.

The stories that he was a German citizen seemed quite plausible due to the fact that his wife was German. But he sent his two sons to Polish schools. The fact that he felt Polish and was deeply distressed by the repressive measures imposed by the Germans against Poles was confirmed by his conduct with regard to his own wife, from whom he separated.

Dr Türschmid had strong emotional bonds with Tarnów and its people, so he did not deny his assistance to the local underground resistance movement when asked; indeed, he made a deep personal commitment to organising and developing the local AK64 combat units. His apartment in a fine house on ul. Starowolskiego was often used as the venue for secret meetings of their commanding officers. The tales of his German background provided a good smokescreen, which made Gestapo agents and snoops leave him alone. But only for a time. The day came when the Gestapo realised that “their man” was in fact a Pole and a fighter. The evidence was irrefutable. DrTürschmid was clapped in jail, subjected to a series of notorious interrogations in the Gestapo HQ on ul. Urszulańska, and expedited to Auschwitz, where he was registered as No. 11461.

In Auschwitz Dr Türschmid not only had his hands full of work as a medical professional, but he was also faced with a special moral and political task to fulfil with regard to his compatriots. We remember him in Block 21 in the last months of 1941. One of the prisoners hurt his finger with a chisel at work in the DAW65 commando. Two days later, he came to the prisoner’s hospital with a swollen finger, was sent to Dr Türschmid’s ward and had a dressing applied. Three days later he was back for a check-up. Dr Türschmid’s pale blue eyes looked down from under his bushy brows at the finger. He carefully removed the Ichthyol-impregnated cellulose dressing and examined the finger. “It’s not so bad, sonny, ” he said, “we won’t be operating. ” When the patient saw a piece of bone surrounded by dead tissue, he went dizzy, saw stars, and slumped down onto the floor of the dispensary. After a while, when he opened his eyes he saw Dr Türschmid, now with a serious and intent face, leaning over him. The doctor pinched his cheek, smiled, and muttered, “It’s all over now, son. You’ll soon be right as rain. ” The injured finger was in a rigid bandage. Dr Türschmid took advantage of the fact that the patient had passed out to apply the dressing neatly and quickly. Next time the patient called, he plucked up the courage to tell the doctor he remembered him from Tarnów. That made Dr Türschmid happy. He gave the fellow a warm, fatherly look and must have been thinking of his sons. He got very excited whenever he could talk about those bygone times. Everyone who could remind him of them aroused his interest and got special, sometimes invaluable care from him. I remember that in spite of the nightmare we were in, Dr Türschmid was able to cheer us up with his special kind of humour and even crack a joke or two. We all liked him, because for us he was not just a doctor, but also a good man, a decent fellow who was going through the same hardships as us.

Another prisoner admitted to the hospital in mid-September 1941 had a fairly large abscess on his left foot. He had the abscess cut and was put on the top level of a double bunk, next to another patient, and after that man’s death on his own. There was a separate room where patients had their dressings changed, but only if there were any dressings to be had. On days when that happened, Drs Türschmid and Pizło66 worked from morning to night attending patients, even though the hospital’s food supplies were not at all normal, not to mention the conditions in which the patients were kept.

When this prisoner realised that he would be having his dressings changed quite seldom, he asked the doctor shyly if he could possibly have a couple of extra bandages, dressings and some ointmentto keep in his bunk. Dr Türschmid explained in a whisper that it couldn’t be done, but applied a lot of ointment and cellulose dressings, and put three bandages on his wound. He wasted no words, but the patient understood at once what it meant, and when he got back to his bunk quickly took off two of the bandages, rolled them up, removed the extra dressings and salve, and hid them under his mattress. The wounds on his foot were still exuding a lot of pus, but in cahoots with Dr Türschmid and with sparing use of the stuff, he managed to change his dressing once a day.

After a few days, when Dr Türschmid saw him again in the dressing room, he smiled and asked, “Enough?” That was all he said. He knew very well that in the conditions we were in at the end of 1941, he could not have done any more than what he did.

However, the Gestapo was watchful. The political department became interested in Dr Türschmid. One day at the beginning of 1942, he was summoned to report to them. He and some others were sent out from the main office in Block 24 to Block 11. And there, at Death Wall, Prisoner Number 11461 stood his last. He was shot for being Polish and a fighter.

