Author

Stanisław Sterkowicz, MD, PhD, 1923–2011, cardiologist and historian of medicine, Neuengamme survivor.

Perhaps the most difficult issues of life and death during the Second World War arose in places that covered a small area but were extremely densely populated: the Nazi German extermination camps, surrounded by barbed wire fencing and rightly called by historians the greatest disgrace of the twentieth century. In those enormous mills of death, it was not only the body that was gradually degraded by exhausting labour and starvation, turning into a worthless physical object, but also the soul, which was stripped of all the ethical values normally respected in everyday personal relations. For in no other place did annihilation clash so strongly with the will to survive.

Survivors remember that time differently, because they experienced it in a variety of ways. The physical and mental aspects of that experience cannot be compared at any level since they depended on the environment in the particular camp, a person’s individual traits, the duration of their confinement, and their fellow prisoners. Therefore it is hardly feasible to produce an overall analysis on the basis of different survivors’ accounts, and although we have also amassed a large corpus of objective data and facts, some findings are bound to remain rather speculative.

I want to make these reservations at the outset so as to warn the reader not to extrapolate from the conclusions of this paper and also to emphasise that the subjective opinions which it draws on may be completely divergent, even if the two individuals giving them were incarcerated in the same camp in the same period. Every prisoner led a different life in this milieu and faced a different death, day in, day out.

My own remarks, which I have adjusted in line with my current medical knowledge, refer to Neuengamme, a concentration camp near Hamburg in the final stage of its operations in the spring of 1945, as well as to the time when I was held in a Gestapo jail in Berlin.

That jail was an interim place of detention for prisoners due to be relocated to particular concentration camps. The detainees were slave labourers1 who had been forcibly deported to Germany to work there. They were nationals of different countries and had been arrested for various offences: sometimes political, such as sabotage, distribution of the underground press or propaganda materials targeted against Germany; and sometimes criminal, such as stealing state-owned property for private use, or paraphilia. There were also cases of violating racial hygiene,2 but the most common offence was absconding from their workplace. The majority of the prisoners were of Slavonic origin and the largest group were the Russians. They proved the hardiest in the ghastly living conditions and were the quickest to adapt to the new environment. They also formed the most tightly bound community and were able to resolve several problems within it. We could clearly see that regardless of the situation, the Russians were well organised and self-disciplined, abiding by their own set of rules, which was not the case with other nationals. For instance, the Russians set up their own “courts” to deal with those inmates who had been proved guilty of stealing somebody else’s food. Those “trials” were held illicitly (so that the SS and Gestapo would not learn of them), but resembled regular court proceedings. Usually, the judges meted out physical punishments for offences against fellow prisoners and the verdicts were scrupulously enforced. For example, if the offender had stolen somebody’s food ration, they had to share part of their own ration with that prisoner until the loss was compensated. On the other hand, if a Russian prisoner was punished by the Germans by a reduction in their food rations for some period, their fellows were obliged to share a small proportion of their daily rations with them to keep them from becoming even more severely undernourished. To kill time, Russian prisoners locked up in the dungeon came up with different leisure activities, such as lectures, debates, discussing films, etc. Every group of Russian detainees, however small, had a leader; they were either the eldest of them, the best educated or the most senior in status. Such structures, arranged ad hoc, could not be observed in groups of prisoners of other nationalities.

