Author

Seweryna Szmaglewska, MA, 1916–1992, Auschwitz survivor (No. 22090), psychologist, writer, educator. During the Nazi German occupation of Poland volunteered as nurse and was involved in clandestine education system, as well in the resistance movement.

Arrested and sent to Auschwitz in 1942, she survived almost three years in the concentration camp and then managed to escape from one of evacuation transports in 1945. Szmaglewska was one of the witnesses called upon by the International Tribunal in Nuremberg to testify in 1946. She is the author of one of the first major personal non-fiction books about the experience of Auschwitz, Smoke over Birkenau, a widely read and translated work praised for both its accuracy and literary merit.

Read more:

A talk given during an official session of the Kraków Branch of the Polish Medical Society on January 23, 1963, on the 18th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp [original Editor’s note].

Dr Stefania Kościuszko,1 petite and starved so thin you could almost see through her, climbs up to a top bunk bed in Block 24, Camp A. The triple bunk is packed chock-full with sick inmates—two or three women lying next to each other, all running a fever. Suffering from tuberculosis, arthritis, infectious bloody diarrhea, or malaria. Next to the bunk, parallel to the roof line, there is a horizontal opening, a dozen or so centimeters high, running around the entire barrack. Dr Kościuszko can see part of the camp through this chink. When the wind blows from the north or south, snow falls on the blankets covering the inmates and melts on their hair and faces, like a chilling cloak of death on creatures still alive. A typhus epidemic is wreaking havoc in the entire camp.

Their body temperature is thirty-nine or forty degrees Centigrade.2 They’re unconscious. Many contract meningitis; some go insane. During the night, a mischief of rats scampers over the quick and the dead. Starvation reigns supreme—you don’t see food or clothes parcels even in your dreams. There’s no water. The blankets are full of insect nests. Unconscious inmates have no strength to fight for better hygiene conditions in the barrack, which is not heated: a brick stove has not been built yet.

When I think about it now, I find it hard to understand and explain how it happened that a certain percentage of sick prisoners managed to survive, especially as they could not count on anyone’s help: their deaths seemed to be just a matter of time. And they did die on a mass scale.

Was any medical assistance available in those conditions? What could Dr Kościuszko bring to sick inmates when she diligently visited them during her daily rounds in the prisoners’ hospital? Sometimes all she could do was to take an aspirin pill out of her pocket. One pill a day or for a longer time. Usually, she did not bring anything. But even then, she used to see the sick, look calmly into their eyes, trying to find any signs that they were still conscious. She took their pulse, put her ear to their chest. She said a few words to her patient, nothing sensational, but her visits were of colossal importance. In 1942, during that early period of the camp’s existence, this was all that the health service in Auschwitz was. That winter, the role of prisoner doctors was to see patients as regularly as possible, mainly in the late evening after the last roll call.

They asked sick inmates how they were doing. Every prisoner who survived Auschwitz in a decent way knows very well how hard it was to find any energy and some free time in the murderous routine of the day: running to work, running to the roll calls, like animals struggling to survive.

Today the horror of Auschwitz does not mean the same to all the people in our country. So, as I present these biographical notes on prisoner doctors who will always live in our memory (not all of them survived)—I would like to say a few simple but unpopular words: those prisoner doctors had great moral strength, the great moral power they needed to offer heartfelt medical care, from beginning to end, in the cogs of the machine that crushed people up long before they died; moral strength in the face of genocide and violence from depraved camp functionaries.

Some people in Auschwitz lost control of the morality of their conduct. They fell into a kind of nightmare, letting their lives follow the line of least resistance. For many, the line of least resistance meant survival at the expense of others. That was the background to the work of tiny, pale Dr Stefania Kościuszko calmly, generously and conscientiously performing her medical duties at a time of ravaging epidemics. I often think about her. All I can say about her boils down to a short phrase: her memory lives on.