(Some of the above information comes from Tadeusz Sobolewicz, an Auschwitz survivor.)

Dr Maria Werkenthin

Janina Kowalczykowa

Participants of a nationwide TB congress in Zakopane in 1931. Dr Maria Werkenthin is sitting in the 4th row, on the left of an unidentified woman wearing glasses and a light blouse. Source: The National Digital Archives of Poland. Click the image to enlarge.

Dr Maria Werkenthin was born on 21 November 1901 in Podolia.67 Her father was the director of a sugar refinery. Maria’s grandfather was of German origin, and her mother was an Englishwoman, but Maria was born and grew up in Poland,68 and it was for Poland that she laid down her life. She died in Auschwitz in 1944.

Dr Werkenthin finished her school education in Kiev and went up to the University of Kiev for Medicine. She returned to Poland in 1922 and found herself in dire straits financially, so she had to take a job as a laboratory technician to continueher university education.

After graduating in Medicine, she worked as a radiologist specialising in pulmonary tuberculosis, the field of medicine to which she was true right to the end of her life. Her skills and persevering hard work made her an authority, both with practising physicians and in the world of science, albeit she did not go on to earn a further academic degree. The following passage comes from the fine obituary Professor Misiewicz69 wrote for Maria, which I have used for this biographical note:

Each of Dr Werkenthin’s works, whether a lecture she delivered or a published paper, is marked by the same characteristic features: a sense of responsibility for what she was saying, and a well-argued conclusion. She did not publish very much, just 12 papers, but each of them is a perfect clinical account. Professor Holzknecht70 of Vienna, whose working associate she was, considered her one of the best physicians he had worked with.

Very many physicians were ready to accept Dr Werkenthin’s medical opinions as absolutely reliable. She was characterised by a physician’s subtle intuition and a rare, innate talent.

Dr Werkenthin made a distinguished contribution to the professional training of pulmonologists specialising in the treatment of TB, and continued her activities in this field in clinical and radiological conferences even during the War under German occupation.

She was arrested for laying flowers on the grave of Home Army71 soldiers, and held in prison first in Łowicz andlater in the Pawiak jail in Warsaw, from where she was sent to Auschwitz.

She could have held a post of privilege in the camp and kept herself safe as a radiologist, or even survived, because there was a big demand for radiologists, who were needed for the mass sterilisation programme being done on women prisoners. But Dr Werkenthin kept quiet about her specialisation, not wanting to be involved in human experiments, and she worked in the dispensary, looking after her fellow prisoners.

In the summer of 1943 she contracted typhus, which left her with a nervous breakdown. She only responded to good news, which her companions made up to cheer her up.

One day, when one of Dr Werkenthin’s friendscame to see her and stood outside her block, she heard a German guard shouting, “Halt!” Right at that moment Maria was going down into the ditch that ran around the camp’s perimeter. Her friend started to run, but it was too late. When Maria tried to walk along the escarpment to get to the high-voltage fence, presumably in an attack of depression, to put an end to her life, the guard fired two shots. She was hit in the chest and died on the spot. On the same day a commission came from the main camp to investigate the incident.

For Dr Werkenthin’s friends it was a fatal accident and a great tragedy, because they all liked her, as she was fully dedicated to her work, which she had to do in such difficult conditions.

In tribute to Dr Maria Werkenthin, the Radiology Department of the Warsaw Tuberculosis Institute,72 where she had worked before the War, was named after her.

(Some of the information used in this biographical note comes from Stanisława Rachwałowa,73 Auschwitz survivor No. 26281.)

***

Translated from original article: Bystroń-Pytlik, Danuta, Denikiewicz, Władysław, et al. , “Sylwetki niektórych zmarłych polskich lekarzy i pracowników służby zdrowia zasłużonych w niesieniu pomocy więźniom Oświęcimia. ” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1961.

Notes

- Brzeszcze is a small place just 6. 8 km (4. 25 miles) away by road from the site of the main camp of Auschwitz, and half the distance from the Raisko sub-camp.

- Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, the Polish Socialist Party.

- Bataliony Chłopskie, the People’s Battalions, a Polish resistance organisation with combat units operating in rural areas.

- Armia Krajowa, the Home Army, the largest underground resistance movement operating in occupied Europe during the Second World War.

- Pomoc Więźniom Obozów Koncentracyjnych (Aid for Concentration Camp Prisoners).