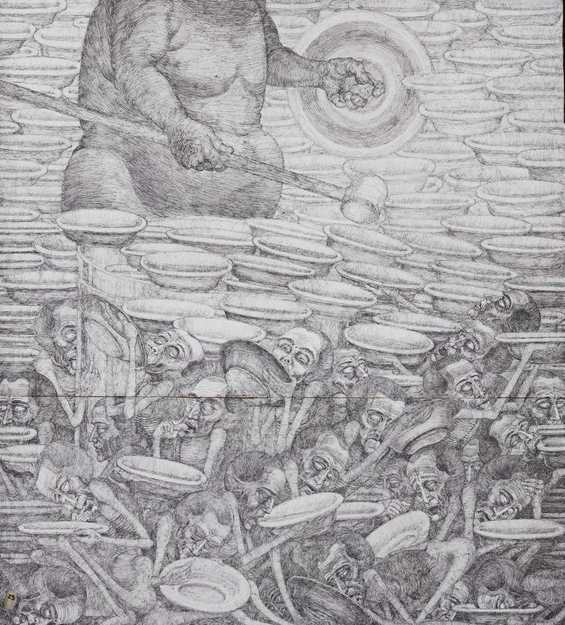

As prisoners grew more and more emaciated by starvation, their mentality underwent some changes too. As they had to scramble for survival, some features of their character came to the fore which, if it had not been for extreme hunger, would have never been revealed. For instance, fellow prisoners who sold food for a scrap of tobacco were looked upon with indifference. Tobacco was a prisoner’s trophy if they proved smart enough to be able to pick up a few cigarette butts during their workday. They could be used to buy a bowl of soup, a slice of bread, or a shirt with which a nicotine addict was ready to part. Food was the most valuable commodity both in jail and in the camp, and if you missed a meal, you suddenly found yourself standing at death’s door. Some prisoners lost their sense of solidarity, compassion, and friendship. The noble traits disappeared with the loss of integrity. The slicker or stronger would steal leftovers from other inmates and pleaded extenuating circumstances—the patriotic conduct for which they had been imprisoned in that hell on earth. Such incidents were not frequent, but memorable enough to leave every poor incarcerated creature with an impression that they were completely isolated and that there were no other sentient humans in the camp, which was chock-full of other inmates.

I suppose we shall never be able to say why some people who were able to stand the extreme hunger and the cruellest tortures at the hands of Nazi German tormentors, which were much more painful than hunger, could forget about self-denial and self-sacrifice when facing their fellow inmates. Very few prisoners were ready to turn sycophants to the butchers or accept the jobs of functionaries for the price of food. Yet it was for the sake of food that they could prove ruthless, merciless, unconcerned, and heartless towards those who lived next to them, but whom they expected to die first. I don’t think that anyone who wasn’t there can today honestly say they know the nature of the human soul or that they know their own worth. It is easy to be good in propitious circumstances, but much less so in the face of death. People’s altruism burst like a bubble when confronted with the complexity and horror of life in the camp. The lesson to be learned by a human being was as follows: “It will be better if I eat your slice of bread instead of you having it. If I do that, I will increase my odds of surviving. And I don’t care what’s going to happen to you.”

Though theoretically equipped with higher order emotions, detainees were terribly brutal, callous, and insensitive. Where were the limits to this bestiality, given that it was not so rare and exceptional to come across cases of cannibalism, as some prisoners preyed on dead bodies, or mugging, as Muselmänner3 were robbed of their morsels of food? Is a slice of bread a bitter limit to our elemental goodness?4

When we were still in jail, almost every prisoner wanted to be relocated and transferred to a concentration camp as soon as possible. It seemed that not being interrogated by the Gestapo as well as working outdoors, where it was possible to procure more food, having more freedom than in a prison cell and more opportunities to interact with many fellow inmates could make life more bearable. Undoubtedly, those expectations were fulfilled for some of us, but a reservation has to be voiced here: although the caloric value of the food rations was slightly better in the camp, the exhausting work soon turned prisoners into human wrecks, and the process was quicker than during sedentary incarceration in jail. Even though the conditions in jails and concentration camps were different, the adaptation took a similar course. How well a person adapted to the environment depended on a variety of factors: being quartered in a better residential block, supervised by a more lenient Blockleiter;5 the time when you arrived in the camp; the work that you were assigned to do; and primarily your individual traits. The final stages of the War were marked by extremely intense extermination, so only the strongest and the smartest of those who were deported to the camp at that time could survive. The rest never adapted to living in the camp, because they simply died before they could adapt. Only those who were physically and mentally tough could hold out. In that group of prisoners, the feeling of compassion vanished quickly. It faded away minute by minute, as swiftly as your strength. A prisoner who managed to lay their hands on an extra morsel of food would often hide away in the darkest corner to devour it in the bat of an eye. There was something animal-like in how they fled the plaintive glances of their fellows. When the higher emotions had disappeared, they were superseded by the wilder, animal instincts which arouse horror. A Muselmann got no pity nor even any understanding from a stronger prisoner. When some emaciated creature collected potato peelings, rotten swede, and machine grease, and having eaten them, got bloody diarrhoea and died, a stronger prisoner would say, “It served them right. Why did they eat that gunk?” When a Muselmann was willing to sell their food for a pinch of tobacco, a less wasted prisoner would buy it, saying that it was a fair deal and they should not be blamed for somebody else’s stupidity. In that terrifying jungle of instincts, there was just one, primeval law: “Only a strong person has the right to live.”