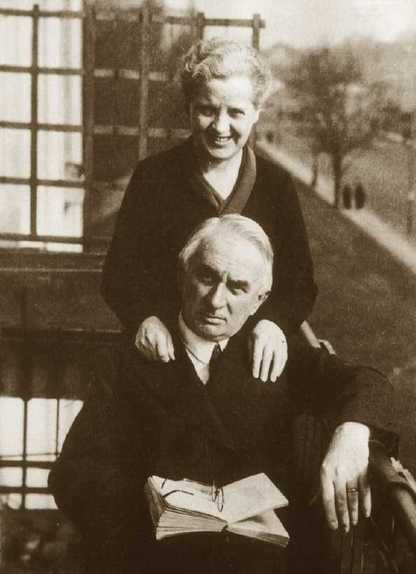

Zofia Garlicka and her husband in their home garden at No. 8, ul. Topolowa (now No. 216, Al. Niepodległości) in Warsaw. Source: Ciesielska, Maria, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-1945). Click the image to enlarge.

I had known Dr Garlicka3 for a few days but I did not realize she was a prisoner doctor. I can still remember her figure on that chilly October morning. A gentle giant bending over a potato she was peeling, smiling and from time to time casting joyful glances at her neighbor. She had just gotten a job peeling potatoes. An outdoor job, but under a roof. For the past few days her back was no longer being pelted by the sleet and snow of the fall season; she would not be ordered to carry rails for a narrow-gauge track nor to load up its freight cars with sand and gravel. Her fingers, which had gone blue with cold, twirled a potato round and again she looked at her neighbor. At the time, I did not know that her daughter, Zofia Jankowska, was also a prisoner in Auschwitz. Someone came running into the potato room. There were nervous whispers, and suddenly this big woman, with a rag instead of an apron on her and stiff fingers covered with a crust of dirt, jumped to her feet. She could not walk properly in those clogs that kept falling off her feet; her movements were clumsy and she was hunched more than usual. She followed the woman who had called her, asking her neighbor and me (why me?) to come along with her. I got the picture once we reached an empty barrack. There was a young girl in it, curled up between the bunks and writhing in pain. We stood on either side of the door. Now I could see that this big woman was a doctor. She examined the girl quickly and efficiently, every second was valuable; her actions and thinking were quick, Dr Garlicka’s many years of experience helped her diagnose the patient. Now, at least for this short moment, she had recovered the right to practice in her profession and apply her knowledge; she had recovered her identity, and the sick prisoner needed her. The block leader gave her a gentle signal, a barely audible buzz. We had to finish and leave immediately, yet for a short spell Dr Garlicka was not a prisoner peeling potatoes but a physician. So she calmly gave her professional advice to the nervous block leader, repeating her medical recommendations and explaining them in detail. When the SS block leader was about to leave, Garlicka said to the sick girl, “I’ll be back in the evening.” How many times did she say that goodbye to sick inmates to give them hope? Hope that meant so much to them, that everything would be fine since someone was looking after them and would visit them again on the same day.

Zofia Garlicka Source: Ciesielska, Maria, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-1945). Click the image to enlarge.

A few days later, the new potato team was brought down by fever. I saw Dr Garlicka in Block 24; she was not well, her eyes looked lifeless. She climbed up to my top bed in the triple bunk, just under the roof of the barrack. She gave me a smile, signaling her decision: “I’m staying here and sleeping next to my daughter. I’ve been through epidemic typhus, so I don’t think I’ll catch paratyphoid. My daughter will feel a little better and more cheerful with me around.” Maybe her words were an answer to some of my questions, or maybe it was the way she fought off her own doubts. My eyes followed her. I could see her tall figure between the triple bunks that looked like wooden scaffolds, making her way to the opposite side of the barrack, then climbing up to her bed, where the blizzards came in if there was a north wind. So we had Dr Garlicka with us day and night, always ready in an emergency, on call all the time. She did the duties of an orderly or a nurse more often than those of a doctor. Then she developed a high temperature. “It’s flu,” she told us and continued to perform her usual work. Then both she and I were in a critical condition. After many days and nights of struggling with darkness, I finally regained consciousness and learned that Dr Garlicka’s daughter had died, and that the doctor had passed away the previous day.

