Author

Tadeusz Śnieszko, MD, physician, survivor of Auschwitz (prisoner No. 29620), and Ravensbrück. Follow the link to read his biography online on this website.

Alas, we are coming to write memorials for more and more of our colleagues and friends who survived the horrors of the War but are no longer with us. And so, Dr Leon Głogowski and Dr Tadeusz Szymański are two of those who have recently passed away. Dr Głogowski’s biography,1 written by Stanisław Kłodziński, is in the section dedicated to outstanding physicians in this edition of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. Readers of this journal may remember Dr Szymański as the author of an article entitled “Przypadki noma (rak wodny) w obozie cygańskim Oświęcim-Brzezinka”2 (Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1962: la, 68-78) and the co-author of the report “O «szpitalu» w obozie rodzinnym dla Cyganów w Oświęcimiu-Brzezince” (Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1965: 1, 90-99). Moreover, Dr Szymański wrote a biographical sketch of Dr Franciszek Gralla3 (Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1961: 1a, 77).

This issue of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim appears one and a half years after Dr Szymański’s death. I would like this obituary to perpetuate the memory of a dedicated physician, a man of integrity and trusty companion who shared the miserable fate of concentration camp prisoners. Dr Tadeusz Szymański was born on 13 January 1905 into a medical family in Skarżysko-Kamienna, where he attended school. In 1925 he completed his grammar school education and enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine of the Stephen Báthory University of Wilno,4 graduating in 1933. He completed his internship in the city’s municipal hospital. Next, he returned to his hometown to start his professional career. From 1934 to September 1939 he worked as a general practitioner in Skarżysko-Kamienna and as a company physician for a local activated charcoal plant.

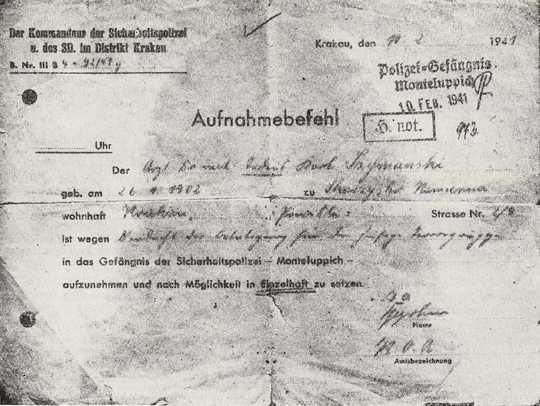

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, he was mobilised and took part in the September Campaign5 as a military physician. When the Polish defence collapsed he did not return to Skarżysko-Kamienna, as he did not want to work for the occupying army in its armaments industry. He left for Kraków and started working for the social insurance company as a substitute family physician. However, he did not enjoy this job for long and was arrested by the Gestapo on 12 February 1941, and jailed in the Montelupich prison in Kraków, on charges of belonging to the Polish resistance movement, or more precisely, to a “terrorist group,” as the arrest warrant said.

The warrant for Dr Szymański’s arrest, issued on 10 February 1941 by the commander of the Sicherheitsdienst (German Security Service) for Distrikt Krakau. Source: Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1971. Click the image to enlarge.

However, these allegations were not confirmed in the many hours of harassing interrogations and confrontations he was put through in the Gestapo headquarters and place of torture on ul. Pomorska (now ul. Wybickiego6). Yet it did not save Dr Szymański from being sent to Auschwitz. Its gate with the inscription Arbeit macht frei (Work sets you free) slammed shut for him on 5 April 1941. He was registered as number 11785.