Starvation is another topic in the history of Nazi German concentration camps during the Second World War. It has been discussed on many occasions, both in fiction and in sociological or historical studies. Hunger disease in concentration camp prisoners is perhaps a unique phenomenon in the history of mankind. All that prisoners ever talked and thought about was how to satisfy their perpetual hunger. Working out simple as well as unconventional methods to do that was the single most important objective of each day. It all started in the morning, when prisoners had to form rows of five before they marched out to town. Everybody strove to take a place on the flank of the column in order to be able to scavenge for food in the gutter or the waste bins on the sides of the streets. A bin was a prisoner’s El Dorado, where they could prospect for more or less appetizing leavings of food. Potato, swede, and carrot peelings, a mouldy old fish head, a speck of lubricant, and spilled grain were coveted trophies. Those who were not so badly undernourished could put any food they scavenged “on the market” before the evening roll call. It stood to reason that you should not eat bad food so as not to become gravely ill and even weaker, but the animal instinct took over and told you it was necessary to alleviate pangs of hunger at least for a moment. Acting on that instinct quickly turned a prisoner into a Muselmann, prostrate and oblivious to the world.

It is quite thought-provoking to realize that regardless of the continuous struggle for survival, the fear of death a prisoner had felt before retreated as their strength dwindled away. In a person who was growing weaker and weaker, death no longer inspired fear and later turned into the only saving force able to spare them the great torment which otherwise would have been inescapable. If they still felt any fear, it was not of death, but of the pain that could have been dealt out to them by their torturers before he expired. But even that last fear diminished with the progress of cachexia. The physical pain inflicted on them no longer hurt them and the mental pain became vague and distant. When a person reached this condition, death seized them imperceptibly.

Curiously from the medical point of view, although Muselmänner were extremely emaciated and had lost a lot of their protein tissue, they had no starvation oedemas typical of hunger disease. Many Muselmänner only developed oedemas once they started to convalesce, sometimes after liberation. However, that symptom was not observed everywhere (because in other camps debilitated prisoners suffered from oedemas).

To satisfy hunger was the greatest obsession, more urgent than any other desire. There was no prisoner who was unwilling to take revenge on their oppressors, yet when they were given back their freedom, they first went to the storage rooms in order to get food in a sufficient, unlimited, unrationed quantity. Revenge could wait for later. On a chilly April night, horrific scenes unfolded in Sandbostel POW camp, where the few survivors of Neuengamme found shelter. The SS men who had escorted Neuengamme prisoners to Sandbostel wanted to leave, fearing unavoidable retribution from their victims. News of their departure quickly reached the barracks. Thousands of prisoners rushed out into the yards, which were empty at night, and stormed the kitchens and storage rooms. The SS men thought that the attack was targeted at them and opened machine gun fire to forestall it. However, nothing could stop the multitude who felt they were about to be liberated. As hunters cannot stop a pack of hungry wolves by shooting at them, so the SS cudgels could not deter the crowds raiding the stockrooms once the doors were broken down. Prisoners also barged into the kitchens. Darkness hid indescribable events. Those who fell in the stampede were trampled and kept groaning. The crowd pushed forward and scuffled over food, agitated and swarming in the dead of night. They elbowed their way forward in order to get hold of precious bread, flour, sugar, and tinned food. Those who did not get to those goodies went for the soup left in the vats. In the small hours, a few bodies were discovered in them: these prisoners had drowned in those macabre circumstances and never saw the dawn of freedom. They paid the highest price to relieve their hunger.