I don’t know the name of the prisoner doctor who was an ophthalmologist and came in twice a week from the men’s camp to the hospital in the women’s camp. I have no idea if he’s still alive now. I never had the chance to thank him although he probably saved my sight or even my life. He examined the eyes of the women prisoners crowded in front of him and hurried because he only had a limited amount of time. He applied drops, silver nitrate, or an ointment, and put us down for another visit. For many weeks in the fall of 1943, my fellow inmates from Camp B used to bring me in blindfolded to the outpatient room in Camp A. I wanted to save my eyesight. Corneal ulcers cause unbelievable pain; a patient with such pain can experience a breakdown if left to themself. In the concentration camp, visits to the prisoners’ hospital certainly had an additional purpose: the doctor’s professional words strengthened the patients’ faith in their chance to recover their sight, which would put them on the way back to the world of the living. I don’t know who this prisoner doctor was and whether the great silence of Auschwitz closed up over him, as it did over millions of prisoners murdered there.

I got to know Dr Węgierska4 first as a voice in the dark, speaking harshly or perhaps just with a bit of verve. Under cover of the night, she went from one bunk to another, helping women who tried to beat their illness without going to the prisoners’ hospital, where they could face selection and death. In the morning, these sick inmates went to work and needed all the strength they could muster to attend roll calls. When I heard her voice over me and she had finished her conversation with another sick inmate, I reached out and grabbed the hem of Dr Węgierska’s robe. Holding on as fast as I could to the hope which had dawned in the dark, I told her about the troublesome effects of my neighbor’s typhus. Dr Węgierska patiently and professionally instructed me what to do, what methods of treatment to use to fight off this obstinate and dangerous disease without medications, because there were no medications available in Auschwitz at the time. She came to us again several nights later. This time, I did not have to call her as she leaned over the lower bunk and asked, “How are you, a little better?” “A little bit better,” replied my neighbor, struggling to control her pain.

And again we heard the same energetic voice, “Carry on in the same way. Don’t stop. When you get herbal tea for the evening meal, massage your belly with the hot pot. Char the crusts of your bread and eat them.” That was all the therapy given the conditions in the camp. This example of advice shows the chances for the provision of medical care in the camp, especially in its early period, when prisoners had no access to medications. Months passed. I saw Dr Węgierska attending patients, stubbornly struggling to save their lives. But to me, the way I will always remember her, she was a voice in the dark.

I remember another incident from Auschwitz.

Władysława Jasińska. Source: Ciesielska, Maria, Szpital obozowy dla kobiet w KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-1945). Click the image to enlarge.

Dr Jasińska5 was doing an autohemotherapy in broad daylight, in the middle of Hospital Barrack 23 on a patient covered with ulcers. The needle was in the vein and blood was steadily and slowly rising in the syringe. Suddenly there was a loud bang on the door. An SS man burst in but stopped in the doorway, finishing a conversation with someone; so he was standing sideways to the doctor. Dr Jasińska went pale. Her fingers were trembling. Blood was trickling down onto the dirt floor in the barrack. It was just a matter of seconds before the SS man turned his back in his tight-fitting German uniform, and it was all over and the situation was under control. The doctor told a patient to clean the room up. Things were back to normal in the hospital block. It wasn’t until a few minutes later after the SS man had gone that Dr Jasińska finished the treatment. She didn’t have any medications, so she used syringes to treat concentration camp phlegmons.

At first, I had a deep grudge against Dr Zbożeń6 because on a December morning in 1942, he discharged a group of inmates from the hospital. In my opinion, they hadn’t reached the convalescent stage yet. He sent them back to their blocks, and then they were ordered to line up in columns and go out to work in the fields; it was Aussenarbeit (an outdoor job), breaking up the frozen ground with a pickaxe or a spade.

It was undoubtedly a spell of convalescence as hard as their previous weeks of being ill with typhus. At the time I did not know the camp policy and what the words “hospital selection” meant. But Dr Zbożeń did.

So he was determined not to use the term “typhus.” With a cheerful smile, he spoke of flu and kept a record in his notebook of cases of flu and spoke to his patients of flu. Flu was not serious, a disease which in the Nazi German system did not require the sick prisoner’s extermination. It was only much later, once I had learned the “secrets” of Auschwitz and understood the meaning of the term Vernichtungslager,7 that it was just a matter of seconds to walk from the living to the side of the crematorium and wait for imminent death. Then I realized Dr Zbożeń had insisted on the right decision.