- The resistance movement in and outside the camp developed a scheme to deliver medical parcels avoiding official inspection by addressing them to deceased prisoners. These parcels were them intercepted by prisoners in the resistance movement inside the camp who worked in the camp’s post office. See S. Kłodziński, “The contribution of the Polish medical profession to saving prisoners’ lives in Auschwitz”, on this website.

- Związek Byłych Więźniów Politycznych Hitlerowskich Więzień i Obozów Koncentracyjnych. Practically all Polish inmates held in the German concentration camps were political prisoners.

- Kęty is another local place, 20 km (12. 5 miles) away from Auschwitz main camp.

- Information given in this sentence, according to which the arrest of Prof. Gieszczykiewicz was related to the Nacht und Nebel, i. e. a 1941 directive from Hitler ordering secret elimination of political opponents, is not corroborated by the extant data and is probably simply incorrect. In fact, prof. Gieszczykiewicz was arrested in 1941 in Kraków within the framework of the Nazi German AB-Aktion (Außerordentliche Befriedungsaktion, i. e. , Extraordinary Operation of Pacification), an operation aiming at extermination of Poland’s intellectuals, including community, political, and religious leaders and officials, university professors and teachers at the various levels of the education system. Officially the AB-Aktion was launched on 30 March 1940 and was to last only a couple of months, but the actual arrests took more time than originally planned. Cf. Andrzej L. Sowa, “Państwo polskie i Polacy w drugiej wojnie światowej. ” Czesław Brzoza, Andrzej Len Sowa, Historia Polski 1918–1945, Kraków 2006, pp. 554–569.

- Docent—a postdoctoral academic appointment in some Central European universities.

- The City of Lwów was on Polish territory from the 14th century to 1772, and in 1918-1939. It now belongs to Ukraine and it known as L’viv.

- When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the Polish government instructed able-bodied men to join the Polish forces in the east of the country. But when Soviet forces invaded on 17 September, many returned home or fled abroad.

- In line with their racist policy, the Nazi German authorities occupying Poland closed down all the country’s universities, colleges, and secondary schools. Polish educationalists set up a system of secret university and grammar school education.

- Więzienie na ul. Montelupich, a large prison in the city of Kraków.

- Block 11, “Death Block, ” was the place where Auschwitz prisoners sentenced to death were sent for execution.

- SS-Hauptscharführer Gerhard Palitzsch (1917-1944). German war criminal. Conducted thousands of executions in Block 11. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerhard_Palitzsch.

- Główna Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, now part of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_Commission_for_the_Prosecution_of_Crimes_against_the_Polish_Nation.

- SS Dr Friedrich Entress (1914-1947). Nazi German war criminal, conducted experiments on Auschwitz prisoners. Pioneer of the “phenol jab” method of killing. Apprehended after the War, tried for war crimes, convicted, sentenced to death and hanged. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Entress.

- The inmates of Nazi German concentration camps were categorised into groups identified by different badges sewn onto their gear. “Political offenders” had a red triangle as their identification mark. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_concentration_camp_badge.

- Silesia is a region in a border zone between Poland, Germany, and the Czech Republic. Most of it now lies in Poland, but in the early 20th century it belonged to Germany and had a mixed ethnic population. On the restoration of Polish independence after the First World War, a plebiscite was held to determine the border demarcating Poland from Germany, followed by three anti-German risings by those Silesians who wanted to belong to Poland but found their area had been allocated to Germany. Under the Hitler regime and the occupation of Poland, the German authorities treated all native Silesians as German citizens; those who did not want German citizenship were penalised in various ways.

- “Gleiwitz” is the German name of the city of Gliwice (now in Poland), which belonged to Germany prior to 1945.

- “Breslau” is the German name of the city of Wrocław (now in Poland), which belonged to Germany prior to 1945.

- “Reichsdeutsche”—a Nazi term for persons holding “full” German citizenship, as opposed to “Volksdeutsche, ” persons with German roots but domiciled in countries under German occupation.