Following liberation, a large number of Muselmänner were transported to military field hospitals. There they were treated for extreme exhaustion, often with comorbid chronic and severe dysentery. In many cases the treatment proved unsuccessful. Some survivors resorted to self-treatment, which was nothing less than abstaining from food for a few days. Many of them were unable to follow this starvation diet. The first day left some of the sick completely indifferent to the world. After the second day, the need to eat disappeared. Finally, an aversion to food developed, which was a bad omen. Sometimes the diarrhoea stopped, but the sick person had grown so weak that they died. So the treatment was successful, but the patients did not survive. Those few doctors who tried parenteral nutrition and hydration to save the lives of the people in their care often worked in vain. In the majority of cases, their patients died on the threshold of freedom, unable to manage even a weak smile of happiness. The winners died unaware of the fact that they had won.

For many years to come, survivors continued to have dreams about being able to fill their stomach. The military hospitals, which took in the most severely sick, attempted to help them to develop and gradually adopt normal living and feeding routines. The caloric intake they provided was sufficient, but for obvious reasons meals had to be small though frequent. Many survivors protested, saying that again they were receiving far from adequate, starvation rations. Paradoxically, some even claimed that the camp food had been better: when you had a litre of soup, you felt sated at least for a moment, which did not happen in the hospital. Driven by the nagging sense of hunger, convalescents would venture out of the wards to get more food. Sometimes there were serious consequences of such forays and in a few cases the end result was death. To prevent accidents of this sort, the medical authorities prohibited patients from leaving the premises and set up checkpoints around the hospital grounds. These slightly unconventional regulations saved the lives of many starvelings who wanted to procure extra provisions both for themselves and their fellows.

One of the biggest enigmas that require some medical research was the fact that although survivors were exhausted, they were also remarkably vigorous compared to their state of debilitation. Only a few days before liberation, thousands of prisoners looking like a bag of bones in striped gear were still marching out from the camp to different workplaces to perform extremely hard labour. It is puzzling how all those people managed to find enough strength to do that when in fact they were generally unresponsive and apathetic. Just before liberation, when the SS personnel knew Allied troops were near, many prisoners experienced a crisis though they were no longer expected to work. Practically overnight, thousands of people who used to be able to walk long distances and shovel mountains of sand while being rushed and whipped by a yelling SS man, turned incapable of any physical effort at all. The camp looked like a battlefield full of wreckage. This was a common phenomenon and may perhaps be rationalised only in the following way: when an individual was fighting for survival, they were driven by some inner forces which we know very little about but which constantly kept them ready to put up with any blows they were about to suffer. Even though their strength was depleted, these stimuli gave them the will to continue the struggle. Perhaps that is why, mysteriously, so many prisoners held out, although, if we come to think about it, they should definitely have died. Those forces activated some extra reserves and operated in the entire body, giving a surprisingly good effect. They increased prisoners’ chances of survival. Those unknown and still unidentified inner forces could be compared to the resistance described by Filatov6 in his famous theory; they acted like stimulants some athletes use to reduce tiredness and build up stamina. However, you cannot cheat Nature, and experience shows that there is always a high price to pay for doping. There have been fatalities due to doping in sports, no wonder then that breakdowns and deaths also occurred after prolonged periods of “inner doping.” The real condition of an individual’s body was revealed once those life-sustaining forces stopped working.