In February 1943, when the hospital began to grow as a result of the rising number of patients, I met Zdenka,8 a Czech prisoner doctor, on the first day of her work in the hospital.

She looked worse than any of the cleaners. She was wearing prison gear that looked like a baggy sack and wooden clogs that made it difficult for her to walk, and she often blushed with shame when she had to give orders to the nurses. She had just arrived in the camp, so you could see she was in dire straits, coming up against problems all the time. But she still managed to run Block 17, making it a haven of peace and quiet. She knew how to protect sick and convalescent inmates and allowed them to stay in the hospital for two or three days longer than they had a right to officially. Yet it was a superficial tranquility: at night you could hear insane inmates howling and screaming. They were women suffering from mental disorders which they had developed as side effects of typhus, and were sent to this block from all over the camp. One day, the screaming suddenly stopped. Instead, the horrid, tangled pile of naked corpses behind the gate of the barrack grew larger. The dead had their mouths open in their last scream and their fingers were bent like claws trying to hold on to their lives.

In the following years, 1943-44, the typhus epidemic damped down for several weeks or even months, and then attacked again with redoubled force. Although the hospital gradually expanded to include new barracks, still there was not enough room for patients; often they had to lie three or four abed, covered with one blanket stiff with dirt.

In such conditions, the struggle to survive was a hopeless battle, doomed to failure from the start. In the fall and winter of 1943/1944, the average death rate for both of the women’s camps was three hundred a day. Of course, this figure does not include selections in the hospital and throughout the camp.

The prisoner doctors did not give up. On the contrary, they started to work in an organized manner, trying to keep in touch with colleagues in other camps, obtaining medications, performing complicated operations. Also, they did their best to mislead the Nazi Germans to save prisoners’ lives, which was risky and highly dangerous.

I remember Dr Łaniewska9 and the difficult and hopeless war she was waging at the time. The more and more intensive efforts prisoner doctors were making seemed to be coming up against multiple, aggravated forms and variants of disease: from hydrops, which turns the human body into a white balloon practically devoid of its facial features; through numbness of the neck, which soon killed off its victims; all types of tuberculosis, phlegmons giving rise to general infection; through lice infesting every prisoner straight on their first night in the camp; and inevitably to typhus and its effects. Against this background, from time to time there were births and a new life began, sometimes lasting only a few hours or, in a few cases, saved from Nazi German atrocity.

For each of us inmates, our paths were solitary and different. We experienced what has come to be known in world history as “Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.” Our decisions were taken in solitude: how to live, how to treat others and ourselves, from what sources, whether in full awareness or not, to draw that surplus of strength we needed to behave like humans and still survive in the inhuman world of Auschwitz. Even the most socially oriented of us, inspired by an idea and keeping up each other’s faith in the purposefulness of going through this jungle decently with our hands clean—we all had to make these choices on our own and bear the consequences. The paths of the prisoner doctors of Auschwitz were the steepest, most dangerous, and precarious.

This great chapter in Polish medicine is slowly being filled in with books and records of everlasting value. Prisoner doctors’ diaries are gradually being published; the whole of society is waiting for them. The story of these doctors can be told only by those who knew them best.

The statement I am making today is neither complete nor exhaustive. It does not give the names of many prisoner doctors, nor does it claim to be anything more than it really is. It is meant as a tribute to all the health service workers, to those who died in the camp and those who survived and are with us today. They put up heroic resistance to Nazism, building a kind of rampart, one of the most important barricades blocking the way for genocide.

Finally, I would like to warmly thank the organizers of today’s session for giving me the floor. Also, I would like to pay tribute to those who are systematically and jointly continuing to work on a great issue, or rather a set of issues labeled “The Health Service during World War II.”

***

Translated from original article: Szmaglewska, Seweryna. “Sylwetki lekarzy-więźniów Oświęcimia.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim, 1964.

Notes

- Stefania Jadwiga Kościuszko (1893–1943). Sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 27, 1942, and registered as No. 11987. Died in Birkenau on January 11, 1943, having contracted starvation diarrhea and suffering from frostbite, abscesses, and erysipelas.