Initially, it was dangerous for Auschwitz prisoners to admit to being a medical practitioner; it was better to pretend to be a craftsman or a labourer, which is what Dr Szymański did. Consequently, he was assigned to various work commandos and gradually lost all his strength, turning into a Muselmann.7 In the spring of 1942, when he reached a condition of extreme emaciation, he fell ill with pneumonia. After overcoming many problems, he was admitted to the prisoners’ hospital. There his constitution, still incredibly strong despite the debilitation, helped him combat the illness, but due to the typhus epidemic raging throughout the camp and the appalling level of lice infestation, he fell ill again and was moved to Block 20. For a long time, the prisoner-doctors did their best to treat his almost hopeless condition. Dr Szymański managed to overcome the critical phase and recovered. His appearance was pitiful; in fact, he did not resemble his old self, as he had lost over 40 kg (88 lbs.). His fellow inmates and friends could not recognise him. Yet, he slowly recuperated his strength and soon started working in the infectious diseases block, first as an ancillary, and from September 1942 as a nurse.

At the time the camp authorities did not formally acknowledge prisoner-doctors as “medical practitioners.” It was not until October 1942 that they began distinguishing between physicians and nurses. In late August 1942, Dr Szymański’s life was again endangered. To fight epidemic typhus, the SS decided to exterminate all the patients and staff of the infectious diseases block.

However, a couple of individuals who treated prisoners in a kinder manner intervened and it was decided to make a selection of those due to be saved out of all the prisoners in the block. Dr Szymański was fortunate enough to be in the group of 30 inmates who would later form the medical staff of the infectious diseases block. All the patients and most of the convalescents and functionaries – a total of around 800 people – were selected by the SS physician Dr Entress8 for the gas chambers and later their bodies were incinerated in the crematorium. A small group of convalescents and functionaries were sent to work in the commandos. The block was disinfected with the same Zyklon B9 gas that was used to kill prisoners. After the disinfection Dr Szymański returned to his block, which now accommodated patients from Block 13, i.e. the reserve hospital block. He was sent to work in Room 8 as a nurse and doctor.

He was dedicated to the sick entrusted to his care; he did his best to provide the best treatment for them, obtaining medications by any means available. To do this, he established contacts with inmates who worked outside the camp and could obtain the required medications from civilians and smuggle them into the camp. But administering medications was not enough; it was more important to provide patients with devoted care. Dr Szymański performed all the nursing duties very conscientiously; he did not shirk the unpleasant or troublesome jobs. He was always kind to everyone; his calmness and strength of mind encouraged inmates and gave them hope for survival and faith in a better future. Numerous sick prisoners owed him their survival and lives, as well as the chance to return to their families. One of the survivors whose life he saved aptly said that Dr Szymański always behaved like “a truly humane person.”

In late March 1943, he was moved to the Zigeunerfamilienlager, the Roma Family Camp in the new camp Birkenau, where he and other inmates were to set up a hospital. There were only two empty barracks (stables) with bunks for prospective patients; there was no medical equipment, not even the most primitive instruments, and most importantly, there was no running water.

Faced with such great difficulties, he proved his initiative. Together with other prisoner-doctors, he managed to “organise”10 medical instruments and some medications. In the camp jargon “organising” meant “try whatever and any way you like, as long as you don’t get into anyone’s bad books.” Then he had a water supply brought up to the hospital blocks. I can still remember how in the first days of our work we delivered babies attending women giving birth on simple planks on the barely levelled ground, in premises temporarily serving as a maternity room. Given such conditions, you could hardly dream of even the most rudimentary hygiene. Dr Szymański was appointed head of the block that served as a women’s and children’s ward.

The dreadful hygiene and food shortage filled the hospital blocks up at an alarming rate. Unfortunately, the results of the treatment we could give were very poor and the mortality rate was very high. The Roma people could not get used to the new conditions; their mental and physical resilience went down and they were prone to disease.

They contracted the typical camp diseases, such as diarrhoea, hunger oedema, and various types of skin infections in consequence of scabies, which was prevalent in the camp. The place was so lice-ridden that it was merely a matter of time for an epidemic of typhus to break out. Dr Szymański had to work in such dreadful conditions; he spared no effort to assist inmates although he realised that all the work he put in was futile.