This is probably why multitudes of people inured to a daily struggle for survival suddenly broke down. With no “inner doping,” they turned into the living dead, with just a faint glimmer of life in them. From the point of view of medicine, such phenomena, which have not been seen on such a large scale so far, are an interesting research subject. They suggest that when a human body goes through long and intense stress, it may produce some yet undiscovered substances which give it the strength for the ultimate struggle. If we were able to confirm these facts and explain them in a scientific manner, we would gain new arguments to support Filatov’s theory. I am not saying that this interpretation of these phenomena (which really occurred, as I can assert as a survivor and as a person who experienced them) is the only possible or correct one. As no other explanation is available, I present my own, because I think it offers a logical justification of what was manifested as well as new observations on the way haplorhines die if they have been kept in unpropitious conditions over an extensive period.

The Allied victory over Germany closed a gloomy chapter in the history of humankind, a chapter written by the Übermenschen, the Nazi Praetorian Guard. Having recovered their freedom, survivors quickly regained their joy of life and ceased to exhibit certain character traits they had during their imprisonment. They gave up indifference and hatred and were able to share their assets with their fellows. Again they knew how to be noble, honest, selfless, charitable, that is they followed the conduct that is embraced by the term “higher order emotions.” To put it briefly, those who had been hounded to death became normal again.

However, something remained in the minds of all those people who had lived through the hell of the concentration camp. Nowadays, that something may resurge in their memories at the most unexpected of times, demonstrating that human beings are still an unsolved mystery. Their behaviour in a familiar and healthy environment is logical and absolutely comprehensible. Yet in an abnormal milieu, they are able to take the plunge and respond in ways that may never be understandable and intelligible.

Why was it that millions of Germans were able to murder millions of innocent and powerless people with such sadistic joy? Why did a slice of bread mark the limit to a harassed person’s goodness and integrity? Why did civilised individuals commit acts of cannibalism on the bodies of their dead fellows? Who is going to answer all those questions that require a reply for us to learn the truth about how we are able to live, fight, and die in conditions of utmost humiliation?

***

Translated from original article: Sterkowicz, Stanisław. “Obozowe sprawy życia i śmierci w retrospekcji lekarza.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1963.

Notes

- During the Second World War, Nazi Germany operated a system of slave labour in the countries it occupied, forcibly deporting their inhabitants to work in Germany. The German authorities occupying Poland caught people who happened to be out on the streets in round-ups and sent them to Germany for slave labour. About 2 million Polish citizens are estimated to have suffered this fate. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forced_labour_under_German_rule_during_World_War_II a

- Rassenschande (“race defilement”) was a concept introduced by the Nazi German propaganda in early 1935. It grew in importance after the Nuremberg Laws were passed on 15 September 1935, legalising and propagating discrimination against the Jewish people, which was an important point in the racial policy of the Third Reich. b

- Muselmann (pl. Muselmänner) was the term in German concentration camps for the extreme stage of starvation disease, when all the victim’s defence mechanisms degenerated into a state of atrophy, their sense of hunger and pain disappeared, and their body teetered on the edge between life and death. a

- Dr Sterkowicz’s remarks are based on his incarceration in a relatively small, but very severe camp, where he was held for several months. It has to be stressed, and this has been done in the introduction (to the original issue of Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim), that this “bitter limit,” beyond which man turned into a beast, was crossed only by some prisoners. c

- In a German concentration camp, the Blockleiter (block leader) was the functionary responsible for order in a particular prisoners’ residential block. a

- The Filatov family produced several eminent physicians who worked in the Russian Empire and later in the Soviet Union. They included the paediatrician Nil Fyodorovich (1847–1902), the ophthalmologist Vladimir Petrovich (1875–1956), and the zoologist and embryologist Dmitriy Petrovich (1876–1943). d

a—notes by a, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Maria Ciesielska, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; c—original Editor’s note; d—note by Marta Kapera, the translator of the article.

References

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

The contents of this site reflect the views held by the authors and do not constitute the official position of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.