Stefania Kościuszko was born on December 21, 1893, in Jasło, to Piotr Kościuszko and his wife Aniela née Kozowa. She attended school and completed her secondary education in Jasło, and went up to the Jagiellonian University to read Medicine, graduating in 1924. Her first appointment was in St. Louis’ Children’s Hospital, Kraków, where she worked as an assistant physician in Professor Bujak’s ward. On qualifying as a specialist pediatrician, she moved to Łańcut, where she set up the city’s first TB clinic and equipped it with an X-ray machine from her husband. After her husband’s death, she moved to the health resort Rabka Zdrój and worked as a children’s doctor in a convalescence home for army officers and had a private surgery in Władysław Kołaczek’s house on ulica Poniatowskiego. She also ran a boarding school for children with TB, financed by Poland’s national health insurance company. When Nazi Germany invaded Poland and started the Second World War, many of the doctors in Rabka joined the resistance movement, and Dr Stefania Kościuszko was one of them, operating as Biala or Jadwiga and organizing health services for members of the resistance. Her apartment was used as a venue for secret meetings and a distribution point for the underground press. On June 26, 1942 she and other members of the resistance were arrested after being denounced by Lt. Michał Brzoza, the commanding officer of the Rabka resistance unit, who turned out to be a Gestapo agent. Dr Stefania and the other arrestees were taken to the Palace Hotel, a notorious Gestapo prison in Zakopane, where they were subjected to a brutal interrogation and then sent to Tarnów prison, from where she and others were deported to Auschwitz.

For a potted biography of Dr Janina Kościuszko, Stefania’s sister-in-law, see Kłodziński, S. “Dr Janina Kościuszkowa.” Kantor, M., trans. Medical Review – Auschwitz. March 23, 2019. Originally published in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1983: 162–168, on this website: https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/206350,dr-janina-kosciuszkowa.a - 102–104 degrees Fahrenheit.b

- Zofia Garlicka was born on June 19, 1874, in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, into the family of Feliks Wojtkiewicz and his wife Teofila née Bogórska, Poles deported for taking part in the anti-Russian Uprising of January 1863. On graduating from Nizhny Novgorod high school in 1895, Zofia left for Geneva, where she went up to the University of Geneva to read Medicine. In 1898, she moved to Zurich, where she graduated in 1899. As a student, she was involved in the activities of Polish students in Switzerland, and for a year she was active in the Zurich section of the International Union of Polish Socialists. She returned to Russia in 1900 and in the same year married Stanisław Garlicki, a chemical engineer she had met in Zurich. In October 1901, Zofia Garlicka took a specialist course in gynaecology and obstetrics at Prof. Henryk. Jordan's Clinic in Kraków. In 1903, she was employed in the factory hospital in the Raków district of Częstochowa and had a private surgery in Zawiercie. Stanisław Garlicki was a member of the Polish Socialist Party and was arrested in 1905 by the Russian authorities for his political involvement. He was amnestied four months later, and in 1906 withdrew from politics. He went abroad to study philosophy, history, natural sciences, and especially mathematics in Berlin, Zurich, and Paris. This was possible thanks to financial support from his wife, who moved from Częstochowa to Łódź in 1907 and took a doctor’s appointment in Scheibler’s textile factory. She was concerned about the huge infant mortality rate in the families of factory workers, which prompted her to systematically collect statistical material for a study on the need for maternity and baby care for working women. Dr Garlicka was also a member of the local Medical Society and the Drop of Milk institution, which provided baby supplements for nursing mothers. She organised a maternity home for a charity society, taught in a college for midwives, was head of a Russian hospital and ran a private medical practice. In 1918, she moved to Warsaw. Initially, Dr Garlicka was head of the gynaecological hospital run by the local branch of the Polish health insurance fund Kasa Chorych, and in 1930 became head of the gynsecology and obstetrics department at Ujazdowski Hospital. During the Second World War under German occupation, Dr Garlicka worked in a medical clinic at No. 13, ulica Lwowska, of which she was a co-owner, and also ran a private practice. She joined the Home Army (the largest Polish resistance movement), and was assigned to a group called Dorsze which cared for British soldiers who had escaped from German POW camps. Her apartment was a hideout for cichociemni Polish special operations paratroopers dropped in occupied Poland, and fugitives from German camps. She sheltered her Jewish friend, Dr Natalia Zylberblast-Zand. Arrested on 11 August 1941, she was sent to Auschwitz, where she was registered as No. 22521. She worked in the potato room. She died of typhus in Birkenau, probably on November 13, 1942, a few days after the death of her daughter, who was with her in the camp.a

- Janina Węgierska was born on October 13, 1912 in Pabianice.