The outbreak of typhus in the Roma camp meant that the two hospital blocks could not accommodate all the patients, so the authorities were forced to allocate more blocks to the hospital, giving a total of six, and assigning two of them to patients with infectious diseases. Dr Szymański became head of one of them, the women’s block. The working conditions were still deplorable, and all his superhuman efforts were to no avail. On average there were between 10 and 20 thousand Romani prisoners in the camp, but notwithstanding the constant influx of new transports, the figure was shrinking at an alarming rate, and nothing could stop it. By mid-May 1944, the number of inmates, including the sick, amounted to just around 7.5 thousand.11

In mid-July of the same year, by which time the authorities had decided to close down the camp,12 Dr Szymański and a dozen of his companions were sent to Mauthausen.13 There he was registered as number 80999 and sent to work in the prisoners’ hospital. Again the way he treated patients was full of compassion and patience. He gave them medical treatment, comforted and cared for them, in a word, he was their sincere friend, lifting them up, encouraging them to persevere and telling them that the end of their suffering was close at hand, and so was the longed-for day of liberation and freedom.

In March 1945, he was sent to the Floridsdorf sub-camp.14 There he faced even worse conditions; there was no question of any treatment whatsoever; all that he had available were paper dressings, to be applied only until the sick prisoner could stand up on his feet and still be able to work. If he turned out to be useless, he was immediately killed either in the gas chamber or with a petrol injection. Dr Szymański and another inmate decided to run away. They succeeded and were hiding in the Alpine forests until they were set free by the Soviet army.

After returning to Poland, Dr Szymański was completely exhausted by the hunger and illnesses he had gone through in the concentration camps and had to undergo medical treatment. Thanks to the help of his colleagues and the Polish Red Cross, he was slowly recuperating his strength, but he never made a full recovery to the condition he was in before his imprisonment. In February 1946, he took up an appointment as a general practitioner for the social insurance institution in Kraków. Starting on 1 February 1949, he was appointed to a number of management posts in the city’s municipal hospitals, proving to be an excellent organizer, a good colleague, as well as an understanding and equitable superior.

These posts, administrative rather than medical, did not give Dr Szymański much satisfaction in the long run. In fact, he wanted to continue his profession as a medical practitioner, constantly in touch with patients, so he resigned from his post as hospital director and took up an appointment as a company doctor in the outpatient clinic of a Kraków tin factory and as an internist in a specialist outpatient clinic.

In 1956, he was appointed head of the Jagiellonian University students’ outpatient clinic15 in Kraków. He was very enthusiastic about this job and soon earned the students’ trust and affection. He put in a lot of effort to provide them with better accommodation and food, especially for those who were in need. In 1962 he was awarded the Badge for Exemplary Service in Health Care.16 Unfortunately, the large number of his duties and the ordeals he had been through made him weaker and weaker, and finally he became seriously ill again. He had a heart attack and never recovered. He was ill practically all the time. During periods of relative improvement, he tried to continue working, but only for a significantly reduced number of hours. He was unable to give up his medical work. He wanted to keep on helping his patients, however little he could do for them, though he was seriously ill himself.

Finally, his body had no more strength left to battle against his incurable disease. His seemingly indefatigable constitution had to give in. The extremely heavy camp experiences must have produced a lethal effect. On 16 June 1969, Dr Tadeusz Szymański’s life came to an end. Our dear colleague passed away: he was a genuine patriot, an exemplary and conscientious physician and social activist, the author of an invaluable camp memoir, a great friend of all the sick, a truly humane person. Farewell, but stay in our memories forever.

***

Translated from original article: Śnieszko, T., “Dr Tadeusz Szymański.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1971.

Notes

- For the English version, see “Dr Leon Głogowski” on this website at https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/251071,dr-leon-glogowskia

- See the English version “Noma cases among the Roma in Auschwitz-Birkenau” on this website: https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/211091,noma-cases-among-the-roma-in-auschwitz-birkenaub

- Follow the link to read an article including Franciszek Gralla’s biography online on this website (Website Editor’s note).