- In 1942, Heinrich Himmler ordered the deportation of all Roma to Auschwitz. As a result of this ruling, the Roma family camp known as the Zigeunerlager, which existed for 17 months, was set up in Auschwitz-Birkenau sector BIIe. Circa 23, 000 men, women, and children are estimated to have been imprisoned there. About 21, 000 died or were murdered in the gas chambers. Since they were treated as “asocial” prisoners, they were marked with black triangles. A series of camp numbers, prefaced with the letter Z, was given to them and tattooed on their left forearm. The Roma Camp was closed down on the night of 2 August 1944. That night at least 4, 000 men, women and children were killed in the gas chambers. http://auschwitz.org/en/history/categories-of-prisoners/sinti-and-roma-gypsies-in-auschwitz/.

- Tutaj (pronounced “tootay” is the Polish word for “here. ” The nickname would be pronounced “took-eye. ”

- On 3 May 1945 the Cap Arcona and three other German ships carrying concentration camp survivors were accidentally bombed and sunk by the Royal Air Force in the belief that fleeing Nazis were on board. https://theconversation.com/why-the-raf-destroyed-a-ship-with-4-500-concentration-camp-prisoners-on-board-75903.

- That is, five days before 9 May, the day on which Germany surrendered to the Soviet Union. It surrendered to the Western Allies on 8 May.

- Szpital św. Ludwika, a children’s hospital in Kraków.

- Władysław Bujak (1883-1969), Polish paediatrician. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/W%C5%82adys%C5%82aw_Bujak.

- Łańcut is a town 181 km (113 miles) east of Kraków.

- Powiat is the term for a second-tier territorial administrative division in Poland.

- Rabka is a spa and health resort 71 km (44 miles) south of Kraków in the mountain region of Poland. It is renowned for its sanatoria (especially for children) for the treatment of lung diseases.

- The Palace Hotel in Zakopane was a notorious Gestapo prison. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_(komisariat_Gestapo).

- Schwester Klara was a German midwife convicted for infanticide and sent to Auschwitz. See Stanisława Leszczyńska, “A midwife’s report from Auschwitz,” on this website.

- Original Polish title Dymy nad Birkenau (1st edition 145); English version Smoke Over Birkenau, translated by Jadwiga Rynas, (first edition Henry Holt: 1947). Available as an e-book online.

- This passage cited from the Polish edition has been translated by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa.

- Jan Glatzel (1888-1954), Polish surgeon, professor of the Jagiellonian University, active during the War in the Polish resistance movement.

- The habilitation is a post-doctoral degree awarded by some Central European universities. Scholars holding this degree used to be appointed docent (see comment 10).

- The Polish Underground State which operated in Occupied Poland during the Second World War had a domestic network of secret administrative, military and judicial agencies in contact with the Polish government-in-exile. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_Underground_State.

- Lecznica Związkowa and Dom Zdrowia.

- For more on Żelbet, see http://www.akgrot.wieliczka.eu/index.php?id=201 and http://www.kedyw.info/wiki/Andrzej_L._Sowa,_Krak%C3%B3w_pod_okupacj%C4%85_hitlerowsk%C4%85_-_stan_bada%C5%84.

- Józef Cyrankiewicz (1911-1989)—a prominent member of the PPS before the War, involved in the wartime underground resistance movement both at liberty and when held in Auschwitz. After the War Cyrankiwicz joined the PZPR (Communist) Party and served for many years as Prime Minister of People’s Poland.

- Konstanty Jagiełło (1916-1944). Polish Socialist Party activist. He and Tomasz Sobański escaped from Auschwitz; later he helped to organise other escapes, but was betrayed and killed in an abortive escape attempt. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Konstanty_Jagie%C5%82%C5%82o.

- Josef Meisel (1911-1993), Austrian Communist. https://de.zxc.wiki/wiki/Josef_Meisel.

- Marian Bomba (1897-1960). PPS member and underground resistance fighter during the War. Took part in the Żegota project to provide assistance to Jews. The incident in which Bomba was wounded is described in detail in S. Kłodziński’s biography of Dr Helena Szlapak on this website; see also https://krakow.ipn.gov.pl/pl4/aktualnosci/62746,Malopolscy-Bohaterowie-Niepodleglosci-Marian-Bomba-1897-1960-Pepeesiak-w-walkach.html.

- Gwardia Ludowa Polskiej Partii Socjalistycznej.

- See comment 26.

- Wanda Wasilewska (1905-1964). Writer and activist of the Polish and Soviet Communist Parties.

- Towarzystwo Uniwersytetu Robotniczego, a Socialist educational institution established in Poland in 1922. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Towarzystwo_Uniwersytetu_Robotniczego.