As a child she was a girl scout, and later also an instructor in the rank of assistant scoutmistress. She participated in all the Polish scout rallies, as well as in the Slavic Rally in Prague. In the summer of 1939, she was an instructor in the Polish service camps, whose task was to train girl scouts for service in the event of war. In the same year, she graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at Poznań University. From September 1939 to April 1942, i.e., until her arrest, she worked in the military hospital in Włochy near Warsaw, as well as in a health center which she organized, and in hospitals in Warsaw. In 1940, she joined the Union of Armed Struggle (ZWZ, an early Polish resistance organization) and worked with her brother Kazimierz, a scoutmaster in the rank of lieutenant.

Dr Węgierska was arrested on April 23, 1942, while on night duty at the Infant Jesus Hospital. She was charged with plotting against the German occupying authorities. For six weeks she was imprisoned in the Gestapo headquarters on Aleja Szucha, then in the Pawiak prison, from where she and her sister Antonina were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 25, 1942. She was registered as No. 18296. When the camp was evacuated, she decided to stay with the seriously ill prisoners, taking care of them and making arrangements for their return home. In late July 1945, she returned to Poland and worked in the general and industrial health services until 1973. For 20 years she was the manager of the Sanitary and Epidemiological Station in the Bałuty district of Łódź. She made an active contribution to public affairs and worked for the Polish Red Cross. She lived in Zgierz.a - Władysława Jasińska (1895–1967). Deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on September 24, 1943, and registered as No. 63332. Sent to Bergen-Belsen in September 1944. For a potted biography of Dr Jasińska, see Kłodziński, S. “Dr Władysława Jasińska.” Kantor, M., trans. Medical Review – Auschwitz. September 7, 2020. Originally published under the same title in Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1969: 199–201, on this website: https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/243045,wladyslawa-jasinska.a

- Bolesław Zbozień (1909–1999; his name is misspelled in the original Polish article), a surgeon, arrived in Auschwitz on November 12, 1941 and registered as No. 22557. He was released from the camp on 6 April 1943. In the camp he was a member of the underground resistance movement in the men’s hospital. See https://polska1926.pl/files/2691/files/szpital-obozowy-dla-kobiet-w-kl-auschwitz-birkenau-1942-1945.pdf.c

- The official German term for “extermination camp” or “death camp.”b

- Zdenka Nedvědová-Nejedlá (1908–1998) was a Czech doctor, communist, and feminist, a member of the Czechoslovak anti-Nazi resistance movement, and subsequently a political prisoner and member of the prisoner doctors' medical staff in Terezín, Auschwitz, and Ravensbrück concentration camps. https://cs.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zdenka_Nedv%C4%9Bdov%C3%A1-Nejedl%C3%A1.a

- Katarzyna Łaniewska (1899–1976). Arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau on October 3, 1943 and registered as No. 64200. In 1944, she was moved to the Zigeunerlager (Roma camp). For a potted biography of Dr Łaniewska, see Kłodziński, S. “Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska.” Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, T., trans. Medical Review – Auschwitz. September 17, 2020. Originally published as “Dr Katarzyna Łaniewska.” Przegląd Lekarski – Oświęcim. 1978: 200–205, on this website:https://www.mp.pl/auschwitz/journal/english/246182,dr-katarzyna-laniewska.a

a—notes by Maria Ciesielska, Expert Consultant for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; b—notes by Teresa Bałuk-Ulewiczowa, Head Translator for the Medical Review Auschwitz project; c—Translator’s notes.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

A public task financed by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of Public Diplomacy 2022 (Dyplomacja Publiczna 2022) competition.

The contents of this site reflect the views held by the authors and do not constitute the official position of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.