- This city is now known as Vilnius and is the capital of Lithuania. Before the Second World War it was on Polish territory.a

- The Second World War started on 1 September 1939 when Germany invaded Poland. On 17 September 1939 the Soviet Union, Germany’s ally at the time, invaded Poland from the east. The Poles defended their country against the double invasion on their own for over a month. The period is sometimes referred to as “the September Campaign.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Invasion_of_Polanda

- Ulica Wybickiego was the name of the street from 1946 to 1981. It has now reverted to its original name, and the premises which once held the Gestapo headquarters in Kraków (at Pomorska 2) now accommodate a memorial museum. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulica_Pomorska_(oddzia%C5%82_Muzeum_Historycznego_Miasta_Krakowa)a

- Muselmann (pl. Muselmänner, “Muslim”). In the Auschwitz prisoners’ jargon, Muselmänner were prisoners whose physical and mental condition had deteriorated so much that they were on the verge of death. See Z.J. Ryn, “The rhythm of death in the concentration camp” (the sub-chapter on “The death of a Muselmann”) on this website.b

- Friedrich Entress (1914–1947), German war criminal. Served as a camp doctor in various concentration and extermination camps; in Auschwitz from 11 December 1941 to 21 October 1943. Conducted pseudo-medical experiments and was paid by the Bayer pharmaceutical subsidiary of IG Farben to test experimental drugs against typhus and tuberculosis. Pioneer of the phenol jab straight into the heart. This method enabled him to have up to 100 prisoners killed each day. Captured by the Allies in 1945, convicted and sentenced to death in the Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials, and executed in 1947. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedrich_Entressb

- Zyklon B was the trade name of a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid), as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such as diatomaceous earth. The product is notorious for its use by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust to murder approximately 1.1 million people in gas chambers installed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and other extermination camps. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zyklon_Bb

- In the concentration camp jargon, to “organise” something meant to procure it by fair means or foul (usually by stealing it).b

- At least 20,946 people (10,097 men and 10,849 women) were detained in the Sinti and Roma sub-camp in Birkenau. Source: APMA-B (Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum), główna księga ewidencyjna obozu cygańskiego (the main register book for the Roma and Sinti camp). Ref. no. D-AuII-3/1/1, D-AuII-3/2/1.c

- The Roma family camp was liquidated in early August 1944. About 2 thousand persons were moved to other parts of the camp, and the remainder, over 4 thousand men, women, and children, were killed in the gas chambers of Birkenau. Helena Kubica, “Children in Auschwitz,” Medical Review Auschwitz: Medicine behind the Barbed Wire Conference Proceedings 2018. Kraków: Medycyna Praktyczna, Polski Instytut Evidence-Based Medicine, 2019, p. 131.a

- Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp located near the Town of Mauthausen in Austria. About 190 thousand people were held in its main camp and sub-camps, and about 90 thousand of them died. https://www.mauthausen-memorial.org/en/History/The-Mauthausen-Concentration-Camp-19381945a

- Floridsdorf was a sub-camp of Mauthausen situated on the outskirts of Vienna. Its prisoners worked in the German armaments industry. https://www.mauthausen-guides.at/en/subcamp/satellite-camp-floridsdorfa

- Przychodnia dla Studentów Szkół Wyższych UJ.a

- Odznaka za Wzorową Pracę w Służbie Zdrowia.b

a—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—Translator’s notes; c—note courtesy of Teresa Wontor-Cichy, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project.

References

This brief biography of Dr Tadeusz Szymański is based on 1) my personal recollections of him; 2) information from Dr Szymański’s handwritten CV; and 3) a copy of his Auschwitz record card, which I received by courtesy of the Auschwitz State Museum.

A publication funded in 2020–2021 within the DIALOG Program of the Ministry of Education and Science in Poland.