- Kazimierz Smoleń (1920-2012), Polish lawyer, Auschwitz and Mauthausen survivor, creator and director of the Auschwitz Museum. https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Kazimierz_Smole%C5%84.

- Dom Pomocy Społecznej im. L. I A. Helclów was founded in 1890 by Ludwik and Anna Helcel. During the Second World War the Germans requisitioned part of the building in 1939, and in 1941 they turned one of the wings into an annex of the Montelupich prison. https://www.dpshelclow.pl/historia-i-wsp%C3%B3%C5%82czesno%C5%9B%C4%87-w-domu-pomocy-spo%C5%82ecznej-im-l-i-helc%C3%B3w.

- The Fluchtpunkt was a badge prisoners suspected of attempting to escape had to wear on their gear.

- Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Union of Armed Struggle), one of the earliest Polish armed resistance organizations. Precursor of the Home Army (Armia Krajowa).

- Mentioned as “Jan Wozny” on p. 4-5 of the archival records of Genowefa “Pytia” Ułan (1908-1996), an underground resistance combatant. https://kpbc.umk.pl/Content/201548/Ulan_Genowefa_2894_WSK.pdf.

- Mentioned as “Egon Christiansen” on p. 4-5 of the archival records of Genowefa “Pytia” Ułan (1908-1996), an underground resistance combatant. https://kpbc. umk. pl/Content/201548/Ulan_Genowefa_2894_WSK.pdf. See also the statement of Stanisława Rachwał on the Chronicles of Terror site, https://www.zapisyterroru.pl/dlibra/show-content?id=3694&navq=aHR0cDovL3d3dy56YXBpc3l0ZXJyb3J1LnBsL2RsaWJyYS9yZXN1bHRzP2FjdGlvbj1BZHZhbmNlZFNlYXJjaEFjdGlvbiZ0eXBlPS0zJnNlYXJjaF9hdHRpZDE9NjQmc2VhcmNoX3ZhbHVlMT1EcmV6ZGVua28mcD0w&navref=MnY1OzJ1bQ&format_id=6.

- Muselmann (pl. Muselmänner), “Muslim. ” In the Auschwitz prisoners’ jargon, “Muslims” were prisoners whose physical and mental condition had deteriorated so much that they were on the verge of death. See Z. J. Ryn, “The rhythm of death in the concentration camp” (the subchapter on “The death of a Muselmann”) on this website.

- Rada Główna Opiekuńcza, the Main Council of Relief, the only Polish charity organisation recognised by the Germans in occupied Poland.

- Cf. the biography of Prof. Gieszczykiewicz above.

- Centrum Wyszkolenia Sanitarnego. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centrum_Wyszkolenia_Sanitarnego.

- Leitmeritz was the largest sub-camp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp. It was established on occupied Czech territory in March 1944, and Poles made up the largest group of its inmates. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leitmeritz_concentration_camp.

- The name is misspelled in the Polish text.

- See comment 23.

- Szpital Powiatowy w Tarnowie.

- Armia Krajowa (the Home Army); see comment 4.

- Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke GmbH, the German Equipment Works, a company which used slave labour from the concentration camps in its industrial plants. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Equipment_Works.

- Dr Stefan Pizło (1887-1942). See his biography on this website.

- Podolia is a region now in south-western Ukraine, but from 1568 until the late 18th century the whole of Podolia was in the Kingdom of Poland. From 1919 to 1939 the western part of Podolia belonged to the restored Polish State.

- Strictly speaking, Maria was born in the Russian Empire, as a fully independent Polish State was not restored until 1918. However, there was a large Polish community in the land of her birth.

- Prof. Janina Misiewicz (1893-1958), Polish pulmonologist specialising in the treatment of TB.

- Prof. Guido Holzknecht (1872-1931), Austrian radiologist. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guido_Holzknecht.

- See comment 4.

- Now known as Instytut Gruźlicy i Chorób Płuc w Warszawie (the Warsaw Institute for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases).

- Stanisława Rachwałowa (1906-1985), Polish counter-intelligence agent during the War, survived Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and Neustadt-Gleve concentration camps; after the War she engaged in anti-communist activities; was caught and sentenced to death in 1947 but later reprieved, released from prison in 1956. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanis%C5%82awa_Rachwa%C5%82owa.

Note 9 courtesy of Teresa Wontor-Cichy, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project. Remaining notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.